Optimization of Magnetic Tunnel Junction Structure through Component Analysis and Deposition Parameters Adjustment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

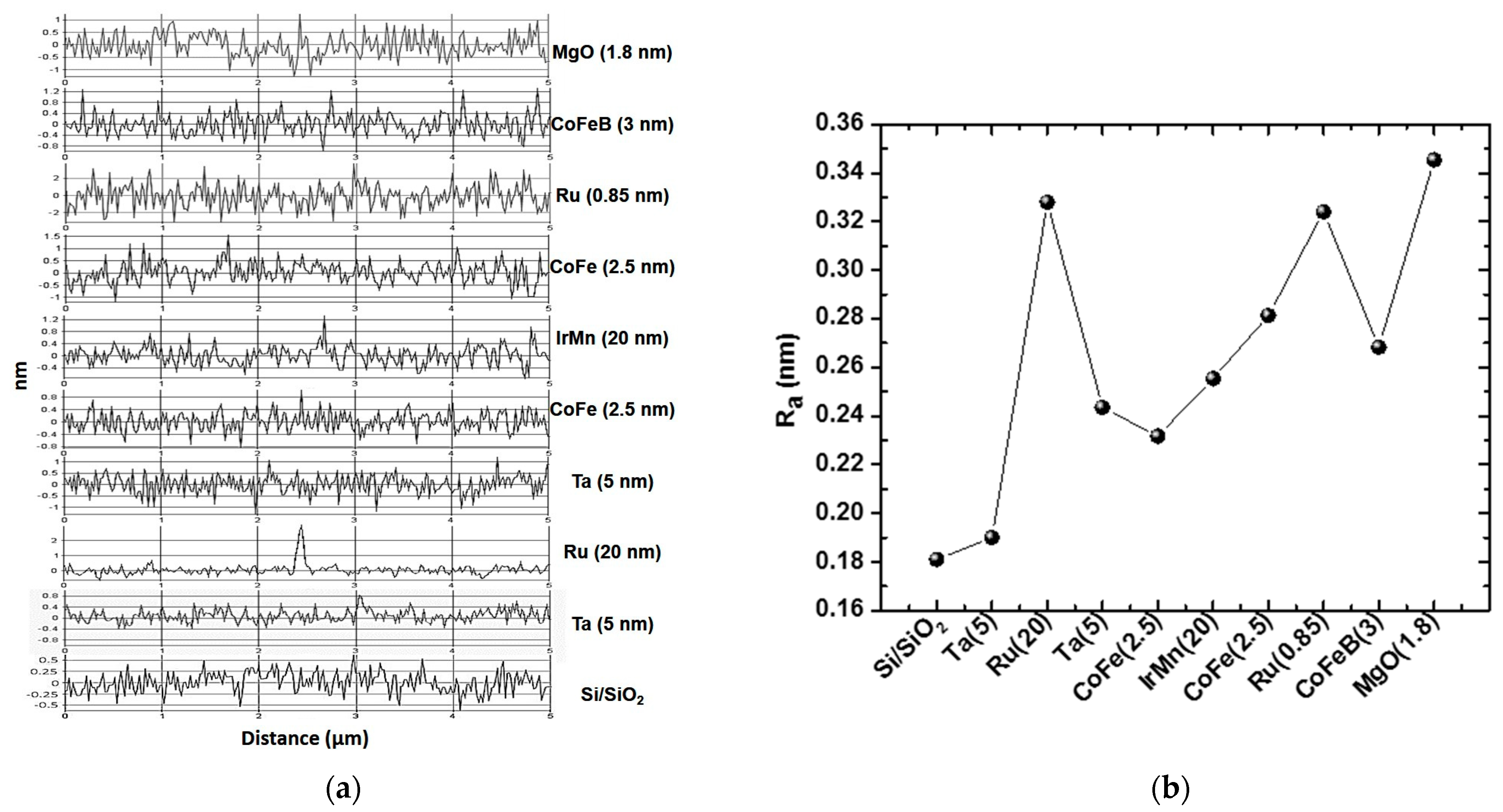

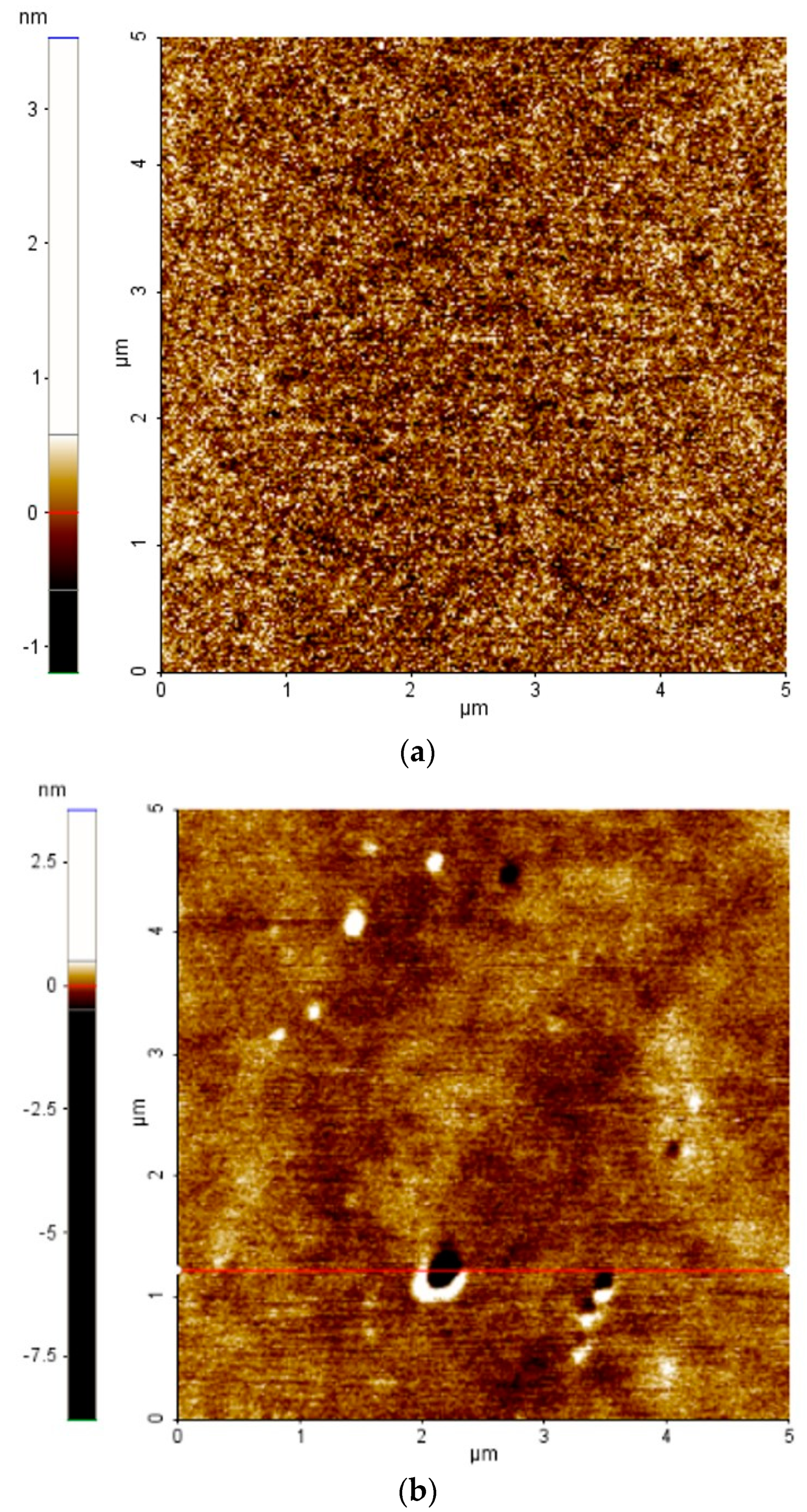

