Effects of Hydrogen Plasma Treatment on the Electrical Behavior of Solution-Processed ZnO Thin Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

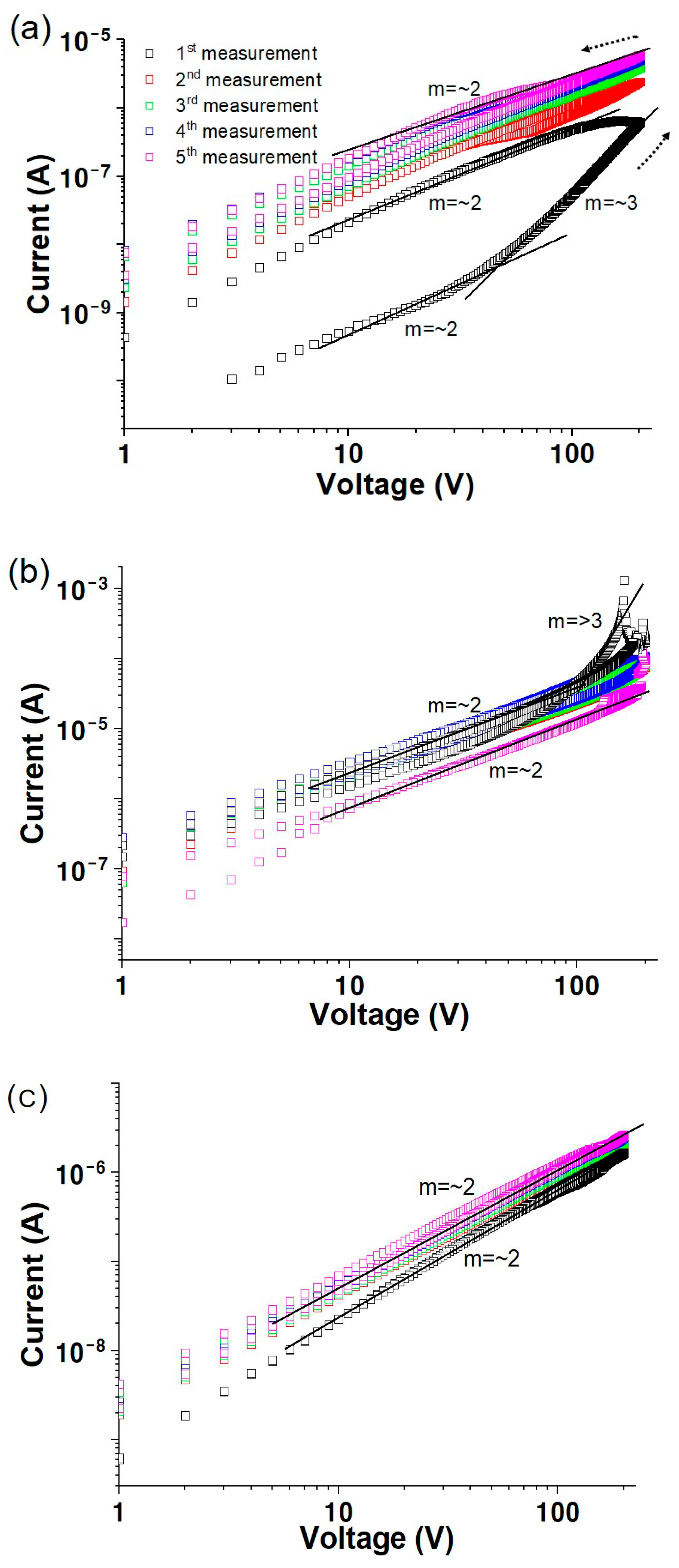

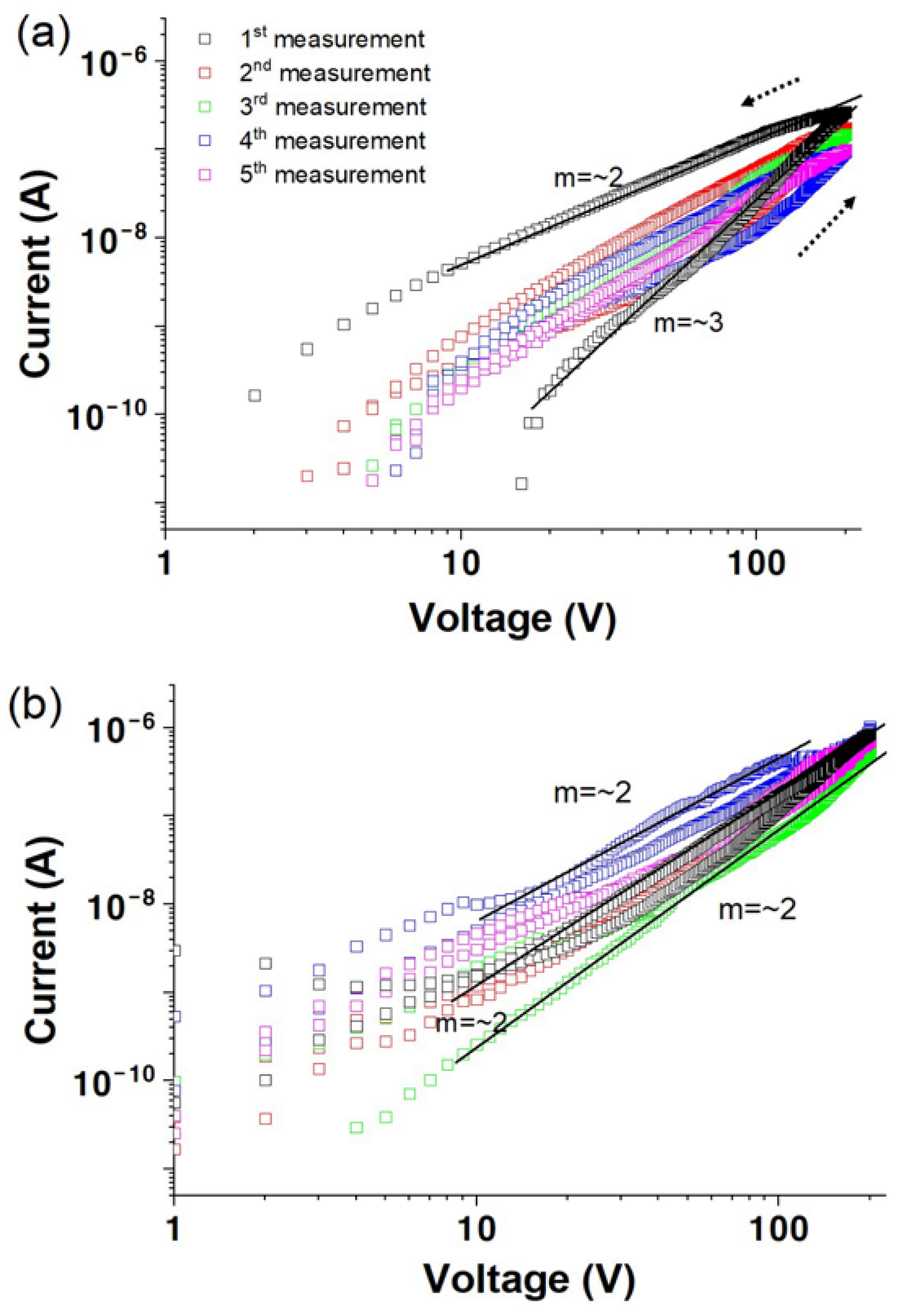

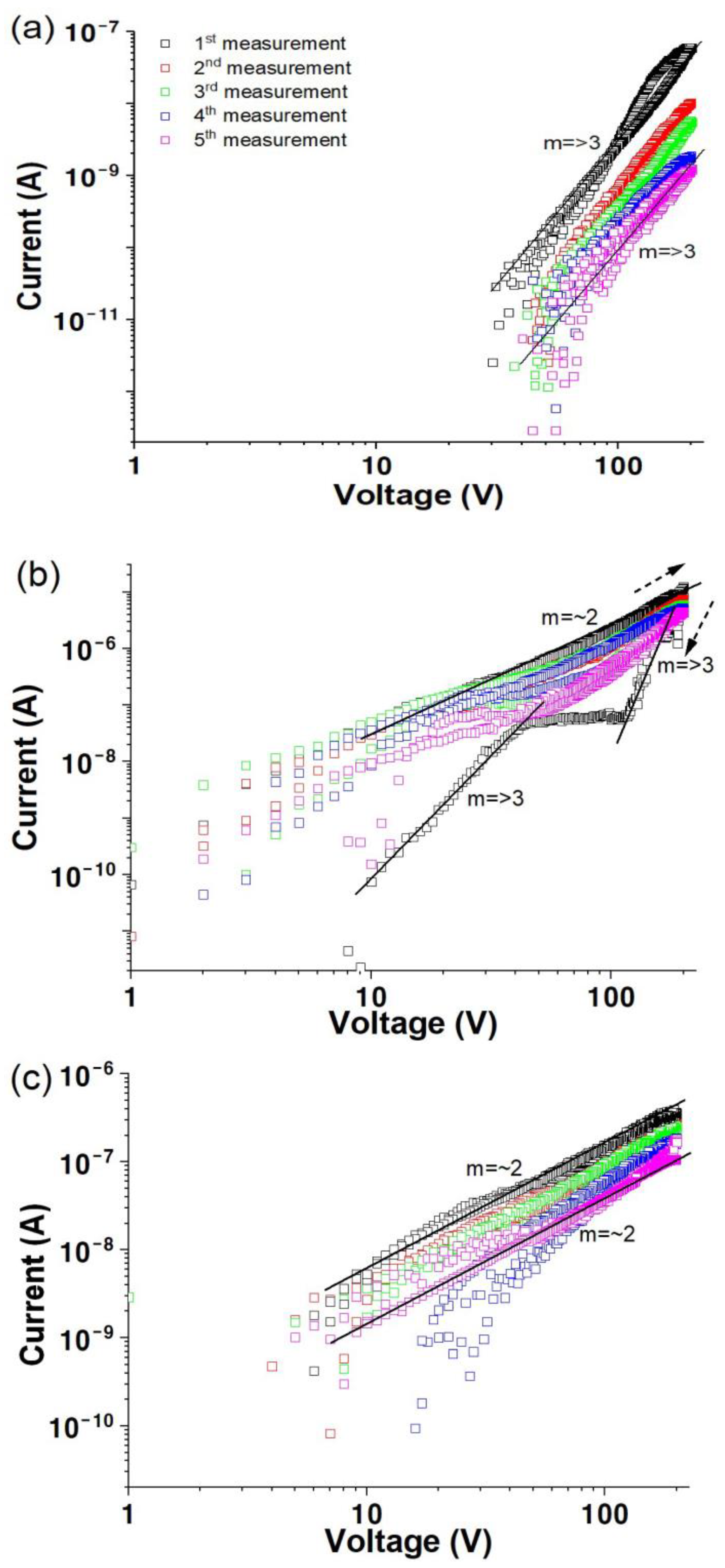

3.1. Vacuum Environment

3.2. Air Environment

3.3. Oxygen Environment

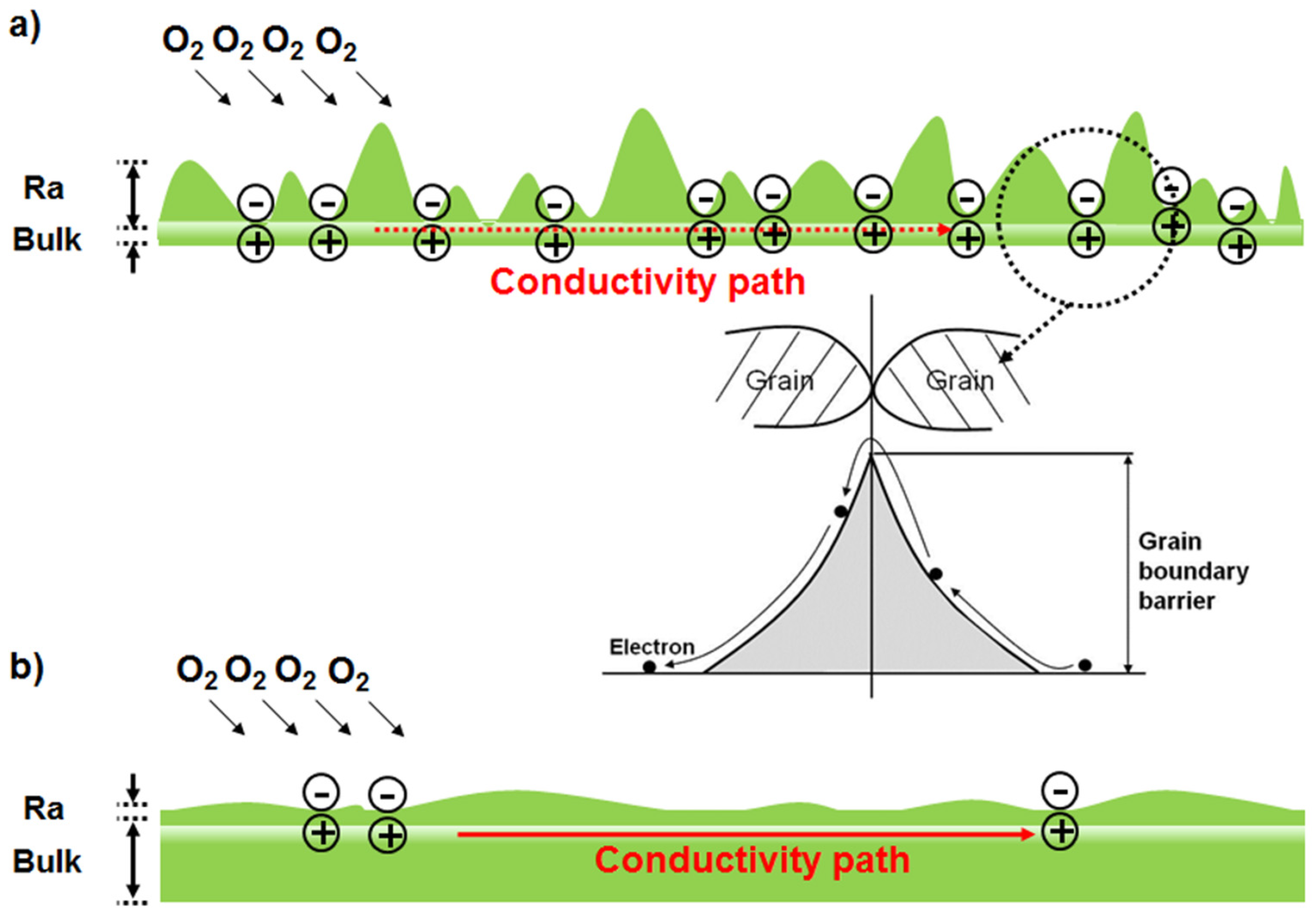

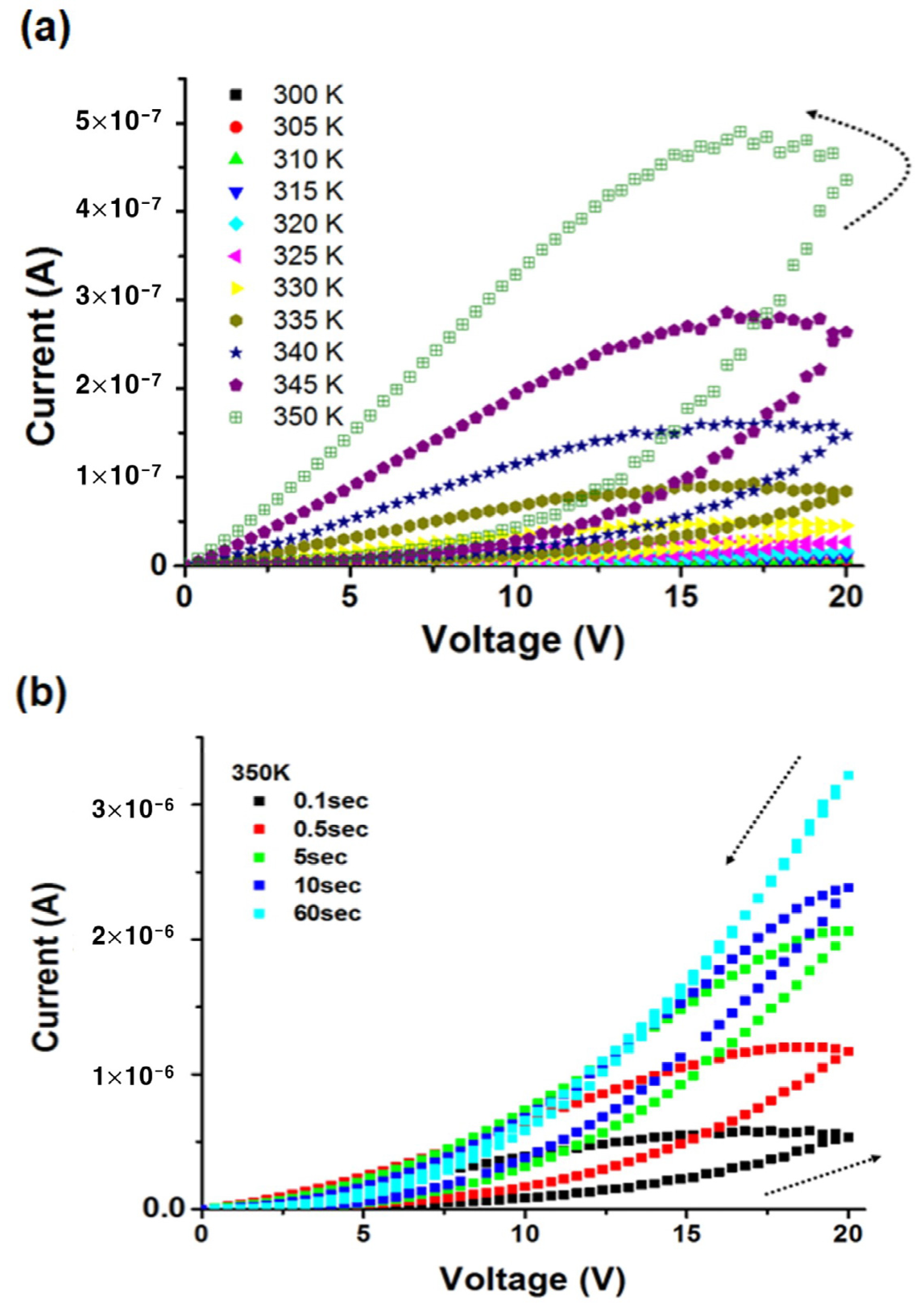

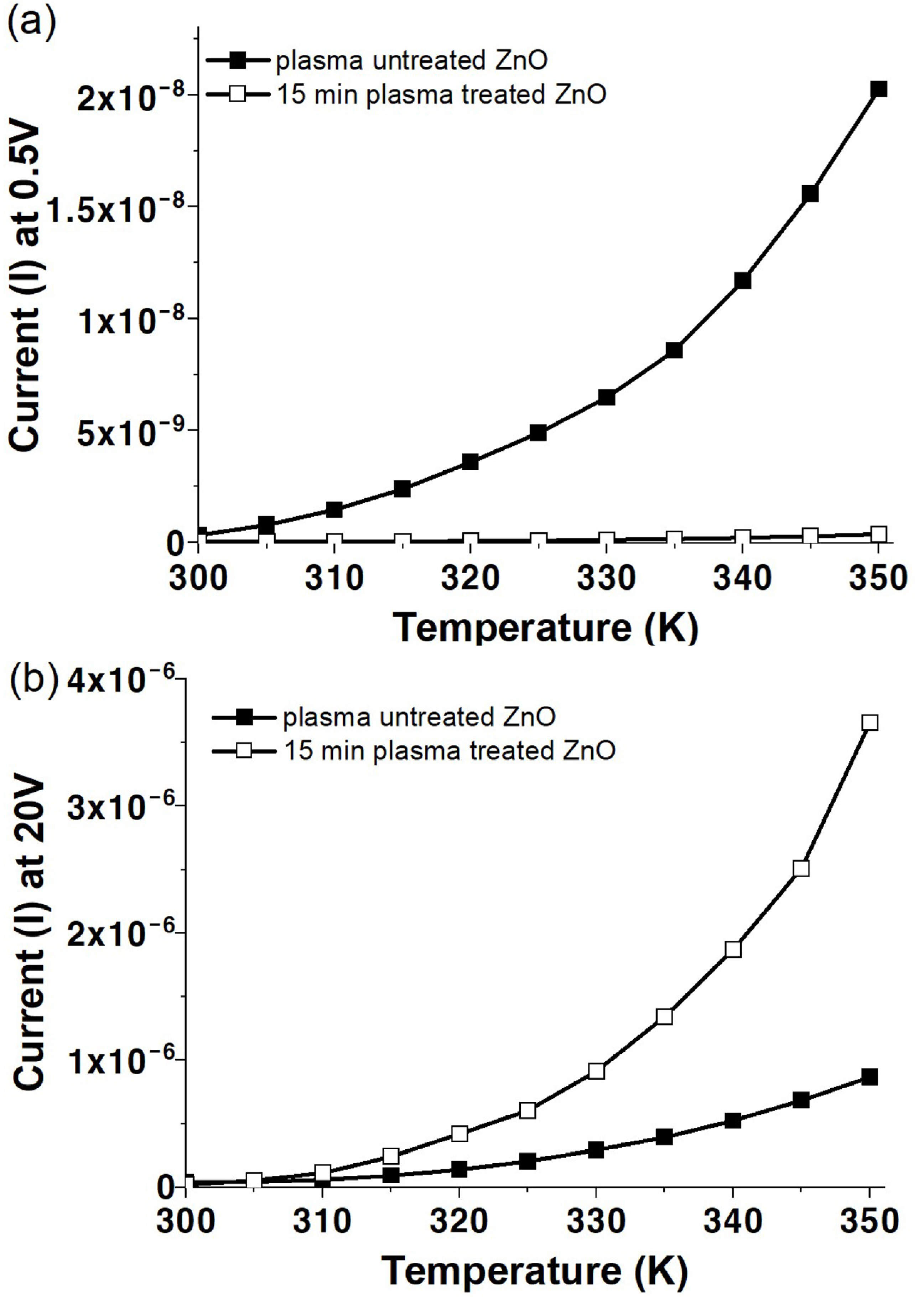

3.4. Electrical Transport Characteristics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prete, P.; Lovergine, N.; Tapfer, L. Nanostructure size evolution during Au-catalysed growth by carbo-thermal evaporation of well-aligned ZnO nanowires on (100) Si. Appl. Phys. A 2007, 88, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-W.; Fujita, S.; Park, H.-K.; Yang, B.; Kim, H.-K.; Yoon, D.H. Growth of ZnO nanostructures in a chemical vapor deposition process. J. Cryst. Growth 2006, 292, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Shi, L.; Li, X. Effect of TiO2 buffer layer on the structural and optical properties of ZnO thin films deposited by E-beam evaporation and sol–gel method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 255, 3230–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-K.; Meen, T.-H.; Wu, T.-C.; Lai, Y.-D.; He, Y.-K. Morphology and optical properties of ZnO microrods grown by high-temperature hydrothermal method. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 148, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, S.A.; Chan, K.-Y.; Yow, H.