Effects of Prior Microstructure on the Properties of Induction-Hardened JIS SCM440 Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Prior Heat Treatment of Specimens

2.2. Induction Hardening of Different Prior Treated Specimens

2.3. Characterizations of Induction-Hardened Specimens

2.3.1. Microstructure

2.3.2. Microhardness

2.3.3. X-Ray Diffraction

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Microstructure of Specimens Before and After Induction-Hardening Treatment

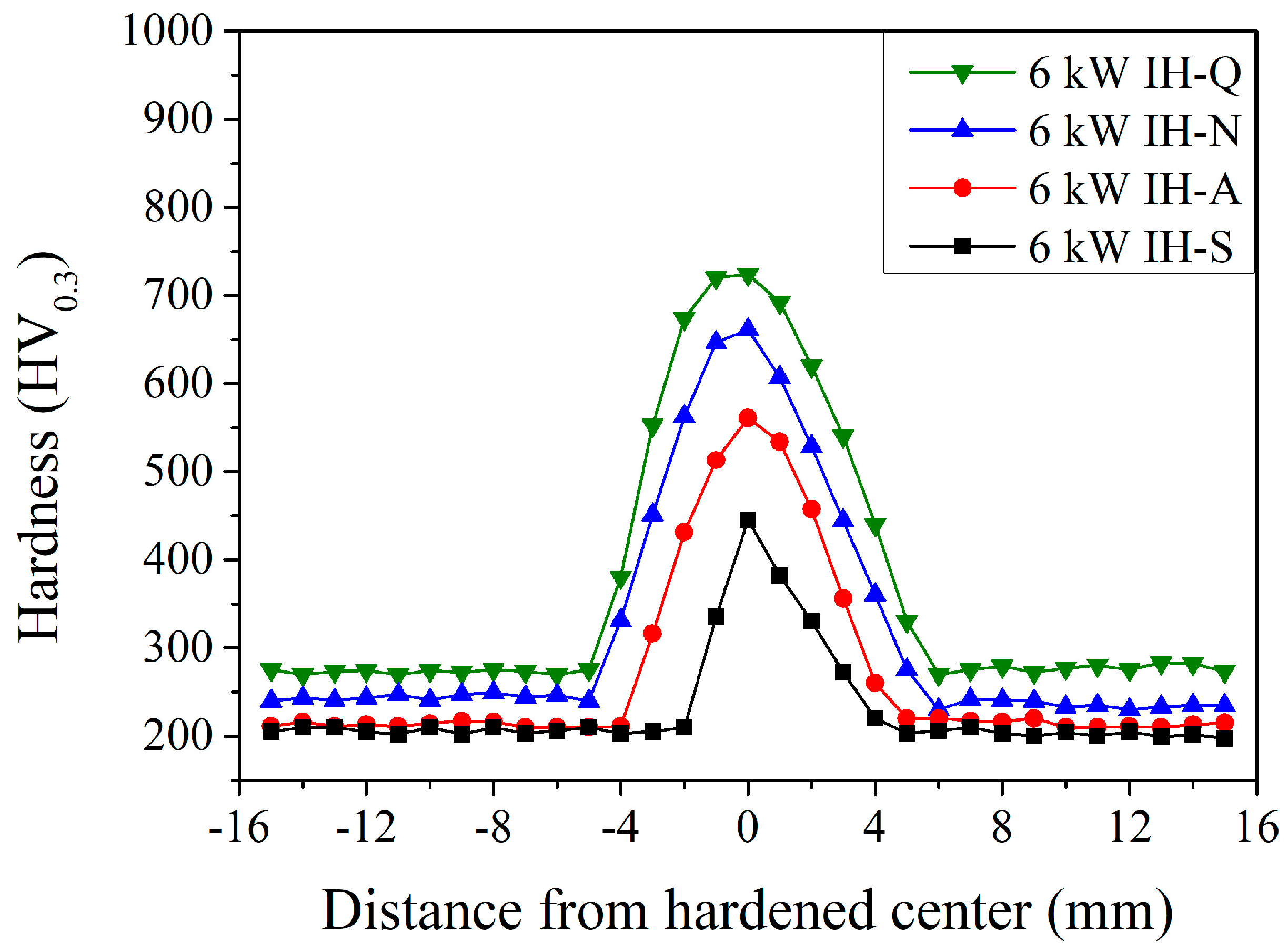

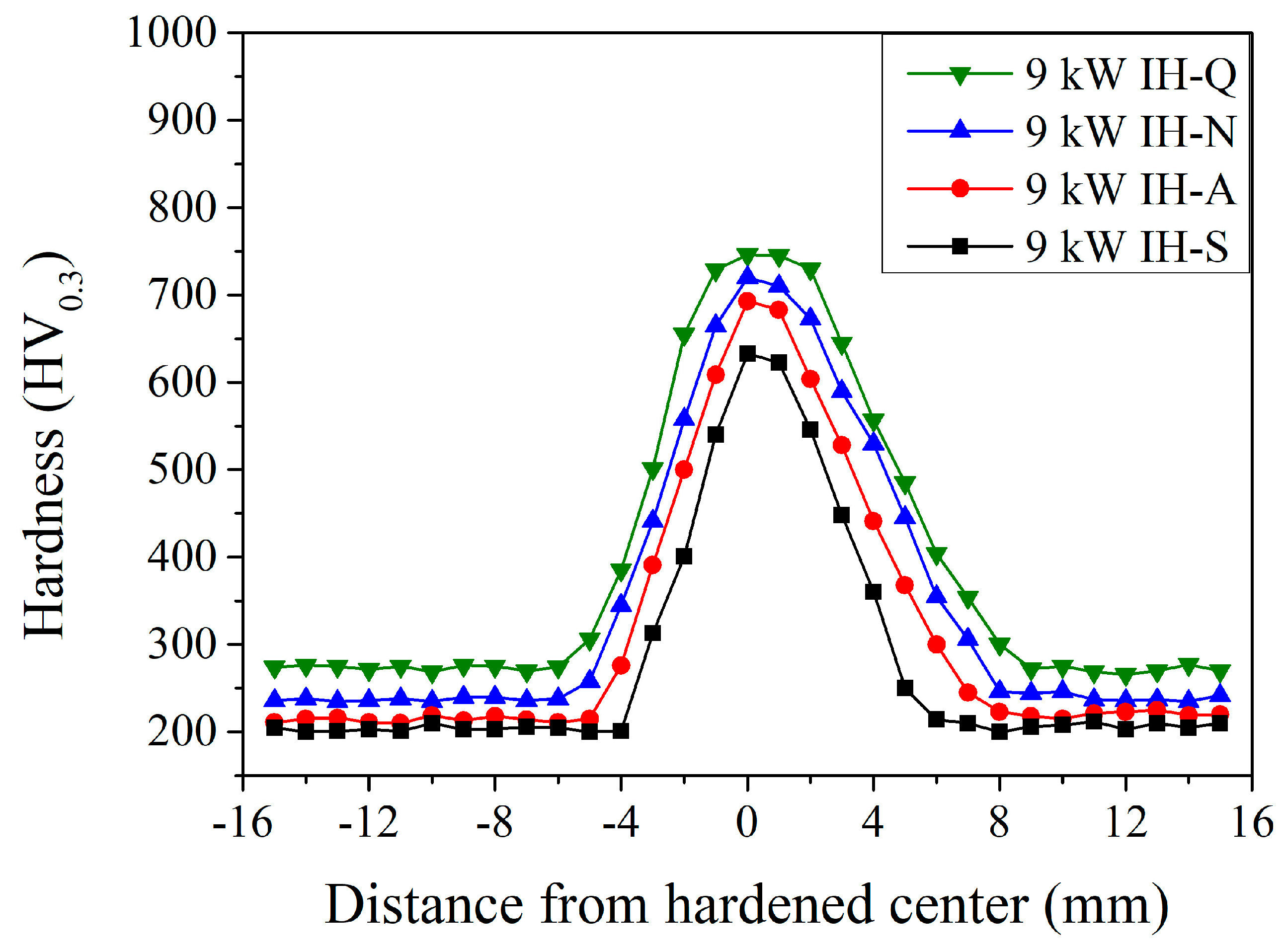

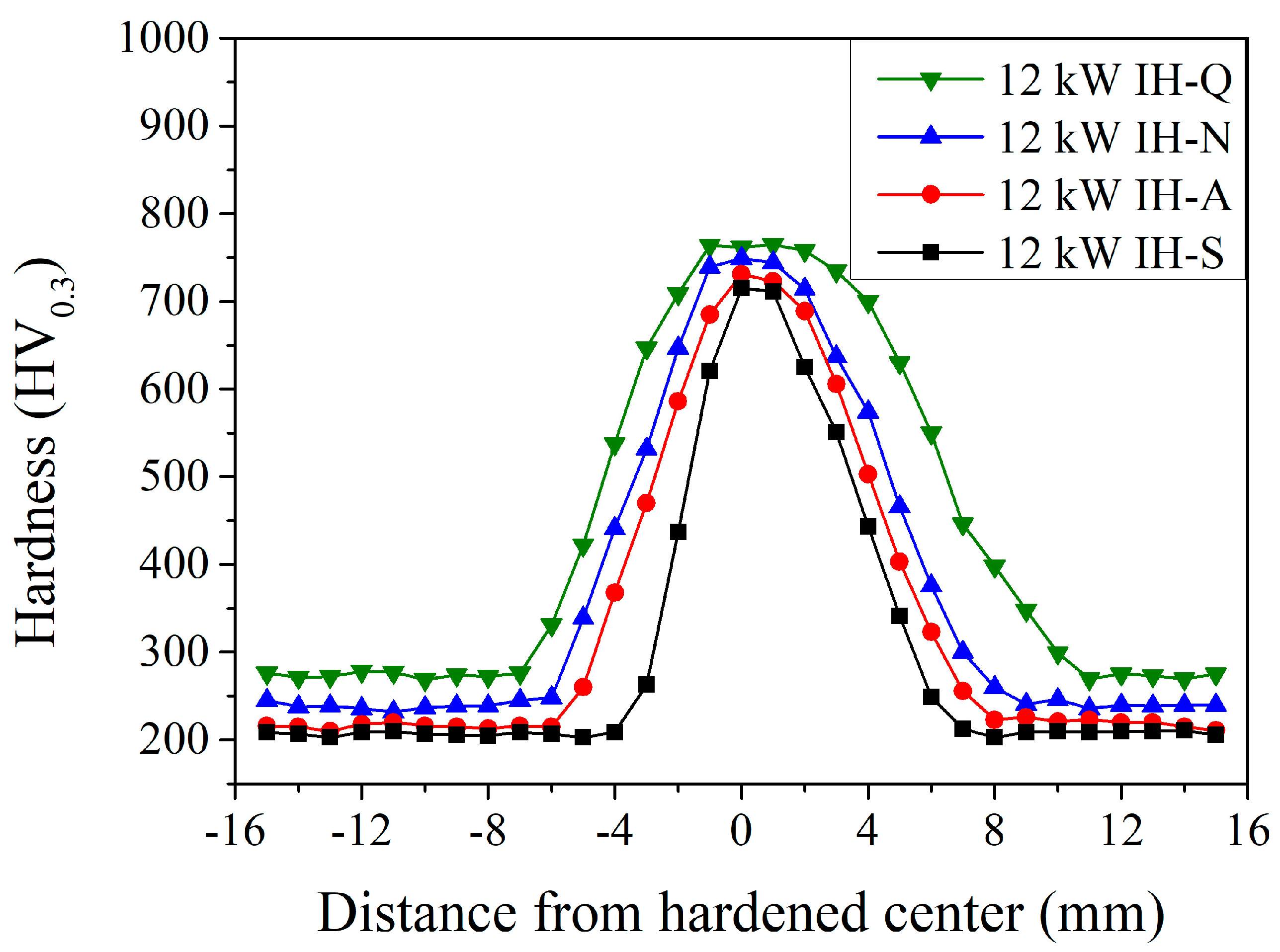

3.2. The Microhardness Distribution of Different Prior Microstructure Specimens After Induction-Hardening Treatment

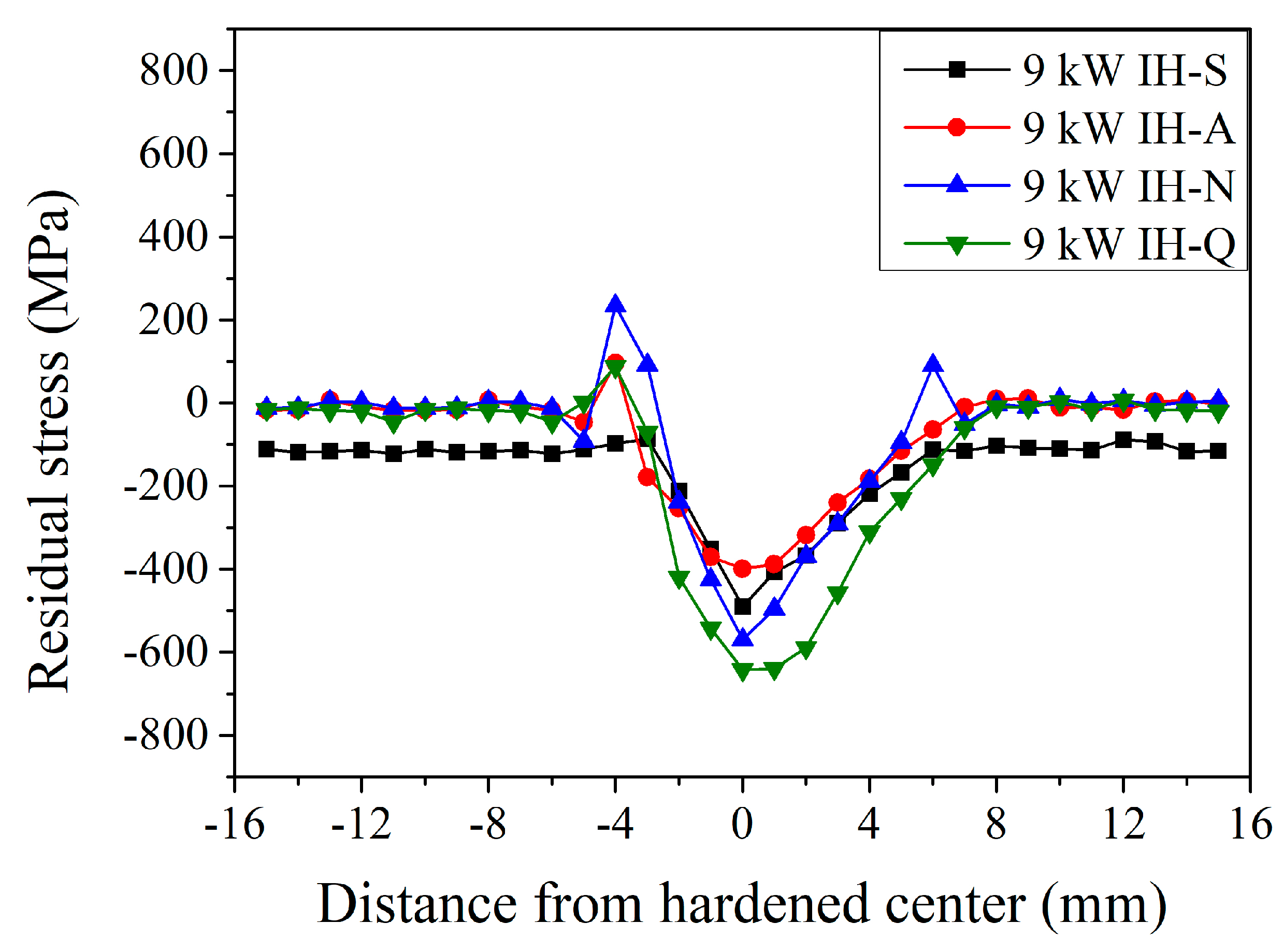

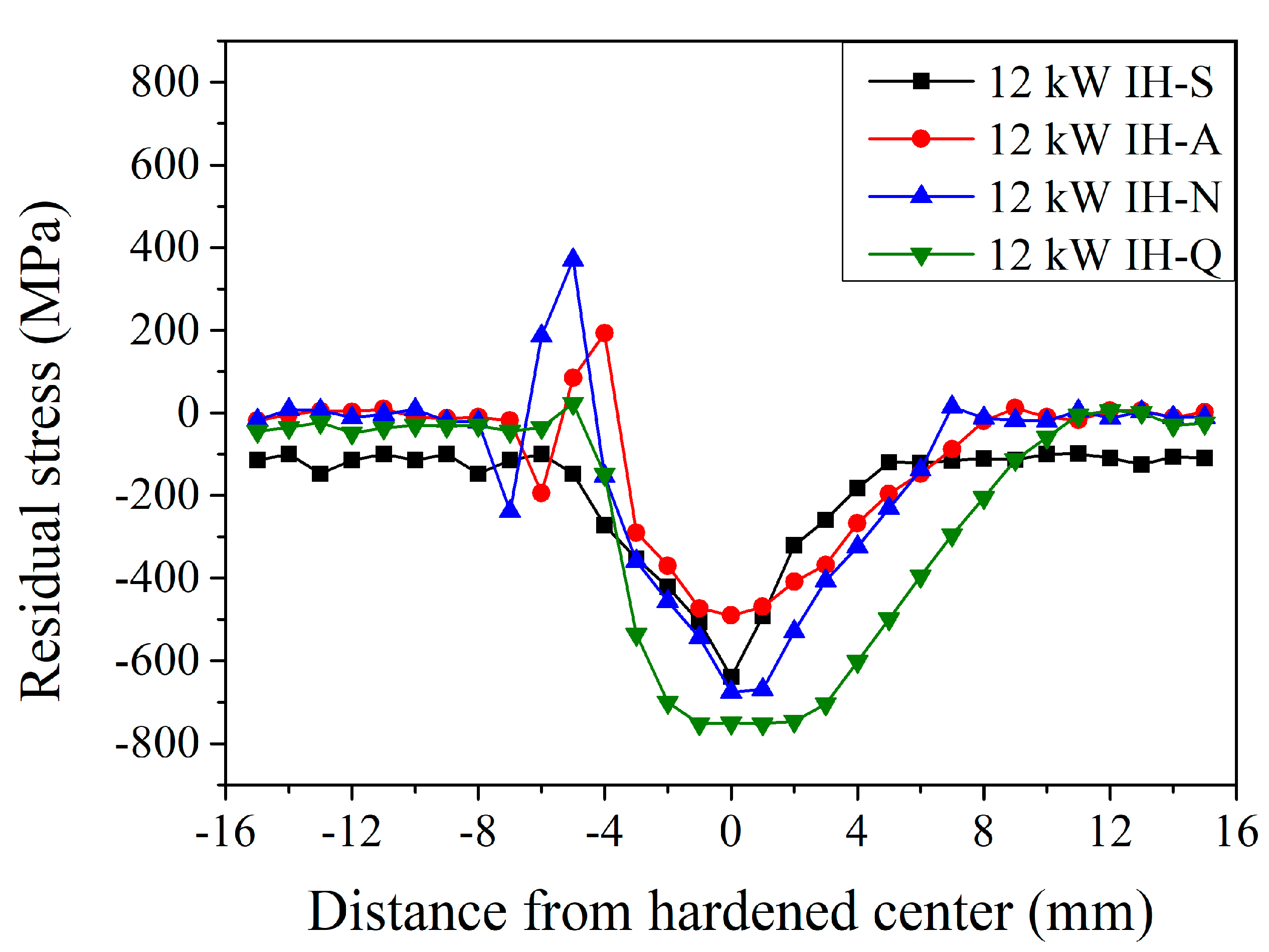

3.3. The Surface Residual Stress Distribution of Different Prior Microstructure Specimens After Induction-Hardening Treatment

4. Conclusions

- The prior microstructure can effectively influence the hardened region after induction-hardening treatment, and the difference in the cooling rate caused the delayed quenched area to have a wider hardened affected area than that of the immediately quenched area.

- The distribution of residual stress in the hardened zone and heat-affected zone is due to the temperature gradient of the induction-hardening treatment. The hardened center appeared as compressive residual stress due to the martensitic transformation, which was accompanied by volume expansion. On the contrary, tensile residual stress will be generated in the heat-affected zone of incomplete phase transformation and plastic distortion.

- The prior microstructure will effectively affect the maximum microhardness and the width of the hardened area. The smaller size of the cementite in the prior microstructure will increase the amount of the cementite that dissolved into the austenite at high temperatures. This resulted in an increase in the carbon content of the martensite and increased the hardness and width of the hardened area. The induction-hardened specimen with a quenched and tempered prior microstructure has the highest microhardness at the hardened center and the widest hardened area. The maximum microhardness and the hardened width of the induction-hardened specimen with a quenched and tempered prior microstructure were 762 HV0.3 and 16 mm after induction-hardening treatment at a power of 12 kW.

