Ultrasonic Non-Destructive Detection Method for Residual Stress in Rotary Forging Aluminum Alloy Plates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Theory of Longitudinal Critically Refracted Wave Detection

2.2. Principles of the LCR Wave Method for Detecting Residual Stress at Different Depths

3. Sample Preparation and Finite Element Modeling

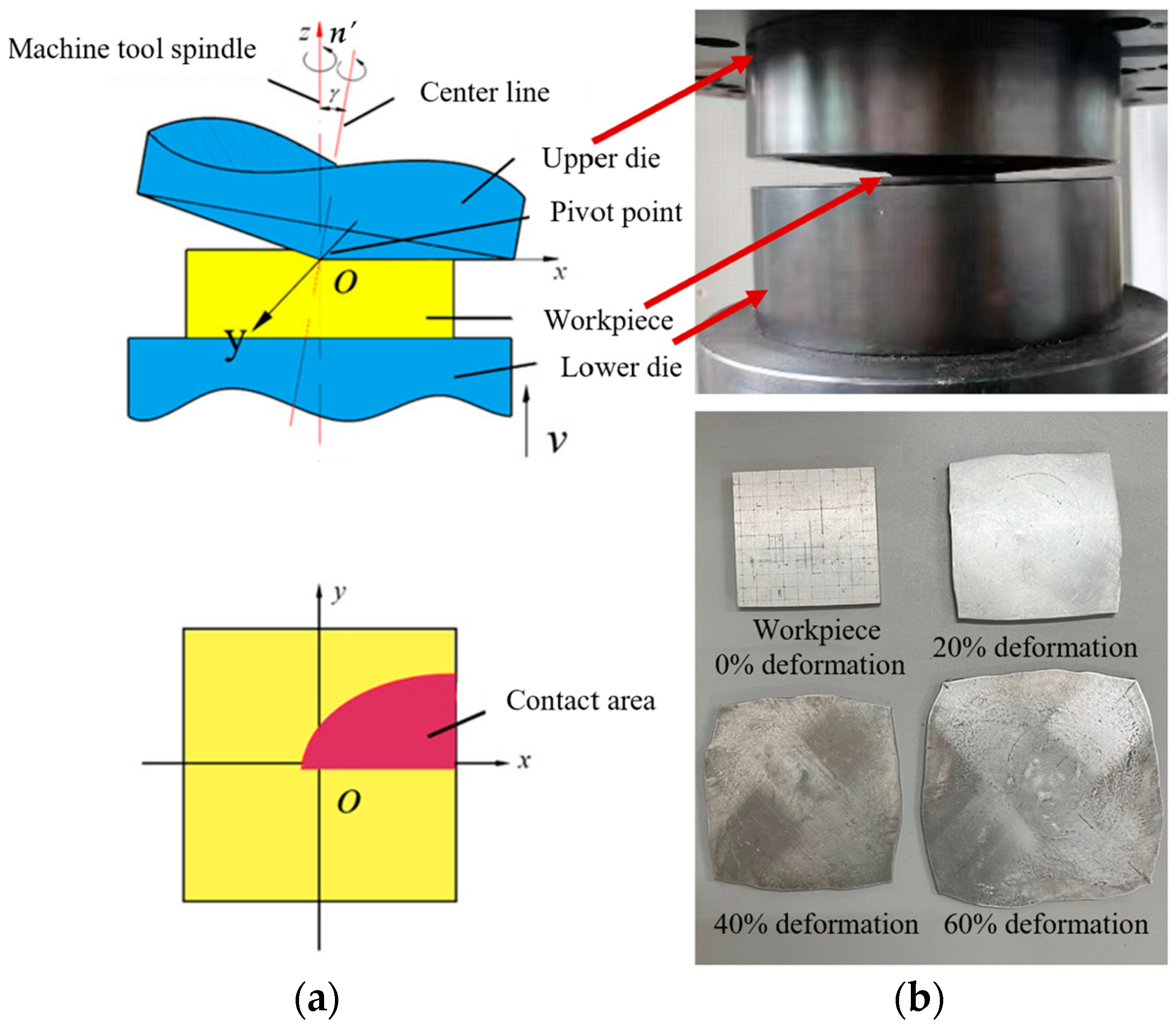

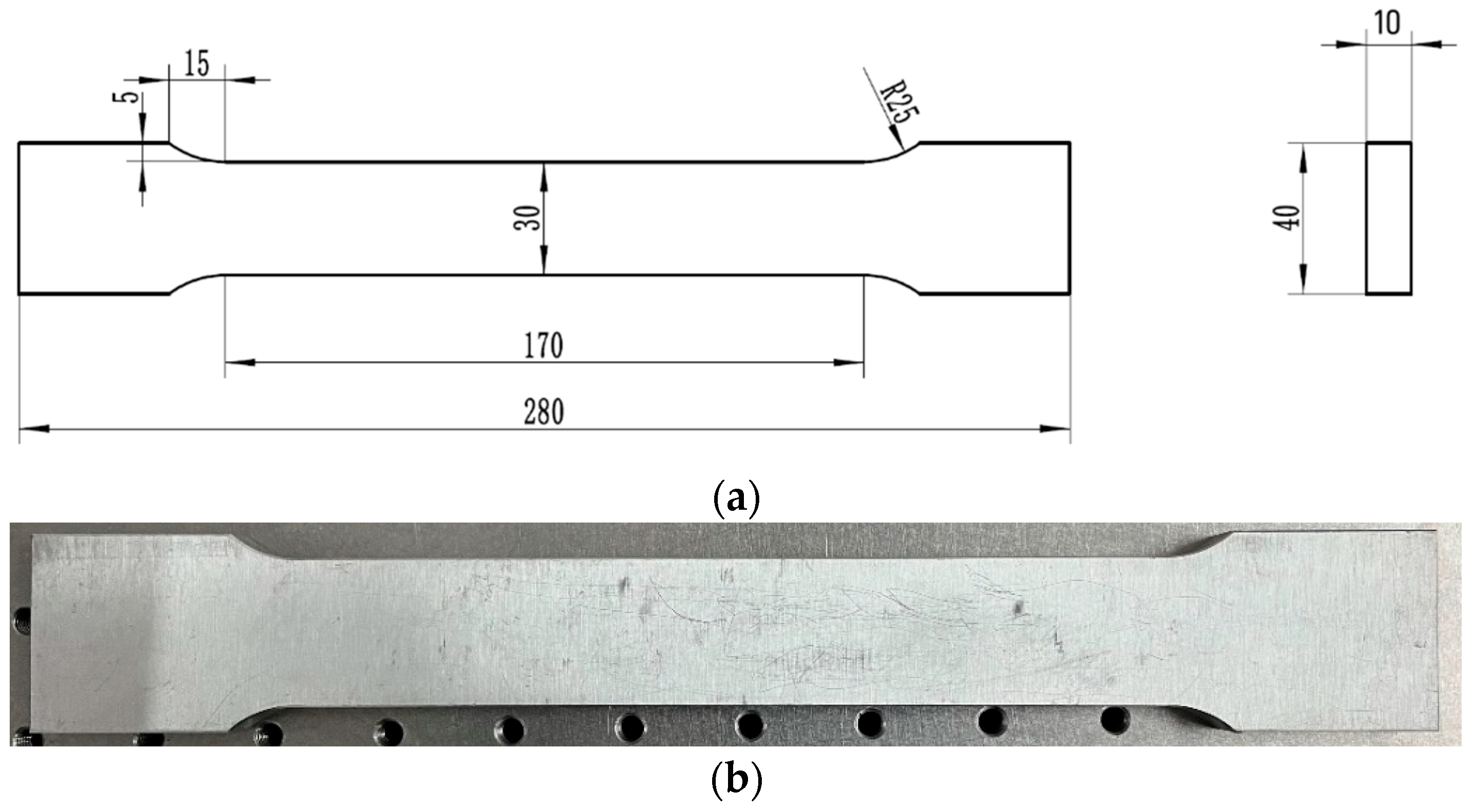

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.2. FE Model for Simulating Rotary Forging

