1. Introduction

In 1992 the European Union (EU) adopted Council Directive 92/43 of 21 May 1992 [

1] on the conservation of natural habitats and wild fauna and flora. This created the Natura 2000 network, a European ecological network made up of Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), in which the aim is to ensure the maintenance and/or restoration of natural habitats. Today, the Natura 2000 network occupies around 18% of the European Union’s surface area [

2,

3].

The scientific literature on the subject indicates multiple benefits of the Natura 2000 network in social, economic and environmental aspects, for example [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Nevertheless, several studies have claimed that its declaration and subsequent management have not been able to prevent the loss of natural habitats [

8,

9,

10]. It has also been mentioned that the selection of areas to be protected was not based on scientific criteria [

11], which makes it difficult to achieve the desired objectives [

12,

13,

14,

15].

The designation of areas to be protected has also been met, in many cases, with opposition from landowners [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], who have protested in defence of traditional management methods and their property rights [

22]. As examples, some authors have mentioned the hunger strike of forest owners in Karvia (Finland) in response to the introduction of the Natura 2000 network [

23], while other authors argued that the designation of these areas could also alter the economic conditions of land users and land prices, and that acceptance by interests (i.e., landowners and farmers) is a key aspect for conservation effectiveness [

24].

With regard to this social opposition, it is necessary to remember that forest fires in Europe are the main cause of destruction of forest area [

25,

26]. They are also one of the greatest threats to this type of protected area. In 2007, in Greece, forest fires affected 12.4% of the Peloponnese Natura 2000 network [

27,

28]. It is therefore necessary to consider the existence of a certain relationship between forest fires and social conflicts [

29,

30,

31], as the Natura network affects the population of these areas in many ways and can lead to various conflicts. Several authors, for example, have linked ineffective forestry policies to the occurrence of forest fires [

32,

33,

34]. In addition, protectionist measures may lead to land abandonment due to depreciation, which causes landowner rejection and can lead to an increase in the number of fires [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Regos et al., in a study published in 2013 [

39], linked the occurrence of forest fires to the increase in forest area in Catalonia (Spain), and Farina, in 1998, [

40] reported that the loss of land value favoured its abandonment and increased the risk of fires. The presence of shrub and grassland is also associated with an increase in number of fires [

41,

42,

43]. In any case, a better understanding of the causes of the conflict will provide sufficient and realistic knowledge to support the choice of future policies in relation to natural protection [

44].

Considering that 95% of forest fires in Europe are arson [

45,

46,

47] or are related to human activity [

48], it is essential to scientifically analyse the causality and incidence of forest fires in areas considered legally protected entities, as forest fires affect ecosystem resources and services (tourism, protection, biomass production, biodiversity conservation) [

49], hinder the development of policies on the improvement of forest spaces [

50] and cause natural disasters such as erosive phenomena, desertification and loss of biodiversity [

51].

Considering a specific region of northwestern Spain, the autonomous community of Galicia, this study proposes a statistical analysis to verify the effect that the legal declaration of protected zones to preserve their natural value may have had on the occurrence and evolution of arson activity and, more specifically, to determine whether the inclusion of a specific form of collective private property, the monte vecinal en mano común (MVMC), in the Natura 2000 network has meant a change in this arson activity.

We analysed whether the implementation of the Natura network regulations led to any change in the fire regime in the areas of collective private property in Galicia. Therefore, the analysis, which covers the period 1999–2014, focuses on analysing the differences between the sub-periods 1999–2004 and 2005–2014, as it was in December 2004 when the list of sites of community importance in the Atlantic biogeographical region, the region in which the study area is located, was approved. The aim of the article, finally, is to answer the following questions:

Is there a significant difference in the number of fires and/or the area burnt/fire before and after 2004 in the SACs?

In the MVMC-SAC intersection zone, is there a significant difference in the number of fires and/or in the area burnt/fire before and after 2004?

After 2004, was there a significant difference in the fire regimes of MVMCs with SAC and MVMCs without SAC?

