Biocultural Importance of the Chiuri Tree [Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) H. J. Lam] for the Chepang Communities of Central Nepal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

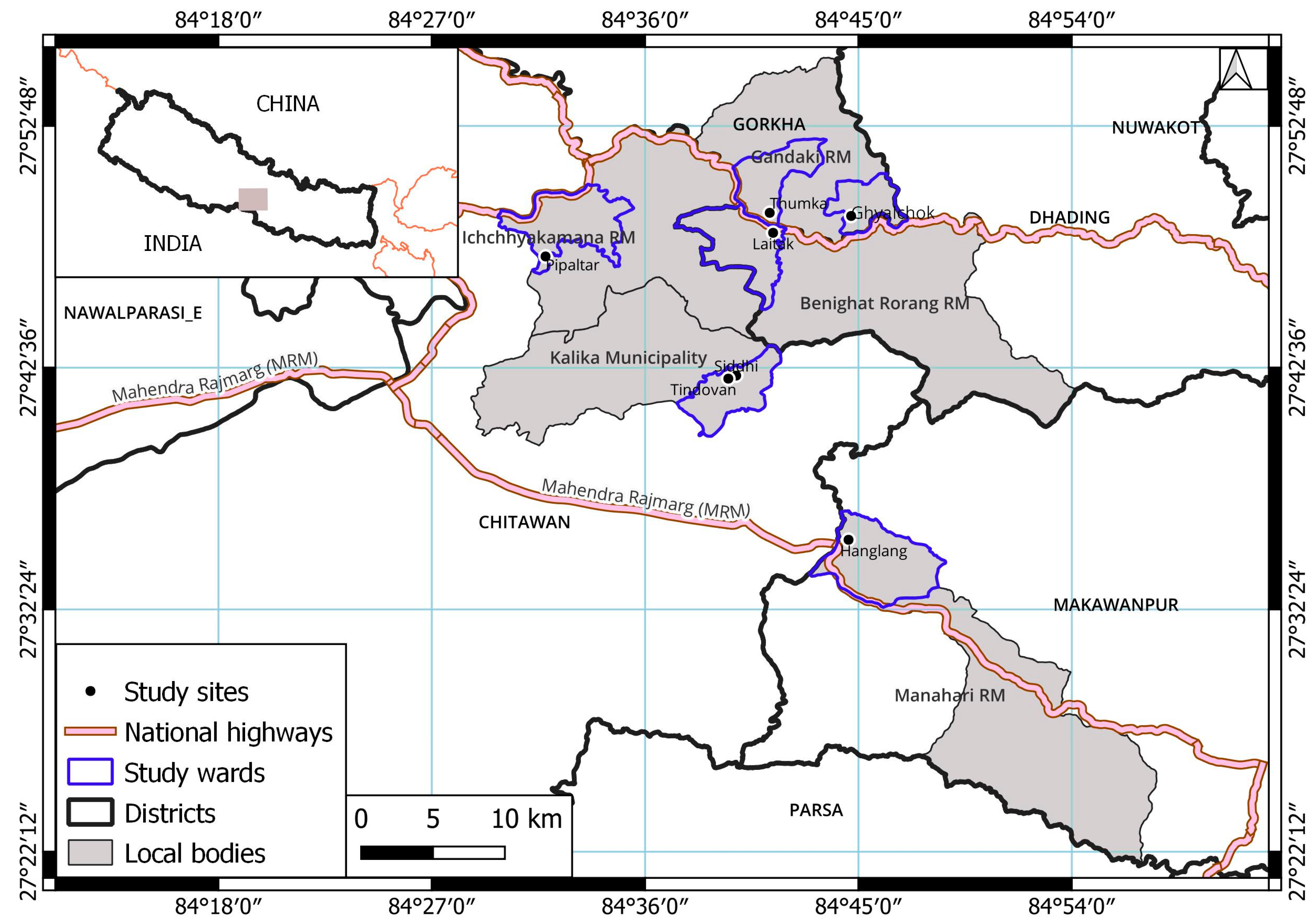

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Chiuri Tree

2.3. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Traditional Uses of Chiuri

