Research on Evolution of Relevant Defects in Heavily Mg-Doped GaN by H Ion Implantation Followed by Thermal Annealing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

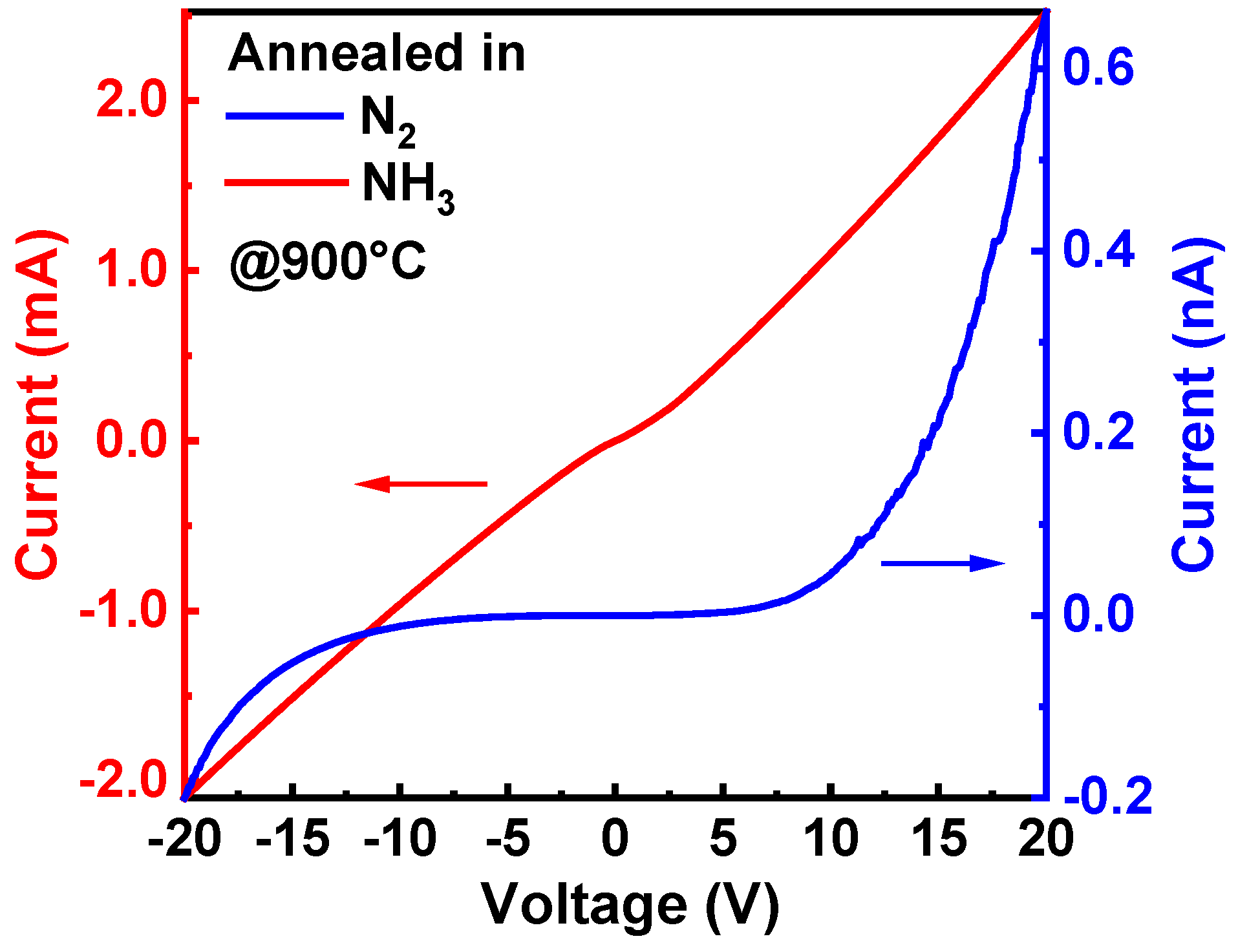

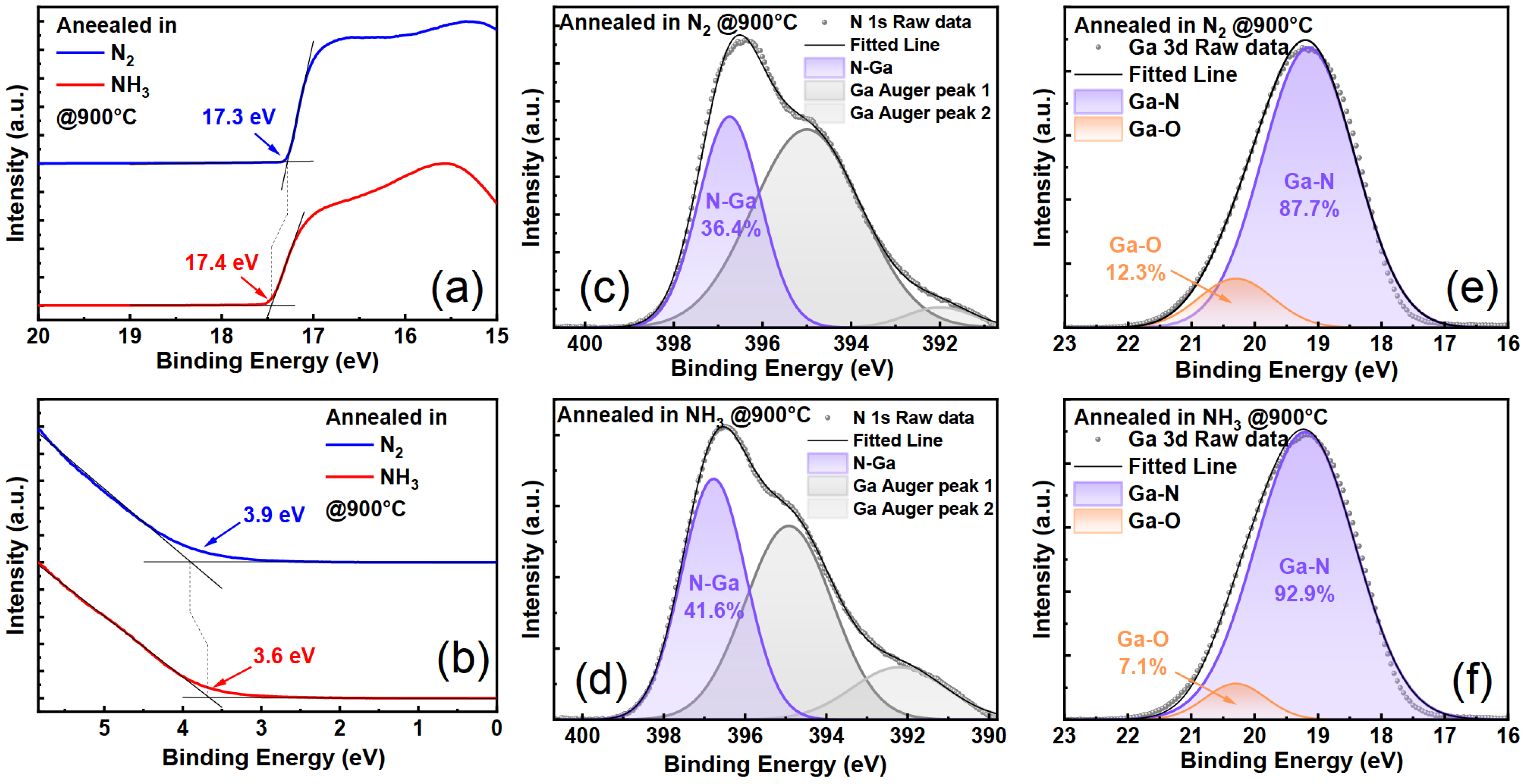

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Redistribution of H Ions

3.2. Behavior of Relevant Defects

3.2.1. H-Related Defects and Yellow Luminescence

3.2.2. Nitrogen Vacancies and Blue Luminescence

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moustakas, T.D.; Paiella, R. Optoelectronic Device Physics and Technology of Nitride Semiconductors from the UV to the Terahertz. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2017, 80, 106501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Nobel Prize in Physics. 2014. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2014/summary/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Kneissl, M.; Seong, T.-Y.; Han, J.; Amano, H. The Emergence and Prospects of Deep-Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diode Technologies. Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Iucolano, F.; Roccaforte, F. Review of Technology for Normally-off HEMTs with p-GaN Gate. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2018, 78, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Iwasa, N.; Senoh, M.; Mukai, T. Hole Compensation Mechanism of P-Type GaN Films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 31, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Mukai, T.; Senoh, M.; Iwasa, N. Thermal Annealing Effects on P-Type Mg-Doped GaN Films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 31, L139–L142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S. Nobel Lecture: Background Story of the Invention of Efficient Blue InGaN Light Emitting Diodes. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, A.; de Santi, C.; Carraro, C.; Sgarbossa, F.; Buffolo, M.; Diehle, P.; Gierth, S.; Altmann, F.; Hahn, H.; Fahle, D.; et al. Laser-Induced Activation of Mg-Doped GaN: Quantitative Characterization and Analysis. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 185104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, H.; Narita, T.; Omori, M.; Yamada, S.; Koura, A.; Iwinska, M.; Kataoka, K.; Horita, M.; Ikarashi, N.; Bockowski, M.; et al. Redistribution of Mg and H Atoms in Mg-Implanted GaN through Ultra-High-Pressure Annealing. Appl. Phys. Express 2020, 13, 086501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obloh, H.; Bachem, K.H.; Kaufmann, U.; Kunzer, M.; Maier, M.