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

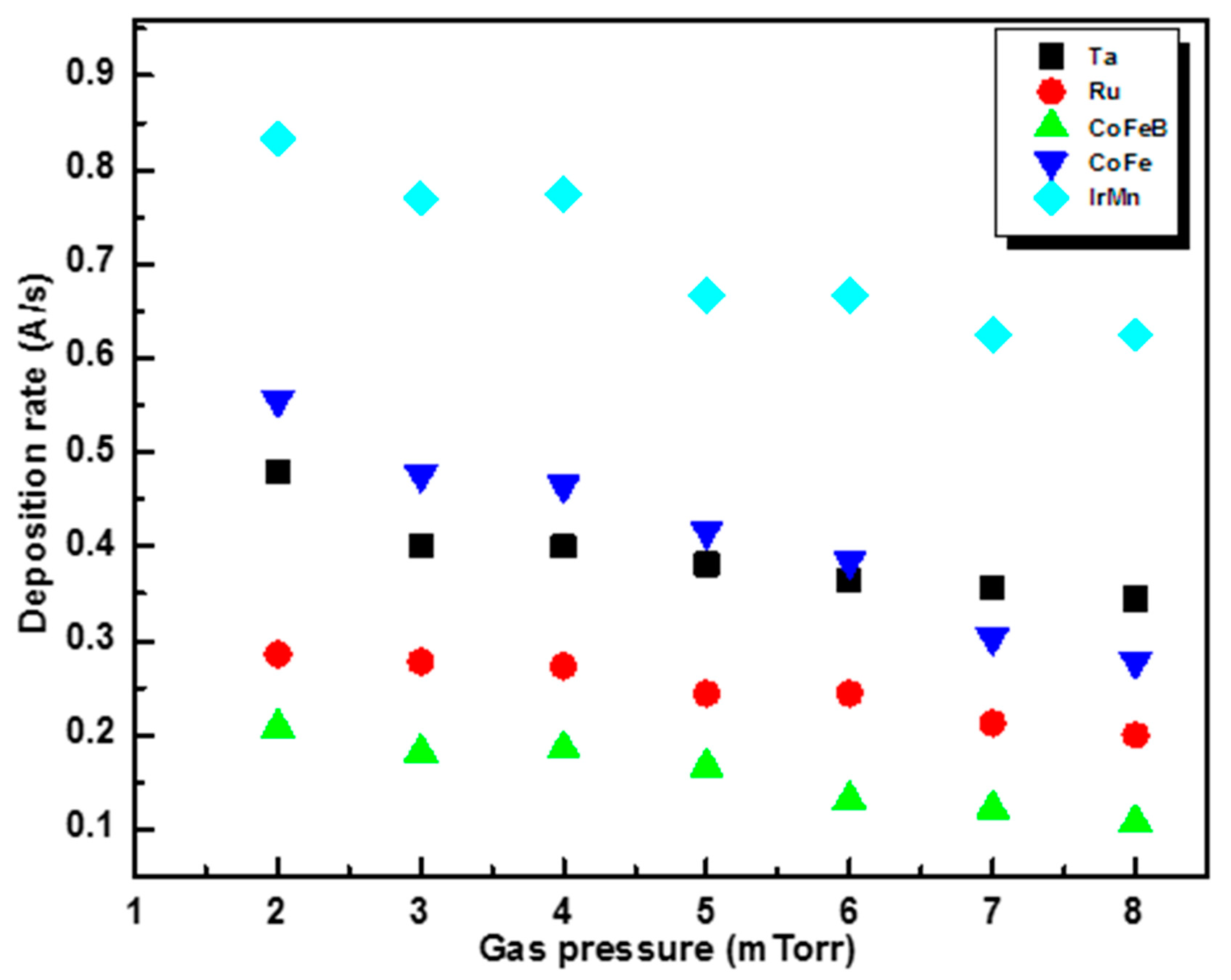

3.1. Working Gas Pressure

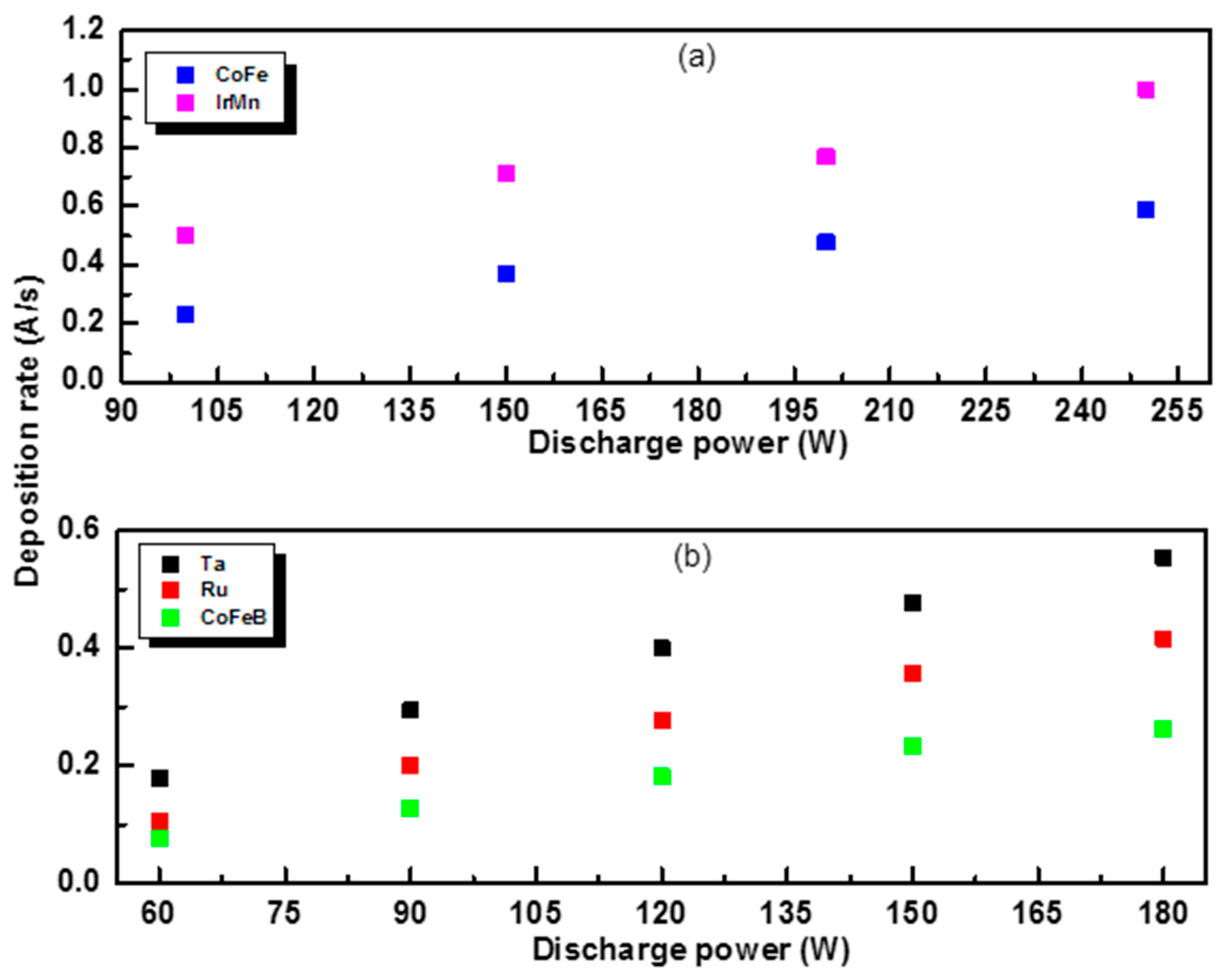

3.2. Discharge Power

3.3. Target–Substrate Distance

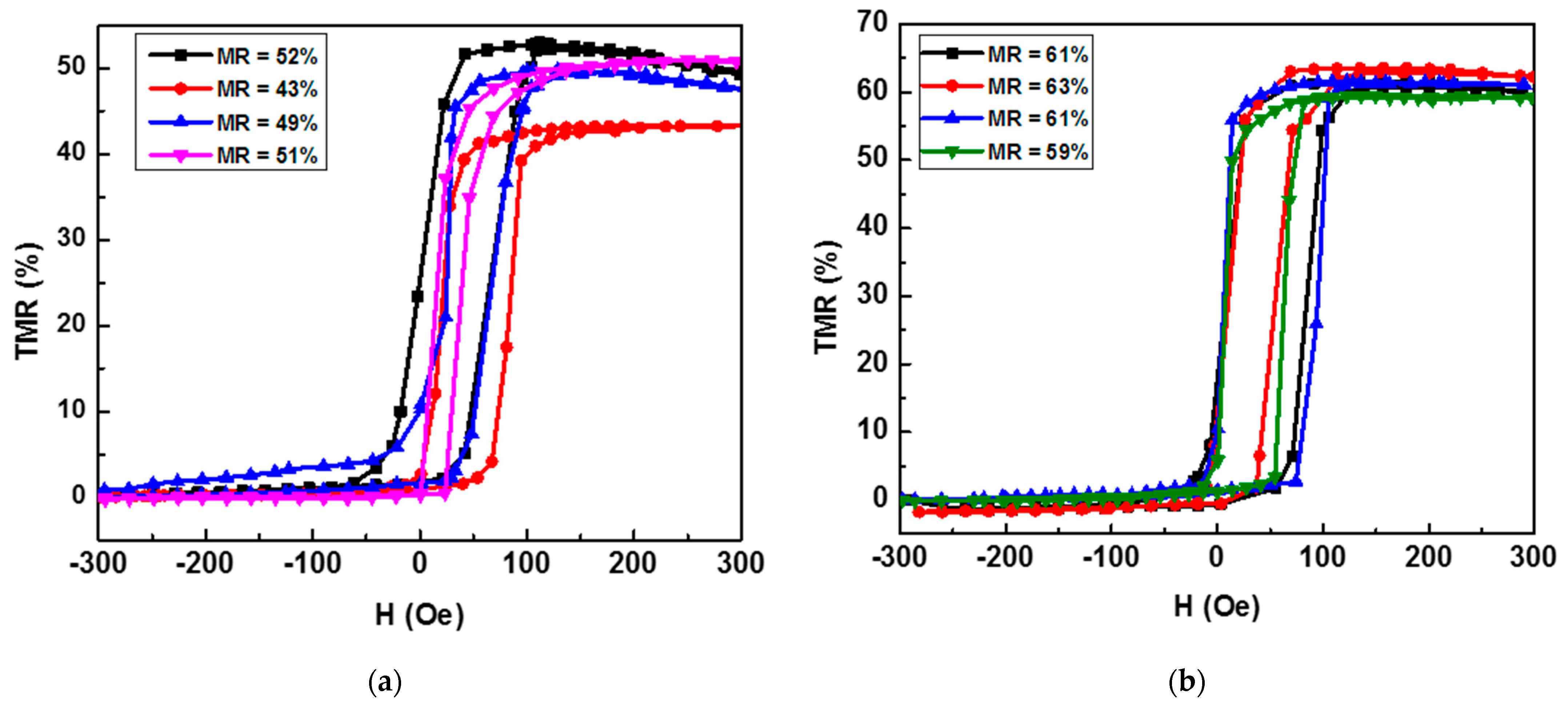

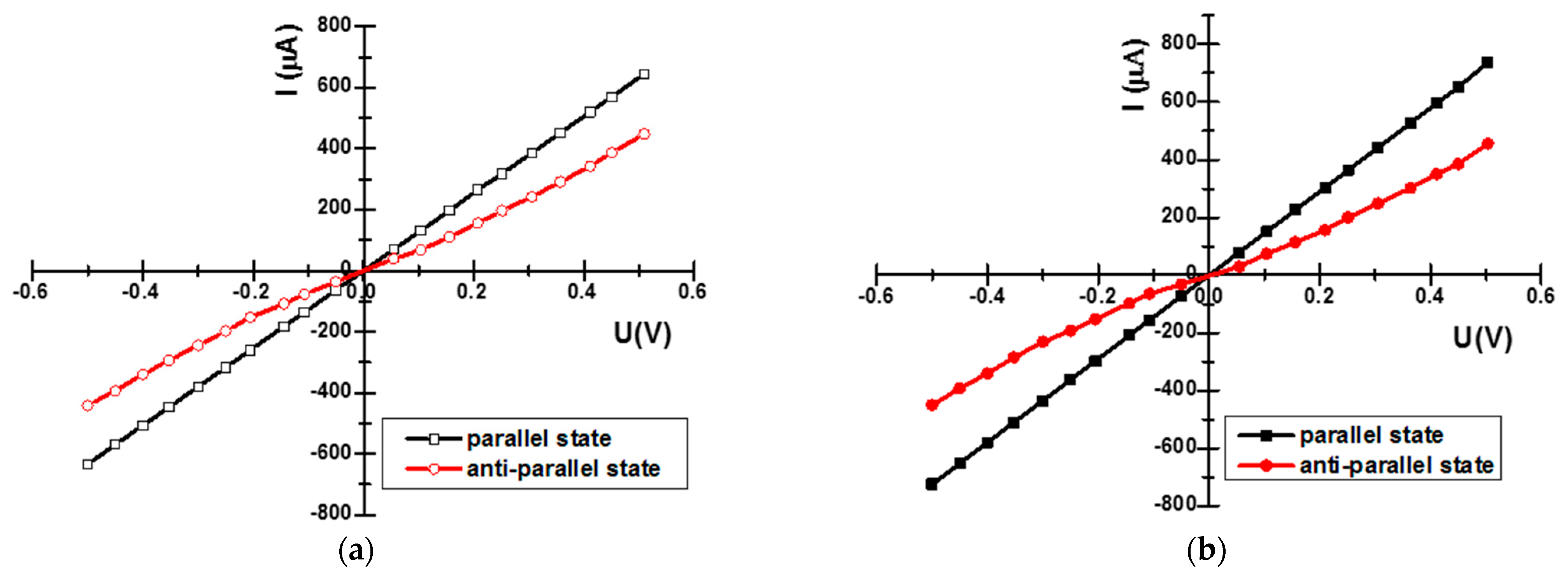

3.4. Performance of the Magnetic-Tunnel-Junction-Based Structure

- Definition of an MTJ structure in a rectangular shape with dimensions of 40 × 80 μm2 using electron-beam lithography (EBL) and ion-beam etching (IBE). The detection element and the bottom contact are then defined on this rectangular structure.

- Definition of the bottom contact by EBL and IBE followed by resist stripping.

- Definition of the rectangular (4 × 8 μm2) detection element with EBL and IBE. In this stage, the surface of the bottom contact is protected by e-resist in the same lithography step as the detection element (pillar).

- In order to prevent electrical contact between the bottom contact and the top surface of the MTJ, a 40 nm thick SiO2 insulating layer was deposited on the chip surface by sputtering, followed by a lift-off process.

