Micro-Milling of Additively Manufactured Al-Si-Mg Aluminum Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

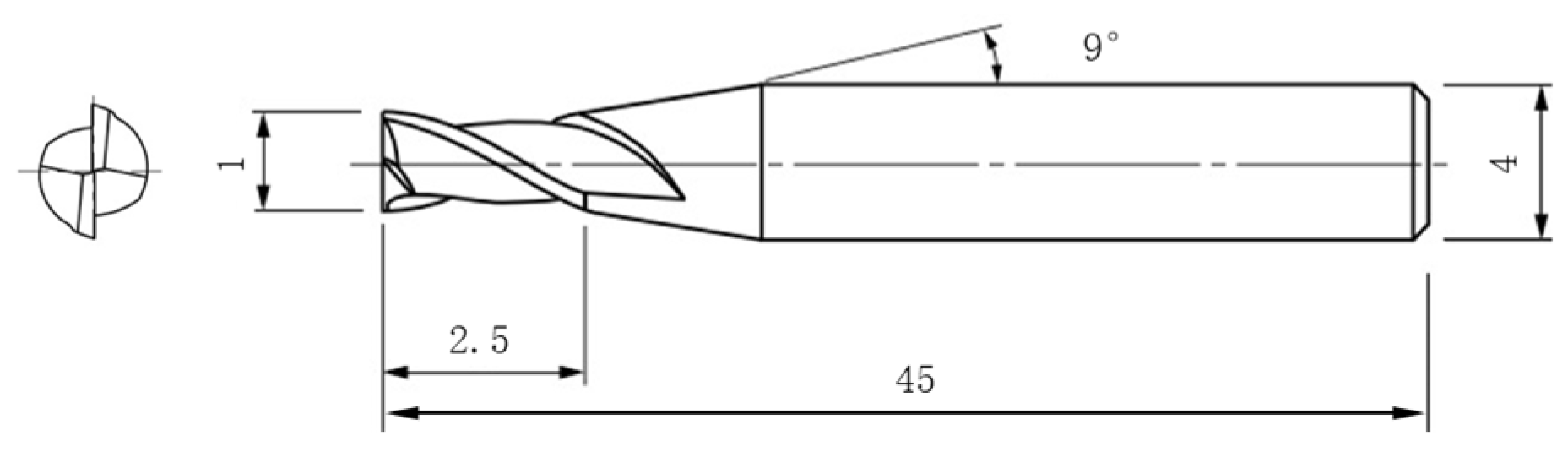

2. Experimental Procedures

3. Results and Discussions