3.2. Cultural Importance of Chiuri

“A long time ago there were a father and his son living in the village. A Chinglang (an animal eating humans) once visited the house when the son was alone. The Chinglang wanted to eat his father, but the son was so smart that he was able to make the Chinglang confused about where to search for his father. The son pointed to the South when actually his father had gone to the North to harvest tarul (Dioscorea sp.). One day the Chinglang was tired of searching for the father and thought that the son had lied about his location. The Chinglang went to the direction opposite to that which the son had suggested and caught the father. The Chinglang took the father’s dead body (to the son) and asked if he had anything to say. The son asked for his father’s little finger. As soon as the Chinglang left, the son went to the river bank and planted the finger. The next day he went to the site and saw a big chiuri tree with golden ripen fruits. He knew that Chinglangs would visit the village again to eat people, so he called all the Chinglangs to visit the site where the chiuri tree had grown. He suggested them to taste the fruits. The Chinglangs found them tasty and jumped on the tree. The twigs were set in such a way that when the Chinglangs jumped the twigs broke and all the Chinglangs fell in the river. This is how our existence continues. This was all possible because of chiuri.”

3.3. Trade of Chiuri Products

“We would prepare 50–60 kg of chiuri butter and go to Kathmandu (the capital city of Nepal) by foot. It took 6–7 days to return from Kathmandu. We would make some money and buy sugar, salt, and food sufficient for some months”.

3.4. Ecological Values

3.5. Threats to Chiuri

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide (Translated from Nepali)

- What are the uses of chiuri in your community? (Identify species use values, i.e., intensity, type, and multiplicity of use)

- Characteristics of the species

- Parts used

- Used for

- Methods of use

- Time(s) and method(s) of harvesting

- Areas of collection

- Which groups of the community commonly collect and use chiuri (gender and age)?

- Is chiuri prominently featured in narratives or ceremonies/rituals, dances, songs, or as a major crest, totem, or symbol?

- Does the Chepang language include names and specialized vocabulary about chiuri, including place names, name(s) for the tree itself or some of its parts, names of products created with chiuri, names of ceremonies conducted with chiuri or within forests where it is found, etc.?

- Is chiuri frequently discussed among Chepang people?

- Does chiuri have a story associated with the ancestors? Does it have a spirit of its own?

- Could chiuri be replaced with another available native species that would fulfil the same functions/uses?

- What is the availability (past and present trends) of chiuri?

- Is chiuri sold in markets or exchanged for other products with other groups?

- What other species are dependent on chiuri? (e.g., habitat, food).

References

- Deur, D.; Evanoff, K.; Hebert, J. “Their markers as they go”: Modified trees as waypoints in the Dena’ina cultural landscape, Alaska. Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djoudi, H.; Locatelli, B.; Pehou, C.; Colloff, M.J.; Elias, M.; Gautier, D.; Gorddard, R.; Vinceti, B.; Zida, M. Trees as brokers in social networks: Cascades of rights and benefits from a Cultural Keystone Species. Ambio 2022, 51, 2137–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Tian, L.; Zhou, L.; Jin, C.; Qian, S.; Jim, C.Y.; Lin, D.; Zhao, L.; Minor, J.; Coggins, C.; et al. Local cultural beliefs and practices promote conservation of large old trees in an ethnic minority region in southwestern China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östlund, L.; Zackrisson, O.; Hörnberg, G. Trees on the border between nature and culture: Culturally modified trees in boreal Sweden. Environ. Hist. 2002, 7, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Chinyimba, A.; Hebinck, P.; Shackleton, C.; Kaoma, H. Multiple benefits and values of trees in urban landscapes in two towns in northern South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, J.; Nielsen, J.; Lertzman, K. Using traditional ecological knowledge to understand the diversity and abundance of culturally important trees. J. Ethnobiol. 2021, 41, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouwakinnou, G.N.; Lykke, A.M.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Sinsin, B. Local knowledge, pattern and diversity of use of Sclerocarya birrea. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herrmann, T.M. Indigenous knowledge and management of Araucaria araucana forest in the Chilean Andes: Implications for Native forest conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, L.; Ashby, E.; Waipara, N.; Taua-Gordon, R.; Gordon, A.; Hjelm, F.; Bellgard, S.E.; Bodley, E.; Jesson, L.K. Cross-cultural leadership enables collaborative approaches to management of Kauri dieback in Aotearoa New Zealand. Forests 2021, 12, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uprety, Y.; Asselin, H.; Bergeron, Y. Cultural importance of white pine (Pinus strobus L.) to the Kitcisakik Algonquin community of Western Quebec, Canada. Can. J. For. Res. 2013, 43, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asselin, H. Indigenous forest knowledge. In Routledge Handbook of Forest Ecology; Earthscan; Peh, K., Corlett, R., Bergeron, Y., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 586–596. [Google Scholar]