3. Results

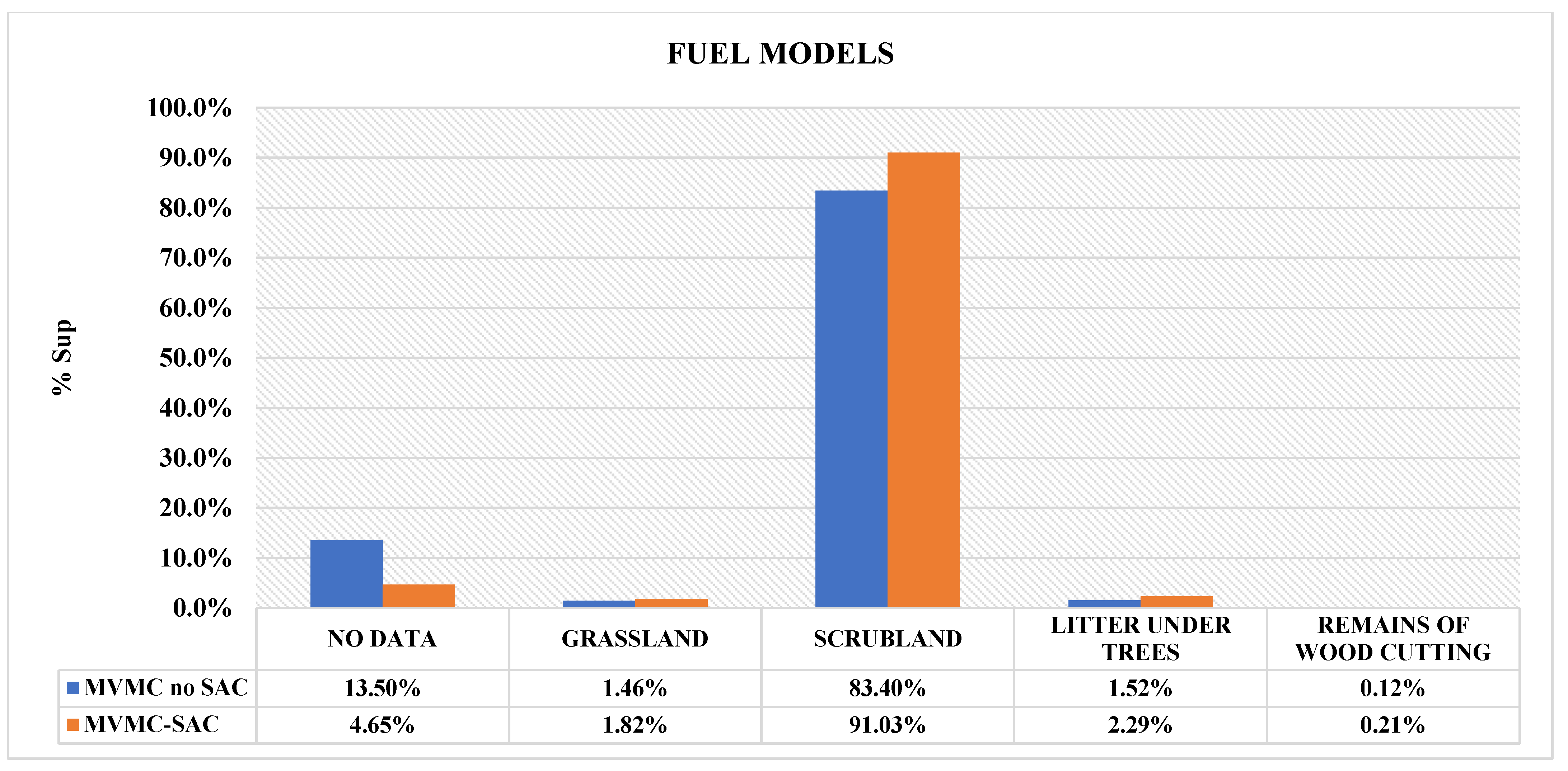

The analysis carried out allowed us to find certain differences in the fire regime of the SACs and the MVMCs. The differences found in the SACs are particularly relevant, as they also affected the area burnt by fire (AB/fire), which increased notably in this territorial unit.

Figure 9 shows the percentages of human-caused forest fires produced in Galicia during the period 1999–2014 for each territorial unit. Although the percentages of human-caused forest fires for each study area were practically identical, it is worth mentioning that these were higher for the MVMC, where up to 91.97% of the fires that occurred between 1999 and 2014 were caused by man or as a result of various acts of negligence. Of the total number of human-caused forest fires in Galicia between 1999 and 2014, 9.95% occurred in SACs.

In SACs, the percentage of human-caused forest fires was 91.14% (

Figure 10). A significant reduction in intentionality (percentage of human-caused forest fires) was also observed after 2005, between 5 and 6 percentage points. However, although the percentages of reduction were very similar, the smallest reduction was found precisely in the SACs where, in addition, the overall reduction in the number of fires was greater than that observed among the intentional fires. Despite the general downward trend, we observed that there was greater intentionality in the SACs.

