Forest Management Practices and Costs for Family Forest Landowners in Georgia, USA

Abstract

:1. Introduction

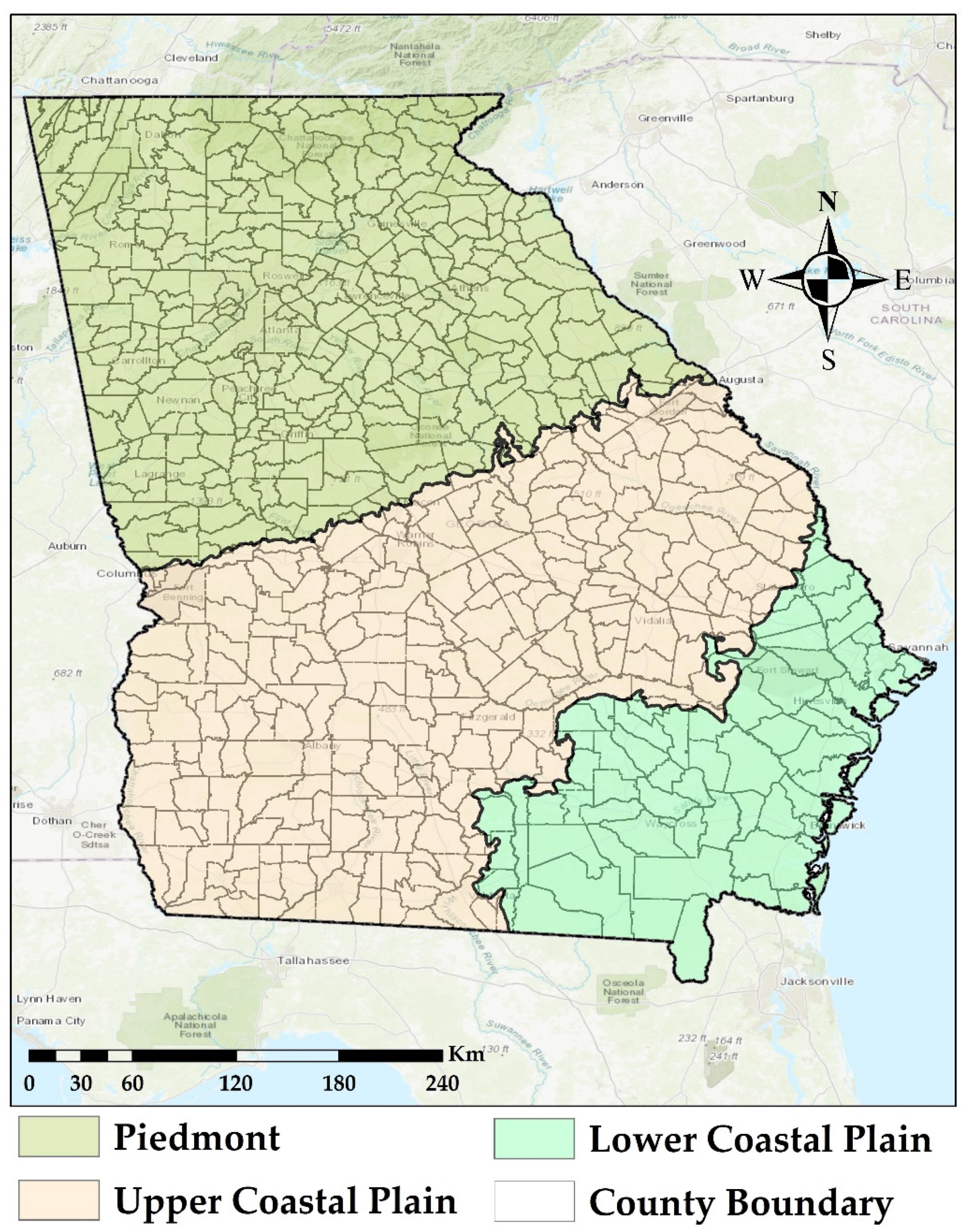

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Common Forest Management Activities