- Castleden, H.; Garvin, T.; Huu-ay-aht First Nation. “Hishuk Tsawak” (everything is one/connected): A Huu-ay-aht worldview for seeing forestry in British Columbia, Canada. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio 1993, 22, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.F.; Raven, M. Recognising Indigenous customary law of totemic plant species: Challenges and pathways. Geogr. J. 2020, 186, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ens, E.; Reyes-García, V.; Asselin, H.; Hsu, M.; Reimerson, E.; Reihana, K.; Sithole, B.; Shen, X.; Cavanagh, V.; Adams, M. Recognition of indigenous ecological knowledge systems in conservation and their role to narrow the knowledge-implementation gap. In Closing the Knowledge-Implementation Gap in Conservation Science; Ferreira, C., Klütsch, C.F.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 109–139. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, A.; Ormsby, A.A.; Behera, N. A comparative assessment of tree diversity, biomass and biomass carbon stock between a protected area and a sacred forest of Western Odisha, India. Ecoscience 2019, 26, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Ormsby, A.; Behera, N. Diversity, population structure, and regeneration potential of tree species in five sacred forests of western Odisha, India. Ecoscience 2019, 26, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeda, L.T.; Iskandar, E.; Purbatrapsila, A.; Pamungkas, J.; Wirsing, A.; Kyes, R.C. The role of traditional beliefs in conservation of herpetofauna in Banten, Indonesia. Oryx 2016, 50, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Constant, N.L.; Tshisikhawe, M.P. Hierarchies of knowledge: Ethnobotanical knowledge, practices and beliefs of the Vhavenda in South Africa for biodiversity conservation. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E. Is there a future for indigenous and local knowledge? J. Peasant Stud. 2022, 49, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormsby, A. Analysis of local attitudes toward the sacred groves of Meghalaya and Karnataka, India. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Paneque-Gálvez, J.; Luz, A.; Gueze, M.; Macía, M.; Orta-Martínez, M.; Pino, J. Cultural change and traditional ecological knowledge: An empirical analysis from the Tsimane’in the Bolivian Amazon. Hum. Organ. 2014, 73, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pretty, J.; Adams, B.; Berkes, F.; De Athayde, S.F.; Dudley, N.; Hunn, E.; Maffi, L.; Milton, K.; Rapport, D.; Robbins, P.; et al. The intersections of biological diversity and cultural diversity: Towards integration. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Byg, A.; Herslund, L. Socio-economic changes, social capital and implications for climate change in a changing rural Nepal. GeoJournal 2016, 81, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, R.M.; Evans, A.; Mainali, J.; Ansari, A.S.; Rimal, B.; Bussmann, R.W. Change in forest and vegetation cover influencing distribution and uses of plants in the Kailash Sacred Landscape, Nepal. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 1397–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucheli, J.R.; Bohara, A.K.; Villa, K. Paths to development? Rural roads and multidimensional poverty in the hills and plains of Nepal. J. Int. Dev. 2018, 30, 430–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, B.; Race, D. Outmigration and land-use change: A case study from the middle hills of Nepal. Land 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurung, G.M. A note on the religious beliefs and practices among the Chepang of Nepal. Contrib. Nepal. Stud. 1987, 14, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Rijal, A. The chepang and forest conservation in the central mid-hills of Nepal. Biodiversity 2010, 11, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S. The Chepangs, nature and supra-natural belief. Cross Cult. Discourse 2012, 1, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, B.D. Impact of climate change on livelihoods: Adaptations measures of Chepang community. NUTA J. 2018, 5, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piya, L.; Maharjan, K.L.; Joshi, N.P. Forest and Food Security of Indigenous People: A Case of Chepangs in Nepal. J. Int. Dev. Coop. 2011, 17, 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chikanbanjar, R.; Pun, U.; Bhattarai, B.; Kunwar, R.M. Chiuri (Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) HJ Lam): A tree species for improving livelihood of Chepang communities in Makwanpur, Nepal. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Golay, D.K.; Miya, M.S.; Timilsina, S. Chiuri (Aesandra butyracea) and beekeeping for sustainable livelihoods of Chepang community in Raksirang-6, Makawanpur, Nepal. Indones. J. Soc. Environ. Issues 2021, 2, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; Wiersum, K.F. Tenure arrangements and management intensity of Butter tree (Diploknema butyracea) in Makawanpur district, Nepal. Int. For. Rev. 2002, 4, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, A. Surviving on knowledge: Ethnobotany of Chepang community from midhills of Nepal. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2011, 9, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joshi, S.R. Resource Analysis of Chyuri (Aesandra butyracea) in Nepal; Micro-Enterprise Development Programme; UNDP: New York, NY, USA; Ministry of Industry, Government of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, N.C.; Chaudhary, A.; Rawat, G.S. Cheura (Diploknema butyracea) as a livelihood option for forest-dweller tribe (Van-Raji) of Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand, India. ESSENCE Int. J. Environ. Rehab. Conserv. 2018, 9, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.P.; Uprety, Y.; Rimal, S.K. Deforestation in Nepal: Causes, consequences, and responses. In Biological and Environmental Hazards, Risks, and Disasters; Sivanpillai, R., Shroder, J.F., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2016; pp. 335–372. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M.Q.; Bhattarai, T.R.; De Ridder, M.; Beeckman, H. Growth-ring analysis of Diploknema butyracea is a potential tool for revealing Indigenous land use history in the lower Himalayan foothills of Nepal. Forests 2020, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chikanbanjar, R.; Pun, U.K.; Bhattarai, B. Status and types of Chiuri (Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) HJ Lam) owned by Indigenous Chepang communities in Makwanpur, Nepal. For. J. Inst. For. Nepal 2021, 18, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bist, P.R.; Bhatta, K.P. Economic and marketing dynamics of chiuri (Diploknema butyracea): A case of Jajarkot district of Nepal. Nepalese J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 12, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hunn, E. Size as limiting the recognition of biodiversity in folkbiological classifications: One of four factors governing the cultural recognition of biological taxa. In Folkbiology; Medin, D.L., Atran, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ladle, R.J.; Jepson, P.; Correia, R.A.; Malhado, A.C.M. A culturomics approach to quantifying the salience of species on the global internet. Peop. Nat. 2019, 1, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garibaldi, A.; Turner, N. Cultural keystone species: Implications for ecological conservation and restoration. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, M.A.; Gaoue, O.G. Cultural keystone species revisited: Are we asking the right questions? J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristancho, S.; Vining, J. Culturally defined keystone species. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2004, 11, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, M.A.; Gaoue, O.G. Most cultural importance indices do not predict species’ cultural keystone status. Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.R.A.; Tawake, A.; Skewes, T.; Tawake, L.; McGrath, V. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge and fisheries management in the Torres Strait, Australia: The catalytic role of turtles and dugong as cultural keystone species. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wyllie de Echeverria, V.R.; Thornton, T.F. Using traditional ecological knowledge to understand and adapt to climate and biodiversity change on the Pacific Coast of North America. Ambio 2019, 48, 1447–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costanza, K.K.L.; Livingston, W.H.; Kashian, D.M.; Slesak, R.A.; Tardif, J.C.; Dech, J.P.; Diamond, A.K.; Daigle, J.J.; Ranco, D.J.; Neptune, J.S. The precarious state of a cultural keystone species: Tribal and biological assessments of the role and future of black ash. J. For. 2017, 115, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKemey, M.B.; Patterson, M.L.; Rangers, B.; Ens, E.J.; Reid, N.C.H.; Hunter, J.T.; Costello, O.; Ridges, M.; Miller, C. Cross-cultural monitoring of a cultural keystone species informs revival of indigenous burning of country in South-Eastern Australia. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uprety, Y.; Asselin, H.; Bergeron, Y. Preserving ecosystem services on indigenous territory through restoration and management of a cultural keystone species. Forests 2017, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Population Census of Nepal; Central Bureau of Statistics, Government of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gurung, G.M. The Chepangs, a Study in Continuity and Change; Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, Tribhuvan University: Kathmandu, Nepal, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mukul, S.A.; Byg, A. What determines indigenous Chepang farmers’ Swidden land-use decisions in the central hill districts of Nepal? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, K.; Berg, Å.; Ogle, B. Uncultivated plants and livelihood support—A case study from the Chepang people of Nepal. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2009, 7, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manandhar, N.P. Plants and People of Nepal; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, B.; Chikanbanjar, R.; Kunwar, R.M.; Bussmann, R.W.