Abstract

Throughout the long history of urban expansion and development, some of the natural mountains, lakes, and rivers that were once located on the outskirts of a city have gradually been encircled within it and have become nature in the urban, i.e., they are now in the heart of the city. These are not only green infrastructure for contemporary cities; they have also accumulated a rich cultural heritage and are closely related to the physical health and subjective well-being of city dwellers. The objectives of this study were: (1) to identify the no-material services that the public perceives from UGSs throughout history that contribute to subjective well-being; (2) to analyze which landscape elements are associated with the provision of such services and then to clarify the value of UGSs throughout history and provide a theoretical basis for urban managers. We returned to the original concept of cultural services (information services) to understand how UGSs throughout history, as information sources, have provided subjective well-being to specific groups of people. And we build a classification system for information services based on this understanding. Based on existing research methods on cultural services, we found that collecting information carriers such as texts, images, and interview transcripts is a more effective way to identifying the intangible services provided by a landscape than monetary methods. From understanding of the information communication process, we attempted to integrate the supply and demand indicators of information services. We validated the feasibility of the method of information service identification using Yuexiu Hill in Guangzhou, which has a construction history of 2000 years, as an example. Through the word frequency statistics of 1063 ancient poems (a type of information carrier), elements of the historical landscape of Yuexiu Hill and the information services provided in the past were identified. After that, semantic networks were constructed to analyze the association between elements and services. The results of this study show that information service identification is an effective method of analyzing the effect of the promotion of UGSs throughout history on the subjective well-being of the public. The provision of information services depends on the accumulation and dissemination of environmental information; both natural and cultural elements, especially symbolic elements, play an important role in this process.

1. Introduction

The expansion of cities has caused some natural mountain ranges, lakes, and rivers that used to be located on the periphery of cities to be gradually wrapped up in them and become nature in the center of a city [1]. In this study, we focused on the contribution of such urban green spaces (UGSs) to subjective well-being throughout history. UGSs throughout history have accumulated rich and nonrenewable natural and cultural heritage over the long history of urban construction and have even higher potential value in archaeological, esthetic, and ecological terms. They have provided both material and nonmaterial benefits to urban residents over a period of time [2]. Even if some UGSs throughout history have been destroyed through overdevelopment or mismanagement, these invisible urban natures still play a role in promoting the subjective well-being of the city dwellers as a shared cultural memory. Thus, it is necessary to identify the nonmaterial benefits that UGSs throughout history have provided to urban dwellers over the evolution of the cities. Notably, the role of urban green spaces in promoting public health and subjective well-being has received increasing attention in recent studies [3,4,5]. However, the problems of classification and quantitative evaluation have not been fully addressed in these studies [6]. An approach is needed to integrate the relationship between the natural ecological and cultural heritage values of UGSs throughout history and the landscape characteristics, so as to support the strategic urban green space planning.

Through the literature review, we have found that the identification of ecosystem cultural services can be an entry point to address the aforementioned issues. Numerous researches have analyzed some nonmaterial benefits that urban residents derive from urban nature by evaluation of cultural ecosystems services [7,8]. However, the concept and methodology of CES still needs to be constantly improved so that diversified cultural services are more fully considered into landscape planning and design. Early researches did not develop a standard method of identifying CESs. It is because that economic logic based on ES theory [9,10] and conceptual frameworks based on biophysical dimensions [11,12] are not applicable to all types of CESs. An obvious informatization tendency has been shown in relevant research methods of CES in recent years, although the concept of “information” is not directly used. In addition to the widely used interview and questionnaire methods, the document and social-media-based methods have also received increased attention [13]. Photographs [14,15] and comments [16,17] publicly published on online social media platforms, historical sources such as books and poetry [18,19], transcripts of community interviews [20,21], and even the number of occurrences of symbolic species in areas such as advertising and shop names [22] have all been used in CES identification. This is because these information carriers record both landscape characteristics and stakeholder perceptions of information services. Returning to the earlier concept of cultural services (information services) [23] and identifying them through the historical records related to environmental information is a more effective method of studying such nonmaterial services. Moreover, it can be easier to understand the nature of cultural service generation using the concept of Information services.

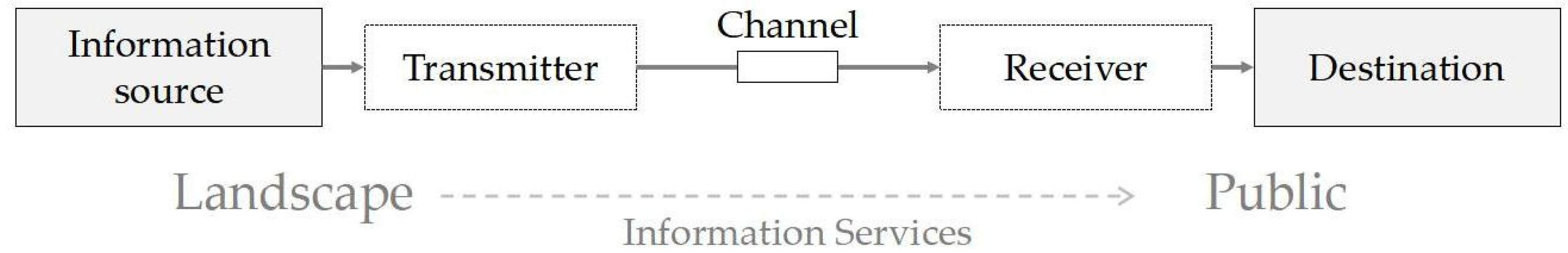

According to Costanza [24], the provision of ecosystem services stems from the flow of materials, energy, and information from natural capital stock, essentially. Capital stock can take intangible forms, notably information stored in computers, individual brains, species, and ecosystems [24]. This environment information including aesthetic information, spiritual and religious information, historic information, cultural and artistic inspiration, scientific information and so on [25]. That composes an information system which contribute to the maintenance of psychological health by providing opportunities for reflection, spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, and aesthetic experience [23]. Claude E. Shannon, the founder of information theory, depicted the general path of information dissemination as a linear model of communication. He believed that communication is the information transmission between two systems: a message is sent by the source, passed through the channel, and then acquired by the host, which constitutes a general communication system (as shown in Figure 1). Shannon stated that an information communication system must contain five basic elements: an information source, a transmitter, a channel, a receiver, and a destination [26]. Essentially, the creation of ecosystem cultural services is a process in which environment information communication occurs between the landscape and the public. Environmental information communication here implies that environmental information stored in the landscape and related social groups (information sources) is received by the public (destinations). The above-mentioned exchange of environmental information occurs more frequently while the public is engaged in cultural activities. These information and activities are recorded in the form of textual or pictorial information and reflect the probability of environment information communication occurring in the landscape. Collecting, encoding, and computing the textual and pictorial information recorded by these carriers can, to some extent, help us understand the potential of UGS throughout history of providing services and public perception of cultural services.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a general communication system [26].

As with other ecosystem services based on the delivery of landscape structure–function–value chains [27], the generation of information services requires public recognition of the value generated by the communication of the relevant information. Due to the considerations of public recognition and demand, seven indicators from the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) that are widely recognized in existing research have been applied [28]. Two of these services have been provided due to UGSs providing places for people to communicate, including: social relations (SR) and recreation and ecotourism (RE). The other five services, including: artistic inspiration (AI), spiritual and religious (S and R), education (E), aesthetic (A), and cultural memory (CM), that have been provided due to UGSs playing the significant part as information source.

In this study, we used Yuexiu Hill in Guangzhou as an example to demonstrate the feasibility of the method of information services identification for analyzing UGSs throughout history. Through the mining of 1063 related ancient poetry texts, we identified the landscape elements of the Yuexiu Hill throughout history and the information services provided in past times. Then, we analyzed the association between them by constructing a semantic network of poetry. In the case study, we tested the following hypotheses: (1) information service is an effective way of identifying the nonmaterial benefits that the public has derived from UGSs throughout history; (2) Historic GUSs are typical examples of the information services provided by the landscape, which benefits from its diverse natural and cultural elements; (3) Evaluating the supply potential and public demand for UGS through history can be an important basis for developing strategic urban green space planning and promoting urban heritage preservation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

