Abstract

Visits to forests can improve human health and well-being through various mechanisms. They can support the immune system, promote physical activity, and restore stress and attention fatigue. Questions remain about how perceived qualities in forests important to support such salutogenic, i.e., health-promoting, benefits can be represented in forest simulation tools to allow quantitative analyses, e.g., long-term projections or trade-off analyses with other forest functions, such as biodiversity conservation, wood production, etc. Questions also remain about how different forest management regimes might impact such perceived qualities in forests. Here, we defined three types of salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs), referred to as Deep, Spacious, and Mixed forest characteristics, respectively. We did so by using the perceived sensory dimension (PSD) model, which describes and interrelates more fundamental perceived qualities of recreational outdoor environments that are important to support people’s health and well-being. We identified proxy variables for the selected PSD models in boreal forest stands and compared the effect of five different management regimes on both individual PSD models and the derived SFCs when projecting a forest landscape 100 years into the future. Our results suggest combinations of protection (set-aside) and variations of continuous cover forestry as the most promising strategies to achieve these salutogenic properties in the long-term future. Depending on the SFC in focus and the specific management regime used, between 20% and 50% of the landscape could support associated properties in the long term (100 years). This might impact how forests should be managed when salutogenic outcomes are considered alongside, e.g., wood production and other forest contributions.

1. Introduction

Forests cover approximately 215 million ha in Europe (Russian Federation excepted), accounting for 33% of the total land area, with the Scandinavian countries having the largest share [1]. Although 165.9 million ha (77%) of these European forests are used for wood production, forests also have many other important roles, such as constituting key habitats for biodiversity. They also have the potential to support human health and well-being through similar pathways as observed for green areas in general. This includes the reduction of noise and air pollution, climate regulation, promotion of physical activity, facilitation of social cohesion, and restoration of high-stress levels and cognitive fatigue [2,3,4]. Visits to forests specifically have also been linked with beneficial effects on the immune system [5,6] and have been used to successfully treat patients with exhaustion disorder [7]. It has become clear that the structure of forests, as perceived by humans, is important in relation to such health and well-being effects. Sonntag-Öström et al. [8] found that when given the opportunity to choose between different forest settings, exhausted patients selected easily accessible, relatively open, and bright forests, with visible water and/or shelter. These forests could be described as middle-aged pine forests at a lakeside with sparsely standing trees. In contrast, dense forests with poor visibility were not selected by this type of patient. Studies with a focus on the general population have revealed similar preferences in terms of bright forests and low stand density [9,10,11].

However, in contrast to the patients in the study by Sonntag-Öström et al. [8], individuals from the general population often seem to prefer visually diverse forests with varied age structure and tree species composition [10,12,13,14]. However, Filyushkina et al. [13] concluded that most studies on recreational preferences and forest characteristics focus on single stand attributes and highlight that a stand-level analysis may be too simple since most people experience more than one stand when visiting a forest. They asked people to compose their ideal recreational forest by selecting between three types of stands from a catalogue of drawings and found variations between stands to contribute positively to recreational value, in some cases outweighing contributions of variations within a stand. This suggests a need to consider different stand types supporting complementary recreational needs, which we attempted to do in our present study. Similarly, a recent study among recreationists in a Swedish forested landscape identified a division between two major types of recreational orientation, one more directed towards restorative experiences in solitude and the other more directed towards social activities. Each orientation was associated with different perceived qualities in the environment, again emphasising the need for variation of recreational qualities in the landscape to meet different needs in the population [15].

Given the slow growth of forests, management interventions can have long-lasting consequences on forest structural properties, in turn affecting perceived qualities of importance to support health and well-being outcomes. Although many studies have investigated how different forest structures might affect such perceived qualities, little attention has been given to how specific forest management regimes might directly affect salutogenic, i.e., health-promoting, properties.

1.1. Salutogenic Pathways

The salutogenic health model [16] focuses on factors that promote a state of health and well-being, as opposed to a pathogenic approach focused on factors causing disease or illness. Internal or external stressors push an individual towards disease/illness while salutogenic factors support health and well-being by strengthening the individual’s sense of meaning and coherence in life [16,17]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the broad health and well-being benefits reported from recreation in green areas and natural environments, such as forests, might be understood along three main complementary pathways: (1) mitigation (“reduction of harm”, e.g., reducing exposure to air pollution, noise and heat, etc.), (2) restoration (“restoring capacities”, e.g., attention restoration, physiological stress recovery, etc.), and (3) instoration (“building capacities”, e.g., encouraging physical activity, facilitating social cohesion, etc.) [18]. While mitigating strategies resemble a pathogenic approach, focused on reducing harm, restoration and instoration might be considered salutogenic pathways, dependent on perceived qualities in the environment and psychologically mediated mechanisms [19].

