Removal Efficiency of Bottom Ash and Sand Mixtures as Filter Layers for Fine Particulate Matter

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

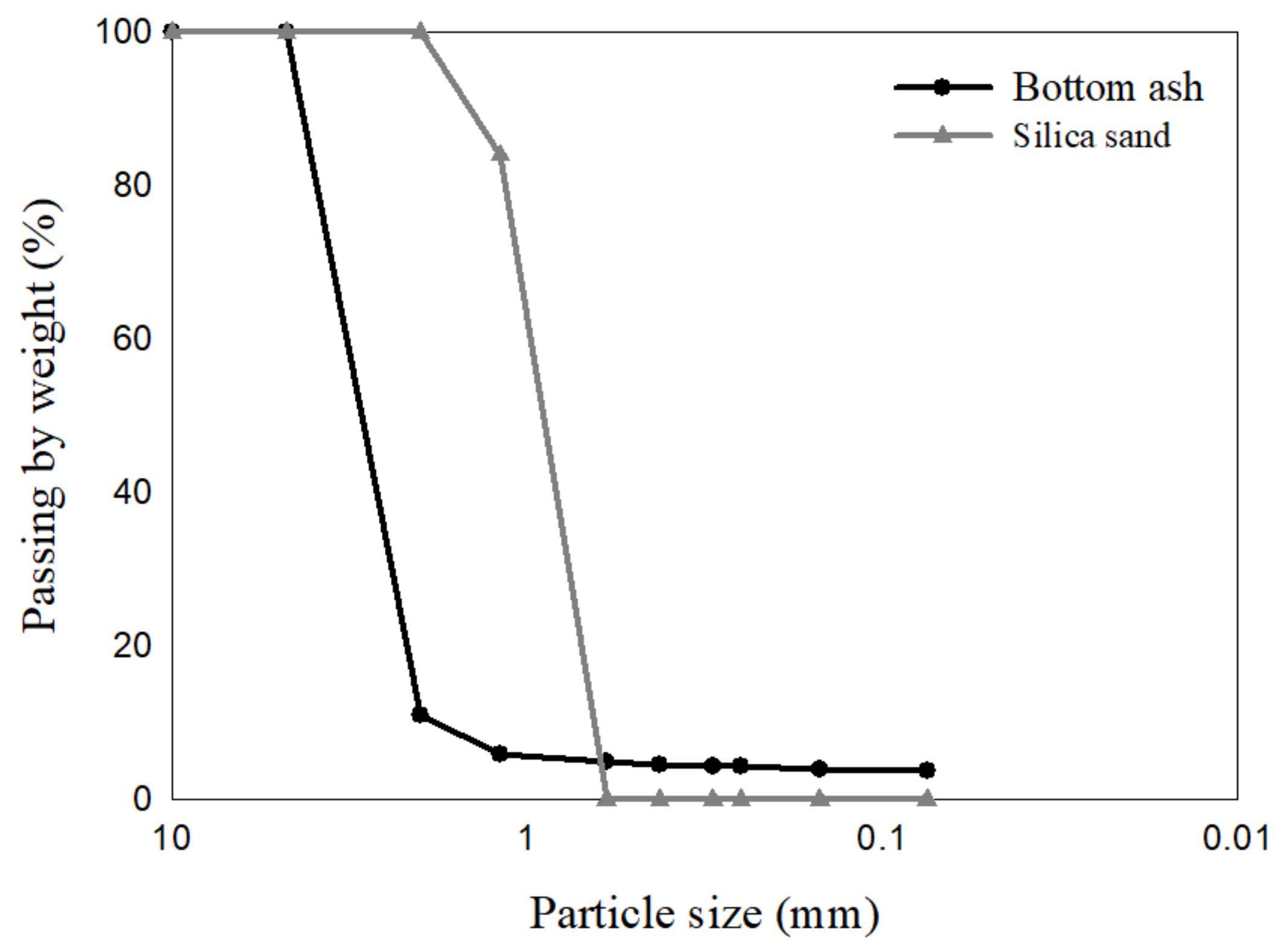

2.1. Filter Materials

2.2. Unit Weight of Filter Materials

2.3. Permeability Coefficient

2.4. Removal Efficiency for 60 μm Particles

2.5. Removal Efficiency for 1.8 μm, 10 μm, and 60 μm Particles

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Permeability Coefficient

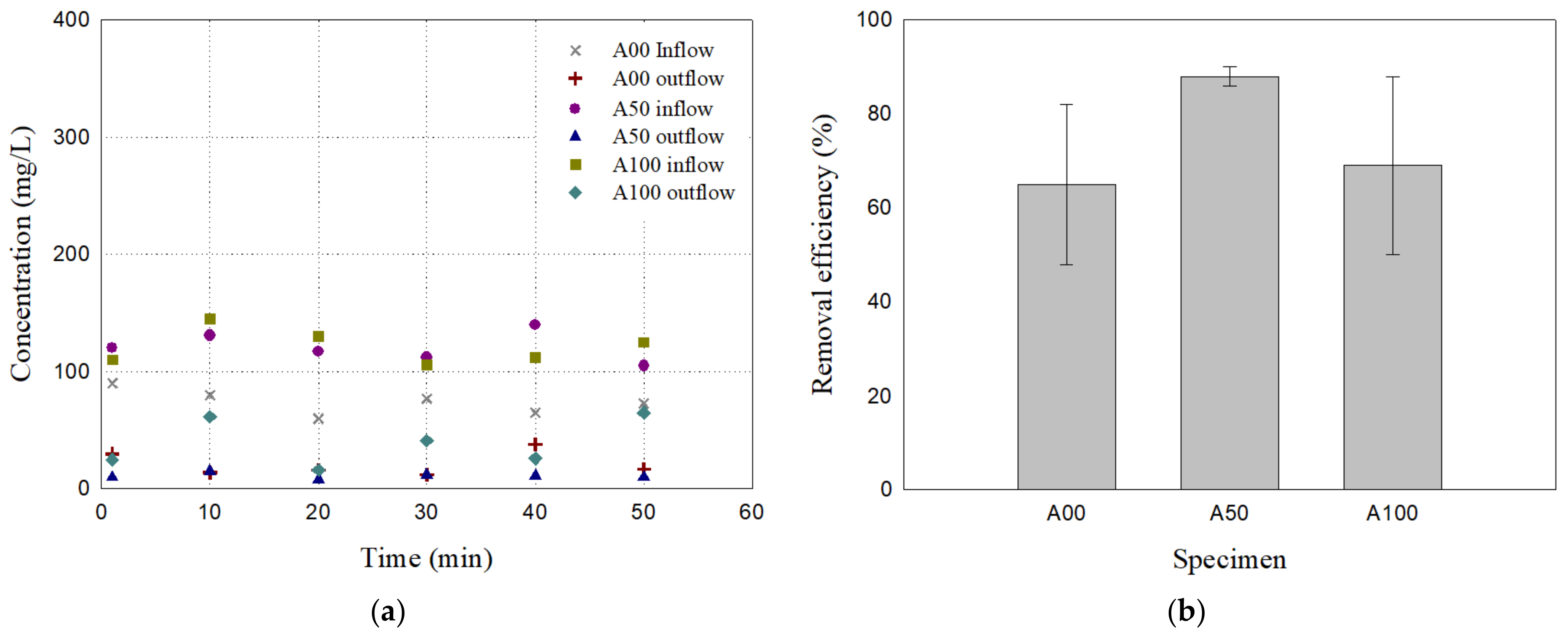