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.Y. Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) H.J. Lam. Sapotaceae. In Ethnobotany of the Himalayas; Kunwar, R.M., Sher, H., Bussmann, R.W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, K.; Datta, B.K.; Shankar, U. Establishing Continuity in Distribution of Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) H.J. Lam in Indian subcontinent. J. Res. Biol. 2012, 2, 660–666. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, T.R.; Adhikari, R.B.; Regmi, G.R. The zigzag trail of symbiosis among Chepang, bat, and butter tree: An analysis on conservation threat in Nepal. In Wild Plants: The Treasure of Natural Healers; Rai, M., Bhattarai, S., Feitosa, C.M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, U.P.; de Lucena, R.F.P.; Lins Neto, E.M.F. Selection of research participants. In Methods and Techniques in Ethnobiology and Ethnoecology; Albuquerque, U.P., da Cunha, L.V.F.C., de Lucena, R.F.P., Alves, R.R.N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, O.; Gentry, A.H. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. Statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Econ. Bot. 1993, 47, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, T. Qualitative Research in Action; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, R.; Zimmermann, H.; Hensen, I.; Mariscal Castro, J.C.; Rist, S. Agroforestry species of the Bolivian Andes: An integrated assessment of ecological, economic and socio-cultural plant values. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 86, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancı, C.; Oruç, S.; Mosulishvili, M.; Wall, J. Cultural keystone species without boundaries: A case study on wild woody plants of transhumant people around the Georgia-Turkey border (Western Lesser Caucasus). J. Ethnobiol. 2021, 41, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunholi, V.P.; Ramos, M.A.; Scariot, A. Availability and use of woody plants in a agrarian reform settlement in the cerrado of the state of Goiás, Brazil. Acta Bot. Bras. 2013, 27, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sop, T.K.; Oldeland, J.; Bognounou, F.; Schmiedel, U.; Thiombiano, A. Ethnobotanical knowledge and valuation of woody plants species: A comparative analysis of three ethnic groups from the sub-Sahel of Burkina Faso. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2012, 14, 627–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, B.; Caballero, J.; Delgado-Salinas, A.; Lira, R. Relationship between use value and ecological importance of floristic resources of seasonally dry tropical forest in the Balsas river basin, México. Econ. Bot. 2013, 67, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, A. Living knowledge of the healing plants: Ethno-phytotherapy in the Chepang communities from the Mid-Hills of Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudley, N.; Higgins-Zogib, L.; Mallarach, J.M.; Mansourian, S. Beyond belief: Linking faiths and protected areas to support biodiversity conservation. In Arguments for Protected Areas: Multiple Benefits for Conservation and Use; Dudley, N., Stolton, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, P.; Singh, D.; Mallik, A.; Nayak, S. Madhuca longifolia (Sapotaceae), a review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Int. J. Biomed. Res. 2012, 3, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acharya, P.R.; Pandey, K. Understanding bats as a host of different viruses and Nepal’s vulnerability on bat viruses. Nepalese J. Zool. 2020, 4, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Openshaw, J.J.; Hegde, S.; Sazzad, H.M.; Khan, S.U.; Hossain, M.J.; Epstein, J.H.; Luby, S.P. Bat hunting and bat–human interactions in Bangladeshi villages: Implications for zoonotic disease transmission and bat conservation. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, A.; Bista, R.; Karki, R.; Shrestha, S.; Uprety, D.; Oh, S.E. Community-based forest management and its role in improving forest conditions in Nepal. Small-Scale For. 2013, 12, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.; Pham, T.T.; Karky, B.; Garcia, C. Role of community and user attributes in collective action: Case study of community-based forest management in Nepal. Forests 2018, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Central Department of Botany (CDB). Study of Non-Timber Forest Products of Chure, Nepal; Tribhuvan University, Central Department of Botany: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Uprety, Y.; Tiwari, A.; Karki, S.; Chaudhary, A.; Yadav, R.K.P.; Giri, S.; Dhakal, M. Characterization of forest ecosystems in the Chure (Siwalik Hills) landscape of Nepal Himalaya and their conservation need. Forests 2023, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Village(s) (District) | Households | Distance from National Highway (km) | Walking Time to Nearby Forest (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hanglang (Makwanpur) | 27 | 1 | 5–10 |