Regarding the rate of human-caused forest fires before and after 2004 in each territorial unit analysed,

Table 2 shows that the highest rate of wildfires before 2004 was reached by the whole of Galicia (0.52 fires/100 ha), followed by MVMC no SAC (0.51 fires/100 ha). After 2004, the reduction in the intentionality rate was generalized, although higher in MVMC and MVMC no SAC.

After 2004, the rate of forest fires for the different territorial groups analysed tended to converge, with very close values between all of them, such that the SACs did not seem to benefit from the same decrease as the other study groups (

Figure 11).

A more detailed analysis of the obtained results found that the area burned by fire (AB/fire) increased significantly after 2004 in all territorial categories studied. Interestingly, the highest percentage of increase occurred in MVMCs, where the area burned by fire increased by 233.36%, as well as in SACs, where the increase was 232.68% (

Table 3). In these SACs, the area burned by fire was even the largest of all studied categories (

Figure 12). In the MVMC-SAC intersection areas, however, the percentage increase was the smallest, which could indicate that the property regime had some influence on the fire regime.

In relation to the property regime, it should also be noted that the only territorial group in which there was a reduction in the annual burned area between 1999–2014 was the MVMC–SAC (30.96%). This means that, despite the increase in the area burned by forest fire in the analysis period, the reduction in the number of fires compensated for the damage caused by this type of accident, a circumstance that was not found for the remaining groups.

Finally, in order to answer the questions posed above and check if the differences detected were statistically significant, mean comparison analyses were carried out considering homogeneous variances (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). The results are shown and analysed below.

For the analysis of intentionality in SACs (Issue 1), the null hypothesis was rejected both for the rate of forest fires and for the area burned by fire (

Table 4), allowing us to conclude that the differences in existing means were significantly different, although in the opposite direction in both cases. Thus, while there was a significant decrease in the number of fires from 2004 onwards (

Figure 13), the area affected by fire was much higher after that year.

With regard to MVMCs that included SAC (

Figure 14) or with area included within a SAC (Issue 2),

Table 5 shows that there were no significant differences in the area affected by fire after 2004, although there were significant differences in the rate of forest fires. However, this reduction could correspond to the general decrease also observed for Galicia, so it is not firstly attributable to the approval of the autonomous decree regulating these protected areas. It should be remembered that, as seen in

Table 4, in the SACs there were significant differences in the area affected by forest fires, so that difference could correlate to changes in private properties. In other words, if there were significant differences in the SACs and no significant differences in the MVMC-SACs, these differences must be due to the private properties in the SACs.

Finally, with regard to issue 3, the absence of significant differences was observed, both in the rate of forest fires and in the area burned by fire after 2004, for both MVMC-SAC and MVMC no SAC (

Figure 15 and

Table 6). Therefore, the official declaration of the Natura 2000 network does not seem to be decisive in the dynamics of the studied forest fires. This result corroborates what is observed in

Table 5 with respect to the particular properties, since in this case the presence of the SAC did not seem to have any consequence.

To summarise, the results obtained are shown in

Table 7. The decrease in the number of fires was generalised and very important after 2004, so significant differences were expected. However, it is noteworthy that there were significant differences in the area burnt in the SACs (Issue 1).

4. Discussion

According to the results we obtained, it can be seen that the Natura 2000 network did not have a very positive effect on the forest fire regime in the SACs. On the one hand, the percentage of forest fires caused by man decreased less in the SACs (

Figure 10) than in the other territorial units analysed. We also saw that the SACs suffered a significant increase in the area burnt by fire (232.68% for the study period, as shown in

Table 3). Likewise, the SACs did not have the generalized decrease in the number of fires observed for other areas of Galicia. While the rate of fires in the MVMCs decreased very significantly after 2007, the rate in SACs was not as favourable (

Table 2 and

Figure 11). It can be assumed, however, that the fact that the SACs had a smaller decrease in the number of fires than other territorial units may be due to Galicia’s de facto conservation policy, which leads to respect for certain areas of higher ecological value. In reality, the fact that these SACs have a high ecological value is due to the absence of forest fires.

In view of the results obtained, it cannot be exhaustively established that the cause of this unfavourable behaviour was the promulgation of Decree 72/2004, since the explanation could be found in several factors. However, taking into account that more than 90% of forest fires in Galicia are caused by man, these data seem to indicate a certain opposition to the Natura 2000 network, as the scientific literature has stated [

9,

34,

35,

36,

37]. This unfavourable behaviour could also be explained by land abandonment caused by the Natura network; land abandonment increases the available fuel, which favours an increase in the area burned by forest fires [

72]. This issue will be discussed in detail below.