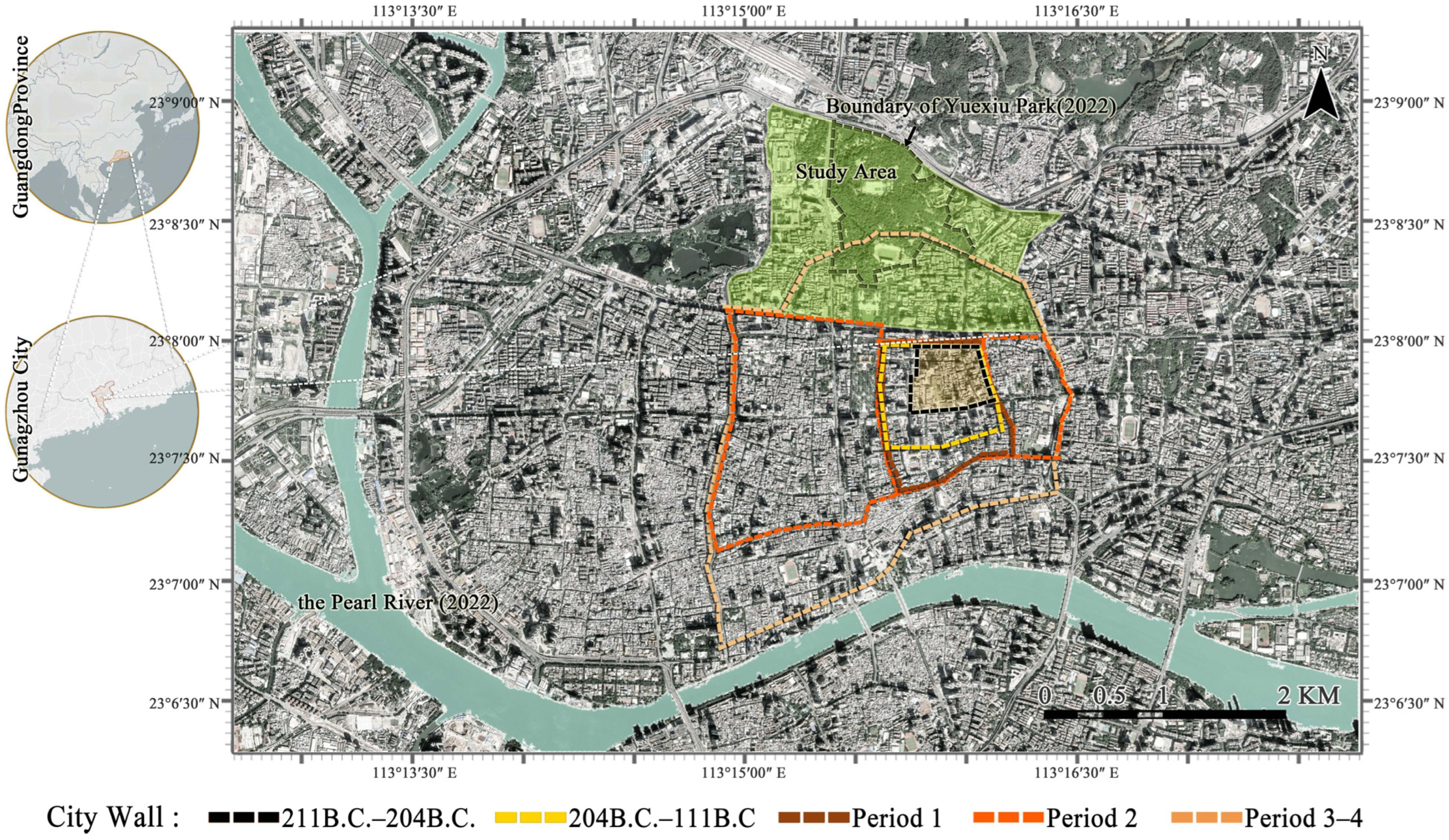

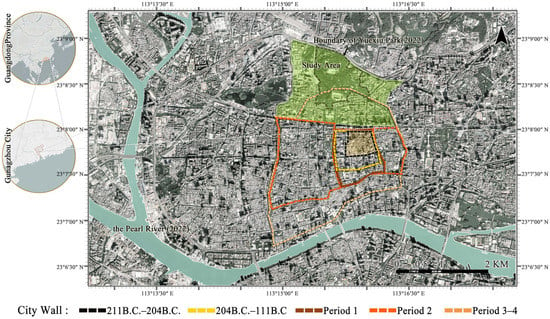

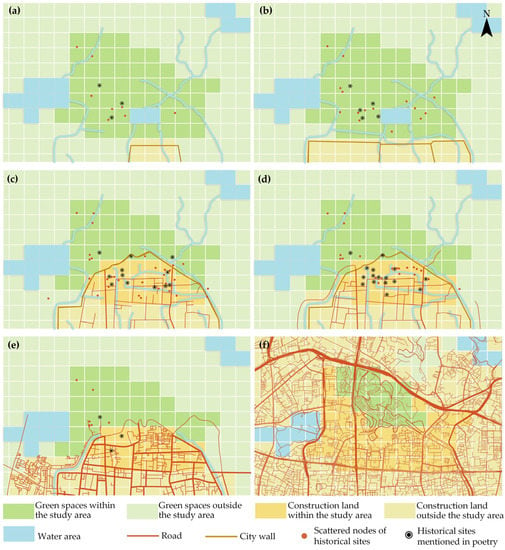

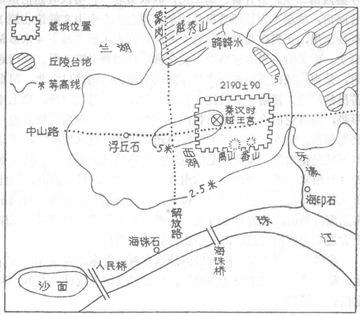

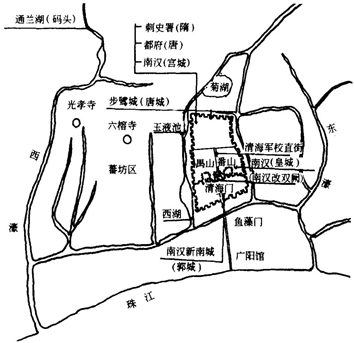

The Yuexiu Hills are a group of natural hills trending northeast–southwest in the northern part of the ancient city of Guangzhou, China. It has a 2000-year history of construction, and the part of the preserved green space is now Yuexiu Park. As their historical boundaries could not be accurately determined, the approximate geographical extent (Figure 2) was mapped based on archaeological information and contemporary road layouts, covering an area of approximately 5110 square meters.

Figure 2.

Map of location and changes in extent of city walls in Guangzhou.

The gradual expansion of the city over a period of more than 2000 years was accompanied by the gradual erosion of the natural environment of Yuexiu Hill. The southern foot of the hill was incorporated into the city walls after the expansion of the city in the Ming Dynasty. The hill became the most representative symbol of the ancient city of Guangzhou during the Qing Dynasty. It has gradually become the core of the city’s cultural activities. Also known as Guangzhou’s dominant hill, which has occupied a central position in the northern part of the city. A description of the corresponding landscape changes in the different historical periods is provided in Table A1. Unlike other urban nature areas in and around the ancient city, the green spaces on Yuexiu Hill area have survived. This is because, in addition to continuing its ecological functions, it has also been preserved as a venue for cultural activities such as festive celebrations, gatherings, and education and is rich in historical and cultural value. This has implications for the public health and subjective well-being of the city’s residents.

2.2. Data Analyses

2.2.1. Database Constructing and Text Data Preprocessing of Yuexiu Hill Poetries

As a literary genre, poetry records rich historical information about cultural activities, landscape elements, and spatial locations. Online databases of poetry provide a description of the content and available data about the year in which the work was published. Conditions are created for accessing local information with a large sample size and a long-time span. Text mining technology is used to obtain valid information from unstructured textual information. The information reflects both the potential of urban green spaces to provide services and the type and extent of information services available to their users.

The poems used in this study were taken from SOU-yun.cn, an online database of 900,000 ancient Chinese poems written over a period of about 2000 years. Names of the historic sites (including their period names) were used for the poetry search. To ensure the integrity of the poem database, the retrieval covered all the names of the historic sites listed in the List of Historic Relics and Sites in the appendix of Millennium Yuexiu Hill [29], compiled by the official Yuexiu Park in Guangzhou. The search yielded 1063 poems composed between 581 and 1949 (last accessed 10 September 2022). The poems were stored in *.txt format, with each poem stored as a separate and continuous paragraph. Then the redundant information was filtered, with only the title and body of each poem stored. From the above process, a database of ancient poems from the Yuexiu Hill was constructed.

Poetry texts needed to be segmented and standardized to improve the accuracy of word frequency analysis and semantic networks. Firstly, the text was pre-segmented using the ROST Content Mining System version 6.0 (a digital humanities-assisted research platform designed and coded by Wuhan University, China). Then, the phrases with the same meaning were grouped together to obtain a standard phrase list of information services and landscape elements (e.g., Table A2 shows 36 groups of standard phrases related to information services and their corresponding original phrases). Using the bulk substitution tool in WPS, all synonyms in the original text were sequentially replaced with standard phrases to obtain a normalized text. Next, the normalized text was again used with the word segmentation tool of the ROST CM version 6.0 to more accurately segment the resulting normalized text.

2.2.2. Analyzing Public Demand: Information Services Identification throughout History of Yuexiu Hill

Poetry records the rich cultural activities of the ancient Yuexiu Hill area. The frequent occurrence of cultural activities related phrases in these poems effectively reflects the public’s demand and approval of the corresponding cultural services. Using the word frequency tool of the ROST CM version 6.0, the number of occurrences of each phrase associated with the information service in the Yuexiu Hill Poetry Database was counted, under the monitoring of the Standard Phrase Table of Information Services (Table A2). From the above phrases, six categories of information services were identified. The sum of the frequency of phrases from the same category reflects the extent to which the public has historically had access to this type of information services provided in the Yuexiu Hill area (Table 1) and can be considered an indication of the demand for information services in the area.

Table 1.

Identification of information services throughout history of Yuexiu Hill area.

2.2.3. Analyzing Services Potential: Landscape Characteristics throughout History of Yuexiu Hill

To determine the esthetic value of an area and its tourism potential, many researchers have assessed landscape characteristics, in addition to aspects such as accessibility and the presence of tourism infrastructure [30,31]. Supply-side CES indicators, contrastingly, are focused on measuring landscape characteristics, as it is from them that CESs are generated [32]. These indicators can identify the space closely related to cultural practices [33], which can be used to indicate the potential of urban green spaces to provide information services.

Along with the construction of the ancient city of Guangzhou over more than 2000 years, the natural basis and historic sites in the Yuexiu Hill area gradually degraded and even disappeared. We have reconstructed the historical landscape characteristics of Yuexiu Hill by text-mining poems and taking historical maps of the Yuexiu Hill area as supporting evidence. Phrases in the poems related to landscape characteristics and elements were identified and classified into three categories, including land cover, natural elements, and cultural elements, covering 2, 4, and 3 subgroups, respectively. The frequency of phrases in the subgroups in each category was separately calculated (Table A3). The results reflected the potential of providing information services in the area.

2.2.4. Connecting Supply and Demand: Constructing the Semantic Network of Poems

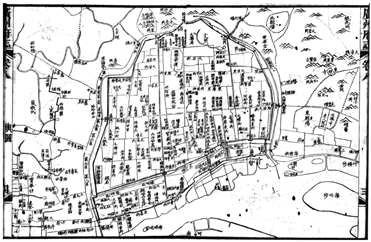

To analyze the associations between various information services and different landscape elements, a semantic network (SN) was constructed based on the retrieved 1063 poems. The SN approach is often used to describe how people understand things in an informative form [33] and has been widely used in studies related to urban design and planning [34,35].

An SN is a graph structure that represents knowledge using nodes and links to express semantic relationships between concepts [36]. Formally, such an object is represented as G = (V, E), where V is the node set, and E is the link set [37]. Each node corresponds to a lexical group, and links between lexical groups are used to indicate the presence of semantic associations between connected nodes. In this study, each node in the semantic network represented an independent and semantically clear phrase in the poetry database. Moreover, the presence of a link between two phrases indicated that they occur in the same poem and that a semantic association exists between the cultural activities and landscape elements they represent. The higher the link weight, the more closely the two nodes are connected, that is, the stronger the association between the service or landscape elements represented by the two phrases. Links between nodes can be represented as a matrix [38].

