Volume Stability and Frost Resistance of High–Ductility Magnesium Phosphate Cementitious Concrete

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

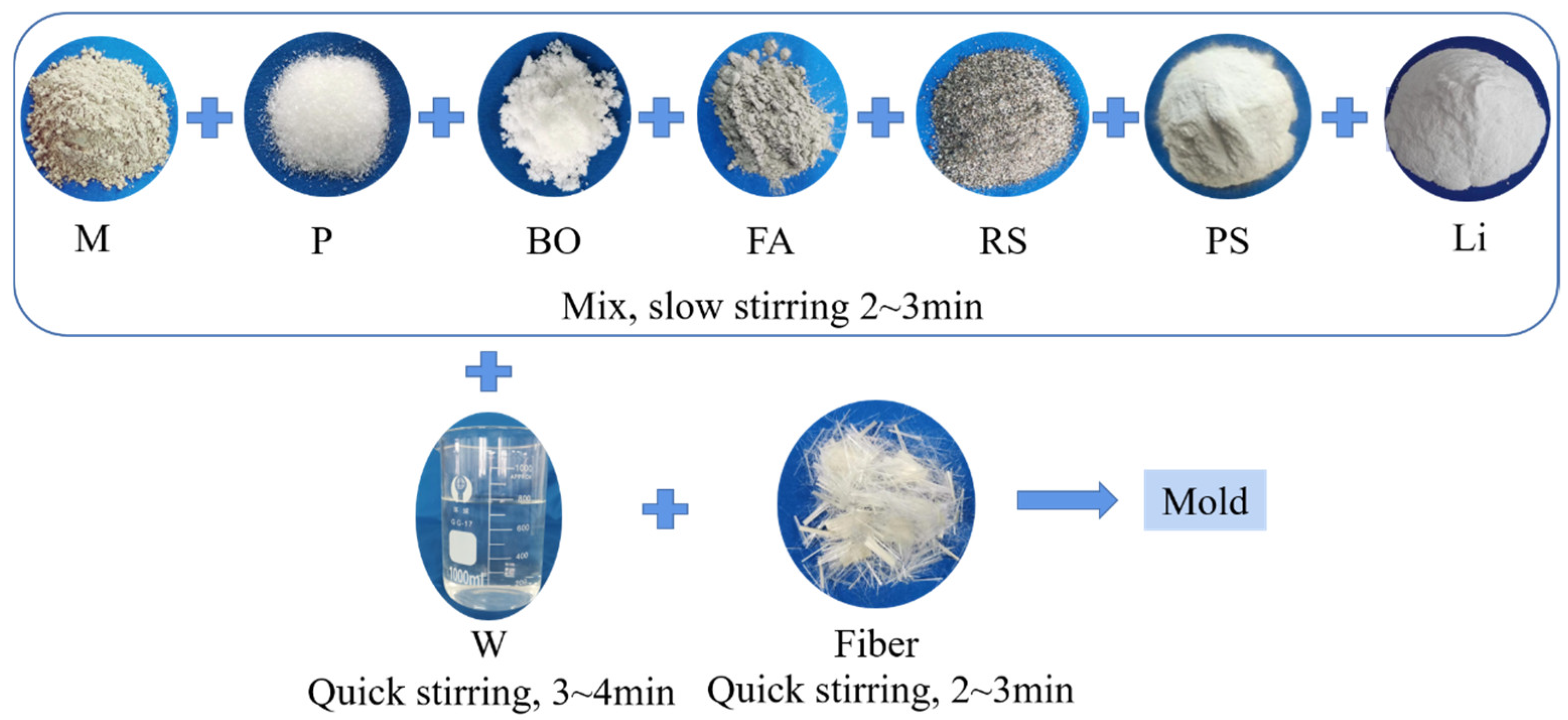

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Mix Proportion

2.3. Specimen Process

2.4. Test Methods

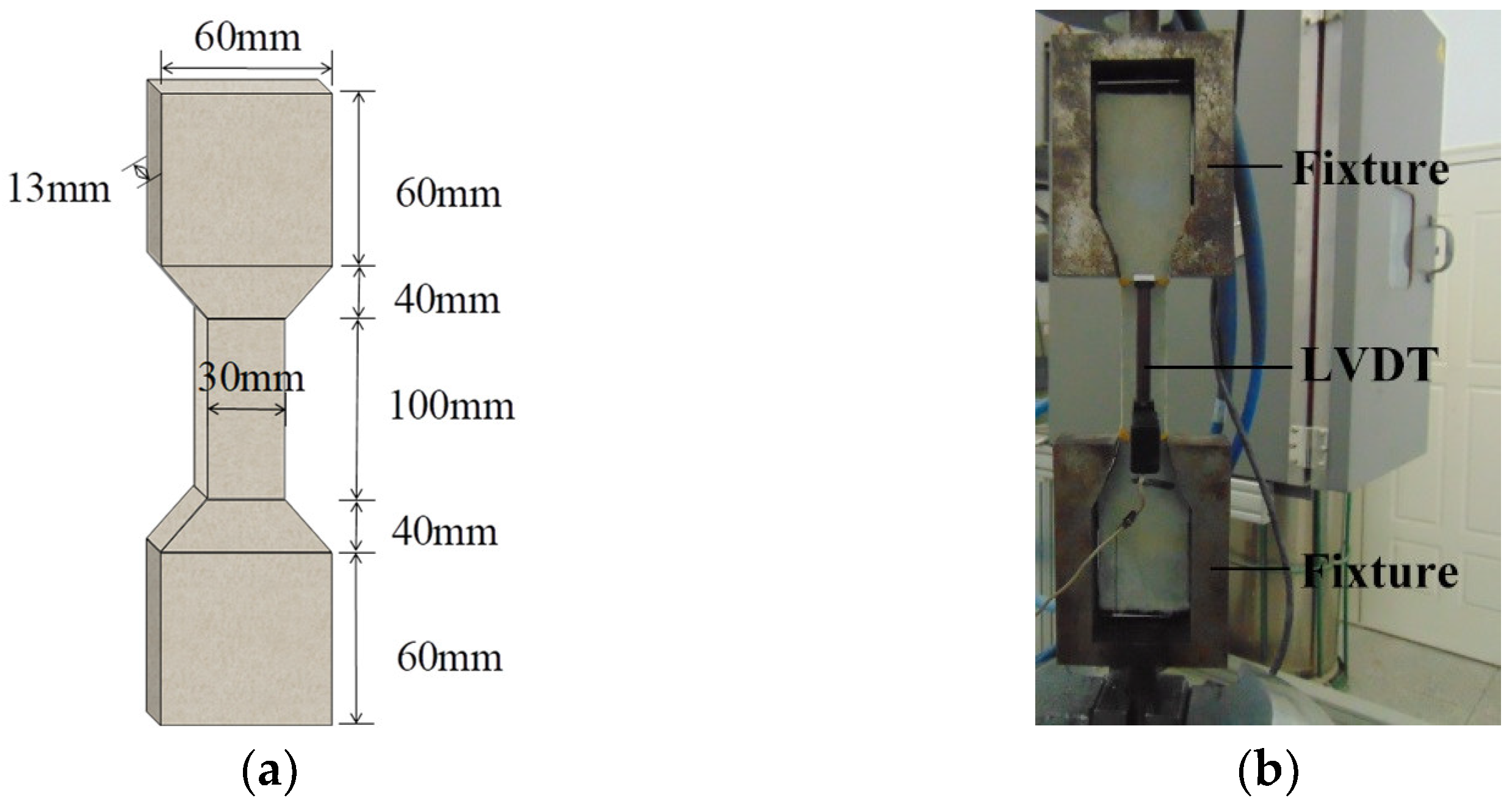