The larger burned area by fire in the SACs may be due to several reasons. On the one hand, it could be due to the fact that SACs are usually further away from means of fire suppression, so the time to reach the fire is longer. Consequently, this longer reaction time leads to a large affected area. On the other hand, this greater burned area could also be due to the incompatibility of certain activities and/or preventive infrastructures against forest fires with the Natura 2000 network [

73], a circumstance that has not yet been adequately addressed by the managers of the Natura 2000 network. In this regard we agree with Foresta et al., 2016 [

73], on the advisability of carrying out various works that allow the reduction of existing fuel, such as clearing and pruning. In any case, although these circumstances could explain the poor results observed for protected areas (SACs), the results obtained seem to indicate the existence of other additional factors. This seems to be indicated by the fact that the increase in the area burnt in the SACs after 2004 was statistically significant, but not in the case of the MVMC-SACs. In fact, the AB/fire after 2004 in the SACs almost doubled the AB/fire of the MVMC-SACs (12.04 ha versus 6.64 ha;

Table 3). Considering that almost 99.5% of the Galician forest is in individual private ownership, it can be concluded that this excess of burned area in SACs mainly affected private estates. The obtained results (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6) confirm this difference in behaviour between individual private properties and collective private properties (MVMCs), since the statistical differences detected in the SACs were not repeated in the MVMC-SACs. This argument is ratified by the fact that the differences found between MVMC-SAC and MVMC-no SAC were not statistically significant, so the declaration of this legal protection did not cause any change for these territorial units.

On the basis of the above, it is necessary to ask whether the statistical differences we detected were due to the property regime. In this sense, Ficko & Boncina (2019) [

74] found that private owners of private forests and those residing in areas with a high proportion of protected forests in Slovenia, with unfavourable physical and socio-economic conditions, were not in favour of greater forest conservation. In a way, if the Natura 2000 network provoked the rejection of the owners of the protected land [

21], it would be reasonable to think that this rejection would be greater when the protected land was in individual private ownership, and not public or joint, since economic bankruptcy would be perceived differently. In this respect, it is worth recalling what Van der Berg & Koole (2006) [

75] stated for the Netherlands, where rural residents showed a clear preference for active nature management, while urban residents, whose economy depended on other factors, considered managed landscapes to be significantly less beautiful than wild landscapes. It is also necessary to recall the arguments of Bhandari & Jianhua (2017) [

76], with whom we agree when they affirmed that the conservation of biodiversity is very difficult if local communities depend on it to meet their needs. We also agree with them when they stated that, for the proper development of strategies that affect the natural environment, it is essential to understand the dependence that local communities have on that natural environment. Therefore, the best conservation outcomes occur when local communities are empowered [

77]. The biggest challenges for the functioning of the Natura 2000 network are indisputably the level and quality of public participation in its implementation and management, the general negative perception of the public regarding it, the lack of flexibility of the responsible authorities and insufficient consideration of the local context [

21]. In this regard, a European Commission report published in 2014 [

78] stated that conflicts may arise between nature conservation and other human activities due to the fact that nature conservation may have important consequences for other land use activities and thus for the landowner and users, who are likely to disagree with these land use changes. Thus, some activities that may be subject to restrictions or regulations are, among others, grazing, mowing, removal of scrub, hunting and fishing [

78].

It is clear, therefore, that avoiding this rejection greatly influences the success of conservation measures, so it is worth considering how best to avoid such rejection. In this sense, authors such as Kamal & Grodzinska-Jurczak (2014) [

79] or Schröter-Schlaack et al. (2014) [

80] have suggested the need to put in place compensatory financial mechanisms to cover the costs that the Natura 2000 network represents for landowners. Others, however, such as Oldekop et al. (2016) [

79], have insisted on the synergy between conservation and socio-economic development linked to the management of areas to be conserved by local communities. In this respect, the adoption of agreements or contracts with landowners/land users would be important. This would be of particular relevance for recurrent measures such as mowing, for example, rather than the application of restrictions or the requirement of administrative licenses [

78].