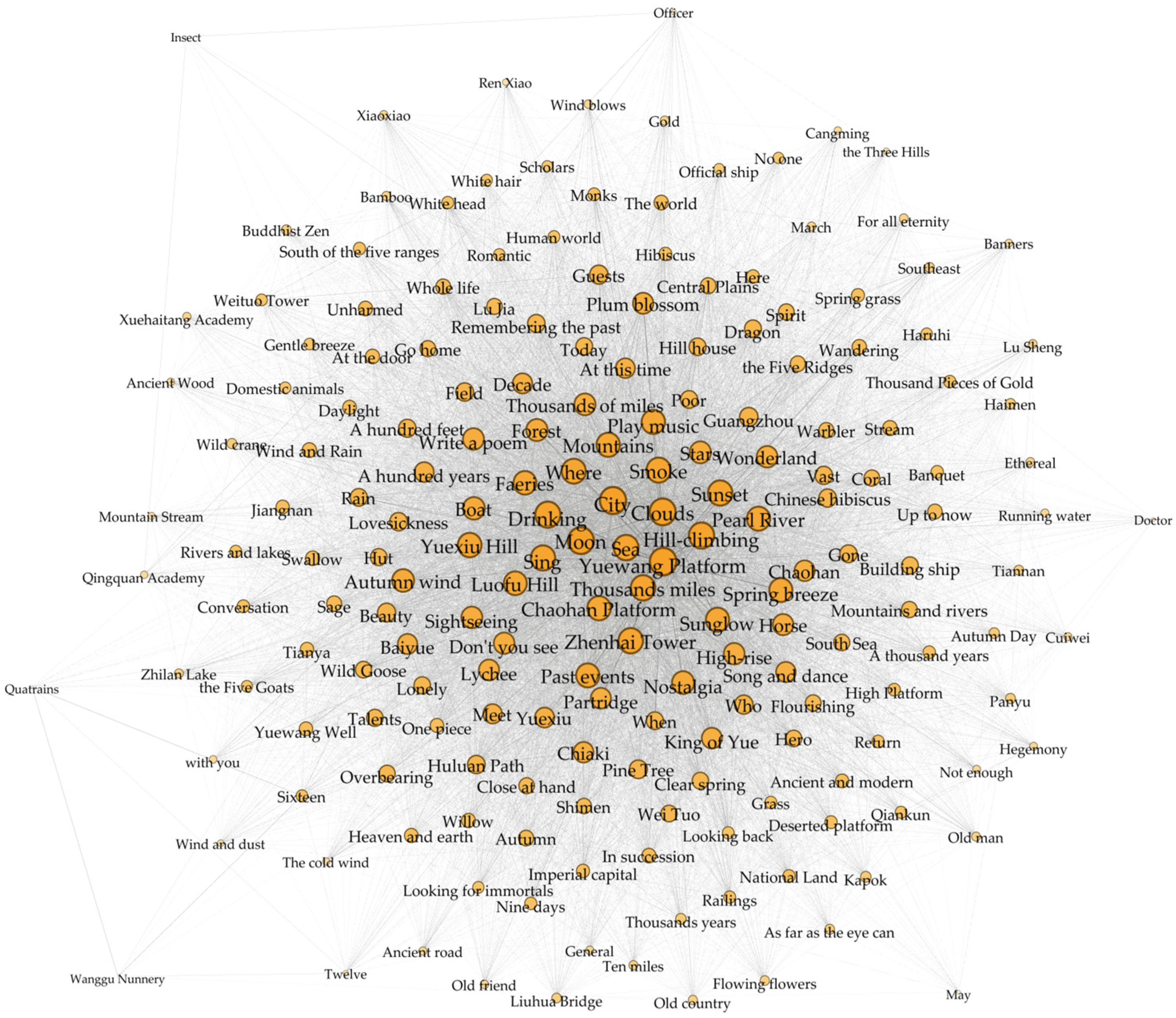

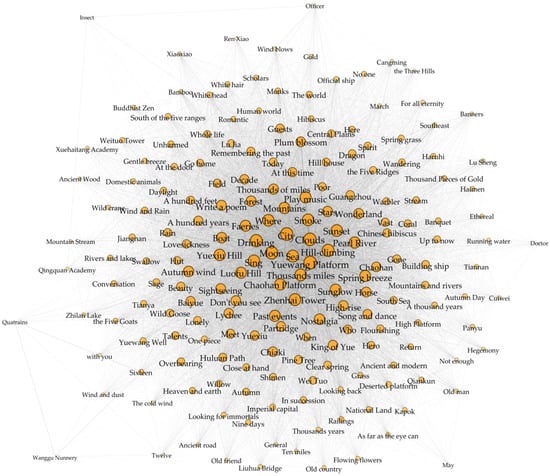

The preprocessed *.txt file was imported into ROST CM 6.0, and we generated a co-occurrence matrix with the Semantic Network Analysis Function. The matrix was stored in a table in *.csv format. Then, a semantic network diagram (Figure 3) was drawn, and the weights of all the links in the network were derived using the complex network analysis software Gephi 0.9.2. To facilitate the comparison of the strength of the association between the six types of information services and the different landscape elements, the link weights of service phrase in the same type (i) corresponding to the element phrase in the same subgroup (j) were separately summed (Wij) (Table A4) and converted to percent (PCTij) for comparison (Table 2).

where i is all phrases corresponding to groups of SR, RE, AI, S and R, E, and CM; j is all phrases corresponding to groups of historic sites, artificial elements, historic figures, natural meteorology, celestial objects, animal species, plant species, waterscape elements, and associated regions.

Figure 3.

Semantic network diagram of Yuexiu Hill poems.

Table 2.

Comparison of link weights between six types of information services and nine subgroups of landscape elements.

3. Results

3.1. Information Services from Yuexiu Hill Perceived by Public throughout History

By summing the frequencies of phrases related to similar information services, we found that the six categories of information services mentioned in the poetry database are not equally distributed in frequency. In descending order, they are: “recreation and eco-tourism” (ISRE = 328), “spirituality and religion” (ISs and R = 225), “cultural memory” (ISCM = 176), “social relationships” (ISSR = 153), “artistic inspiration” (ISAI = 66), and “education” (ISE = 52) (Table 1).

The results of textual information mining reflected the historical public demand for different types of information services provided by urban green spaces. People living in urban areas needed a place for recreation and social interaction, and this was the main reason for the construction of the area over the last two millennia. The activities associated with recreation and ecotourism in the historical Yuexiu Hill area were mainly “hill-climbing” and “singing and dancing”; “banquets” were often held to promote social interaction. Additionally, the public has had opportunities for spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, and esthetic experience during their visits to the urban green spaces. The high frequency of phrases showed that “spiritual and religious” is mainly linked with “Buddhism” and the native “Taoism”; the term “cultural memory” is mainly related to the recollection of historical events that took place in the Yuexiu Hill area; “artistic inspiration” is mainly related to artistic creation activities such as “poetry” and “painting”. “Education” is related to the construction of academies at the southern foot of Yuexiu Hill and the sightseeing activities of scholars (Table 1). The specific activities involved in information services in different areas have differed [39], and the high-frequency phrases in the poems reflect the specific needs of the public for information services in the Yuexiu Hill area.

3.2. Potential of Yuexiu Hill to Provide Information Services throughout History

Three categories of phrases related to landscape characteristics reflect the potential of the historic Yuexiu Hill to provide information services (Table A3).

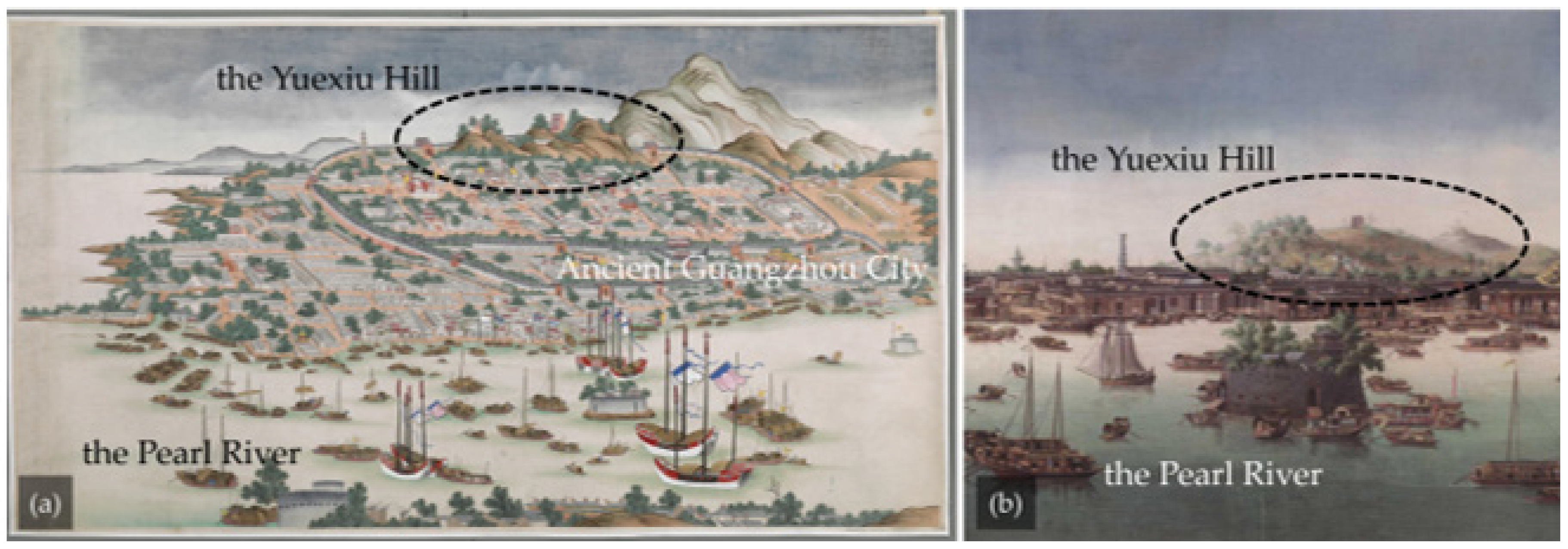

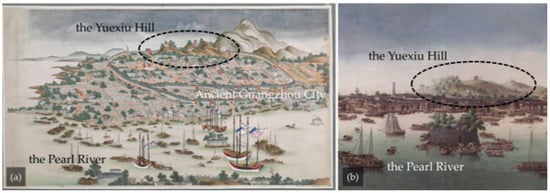

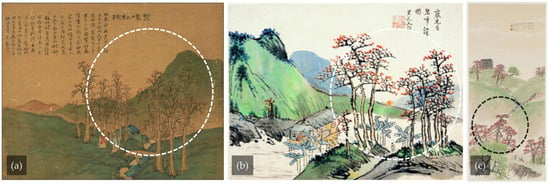

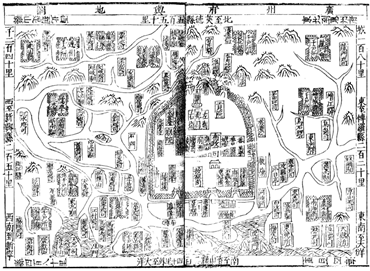

The first category of phrases reflects the richness of land cover types in the historical Yuexiu Hill area and includes two subgroups. We identified eight groups of phrases related to landforms and seven groups of phrases related to natural bodies of water from the poems, which together reflect the diversity of landforms and the level of public interest in each type of landform. Through calculations, we found that vegetated hills were the dominant land cover in the area, with “forest”, “ridge”, and “hill peak” being frequently mentioned, and their word frequency accounting for 19.33%, 12.00%, and 8.95% of the total word frequency in the land cover category, respectively. The words “field”, “cave”, “gully”, “cliff”, and “undulating hills” also appear in the poems. In addition, the high frequencies of “lake”, “spring”, and “stream” reflect the abundance of water in the Yuexiu Hill area, accounting for 13.53%, 11.39%, and 7.02% of the total word frequency in the land cover category, respectively. According to historical records, mountain springs, which converge from Baiyun Mountain in the north to Yuexiu Hill in the south, eventually join the Pearl River in the south, were an important source of water for the ancient city of Guangzhou. In addition to studying the topographical features of the area, the high-frequency references in the poems include the “city (Guangzhou)”, “the Pearl River”, and “the Three Hills”, which can be seen from the high point of Yuexiu Hill, as well as the names of the regions with which the poets associated when they composed their poems, such as “the imperial capital”, “the Central Plains”, and “the Five Ridges”. As seeing in the ancient paintings (Figure 4), emergence of these region names reflects the relevance and integrity of Yuexiu Hill to the surrounding area, both in terms of view lines and public perception.