2.4.1. Mechanical Properties

2.4.2. Deformation Performance

2.4.3. Frost Resistance

2.4.4. Pore Structure

3. Results and Discussion

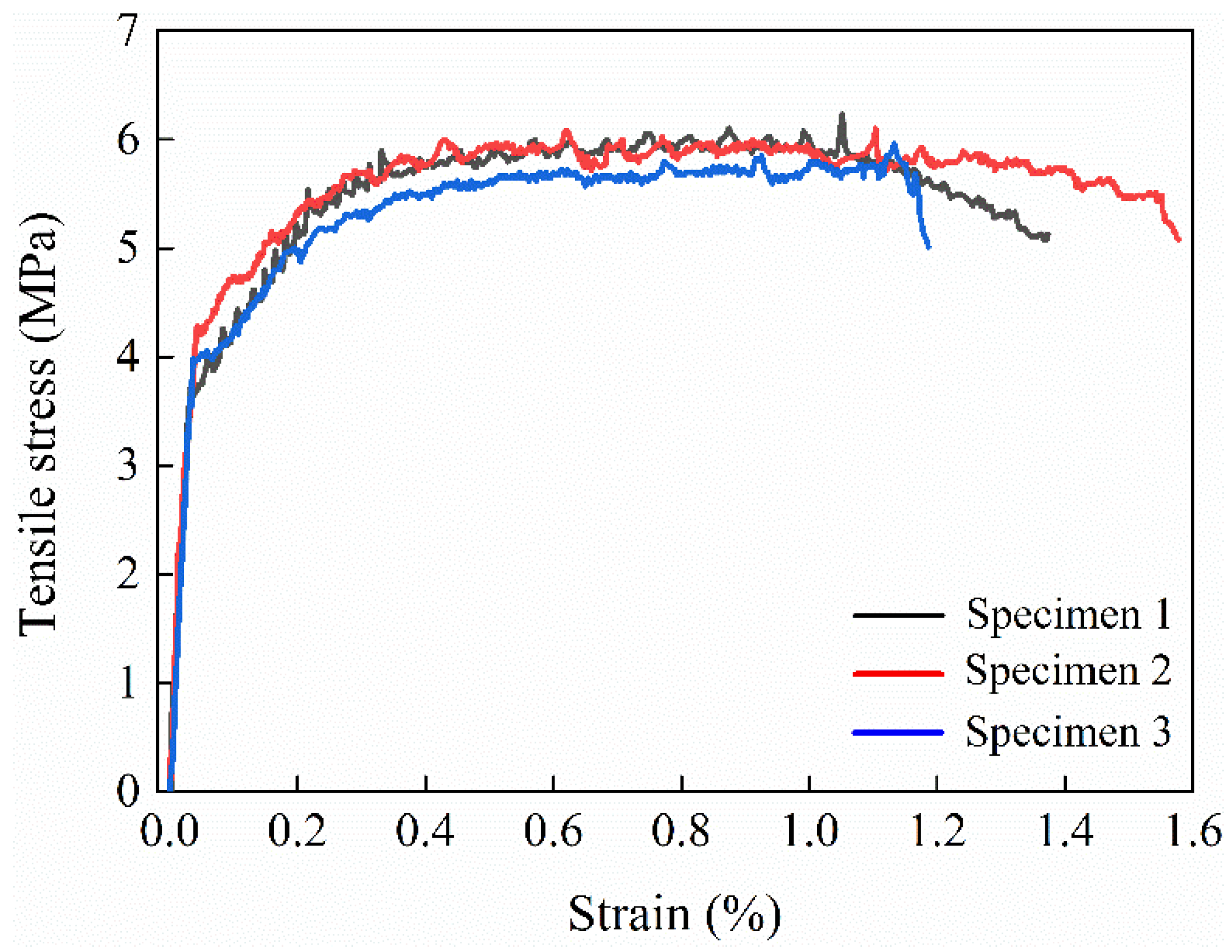

3.1. Mechanical Performance

3.2. Relationship between Age and Deformation in HD–MPCC

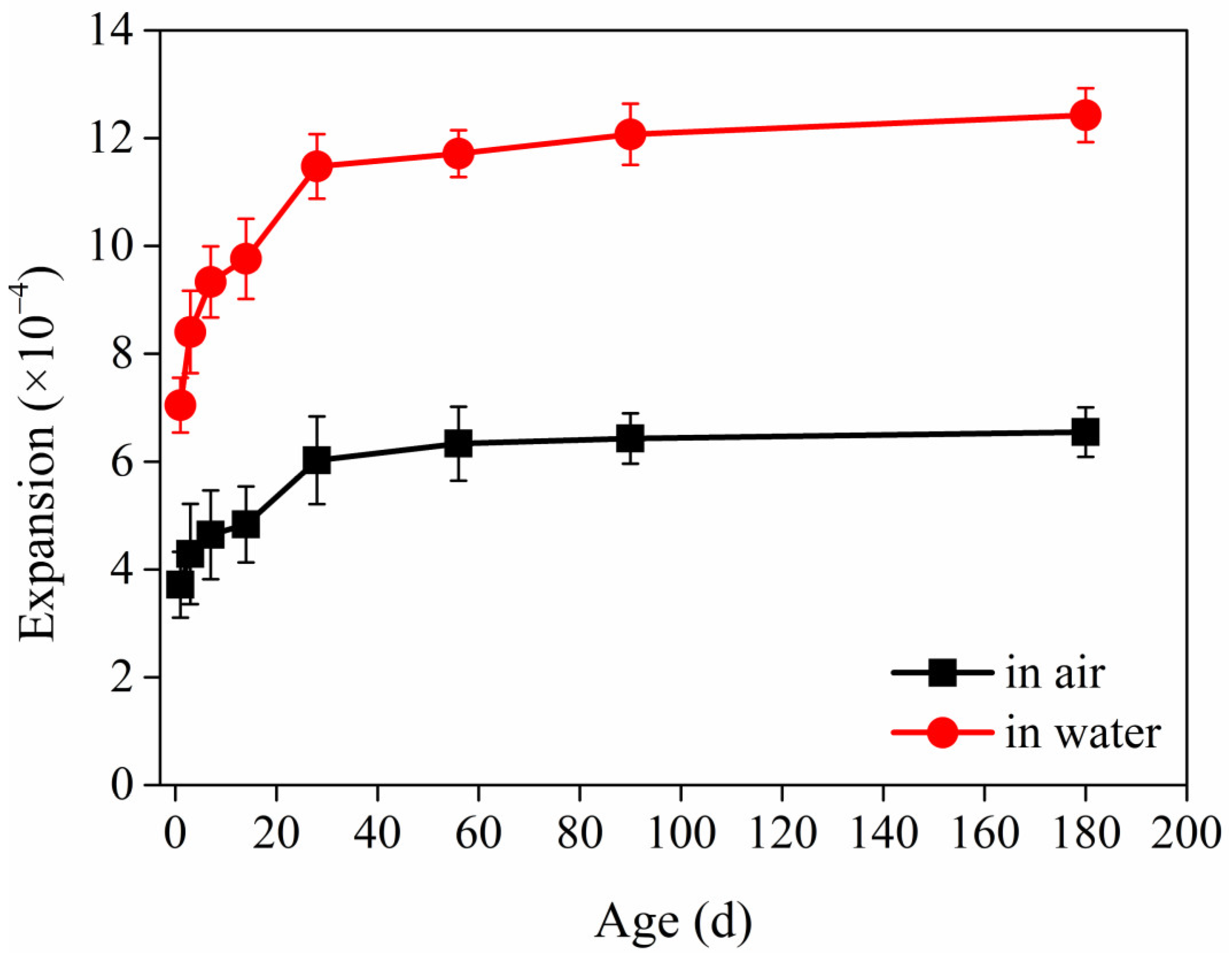

3.2.1. Deformation Performance

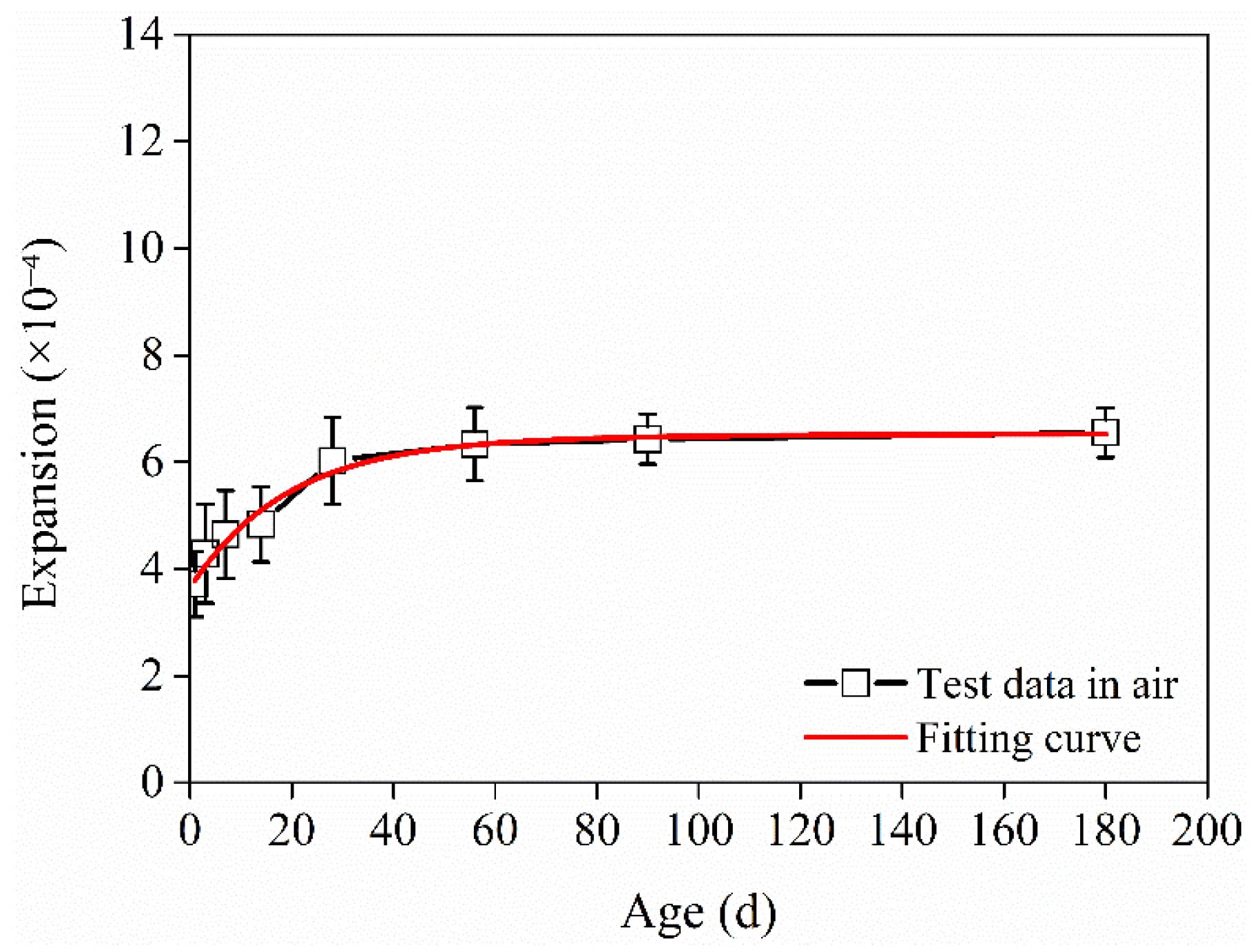