3.2. Particulate Matter Removal Efficiency (PM60)

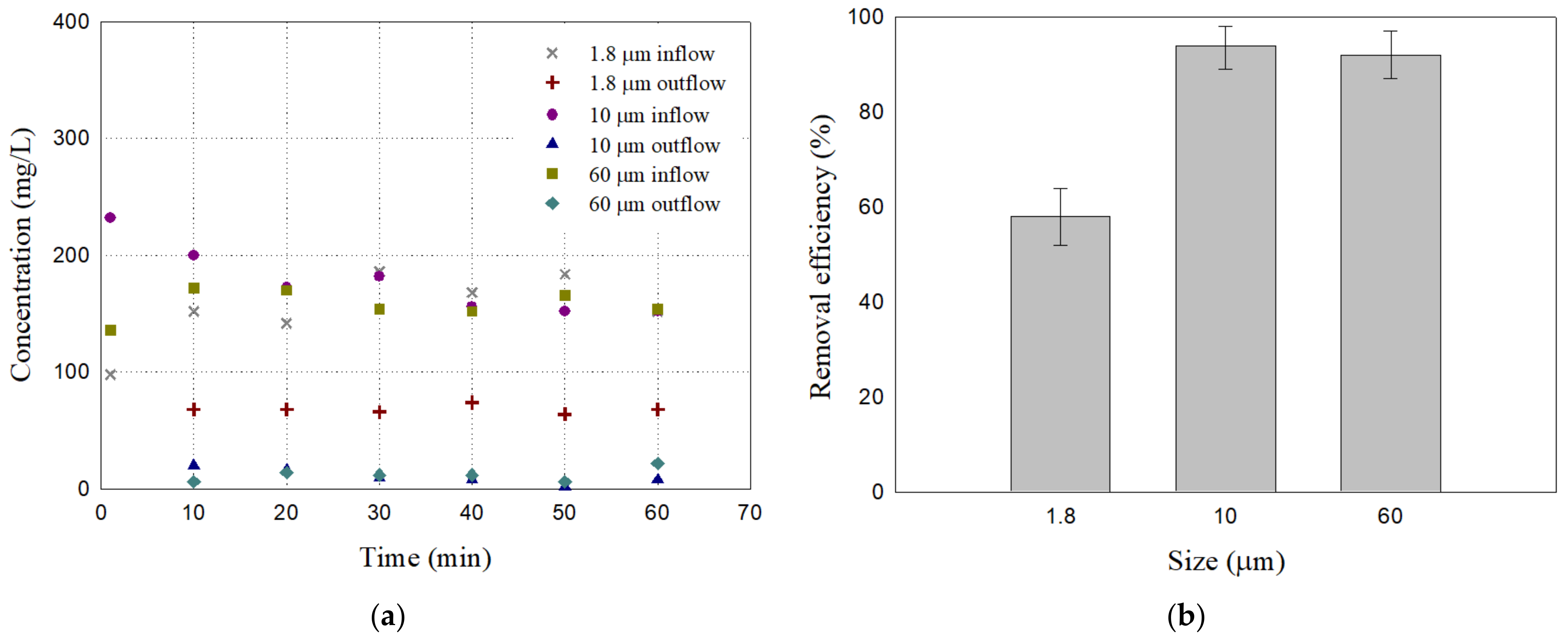

3.3. Particulate Matter Removal Efficiency (PM10 and PM2.5)

4. Conclusions

- Permeability coefficients: Among A00, A100, and A50, which are compacted for the same duration by vibration, resulting in different unit weights, the mixed filter (A50) had a lower permeability coefficient than the uniform filters (A00 and A100). Among A30, A50, and A70, which are designed to have the same unit weight, the one with higher bottom ash content (A70) tended to have a lower permeability coefficient than the others.

- Particle removal efficiency for 60 μm particulates: Among the uniform filters (A00 and A100) and the mixed filter (A50), A50 showed a higher removal efficiency of 89.06% compared to 70.45% and 68.92% for A00 and A100, respectively. The other mixed filters, A30 and A70, showed a removal efficiency of 87.30% and 87.60%, respectively, which were comparable to that of A50. The mixed filters exhibited more consistent and stable removal efficiency over time compared to the uniform filters.