In accordance with the above, the fact that the Natura 2000 network has not achieved the desired results may not be due to the legislation itself, as stated in a report by the European Commission published in 2016 [

81], but to a poor implementation of it and, more specifically, to the incompatibility of the preventive measures that we pointed out earlier and to the perception that the rural population has of them. As Kati et al. 2015 [

82] said, it may even be due to the lack of will on the part of public administrations to meet the objectives of the Natura network. Be that as it may, the commission’s report stated that up to 80% of respondents belonging to the agricultural and forestry sector thought at the time of polling that the European directives to safeguard biodiversity were not very important.

We do not agree with Moreira et al. (2011) [

83] when they mentioned that the interventions to be carried out in the Natura 2000 network should promote the renaturalisation process, that is, the homeostatic capacity of natural ecosystems and their degree of resilience, because although this is true, it does not seem to be enough. In this regard, we believe that the preventive measures and infrastructures to be developed in the Natura 2000 network should tend to the integral recovery of the rural environment, as well as the recovery of certain traditional forestry practices aimed at, for example, eliminating fuel, and even to the economic use of small masses of hardwoods, because the landowner only considers his land to be valuable if he obtains remuneration from it (financial or otherwise). At this point it is worth recalling the existence of a direct relationship between forest fires and social conflicts [

29,

30,

31], as well as the relationship between ineffective forest policies and forest fires [

32,

33,

34]. This is particularly important in regions such as Galicia, where arson forest fires are very frequent. It should also be remembered that biodiversity protection measures can lead to land abandonment, which can lead to an increase in the number of fires by favouring the growth of available fuel [

35,

36,

37,

38,

41,

42,

43]. In any case, a better understanding of the causes of conflict and respect for the traditional practices of local communities will help the Natura 2000 network be more successful.

5. Conclusions

In view of the various controversies that have accompanied the Natura 2000 network since its creation, as mentioned at the beginning of this article, it was necessary to analyse the result that it has had on the fire regime, since in Galicia, as has been said, most forest fires are human-caused. In this sense, an increase in the number of wildfires occurring in the SACs or an increase in the burnt area could indicate a rejection of the Natura 2000 network. It was also necessary for our study to focus on the MVMCs, due to the great importance of the MVMCs in the forestry sector in Galicia. This allowed us to observe the differences that exist in different types of property.

Once the necessary calculations were made, we found that the answers to the three questions posed, with which we intended to evaluate the effects of the Natura 2000 network on the fire regime, were uneven. However, in terms of the results obtained, it can be said that the declaration of protection has not brought any benefit to the fire regime for the SACs. On the contrary, the significant increase in burned area in these areas seems to indicate a certain rejection of the Natura 2000 network, mainly by privately owned farms and not communal ownerships such as MVMCs. However, this increase may be due to many other causes not analysed in this study. Therefore, future work should focus on the possible relationship between the occurrence of fires and the property regime. The socio-economic conditions of protected areas also need to be considered, since if the population of those areas perceives the Natura 2000 network as a risk to their living conditions, they will hardly accept it.

It is also necessary to analyse whether the criteria used by the Natura 2000 network in its classification are the most appropriate. For example, although Article 2 of the Habitats Directive [

1] states that economic, social and cultural requirements must be taken into account, it should be remembered that socio-economic conditions were not taken into account during the selection process [

78]. Consequently, if the criteria are not appropriate, it is very likely that the result obtained will be very unfavourable or that there will be some social opposition. If the Natura 2000 network areas had been selected on purely environmental criteria, the number of fires would certainly be lower, as shown by official statistics for those SACs that do have outstanding environmental value [

66]. In fact, as mentioned above, the fact that these SACs have a high ecological value is due to the absence of forest fires. However, in most cases the SAC classification seemed to respond only to the legal obligation to reach a sufficient surface area. At the same time, the classification tried to focus on less populated areas, probably in order to obtain less social opposition. This can be seen in

Figure A1 of

Appendix A [

84], where it can be observed that the Natura 2000 network is mainly located in the most depopulated municipalities of Galicia (West Zone) and in those municipalities where there was a greater loss of population between 2001 and 2014. By acting in this way, it is likely that areas that do not have the ecological value necessary to be protected are being protected, while areas of high ecological value remain unprotected. Anyway, we understand that the success of the Natura 2000 network will depend, to a large extent, either on promoting the socio-economic development of the resident population in the protected lands (which would have the detrimental effect of promoting the abandonment of land), or, preferably, on allowing the economic use that has traditionally occurred in the protected lands. It should be recalled in this regard that it has been the local communities who, through sustainable management of resources, have so far conserved these lands [

9]. In any case, the success of the Natura 2000 network will require the observation of environmental and socio-economic factors as well as analysis of the consequences that the implementation and management of this ecological network have for the rural population.