Figure 4.

Yuexiu Hill in the ancient paintings: (a) View of Guangzhou (Canton) (part of the painting), around 1760–1770, collected by the British Library. (b) Canton harbor and the city of Canton, around 1760, collected by the British Library.

The second group of words reflects the types of natural elements in the Yuexiu Hill area and includes four subgroups: plant species, animal species, natural meteorology, and celestial objects. We found 76 plant names, such as “pine tree”, “bamboo”, “lychee”, and “kapok”. Animals also frequently appear in the poems, including ten mammals, eighteen birds, two amphibians, two fishes, and eleven insects. In addition, climatic elements such as “clouds”, “rain”, and “wind”; and celestial elements such as “sun”, “moon”, and “stars” may also be related to information services.

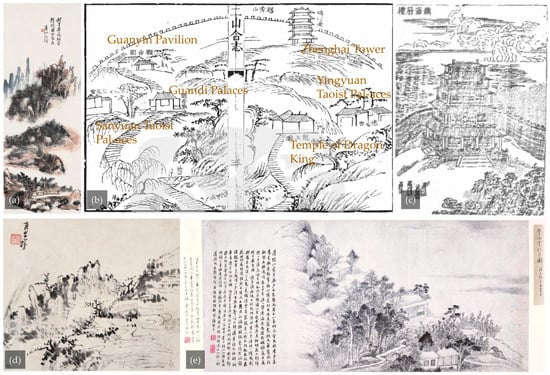

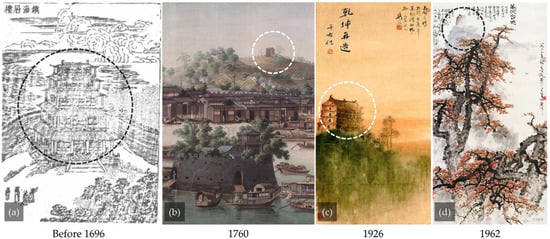

The third category of phrases reflects the types of human elements in the Yuexiu Hill area and includes three subgroups: historic sites, other artificial elements, and historic figures. Over the course of its long history, Yuexiu Hill has not only been a green space for city dwellers to experience nature but also an important place to perceive the city’s history and gain local identity. The 26 historic sites are mentioned several times in the text and are arranged in Table A3 according to when they were built. Among them, “Yuewang Platform”, “Chaohan Platform”, “Yuewang Well”, and “Zhenhai Tower”, which were built in the early period of its history, are more frequently mentioned. The existence of some historic sites can be confirmed in the ancient paintings that have been preserved to this day (Figure 5). In addition to these clearly named historic sites, the poetry database also contains frequent references to human-made elements such as “high buildings”, “high platforms”, “ancient roads”, and “gardens”, as well as historical and mythological figures such as the “King of Yue” and “Lu Jia”.

Figure 5.

Historic sites of Yuexiu Hill in the ancient paintings: (a) Yuewang Platform, Huangbin Hong, 1930s, Collected by the National Art Museum of China. (b) The southern part of Yuexiu Hill in History of the Baiyun Mountain and the Yuexiu Hill, publiced in the Qing Dynasty. (c) The magnificent Zhenhai Tower, before 1696. (d) Hundred step ladders (built on the old site of Huluan Path in 1930), Huangbin Hong, 1930s, Collected by the National Art Museum of China. (e) Appreciating the moon at Xuehai Academy, Chen Pu, 1872, Collected by the Guangzhou Museum of Art.

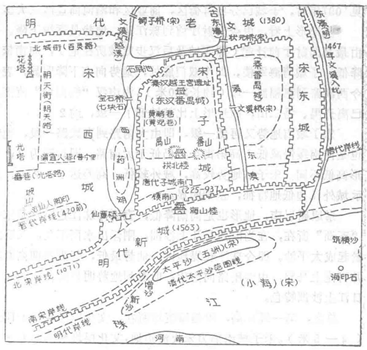

The high frequency of the aforementioned landscape elements in ancient poems implies that there is a connection between these elements and public perception, which is a manifestation of collective consciousness. The existence of these elements brings greater potential for providing cultural services to the landscape. However, the construction of the ancient city was accompanied by the disappearance of the aforementioned landscape elements and the emergence of new ones. These changes have changed the public’s perception and understanding of environmental information. In order to provide a more intuitive expression of the changes in the landscape characteristics of Yuexiu Hill, we use the 250 m × 250 m grid cell as the basic measurement unit, and historical maps collected from different periods are plotted using a unified standard (Table A1), as shown in Figure 6. Then, mark the historic sites mentioned in the archaeological records on the maps. From Figure 5, it can be seen that the spatial connection between Guangzhou City and Yuexiu Hill is becoming increasingly close, and the construction efforts in the southern part of Yuexiu Hill continue to increase, occupying a large amount of original green space and water system space. The human element is constantly being enriched in the region, while, on the contrary, the natural element is being diminished. Of the constantly changing elements of the landscape, which are more closely related to the provision of information services? To answer this question, we further analyze the strength of correlation between landscape elements and information services in the Yuexiu Hill area by building a semantic network.

Figure 6.

Historical mapping evidence for Yuexiu Hill dated (a) The Sui and Tang Dynasties: 581 A.D–959 A.D, (b) The Song and Yuan Dynasties: 960 A.D–1367 A.D, (c) The Ming Dynasties: 1368 A.D–1615 A.D, (d) The Qing Dynasties: 1616 A.D–1911 A.D, (e) The Republic of China: 1912 A.D–1949 A.D, with (f) present situation. (Square grid: 250 m ∗ 250 m).

3.3. Analysis of Relevance of Information Services to Landscape Elements

Landscapes serve an important function for humans, satisfying basic emotional needs such as relaxation, a sense of identity, or a stimulating experience [39]. The correlation between landscape elements in poetry and various types of information services is further verified by the link weights between nodes in the semantic network.

Table A4 shows the link weights between each landscape element appearing in the semantic network (Figure 3) and six types of information services. A higher link weight means that the element is more closely related to the corresponding information service in the table. The statistics in Table 2 show that each type of information service provided is linked to the nine types of landscape elements. The sum of the link weights differs in the links between information services of the same type and the nine subgroups of elements but shows consistency in the links between information services of the six types and the same subgroups of elements. For example, the value of PCTi-association regions, corresponding to the six information services and the association area, ranged from 22.58% to 25.44%; the value of PCTi-animal species, corresponding the six information services and the animal species, ranged from 7.08% to 9.65%. The other seven elements show similar consistency. In terms of facilitating the provision of information services, the nine categories of elements are, in descending order of importance, “associated regions”, “natural meteorology”, “historic sites”, “plant species”, “celestial objects”, “animal species”, “artificial elements”, “waterscape elements”, and “historic figures”. The corresponding PCTj in descending order are: PCTassociated regions = 23.78%, PCTnatural meteorology = 18.66%, PCThistoric sites = 18.17%, PCTplant species = 9.71%, PCTcelestial objects = 8.97%, PCTanimal species = 7.23%, PCTartificial elements = 6.70%, PCTwaterscape elements = 3.54%, and PCThistoric figures = 3.24%. The sum of the link weight between each type of information services and association areas, such as “city (Guangzhou)” and “Pearl River”, is the highest. This reflects that the provision of information services came from the overall context, including the green space itself and the geographical area connected to the surrounding views or with which the public associated. In terms of landscape elements, unlike typical urban green spaces, the Yuexiu Hill area has also been built with a large number of cultural elements, which together play an important role in the provision of information services, in addition to its rich variety of natural elements. In particular, the symbolic historical and cultural landscape elements make the landscape unique. For example, the sum of the linking weights of the six service-related phrases to “Yuewang Platform” is higher than that of the other landscape elements. The names of long-established historic sites such as “Chaohan Platform”, “Huluan Path”, and “Zhenhai Tower” are also connected to a number of service phrases with a high weight (Table A4).

The results of the semantic network analysis also described the degree of correlation between the six types of cultural services identified in this study. In the semantic network, the higher the value of the link weight between two linked phrases, the more frequently they are mentioned in the same poem. We used the link weights between the phrases related to each type of cultural service and the phrases related to other types of cultural services in the form of a matrix, and we summed the weights in the blocks corresponding to the two types of services (Table 3). The six types of services show different degrees of correlation: the darker the area in Table 3, the stronger the connection between the two types of cultural services, and the more likely they are to be offered to the public together. For example, social relationships are associated with five other cultural services in descending order of strength: recreation and ecotourism, spirituality and religion, cultural memory, artistic inspiration, and education. The correlation shows that cultural services are hard to be measured by simple quantification. Therefore, we needed to clarify what simple quantification overlooks to promote an animated discussion based on objective evidence.

Table 3.

Comparison of link weights between each type of information service.

4. Discussion

4.1. Information Services Identification as an Operational Tool

The limitations of early monetary methods have caused progress in CES research to lag behind that on other types of ecosystem services [33]. For this reason, many researchers have suggested promoting increased integration between ES assessment and social science to better understand how which society interacts with ecosystems [40,41]. Some of these researchers have used informatization methods, taking a large collection of textual and pictorial information as a basis for identifying cultural services. Some of these researchers describing and revealing the quantitative characteristics and patterns of change of various services in terms of the frequency of service-related words or images [42,43], i.e., statistical analysis of information to describe and reveal the quantitative characteristics and patterns of change of information. Due to the return to the essence of information interaction between the landscape and the public, information service identification is an effective approach to assess the nonmaterial benefits derived by the public from UGSs throughout history.

This study demonstrates the feasibility of using the information services identification method, selecting the Yuexiu Hill area of Guangzhou as an example. We used 1063 poems composed between 581 and 1949 A.D. as a basis for the identification of information services, and we found that textual information such as poetry contains both descriptions of landscape characteristics and records of cultural activities and even human emotions. From the perspective of information communication, the information recorded in poetry provides data support for the study of the communication process of information from landscape entities to the public. Even from an object perspective, only those characteristics that are considered relevant to the subjective perspective were selected and described when evaluating landscape characteristics, i.e., it reflects the needs and preferences of the people [39]. Therefore, the inaccuracies introduced by the subjective perception of the poetical creator are considered acceptable when reconstructing the characteristics of the historical landscape in this study. In this study, the data obtained from word frequency statistics visually show the intensity of information services were available to the public and the landscape elements that may have contributed to the provision of information services. The semantic network of poems shows the association of various landscape elements with information services. It reveals which types of landscape elements transmit information that plays an important role in promoting subjective well-being. Poetic textual information can be used as an effective basis for information services identification. In addition to the poems, ancient book database and historical map databases [44] can also provide a reliable basis for the identification of historical information services.