- Fabrication of the electrical contacts by laser-beam lithography and deposition of Ta (5 nm)/Cu (200 nm).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomson, W. On the Electro-Dynamic Qualities of Metals:—Effects of Magnetization on the Electric Conductivity of Nickel and of Iron. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1857, 8, 546–550. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, A.M. Magnetic Sensors and Geometrical Magnetoresistance: A Review. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 2020, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.K.C. Magneto-Resistance in Metals. Phil. Mag. 1957, 2, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.V.; Isin, A. Magnetoresistance in Iron Single Crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 1966, 37, 1028–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitao, D.C.; Paz, E.; Silva, A.V.; Moskaltsova, A.; Knudde, S.; Deepak, F.L.; Ferreira, R.; Cardoso, S.; Freitas, P.P. Nanoscale Magnetic Tunnel Junction Sensing Devices with Soft Pinned Sensing Layer and Low Aspect Ratio. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, S.S.P.; Kaiser, C.; Panchula, A.; Rice, P.M.; Hughes, B.; Samant, M.; Yang, S.-H. Giant Tunnelling Magnetoresistance at Room Temperature with MgO (100) Tunnel Barriers. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 862–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuasa, S.; Nagahama, T.; Fukushima, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Ando, K. Giant Room-Temperature Magnetoresistance in Single-Crystal Fe/MgO/Fe Magnetic Tunnel Junctions. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, X.; Xu, B.; Lu, P.; Patwari, M.; Xi, H.; Chang, C.; Miller, B.; et al. Commercial TMR Heads for Hard Disk Drives: Characterization and Extendibility at 300 Gbit2. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2006, 42, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Xi, H.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, W. Design Margin Exploration of Spin-Transfer Torque RAM (STT-RAM) in Scaled Technologies. IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst. 2010, 18, 1724–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubells, M.D.; Reig, C.; De Marcellis, A.; Roldan, A.; Roldan, J.-B.; Cardoso, S.; Freitas, P.P. Magnetic Tunnel Junction (MTJ) Sensors for Integrated Circuits (IC) Electric Current Measurement. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE SENSORS, Baltimore, MD, USA, 3–6 November 2013; IEEE: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Grancharov, S.G.; Zeng, H.; Sun, S.; Wang, S.X.; O’Brien, S.; Murray, C.B.; Kirtley, J.R.; Held, G.A. Bio-Functionalization of Monodisperse Magnetic Nanoparticles and Their Use as Biomolecular Labels in a Magnetic Tunnel Junction Based Sensor. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 13030–13035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.Q.; Li, L.; Li, G.J.; Leung, C.W.; Shi, J.; Wong, C.M.; Lo, K.C.; Chan, W.K.; Mak, C.S.K.; Chan, S.B.; et al. Liver Cancer Immunoassay with Magnetic Nanoparticles and MgO-Based Magnetic Tunnel Junction Sensors. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 07E505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Schrag, B.D.; Carter, M.J.; Xie, J.; Xu, C.; Sun, S.; Xiao, G. Detection of DNA Labeled with Magnetic Nanoparticles Using MgO-Based Magnetic Tunnel Junction Sensors. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 07A306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, S.; Djayaprawira, D.D. Giant Tunnel Magnetoresistance in Magnetic Tunnel Junctions with a Crystalline MgO (0 0 1) Barrier. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2007, 40, R337–R354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.W.; Lee, W.W.; Lee, J.G.; Lee, C.M. A Comparison of the Mechanical Properties of RF- and DC-Sputter-Deposited Cr Thin Films. Mater. Sci. Forum 2007, 546–549, 1695–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaiesh, A.; Holland, L. The Dependence of Deposition Rate on Power Input for Dc and Rf Magnetron Sputtering. Vacuum 1981, 31, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, S.; Vaghri, E.; Daemi, M.; Esmaili, P.; Ramezani, A.H.; Memon, S.; Hoseinzadeh, S. Magnetron Sputtering Technique for Analyzing the Influence of RF Sputtering Power on Microstructural Surface Morphology of Aluminum Thin Films Deposited on SiO2/Si Substrates. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhang, C.; Chu, J. The Effect of Working Gas Pressure and Deposition Power on the Properties of Molybdenum Films Deposited by DC Magnetron Sputtering. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2014, 57, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, N.; Chelvanathan, P.; Zaman, M.; Sopian, K.; Amin, N. An Investigation on Structural and Electrical Properties of RF-Sputtered Molybdenum Thin Film Deposited on Different Substrates. Energy Procedia 2013, 33, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.; Hayakawa, J.; Lee, Y.M.; Matsukura, F.; Ohno, Y.; Hanyu, T.; Ohno, H. Magnetic Tunnel Junctions for Spintronic Memories and Beyond. IEEE Trans. Electron Dev. 2007, 54, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, T.; Ito, K.; Takemura, R.; Ohno, H. Spin-Transfer Torque RAM Technology: Review and Prospect. Microelectron. Reliab. 2012, 52, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, G.F.; Rodriguez, J.G.; Calle, F. Effect of Substrate–Target Distance and Sputtering Pressure in the Synthesis of AlN Thin Films. Microsyst. Technol. 2011, 17, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H.; Boo, J.H. Influence of Target-to-Substrate Distance on the Properties of AZO Films Grown by RF Magnetron Sputtering. Thin Solid Films 2004, 447–448, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakushiji, K.; Kubota, H.; Fukushima, A.; Yuasa, S. Perpendicular Magnetic Tunnel Junctions with Strong Antiferromagnetic Interlayer Exchange Coupling at First Oscillation Peak. Appl. Phys. Express 2015, 8, 083003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.J.; Lim, S.H.; Lee, S.-R. Strong Interlayer Exchange Coupling and High Post-Annealing Stability in Perpendicularly Magnetized [Pt/Co]/Ru/[Co/Pt] Structures. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 025112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.F.; Feng, G.; Ma, Q.L.; Han, X.F.; Coey, J.M.D. Temperature Dependence of Inverted Tunneling Magnetoresistance in MgO-Based Magnetic Tunnel Junctions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322, 1446–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniowski, P.; Almeida, J.M.; Cardoso, S.; Barradas, N.P.; Freitas, P.P. Effect of Free Layer Thickness and Shape Anisotropy on the Transfer Curves of MgO Magnetic Tunnel Junctions. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 07A910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.; Sbiaa, R.; Hirohata, A.; Ohno, H.; Fukami, S.; Piramanayagam, S.N. Spintronics Based Random Access Memory: A Review. Mater. Today 2017, 20, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-G.; Li, M.; Hageman, S.; Chien, C.L. Electric-Field-Assisted Switching in Magnetic Tunnel Junctions. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, H.; Oguz, K.; Niizeki, T.; Coey, J.M.D. Giant Tunneling Magnetoresistance with Electron Beam Evaporated MgO Barrier and CoFeB Electrodes. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 083920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Z.; Feng, J.F.; Kurt, H.; Feng, G.; Coey, J.M.D. Reduced Low Frequency Noise in Electron Beam Evaporated MgO Magnetic Tunnel Junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 202506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.; Ventura, J.; Ferreira, R.; Freitas, P.P. Optimization of the Buffer Surface of CoFeB/MgO/CoFeB-Based Magnetic Tunnel Junctions by Ion Beam Milling. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 424, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Katayama, T.; Ando, K. Characterization of Growth and Crystallization Processes in CoFeB/MgO/CoFeB Magnetic Tunnel Junction Structure by Reflective High-Energy Electron Diffraction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 242503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thin Film | Role in MTJ Structure | Properties | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ta | Capping layer |