- Induction hardening effectively distributes the residual compressive stress on the surface of the hardened area and is affected by the prior microstructure. The specimen with a quenched and tempered prior microstructure after induction hardening treatment at a power of 12 kW resulted in the optimal effect. The maximum residual stress reached −750 MPa (at the hardened center) and the stress-changed area was also the widest (18 mm). Moreover, the presented residual tensile stress was only 23 MPa.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badaruddin, M.; Sugiyanto; Wardono, H.; Andoko; Wang, C.J.; Rivai, A.K. Improvement of low-cycle fatigue resistance in AISI 4140 steel by annealing treatment. Int. J. Fatigue 2019, 125, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhong, H.; Lei, L.; Fang, G. Microstructure and mechanical properties of multi-pass forged and annealed 42CrMo steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wettlaufer, M. Plane-strain fracture toughness of AISI 4140 steel austempered below MS. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 743, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Frankenbach, T.; Wettlaufer, M. Strengthening 42CrMo4 steel by isothermal transformation below martensite start temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 683, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areitioaurtena, M.; Segurajauregi, U.; Akujarvi, V.; Fisk, M.; Urresti, I.; Ukar, E. A semi-analytical coupled simulation approach for induction heating. Adv. Model. Simul. Eng. Sci. 2021, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-K.; Park, K.-S.; Lee, S.-S. Prediction of high-frequency induction hardening depth of an AISI 1045 specimen by finite element analysis and experiments. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2018, 19, 1821–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Qin, O.; Wu, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. Fatigue resistance and remaining life assessment of induction-hardened S38C steel railway axles. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 144, 106068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areitioaurtena, M.; Segurajauregi, U.; Akujarvi, V.; Fisk, M.; Cabello, M.J.; Ukar, E. Influence of induction hardening residual stresses on rolling contact fatigue lifetime. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 159, 106781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheenady, A.A.; Arakere, N.K.; Londhe, N.D. Accounting for microstructure sensitivity and plasticity in life prediction of heavily loaded contacts under rolling contact fatigue. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2020, 43, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa Ngan, N.; Bocher, P. Finite element analysis simulation of the effect of induction hardening on rolling contact fatigue. J. Tribol. 2018, 140, 061404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.W.; Pan, X.N.; Han, J.; Zhu, S.P.; Liao, D.; Li, Y.B.; Dai, G.Z. Influence of artificial defects on fatigue strength of induction hardened S38C axles. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 139, 105746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayama, M.; Kikuchi, S.; Tsukahara, M.; Misaka, Y.; Komotori, J. Estimation of residual stress relaxation in low alloy steel with different hardness during fatigue by in situ X-ray measurement. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 178, 107989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Z.; Jiang, X.H.; Yang, J.G.; Liang, S.Y. Effects of depth of cut on the redistribution of residual stress and distortion during the milling of thin-walled part. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2015, 216, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, R.; Löpenhaus, C.; Gomes, J.; Klock, F. Residual stress interaction on gear manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 252, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S.; Minamizawa, K.; Arakawa, J.; Akebono, H.; Takesue, S.; Hayakawa, M. Combined effect of surface morphology and residual stress induced by fine particle and shot peening on the fatigue limit for carburized steels. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 168, 107441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hömberg, D.; Liu, Q.; Montalvo-Urquizo, J.; Nadolski, D.; Petzold, T.; Schmidt, A.; Schulz, A. Simulation of multi-frequency-induction-hardening including phase transitions and mechanical effects. Finite Elem. Anal. 2016, 121, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, D.; Damon, J.; Mühl, F.; de Graaff, B.; Kiefer, D.; Dietrich, S.; Schulze, V. Experimental investigation and finite-element modeling of the short-time induction quench-and-temper process of AISI 4140. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 279, 116485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, M.; Lindgren, L.E.; Datchary, W.; Deshmukh, V. Modelling of induction hardening in low alloy steels. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2018, 144, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-S.; Huang, Y.-L. Effect of multi-layered induction coils on efficiency and uniformity of surface heating. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2010, 53, 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Kuki, K. An evaluation of mechanical properties with the hardness of building steel structural members for reuse by NDT. Metals 2016, 6, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strodick, S.; Vogel, F.; Tilger, M.; Denstorf, M.; Kipp, M.; Baak, N.; Kukui, D.; Biermann, D.; Barrientos, M.M.; Walther, F. Innovative X-ray diffraction and micromagnetic approaches for reliable residual stress assessment in deep rolled and microfinished AISI 4140 components. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 2942–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desisa, D.; Smalcerz, A.; Kotlan, V.; Barglik, J.; Smagor, A.; Dolezel, I. Mathematical modelling of thermal stresses of induction surface hardening in axi-symmetric formulation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 479, 130516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areitioaurtena, M.; Segurajauregi, U.; Fisk, M.; Cabello, M.J.; Ukar, E. Numerical and experimental investigation of residual stresses during the induction hardening of 42CrMo4 steel. Eur. J. Mech. A/Solids 2022, 96, 104766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grum, J. A review of the influence of grinding conditions on resulting residual stresses after induction surface hardening and grinding. J. Mater. Process. 2001, 114, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, S.S.; Li, C.J.; Huang, Y.F.; Luo, Z. Determination of residual stress in resistance spot-welded joint by a novel X-ray diffraction. Measurement 2020, 161, 107892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K. The cosα method for X-ray residual stress measurement using two-dimensional detector. Mech. Eng. Rev. 2019, 6, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rico, J.; Lee, S.; Ling, J.; Noyan, I.C. Stress measurement using area detectors: A theoretical and experimental comparison of different methods in ferritic steel using a portable X-ray apparatus. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 5343–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H. Cementite. Int. Mater. Rev. 2020, 65, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaee, M.; Betiku, O.T.; Tolton, C.; Midawi, A.R.H.; Ramachandran, D.; Zhang, T.; Ghassemi-Armaki, H.; Worswick, M.; Biro, E. Investigating the Mechanical Properties and Failure Behavior of Groups of Resistance Spot Welds under Tensile-Bending Loading Conditions. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr * | Ni | Mo* | Cu | Fe. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JIS SCM440 Spec. | 0.38–0.43 | 0.15–0.35 | 0.60–0.85 | ≤0.030 | ≤0.030 | 0.90–1.20 | ≤0.25 | 0.15–0.30 | ≤0.30 | Bal. |