3.1.1. Rotation and Thinning Age

3.1.2. Plantation Choices

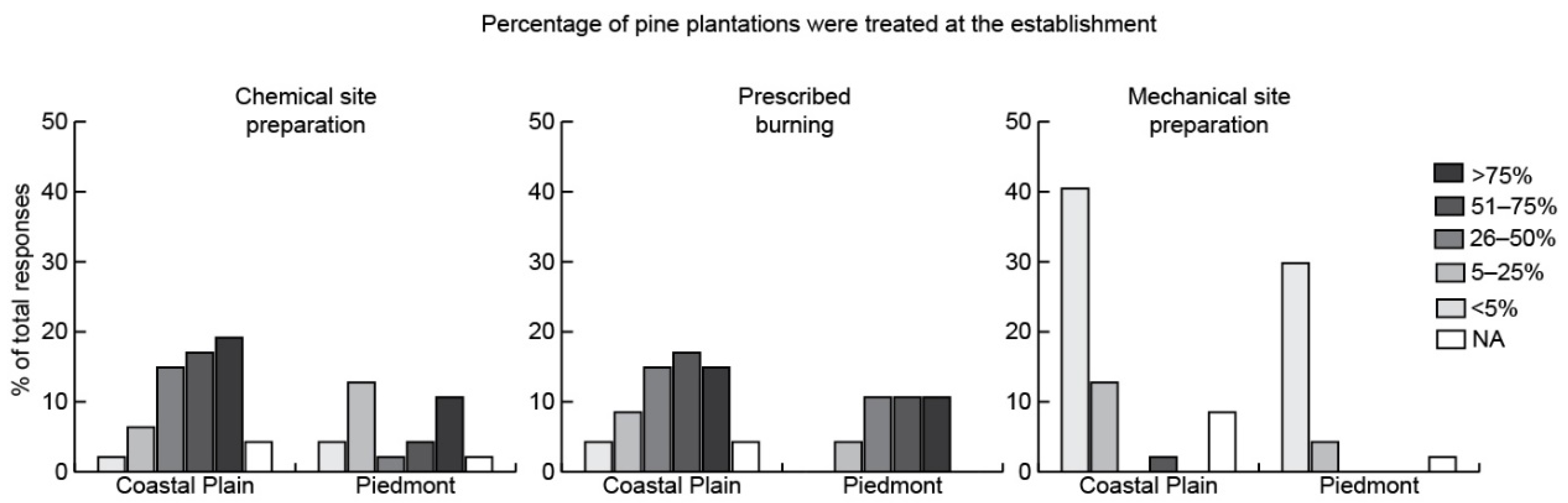

3.1.3. Site Preparation Operations

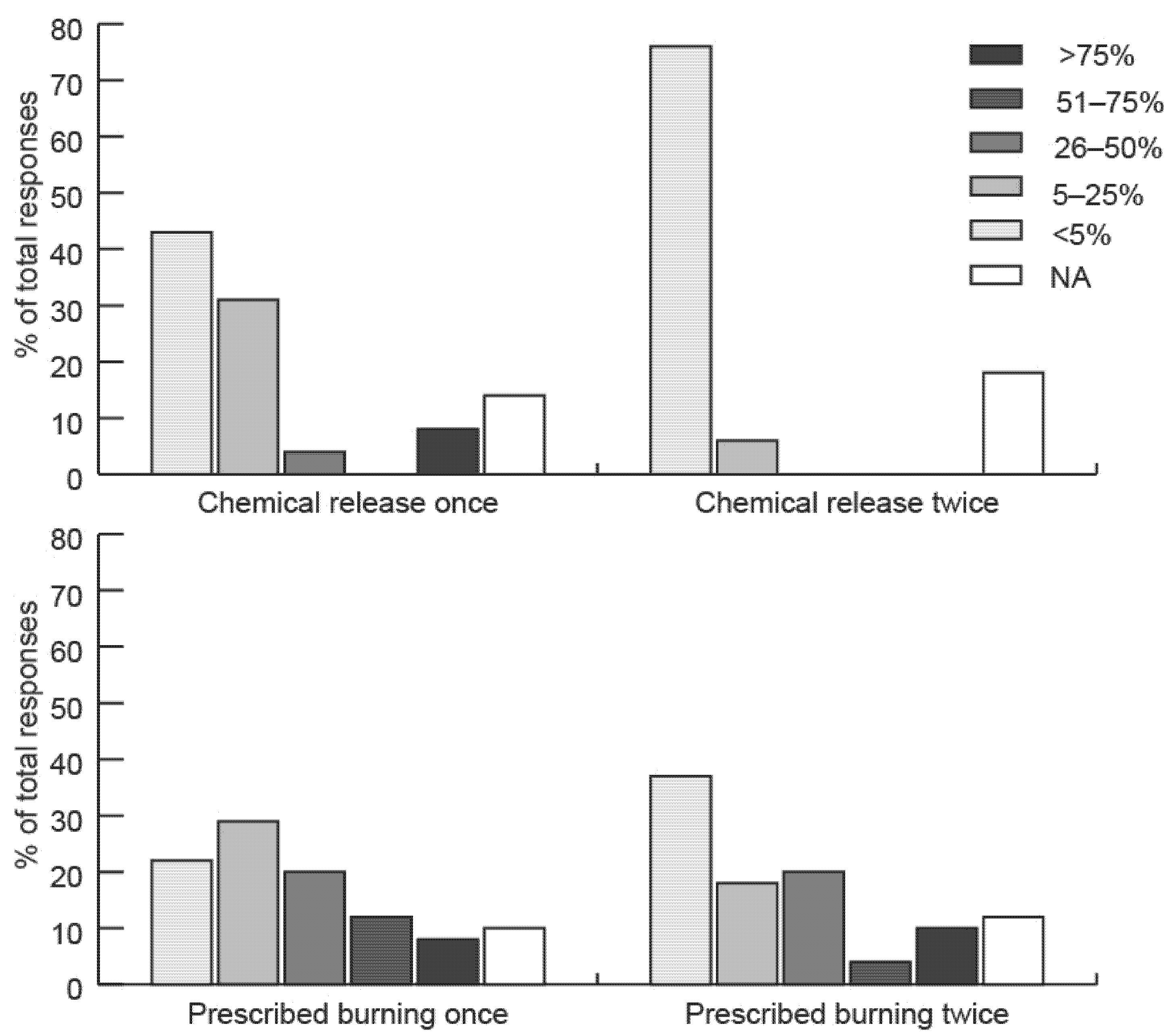

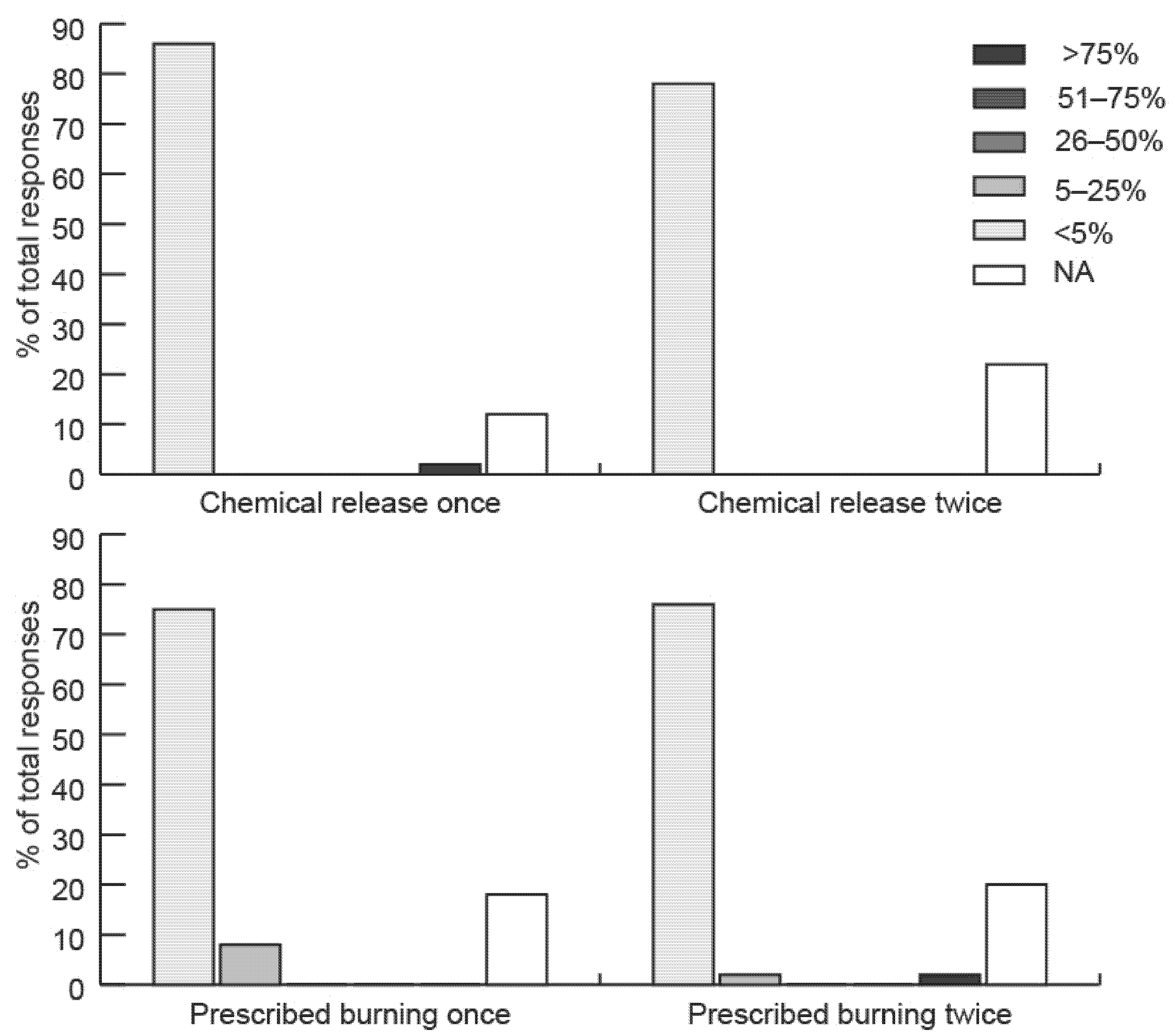

3.1.4. Other Forest Management Activities during a Rotation

3.2. Costs Associated with Forest Management Activities

3.2.1. Forest Management Plan Preparation Fee

3.2.2. Site Preparation Planting Costs

3.2.3. Mid-Rotation Control

3.2.4. Timber Sale Administration Costs

3.2.5. Other Forest Management Costs

3.3. Non-Timber Income from Forests

3.3.1. Hunting Leases

3.3.2. Income from Pine Straw

3.4. Opinions on the Trends of Forest Management Practices

- The respondents believed that an important portion of Georgia’s forest landowners generate income from hunting leases;

- Many survey respondents agreed that prescribed burning is being increasingly used in Georgia. It indicated that landowners were conscious of protecting their forest lands from wildland forest fires and unwanted species;