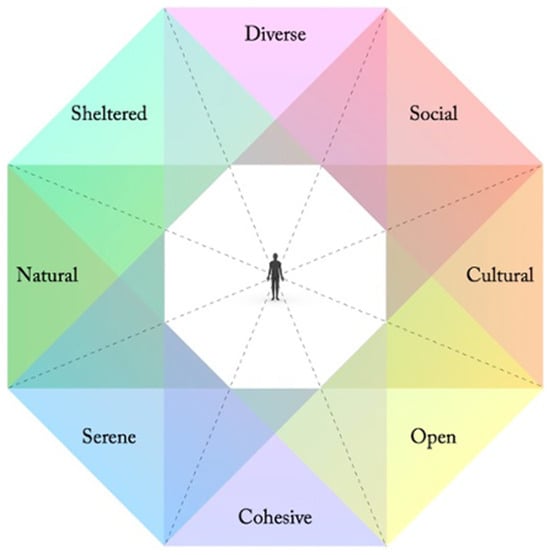

1.2. Perceived Sensory Dimensions

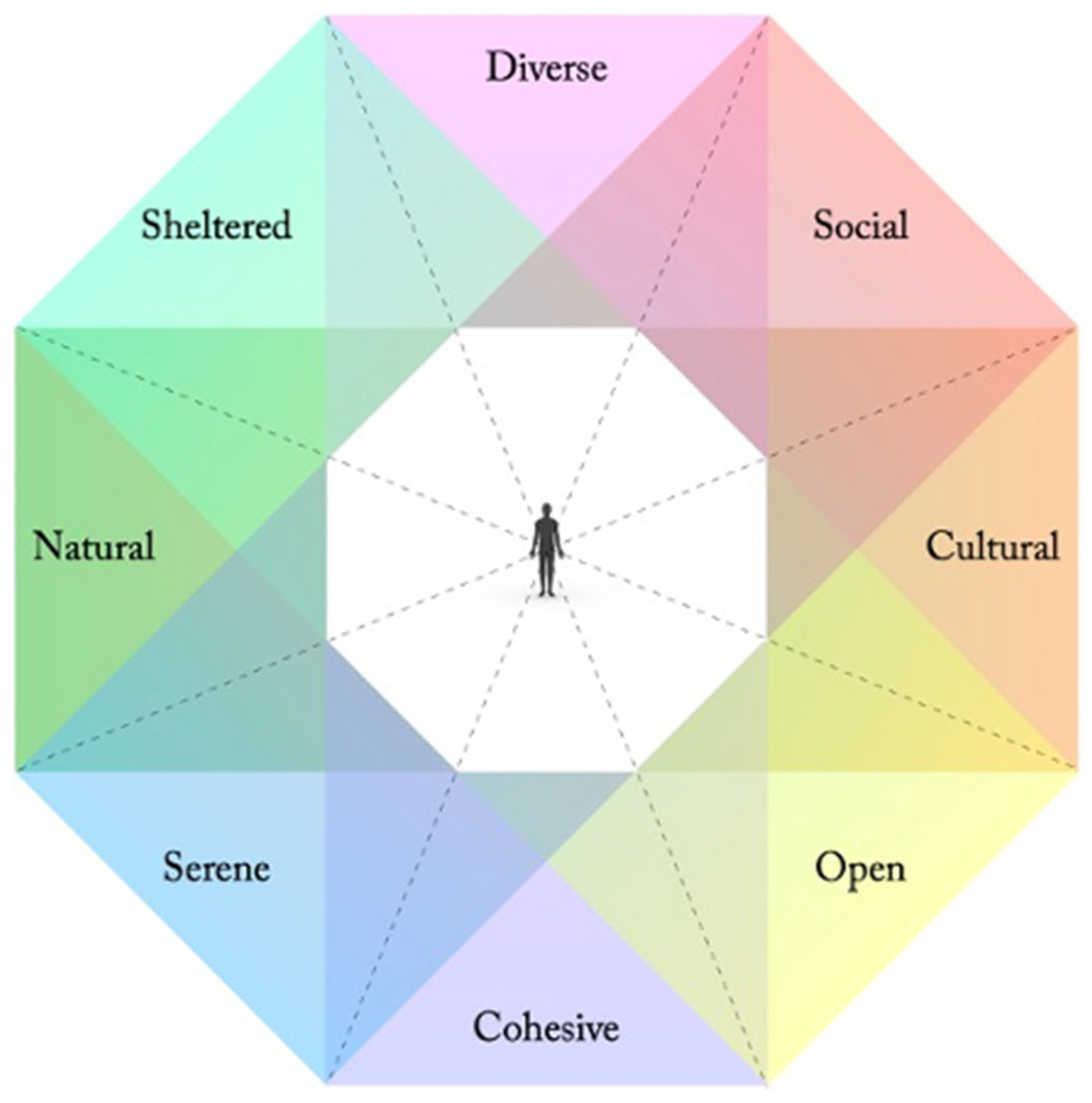

Stoltz and Grahn [20] propose a model (Figure 1) focused on the perceived qualities of outdoor environments. It consists of eight qualities, or perceived sensory dimensions (PSDs) [21]: Natural, Cultural, Cohesive, Diverse, Sheltered, Open, Serene, and Social. These have been suggested to support complementary recreational needs, which is important for both restorative and instorative salutogenic effects. Different versions of the PSDs have been investigated in more than sixty studies worldwide, and results suggest their relevance across cultural contexts [20]. They have been analysed and evaluated in both urban and rural settings [22,23], in rehabilitation gardens [19,24], and—to some extent—in forest environments [25,26,27]. Whereas all eight qualities might support instorative mechanisms [23,28], five of the PSDs have also been specifically associated with restorative effects. In particular Sheltered, Cohesive, Natural, and Serene, but also to some extent the Diverse PSD [19,29]. In the present study, we focused on these five qualities from a forest perspective and investigated how they might be operationalised and combined to predict the future salutogenic development of forest stands under different management regimes to support complementary recreational needs.

Figure 1.

Eight perceived sensory dimensions (PSDs) along four axes of opposing qualities [20]. Adjacent qualities often reinforce each other, while features supporting a specific quality often weaken or contradict the opposite quality.

1.3. Study Aims

The overall aim of our study was to investigate how complementary salutogenic properties of forest stands could change in the long term under different forest management regimes. This investigation was made by interpreting the PSD model in a forest context and, further, representing it in a forest simulation tool. Our main research questions were:

- How can the PSD model be interpreted and implemented in a forest context to support complementary recreational needs?

- Which forest stand variables could represent each PSD at a forest stand level?

- How could individual PSDs and meaningful combinations of PSDs develop in the coming 100 years under different forest management regimes?