-K.; Sahdan, M.Z.; Saim, H.; Knipp, D. Zinc oxide films prepared by sol-gel spin coating technique. Appl. Phys. A 2010, 104, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Bhatti, K.A.; Qindeel, R.; Alonizan, N.; Althobaiti, H.S. Characterizations of multilayer ZnO thin films deposited by sol-gel spin coating technique. Results Phys. 2017, 7, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.K.; Yang, J.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Mo, Y.-G.; Kim, H.D. Origin of threshold voltage instability in indium-gallium-zinc oxide thin film transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 123508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Valle, F.D.; Simonnet, I.; Yamada, I.; Delaunay, J.-J. Competitive surface effects of oxygen and water on UV photoresponse of ZnO nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 023110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, M.A.; Schilling, R.B. Current Injection in Solids. Semicond. Semimet. 1970, 6, 1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, B.; Abaab, M.; Rezig, B. Structural and electrical properties of ZnO films prepared by screen printing technique. Thin Solid Films 2001, 383, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.C.; Chaudhri, A.K. Sol-Gel Derived Cu-Doped ZnO Thin Films for Optoelectronic Applicaions. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 21877–21881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yergaliuly, G.; Soltabayev, B.; Kalybekkyzy, S.; Bakenov, Z.; Mentbayeva, A. Effect of thickness and reaction media on properties of ZnO thin films by SILAR. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, R.L.; Wager, J.F.; Jayaraj, M.K.; Tate, J. Electrical characterization of transparent p–i–n heterojunction diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 90, 5763–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-W.; Retamal, J.R.D.; Chen, C.