- The survey respondents agreed that the usage of chemical release has increased. It suggested that landowners were increasingly concerned about forest health and productivity;

- Reforestation has increasingly gained popularity among forest landowners;

- Forest management of hardwoods is mostly custodial (e.g., paying taxes and maintaining boundaries) in Georgia.

4. Discussion

4.1. Status and Trends in Georgia Family Landowners’ Forest Management

4.2. Forest Management Costs

4.3. Opportunities and Issues

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Georgia Forestry Commission. Georgia Statewide Assessment of Forest Resources 2015; Georgia Forestry Commission: Dry Branch, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, B.J.; Butler, S.M. Family Forest Ownerships with 10+ Acres in Georgia, 2011–2013; USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2016.

- Georgia Forestry Commission. Economic Benefits of the Forest Industry in Georgia Statewide Assessment of Forest Resources: 2018; Georgia Forestry Commission: Dry Branch, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, S.M.; McRoberts, R.E.; Mahal, L.G.; Carr, M.A.; Alig, R.J.; Comas, S.J.; Theobald, D.M.; Cundiff, A. Private Forests, Public Benefits: Increased Housing Density and Other Pressures on Private Forest Contributions; USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2009.

- Moore, R.; Williams, T.; Rodriguez, E.; Hepinstall-Cymmerman, J. Quantifying the Value of Non-Timber Ecosystem Services from Georgia’s Private Forests; Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brandeis, T.J.; McCollum, J.; Hartsell, A.; Brandeis, C.; Rose, A.K.; Oswalt, S.N.; Vogt, J.T.; Marcano-Vega, H. Georgia’s Forests, 2014; USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2016.