2. Materials and Methods

To estimate the salutogenic properties of forest stands, we employed the perceived sensory dimension (PSD) model [20]. We derived three salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs) based on combinations of five PSDs associated with both instorative and restorative mechanisms, i.e., the Cohesive, Serene, Natural, Sheltered, and Diverse qualities. Stand-level structural variables were identified for each of these PSDs and implemented in a forest simulation tool. We then investigated how each PSD and SFC (PSD combination) would develop into the future (100 years), comparing the effects of five different forest management strategies.

2.1. The Perceived Sensory Dimension (PSD) Model

The eight perceived qualities of the PSD model are described as pairs of complementary qualities, along Natural–Cultural, Cohesive–Diverse, Sheltered–Open, and Serene–Social axes, respectively [20]. These axes are interrelated in the model; therefore, they reflect a closer association between more adjacent qualities (Figure 1). It is suggested that adjacent qualities in this model share associations and can be considered synergistic to some extent, whereas opposite qualities might be more difficult to combine at a given site without trade-offs between perceived qualities (ibid.).

2.2. Operationalising the Perceived Sensory Dimensions

To represent the PSDs in our forest simulation tool (see Section 2.4 below for more details on this tool), suitable variables and parameter values for each included PSD were identified. We used the qualitative descriptions of the PSDs provided by Stoltz and Grahn [20] to link with the forest structure variables available in our simulation tool (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected variables and parameter values to represent the included PSDs in our forest simulations.

The Natural PSD is associated with undisturbed natural development and the passage of time [20]. Thus, possible variables could relate to, e.g., the number of old trees, average tree age, self-sown tree growth pattern (i.e., no straight lines with planted trees), age variance (i.e., not homogenous age throughout the stand), time passed since last cutting or thinning, etc. It has been associated with mean stand age in an empirical study in Swedish forests [26]. For this application, we identified stands that have a volume-weighted average age of above 80 years to indicate this PSD.

The Serene PSD describes environments free from disturbances and with few other people [20]. Average noise levels, together with some estimate of visitor frequency, could thus be suitable indicators. As direct values of these variables are not possible to simulate, we used the distance to the nearest roads as a proxy for this PSD. As our threshold for serenity, we followed noise guidelines from an influential report published by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, which recommends a maximum of 45 dBA as a benchmark for forests and recreation areas in proximity to urban developments [30], in line with similar recommendations from the World Health Organisation [31]. We estimated the distance to roads to achieve this threshold using algorithms from the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency [32] implemented in the Nordic Road Noise application (version 1.1, 2014). This suggested a minimum distance of 400 m from the closest road (with an estimated average speed of 70 km/h on hard roads and no heavy traffic) for a maximum noise level of 45 dBA in the stand. This quality was thus unaffected by the type of forest management performed in our scenarios. It is also worth noting that this model did not consider the noise-reducing capacity of the forest structure itself. However, since the PSD rather describes a general lack of all kinds of disturbances, including other people and visual disturbances (e.g., litter, technical installations, or leftover branches/twigs from forestry logging, etc.), we believe that our selected distance-to-road indicator captures some such aspects as well and would give a good overall estimate of this perceived quality.

The Sheltered PSD describes an environment offering a sense of shelter and protection, where one can hide and “disappear” in the environment; “to see without being seen” is a typical need expressed by many stressed people and associated with this perceived quality [19,24]. This PSD might thus be quantified using measures of the amount of vegetation in the height span of humans and its density. Here, we chose 500–2000 tree stems per hectare, above 1.3 m but below 5 m in height, to indicate this PSD (Table 1). This presumably allows for the capturing of forests, providing sufficient horizontal cover at the scale of a human individual.

The Cohesive PSD is closely associated with the size and shape of an area [20]. The bigger the better, and circular rather than elongated or scattered stand shapes, together with a uniform and not too dense vegetation structure (horizontal openness), appear as good indicators (ibid.). Here, we chose stands larger than 2 hectares with less than 500 tree stems per hectare and above 1.3 m but below 5 m in height to indicate this PSD (Table 1). This condition presumably captures stands offering good horizontal visibility and mobility together with extended areas of homogeneous vegetation to offer a sense of a “world in itself” that is possible to explore and wander around within [20].

The Diverse PSD is associated with perceived biodiversity (variation of plants and animals) as well as structural variation and multi-layered vegetation [20]. In a forest context, potential indicators could then include the number of tree species present in the area, as well as varied density and tree age. To fulfil this PSD, in our simulations, we required the stand to have 3 or more vegetation layers, 2 or more tree species, and that the dominant tree species represent less than 70% of the total volume.

2.3. Salutogenic Forest Characteristics (SFC)

Stoltz and Grahn [20] proposed combinations of up to three adjacent PSDs as an efficient way to achieve high salutogenic potential while maintaining low conflict between perceived qualities. Here, we used this proposal to derive three salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs) by combining qualities adjacent to the Natural quality in the PSD model (Figure 1), defined as (i) Deep forest (Natural–Serene–Sheltered), (ii) Spacious forest (Natural–Serene–Cohesive), and (iii) Mixed forest (Natural–Sheltered–Diverse). These combinations of presumably synergistic PSDs contain qualities associated with both restorative and instorative effects [19,23] and seem relatively easy to interpret in a forest context and represent through typical forest structure parameters. They each correspond to specific experience characteristics, outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary descriptions of the three salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs) employed in the simulations.

Individual SFCs can be modelled as the conjunctive values of the specific PSDs. This means that all the specific PSD criteria that were identified for the SFC must be present, otherwise it does not fulfil the conditions for the SFC to be realised. From a mathematical sense, the selected SFC can be evaluated using the following equation:

where , representing the specific PSD p for s stand from the set of stands in the landscape (S), and is the set of PSDs for the specific salutogenic forest characteristic x. The rules used to represent are described in Table 1, while the sets of PSDs for each SFC are found in Table 2.