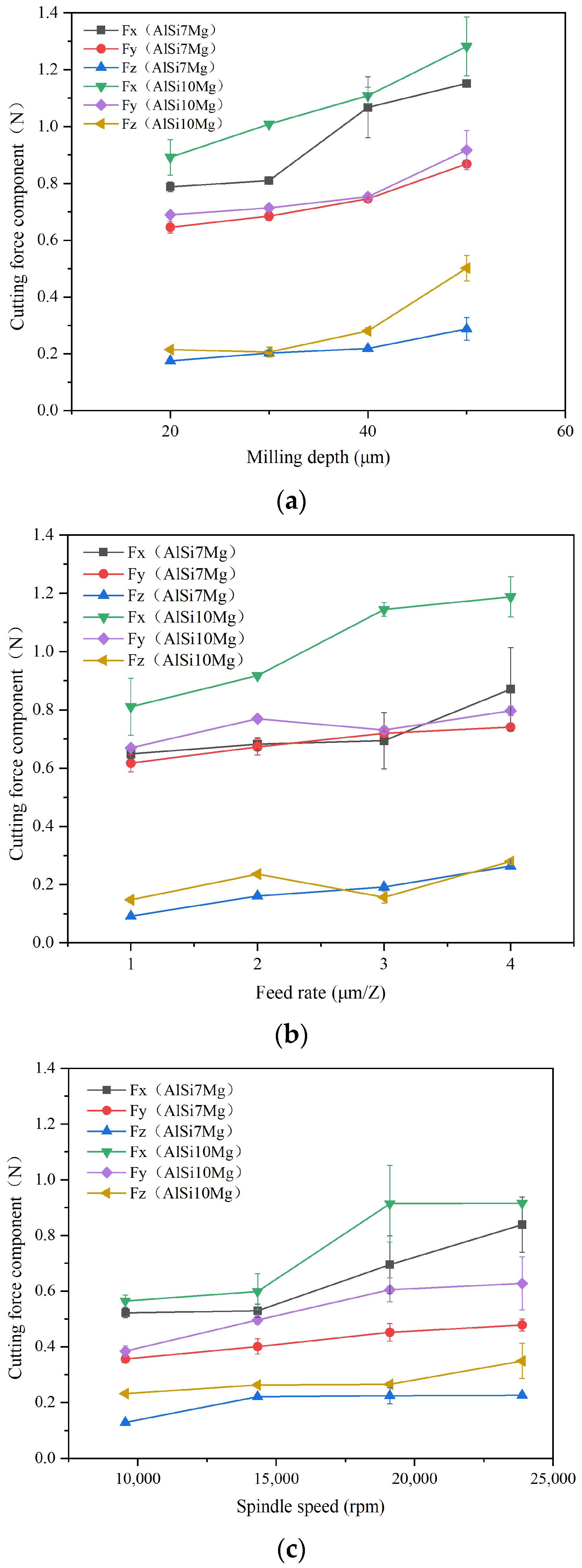

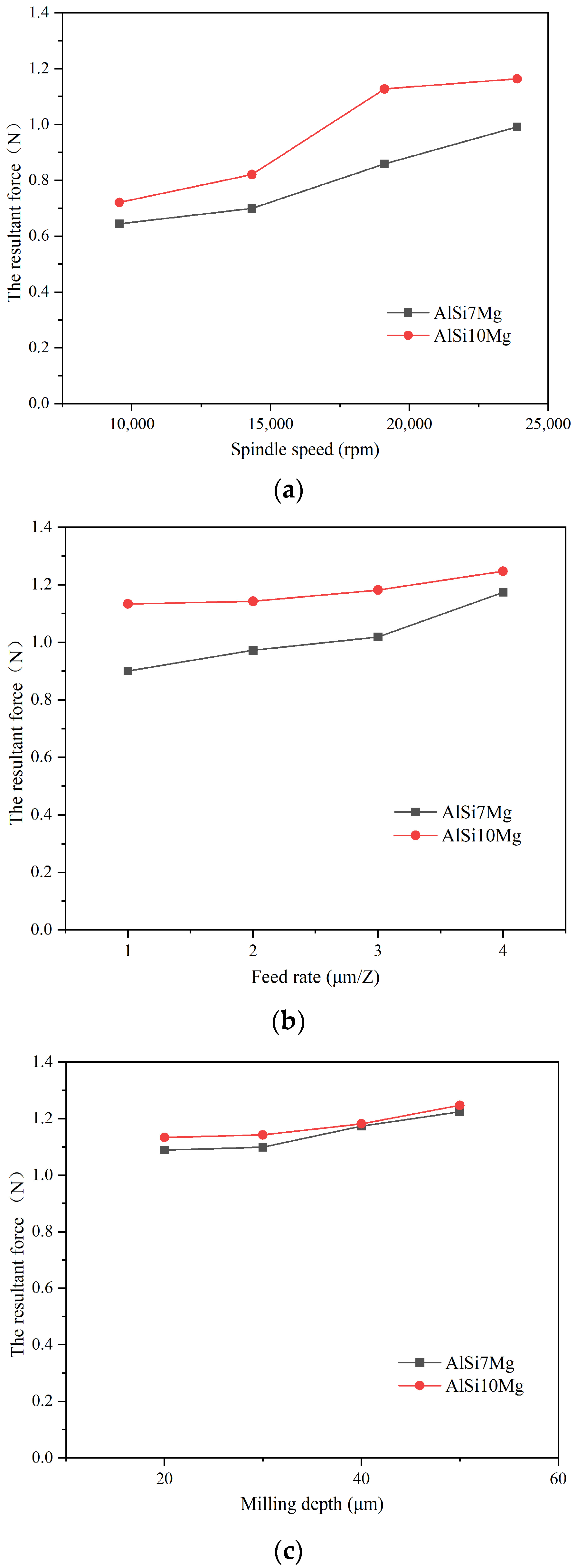

3.1. The Cutting Force Comparison

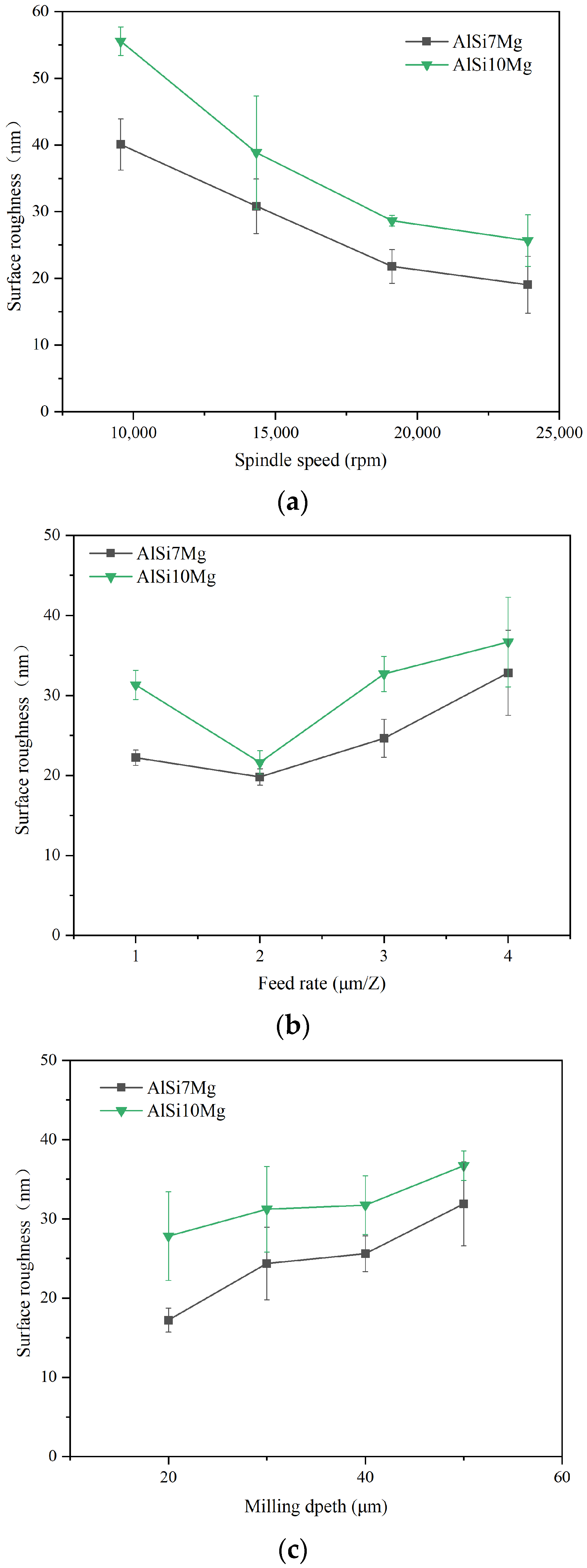

3.2. The Surface Roughness Comparison

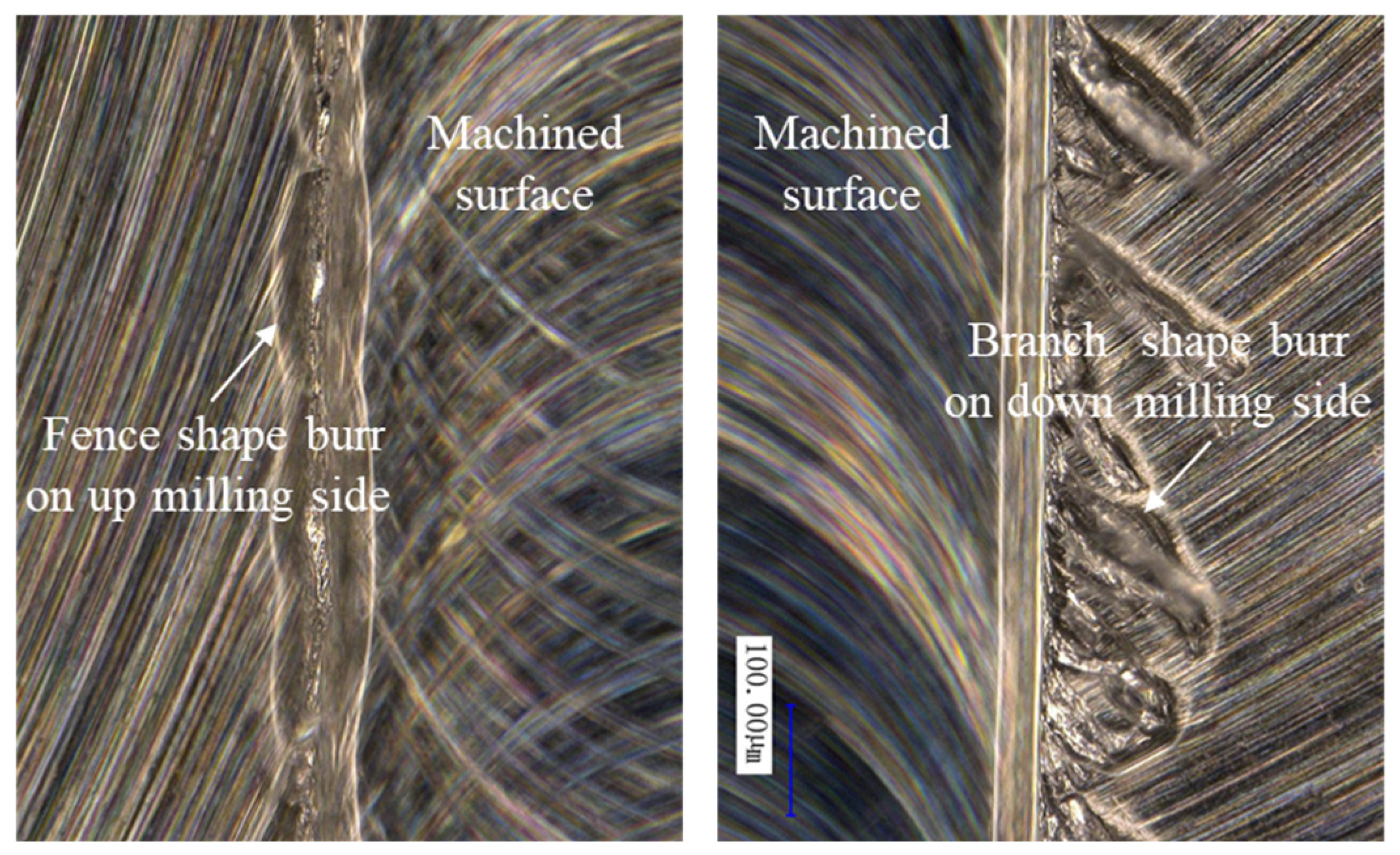