| |

| CoFeB | Free layer |

| |

| MgO | Tunnel layer |

| |

| CoFeB | Synthetic antiferromagnetic (SAFM) | Reference layer |

|

| Ru | Barrier layer in SAFM |

| |

| CoFe | Pinned layer |

| |

| IrMn | Antiferromagnetic layer |

| |

| CoFe | Seed layer |

| |

| Ta | Buffer layer |

| |

| Ru | Buffer layer |

| |

| Ta | Buffer layer |

| |

| Si/SiO2 | Substrate |

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghemes, C.; Tibu, M.; Dragos-Pinzaru, O.-G.; Ababei, G.; Stoian, G.; Lupu, N.; Chiriac, H. Optimization of Magnetic Tunnel Junction Structure through Component Analysis and Deposition Parameters Adjustment. Materials 2024, 17, 2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112554

Ghemes C, Tibu M, Dragos-Pinzaru O-G, Ababei G, Stoian G, Lupu N, Chiriac H. Optimization of Magnetic Tunnel Junction Structure through Component Analysis and Deposition Parameters Adjustment. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112554

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhemes, Crina, Mihai Tibu, Oana-Georgiana Dragos-Pinzaru, Gabriel Ababei, George Stoian, Nicoleta Lupu, and Horia Chiriac. 2024. "Optimization of Magnetic Tunnel Junction Structure through Component Analysis and Deposition Parameters Adjustment" Materials 17, no. 11: 2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112554