2.4. Forest Simulation and Management Regimes

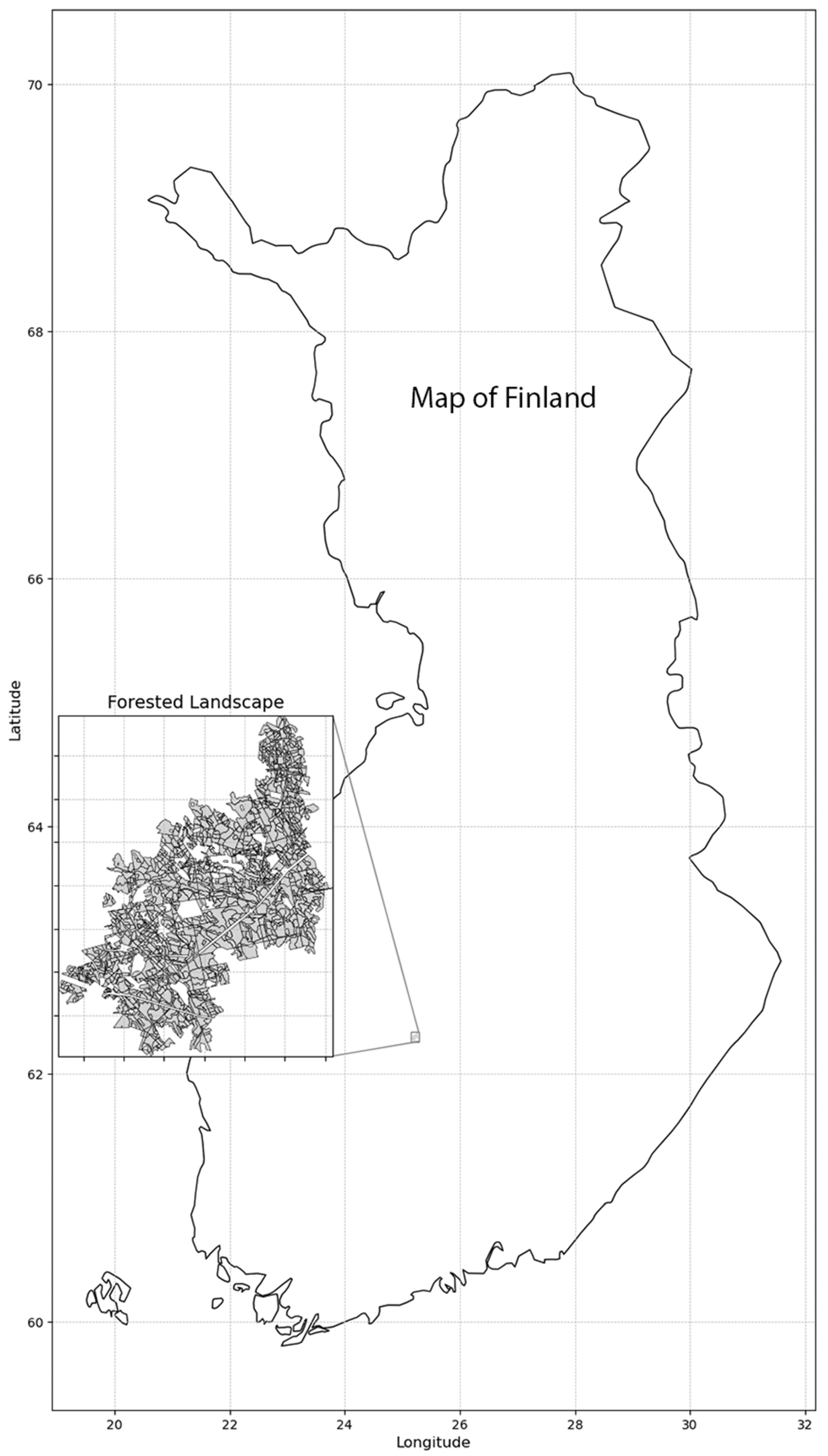

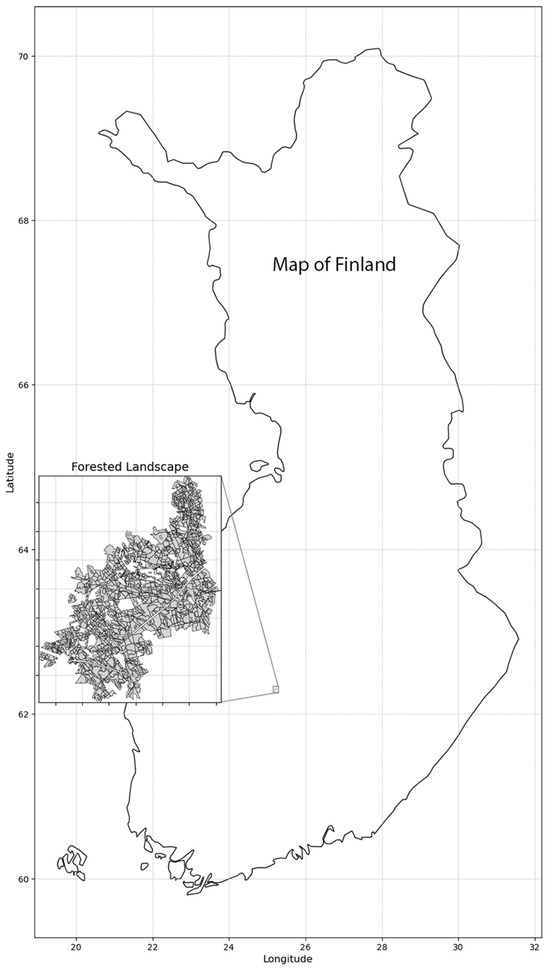

To estimate how different forest management strategies would affect the salutogenic forest characteristics via the included PSDs, we used SIMO, an open-access boreal forest growth simulator. It is an empirical and deterministic simulator, developed and parameterized for Finnish forest management [33]. SIMO simulates tree growth, mortality, and regeneration for even-aged [34] and uneven-aged boreal forests [35]. Since most of the landscapes in central and southern Finland are privately owned, we simulated a privately owned production forest landscape of 2250 ha, containing 1458 stands of different ages (Figure 2, Table 3) [36]. The area is a typical Finnish production forest landscape, with the data obtained from the publicly available forest statistics database www.metsään.fi. The main trees are Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris, in 50% of the stands), Norway spruce (Picea abies, 32.6%), silver birch (Betula pendula, 10.4%), and other deciduous trees (9%).