- USDA Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis Program. Forest Inventory EVALIDator Web-Application Version 1.8.0.01; USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2021.

- Conway, M.C.; Amacher, G.S.; Sullivan, J.; Wear, D. Decisions nonindustrial forest landowners make: An empirical examination. J. For. Econ. 2003, 9, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, D.; Wear, D. Production economics of private forestry: A comparison of industrial and nonindustrial forest Owners. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1993, 75, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanayak, S.; Murray, B.; Abt, R. How joint is joint forest production? An econometric analysis of timber supply conditional on endogenous amenity values. For. Sci. 2002, 48, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.J.; Butler, S.M.; Caputo, J.; Dias, J.; Robillard, A.; Sass, E.M. Family Forest Ownerships of the United States, 2018: Results from the USDA Forest Service, National Woodland Owner Survey; USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Madison, WI, USA, 2021.

- Zhang, D.; Warren, S.; Bailey, C. The role of assistance foresters in nonindustrial private forest management: Alabama landowners’ perspectives. South. J. Appl. For. 1998, 22, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Mehmood, S. Predicting nonindustrial private forest landowners’ choices of a forester for harvesting and tree planting assistance in Alabama. South. J. Appl. For. 2001, 25, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larson, D.; Hardie, I. Seller behavior in stumpage markets with imperfect information. Land Econ. 1989, 65, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, I.A.; Rucker, R.R. Predicting forestry consultant participation based on physical characteristics of timber sales. J. For. Econ. 1998, 4, 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Maggard, A.; Barlow, R. Special Report: 2016 Costs and Trends for Southern Forestry Practices; Forest Landowner: Carrollton, GA, USA, 2017; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan, D.W.; Khanal, P.N.; Straka, T.J. An analysis of costs and cost trends for southern forestry practices. J. For. 2019, 117, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F&W Forestry Services. Hunting Leases; F&W Forestry Report: Albany, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, D.G.; Cubbage, F.W. Private forestry consultants: 1983 status and accomplishments in Georgia. South. J. Appl. For. 1986, 10, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.G.; Cubbage, F.W. Nonindustrial private forest management in the South: Assistance foresters’ activities and perceptions. South. J. Appl. For. 1990, 14, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Sedjo, R.A. Is this the age of intensive management? A study of loblolly pine on Georgia’s Piedmont. J. For. 2001, 99, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alig, R.J.; Lee, K.J.; Moulton, R.J. Likelihood of Timber Management on Nonindustrail Private Forests: Evidence from Research Studies; USDA Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 1990.