4.2. Advantages of Urban Green Spaces throughout History in Information Service Provision

UGSs throughout history have a significant advantage in providing information services compared to general green spaces. This comes from the rich and diverse symbolic landscape elements accumulated in the UGS throughout history. The landscape elements that are information sources carry deeply rooted value systems [40]. Related research suggests that signs, symbols, and written text placed in the public space make up the “discrete construction of space” [45], i.e., the construction of space through semiotic resources [46]. As a source of information, landscape elements carry a deeply rooted value system. Although there are a variety of landscape elements in poetry (Table A3), not all element names appear in the semantic network (Figure 3). In semantic network, landscape elements that are connected with information service phrases and have higher weight are usually more cultural symbolic.

Comparing the word-frequency statistics table with the landscape elements in the semantic network shows that not all the element names in the poems appear in the semantic network. More symbolic elements, including natural ecological elements and historical and cultural elements, are linked to service-related phrases with high link weights. The association of information services with these symbolic elements may stem from a general public recognition of the historical and cultural information they carry.

Natural ecological elements are the main source of information, for most urban green spaces. These elements providing multifaceted environmental information, including esthetic information, spiritual and religious information, and historical information. The information value of natural areas was, and still is, the main reason for the creation of protected areas [25]. Through social and political development over time, plant and animal species have been integrated into human culture in many ways [47] and have a high symbolic value for a particular place [48,49]. For example, the plant most closely associated with recreation and ecotourism, the kapok, is the symbolic tree of Yuexiu Hill and Guangzhou. In ancient times, kapok was widely cultivated on Yuexiu Hill. It became a custom for the people of Guangzhou to enjoy its beauty in spring, and flourished most during the Qing Dynasty. Local painters also produced a large number of paintings depicting kapok in bloom (Figure 7). In the semantic network, links exists between animal elements and phrases corresponding to several information services: “partridge” and “wild goose” usually represent homesickness in Chinese literature. “Crane” is a symbol of the ancient imagination of the fairy world. In terms of botanical elements, “bamboo” and “pine tree” symbolize the pursuit of a noble character; local species such as “kapok” and “lychee” reflect the local identity of the Guangzhou public. In addition, meteorological elements such as “sunglow” and “autumn breeze”, and the names of the celestial elements such as “moon”, “sun”, and “star” are linked to the six categories of information-service-related phrases. As with the flora and fauna elements, the message carried by these landscape elements has been agreed upon by a wide range of social groups, so that the viewer generally has a similar psychological experience when seeing them. Therefore, when managing landscapes and ecosystems, care should be taken to preserve suitable habitats for symbolic species [50] to maintain relevant information services such as cultural memory and artistic inspiration. In addition, there are a large number of animal and plant elements that do not appear in the semantic network, meaning that they do not contribute significantly in conveying cultural information. These non-symbolic species remain an indispensable part of the landscape, whereas the diversity of habitats with species-diverse seminatural environments satisfies the subjective interests of different populations [51,52].

Figure 7.

The kapok tree in the work of a local painter: (a) Li Jian, The Green Mountains and Red Kapoks, the Qing Dynasty, collection of the Guangzhou Art Museum. (b) Xie Lansheng, The Green Mountains and Red Kapoks, the Qing Dynasty, collection of the Guangzhou Art Museum. (c) Chen Shuren, Spring in Lingnan, 1929, collection of the National Art Museum of China.

For UGSs throughout history, historical and cultural elements have also been important information sources for information services, in addition to the aforementioned natural elements. Cultural landscapes have increased potential to provide cultural services than pristine natural ecosystems [33]. The semantic network diagram of Yuexiu Hill poetry (Figure 3) shows that the historic sites have played the role of cultural activity centers. For example, “Yuewang Platform”, “Zhenhai Tower”, “Chao Hantai” and “Hu Ruo”. These historic sites have a high sum of link weights with different cultural service phrases (Table A4). Among them, the Zhenhai Tower has been restored several times, and its site is preserved to this day. While in ancient paintings created during different historical periods, it is always depicted in a prominent position on the Yuexiu Hill as a symbol (Figure 8). In addition, the links between the names of historical figures such as “Wei Tuo (King of Yue)”, “Ren Xia”, and “Lu Jia” are all highly weighted (Table 2). The achievements of these historical figures and their past cultural activities in Yuexiu Hill are a common cultural memory for future generations and are part of the attraction of the area. Our findings reflect the importance of historic sites in urban green spaces, which is consistent with the findings in the literatures [53]. Agimass et al. [54] studied the impact of forest characteristics on recreation and also found that forests with characteristics such as proximity to residential areas and the presence of historic sites were more suitable for recreational use.

Figure 8.

Zhenhai Tower in ancient paintings of different periods of history: (a) The magnificent Zhenhai Tower, Qing Dynasty. (b) Canton harbor and the city of Canton (part of the painting), collected by the British Library. (c) The Zhenhai Tower, Gao Jianfu, collected by the Hong Kong Museum of Art. (d) Spring Dawn in Guangzhou, collected by the Guangzhou Museum of Art.

The uniqueness of UGS in providing information services lies in their rich cultural and heritage value. These historic sites are not only evidence of the information services that people have long-received from urban green spaces, but they have also become symbolic due to the accumulation of cultural constructions and activities throughout history. Carrying rich historical and cultural information, these symbols play an important role in promoting public access to information services the UGSs.

4.3. Artificial Intervention of Urban Green Spaces Information Services Based on the Theory of Information Communication

Artificial intervention from viewpoint of information communication can contribute to sustainability of information services’ provision in urban green spaces throughout history. Charters of the International Council on Archaeological Sites (ICOMOS) stating: “Various heritage protection behaviors are essentially communication behaviors” [55]. The information communication model revealed that the realization of information services is the communication of environmental information from the landscape to the public. The realization of this process depends on the stock of information capital (information source), the needs of the public (destination), and the readability of the information carrier or medium (channel). The transmission of information from the landscape to well-being can be achieved when the information stored in the landscape is required by the public and effectively received. This process can be optimized through human interventions such as the restoration of historical landscape characteristics and the interpretation and presentation of environmental information.

As shown in Table 1, the public demand for different types of information services in the Yuexiu Hill area has widely varied. This deviation in share is influenced by whether the information conveyed by the landscape elements can be accepted and understood by the contemporary public. More attention has been paid to the recreational and ecotourism value of urban green spaces, whereas inspirational enlightenment and educational services that require a clearer understanding of environmental information have received less attention. In addition, the deviation in share is also influenced by factors such as sociodemographic, social, and environmental values as well as the perception of the site and its characteristics by visitors [56]. Different approaches to engaging with nature should be considered in the design of urban environments and urban nature, as well as in integration programs [57].

Abundant natural and cultural information resources have been identified in the historical Yuexiu Hill area, yet the absence of historical information have hindered the transmission of historical environmental information to the public. On the one hand, urban sprawl has changed the land cover and material abundance at the foot of the mountain, which means the change of environmental information. On the other hand, time and changes in the social environment have made it difficult for the public to directly access and understand information related to historical figures and their stories from the place. In this context, interpretation and presentation facilities and activities are needed to convey information about the historical environment to the public across time and space. This will enable the public to better engage in the conservation of natural resources and cultural heritage, understand the symbolic nature of natural and historical cultural elements, and the mechanisms of change. Then gain benefits such as spiritual enrichment, cognitive development and aesthetic experiences.

4.4. New Approach to Support Urban Green Space Strategic Planning for Heritage Preservation, Human Well-Being and Sustainable Development

UGSs throughout history have been witnesses of the continuous subjective well-being of urban dwellers in past dynasties based on nature, and have accumulated rich cultural information. Attitudes to managing nature in the urban environment are changing from the traditional approach of restrictive nature conservation to a balanced approach between use and conservation [58]. Therefore, in the strategic planning of urban green spaces for heritage protection, human welfare and sustainable development, it is necessary to take into account the protection of landscape element entities and related historical information, as well as the needs of the contemporary public. Information service identification based on general communication system theory is an effective way to solve the above problems.

First, the integrated identification of information services in a given area from the point of view of information communication correlates landscape elements with public perception and can provide a quantitative basis for balancing multiple service types and identifying the landscape elements associated with them. The results can guide the classification of needs and priorities for the restoration of landscape elements in historical urban green spaces. This allows for the development of targeted enhancements and the coordination of human and financial investments in strategic green space planning. Second, the method of identifying the information services integrates the joint action of natural and human forces on historic urban green spaces and is an exploration and interpretation of the dual information on natural ecology and cultural heritage. It provides a more systematic knowledge base for the revitalization and regeneration of historic urban areas, based on education about the natural and historic environment, and increases public participation in the decision-making process in the face of environmental conflicts. Third, by presenting the differences in the distribution of hotspots for various types of services, the results of evaluating information services can provide an indication to weigh the construction of green infrastructure satisfying different services. The potential to provide different information services with respect to the landscape characteristics of urban green spaces was explored to better exploit the strengths of the site and compensate for weaknesses in the whole through links with other green spaces. In the case of Yuexiu Hill, for example, which is well-stocked with historical information, the area is more than capable of providing contributions in the areas of spirituality and religion, cultural memory, and education about the historical environment. Recreational and eco-tourism related services, which are subject to conservation management policies, can be provided by other surrounding green spaces.

4.5. Limitations

The use of textual information only as our material poses two limitations for this study: First, we only identified a portion of the types of information services from textual information, for example, esthetic experiences, which are mainly visual information [59], are not represented in this study. The types of information carriers in the database need to be further enriched to more comprehensively identify information services that promote the subjective well-being of the public. Second, the historical Yuexiu Hill landscape reconstructed by semantic network analysis is actually a literary space. The next attempt in this line of research is to further match the spatial information in the historical literature with the real geographical space by combining the research methods used for describing historical landscape characteristics [60,61]. This will lead to more accurate research results in reproducing UGSs throughout history and guide contemporary planning, design, and management.

Using ancient poetry as study material, we analyzed the information services received by the public from the Yuexiu Hill area throughout history. Due to the lack of contemporary public demand identification, identifying contemporary missing historical information service hotspots from comparison with available data was difficult. Therefore, identifying contemporary information services in the Yuexiu Hill area is also the next action plan. By comparing historical and contemporary data, we will determine which historical information services have been perpetuated in contemporary times and what contemporary public needs present new challenges to the preservation and management of the Yuexiu Hill area. The methods of public participation in mapping [7,62,63] and the use of photographs or crowdsourcing of comments [14,17,64] provide a way forward for a contemporary-oriented identification of information services in Yuexiu Hill.

5. Conclusions

Cultural services do not represent a purely ecological phenomenon: they are the result of the complex and dynamic relationships between ecosystems and people [65]. In this study, we returned to an earlier concept of cultural services, “information services”, by using the “general communication system” to understand this complex relationship. Using the Yuexiu Hill area of Guangzhou as an example, we used 1063 poems as a basis to identify the information services provided by this urban green space throughout its history. As an information carrier, poetry provides a record of both landscape characteristics and the creator’s perception of the information service, providing both source and destination analysis data. In turn, text mining methods, such as word frequency statistics and semantic network analysis, provide a method to efficiently process this textual information, which can be replicated in related efforts. Our study verified that information service identification is an effective method to mining the nonmaterial benefits derived from UGSs throughout history by the public. Identifying the information services that UGSs throughout history used to provide to urban residents provides a historical basis for aspects such as cultural heritage preservation and green space management.