| Pipaltar (Chitwan) | 70 | 5 | 5–10 |

| Siddhi and Tindovan (Chitwan) | 404 and 160 | 16 | 5–10 |

| Laitak (Dhading) | <50 | 1 | 5–10 |

| Thumka and Ghyalchok (Gorkha) | 49 and 127 | 1 | 20–30 |

| Criteria Indicating Cultural Keystone Species Status | ICI Rating | Related Question(s) in the Interview Guide |

|---|---|---|

Intensity, type, and multiplicity of use

| 5 5 | Q1 |

Naming and terminology in the language, including use as seasonal or phenological indicators, names of months or seasons, place names

| 5 | Q4 |

Role in narratives, ceremonies, or symbolism

| 5 | Q3–6 |

Persistence and memory of use in relationship to cultural change

| 5 | Q3–6 |

Level of unique position in culture

| 5 | Q7 |

Extent to which it provides opportunities for resource acquisition from beyond the territory.

| 4 | Q9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uprety, Y.; Asselin, H. Biocultural Importance of the Chiuri Tree [Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) H. J. Lam] for the Chepang Communities of Central Nepal. Forests 2023, 14, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030479

Uprety Y, Asselin H. Biocultural Importance of the Chiuri Tree [Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) H. J. Lam] for the Chepang Communities of Central Nepal. Forests. 2023; 14(3):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030479

Chicago/Turabian StyleUprety, Yadav, and Hugo Asselin. 2023. "Biocultural Importance of the Chiuri Tree [Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) H. J. Lam] for the Chepang Communities of Central Nepal" Forests 14, no. 3: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030479

APA StyleUprety, Y., & Asselin, H. (2023). Biocultural Importance of the Chiuri Tree [Diploknema butyracea (Roxb.) H. J. Lam] for the Chepang Communities of Central Nepal. Forests, 14(3), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030479