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Schlotter, P. Self-Compensation in Mg Doped p-Type GaN Grown by MOCVD. J. Cryst. Growth 1998, 195, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.L.; Janotti, A.; Van de Walle, C.G. Effects of Hole Localization on Limiting p -Type Conductivity in Oxide and Nitride Semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greczynski, G.; Hultman, L. A Step-by-Step Guide to Perform X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 011101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.G. The Pearson IV Distribution and Its Application to Ion Implanted Depth Profiles. Radiat. Eff. 1980, 46, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsch, A.G.; Oliver, D.N. Implantation through a Window with Medium to High Energy Ions. Microelectron. J. 1983, 14, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, R.; Jensen, K.F. Temperature Programmed Desorption Investigations of Hydrogen and Ammonia Reactions on GaN. Surf. Sci. 1997, 381, L581–L588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.-T.; Kim, D.-J.; Park, J.-S.; Oh, J.-T.; Lee, J.-M.; Park, S.-J. Recovery of Dry-Etch-Induced Surface Damage on Mg-Doped GaN by NH3 Ambient Thermal Annealing. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2004, 22, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeb, A.; Grieshaber, W.; Stocker, D.; Schubert, E.F.; Karlicek, R.F. Microcavity Effects in GaN Epitaxial Films and in Ag/GaN/Sapphire Structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 70, 2790–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hums, C.; Finger, T.; Hempel, T.; Christen, J.; Dadgar, A.; Hoffmann, A.; Krost, A. Fabry-Perot Effects in InGaN/GaN Heterostructures on Si-Substrate. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 033113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Gupta, M.; Waghmare, U.V.; Shivaprasad, S.M. Origin of Blue Luminescence in Mg-Doped Ga N. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2019, 11, 014027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucheyev, S.O.; Toth, M.; Phillips, M.R.; Williams, J.S.; Jagadish, C.; Li, G. Chemical Origin of the Yellow Luminescence in GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 91, 5867–5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.L.; Janotti, A.; Van De