Separation of Adjacent Light Rare Earth Elements Using Silica Gel Modified with Diglycolamic Acid

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

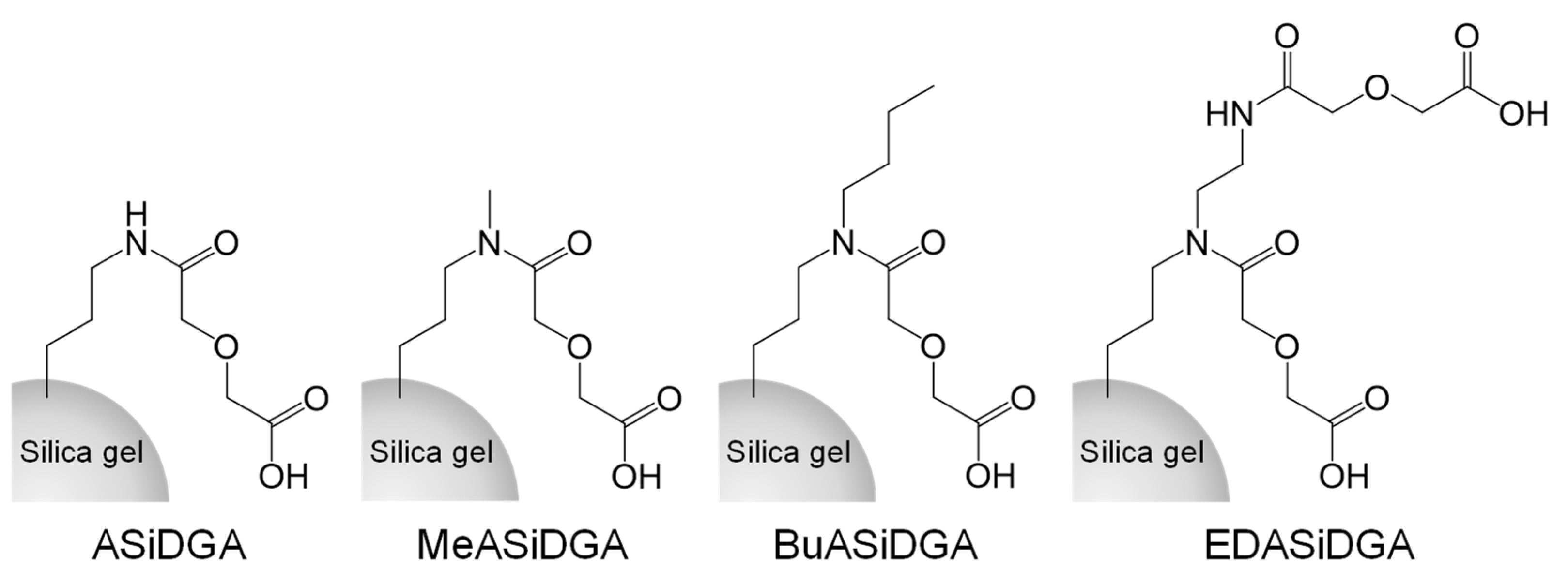

2.2. Preparation of Adsorbents

2.3. Procedure of Batch Adsorption Tests

2.4. Procedure of Column Separation

3. Results and Discussion

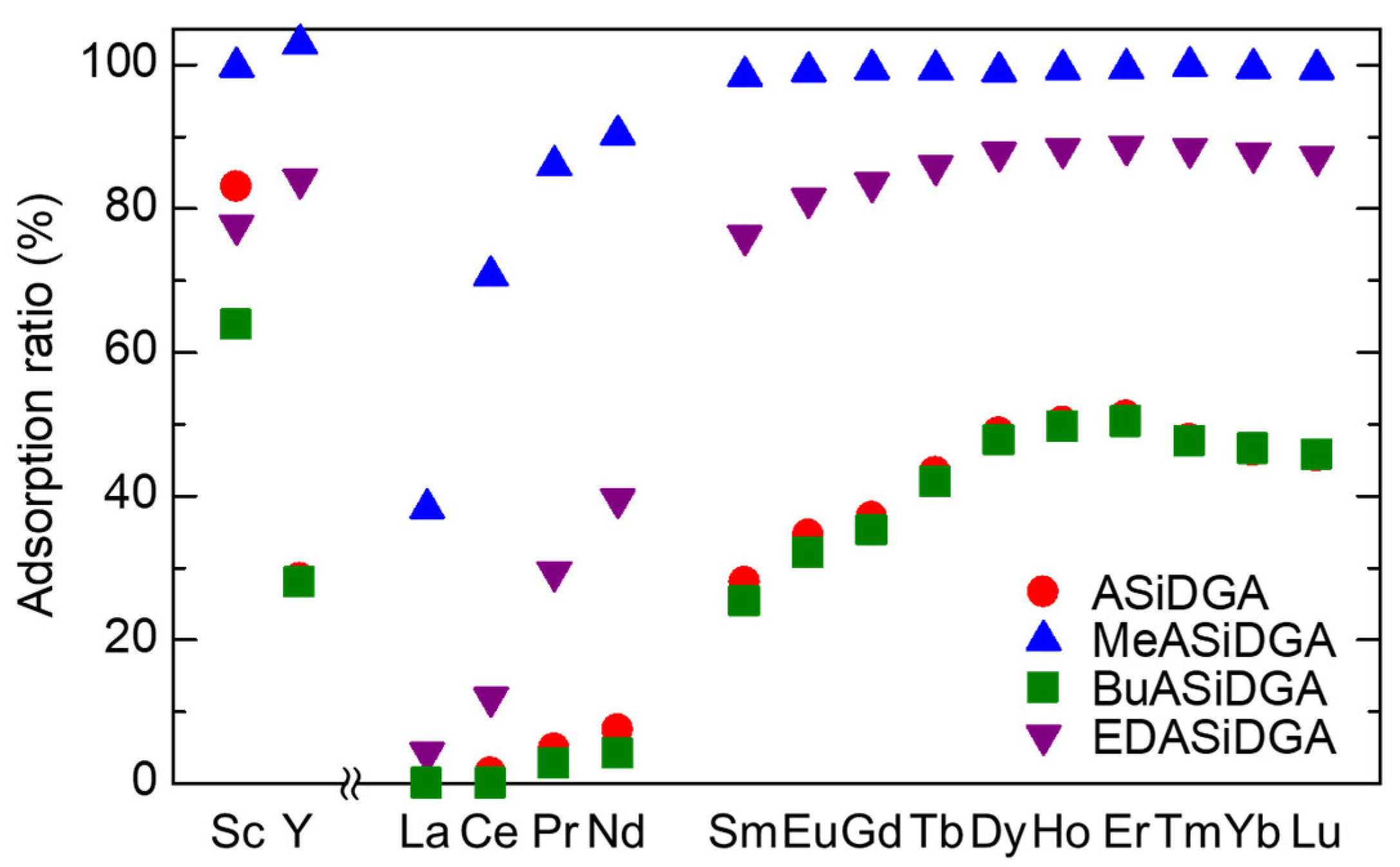

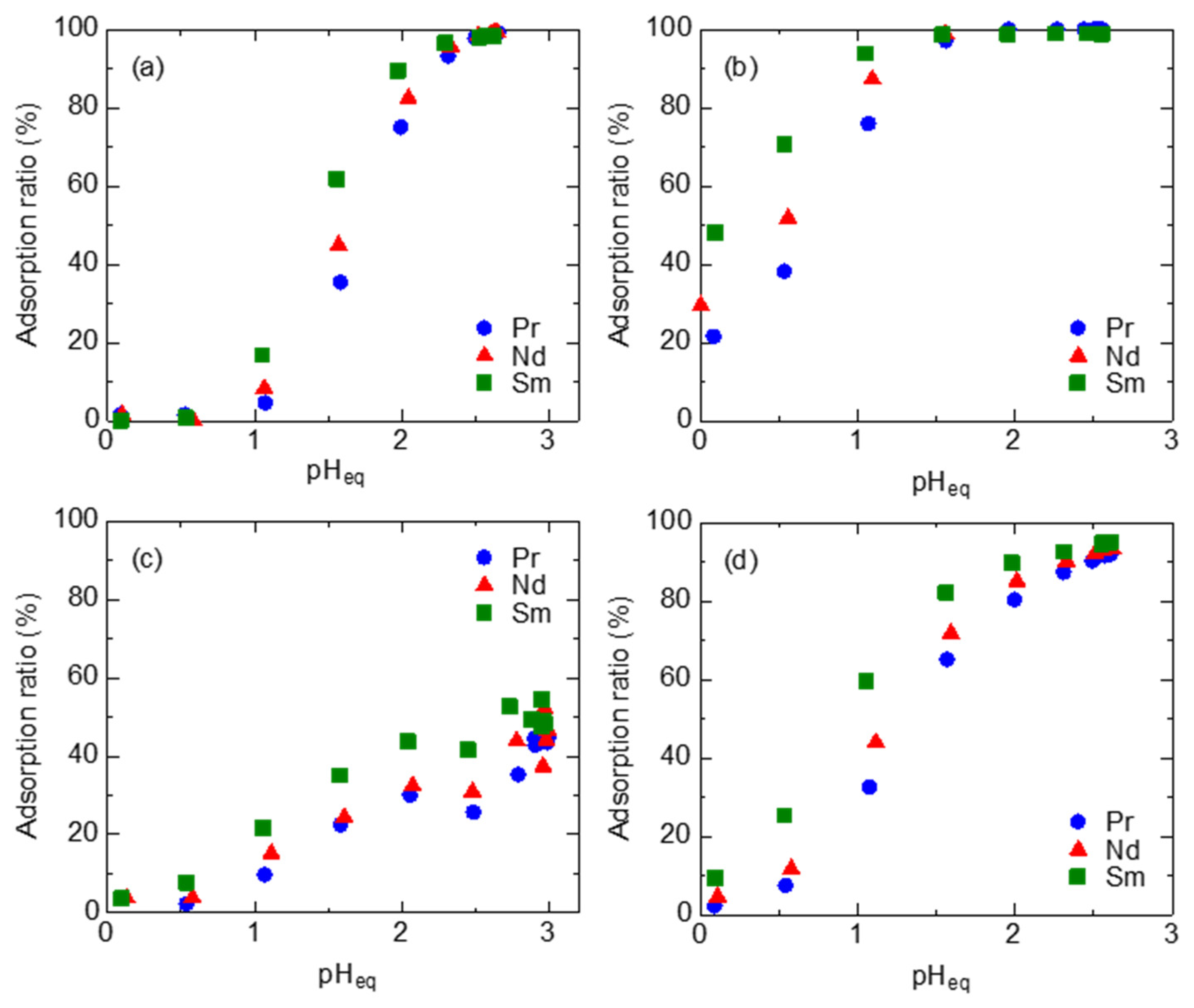

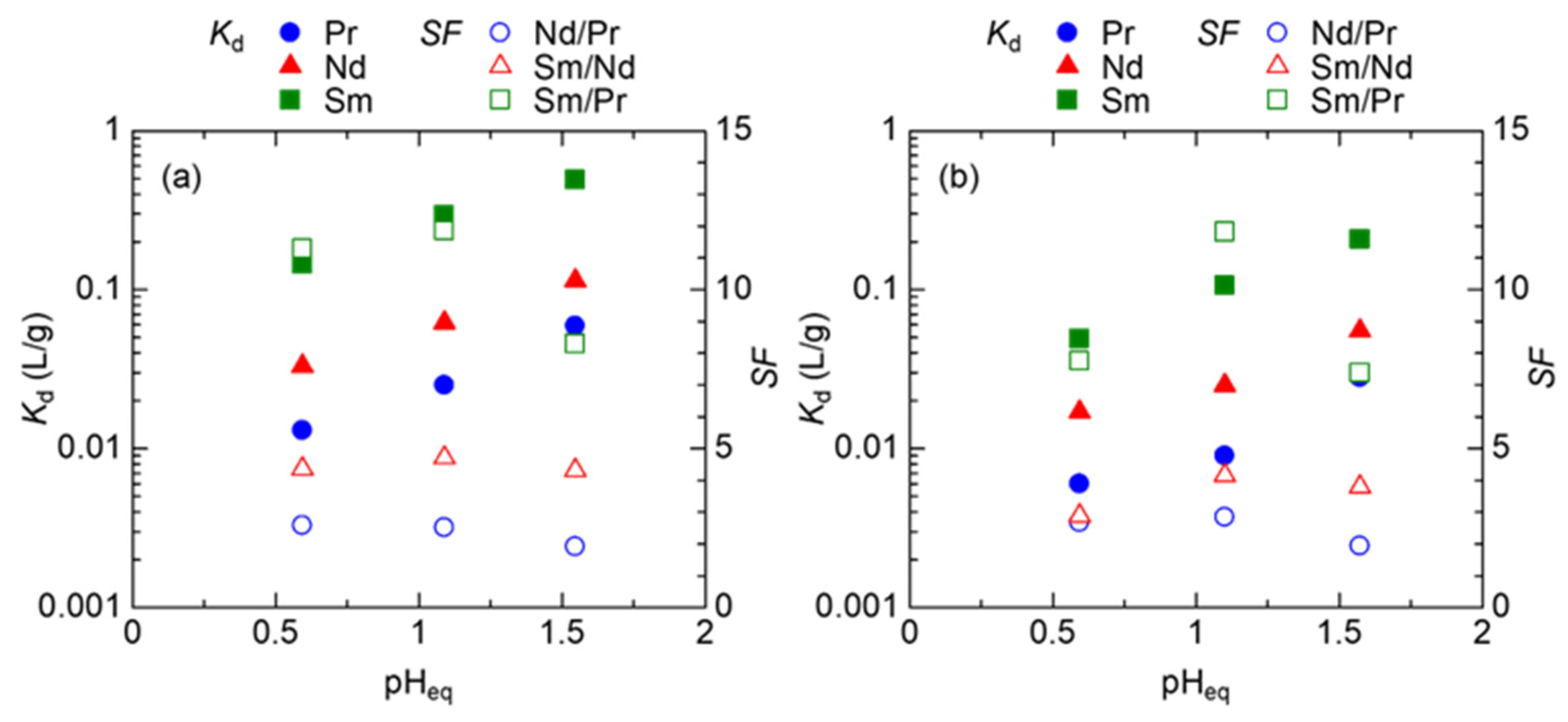

3.1. Batch Adsorption Tests of REEs

3.2. Column Tests with EDASiDGA

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morimoto, S.; Kuroki, H.; Narita, H.; Ishigaki, A. Scenario assessment of neodymium recycling in Japan based on substance flow analysis and future demand forecast. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 23, 2120–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Geng, Y.; Sarkis, J.; Xiao, S.; Gao, Z. Dynamic neodymium stocks and flows analysis in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, J.W., II; Vander Wal, R.L. NdFeB Permanent Magnet Uses, Projected Growth Rates and Nd Plus Dy Demands across End-Use Sectors through 2050: A Review. Minerals 2023, 13, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Kumari, A.; Panda, R.; Kumar, J.R.; Yoo, K.; Lee, J.Y. Review on hydrometallurgical recovery of rare earth metals. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 165, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C.K.; Krishnamurthy, N. Extractive Metallurgy of Rare Earths, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ouardi, Y.E.; Virolainen, S.; Mouele, E.S.M.; Laatikainen, M.; Repo, E.; Laatikainen, K. The recent progress of ion exchange for the separation of rare earths from secondary resources—A review. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 218, 106047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathapati, S.V.S.H.; Free, M.L.; Sarswat, P.K. A Comparative Study on Recent Developments for Individual Rare Earth Elements Separation. Processes 2023, 11, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salfate, G.; Sánchez, J. Rare Earth Elements Uptake by Synthetic Polymeric and Cellulose-Based Materials: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brião, G.V.; Silva, M.G.; Vieira, M.G.A. Adsorption potential for the concentration and recovery of rare earth metals from NdFeB magnet scrap in the hydrometallurgical route: A review in a circular economy approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danouche, M.; Bounaga, A.; Oulkhir, A.; Boulif, R.; Zeroual, Y.; Benhida, R.; Lyamlouli, K. Advances in bio/chemical approaches for sustainable recycling and recovery of rare earth elements from secondary resources. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, B.A.; Alam, M.S.; Flynn, S.L.; Chen, N.; Hao, W.; Shivakumar, K.R.; Swaren, L.; Rueda, D.G.; Konhauser, K.O.; Alessi, D.S.; et al. Rare Earth Element Adsorption to Clay Minerals: Mechanistic Insights and Implications for Recovery from Secondary Sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 7217–7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosen, J.; Spooren, J.; Binnemans, K. Adsorption performance of functionalized chitosan-silica hybrid materials toward rare earths. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 19415–19426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Xu, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, E.; Li, C. An ion imprinted macroporous chitosan membrane for efficiently selective adsorption of dysprosium. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 189, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihama, S.; Harano, T.; Yoshizuka, K. Silica-based solvent impregnated adsorbents for separation of rare earth metals. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshina, H.; Chen, J.; Amada, H.; Seko, N. Chain entanglement of 2-ethylhexyl hydrogen-2-ethylhexylphosphonate into methacrylate-grafted nonwoven fabrics for applications in separation and recovery of Dy(III) and Nd(III) from aqueous solution. Polymers 2020, 12, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T.; Narita, H.; Tanaka, M. Immobilization of diglycol amic acid on silica gel for selective recovery of rare earth elements. Chem. Lett. 2014, 43, 1414–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T.; Narita, H.; Tanaka, M. Adsorption behavior of rare earth elements on silica gel modified with diglycol amic acid. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 152, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki, T.; Ogata, T.; Kakinuma, R.; Narita, H.; Tokoro, C.; Tanaka, M. Preparation of polymeric adsorbents bearing diglycolamic acid ligands for rare earth elements. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 11424–11430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T.; Narita, H.; Tanaka, M. Rapid and selective recovery of heavy rare earths by using an adsorbent with diglycol amic acid group. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 155, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T.; Narita, H.; Tanaka, M. Adsorption mechanism of rare earth elements by adsorbents with diglycolamic acid ligands. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 163, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganawa, H.; Shimojo, K.; Mitamura, H.; Sugo, Y.; Noro, J.; Goto, M. A new “green” extractant of the diglycol amic acid type for lanthanides. Solvent Extr. Res. Dev. 2007, 14, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Shimojo, K.; Fujiwara, I.; Fujisawa, K.; Okamura, H.; Sugita, T.; Oshima, T.; Baba, Y.; Naganawa, H. Extraction behavior of rare-earth elements using a mono-alkylated diglycolamic acid extractant. Solvent Extr. Res. Dev. 2016, 23, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.C.; Loraas, J.A. Complexes of the rare earths. III. Mixed complexes with N-hydroxyethylethylenediaminetriacetic acid. Inorg. Chem. 1963, 2, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schijf, J.; Byrne, R.H. Speciation of yttrium and the rare earth elements in seawater: Review of a 20-year analytical journey. Chem. Geol. 2021, 584, 120479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritmon, T.F.; Goedken, M.P.; Choppin, G.R. The complexation of lanthanides by aminocarboxylate ligands—I. Stability constants. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1977, 39, 2021–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yokoi, S.; Katoh, M.; Minato, M.; Takizawa, N. Stability constants of rare-earth complexes with some organic ligands. In The Rare Earths in Modern Science and Technology; McCarthy, G.J., Rhyne, J.J., Silber, H.B., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

