Substrate Preference Determines Macrofungal Biogeography in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Sampling Area and Study Plots

2.2. Macrofungal Species Sampling and Recording of Substrate Observations

2.3. Macrofungal Identification and Classification of Substrates

2.4. Substrate Utilization Analysis

2.5. Correlation Between Macrofungal Taxonomic Diversity and Substrate Utilization

3. Results

3.1. Substrate-Specific Composition of Macrofungi

3.2. Macrofungal Species Occupying Multiple Substrates

3.3. Correlation between Macrofungal Taxonomic Diversity and Diversity of Its Substrates

4. Discussion

4.1. Substrate Specificity Drives the Biogeography of Macrofungi

4.2. Multiple-Substrates Macrofungi form Pioneer Fungal Communities

4.3. Substrate Diversity is Correlated with Fungal Taxonomic Diversity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heijden, M.G.; Bardgett, R.D.; Van Straalen, N.M. The unseen majority: Soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, P.A.; Last, F.T.; Pelham, J.; Ingleby, K. Ecology of Some Fungi Associated with an Aging Stand of Birches (Betula pendula and Betula pubescens). For. Ecol. Manag. 1982, 4, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, R.M.; Visser, S. Effects of forest soil acidification on ectomycorrhizal and vesicular—Arbuscular mycorrhizal development. New Phytol. 1989, 112, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watling, R. Pulling the Threads Together: Habitat Diversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 1997, 6, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterseher, M.; Tal, O. Influence of small scale conditions on the diversity of wood decay fungi in a temperate, mixed deciduous forest canopy. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, G.M.; Ratkowsky, D.A. Comparing indigenous and European-based concepts of seasonality for predicting macrofungal fruiting activity in Tasmania. Australas. Mycol. 2009, 28, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lodge, D.J.; Ammirati, J.F.; O’Dell, T.E.; Gregory, M.M. Collecting and Describing Macrofungi, Biodiversity of Fungi Inventory and Monitoring Methods; Elsevier Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 128–158. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265425189 (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Tibuhwa, D.D. Substrate specificity and phenology of macrofungi community at the University of Dar es Salaam Main Campus, Tanzania. Appl. Sci. 2011, 46, 3173–3184. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, D.; Hershey, H. Mushrooms Demystified; Ten Speed Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, G.M.; Schmit, J.P. Fungal biodiversity: What do we know? What can we predict? Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiewska, M. Macrofungi on special substrates. In Fungi in Vegetation Science; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 151–182. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, R.; Söderström, B. Mycorrhiza and Carbon Flow to the Soil; Mycorrhizal Functioning. Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 134–160. [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert, J.V.; Van Laere, A.; van Assche, J.A. Carbon and nitrogen allocation in ectomycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal Pinus sylvestris L. seedlings. Tree Physiol. 1996, 16, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, D.R.; Pellitier, P.T.; Argiroff, W.; Castillo, B.; James, T.Y.; Nave, L.E.; Colon, A.; Kaitlyn, V.B.; Jennifer, B.; Jennifer, B.; et al. Exploring the role of ectomycorrhizal fungi in soil carbon dynamics. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, W.A.; Lyon, H.H. Diseases of Trees and Shrubs, 2nd ed.; Comstock Publishing Associates: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, J.P.; Hughes, D.P. Diversity of entomopathogenic fungi: Which groups conquered the insect body? Adv. Genet. 2016, 94, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Gbadamassi, D.G.; Ekananda, P.; Zang, H.; Xu, J.; Harrison, R.D. Changes in fungal communities across a forest disturbance gradient. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e00080-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dix, N.J.; Webster, J. Fungi of Soil and Rhizosphere. In Fungal Ecology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 172–202. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, H.; Gohbara, M.; Tsuda, M.; Fujimori, T. Evaluation of fungal pathogens as biological control agents for the paddy weed, Echinochloa species by drop inoculation. Jpn. J. Phytopathol. 