4. Experimental Procedures

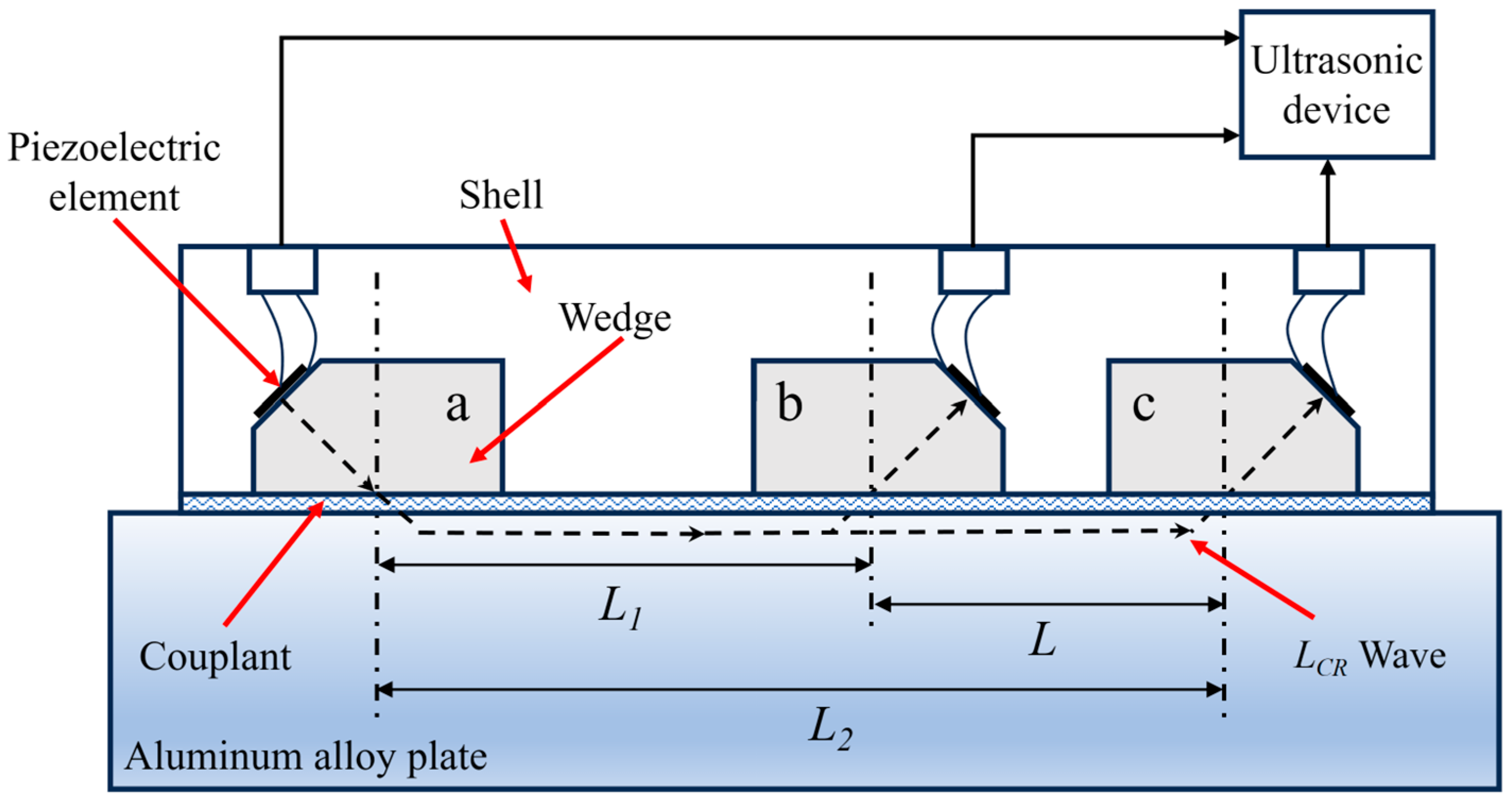

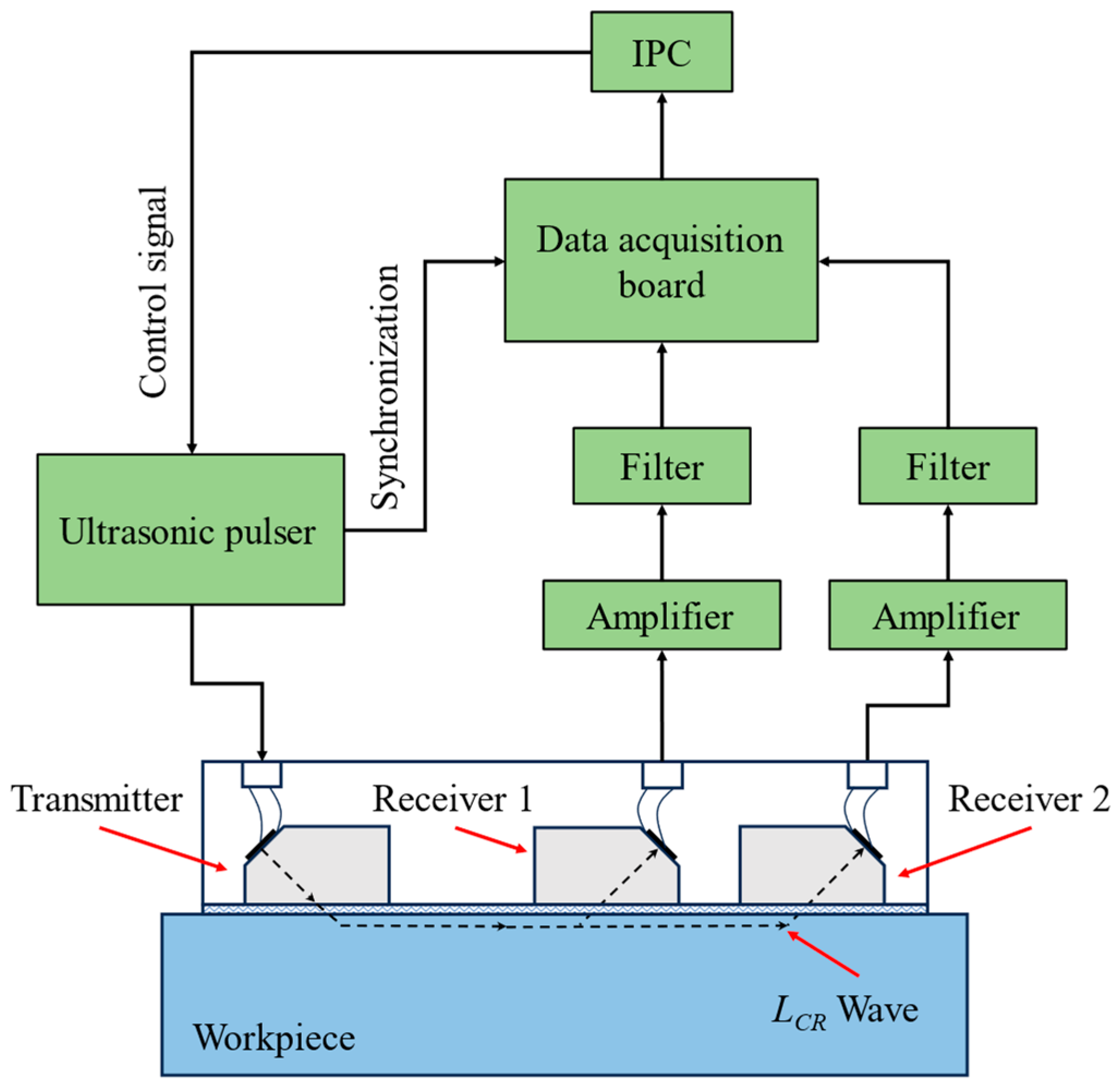

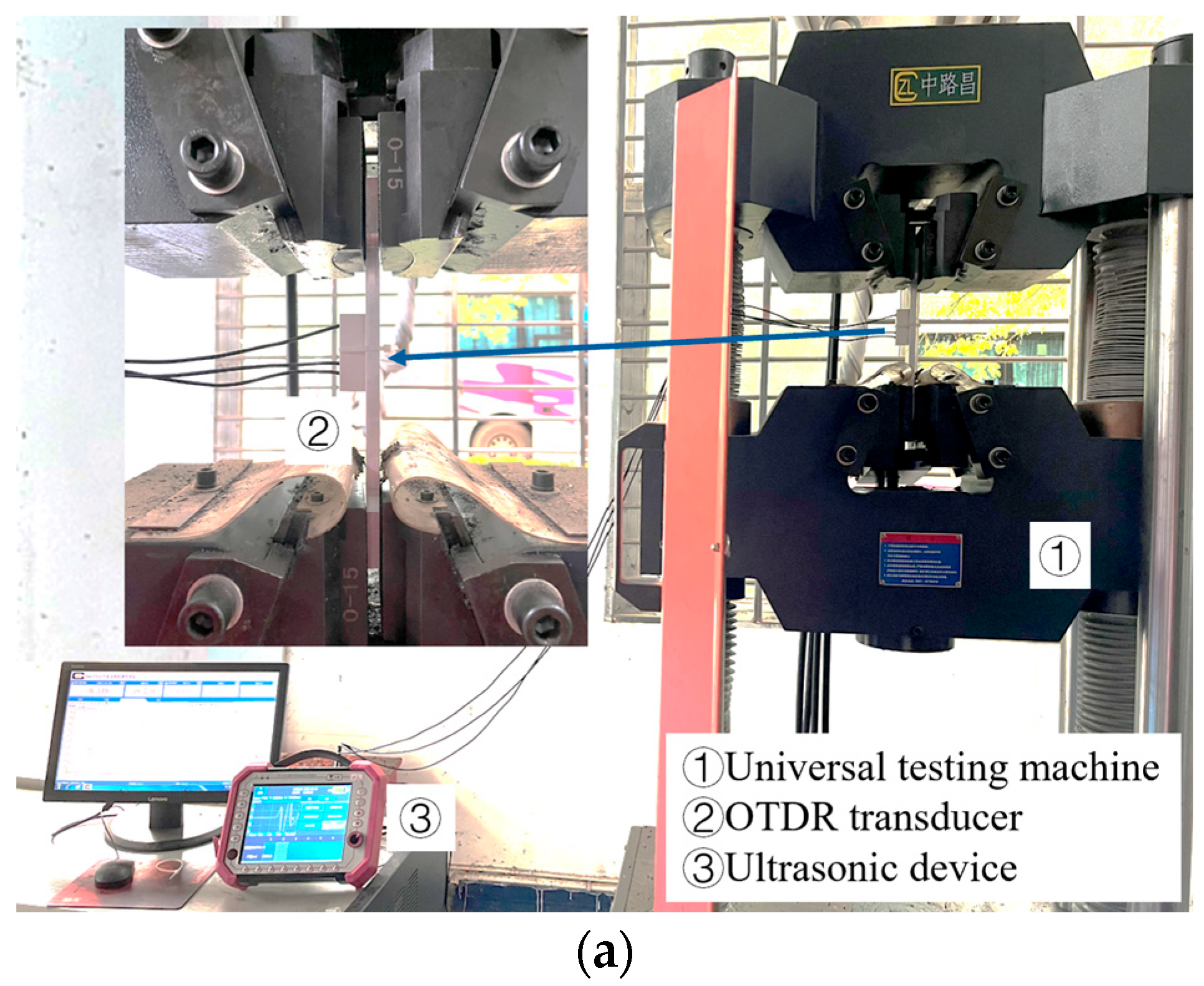

4.1. LCR Wave Residual Stress Ultrasonic Detecting System

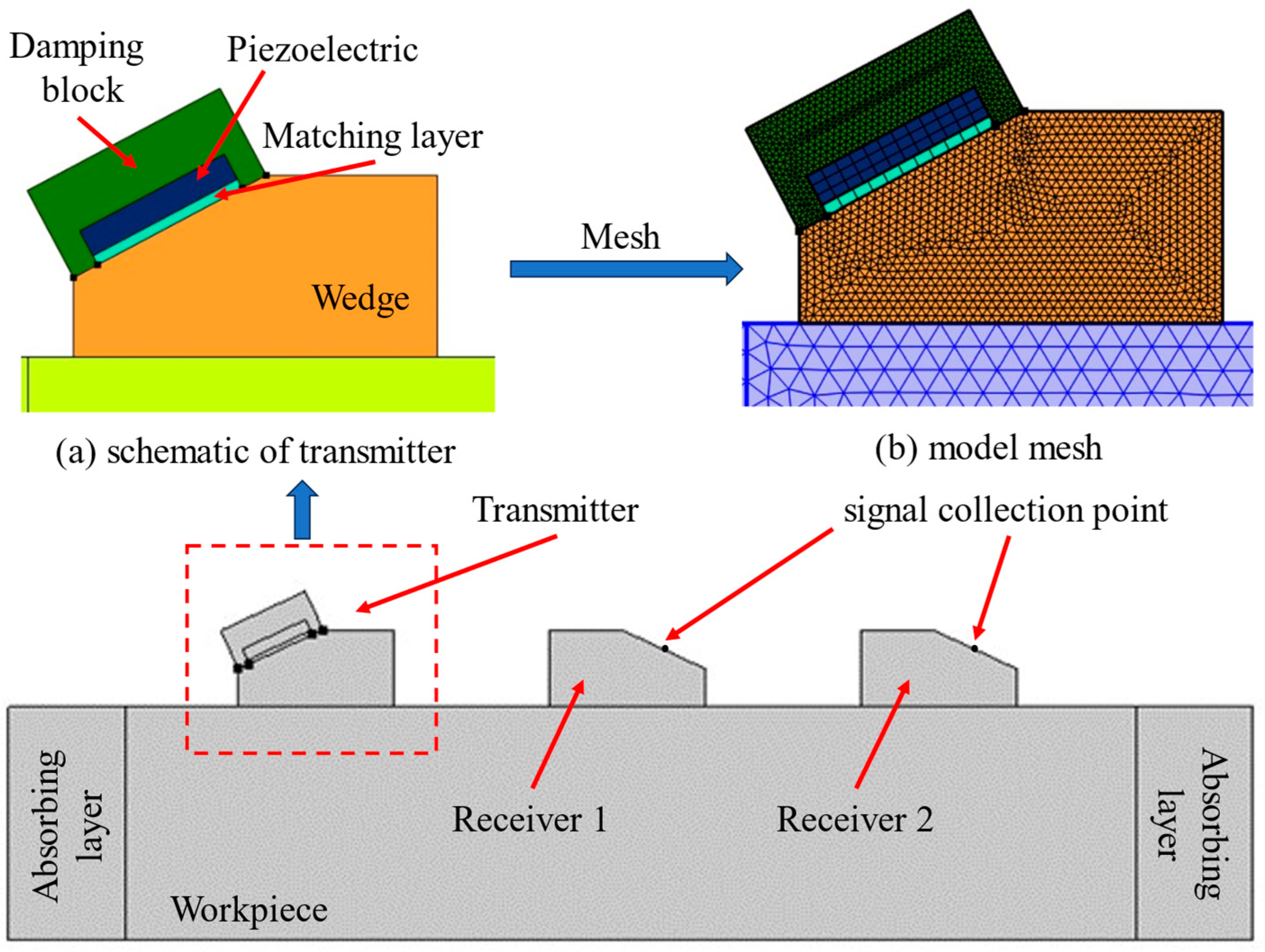

4.2. Design of OTDR Transducers

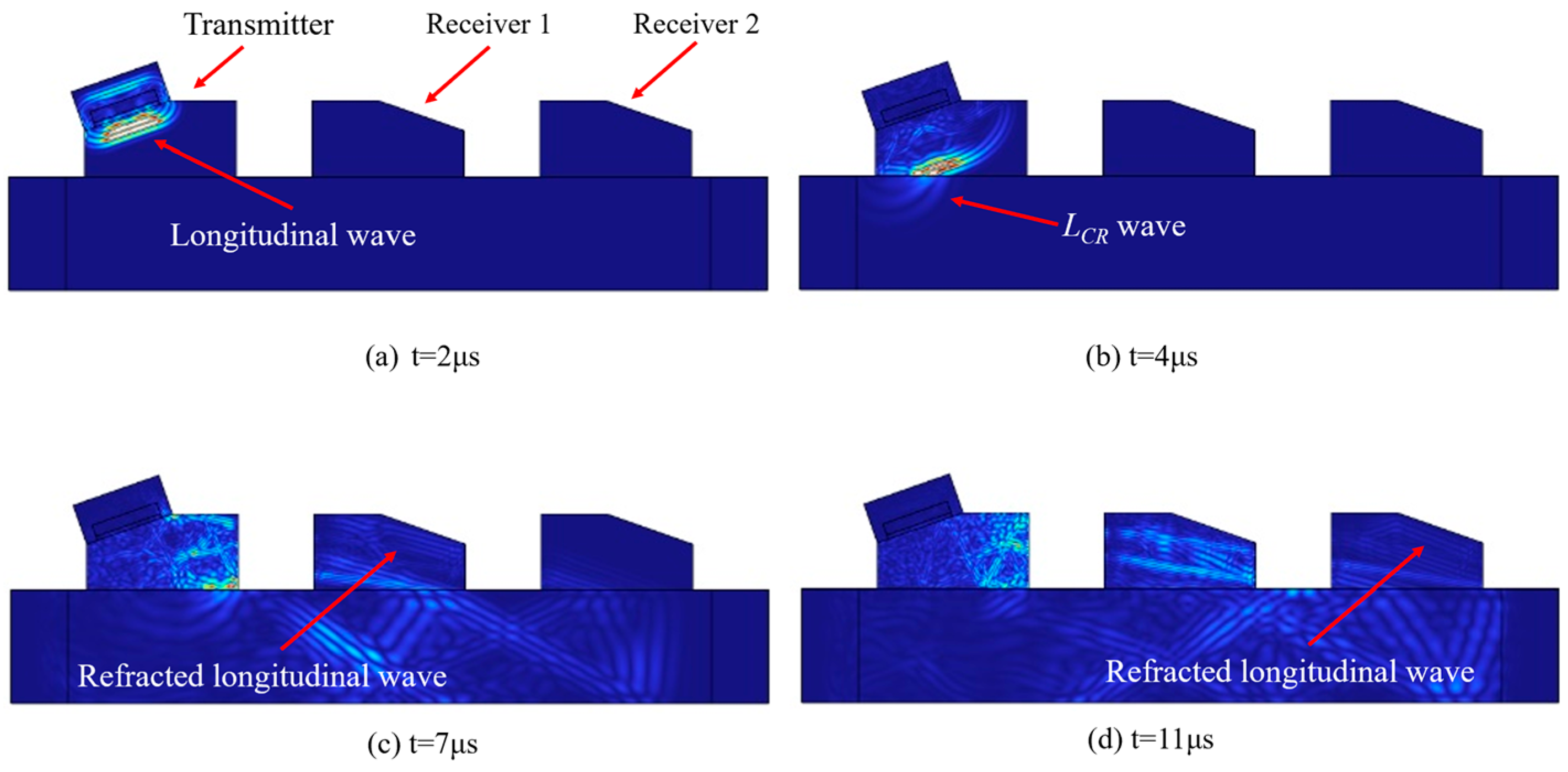