- Fox, T.R.; Jokela, E.J.; Allen, H.L. The development of pine plantation silviculture in the southern United States. J. For. 2007, 105, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, K. 2019 Georgia Farm Gate Value Report; University of Georgia Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development: Athens, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.F.; Barlow, R.J.; Kush, J.S.; Gilbert, J.C. Pine Straw Production: From Forest to Front Yard. In Proceedings of the 16th Biennial Southern Silvicultural Research Conference, Charleston, SC, USA, 14–17 February 2011; pp. 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; p. 523. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, H.S., IV; Marsinko, A.P.; Guynn, D.C. Forest Industry Hunt-Lease Programs in the Southern United States: 1999. In Proceedings of the Fifty-Fifth Annual Conference of Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, SEAFWA, Louisville, KY, USA, 13–17 October 2001; pp. 567–574. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.; Pienaar, L.; Aronow, M. The productivity and profitability of fiber farming. J. For. 1998, 96, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, D. A spatial panel data analysis of tree planting in the US South. South. J. Appl. For. 2007, 31, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jokela, E.J.; Stearns-Smith, S.C. Fertilization of established southern pine stands: Effects of single and split nitrogen treatments. South. J. Appl. For. 1993, 17, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, E.D.; Moorhead, D.J.; Kissel, D.E.; Morris, L.A. Mid-Rotation Rate of Return (ROR) Estimates with a Single Nitrogen+Phosphorus or Nitrogen+Phosphorus+Potassium Fertilizer Application in Loblolly, Longleaf, and Slash Pine Stands; Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maggard, A.; Barlow, R. 2018 Costs and Trends for Southern Forestry Practices; FOR-2073; Auburn University (AL), Alabama Cooperative Extension System: Auburn, AL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clabo, D.; Peairs, S.; Dickens, E.D. Managing Upland Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest Types for Georgia Landowners; WSFNR-19-50; Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, W.C.; Munn, I.A. 2013 Fees and Services of Mississippi’s Consulting Foresters; Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University: Starkville, MS, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C.C.; Munn, I.A. Fees and Services of Consulting Foresters in Mississippi; Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University: Starkville, MS, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Godar Chhetri, S.; Gordon, J.; Munn, I.; Henderson, J. Comparison of the timber management expenses of non-industrial private forest landowners in Mississippi, United States: Results from 1995–1997 and 2015. Environments 2019, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rhyne, J.D.; Munn, I.A.; Hussain, A. Hedonic analysis of auctioned hunting leases: A case study of Mississippi Sixteenth Section Lands. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2009, 14, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hussain, A.; Armstrong, J.B. Supply of hunting leases from non-industrial private forest lands in Alabama. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2006, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, I.A.; Hussain, A. Factors determining differences in local hunting lease rates: Insights from Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Land Econ. 2010, 86, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingie, J.C.; Poudyal, N.C.; Bowker, J.M.; Mengak, M.T.; Siry, J.P. A hedonic analysis of big game hunting club dues in Georgia, USA. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2017, 22, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.D. Bottomland Hardwoods: Valuable, Vanishing, Vulnerable; Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Services, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | # of Surveyed Foresters | # of Respondents | % of Surveyed Foresters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credentials | |||

| Registered forester | 178 | 47 | 25.68 |

| Certified prescribed burner | 102 | 25 | 23.81 |

| Real estate license holder | 101 | 25 | 24.75 |

| Society of American Foresters member | 73 | 20 | 27.03 |

| Society of American Foresters certified forester | 27 | 12 | 44.44 |

| Association of Consulting Foresters member | 27 | 10 | 35.71 |

| Certified real estate appraiser | 18 | 5 | 26.32 |

| Registered land surveyor | 9 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Service Region | |||

| Both regions | 115 | 29 | 25.22 |

| Coastal Plains only | 40 | 12 | 30.00 |

| Piedmont only | 28 | 6 | 21.43 |

| Services Provided | |||

| Timber cruising | 170 | 46 | 26.29 |

| Forest product sales | 172 | 45 | 25.42 |

| Timber marking | 159 | 41 | 25.00 |

| Forest management plan | 163 | 40 | 23.81 |

| Damage and trespass appraisals | 135 | 35 | 25.00 |

| Land acquisition | 109 | 28 | 25.00 |

| Wildlife management | 100 | 27 | 26.21 |

| Forest stewardship plan | 111 | 26 | 22.61 |

| Investment counseling | 62 | 17 | 26.56 |

| Real estate brokerage | 59 | 16 | 26.23 |

| Forest litigation | 60 | 13 | 21.31 |

| Recreational land development | 69 | 12 | 16.90 |

| Taxes | 38 | 9 | 23.68 |

| Resource investigation and economic studies | 46 | 8 | 17.02 |

| Timber loans | 15 | 4 | 25.00 |

| Environmental services: | |||

| Water quality | 34 | 4 | 11.43 |

| Endangered species | 24 | 2 | 8.33 |

| Wetlands & permitting | 22 | 1 | 4.55 |

| Impact studies | 22 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Vendor Services | |||

| Prescribed burning: | |||

| Provide personally | 117 | 28 | 23.14 |

| Subcontract | 66 | 22 | 32.35 |

| Mechanical site preparation: | |||

| Provide personally | 24 | 4 | 16.67 |

| Subcontract | 136 | 41 | 29.29 |

| Herbaceous chemical control: | |||

| Provide personally | 43 | 6 | 13.95 |

| Subcontract | 134 | 41 | 29.50 |

| Woody chemical control: | |||

| Provide personally | 38 | 6 | 15.79 |

| Subcontract | 135 | 40 | 28.57 |

| Tree planting: | |||

| Provide personally | 36 | 8 | 22.22 |

| Subcontract | 128 | 38 | 28.57 |

| Physiographic Region /Forest Type | Timber Stand Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