Figure 2.

The simulated forested landscape, 2250 hectares across 1458 stands, privately owned and located in southern/central Finland.

Table 3.

Summary of the attributes of the 1458 stands included in the simulations.

The input dataset contains information on the location and tree layers of each stand. The output datasets contain forest stand characteristics resulting from individual forest management actions (e.g., thinning, harvesting, planting) implemented following a variety of management regimes. We selected a set of the five most distinct management regimes to allow comparison between regimes and effects on salutogenic properties. In addition to rotation forest management (RFM), we simulated four alternative management regimes: RFM without thinning, replacing RFM with two variations of continuous cover forestry (CCF), and leaving the forest developing without any active management (Protection).

We simulated the development of each stand under these regimes over 100 years (2016–2116) in twenty 5-year time steps. The outputs of simulations for each time step and management regime were translated into forest structures linked to the described salutogenic properties (Table 2). The simulation length of 100 years allows for a representation of the full rotation length of the standard, business-as-usual RFM that is dominant in Finland [37]. The RFM scenario follows the national forest legislation and can, therefore, represent the benchmark with which to evaluate the impact of alternative forest management regimes. The average current rotation length under RFM is 70–90 years and varies across Finland, with relatively shorter rotation lengths in southern Finland and longer rotation lengths in northern Finland. Rotation length also differs with site-specific characteristics such as dominant tree species and soil fertility and type. Table 4 provides a detailed description of the analysed management regimes with respective expected outcomes on forest structure and indications for expected salutogenic properties.

Table 4.

Description of the five management regimes applied for a 100-year simulation period in forest stands within a production forest landscape in Finland (n = 1458) with hypothesised effects on perceived sensory dimensions (PSDs) and salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs) moving into the future. Serenity, in our study only, and depending on the distance to roads, is constant across managements and hence not shown. Symbols represent positive (+), negative (−), or neutral (0) hypothesised effects on salutogenic properties compared to rotation forest management. BA = basal area.

3. Results

Overall, our results indicate a clear difference between the Protection (set-aside/no management), rotation forestry (RFM), and continuous cover forestry (CCF) regimes, both regarding support for singular perceived sensory dimensions (PSDs) and in relation to our aggregated salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs), much in line with our expectations.