The results of the information service identification illustrate the nonmaterial value of historic urban green spaces from the perspective of information communication. The results showed that Yuexiu Hill, in its two thousand years of evolution from a primitive vegetation-covered hill to the urban park it is today, provided ancient city dwellers with a place for ecotourism and social interaction, as well as information services such as cultural memory, spiritual enrichment, artistic inspiration, and environmental education. The results of semantic network analysis revealed a link between information services and the conservation of natural ecological and cultural elements. Among these, symbolic elements have prominently contributed to information services. The accumulation of cultural construction and activities has given Yuexiu Hill and its landscape elements a unique symbolism that carries rich historical and cultural information. This is why this urban green space has remained an attractive and vibrant place throughout its history, playing an important role in promoting subjective well-being.

Efforts will continue to be devoted to the exploration of practical methods to artificially optimize the process of environmental information dissemination. Through planning and design, environmental information has been integrated into the public experience of UGSs throughout history, both on site and online. As such, the conservation of heritage resources should be promoted and the contemporary public demand for information services should be met.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G. and S.W.; methodology, W.G. and S.W.; software, S.W.; validation, S.W. and S.H.; formal analysis, W.G. and S.W.; investigation, S.W. and S.C.; resources, S.W. and S.C.; data curation, S.W. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.G. and S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W.; visualization, S.W. and S.H.; supervision, H.L.; project administration, W.G. and H.L.; funding acquisition, W.G. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province China, grant number 2022A1515011398; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52078222; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 51708227.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Wang Aijun and Huang Haijie of Yuexiu Park for their valuable comments and provision of historical archives.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of the corresponding changes in landscape of Yuexiu Hill for different historical periods.

Table A1.

Description of the corresponding changes in landscape of Yuexiu Hill for different historical periods.

| Name of Dynasty | Number of Poems | Archaeological Maps | Description |

| Time Frame of the Study (581–1949 A.D) | 1077 |  Archaeological site map: location of Yuexiu Hill and ancient city of Nanyue. | The Qin dynasties (beginning in 214 BC) were the beginning of the construction of the ancient city of Guangzhou and the beginning of the construction of Yuexiu Hill by the ancient Guangzhou people. This history laid the foundation for the culture of the Yuexiu Hill: First, the earliest Yuexiu Hill was a place of worship for Nanyue monarchs and ministers; second, Yuexiu Hill was an important water source for the city during the Qin and Han dynasties. Third, Yuexiu Hill was an area for the royal tombs in the Nanyue Kingdom. Since then, Yuexiu Hill has taken on various urban functions and has gradually become an irreplaceable urban heritage composed of multiple values. |

| Sui and Tang Dynasties–Nanhan Dynasties (581–959 A.D) | 30 |  Archaeological site map: location of Yuexiu Hill and ancient city of Tang. | During this period, the spatial extent of Guangzhou City did not remarkably expand, but the functions provided by Yuexiu Hill as a spatial carrier were transformed from their original basis. First, the water system that flows through Yuexiu Hill, in addition to its original function as a water source, was expanded to include navigation and recreational functions. In addition, the construction of religious sites on Yuexiu Hill gradually began during this period. Taoist temples and monasteries such as Yuegang Palaces and Yaoshi Temple were built. During the Nanhan Dynasty, the Yuexiu Hill area was further developed as a royal garden. |

| Song and Yuan Dynasties (960–1367 A.D) | 102 |  Archaeological site map: location of Yuexiu Hill and ancient city of Song. | The city was extensively expanded to the east and west during this period, but the northern side remained at some distance from Yuexiu Hill. No major construction took place on Yuexiu Hill during this period, and only small and medium religious places of worship were built. Located at the southeastern foot of Yuexiu Hill, Lake Ju was a popular scenic spot during the Song Dynasty, and by the Yuan Dynasty, the lake had been filled in to serve as a field. |

| Ming Dynasty (1368–1615 A.D) | 480 |  Map of Guangzhou Prefecture, Jiajing period of the Ming Dynasty | The expansion of Guangzhou to the north during this period incorporated part of Yuexiu Hill into the city and was an important point in the development and construction of Yuexiu Hill. The number and variety of construction activities around Yuexiu Hill rapidly increased during this period. In addition to the existing wells and springs and religious sites, people begun to build private gardens, academies, and military facilities at the foot of Yuexiu Hill. During this period, however, the construction of the city also blocked the Wen River, which used to flow through the city. |

| Qing Dynasty (1616–1911 A.D) | 433 |  Map of Guangzhou Prefecture, Tongzhi period of the Qing Dynasty | During this period, Yuexiu Hill was the most famous scenic spot in Guangzhou and was known as the main hill of the city. The combination of Yuexiu Hill and Zhenhai Tower became an iconic node in the city’s perception of the ancient city of Guangzhou. A number of study halls, religious buildings, and private gardens were built on the site. At the southern foot of the hill, a series of streets and lanes were built. |

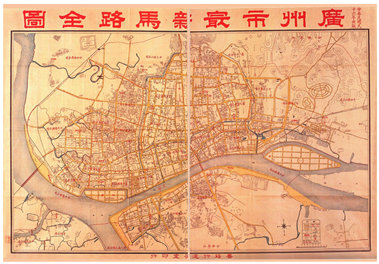

| Republic of China (1912–1949 A.D) | 32 |  Road Map of Guangzhou in the Republic of China, 1927 | During this period, the walls built on Yuexiu Hill were demolished and incorporated into the city; in 1925, part of Yuexiu Hill was turned into a park, and the streets at its southern foot became denser. |

Table A2.

Standard phrases table of information-services-related phrases.

Table A2.

Standard phrases table of information-services-related phrases.

| Classification of Information Services | Standard Phrase | Original Phrase |

| Social relations | Farewell | 送别 别恨 别离 啼别 |

| Have a conversation | 交谈 言笑 谈笑 坐谈 谈天 谈情 高谈 雄谈 谈禅 谈经 闲谈 聊偃 | |

| Banquet | 宴席 满筵 广宴 席间 溪上席 座上宾 雅集 贤人聚 叙群贤 罗群贤 宴坐 列宴 宴列 宴集 宴会 夜宴 携宾 | |

| Drink | 饮酒 壶觞 酒器 螺杯 酌酒 酒酌 酒气 百杯 樽俎 尊罍 樽罍 杯盘 对饮 酒樽 与君醉 三百杯 衔杯 会饮 醉酒 同醉 白酒 载酒 斗酒 杜陵酒 衔杯 酒酣 小酌 清尊 酒盏 酒社 频传斝 酣饮 对酒 | |

| Having tea | 品茶 茶烹 试茗 茶熟 | |

| Recreation and ecotourism | Hill-climbing | 登高 临高 登临 登赏 登坛 登台 登楼 登城 北眺 晚眺 游眺 下瞰 登垄 凭高 吟眺 |

| Go sightseeing | 游赏 行客 旧游 吟赏 踏青 游居 嬉游 交游 卧游 同游 再游 周游 夜游 游北固 胜游 重游 冶游 追游 邀游 漫游 来游 曾游 | |

| Go fishing | 垂钓 钓鳌 钓鱼 钓矶 钓丝 沉钓 钓著 钓竿 钓罢 | |

| Play music | 奏乐 笙歌 击节 乐声 听笙 鼓声 凤凰箫 音乐 奏乐 携琴 箜篌 丝竹 箫鼓 孤笛 听箫 笙箫 鹤笙 鼓瑟 鸣琴 教人唱 歌钟 | |

| Song and dance | 歌舞 妙舞 醉舞 狂歌 朝歌 舞锦绣 歌还舞 舞蛟 娟舞 采衣舞 清歌妙舞 朝歌暮舞 | |

| Artistic inspiration | Poet | 诗人 诗仙 |

| Compose poems | 赋诗 琼瑰 诗文 笔砚 作诗 著稿 写新诗 诗盟 篇诗 词藻 寄吟 读君诗 旧诗社 觞咏 咏溪山 新诗 佳诗 为此诗 赋诗 越台词社 读君诗 一觞一咏 | |

| Paint a picture | 作画 看画 画苑 画图 听禅图 罨画 画阁 | |

| Calligraphy | 书文 著书 敷文 琴书 读书 著稿 笔谈 | |

| Spiritual and religious | Meditation | 参禅 禅关 了悟 三昧 禅味 成佛 禅灯 禅定 佛骨 佛钵 佛灯 佛光 法性禅心 禅关 |

| Monks | 僧侣 僧少 山僧 胡僧 残僧 一个僧 高僧 野僧 为僧 比丘尼 为尼 老尼 禅师 开士 净侣 | |

| Journey to fairyland | 寻仙 仙去 仙游 仙炼 仙仗 迎仙 求仙 仙迹 仙踪 | |

| Wonderland | 仙境 仙乡 仙窟 仙室 仙都 仙已去 仙石 仙树 仙杏 蓬岛 仙岛 仙圃 仙侣 仙宅 仙家 仙城 上方 仙界 玉京 瀛洲 蓬莱 | |

| Fairies | 仙灵 仙翁 仙人 仙子 仙姑 羊石仙踪 五仙 苏仙 歌仙 鹤仙 谪仙 神仙 仙客 五穗仙人 三元大帝 仙羊 北斗 衔穗仙人 五色仙禽 郑仙 | |

| Sages | 圣贤 拜坡仙 鲍姑 苏子 先贤 | |

| Worship | 祭拜 哭祭 祠祀 祠前 | |

| Education | Classical academy | 书院 学堂 讲堂 |

| Academic studies | 致学 还以古籍授 绎史诵经 著书 新学 读书 学文术 论学 劝学 督学 讲学 学业 | |

| Gifted scholar | 人才 群贤 大儒 群英 科名 才子 | |

| Aesthetic | - | - |

| Cultural memory | Nostalgia | 怀古 吊古 凭吊 咏怀 咏史 霸业 |

| Past events | 往事 旧时 千古 当年 兴亡 前朝 回首 昔年 | |

| Festival | 佳节 | |

| Pure Brightness | 清明 | |

| Cold Food Day | 寒食 | |

| The Double Ninth Festival | 重阳 萸囊 菊酒 花糕 萸酒 | |

| The Lantern Festival | 元夕 元宵节 | |

| Worship the kitchen god | 祀灶 | |

| Shangsi Festival | 上巳 祓禊 修禊 | |

| Fly kite | 纸鸢 | |

| Dragon Boat Festival | 端午 端阳 龙舟 |

Table A3.

Phrase frequency table of landscape elements.

Table A3.