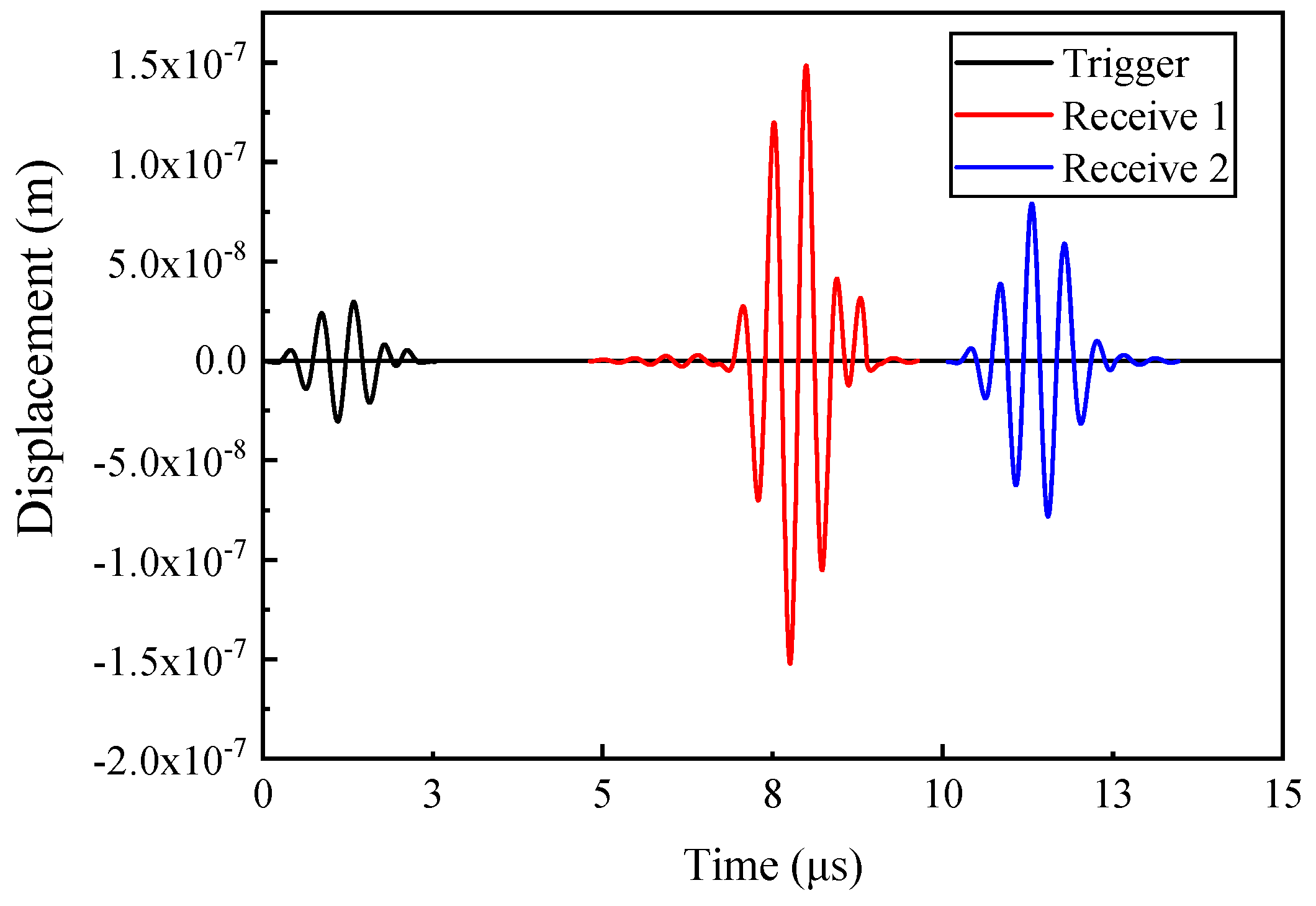

4.3. Verifying the Design with the FE Model

4.4. Design of the Detection Device

4.5. Calibration Experiment

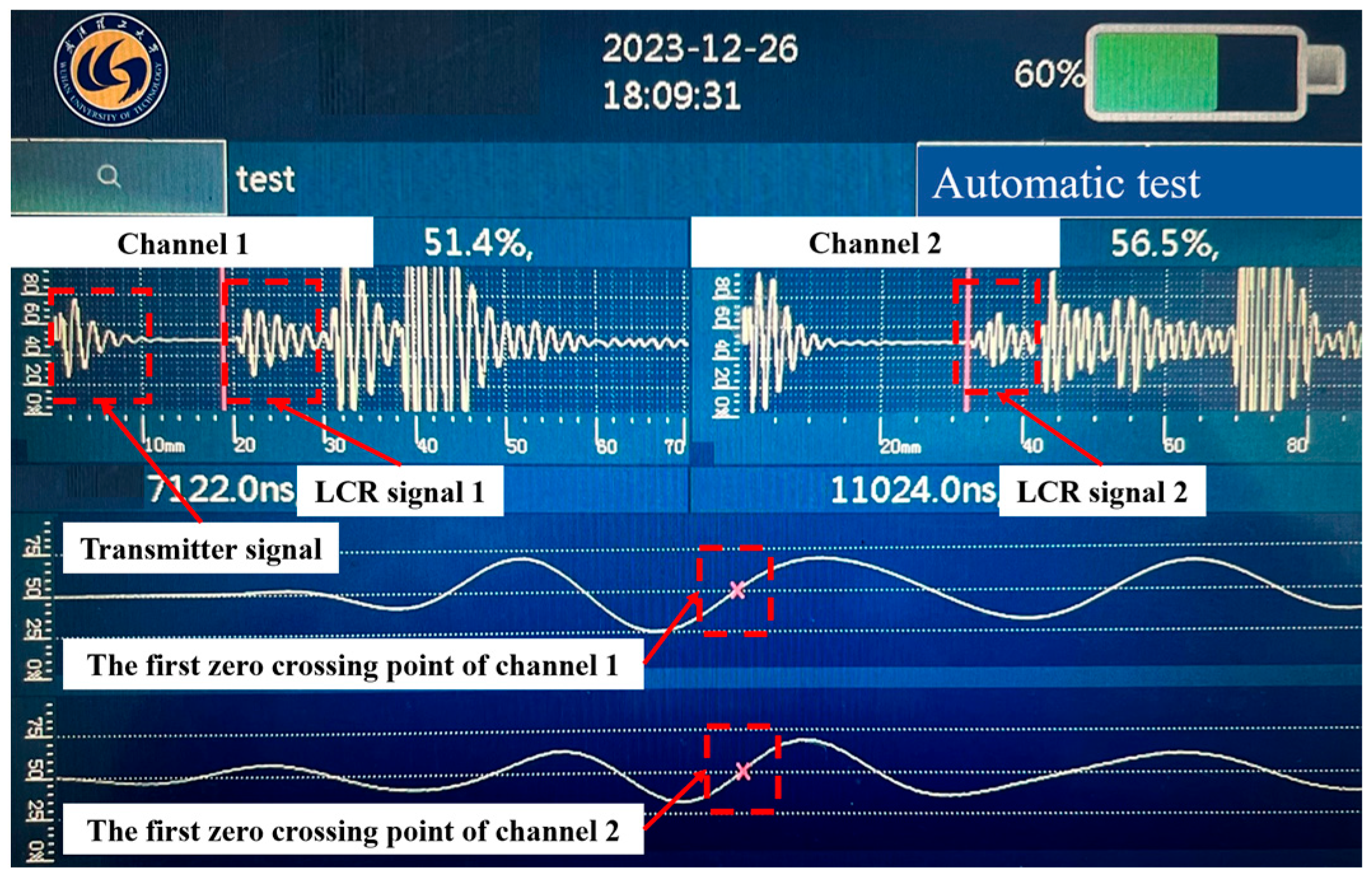

4.6. Residual Stress Detection Method

5. Results and Discussions

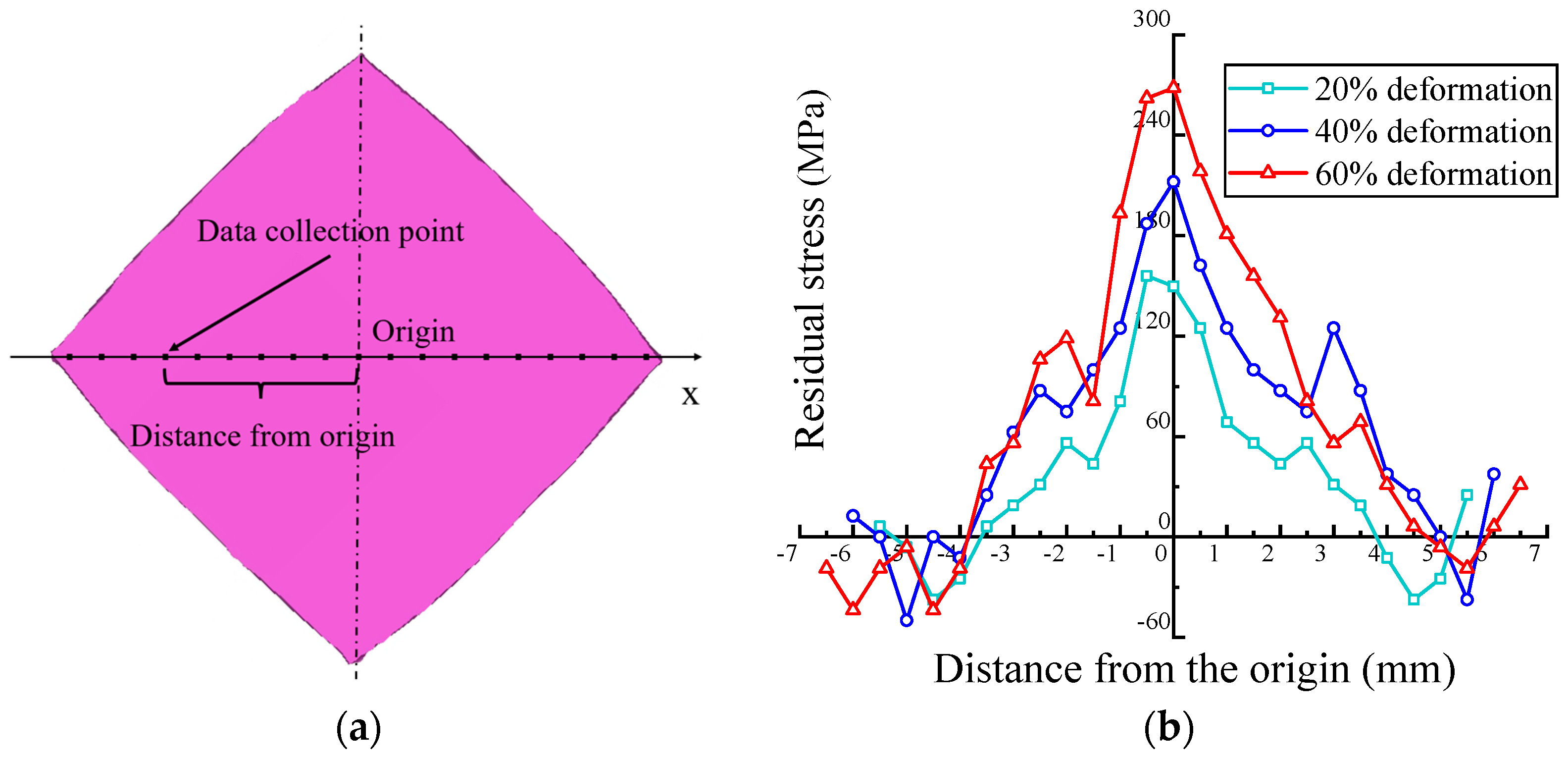

5.1. Effect of Deformation on Residual Stress