3.1. Perceived Sensory Dimensions (Individual PSDs)

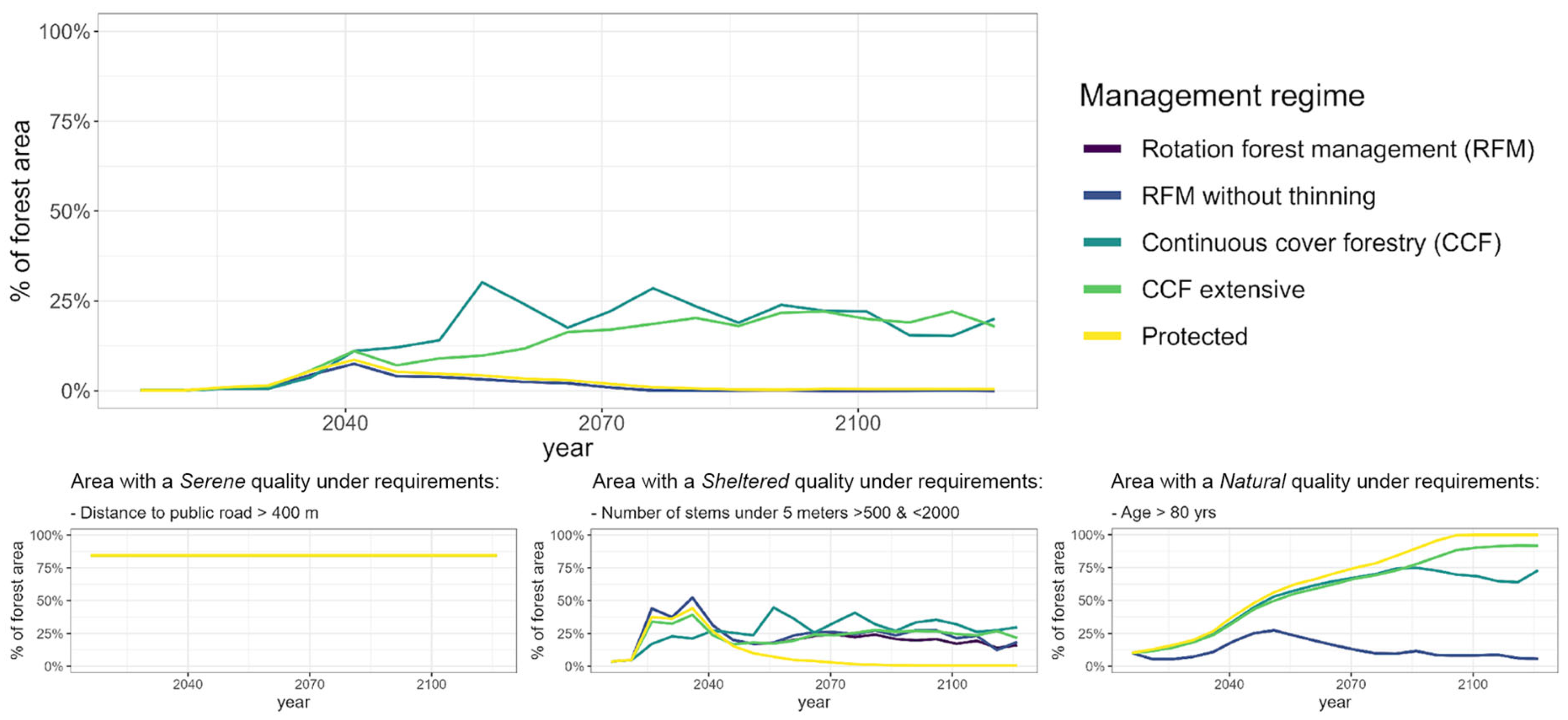

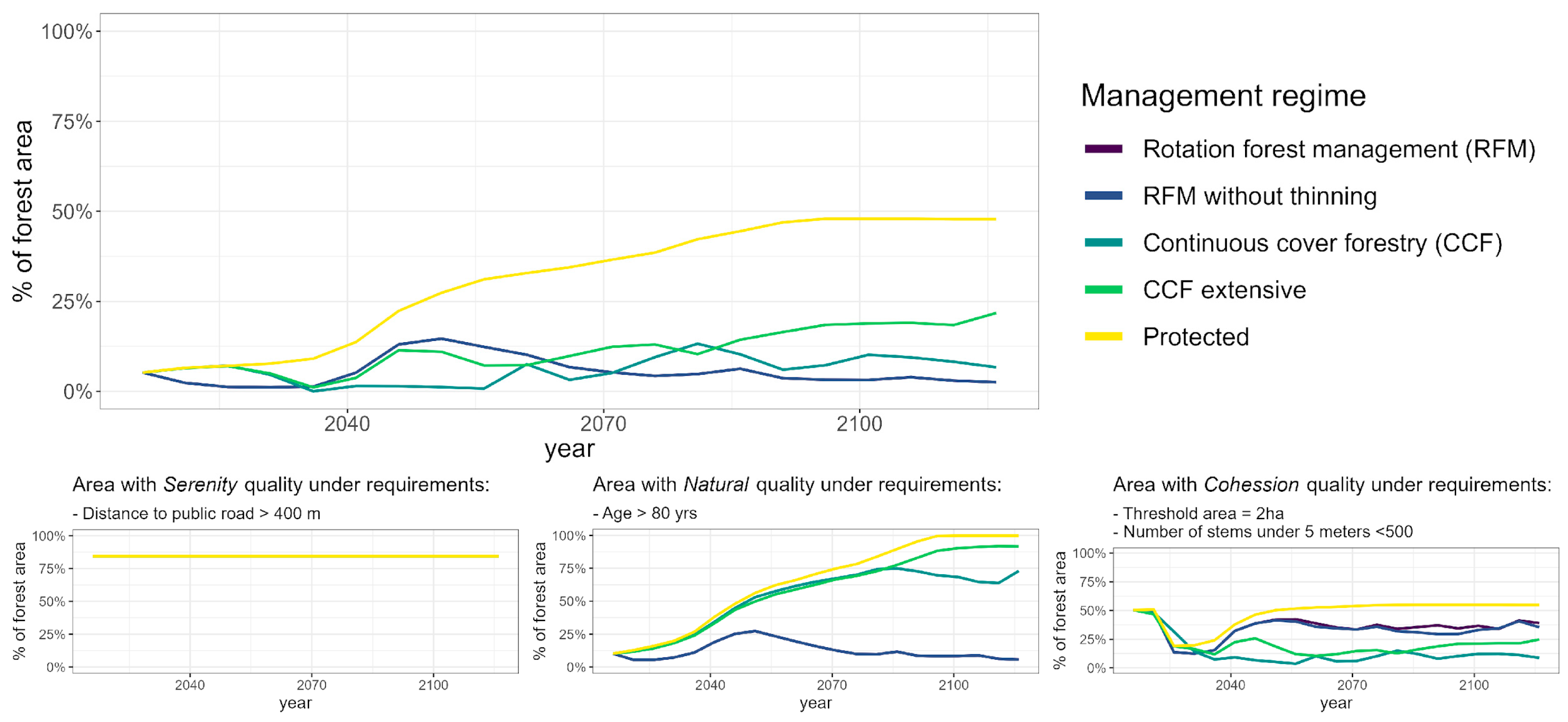

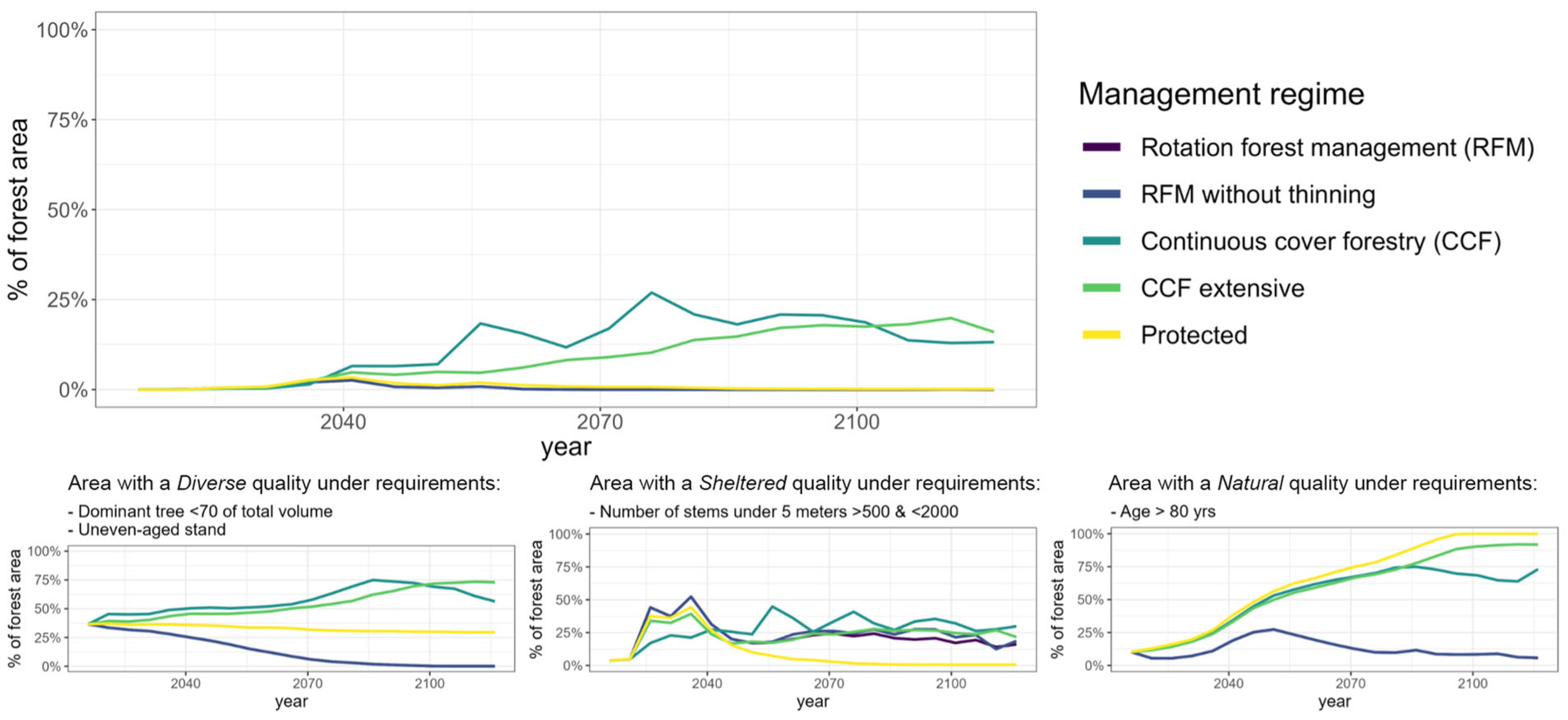

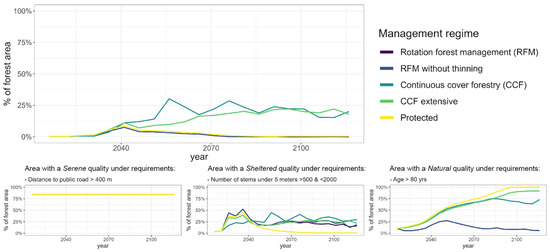

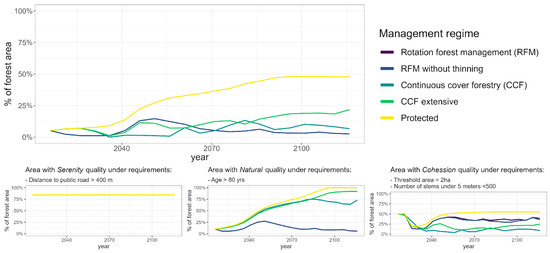

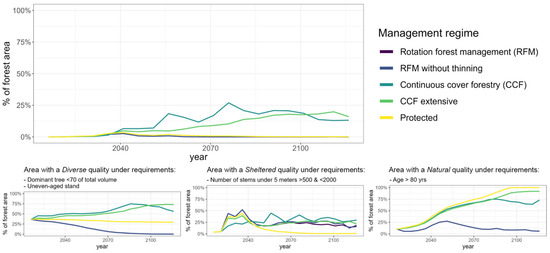

The Serene PSD was defined by the static measure distance to the road and, thus, was not dependent on any management regime. In our landscape, 85% of the forests fulfilled the conditions for serenity, reflecting that most roads are gravel, slow-speed, and scarcely frequented roads (Figure 3). The Natural PSD, indicated by volume-weighted average tree age above 80 years, was modest at its initial (current) state, with only 10% of the forest fulfilling this condition. This PSD was provided best through the protection and extensive CCF management regimes (Figure 3). The Sheltered PSD, representing the amount of relatively small trees sheltering horizontal visibility, had a very limited area at the initial state (3.7%) but increased steadily over time. It was provided by all management regimes, although, for Protection, this PSD declined over time because of older trees with a dense canopy, impeding small trees from thriving (Figure 3). The Cohesive PSD was well represented at its initial state (50%) and was best achieved through Protection, followed by rotation forest management practices and, lastly, by CCF (Figure 4). Finally, the Diverse PSD, associated with tree species and age diversity, covers about a third of the landscape at the initial stage (36%). It was best provided through CCF regimes, followed by Protection, while RFM regimes, promoting homogeneous forests, provided the least of this PSD (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Proportion of the landscape that fulfils the Deep salutogenic forest characteristic (SFC) when the whole landscape is managed according to a specific management regime. Small figures represent the proportion of the landscape that fulfils the perceived sensory dimensions (PSDs) required for a Deep SFC to emerge.

Figure 4.

Proportion of the landscape that fulfils the Spacious salutogenic forest characteristic (SFC) over time, when the whole landscape is managed according to a specific management regime. Small figures represent the proportion of the landscape that fulfils the perceived sensory dimensions (PSDs) required for a Spacious SFC to emerge.

Figure 5.

Proportion of the landscape that fulfils the Mixed salutogenic forest characteristic (SFC) over time, when the whole landscape is managed according to a specific management regime. Small figures represent the proportion of the landscape that fulfils the perceived sensory dimensions (PSDs) required for a Mixed SFC to emerge.