1997, 63, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, D.; Boonstra, A.; Kennedy, G. Managing Information Systems: Strategy and Organisation; Pearson Education: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Osono, T. Decomposing ability of diverse litter-decomposer macrofungi in subtropical, temperate, and subalpine forests. J. For. Res. 2015, 20, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pradhan, P.; Dutta, A.K.; Roy, A.; Basu, S.K.; Acharya, K. Inventory and spatial ecology of macrofungi in the Shorea robusta forest ecosystem of lateritic region of West Bengal. Biodiversity 2012, 13, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.L.; Mortimer, P.E.; Slik, J.W.F.; Zou, X.M.; Xu, J.C.; Feng, W.T.; Qiao, L. Variation in forest soil fungal diversity along a latitudinal gradient. Fungal Divers. 2014, 64, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, D.J. Factors related to diversity of decomposer fungi in tropical forests. Biodivers. Conserv. 1997, 6, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, B.; Gadek, P.; Hyde, K.D. Estimation of microfungal diversity in tropical rainforest leaf litter using particle filtration: The effects of leaf storage and surface treatment. Mycol. Res. 2003, 107, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, O.M.; Soytong, K.; Hyde, K.D. Diversity of entomopathogenic fungi in rainforests of Chiang Mai Province. Thail. Fungal Divers. 2008, 30, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Luckert, M.K.; Williamson, T. Should sustained yield be part of sustainable forest management? Can. J. For. Res. 2005, 35, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Miguel, S.; Bonet, J.A.; Pukkala, T.; de-Aragón, J.M. Impact of forest management intensity on landscape-level mushroom productivity: A regional model-based scenario analysis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 330, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, J.; Karunarathna, S.; Ye, L.; Xu, J.; Hyde, K.; Mortimer, P. Native Forests Have a Higher Diversity of Macrofungi Than Comparable Plantation Forests in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Forests 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halling, R.E. Recommendations for collecting mushrooms. Adv. Econ. Bot. 1996, 10, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, P.; Martins, A.; Tavares, R.M.; Lino-Neto, T. Diversity and fruiting pattern of macrofungi associated with chestnut (Castanea sativa) in the Trás-os-Montes region (Northeast Portugal). Fungal Ecol. 2010, 3, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A.; Corbet, A.S.; Williams, C.B. The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. J. Anim. Ecol. 1943, 12, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heltshe, J.F.; Forrester, N.E. Estimating species richness using the jackknife procedure. Biometrics 1983, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellerberg, I.F.; Fedor, P.J. A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the ‘Shannon–Wiener’ Index. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieller, E.C.; Hartley, H.O.; Pearson, E.S. Tests for rank correlation coefficients. I. Biometrika 1957, 44, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, J.W.G. Evolution of mycorrhiza systems. Naturwissenschaften 2000, 87, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinhut, T.; Hadar, Y.; Chen, Y. Degradation and transformation of humic substances by saprotrophic fungi: Processes and mechanisms. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, J.A.; Lindner, D.L. Use of fungal biosystematics and molecular genetics in detection and identification of wood-decay fungi for improved forest management. For. Pathol. 2011, 41, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osono, T.; Matsuoka, S.; Hirose, D.; Uchida, M.; Kanda, H. Fungal colonization and decomposition of leaves and stems of Salix arctica on deglaciated moraines in high-Arctic Canada. Polar Sci. 2014, 8, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osono, T. Diversity, resource utilization, and phenology of fruiting bodies of litter-decomposing macrofungi in subtropical, temperate, and subalpine forests. J. For. Res. 2015, 20, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osono, T. Effects of litter type, origin of isolate, and temperature on decomposition of leaf litter by macrofungi. J. For. Res. 2015, 20, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Epps, M.J.; Arnold, A.E. Interaction networks of macrofungi and mycophagous beetles reflect diurnal variation and the size and spatial arrangement of resources. Fungal Ecol. 2019, 37, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanen, D.K.; Eggleton, P.; Rouland-Lefevre, C.; Guldberg-Frøslev, T.; Rosendahl, S.; Boomsma, J.J. The evolution of fungus-growing termites and their mutualistic fungal symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14887–14892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindahl, B.D.; Tunlid, A. Ectomycorrhizal fungi–potential organic matter decomposers, yet not saprotrophs. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bödeker, I.; Lindahl, B.D.; Olson, Å.; Clemmensen, K.E. Mycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungal guilds compete for the same organic substrates but affect decomposition differently. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gregorio, A.P.F.; Da Silva, I.R.; Sedarati, M.R.; Hedger, J.N. Changes in production of lignin degrading enzymes during interactions between mycelia of the tropical decomposer basidiomycetes Marasmiellus troyanus and Marasmius pallescens. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, S.; Boddy, L. Interactions between saprotrophic fungi. In British Mycological Society Symposia Series; Elsevier Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 28, pp. 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, C.Y.; Husaini, A.; Hussain, H.; Muid, S.; Liew, K.C.; Roslan, H.A. Lignin biodegradation and ligninolytic enzyme studies during biopulping of Acacia mangium wood chips by tropical white rot fungi. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 1457–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Svenning, J.C.; Wang, X.; Cao, R.; Yuan, Z.; Ye, Y. Drivers of Macrofungi Community Structure Differ between Soil and Rotten-Wood Substrates in a Temperate Mountain Forest in China. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halling, R.E. Ectomycorrhizae: Co-evolution, significance, and biogeography. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2001, 88, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ostermann, A.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Xu, J.; Hyde, K.D.; Mortimer, P.E. The importance of plot size and the number of sampling seasons on capturing macrofungal species richness. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, T.R.; Bruns, T.D. Multiple-host fungi are the most frequent and abundant ectomycorrhizal types in a mixed stand of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and bishop pine (Pinus muricata). New Phytol. 1998, 139, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frankenberger, W.; Dick, W.A. Relationships Between Enzyme Activities and Microbial Growth and Activity Indices in Soil 1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1983, 47, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaní, A.M.; Fischer, H.; Mille-Lindblom, C.; Tranvik, L.J. Interactions of bacteria and fungi on decomposing litter: Differential extracellular enzyme activities. Ecology 2006, 87, 2559–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.H.; Klironomos, J.N.; Henry, H.A. Seasonal responses of extracellular enzyme activity and microbial biomass to warming and nitrogen addition. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2010, 74, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, P.; Reis, F.; Pereira, E.; Tavares, R.M.; Santos, P.M.; Richard, F.; Lino-Neto, T. Soil DNA pyrosequencing and fruitbody surveys reveal contrasting diversity for various fungal ecological guilds in chestnut orchards. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2015, 7, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González, G.; Lodge, D. Soil biology research across latitude, elevation and disturbance gradients: A review of forest studies from Puerto Rico during the past 25 Years. Forests 2017, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meentemeyer, V. Macroclimate and lignin control of litter decomposition rates. Ecology 1978, 59, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Sha, L.; Song, Q.; Zhang, X. Effects of Litter Inputs on N 2 O Emissions from a Tropical Rainforest in Southwest China. Ecosystems 2018, 21, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Pang, M.; Fanin, N.; Wang, H.; Qian, S.; Zhao, L.; Ma, K. Fungi participate in driving home-field advantage of litter decomposition in a subtropical forest. Plant Soil 2019, 434, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, E.; Dossa, G.G.; de Blécourt, M.; Beckschäfer, P.; Xu, J.; Harrison, R.D. Quantifying the factors affecting leaf litter decomposition across a tropical forest disturbance gradient. Ecosphere 2015, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