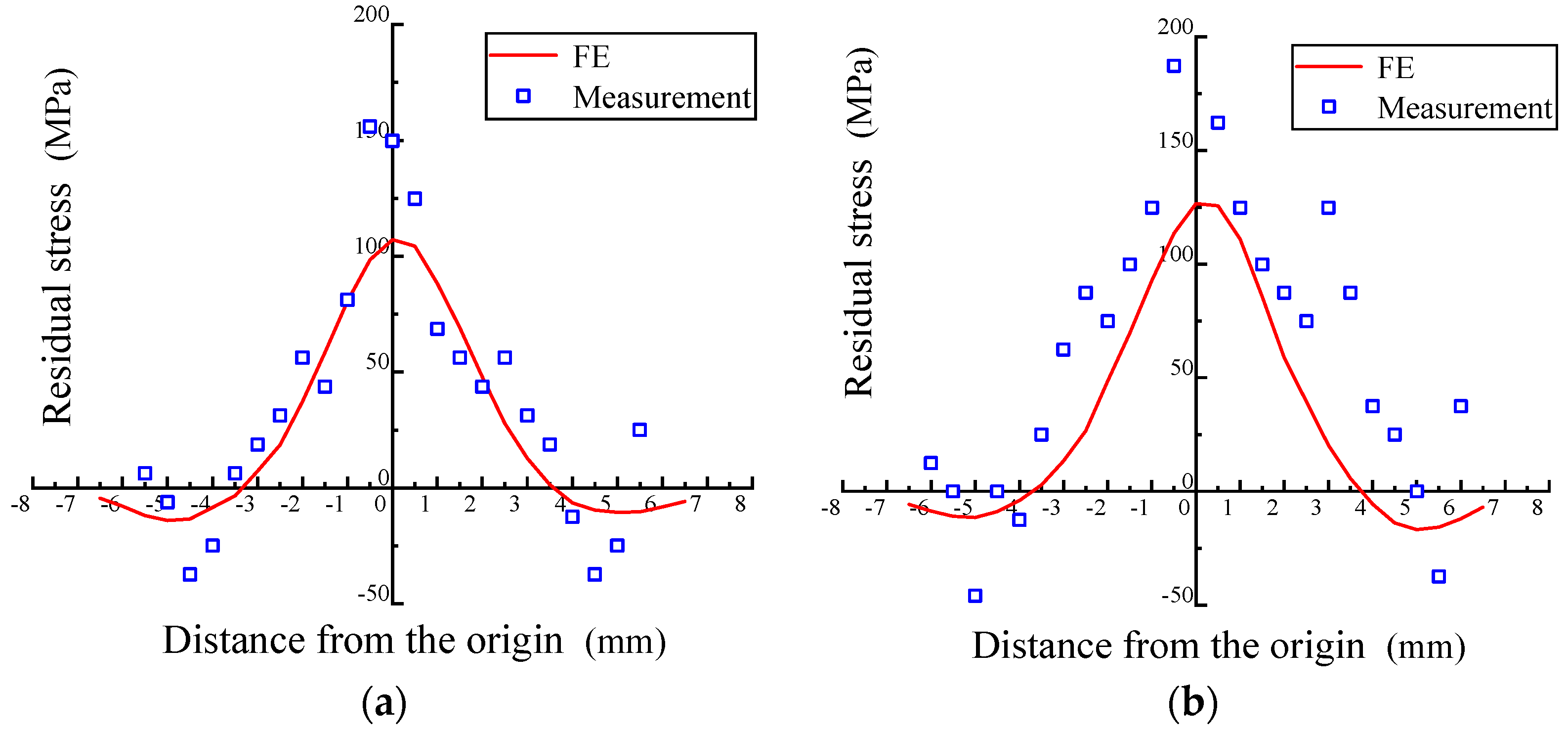

5.2. Comparison of the FE and Test Results

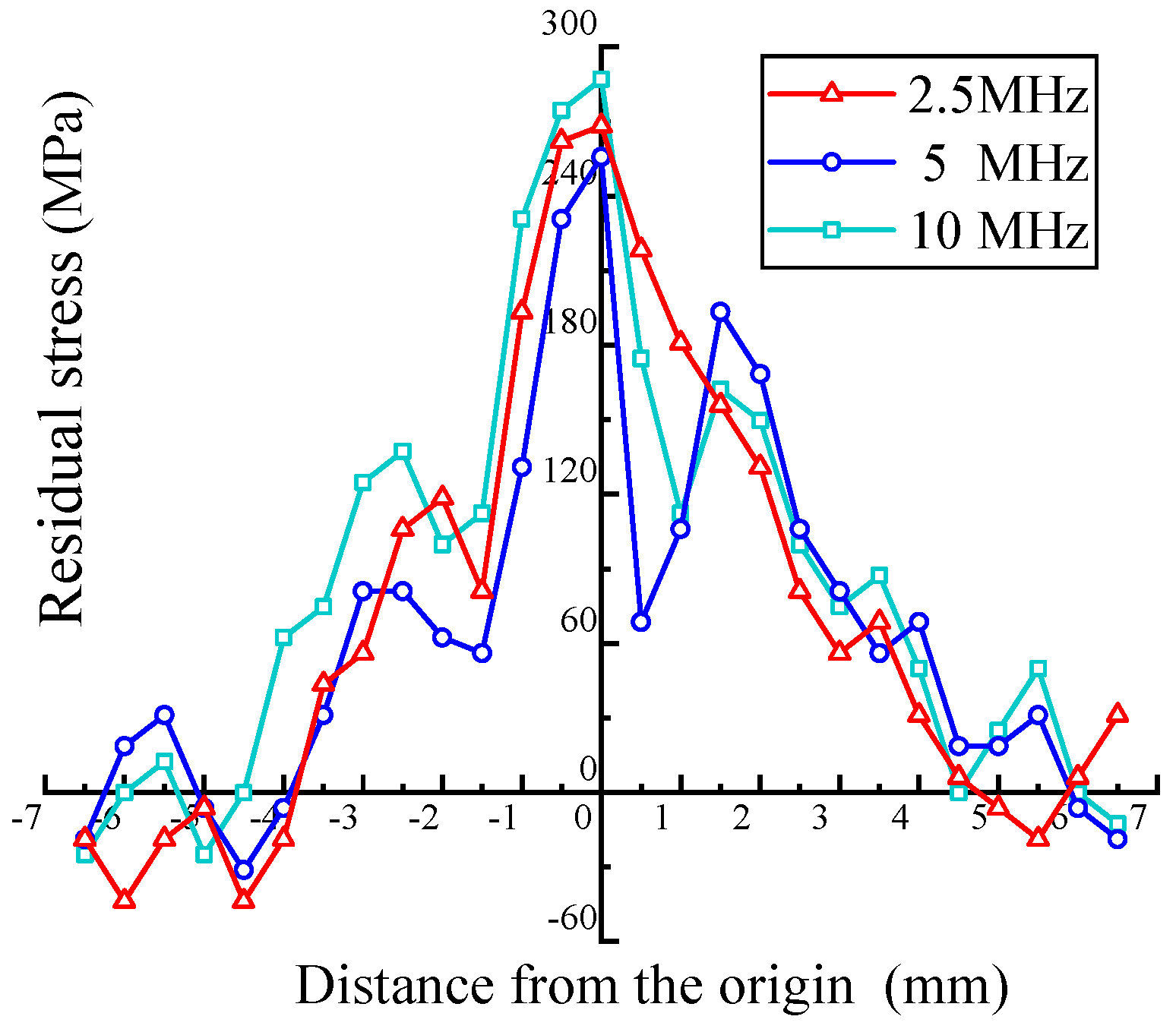

5.3. Distribution of the Residual Stress at Different Depths

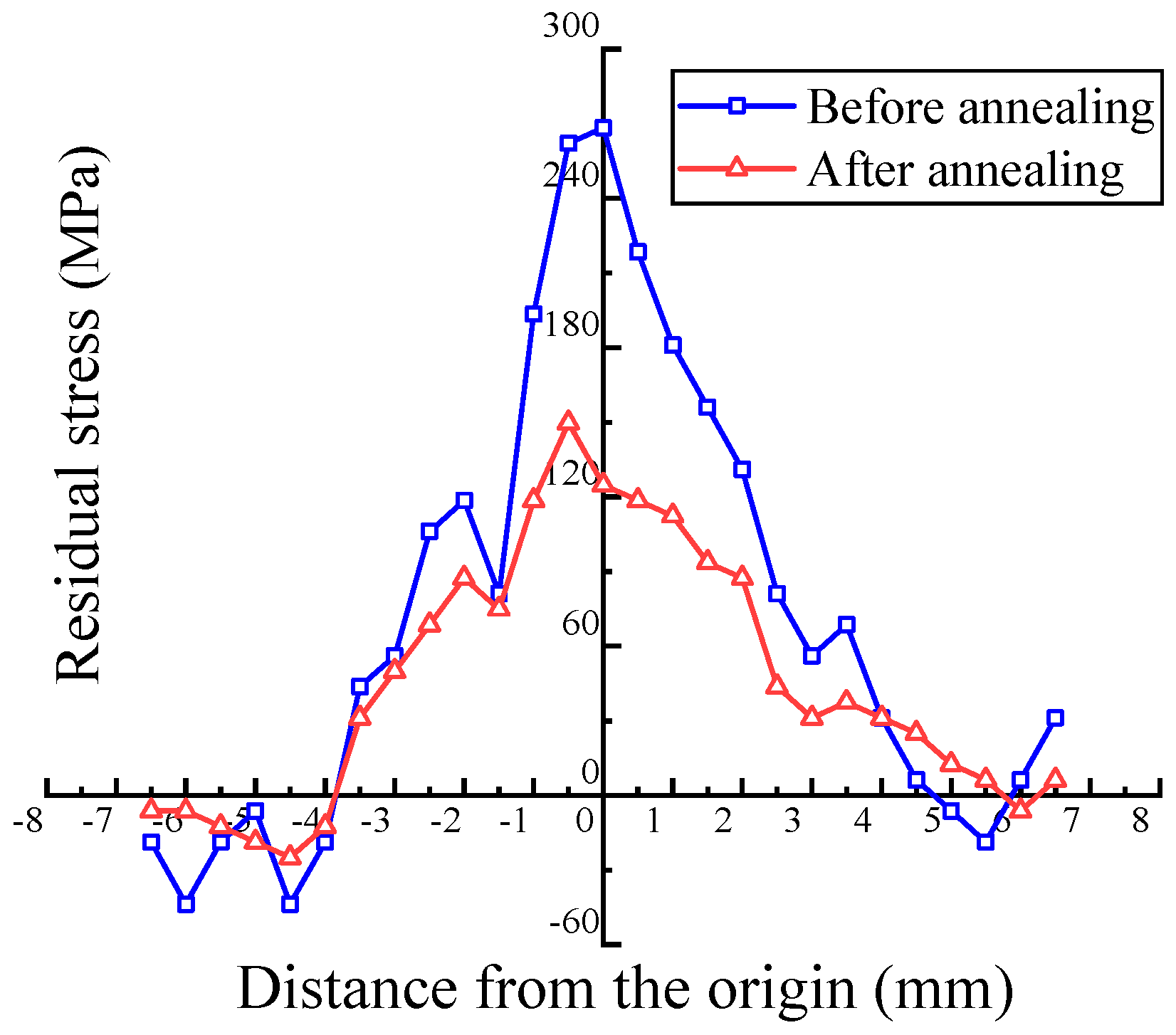

5.4. Residual Stress after Annealing

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The experimental results show that the residual stress of the rotary forging plate (6061 aluminum alloy) has an approximately centrosymmetric distribution, and the maximum and minimum values of stress appear at the center and edge of the workpiece, respectively. As the deformation increases from 20% to 60%, the peak residual tensile stress increases from 156 MPa to 262 MPa, and there is no significant difference in the peak compressive stress, which is around −40 MPa. The maximum deviation between measurement and FE is 61 MPa, which means the experimental data are similar to the FE results.

- (2)

- Transducers with frequencies of 2.5 MHz, 5 MHz, and 10 MHz were applied to obtain the residual stress distribution at different depths. When the deformation of the rotary forging plate reaches 60%, the difference in the residual stresses at different depths is less than 13%, which indicates that the plastic deformation zone basically penetrates the entire longitudinal cross-section of the aluminum alloy plate.