| Coastal Plain: | ||||||

| Pine plantation | ||||||

| First thinning | 19 | 15 | 11 | 18 | 15 | 1.75 |

| Second thinning | 16 | 20 | 15 | 25 | 21 | 2.73 |

| Final harvest | 24 | 30 | 20 | 38 | 29 | 4.66 |

| Natural pine | ||||||

| First thinning | 17 | 20 | 14 | 60 | 23 | 11.62 |

| Second thinning | 14 | 29 | 8 | 60 | 31 | 14.58 |

| Final harvest | 17 | 40 | 25 | 60 | 40 | 9.8 |

| Hardwoods | ||||||

| Final harvest | 11 | 50 | 40 | 80 | 47 | 15.67 |

| Piedmont: | ||||||

| Pine plantation | ||||||

| First thinning | 14 | 15.5 | 10 | 18 | 16 | 1.15 |

| Second thinning | 13 | 22 | 20 | 25 | 22 | 1.72 |

| Final harvest | 16 | 30 | 25 | 40 | 21 | 3.74 |

| Natural pine | ||||||

| First thinning | 8 | 23.5 | 16 | 70 | 32 | 20.78 |

| Second thinning | 6 | 32.5 | 22 | 60 | 37 | 14.97 |

| Final harvest | 8 | 37.5 | 35 | 60 | 41 | 8.63 |

| Hardwoods | ||||||

| Final harvest | 6 | 45 | 40 | 70 | 50 | 12.25 |

| Item | Coastal Plain | Piedmont | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median | Interquartile Range | N | Median | Interquartile Range | N | Median | Interquartile Range | |

| Management plan ($/plan) | 16 | 1200 | 750–2000 | 8 | 875 | 637.5–1750 | 24 | 1100 | 575–2000 |

| Site preparation ($/acre) | |||||||||

| Mechanical (shear-pile bedding) | 18 | 237.5 | 195–300 | 5 | 125 | 123–132 | 23 | 210 | 123–270 |

| Chemical site prep | 28 | 85 | 70–90 | 14 | 85 | 80–90 | 42 | 85 | 75–90 |

| Windrow (shear and pile) | 14 | 175 | 150–300 | * | * | * | 16 | 175 | 125–300 |

| Burning | 26 | 20 | 15–25 | 14 | 25 | 20–28 | 40 | 21 | 15.5–25.5 |

| Planting ($/acre) | |||||||||

| Machine planting | 28 | 90 | 67.5–95 | 13 | 90 | 85–100 | 41 | 90 | 80–95 |

| Hand planting | 26 | 72.5 | 60–81 | 13 | 65 | 60–70 | 39 | 65 | 60–80 |

| Forest management ($/acre) | |||||||||

| Herbaceous weed control | 23 | 40 | 35–49 | 11 | 40 | 30–42 | 34 | 40 | 35–45 |

| Mid-rotation woody control | 17 | 65 | 50–75 | 10 | 55 | 40–75 | 27 | 60 | 50–75 |

| Miscellaneous ($/acre unless otherwise specified) | |||||||||

| Land surveying * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Boundary line establishment ($/mile) | 13 | 250 | 180–450 | * | * | * | 17 | 300 | 180–450 |

| Boundary line maintenance ($/mile) | 15 | 200 | 150–300 | 6 | 250 | 160–350 | 21 | 200 | 160–300 |

| Road construction * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Road maintenance * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Prescribed burning ($/acre) | 25 | 20 | 15–25 | 12 | 21 | 20–25 | 37 | 20 | 16–25 |

| Firebreak establishment ($/hr) | 22 | 85 | 60–100 | 8 | 95 | 75–100 | 20 | 87.5 | 65–100 |

| Firebreak maintenance ($/hr) | 19 | 80 | 58.75–96.25 | 6 | 95 | 72.5–97.5 | 25 | 85 | 57.5–97.5 |

| Pre-commercial thinning ($/acre) | 10 | 112.5 | 80–200 | 6 | 142.5 | 115–175 | 16 | 132.5 | 100–187.5 |