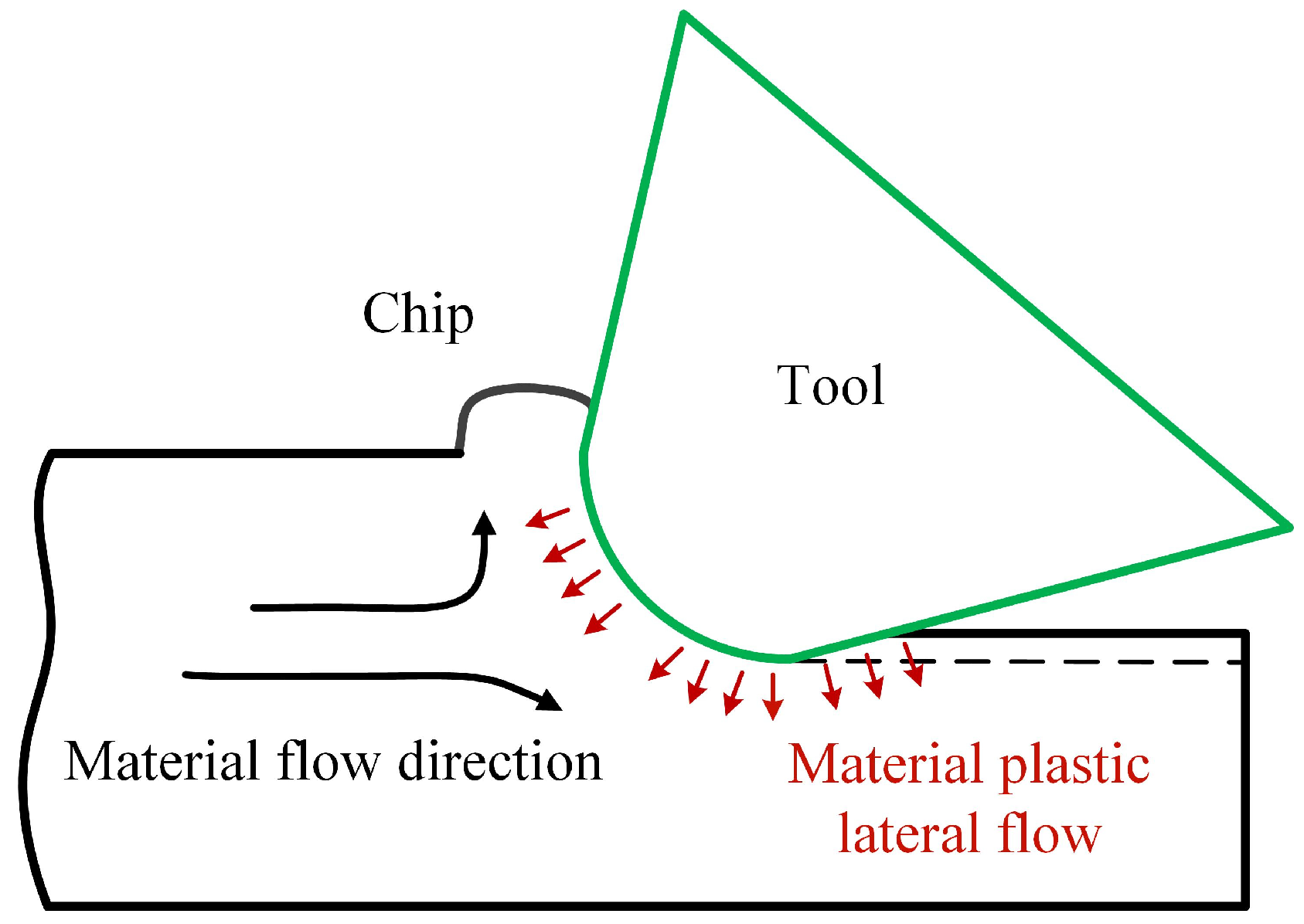

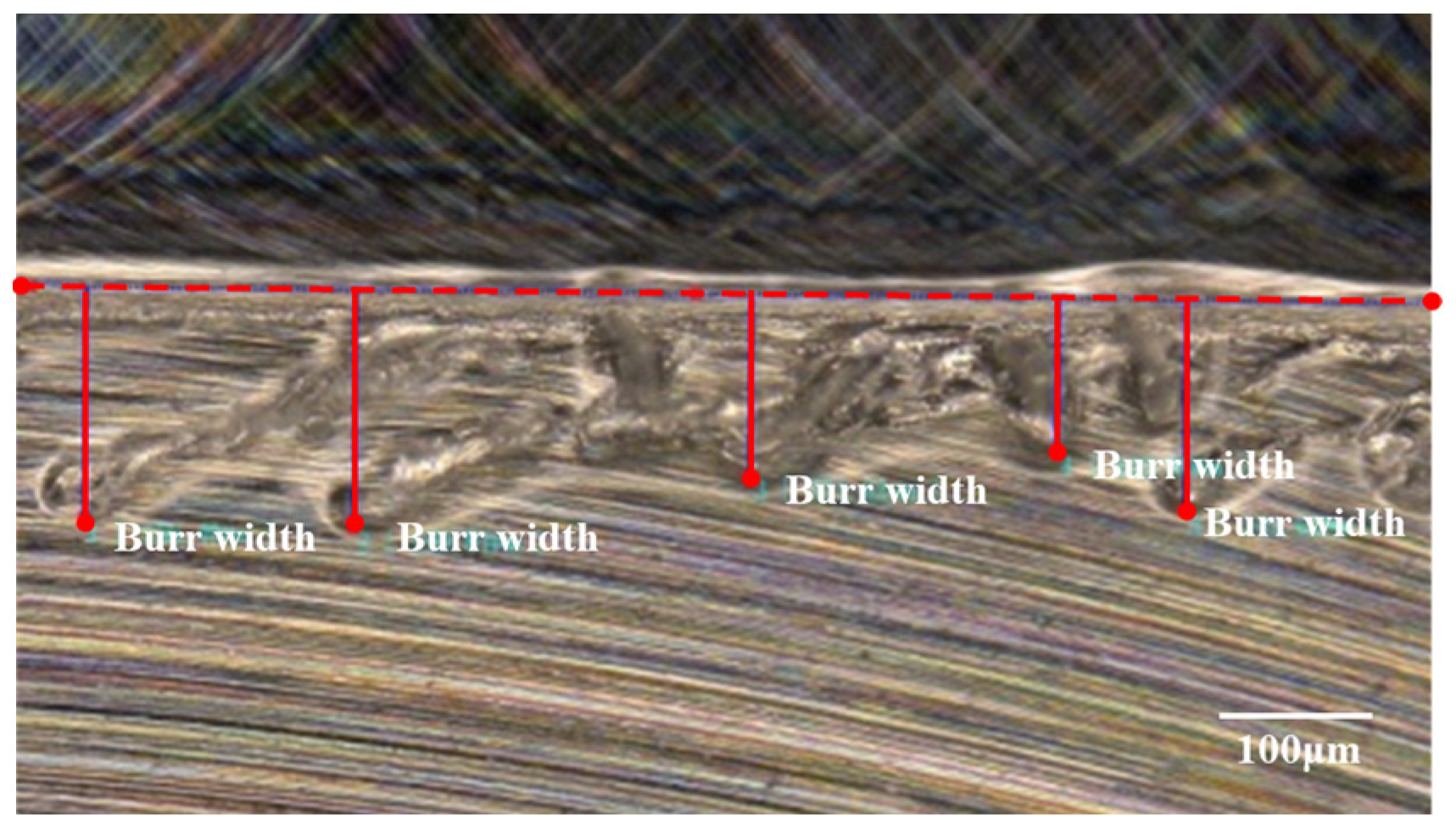

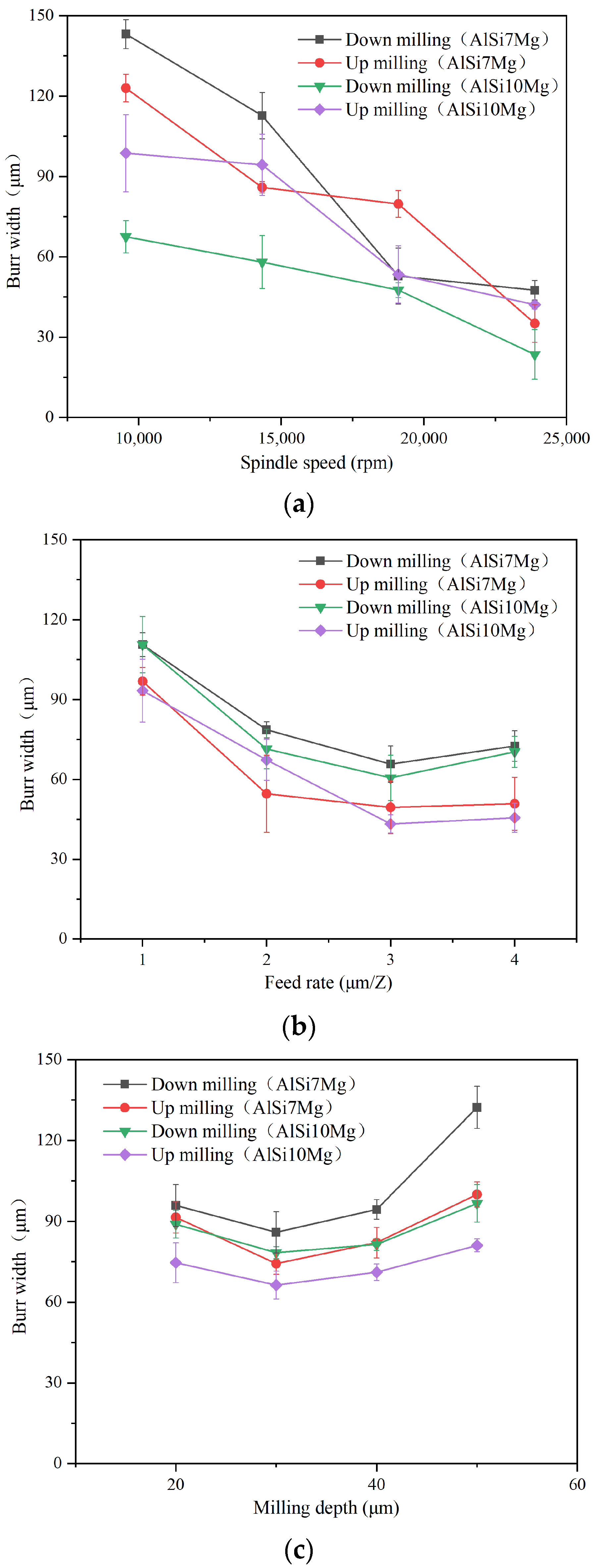

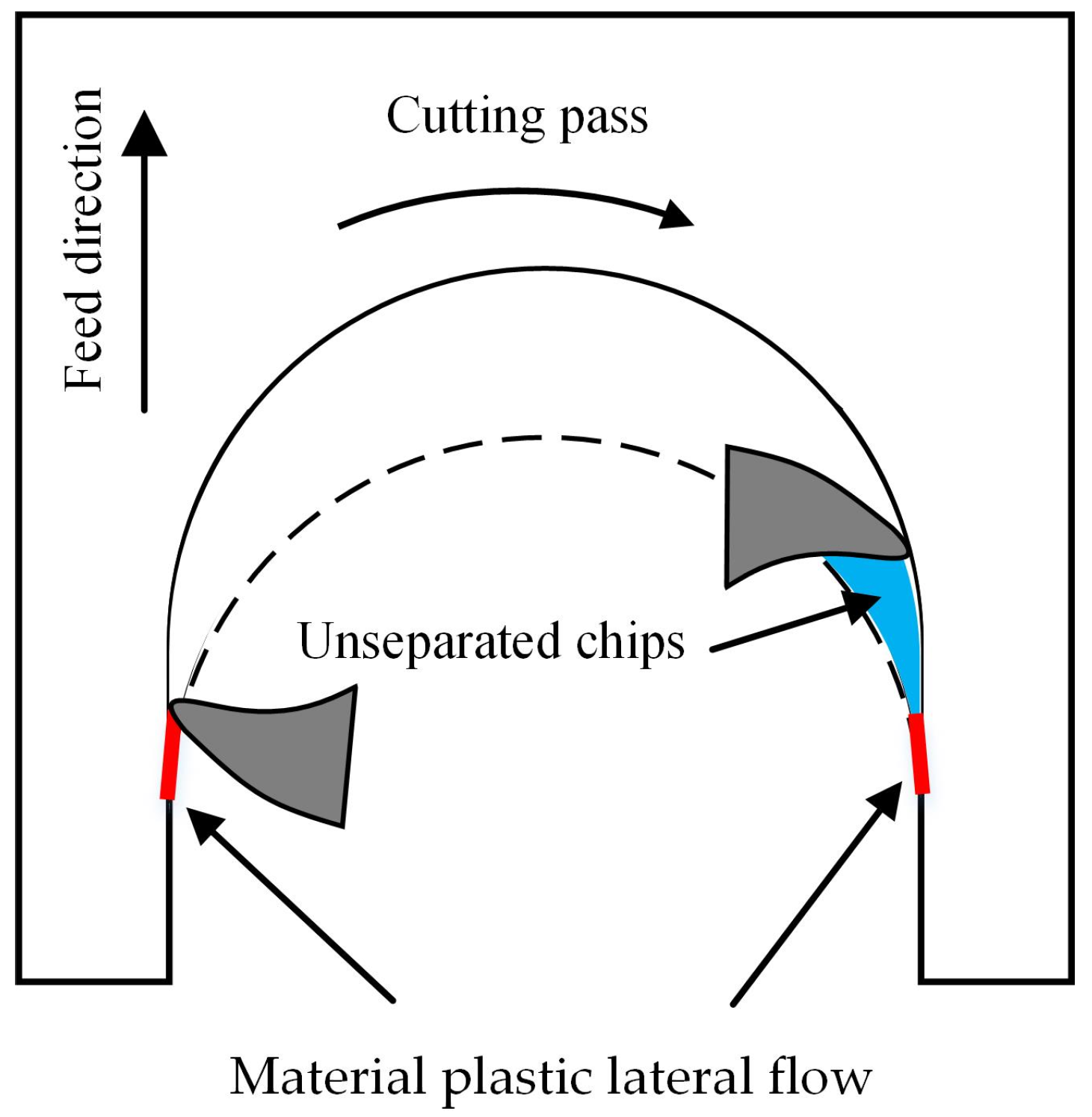

3.3. The Burr Formation Comparison

4. Conclusions

- The cutting force of the AlSi7Mg and AlSi10Mg alloys increases with the increase in cutting parameters. Because of the higher material hardness of AlSi10Mg, the cutting force component Fx is 21.9% higher, the feed force Fy is 10.4% higher, and the axial force Fz is 30.7% higher than AlSi7Mg, on average.

- Surface roughness in the micro-milling of AlSi7Mg and AlSi10Mg alloys decreases with rising spindle speed and increases with rising feed rate and milling depth. The increased Si content of the additively manufactured aluminum alloys increases surface roughness. The surface roughness of AlSi10Mg is, on average, 26.9% higher than that of AlSi7Mg.