- Particle removal efficiency of A50 filters for different particles: A50 had removal efficiencies of 58.05%, 93.92%, and 92.45% for 1.8 μm, 10 μm, and 60 μm particles, respectively. These findings highlight the potential of bottom ash–sand mixtures as effective filter media even for PM10 road dust. The removal efficiency for 1.8 μm was not as good, but the A50 filter still screens out a considerable amount of the particles smaller than PM2.5. Further research may be required for the removal of finer particulate matter.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brattebo, B.O.; Booth, D.B. Long-term stormwater quantity and quality performance of permeable pavement systems. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4369–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.R. Permeable Interlocking Concrete Pavements, 4th ed.; Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute: Herndon, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, L.; Di Mascio, P.; Fusco, C. Porous Concrete for Pedestrian Pavements. Water 2019, 11, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Grabowiecki, P. Review of permeable pavement systems. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3830–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.N.; Hamouda, M.A.; El-Hassan, H.; Hinge, G. Permeable Pavement Systems for Effective Management of Stormwater Quantity and Quality: A Bibliometric Analysis and Highlights of Recent Advancements. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, B.T. Low-impact parking lot design reduces runoff and pollutant loads. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2001, 127, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassman, E.A.; Blackbourn, S. Permeable pavement performance over 3 years of monitoring. In Low Impact Development 2010: Redefining Water in the City; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2010; pp. 152–165. [Google Scholar]

- Siriwardene, N.R.; Deletic, A.; Fletcher, T.D. Clogging of stormwater gravel infiltration systems and filters: Insights from a laboratory study. Water Res 2007, 41, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, K.A.; Hunt, W.F.; Hathaway, J.M. Hydrologic Comparison of Four Types of Permeable Pavement and Standard Asphalt in Eastern North Carolina. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2008, 13, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. Characterization of coarse, fine, and ultrafine particles generated from the interaction between the tire and the road pavement. J. Korean Soc. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 29, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, A.; Gharibi, A.; Swietlicki, E.; Gudmundsson, A.; Bohgard, M.; Ljungman, A.; Blomqvist, G.; Gustafsson, M. Traffic-generated emissions of ultrafine particles from pavement–tire interface. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Yin, J.; Mark, D.; Stedman, J.; Appleby, R.S.; Booker, J.; Moorcroft, S. Studies of the coarse particle (2.5–10 μm) component in UK urban atmospheres. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 3667–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenschow, P.; Abraham, H.J.; Kutzner, K.; Lutz, M.; Preuß, J.D.; Reichenbächer, W. Some ideas about the sources of PM10. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, S23–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Ruiz, C.R.; Artiñano, B.; Hansson, H.C.; Harrison, R.M.; Buringh, E.; ten Brink, H.M.; Lutz, M.; Bruckmann, P.; et al. Speciation and origin of PM10 and PM2.5 in selected European cities. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 6547–6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Jones, A.M.; Gietl, J.; Yin, J.; Green, D.C. Estimation of the Contributions of Brake Dust, Tire Wear, and Resuspension to Nonexhaust Traffic Particles Derived from Atmospheric Measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 6523–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangeli, C.; Palermi, S.; Bianco, S.; Aruffo, E.; Chiacchiaretta, P.; Di Carlo, P. The relationship between pm2. 5 and pm10 in central italy: Application of machine learning model to segregate anthropogenic from natural sources. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhao, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X. Spatio-temporal variations of the PM2. 5/PM10 ratios and its application to air pollution type classification in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 692440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.-F.; Xu, Y.-H.; Shi, M.-H.; Lian, Y.-X. The impact of PM2. 5 on the human respiratory system. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sosa, B.S.; Porta, A.; Lerner, J.E.C.; Noriega, R.B.; Massolo, L. Human health risk due to variations in PM10-PM2. 5 and associated PAHs levels. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 160, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.E.; Abustan, I. An Investigation of Particle Size Distribution during Storm Events from an Urban Catchment. In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Urban Stormwater Management 1995: Integrated Management of Urban Environments; Preprints of Papers; Institution of Engineers: Barton, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Drapper, D.; Tomlinson, R.; Williams, P. Pollutant concentrations in road runoff: Southeast Queensland case study. J. Environ. Eng. 2000, 126, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Kim, J.; Ahn, J. TSS Removal Efficiency and Permeability Degradation of Sand Filters in Permeable Pavement. Materials 2023, 16, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segismundo, E.Q.; Lee, B.-S.; Kim, L.-H.; Koo, B.-H. Evaluation of the impact of filter media depth on filtration performance and clogging formation of a stormwater sand filter. J. Korean Soc. Water Environ. 2016, 32, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, J.-W.; Kim, T.-H.; Park, J.-S.; An, B. Effect of TSS Removal from Stormwater by Mixed Media Column on T-N, T-P, and Organic Material Removal. Water 2018, 10, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Haba, E.; Benito-Kaesbach, A.; Hernández-Crespo, C.; Sanz-Lazaro, C.; Martín, M.; Andrés-Doménech, I. Removal and fate of microplastics in permeable pavements: An experimental layer-by-layer analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korea Land and Housing Corporation and Korea Energy. A Study of Practical Application of Bottom Ash as Fill Materials and Road Materials. 2018. Available online: https://www.codil.or.kr/filebank/original/RK/OTKCRK190194/OTKCRK190194.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Tae-Hyeob, S.; Ha-Seog, K. A Evaluation of Physical and Chemical Properties for the Use of Embankment and Subgrade Materials of Bottom Ash Produced by Dry Process. J. Korea Concr. Inst. 2019, 31, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C136; Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Ahn, J.; Jalmasco, M.; Shin, H.-S.; Jung, J. Test Equipment and Procedure to Evaluate Permeability Characteristics of Permeable Pavements. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2017, 17, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA. Framework for Developing Suspended and Bedded Sediment (Sabs) Water Quality Criteria; EPA/822-R-06-001; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2006.