| Timber stand improvement ($/acre) | 6 | 70 | 34–110 | * | * | * | 8 | 90 | 47–120 |

| Timber sale administration | |||||||||

| Turnkey operation (mark, cruise, advertise, sell, and supervise timber sale) † | 19 | 10% | 8–10% | 7 | 10% | 8–12% | 25 | 10% | 8–10% |

| Cruise only ($/acre) | 28 | 10 | 8–10 | 11 | 10 | 8–10 | 38 | 10 | 8–10 |

| Mark only ($/acre) | 22 | 35 | 16–45 | 8 | 32.5 | 16.25–42.5 | 30 | 35 | 16–45 |

| Supervise timber sale only † | 22 | 5% | 5–7% | 9 | 9% | 7–10% | 31 | 6% | 5–8.5% |

| Region and Statistic Measures | Pines | Hardwoods | Mixed Forests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Forest Land Leased for Hunting Purposes | |||

| Coastal Plain | |||

| N | 30 | 29 | 30 |

| Mean | 74% | 64% | 67% |

| Median | 78% | 75% | 78% |

| 25th–75th percentile | 70–90% | 25–90% | 40–90% |

| Piedmont | |||

| N | 22 | 21 | 18 |

| Mean | 75% | 68% | 66% |

| Median | 78% | 75% | 75% |

| 25th–75th percentile | 60–95% | 50–95% | 30–95% |

| Georgia State-wide Average | |||

| N | 41 | 40 | 40 |

| Mean | 73% | 64% | 68% |

| Median | 75% | 75% | 75% |

| 25th–75th percentile | 60–85% | 28.8–90% | 50–90% |

| Annual Hunting Lease Rate (per Acre) | |||

| N | 41 | 40 | 41 |

| Mean (per acre) | $10.36 | $11.93 | $11.54 |

| Median (per acre) | $10 | $12 | $12 |

| 25th–75th percentile (per acre) | $9.7–$12 | $10–$14.5 | $10–$12.5 |

| Additional Annual Costs Associated with Providing Hunting Services | |||

| N | 30 | 30 | 29 |

| Mean (per acre) | $5.69 | $9.51 | $3.01 |

| Median (per acre) | $2 | $2 | $2 |

| 25th–75th percentile (per acre) | $0–$7 | $0–$7 | $0–$6 |

| Statistic Measures | Percentage of Longleaf Pine Used for Pine Straw Production | Annual Income from Pine Straw Sale (per Acre) |

|---|---|---|

| N | 21 | 18 |

| Mean | 49% | $165.83 |

| Median | 50% | $150 |

| 25th–75th percentile | 20–75% | $100–$200 |

| Statement | Mean | Median |

|---|---|---|

| The usage of artificial regeneration has increased | 0.76 | 1 |

| The usage of chemical release has increased | 0.76 | 1 |

| The usage of prescribed burning has increased | 0.30 | 1 |

| More landowners choose to plant pines after a clearcutting | 1.07 * | 1 |

| A very small percentage of landowners regularly collect income from selling pine straw | 0.87 | 1 |

| A very small percentage of landowners regularly collect income from hunting leases on their forest land | −0.62 | −1 |

| Forest management on hardwoods is mostly custodial (e.g., paying taxes and maintaining boundaries) | 1.11 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godar Chhetri, S.; Parker, J.; Izlar, R.L.; Li, Y. Forest Management Practices and Costs for Family Forest Landowners in Georgia, USA. Forests 2022, 13, 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13050665

Godar Chhetri S, Parker J, Izlar RL, Li Y. Forest Management Practices and Costs for Family Forest Landowners in Georgia, USA. Forests. 2022; 13(5):665. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13050665

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodar Chhetri, Sagar, Jake Parker, Robert L. Izlar, and Yanshu Li. 2022. "Forest Management Practices and Costs for Family Forest Landowners in Georgia, USA" Forests 13, no. 5: 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13050665

APA StyleGodar Chhetri, S., Parker, J., Izlar, R. L., & Li, Y. (2022). Forest Management Practices and Costs for Family Forest Landowners in Georgia, USA. Forests, 13(5), 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13050665