3.2.2. Relationship between Deformation and Time Cured in Air in HD–MPCC

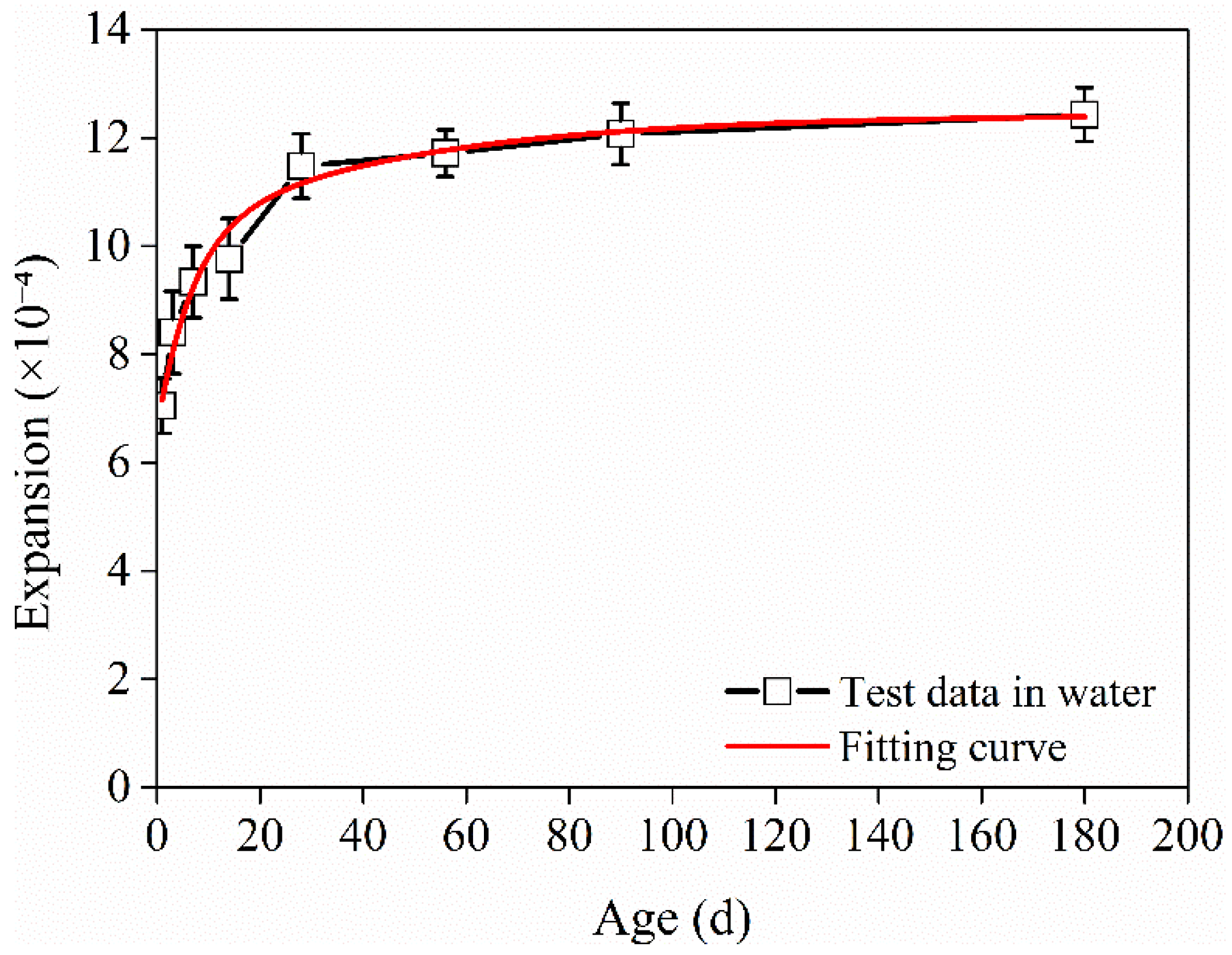

3.2.3. Relationship between Deformation and Time Cured in Water in HD–MPCC

3.3. Frost Resistance

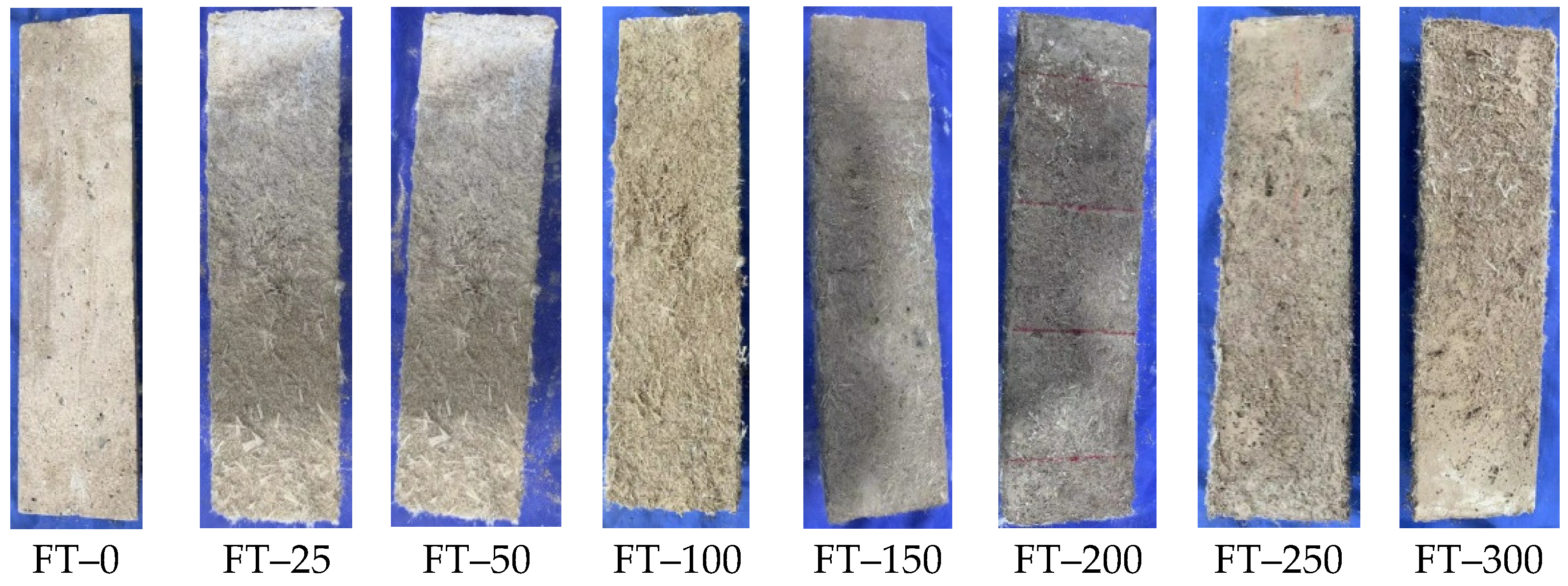

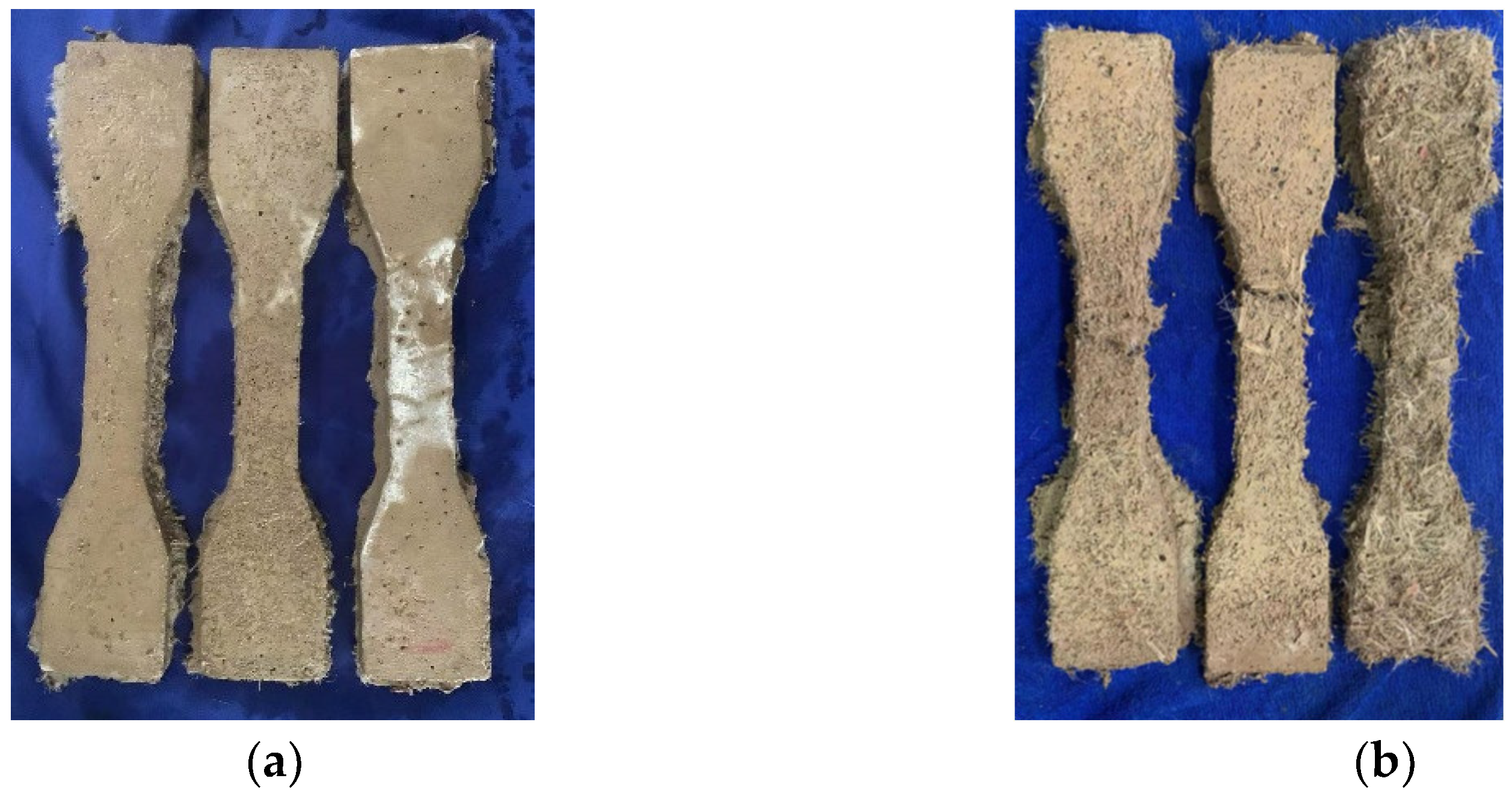

3.3.1. Appearance of Specimen

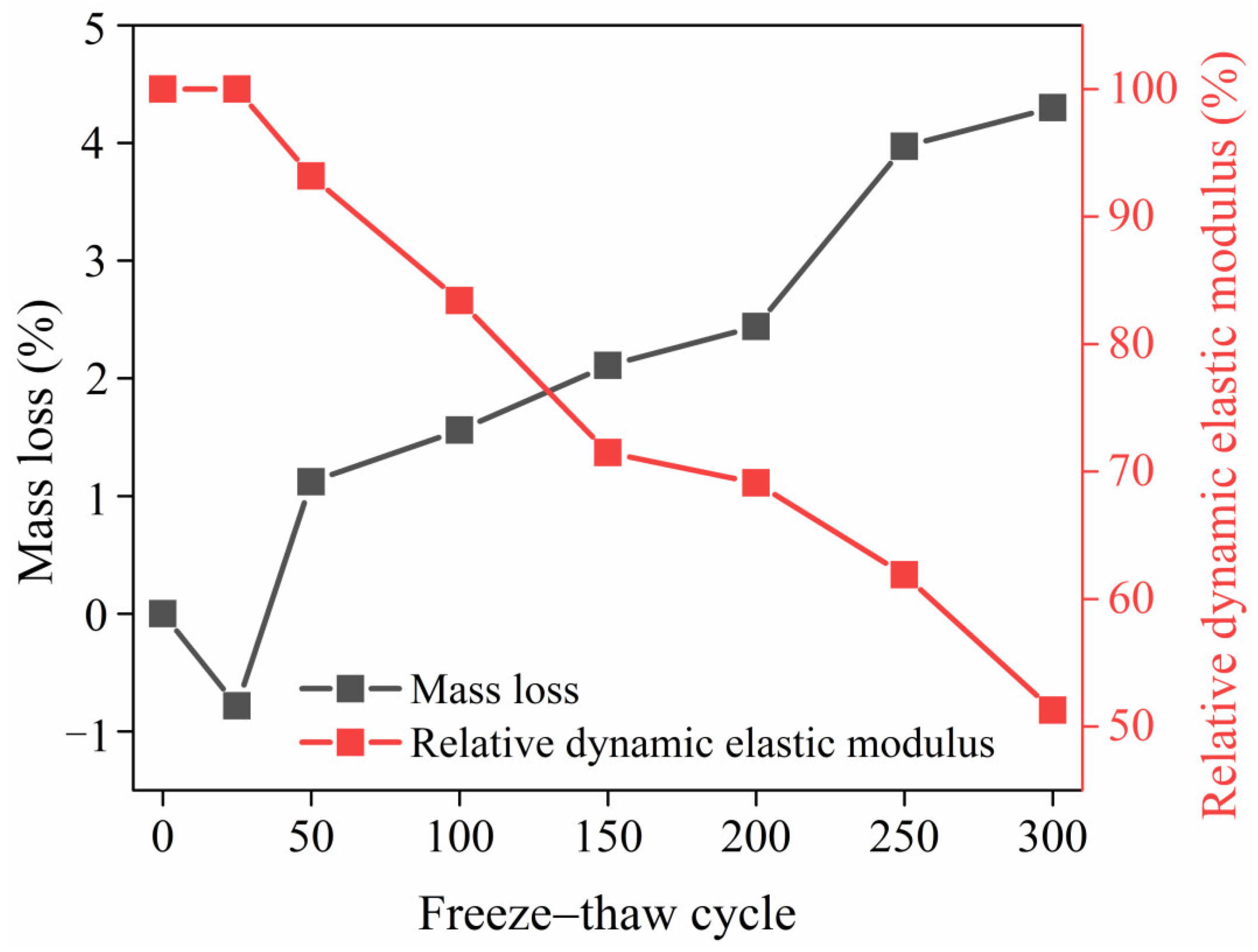