-Y.; He, J.-H. Photocarrier Relaxation Behavior of a Single ZnO Nanowire UV Photodetector: Effect of Surface Band Bending. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2012, 33, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.H.; Gao, T.; Wnag, Y.G.; Wang, T.H. Adsorption and desorption of oxygen probed from ZnO nanowire films by photocurrent measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 123117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, M.D.; Jokela, S.J.; Zhuravlev, K.K.; Simpson, P.J.; Lynn, K.G. Infrared spectroscopy of hydrogen in ZnO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 81, 3807–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.J.; Zhang, X.W.; You, J.B.; Cai, P.F.; Yin, Z.G.; An, Q.; Ma, X.B.; Jin, P.; Wang, Z.G.; Chu, P.K. Effects of hydrogen plasma treatment on the electrical and optical properties of ZnO films: Identification of hydrogen donors in ZnO. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 1780–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Nicolay, S.; Steinhauser, J.; Kroll, U.; Ballif, C. Relaxing the conductivity/transparency trade-off in MOCVD ZnO thin films by hydrogen plasma. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 5177–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.L.; Wang, J.; Zhu, S.J.; Wu, J.; Wu, R.; Zeng, D.W.; Xie, C.S. Influence of hydrogen introduction on structure and properties of ZnO thin films during sputtering and post-annealing. Thin Solid Films 2011, 519, 3809–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herklotz, F.; Hupfer, A.; Johansen, K.M.; Svensson, B.G.; Koch, S.G.; Lavrov, E. Infrared absorption on a complex comprising three equivalent hydrogen atoms in ZnO. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 155203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macco, B.; Knoops, C.M.; Verheijen, M.A.; Beyer, W.; Greatore, M.; Kessels, W.M.M. Atomic layer deposition of high-mobility hydrogen-doped zinc oxide. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 173, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Patelli, A.; Ghamgosar, P.; Cesca, T.; Enrichi, F.; Mattei, G.; Vomiero, A. Tuning ZnO nanorods photoluminescence through atmospheric plasma treatments. APL Mater. 2019, 7, 081111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Pearson, C.; Kim, H.-G.; Park, M.-Y.; Kim, H.; Do, L.-M.; Petty, M.C. Optimization of a Solution-Processed SiO2 Gate Insulator by Plasma Treatment for Zinc Oxide Thin Film Transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.; Pearson, C.; Kim, H.-G.; Park, M.-Y.; Kim, H.; Do, L.-M.; Petty, M.C. Solution-processed SiO2 gate insulator formed at low temperature for zinc oxide thin-film transistors. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 36083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Pearson, C.; Lee, H.U.; Ahn, K.; Cho, C.-R.; Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Do, L.-M.; Petty, M.C. Effects of hydrogen plasma treatment on the electrical behavior of solution-processed ZnO transistors. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 074509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Pearson, C.; Lee, Y.U.; Winchester, L.; Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Do, L.-M.; Petty, M.C. Zinc Oxide Thin-Film Transistors Fabricated at Low Temperature by Chemical Spray Pyrolysis. J. Electron. Mater. 