| pHeq | MeASiDGA | EDASiDGA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd/Pr | Sm/Nd | Sm/Pr | Nd/Pr | Sm/Nd | Sm/Pr | |

| 0.59 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 11 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 7.8 |

| 1.10 | 2.5 | 4.7 | 12 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 12 |

| 1.57 | 1.9 | 4.3 | 8.3 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 7.4 |

| log K1 | SF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pr | Nd | Sm | Nd/Pr | Sm/Nd | Sm/Pr | |

| IDA a | 3.84 | 4.07 | 4.57 | 1.70 | 3.16 | 5.37 |

| NTA b | 9.69 | 9.87 | 10.21 | 1.51 | 2.19 | 3.31 |

| HEDTA c | 14.17 | 14.47 | 14.85 | 2.00 | 2.40 | 4.79 |

| EDTA d | 16.14 | 16.31 | 16.76 | 1.48 | 2.82 | 4.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogata, T.; Narita, H. Separation of Adjacent Light Rare Earth Elements Using Silica Gel Modified with Diglycolamic Acid. Materials 2024, 17, 2648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112648

Ogata T, Narita H. Separation of Adjacent Light Rare Earth Elements Using Silica Gel Modified with Diglycolamic Acid. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112648

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgata, Takeshi, and Hirokazu Narita. 2024. "Separation of Adjacent Light Rare Earth Elements Using Silica Gel Modified with Diglycolamic Acid" Materials 17, no. 11: 2648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112648