3.3.2. Mass Loss and Relative Dynamic Elastic Modulus

3.3.3. Tensile Property of HD–MPCC after Different Numbers of Freeze–Thaw Cycles

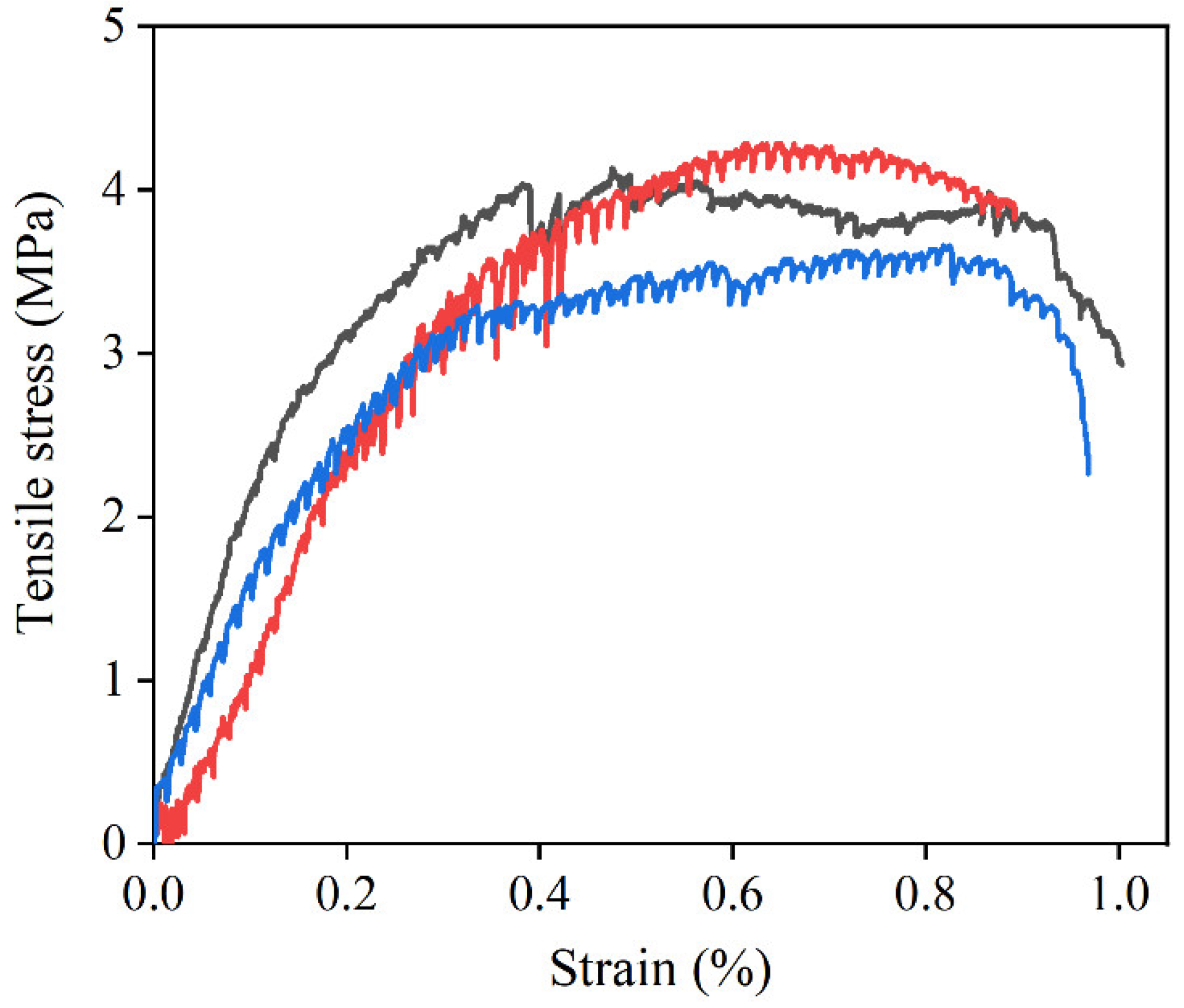

3.3.4. Flexural Property of HD–MPCC after Different Numbers of Freeze–Thaw Cycles

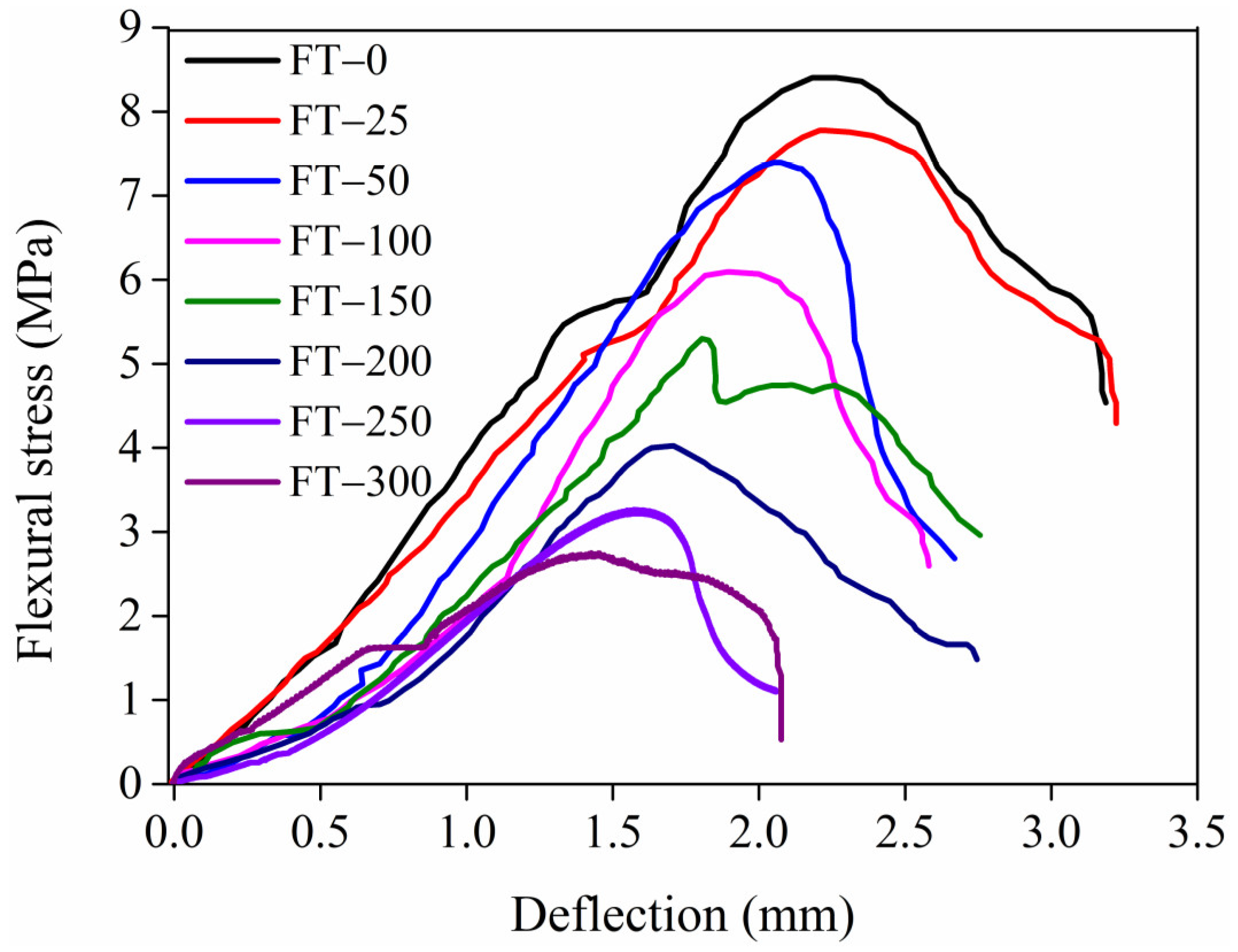

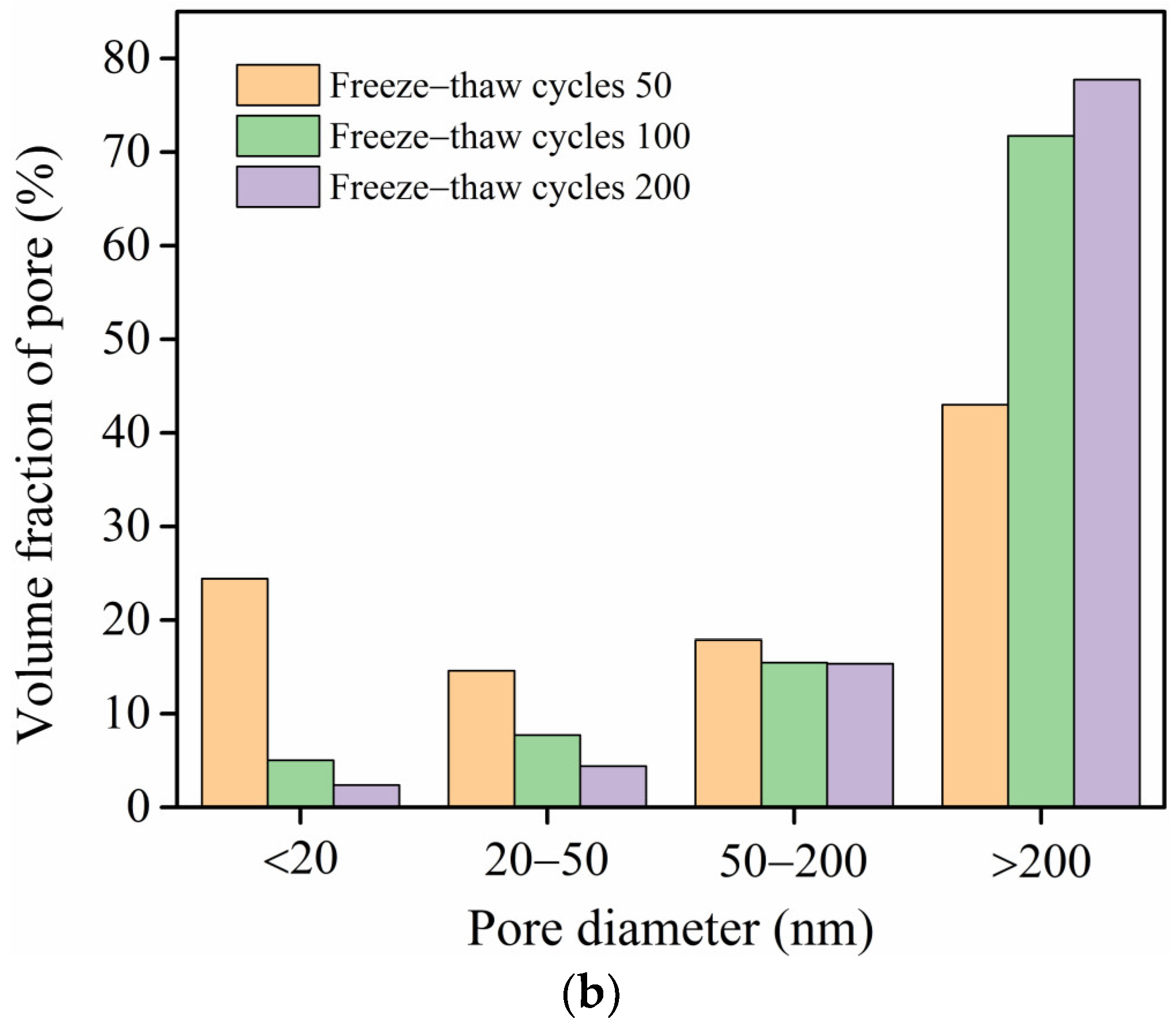