2014, 43, 4241–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, K.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, Y.U.; Pearson, C.; Petty, M.C.; Kim, H. UV-Assisted Low Temperature Oxide Dielectric Films for TFT Applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 1, 1400206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Lee, H.U.; Pearson, C.; Petty, M.C. Short Channel Effect of Solution-Processed ZnO Thin Film Transistors: Optimization for Photolithographic Process. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2018, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschwald, W.H. Zinc Oxide: An Outstanding Example of a Binary Compound Semiconductor. Accounts Chem. Res. 1985, 18, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, B.; Blakesley, J.C.; Greenham, N.C. Solution-Processed Ultraviolet Photodetectors Based on Colloidal ZnO Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 1649–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbakel, F.; Meskers, S.C.J.; Janssen, R.A.J. Electronic memory effects in diodes from a zinc oxide nanoparticle-polystyrene hybrid material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, B.; Gao, F.; Greenham, N.C. Memristive devices based on solution-processed ZnO nanocrystals. Phys. Status Solidi A 2010, 207, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Lim, H.; Kim, C.; Song, I.; Park, J.; Park, Y.; Chung, J. Amorphous gallium indium zinc oxide thin film transistors: Sensitive to oxygen molecules. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 192101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Dai, F.; Fan, D.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhuang, Z.; Pi, K.; Mo, J.; Deng, J. Synthesis and Optical Properties of Solid and Hollow ZnO Microspheres Prepared by Hydrothermal Method. Mater. Sci. 2018, 24, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, H.; Ye, L.; Xu, J. The role of solution-processed hifg-k gate dielectrics in electrical performance of oxide thin-film transistors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 5389–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Desai, A.; Salleo, A.; Jimison, L.A. Solution-Processable Zirconium Oxide Gate Dielectrics for Flexible Organic Field Effect Transistors Operated at Low Voltages. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 2571–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Acton, O.; Hutchins, D.O.; Cernetic, N.; Jen, A.K.-Y. Multifunctional phosphonic acid self-assembled monolayers on metal oxides as dielectrics, interface modification layers and semiconductors for low-voltage high-performance organic field-effect transistors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 14110–14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Kiesel, P.; VandeWalle, C.G.; Johnson, N.M.; Nause, J.; Dohler, G.H. Effects of an Electrically Conducting Layer at the Zinc Oxide Surface. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 44, 7271–7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, H.; Wagiran, R.; Hamidon, M.N. Humidity Sensors Principle, Mechanism, and Fabrication Technologies: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2014, 14, 7881–7939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.-F.; Chang, T.-C.; Li, H.-W.; Chen, C.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, S.-C.; Tseng, T.-Y.; Tai, Y.-H. Influence of H2O Dipole on Subthreshold Swing of Amorphous Indium–Gallium–Zinc-Oxide Thin Film Transistors. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2010, 14, H114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Jeong, J.K.; Chung, H.-J.; Mo, Y.-G.; Kim, H.D. Electronic transport properties of amorphous indium-gallium-zinc oxide semiconductor upon exposure to water. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 072104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K.; Hahn, D. Electron Spin Resonance of Lattice Defects in Zinc Oxide. Status Solidi A 1974, 24, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janotti, A.; Van de Walle, C.G. Fundamentals of zinc oxide as a semiconductor. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2009, 72, 126501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakani, N.; Jee, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Oh, J.Y.; Yoon, Y.S. Thickness dependency of sol-gel derived ZnO thin films on gas sensing behaviors. Thin Solid Films 2019, 519, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Xu, K.; Wang, P.; Li, X. Surface roughness and resistivity of Au film on Si-(111) substrate. Microelectron. Eng. 2009, 66, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaliauskiene, G.; Kazukauskas, V.; Rinkevicius, V.; Storasta, J.; Vaitkus, J.V.; Bates, R.; OShea, V.; Smith, K.M. Thermally stimulated currents in semi-insulating GaAs Schottky diodes and their simulation. Appl. Phys. A 1999, 69, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.G.; Taylor, G.W. High-Field Isothermal Currents and Thermally Stimulated Currents in Insulators Having Discrete Trapping Levels. Phys. Rev. B 1972, 5, 1619–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auret, F.D.; Goodman, S.A.; Hayes, M.; Legodi, M.J.; van