- (3)

- The peak value at the center of the plate after stress relief annealing is reduced by about 50% compared with that before, and the stress distribution becomes smoother, which means the risk of fatigue cracking at the center position is significantly reduced.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Symbol | Notation |

| The density of material under zero-stress | |

| V | The velocity of the longitudinal wave |

| λ, μ | The Lame elastic constants |

| l, m, n | The Murnaghan elastic constants |

| The stress of the workpiece being detected | |

| K | The acoustoelastic coefficient |

| The time variation under the condition of stress | |

| L | The distance between two receivers |

| L1 | The distance between the transmitter and the first receiver |

| L2 | The distance between the transmitter and the second receiver |

| The time delay of two receivers | |

| The acoustic time in wedge a | |

| The acoustic time in wedge b | |

| The acoustic time in wedge c | |

| The acoustic time in couplant under wedge a | |

| The acoustic time in couplant under wedge b | |

| The acoustic time in couplant under wedge c | |

| The acoustic time at distance L1 | |

| The acoustic time at distance L2 | |

| D | The penetration depth |

| The coefficient obtained by the experiment | |

| f | The frequency of the probe |

| γ | The inclination angle of the upper die |

| n’ | The oscillating speed of the upper die |

| v | The feed rate of the lower die |

| d | The maximum mesh size |

| CL | The longitudinal wave velocity of material |

| fS | The frequency of the excitation signal |

References

- Song, G.; Wang, Z.; Fan, X.; Liu, L. Research Progress of Aluminum Alloy Welding/Plastic Deformation Composite Forming Technology in Achieving High-Strength Joints. Materials 2023, 16, 7672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Han, X.; Hua, L.; Hu, X. An innovative constraining ring rolling process for manufacturing conical rings with thin sterna and high ribs. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Ma, C.; Zhang, G.; Qin, Y.; Cao, W. The Different Welding Layers and Heat Source Energy on Residual Stresses in Swing Arc Narrow Gap MAG Welding. Materials 2023, 16, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moazam, M.; Honarpisheh, M. The effects of combined cyclic close die forging and aging process on microstructure and mechanical properties of AA7075. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2020, 234, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.-N.; Li, X.-W.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y.-A.; Li, Z.-H.; Yan, H.-W.; Wen, K. Influence of Material Removal Strategy on Machining Deformation of Aluminum Plates with Asymmetric Residual Stresses. Materials 2023, 16, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Yin, J. Distribution of residual stress in an asymmetric T-section beam by stretch-bending. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 164, 105184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, M.; Liu, C.; Tang, K. An allowance allocation method based on dynamic approximation via online inspection data for deformation control of structural parts. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 3495–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S. Distortion caused by residual stresses in machining aeronautical aluminum alloy parts: Recent advances. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 89, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-S.; Yue, X.; Li, Q.-Y.; Peng, H.-L.; Dong, B.-X.; Liu, T.-S.; Yang, H.-Y.; Fan, J.; Shu, S.-L.; Qiu, F.; et al. Development and applications of aluminum alloys for aerospace industry. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 944–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, T.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Z. Study on Residual Stress and Optimization of Welding Parameters in Linear Friction Welding of TC17 Titanium Alloy. Materials 2022, 15, 8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fu, H.; Pan, B.; Kang, R. Recent progress of residual stress measurement methods: A review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 34, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, N.S.; Dassisti, M.; Benyounis, K.Y.; Olabi, A.G. Methods of measuring residual stresses in components. Mater. Des. 2011, 35, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, D.E.; Junghans, P.G. Application of the LCR ultrasonic technique for evaluation of post-weld heat treatment in steel plates. NDT&E Int. 1995, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Javadi, Y.; Sadeghi, S.; Najafabadi, A.M. Taguchi optimization and ultrasonic measurement of residual stresses in the friction stir welding. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashar, J.; Ahmadi, M.N. Comparison between contact and immersion ultrasonic method to evaluate welding residual stresses of dissimilar joints. Mater. Des. 2012, 47, 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Javadi, Y.; Plevris, V.; Najafabadi, M.A. Using LCR ultrasonic method to evaluate residual stress in dissimilar welded pipes. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2013, 4, 170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Javadi, Y.; Pirzaman, H.S.; Raeisi, M.H.; Najafabadi, M.A. Ultrasonic inspection of a welded stainless steel pipe to evaluate residual stresses through thickness. Mater. Des. 2013, 49, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, Y.; Hloch, S. Employing the LCR waves to measure longitudinal residual stresses in different depths of a stainless steel welded plate. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2013, 746187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, J.; Niu, G.; Liu, C.; Xiao, X. Application of Ultrasonic Residual Stress Measurement Technology in Engineering Practice. Hot Work. Technol. 2020, 49, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Y.-I.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.-I. Methodology for Mapping the Residual Stress Field in Serviced Rails Using LCR Waves. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2022, 41, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.S.; Kelly, J.L. Second-order elastic deformation of solids. Phys. Rev. 1953, 92, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Xu, C.; Pan, Q.; Song, J. Nondestructive testing and characterization of residual stress field using an ultrasonic method. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2016, 29, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Hua, L. 3D FE modelling of contact pressure response in cold rotary forging. Tribol. Int. 2013, 57, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Chen, L.; Hu, X.; Hua, L.; Chai, F. Microstructure and mechanical property evolution mechanisms of 15Cr14Co12Mo5Ni2WA aviation gear steel during cold rotary forging. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 3005–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Chen, W.; Hu, X.; Hua, L.; Chai, F. Grain Refinement Mechanism of 5A06 Aluminum Alloy Sheets during Cold Rotary Forging. Materials 2023, 16, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; He, B. Finite element simulation and experimental investigation of residual stresses in selective laser melted Ti–Ni shape memory alloy. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2016, 117, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6892-1:2009; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Xu, C.; Song, W.; Pan, Q.; Li, H.; Liu, S. Nondestructive Testing Residual Stress Using Ultrasonic Critical Refracted Longitudinal Wave. Phys. Procedia 2015, 70, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Han, X.; Chai, F.; Zhuang, W.; Zheng, F.; Yin, F.; Xie, L.; Hua, L. Efficiently manufacturing large-scale isotropic Al7075 alloy sheets with submicron grain by multidirectional rotary forging. Mater. Des. 2024, 238, 112713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, J.; Hu, X.; Hua, L.; Chai, F. Microstructure evolution and its influence mechanism on strength-plasticity of Al7075 sheets during hot multi-DoF forming. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 2698–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Han, X.; Hua, L.; Chai, F.; Zhuang, W.; Zheng, F.; Yin, F.; Wang, X. Strength-plasticity matching regulation of cold rotary forged Al5A06 sheets by annealing treatment and its influence on fatigue property. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 192, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Center Frequencies (MHz) | 2.5 | 5 | 10 |

| Penetration Depth (mm) | 2.7 | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Inclination angle of the upper die | 2° |

| Oscillating speed of the upper die | 240 r/min |

| Feed rate of the lower die | 1 mm/s |

| Friction factor between the dies and workpiece | 0.14 |

| Part | Material | Density (kg/m3) | Longitudinal Wave Speed (m/s) | Shear Wave Speed (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric | PZT-5H | 7500 | 4620 | 1750 |

| Wedge | Acrylic plastic | 1190 | 2080 | 1000 |

| Matching layer | Alumina/Epoxy | 2280 | 3400 | 1920 |

| Damping block | Tungsten/Epoxy | 6580 | 1500 | 775 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Han, X.; Zheng, F.; Yan, W. Ultrasonic Non-Destructive Detection Method for Residual Stress in Rotary Forging Aluminum Alloy Plates. Materials 2024, 17, 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112528

Chen H, Wang X, Han X, Zheng F, Yan W. Ultrasonic Non-Destructive Detection Method for Residual Stress in Rotary Forging Aluminum Alloy Plates. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112528

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Hongyu, Xiaokai Wang, Xinghui Han, Fangyan Zheng, and Wenlong Yan. 2024. "Ultrasonic Non-Destructive Detection Method for Residual Stress in Rotary Forging Aluminum Alloy Plates" Materials 17, no. 11: 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112528

APA StyleChen, H., Wang, X., Han, X., Zheng, F., & Yan, W. (2024). Ultrasonic Non-Destructive Detection Method for Residual Stress in Rotary Forging Aluminum Alloy Plates. Materials, 17(11), 2528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112528