3.4. Pore Structure

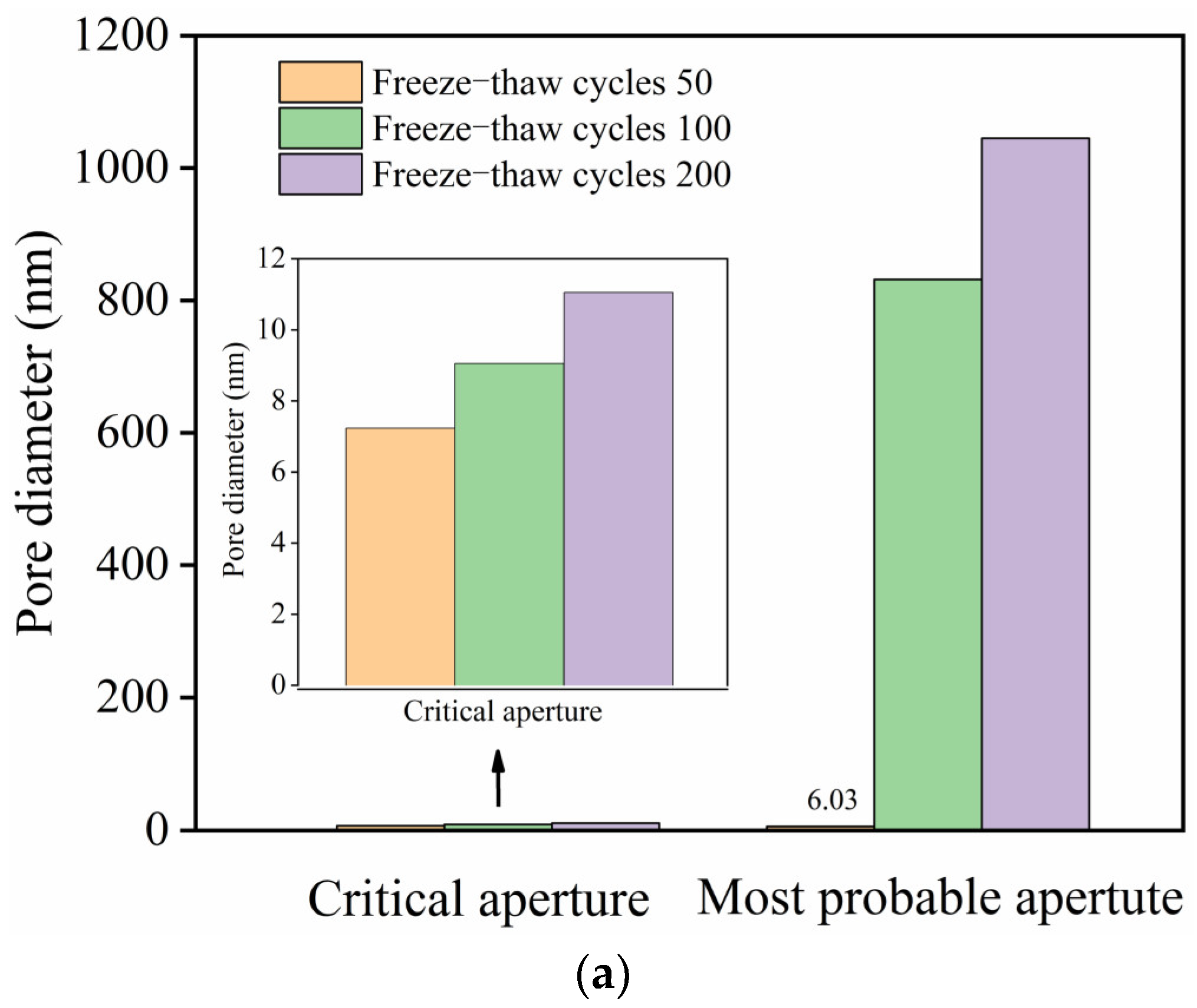

4. Conclusions

- The expansion deformation of the HD–MPCC is observed when cured in both air and water. Within a curing period of 28 days, the increasing trend of expansion deformation is obvious, while after 28 days, the increasing trend of expansion deformation slows down. When the curing age is consistent, the expansion deformation of the HD–MPCC cured in water is greater than that of the HD–MPCC in air, indicating the poorer volume stability of the HD–MPCC in water.

- With an increasing number of freeze–thaw cycles, the relative dynamic elastic modulus of the HD–MPC decreases, and the mass loss initially decreases then increases. The HD–MPCC specimens peel off from the surface to the inside, and the internal damage to the specimens becomes more severe with more freeze–thaw cycles.

- After 25 freeze–thaw cycles, both the ultimate tensile strength and ultimate tensile strain of the HD–MPCC decrease. Similarly, the flexural strength and peak deflection of the HD–MPCC reduce with the increase in freeze–thaw cycles.