| Specimens | 0.415 | 0.214 | 0.663 | 0.0099 | 0.0108 | 0.925 | 0.0473 | 0.164 | 0.101 | Bal. |

| Surface Hardness | |

|---|---|

| Prior Heat Treatment | |

| Spheroidized (S) | 12 HRC |

| Annealed (A) | 80 HRB |

| Normalized (N) | 92 HRB |

| Quenched and Tempered (Q) | 29 HRC |

| Sample | Power (kW) | Prior Treat * |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | S |

| 2 | 9 | |

| 3 | 12 | |

| 4 | 6 | A |

| 5 | 9 | |

| 6 | 12 | |

| 7 | 6 | N |

| 8 | 9 | |

| 9 | 12 | |

| 10 | 6 | Q |

| 11 | 9 | |

| 12 | 12 |

| Diffractometer Parameters | Specification/Values |

|---|---|

| Tube type | Cr (λ = 0.229093 nm) |

| Diffraction plane (h, k, l) | αFe(211) |

| Bragg angle for diffraction (2θ) | 156.5° |

| Current | 1.5 mA |

| Voltage | 30 kV |

| Exposure time | 15 s |

| Collimator diameter | 1 mm |

| Collimator distance | 51 mm |

| Tube type | Cr (λ = 0.229093 nm) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, S.-Q.; Chiu, L.-H.; Cheng, H.-H. Effects of Prior Microstructure on the Properties of Induction-Hardened JIS SCM440 Steel. Materials 2025, 18, 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18051045

Lu S-Q, Chiu L-H, Cheng H-H. Effects of Prior Microstructure on the Properties of Induction-Hardened JIS SCM440 Steel. Materials. 2025; 18(5):1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18051045

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Shao-Quan, Liu-Ho Chiu, and Hsueh-Hung Cheng. 2025. "Effects of Prior Microstructure on the Properties of Induction-Hardened JIS SCM440 Steel" Materials 18, no. 5: 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18051045

APA StyleLu, S.-Q., Chiu, L.-H., & Cheng, H.-H. (2025). Effects of Prior Microstructure on the Properties of Induction-Hardened JIS SCM440 Steel. Materials, 18(5), 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18051045