Phrase frequency table of landscape elements.

| ID | Phrase | f | ID | Phrase | f | ID | Phrase | f | ID | Phrase | f |

| (I) Land Cover | |||||||||||

| Study area | (8) | Field | 55 | (16) | Range | 12 | (6) | South Sea | 29 | ||

| (1) | Forests | 190 | (9) | Islet | 55 | (17) | Waterfall | 4 | (7) | Central Plains | 28 |

| (2) | Lake | 133 | (10) | Hole | 38 | Associated Regions | (8) | Five Ridges | 25 | ||

| (3) | Ridge | 118 | (11) | Gully | 31 | (1) | City | 112 | (9) | Imperial capital | 22 |

| (4) | Spring | 112 | (12) | Cliff | 22 | (2) | Pearl River | 85 | (10) | Panyu | 17 |

| (5) | Peak | 88 | (13) | Okan | 22 | (3) | Mountains | 44 | (11) | Shimen | 15 |

| (6) | Creek | 69 | (14) | Streams | 17 | (4) | Guangzhou | 42 | (12) | the Three Hills | 13 |

| (7) | Clear spring | 56 | (15) | Pond | 17 | (5) | Sea | 31 | (13) | City of Goats | 12 |

| (II) Natural Ecological Elements | |||||||||||

| Plant species | (34) | Huang Mei | 2 | (1) | Tiger | 40 | (32) | Crab | 3 | ||

| (1) | Plum blossom | 41 | (35) | Orchid | 2 | (2) | Horse | 27 | Fish | ||

| (2) | Pine Tree | 37 | (36) | Brasenia schreberi | 2 | (3) | Domestic animals | 24 | (33) | Carp | 3 |

| (3) | Bamboo | 35 | (37) | Holly | 2 | (4) | Ape | 10 | (34) | Whitebait | 1 |

| (4) | Lychee | 34 | (38) | Bodhi | 2 | (5) | Rabbit | 9 | Insects | ||

| (5) | Kapok | 29 | (39) | Red bayberry | 2 | (6) | Leopard | 5 | (35) | Butterfly | 9 |

| (6) | Willow | 26 | (40) | Frangipani | 2 | (7) | Elk | 3 | (36) | The Cicada | 8 |

| (7) | Hibiscus | 19 | (41) | Sweet-scented osmanthus | 2 | (8) | Rat | 2 | (37) | Silkworm | 6 |

| (8) | Chinese hibiscus | 14 | (42) | Livistona chinensis | 1 | (9) | Wolf | 2 | (38) | Cricket | 2 |

| (9) | Peach blossom | 11 | (43) | Acacia | 1 | (10) | Bat | 1 | (39) | Snail | 1 |

| (10) | Banyan tree | 10 | (44) | Orange Grove | 1 | Birds | (40) | Dragonfly | 1 | ||

| (11) | Maple tree | 10 | (45) | Pawpaw | 1 | (11) | Wild Goose | 57 | (41) | Fireflies | 2 |

| (12) | Calamus | 10 | (46) | Yulan | 1 | (12) | Partridge | 48 | (42) | Spider | 1 |

| (13) | Moss | 10 | (47) | Apricot | 1 | (13) | Warbler | 27 | (43) | Bee | 1 |

| (14) | Chrysanthemum | 9 | (48) | Rattan | 1 | (14) | Swallow | 24 | (44) | Grub | 1 |

| (15) | Lotus | 8 | (49) | Chinese tallow tree | 1 | (15) | Crane | 21 | Natural Meteorology | ||

| (16) | Ficus pumila | 8 | (50) | Elm forest | 1 | (16) | Crow | 12 | (1) | Clouds | 161 |

| (17) | Peaches and plums | 7 | (51) | Coconut | 1 | (17) | Gulls | 11 | (2) | Smoke | 98 |

| (18) | Jasmine | 6 | (52) | Apricot blossom | 1 | (18) | Egret | 7 | (3) | Rain | 68 |

| (19) | Mulan | 5 | (53) | Alfalfa | 1 | (19) | Cuckoo | 9 | (4) | Sunglow | 67 |

| (20) | Betelnut | 5 | (54) | Reed flower | 1 | (20) | Parrot | 4 | (5) | Spring breeze | 56 |

| (21) | Poplar | 5 | (55) | Hemerocallis | 1 | (21) | Petrel | 3 | (6) | Autumn wind | 47 |

| (22) | Nang | 5 | (56) | Toon tree | 1 | (22) | Wild duck | 2 | (7) | Cold wind | 16 |

| (23) | Jasmine | 5 | (57) | Peony | 1 | (23) | Magpie | 2 | (8) | Autumn rain | 12 |

| (24) | Rose | 4 | (58) | Rice | 1 | (24) | Goshawk | 2 | (9) | Spring Rain | 6 |

| (25) | Pear blossom | 4 | (59) | Plantain | 1 | (25) | Oriole | 1 | (10) | Thunderstorm | 6 |

| (26) | Lotus | 4 | (60) | Lagerstroemia indica | 1 | (26) | White pheasant | 1 | (11) | Typhoon | 1 |

| (27) | The locust tree | 4 | (61) | Wisteria | 1 | (27) | Bird of prey | 1 | (12) | Frost and dew | 1 |

| (28) | Rose | 4 | (62) | Phoenix flower | 1 | (28) | Stork | 1 | Celestial objects | ||

| (29) | Flower of Polygonum | 3 | (63) | Cherry | 1 | Amphibians | (1) | Moon | 118 | ||

| (30) | Ficus pumila | 3 | (64) | Pomegranate | 1 | (29) | Crocodile | 3 | (2) | Sunset | 91 |

| (31) | Syzygium jambos | 3 | (65) | Lentinus edodes | 1 | (30) | Frog | 2 | (3) | Stars | 37 |

| (32) | Begonia | 3 | Animal species | Arthropods | (4) | Sunshine | 4 | ||||

| (33) | Red Bean | 2 | Mammals | (31) | Shrimp | 6 | (5) | Solar eclipse | 1 | ||

| (III) Cultural Elements | |||||||||||

| Historic sites | (18) | Taiquan Academy | 1 | (7) | Garden | 20 | (25) | Battery | 1 | ||

| (1) | Yuewang Platform | 433 | (19) | North Garden | 1 | (8) | Vihara | 15 | (26) | Bookstore | 1 |

| (2) | Chaohan Platform | 101 | (20) | Xuehaitang Academy | 12 | (9) | Academies | 13 | (27) | Monk’s house | 1 |

| (3) | Yuewang Well | 54 | (21) | Zhaozhong Ancestral Hall | 8 | (10) | Relic | 12 | Historic figures | ||

| (4) | Yuewang Tomb | 1 | (22) | Yingyuan Academy | 5 | (11) | Palace | 11 | (1) | King of Yue (Wei Tuo) | 101 |

| (5) | Huluan Path | 26 | (23) | Yixiu Garden | 2 | (12) | Ancient Tomb | 9 | (2) | Bao Gu | 38 |

| (6) | Wanggu Nunnery | 17 | (24) | Hongmian Temple | 2 | (13) | Pavilion | 7 | (3) | Lu Jia | 24 |

| (7) | Sanyuan Taoist Palaces | 14 | (25) | Ji Garden | 5 | (14) | Cottage | 6 | (4) | the Five Goats | 23 |

| (8) | Guanyin Pavilion | 7 | (26) | Jupo Academy | 1 | (15) | Battlement | 5 | (5) | Ren Xiao | 13 |

| (9) | Jiao Platform | 4 | (27) | Other Gardens | 16 | (16) | Stone building | 5 | (6) | Jingwei | 5 |

| (10) | Xizhu Temple | 1 | (28) | Other Academies | 11 | (17) | Red chamber | 4 | (7) | Xuan yuan | 5 |

| (11) | Zhenhai Tower | 131 | Artificial elements | (18) | Ancient temple | 4 | (8) | Emperor Wu | 3 | ||

| (12) | Sanjun Ancestral Hall | 8 | (1) | High-rise | 92 | (19) | Road | 3 | (9) | Ruan Ji | 3 |

| (13) | Weituo Tower | 6 | (2) | Hut | 28 | (20) | Red Wall | 3 | (10) | Han Yu | 3 |

| (14) | Xieyan Spring | 2 | (3) | High Platform | 28 | (21) | Ancient well | 3 | (11) | Emperor Qin | 2 |

| (15) | Banshan Pavilion | 2 | (4) | Hill house | 24 | (22) | Circular Mound | 2 | (12) | Jia Yi | 1 |

| (16) | Bushi Nunnery | 2 | (5) | Ancient road | 21 | (23) | Path | 2 | (13) | Diao Chan | 1 |

| (17) | Wanli Bridge | 1 | (6) | Railings | 20 | (24) | Meditation room | 1 | (14) | Emperor Yang | 1 |

Table A4.

Weight of links between service phrases and landscape element phrases.

Table A4.

Weight of links between service phrases and landscape element phrases.

| Historic Sites | Artificial Elements | Historic Figures | Natural Meteorology | Celestial Objects | Animal Species | Plant Species | Waterscape Elements | Associated Regions | ||||||||||

| IS | Elements | w | Elements | w | Elements | w | Elements | w | Elements | w | Elements | w | Elements | w | Elements | w | Elements | w |

| Social relations | Yuewang Platform | 178 | High-rise | 38 | King of Yue | 34 | Clouds | 86 | Moon | 76 | Steed | 26 | Plum blossom | 54 | Clear spring | 18 | City | 66 |

| Chaohan Platform | 56 | Hut | 32 | the Five Goats | 14 | Smoke | 80 | Sunset | 42 | Partridge | 24 | Lychee | 28 | Clear spring | 16 | Sea | 56 | |

| Zhenhai Tower | 48 | Hill house | 20 | Lu Jia | 14 | Sunglow | 44 | Stars | 24 | Warbler | 24 | Willow | 18 | Stream | 16 | Pearl River | 56 | |

| Weituo Tower | 28 | Railings | 12 | Ren Xiao | 10 | Rain | 48 | Sunset | 18 | Dragon | 20 | Bamboo | 18 | Running water | 12 | Luofu Hill | 30 | |

| Yuewang Well | 16 | Ancient road | 8 | Wei Tuo | 6 | Spring breeze | 44 | Wild Goose | 20 | Pine Tree | 16 | Mountain Stream | 6 | Five Ridges | 26 | |||

| Huluan Path | 14 | Deserted platform | 2 | Autumn wind | 32 | Swallow | 16 | Kapok | 6 | Running water | 2 | Imperial capital | 20 | |||||

| Taiquan Academy | 10 | Gentle breeze | 12 | Domestic animals | 10 | Chinese hibiscus | 6 | the Three Hills | 18 | |||||||||

| Xuehaitang Academy | 6 | Cold wind | 12 | Crane | 10 | Hibiscus | 4 | Guangzhou | 18 | |||||||||

| Liuhua Bridge | 4 | The wind blows | 8 | Insect | 8 | South Sea | 18 | |||||||||||

| Central Plains | 18 | |||||||||||||||||

| Baiyue | 10 | |||||||||||||||||

| Panyu | 10 | |||||||||||||||||

| Shimen | 10 | |||||||||||||||||

| WSR-j | 360 | 112 | 78 | 366 | 160 | 158 | 176 | 70 | 472 | |||||||||

| Recreation and ecotourism | Yuewang Platform | 346 | High-rise | 42 | Wei Tuo | 32 | Clouds | 206 | Moon | 152 | Partridge | 60 | Kapok | 74 | Stream | 48 | City | 170 |