Walle, C.G. Carbon Impurities and the Yellow Luminescence in GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 152108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, C.B.; Chua, S.J.; Lim, H.F.; Chi, D.Z.; Tripathy, S.; Liu, W. Assignment of Deep Levels Causing Yellow Luminescence in GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Janotti, A.; Scheffler, M.; Van De Walle, C.G. Role of Nitrogen Vacancies in the Luminescence of Mg-Doped GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 142110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshchikov, M.A. On the Origin of the Yellow Luminescence Band in GaN. Phys. Status Solidi (B) 2023, 260, 2200488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Kuech, T.F. Hydrogen Induced Yellow Luminescence in GaN Grown by Halide Vapor Phase Epitaxy. J. Electron. Mater. 1998, 27, L35–L39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshchikov, M.A.; Morkoç, H. Luminescence Properties of Defects in GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 061301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernecki, R.; Grzanka, E.; Jakiela, R.; Grzanka, S.; Skierbiszewski, C.; Turski, H.; Perlin, P.; Suski, T.; Donimirski, K.; Leszczynski, M. Hydrogen Diffusion in GaN:Mg and GaN:Si. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 747, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wampler, W.R.; Myers, S.M.; Wright, A.F.; Barbour, J.C.; Seager, C.H.; Han, J. Lattice Location of Hydrogen in Mg Doped GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 90, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.W.; Rana, M.A.; Chua, S.J.; Osipowicz, T.; Pan, J.S. Surface Analysis of GaN Decomposition. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2002, 17, 1223–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bchetnia, A.; Kemis, I.; Touré, A.; Fathallah, W.; Boufaden, T.; Jani, B.E. GaN Thermal Decomposition in N2 AP-MOCVD Environment. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2008, 23, 125025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleske, D.D.; Wickenden, A.E.; Henry, R.L.; Culbertson, J.C.; Twigg, M.E. GaN Decomposition in H2 and N2 at MOVPE Temperatures and Pressures. J. Cryst. Growth 2001, 223, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodzicki, M.; Mazur, P.; Ciszewski, A. Changes of Electronic Properties of P-GaN(0 0 0 1) Surface after Low-Energy N+-Ion Bombardment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 440, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahat, M.R.; Talik, N.A.; Abd Rahman, M.N.; Anuar, M.A.; Allif, K.; Azman, A.; Nakajima, H.; Shuhaimi, A.; Abd Majid, W.H. Electronic Surface, Optical and Electrical Properties of p-GaN Activated via in-Situ MOCVD and Ex-Situ Thermal Annealing in InGaN/GaN LED. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 106, 104757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Chu, Y.-L. Effect of Reactive Ion Etching-Induced Defects on the Surface Band Bending of Heavily Mg-Doped p-Type GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 104904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Hallén, A.; Nazir, A. Ion Implantation Induced Nitrogen Defects in GaN. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2015, 48, 455107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, G.; Roe, M.J.; Harrison, I.; Kappers, M.; Humphreys, C.J.; Brown, P.D. Effects of KOH Etching on the Properties of Ga-Polar n-GaN Surfaces. Philos. Mag. 2006, 86, 2315–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Kong, W.; Li, J.; Collar, K.; Kim, T.-H.; Losurdo, M.; Brown, A.S. Characterization of MBE-Grown InAlN/GaN Heterostructure Valence Band Offsets with Varying in Composition. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 035211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Z.; Yan, D.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Wei, X. Research on Evolution of Relevant Defects in Heavily Mg-Doped GaN by H Ion Implantation Followed by Thermal Annealing. Materials 2024, 17, 2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112518

Jiang Z, Yan D, Zhang N, Wang J, Wei X. Research on Evolution of Relevant Defects in Heavily Mg-Doped GaN by H Ion Implantation Followed by Thermal Annealing. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112518

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Zonglin, Dan Yan, Ning Zhang, Junxi Wang, and Xuecheng Wei. 2024. "Research on Evolution of Relevant Defects in Heavily Mg-Doped GaN by H Ion Implantation Followed by Thermal Annealing" Materials 17, no. 11: 2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112518

APA StyleJiang, Z., Yan, D., Zhang, N., Wang, J., & Wei, X. (2024). Research on Evolution of Relevant Defects in Heavily Mg-Doped GaN by H Ion Implantation Followed by Thermal Annealing. Materials, 17(11), 2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112518