- As the freeze–thaw cycles continue, the most probable aperture and critical aperture of the HD–MPCC pure paste show increasing trends, and the volume fractions of harmless pores and less harmful pores decrease, while the volume fraction of more harmful pores increases. This deterioration in pore structure results in decreased ultimate tensile strength, flexural strength, ultimate tensile strain, and flexural deflection.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Z.H.; Liu, S.J.; Wu, K.; Yu, L.; Pan, F. Research progress on fiber reinforced magnesium phosphate cement composites. Mater. Rep. 2023, 37, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Y. Research on Development and Application Technology of Fast Repair Material MPC for Cement Pavement. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou Jiaotong University, Lanzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Formosa, J.; Lacasta, A.M.; Navarro, A.; del Valle-Zermeno, R.; Niubo, M.; Rosell, J.R.; Chimenos, J.M. Magnesium phosphate cements formulated with a low-grade mgo by-product: Physico-mechanical and durability aspects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 91, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Li, X.; Jia, X.W.; Qian, J.S. Bond strength and interface characteristics between magnesium phosphate cement mortar and ordinary Portland cement concrete in a frigid environment. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2024, 25, 2318610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yan, C.W.; Liu, S.G.; Jing, L.; Yin, L.Q.; Wang, X.X. Toughness and strength of PVA-fibre reinforced magnesium phosphate cement (FRMPC) within 24 h. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 418, 135339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JC/T 2461-2018; Standard Test Method for the Mechanical Properties of Ductile Fiber Reinforced Cementitious Composites. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Curosu, L.; Liebscher, M.; Alsous, G.; Muja, E.; Li, H.Y.; Drechsler, A.; Frenzel, R.; Synytska, A.; Mechtcherine, V. Tailoring the crack-bridging behavior of strain-hardening cement-based composites (SHCC) by chemical surface modification of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) fibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.L.; Wu, P.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, X.; Chen, B.K.; Li, Q.H. A dynamic constitutive model of ultra high toughness cementitious composites. J. Zhe Jiang Univ.-Sci. 2020, 21, 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, L.F.; Xia, L.P. Investigation of the behaviour of flexible and ductile ECC link slab reinforced with FRP. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.K.; Zhang, M.; Ma, F.D.; Li, F.Y.; Sun, H.Z. Flexural strengthening of over-reinforced concrete beams with highly ductile fiber-reinforced concrete layer. Eng. Struct. 2021, 231, 111725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.P.; Wang, M.; Ding, C.; Chai, L.J. Effect of incorporating reclaimed asphalt pavement on macroscopic and microstructural properties of high ductility cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 119956. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, L.J.; Guo, L.P.; Chen, B.; Xu, Y.H. Interactive effects of freeze-thaw cycle and carbonation on tensile property of ecological high ductility cementitious composites for bridge deck link slab. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Liang, J.H.; Guo, A.F.; Lv, L.J.; Sun, Z.H.; Sheikh, M.N.; Liu, F.J. Development and design of ultra-high ductile magnesium phosphate cement-based composite using fly ash and silica fume. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 137, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Nie, S.; Guo, A.F.; Lv, L.J.; Yu, J.H. Evaluation on the performance of magnesium phosphate cement-based engineered cementitious composites (MPC-ECC) with blended fly ash/ silica fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, F.; Chau, C.K.; Li, Z.J. Property evaluation of magnesium phosphate cement mortar as patch repair material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.B.; Tang, X.S.; Huang, G.H.; Zhu, Y.R.; Ma, J.N. Performance testing on rapid repair materials of magnesium phosphate cement. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 2017, 37, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Chen, B. Properties of magnesium phosphate cement containing redispersible polymer powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 113, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, B. Factors that affect the properties of magnesium phosphate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.W.; Qian, C.; Chen, Q. Experimental investigation on the volume stability of magnesium phosphate cement with different types of mineral admixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 157, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.L.; Wang, B.; Han, Z.C.; Ji, R.J. Experimental study of magnesium ammonium phosphate cements modified by fly ash and metakaolin. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.B.; Wu, X.L. Factors influencing properties of phosphate cement-based binder for rapid repair of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.Y.; Xu, B.W.; Liu, J.; Pei, H.F.; Li, Z.J. Effects of water content, magnesia-to-phosphate molar ratio and age on pore structure, strength and permeability of magnesium potassium phosphate cement paste. Mater. Design 2014, 64, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.D. Study on the Stability of Magnesium Phosphate Cement Cured in Water and Its Influencing Factors. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.B.; Zhang, S.Q.; Wu, X.L. Deicer-scaling resistance of phosphate cement-based binder for rapid repair of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Nuliyanmu, X.F.K.T.; Chen, C.; Guo, J.; Bao, D.X. Study on frost resistance of rapid-hardening magnesium phosphate-ferro-aluminate composite cement. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2022, 44, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Q.; Wang, Y. Mechanical properties and frost resistance of magnesium phosphate cement concrete under negative temperature. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2018, 40, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.L.; Cao, Z.; Wei, C.; Shao, Y.; Wu, P.F.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Liu, X.M. Red mud-modified magnesium potassium phosphate cement used as rapid repair materials: Durability, bonding property, volume stability and environment performance optimization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 415, 135144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.Q.; Hou, Y.Y.; Mei, J.T.; Yang, J.M.; Gan, T. Influence of synthetic limestone sand on the frost resistance of magnesium potassium phosphate cement mortar. Materials 2022, 15, 6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.J.; Guo, L.P.; Chen, B.; Cao, Y.Z.; Xu, Y.H. Flexural behaviors of ecological high ductility cementitious composites subjected to interaction of freeze-thaw cycles and carbonation. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2019, 17, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Building Materials Federation. Magnesium Phosphate Repairing Mortar: JC/T 2537-2019; China Building Materials Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, L.J.; Yue, Z.H.; Guo, L.P.; Chen, B.; Wang, L.Y. Preparation and performance optimization design of high ductility magnesium phosphate cementitious rapid repair material. Acta Mater. Compos. Sinica. 2024, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCCC Highway Consultants Co., Ltd. General Specifications for Design of Highway Bridges and Culverts: JTG D60-2015; China Communications Press Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- JGJ/T70-2009; Standard for Test Method of Performance on Building Mortar. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- GB/T 50082-2009; Standard for Test Methods of Long-Term Performance and Durability of Ordinary Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Gao, Y.X.; Qin, J.H.; Li, Z.; Jia, X.W.; Qian, J.S. Creep deformation and its effect on mechanical properties and microstructure of magnesium phosphate cement concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Length (mm) | Mean Diameter (μm) | Density (kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Ultimate Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 39 | 1300 | 30 | ≥1250 | 5~8 |

| M | P | FA | BO | RS | PS | Li | W | PVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 570 | 190 | 190 | 171 | 950 | 10.45 | 28.5 | 171 | 26 |

| Freeze–Thaw Cycle | First–Cracking Strength (MPa) | First–Cracking Strain (%) | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Ultimate Tensile Strain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.41 ± 0.53 | 0.03 ± 0.007 | 6.10 ± 0.09 | 1.10 ± 0.50 |

| 25 | 3.16 ± 0.07 | 0.03 ± 0.001 | 3.94 ± 0.18 | 0.82 ± 0.07 |

| Freeze–Thaw Cycle | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Peak Deflection (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8.40 | 2.27 |

| 25 | 7.78 | 2.21 |

| 50 | 7.39 | 2.08 |

| 100 | 6.09 | 1.89 |

| 150 | 5.30 | 1.80 |

| 200 | 4.02 | 1.71 |

| 250 | 3.26 | 1.62 |

| 300 | 2.75 | 1.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chai, L.; Yue, Z.; Chen, Z.; Fan, G.; Wang, L. Volume Stability and Frost Resistance of High–Ductility Magnesium Phosphate Cementitious Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112522

Chai L, Yue Z, Chen Z, Fan G, Wang L. Volume Stability and Frost Resistance of High–Ductility Magnesium Phosphate Cementitious Concrete. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112522

Chicago/Turabian StyleChai, Lijuan, Zhonghua Yue, Zhichun Chen, Gaoyu Fan, and Liuye Wang. 2024. "Volume Stability and Frost Resistance of High–Ductility Magnesium Phosphate Cementitious Concrete" Materials 17, no. 11: 2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112522