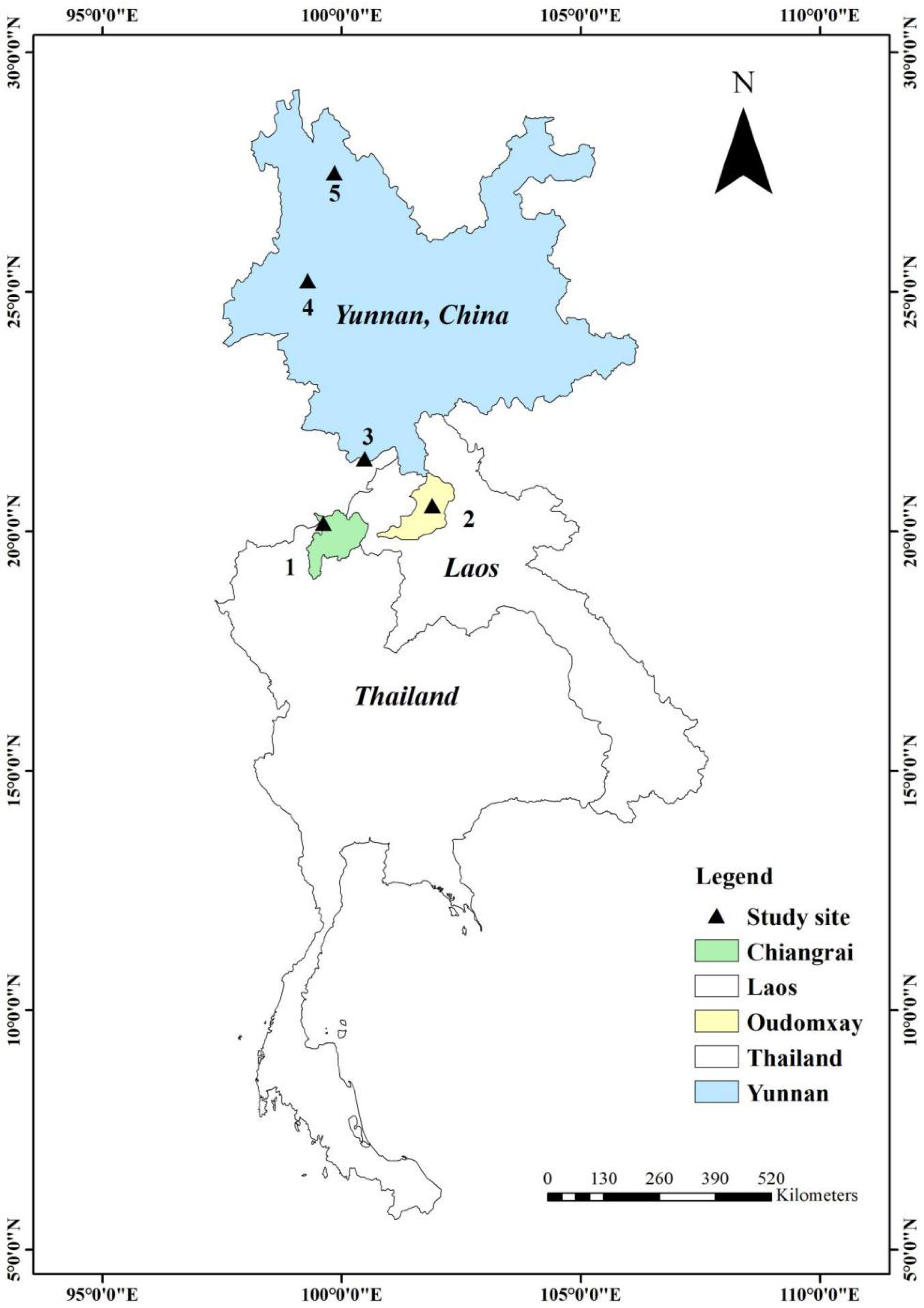

| Study Site | Location | GPS Coordinates (Long., Lat.) | Elevation (m) | MT/MR (°C/mm) | Climate | Dominant Tree Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-ZD (15 Plots) | Zhongdian, China | 99.8633 °E, 27.4733 °N | 3100–3300 | 12.3/82.4 | Temperate | Pinus densata, Picea likiangensis, Rhododendron rubiginosum |

| B-BS (15 Plots) | Baoshan, China | 99.2882 °E, 25.2566 °N | 2400–2600 | 21/127.2 | Temperate | Pinus armandii, Pinus yunnanensis, Castanopsis orthacantha, Quercus rehderiana |

| C-MS (15 Plots) | Mengsong, China | 100.4898 °E, 21.4946 °N | 1500–1700 | 25.7/164.4 | Subtropical | Syzygium brachythyrsum, Xanthophyllum flavescens, Macaranga henryi, Cryptocarya hainanensis, Myrsine seguinii, Anneslea fragrans |

| D-LS (12 Plots) | Oudomxay, Laos | 101.8967 °E, 20.5335 °N | 700–900 | 25.4/232.7 | Tropical | Castanopsis spp., Lithocarpus spp., Cephalostachyum virgatum, Dendrocalamus strictus, Oxytenanthera paviflora, Coffea arabica |