- The Ministry of Environment. A Manual for Non-Point Pollution Reduction Facility Installation, Management and Operation; The Ministry of Environment: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2016.

- ASTM D5907; Standard Test Methods for Filterable Matter (Total Dissolved Solids) and Nonfilterable Matter (Total Suspended Solids) in Water. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Won, J.; Kim, T.; Kang, M.; Choe, Y.; Choi, H. Kaolinite and illite colloid transport in saturated porous media. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 626, 127052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment. The Installation, Management and Operation Manual of Facility Reducing Non-Point Source Pollution; Korea Environment Corporation: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Case | Specimen ID | Mixture Proportion (%) | Dry Unit Weight (kN/m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom Ash | Silica Sand | |||

| The same compaction time (i.e., 25 s) 1 | A00 | 0 | 100 | 14.46 |

| A50 3 | 50 | 50 | 12.65 | |

| A100 | 100 | 0 | 7.49 | |

| The same unit weight 2 | A30 | 30 | 70 | 12.65 |

| A50 3 | 50 | 50 | ||

| A70 | 70 | 30 | ||

| Case | Specimen ID | Permeability Coefficient (mm/s) | Standard Deviation (mm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The same compaction time | A00 | 5.79 | 0.073 |

| A50 1 | 4.85 | 0.053 | |

| A100 | 8.75 | 0.104 | |

| The same unit weight | A30 | 5.23 | 0.131 |

| A50 1 | 4.85 | 0.053 | |

| A70 | 4.26 | 0.033 |

| Specimen ID | Standard Deviation (%) |

|---|---|

| A00 | 14 |

| A30 | 5 |

| A50 | 2 |

| A70 | 5 |

| A100 | 14 |

| Particulate Matter | Standard Deviation (%) |

|---|---|

| 1.8 μm | 5 |

| 10 μm | 3 |

| 60 μm | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.; Lee, D.; Lee, H.; Choe, H.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, Y.; Ahn, J. Removal Efficiency of Bottom Ash and Sand Mixtures as Filter Layers for Fine Particulate Matter. Materials 2024, 17, 2749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112749

Lee Y, Lee D, Lee H, Choe H-S, Kim J-H, Choi Y, Ahn J. Removal Efficiency of Bottom Ash and Sand Mixtures as Filter Layers for Fine Particulate Matter. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112749

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yunje, Donghyun Lee, Hongkyoung Lee, Hyun-Seok Choe, Jae-Hyuk Kim, Yongjin Choi, and Jaehun Ahn. 2024. "Removal Efficiency of Bottom Ash and Sand Mixtures as Filter Layers for Fine Particulate Matter" Materials 17, no. 11: 2749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112749

APA StyleLee, Y., Lee, D., Lee, H., Choe, H.-S., Kim, J.-H., Choi, Y., & Ahn, J. (2024). Removal Efficiency of Bottom Ash and Sand Mixtures as Filter Layers for Fine Particulate Matter. Materials, 17(11), 2749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112749