- Burr morphology in the micro-milling of additively manufactured aluminum alloys can be divided into fence and branch shapes, and the burr width on the down-milling edge is greater than up milling edge. In terms of machining parameters, the burr width gradually decreases with increased spindle speed. Because of the minimum cutting thickness and size effect, the burr width first decreases and then slightly increases with the feed rate. As the milling depth increases, the burr width shows a gradual increasing trend. Due to the relatively better plasticity of the AlSi7Mg, the generated burr width during the machining process is 28.1% larger on the up-milling edge and 10.1% larger on the down-milling edge than that of the AlSi10Mg.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, S.S.; Yue, X.; Li, Q.Y.; Peng, H.L.; Dong, B.X.; Liu, T.S.; Yang, H.Y.; Fan, J.; Shu, S.L.; Qiu, F.; et al. Development and applications of aluminum alloys for aerospace industry. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 944–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguang, Y.; Wang, W.J.; He, A.R.; Ma, W.J.; Tian, H.L. Lightweight design for the aluminum alloy-carbon fiber hybrid structure of the EMU car body. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 6441–6452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rometsch, P.A.; Zhu, Y.M.; Wu, X.H.; Huang, A.H. Review of high-strength aluminium alloys for additive manufacturing by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Des. 2022, 219, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Ye, J.L.; Song, B.; Li, R.D.; Shi, Y.S. Comparative study on microstructure and electrochemical corrosion resistance of Al7075 alloy prepared by laser additive manufacturing and forging technology. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzengue, A.G.B.; Mpofu, K.; Mathe, N.; Daniyan, I.; Muvunzi, R. An experimental investigation of selective laser process parameters on aluminium alloy (AlSi12). Procedia CIRP 2023, 118, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotadia, H.R.; Gibbons, G.; Das, A.; Howes, P.D. A review of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing of aluminium alloys: Microstructure and properties. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, G.; Lin, X.; Zhu, D.; Jiang, J.; Shi, S.; Liu, F.; Huang, W.; Vanmeensel, K. Development of a high strength Zr/Sc/Hf-modified Al-Mn-Mg alloy using Laser Powder Bed Fusion: Design of a heterogeneous microstructure incorporating synergistic multiple strengthening mechanisms. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 57, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wu, D.; Ge, C.; Lu, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Niu, F.; Ma, G.; Luo, K.; et al. Superior strength of laser-arc hybrid additive manufactured Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy enabled by a tunable microstructure. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 68, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.Q.; Guo, W.; Li, J.S.; Xu, S.B.; Li, H.X.; Liu, P. A review of laser additive manufacturing (LAM) aluminum alloys: Methods, microstructures and mechanical properties. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.G.; Hu, Z.H.; Seet, H.L.; Liu, T.T.; Liao, W.H.; Ramamurty, U.; Nai, S.M.L. Recent progress on the additive manufacturing of aluminum alloys and aluminum matrix composites: Microstructure, properties, and applications. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2023, 190, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Chen, H.; Xiong, J. Research progress in laser additive manufacturing of aluminum alloys: Microstructure, defect, and properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakizadi, A.; Mallipeddi, D.; Dadbakhsh, S.; M'Saoubi, R.; Krajnik, P. Post-processing of additively manufactured metallic alloys—A review. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2022, 179, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizzul, L.; Sorgato, M.; Bertolini, R.; Ghiotti, A.; Bruschi, S. Influence of additive manufacturing-induced anisotropy on tool wear in end milling of Ti6Al4V. Tribol. Int. 2020, 146, 106200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, O.; Kazi, A.; Lin, T.; Zvanut, R.; Tai, B. Single point machining of A205 aluminum: A comparison of cast and additively manufactured materials. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 110, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, C.A.; Bassani p Fiocchi, J.; Giuranno, D.; Novakovic, R.; Tuissi, A.; Ricci, E. Investigation of high temperature behavior of AlSi10Mg produced by selective laser melting. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 259, 123975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Wu, H.; Li, X.D.; Yin, J.; Wang, X.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, B.B.; Guo, X.P.; Yang, G. Effects of annealing on periodic microstructure and mechanical properties of inter-layer hammering hybrid wire arc additively manufactured aluminum alloy. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 49, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimbäck, D.; Kaserer, L.; Mair, P.; Mohebbi, M.S.; Staron, P.; Maier-Kiener, V.; Letofsky-Papst, I.; Kremmer, T. Advancements in metal additive manufacturing: In-situ heat treatment of aluminium alloys during the laser powder bed fusion process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 14, 146102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, Z.; Ke, W.; Jiang, F.; Zhao, M.; Li, L.; Shen, J.; Zhu, L. Investigation on surface quality in micro milling of additive manufactured Ti6Al4V titanium alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 101, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segebade, E.; Gerstenmeyer, M.; Dietrich, S.; Zanger, F.; Schulze, V. Influence of anisotropy of additively manufactured AlSi10Mg parts on chip formation during orthogonal cutting. Procedia CIRP 2019, 82, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.K.; Zhao, X.S.; Liu, Q.; Guo, X.M.; Lin, F.T.; Yang, L.Q.; Sun, T. Investigation of Surface Integrity of Selective Laser Melting Additively Manufactured AlSi10Mg Alloy under Ultrasonic Elliptical Vibration-Assisted Ultra-Precision Cutting. Materials 2022, 15, 8910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chandra, S.; Rashid, R.A.; Palanisamy, S.; Ding, S. Machinability of additively manufactured titanium alloys: A comprehensive review. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 75, 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.W.; Wu, X.; He, L.J.; Jiang, F.; Shen, J.Y.; Zhu, L.F. Comparative study on micro-milling machinability of titanium alloys prepared by different processes: Forging process, additive manufacturing process and heat-treatment process. Precis. Eng. 2024, 88, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.E.F.; Amaral, A.; Couto, A.; Coelho, J.; Reis, A.; Rosa, P.A.R. Comparison of the machinability of the 316L and 18Ni300 additively manufactured steels based on turning tests. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L-J. Mater. -Des. Appl. 2021, 235, 2207–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, Q.; Kong, S.; Kang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ni, J. Study on the structure and properties of the AlSi10Mg samples produced by 3D printing. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 27, 16–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zou, T.; Chen, M.; Zhu, H.; Mei, S. Effect of Heat Treatments on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AlSi7Mg Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Si wt% | Mg wt% | Fe wt% | Zn wt% | Ti wt% | Ni wt% | Al wt% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlSi7Mg | 7 | 0.36 | 0.1 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.004 | Bal |

| AlSi10Mg | 10 | 0.36 | 0.1 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.004 | Bal |

| Material | Yield Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) | Hardness (HV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlSi7Mg | 299 | 14.3 | 110.5 |

| AlSi10Mg | 280 | 8.1 | 120.7 |

| Parameter Name and Unit | Value |

|---|---|

| Spindle speed n/rpm | 9554, 14,331, 19,108, 23,885 |

| Feed rate fz μm/Z | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Milling depth ap μm | 20, 30, 40, 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Q.; Kang, X.; Wu, X. Micro-Milling of Additively Manufactured Al-Si-Mg Aluminum Alloys. Materials 2024, 17, 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112668

He Q, Kang X, Wu X. Micro-Milling of Additively Manufactured Al-Si-Mg Aluminum Alloys. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112668

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Qiongyi, Xiaochong Kang, and Xian Wu. 2024. "Micro-Milling of Additively Manufactured Al-Si-Mg Aluminum Alloys" Materials 17, no. 11: 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112668

APA StyleHe, Q., Kang, X., & Wu, X. (2024). Micro-Milling of Additively Manufactured Al-Si-Mg Aluminum Alloys. Materials, 17(11), 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112668