| E-TL (9 plots) | Chiang Rai, Thailand | 99.62305 °E, 20.16833 °N | 980–1300 | 27/211.3 | Tropical | Lithocarpus elegans, Castanopsis tribuloides, Castanopsis diversifolia, Castanopsis calathiformis, Hevea brasiliensis, Coffea arabica, Pinus kesiya |

| Major Substrate Category | Substrate Subgroup | Family | Genus | Species | Dominant Fungal Species | ECT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root | Root (R) | 54 | 97 | 443 | Laccaria laccata | ECM |

| Litter | Total Litter | 45 | 91 | 342 | ||

| Log wood (LW) | 45 | 78 | 220 | Amauroderma rugosum | SAC | |

| Dead leaf (DL) | 24 | 36 | 86 | Marasmius aff. siccus | SAC | |

| Rotten leaf (RL) | 10 | 15 | 27 | Collybia aff. dryophila | SAC | |

| Branch wood (BW) | 2 | 2 | 2 | Mycena lactea | SAC | |

| Fruit (FT) | 2 | 2 | 2 | Auriscalpium vulgare | SAC | |

| Tree wood (TW) | 4 | 4 | 4 | Hypholoma fasciculare | SAC | |

| Twig (TG) | 11 | 15 | 35 | Marasmius chordalis | SAC | |

| Soil | Total Soil | 25 | 42 | 172 | ||

| O-Soil (OS) | 22 | 39 | 167 | Clitopilus apalus | SAC | |

| M-Soil (MS) | 3 | 3 | 5 | Leucocoprinus fragilissimus | SAC | |

| Rare | Total Rare | 10 | 15 | 30 | ||

| Dung (DG) | 5 | 9 | 9 | Stropharia semiglobata | SAC | |

| Fungal fruiting body (FB) | 2 | 2 | 2 | Hypomyces sp. | PAC | |

| Insect (IT) | 4 | 6 | 8 | Ophiocordyceps nutans | PAC | |

| Lichen (LN) | 2 | 2 | 2 | Lichenomphalia sp.1 | BYC | |

| Termite-nest (TN) | 2 | 2 | 9 | Termitomyces bulborhizus | BYC |

| A: Category | Genus | Dominant Genus | B: Substrate Subgroup in Litter Category | Genus | Dominant Genus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litter Root Soil | 2 | Entoloma | DL LW RL TG | 2 | Mycena |

| Litter Soil Rare | 5 | Marasmius | DL LW RL | 1 | Psathyrella |

| Root Soil | 1 | Phaeocollybia | DL LW TG | 2 | Marasmiellus |

| Litter Soil | 17 | Clitocybe | LW RL TG | 1 | Coprinus |

| Litter Rare | 6 | Favolaschia | DL LW | 8 | Hohenbuehelia |

| Soil Rare | 2 | Conocybe | DL RL | 4 | Clitocybe |

| Root | 52 | Heimioporus | LW TG | 4 | Cyathus |

| Litter | 61 | Echinoporia | DL | 8 | Aphelaria |

| Soil | 25 | Megacollybia | LW | 56 | Antrodiella |

| Rare | 10 | Multiclavula | RL | 3 | Lycoperdon |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, L.; Li, H.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J.; Gui, H.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Kumar, A.; Hyde, K.D.; Shi, L. Substrate Preference Determines Macrofungal Biogeography in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region. Forests 2019, 10, 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100824

Ye L, Li H, Mortimer PE, Xu J, Gui H, Karunarathna SC, Kumar A, Hyde KD, Shi L. Substrate Preference Determines Macrofungal Biogeography in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region. Forests. 2019; 10(10):824. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100824

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Lei, Huili Li, Peter E. Mortimer, Jianchu Xu, Heng Gui, Samantha C. Karunarathna, Amit Kumar, Kevin D. Hyde, and Lingling Shi. 2019. "Substrate Preference Determines Macrofungal Biogeography in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region" Forests 10, no. 10: 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100824

APA StyleYe, L., Li, H., Mortimer, P. E., Xu, J., Gui, H., Karunarathna, S. C., Kumar, A., Hyde, K. D., & Shi, L. (2019). Substrate Preference Determines Macrofungal Biogeography in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region. Forests, 10(10), 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10100824