| Zhenhai Tower | 162 | Hut | 42 | the Five Goats | 34 | Smoke | 160 | Sunset | 98 | Horse | 56 | Lychee | 62 | Zhilan Lake | 42 | Sea | 146 | |

| Chaohan Platform | 120 | High-rise | 74 | Lu Jia | 18 | Sunglow | 108 | Stars | 64 | Warbler | 44 | Plum blossom | 52 | Clear spring | 32 | Pearl River | 112 | |

| Huluan Path | 68 | Railings | 42 | Ren Xiao | 12 | Rain | 90 | Sunset | 36 | Wild Goose | 36 | Hibiscus | 40 | Mountain Stream | 14 | Luofu Hill | 68 | |

| Xuehaitang Academy | 26 | Ancient road | 34 | King of Yue | 18 | Spring breeze | 76 | Swallow | 34 | Pine Tree | 36 | Running water | 2 | Five Ridges | 60 | |||

| Liuhua Bridge | 26 | Hill house | 32 | Autumn wind | 64 | Dragon | 28 | Willow | 36 | Baiyue | 52 | |||||||

| Yuewang Well | 24 | Deserted platform | 24 | Gentle breeze | 28 | Domestic animals | 22 | Chinese hibiscus | 24 | Central Plains | 42 | |||||||

| Weituo Tower | 20 | High Platform | 22 | Cold wind | 22 | Crane | 20 | Bamboo | 20 | Guangzhou | 40 | |||||||

| Qingquan Academy | 8 | At the door | 8 | The wind blows | 18 | Pine Tree | 14 | Imperial capital | 34 | |||||||||

| Shimen | 28 | |||||||||||||||||

| Panyu | 24 | |||||||||||||||||

| the Three Hills | 16 | |||||||||||||||||

| South Sea | 16 | |||||||||||||||||

| WRE-j | 800 | 338 | 114 | 772 | 350 | 300 | 426 | 138 | 998 | |||||||||

| Artistic inspiration | Yuewang Platform | 54 | High-rise | 12 | King of Yue | 8 | Clouds | 28 | Moon | 32 | Wild Goose | 6 | Lychee | 12 | Clear spring | 6 | City | 20 |

| Zhenhai Tower | 10 | Hut | 6 | Wei Tuo | 2 | Smoke | 22 | Stars | 14 | Partridge | 10 | Chinese hibiscus | 12 | Zhilan Lake | 4 | Pearl River | 18 | |

| Chaohan Platform | 22 | Hill house | 6 | the Five Goats | 8 | Sunglow | 14 | Sunset | 10 | Dragon | 6 | Hibiscus | 10 | Stream | 10 | Sea | 12 | |

| Yuewang Well | 10 | Ancient road | 4 | Liu Jia | 6 | Spring breeze | 14 | Sunset | 4 | Warbler | 2 | Pine Tree | 8 | Mountain Stream | 4 | Shimen | 12 | |

| Huluan Path | 6 | Deserted platform | 2 | Ren Xiao | 4 | Autumn wind | 12 | Horse | 8 | Willow | 4 | Five Ridges | 10 | |||||

| Xuehaitang Academy | 2 | Rain | 16 | Crane | 8 | Plum blossom | 2 | Luofu Hill | 10 | |||||||||

| Weituo Tower | 2 | Gentle breeze | 4 | Domestic animals | 4 | Pearl River | 10 | |||||||||||

| The wind blows | 4 | Swallow | 4 | Baiyue | 10 | |||||||||||||

| Imperial capital | 6 | |||||||||||||||||

| South Sea | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| WAI-j | 106 | 42 | 28 | 114 | 60 | 48 | 58 | 24 | 140 | |||||||||

| Spiritual and religious values | Yuewang Platform | 168 | High-rise | 86 | the Five Goats | 26 | Clouds | 164 | Moon | 116 | Horse | 36 | Lychee | 48 | Clear spring | 42 | Sea | 110 |

| Zhenhai Tower | 84 | Hut | 16 | King of Yue | 16 | Smoke | 86 | Stars | 68 | Dragon | 28 | Plum blossom | 40 | Stream | 26 | City | 86 | |

| Chaohan Platform | 86 | Railings | 16 | Lu Jia | 14 | Sunglow | 72 | Sunset | 58 | Crane | 22 | Chinese hibiscus | 40 | Mountain Stream | 20 | Luofu Hill | 80 | |

| Huluan Path | 24 | Hill house | 12 | King of Yue | 14 | Rain | 68 | Sunset | 20 | Partridge | 20 | Pine Tree | 24 | Zhilan Lake | 16 | Pearl River | 62 | |

| Yuewang Well | 14 | High Platform | 8 | Wei Tuo | 10 | Spring breeze | 36 | Wild Goose | 14 | Bamboo | 14 | Running water | 12 | Five Ridges | 28 | |||

| Liuhua Bridge | 6 | Deserted platform | 8 | Autumn wind | 34 | Warbler | 14 | Willow | 14 | Luofu Hill | 22 | |||||||

| Weituo Tower | 6 | At the door | 2 | Gentle breeze | 12 | Domestic animals | 12 | Kapok | 10 | South of the five ranges | 18 | |||||||

| Wanggu Nunnery | 6 | The wind blows | 8 | Swallow | 8 | Hibiscus | 10 | Shimen | 16 | |||||||||

| Xuehaitang Academy | 4 | Central Plains | 14 | |||||||||||||||

| Weituo Tower | 2 | Baiyue | 12 | |||||||||||||||

| Qingquan Academy | 2 | South Sea | 8 | |||||||||||||||

| Panyu | 6 | |||||||||||||||||

| WS&R-j | 402 | 148 | 80 | 494 | 262 | 154 | 258 | 116 | 592 | |||||||||

| Education | Yuewang Platform | 18 | Hut | 2 | the Five Goats | 4 | Spring breeze | 10 | Moon | 8 | Wild Goose | 8 | Plum blossom | 10 | Zhilan Lake | 6 | Guangzhou | 10 |

| Zhenhai Tower | 4 | High-rise | 2 | King of Yue | 2 | Autumn wind | 6 | Sunset | 4 | Partridge | 8 | Lychee | 4 | Mountain Stream | 4 | City | 8 | |

| Chaohan Platform | 10 | Railings | 2 | Wei Tuo | 2 | Rain | 4 | Stars | 2 | Horse | 2 | Kapok | 4 | Baiyue | 6 | |||

| Yuewang Well | 6 | High Platform | 2 | Clouds | 4 | Swallow | 4 | Chinese hibiscus | 2 | Sea | 4 | |||||||

| Huluan Path | 4 | Ancient road | 2 | Smoke | 4 | Willow | 2 | South Sea | 4 | |||||||||

| Liuhua Bridge | 2 | Central Plains | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Qingquan Academy | 2 | Five Ridges | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Xuehaitang Academy | 6 | Imperial capital | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Weituo Tower | 2 | Shimen | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Pearl River | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Luofu Hill | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| WE-j | 54 | 10 | 8 | 28 | 14 | 22 | 24 | 10 | 58 | |||||||||

| Cultural memory | Yuewang Platform | 196 | High-rise | 30 | King of Yue | 28 | Clouds | 86 | Moon | 66 | Partridge | 36 | Plum blossom | 26 | Clear spring | 10 | Sea | 66 |

| Zhenhai Tower | 36 | Hill house | 22 | Wei Tuo | 18 | Smoke | 76 | Sunset | 66 | Dragon | 20 | Lychee | 22 | Mountain Stream | 10 | City | 64 | |

| Chaohan Platform | 60 | Deserted platform | 22 | Lu Jia | 6 | Spring breeze | 54 | Stars | 34 | Warbler | 22 | Plum blossom | 20 | Clear spring | 8 | Pearl River | 50 | |

| Huluan Path | 22 | Hut | 18 | Ren Xiao | 4 | Sunglow | 40 | Sunset | 6 | Horse | 18 | Hibiscus | 14 | Stream | 8 | Central Plains | 40 | |

| Liuhua Bridge | 16 | High Platform | 8 | the Five Goats | 4 | Autumn wind | 36 | Wild Goose | 18 | Kapok | 10 | Zhilan Lake | 4 | Luofu Hill | 26 | |||

| Yuewang Well | 4 | Railings | 6 | Rain | 44 | Swallow | 14 | Bamboo | 10 | Running water | 4 | Shimen | 24 | |||||

| Wanggu Nunnery | 2 | Ancient road | 4 | Cold wind | 4 | Domestic animals | 6 | Pine Tree | 6 | Five Ridges | 24 | |||||||

| Xuehaitang Academy | 2 | The wind blows | 4 | Wild Goose | 4 | Willow | 4 | Guangzhou | 20 | |||||||||

| Weituo Tower | 2 | Imperial capital | 14 | |||||||||||||||

| Baiyue | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Panyu | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| South Sea | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| WCM-j | 340 | 110 | 60 | 344 | 172 | 138 | 160 | 44 | 438 | |||||||||

| Wj | 2062 | 760 | 368 | 2118 | 1018 | 820 | 1102 | 402 | 2698 | |||||||||

| Wij (weight): sum of the weights of the links between element phrase j and service phrase i. Wj: sum of the weights of the links between element phrase j and all service phrases. (i = SR, RE, AI, S and R, E, and CM; j = historic sites, artificial elements, historic figures, natural meteorology, celestial objects, animal species, plant species, waterscape elements, and associated regions). | ||||||||||||||||||

References

- Wang, X. Ten Points of Advocacies of Urban Nature. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Olivadese, M.; Dindo, M.L. Historic and Contemporary Gardens: A Humanistic Approach to Evaluate Their Role in Enhancing Cultural, Natural and Social Heritage. Land 2022, 11, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, B. Forest Therapy in Germany, Japan, and China: Proposal, Development Status, and Future Prospects. Forests 2022, 13, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Chu, Y.-C.; Kung, P.-C. Taiwan’s Forest from Environmental Protection to Well-Being: The Relationship between Ecosystem Services and Health Promotion. Forests 2022, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard-Poesi, F.; Matos, L.B.S.; Massu, J. Not all types of nature have an equal effect on urban residents’ well-being: A structural equation model approach. Health Place 2022, 74, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Sanchez, M.; Tejedor Cabrera, A.; Gomez del Pulgar, M.L. The potential role of cultural ecosystem services in heritage research through a set of indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, C.F.; Gerstenberg, T.; Plieninger, T.; Schraml, U. Exploring cultural ecosystem service hotspots: Linking multiple urban forest features with public participation mapping data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Van Damme, S.; Uyttenhove, P. A review of empirical studies of cultural ecosystem services in urban green infrastructure. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; de Groot, R.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: From early notions to markets and payment schemes. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C.; Polasky, S.; Goldstein, J.; Kareiva, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Pejchar, L.; Ricketts, T.H.; Salzman, J.; Shallenberger, R. Ecosystem services in decision making: Time to deliver. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]