Laarhoven, H.A.; Look, D.C. Electrical characterization of 1.8 MeV proton-bombarded ZnO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 79, 3074–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, C.D.; Kang, S.H.; Kim, I.W.; Lee, J.S.; Chung, G.S. Influence of Sintering Temperature on Conduction Behaviors for CoO- and ZnO- Doped SnO2 Varistor Ceramics. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2006, 49, 2423–2427. [Google Scholar]

| 0.5 V | 20 V | |

|---|---|---|

| Solution-processed ZnO | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 0.67 ± 0.01 |

| 15 min plasma-treated ZnO | 0.71 ± 0.10 | 0.84 ± 0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.-I.; Lee, H.U.; Pearson, C.; Petty, M.C.; Jeong, Y. Effects of Hydrogen Plasma Treatment on the Electrical Behavior of Solution-Processed ZnO Thin Films. Materials 2024, 17, 2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112673

Park J-I, Lee HU, Pearson C, Petty MC, Jeong Y. Effects of Hydrogen Plasma Treatment on the Electrical Behavior of Solution-Processed ZnO Thin Films. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112673

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Ji-In, Hyun Uk Lee, Christopher Pearson, Michael C. Petty, and Yesul Jeong. 2024. "Effects of Hydrogen Plasma Treatment on the Electrical Behavior of Solution-Processed ZnO Thin Films" Materials 17, no. 11: 2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112673

APA StylePark, J.-I., Lee, H. U., Pearson, C., Petty, M. C., & Jeong, Y. (2024). Effects of Hydrogen Plasma Treatment on the Electrical Behavior of Solution-Processed ZnO Thin Films. Materials, 17(11), 2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112673