3.2. Salutogenic Forest Characteristics (SFCs)

Overall, it is worth noting that in our typical intensively managed and privately owned forest landscape, there was only a small fraction of the landscape fulfilling requirements for any of the three salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs), i.e., synergistic PSD combinations, here defined as Deep, Spacious, and Mixed forest characteristics, respectively. All three SFCs were present at less than 5% at the initial state (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). One key constraint affecting this was the shortage of the Natural PSD, common for all three SFCs, with only 10% of the forest being more than 80 years old. The Deep SFC (Natural–Sheltered–Serene) was best provided through CCF management, as PSDs Natural and Sheltered were consistently provided under this regime, while the Serene quality was the same regardless of management (Figure 3). Deep forest characteristics could be provided by 25% of the landscape in the long term, especially by the less extensive version of CCF (Figure 3). The Spacious SFC (Natural-Cohesive-Serene) was best provided under Protection (Figure 4). The extensive CCF performed slightly better than the standard CCF for this forest characteristic. Under a Protection regime, the Spacious SFC could cover close to 50% of the forest area in our landscape in the long term, whereas an extensive CCF regime would only support around 20% of the landscape area with these characteristics (Figure 4). Finally, the Mixed SFC (Natural–Sheltered–Diverse) was best provided by CCF, as all the PSDs required for this forest characteristic were consistently well provided under this regime. In the long term, using only CCF, approximately 20% of the forest landscape could provide a Mixed SFC (Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The overall aim of our study was to investigate how salutogenic properties of forest stands could change in the long term under different forest management regimes. This investigation was based on first interpreting and translating the PSD model (Figure 1) into a forest context (research question 1) and representing it in a forest simulation tool with suitable structural parameters (research question 2). This was then used to investigate how individual PSDs and some meaningful combinations of PSDs, defined using three salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs), could develop in the coming 100 years under different forest management regimes (research question 3). All in all, our scenarios indicate that uneven-aged management practices, such as CCF and Protection (set-aside/no management), might have an important role in providing salutogenic forest properties moving into the future. These regimes consistently produced more promising results in our simulations when considering meaningful combinations of salutogenic properties.

4.1. Management Regimes and Salutogenic Properties

4.1.1. Rotation Forest Management (RFM)

Rotation forest management (RFM), our baseline management regime, commonly produces a uniform and homogeneous forest structure, which could suggest some support for the Cohesion PSD if the stand size criterion is fulfilled. However, this perceived quality is also associated with good horizontal visibility and possibilities for mobility and exploration [20]. Such aspects might be contradicted by the relatively low tree age under an RFM regime since this also implies higher density stands. In addition, this would also suggest weak support for the Natural PSD, which is highly dependent on older trees to be strongly perceived [26]. This, in turn, would indicate weak overall support for all three SFCs in our study, in line with our findings. RFM without thinning would typically produce an even denser vegetation structure, again suggesting opportunities for a Sheltered quality to emerge at the expense of the Cohesion PSD. An increased presence of deadwood under this regime might slightly increase the potential for experiences of a Natural quality, as well as Diversity, which, together, would suggest increased support for the Mixed SFC to emerge, as well as the Deep SFC when combined with Serenity. However, again, weak overall support for the Natural PSD due to low age, as well as the dense structure, which is detrimental to the Cohesive PSD, would indicate low support for all three SFCs. All this is in line with our findings, with both RFM strategies producing very similar results across PSDs, with baseline RFM, as expected, slightly favouring the Cohesive PSD and RFM without thinning, slightly emphasising the Sheltered quality. This suggests that our chosen indicators for these PSDs worked as intended. In relation to our three SFCs, i.e., the Spacious, Deep, and Mixed forest characteristics, the differences between these two management strategies were again small, with weak overall support for all three SFCs.

4.1.2. Continuous Cover Forestry (CCF)

In general terms, a continuous cover forestry (CCF) regime would support natural regeneration, the promotion of natural growth patterns, tree species mixture, age variations, and, over time, the presence of older and larger trees, all suggesting strong overall support for the Natural PSD. A variation of tree species and the trees of different ages under this regime also indicates support for a sense of Diversity in the stand. At earlier stages, when vegetation is denser, a Sheltered quality would probably be more pronounced while, as stands become older and less dense, the sense of Cohesion might gradually increase. Overall, this suggests potentially strong support for all three of our salutogenic forest characteristics over time, confirmed by our simulations here. Our less extensive variant of CCF provided more of the Deep SFC (Natural–Sheltered–Serene) than any other regime in our study, as the Natural and Sheltered PSDs were consistently provided under this regime (Serenity being the same regardless of management, see Figure 3); 25% of the landscape could support the Deep SFC in the long term under this regime. The Mixed SFC (Natural–Sheltered–Diverse) was also best provided by this version of CCF in our simulations, as all PSDs required for this characteristic were well provided over a 100-year timespan (Figure 5). In the long term, using only this regime, approximately 20% of the forest landscape could provide a Mixed SFC. An exception was that the more extensive CCF management provided more of the Spacious SFC, possibly due to stronger support for a Natural quality long term, as well as producing a slightly less dense structure over time, both supporting this SFC.

4.1.3. Protection (Set-Aside/No Management)

In a general sense, Protection (set-aside/no management) initially produces a dense forest structure that might increase opportunities for a Sheltered quality, while an increased presence of deadwood might generally support experiences of the Natural and Diverse PSDs. This would indicate good overall support for our salutogenic forest properties, particularly the Deep and Mixed SFCs. Later stages with fewer but larger trees suggest support for the Spacious SFC over time due to increased support for the Cohesive PSD. Indeed, Protection management emerged as an important provider of the Spacious SFC (Natural–Cohesive–Serene) in our simulations, which was best provided under this regime (Figure 4). Under a Protection regime, the Spacious SFC could be provided by close to 50% of stands in our landscape in the long term, whereas the second-best regime in our simulations, the extensive version of CCF, would only support around 20% of stands with these characteristics in the landscape after 100 years. The small contribution of Protection to the Mixed and Deep SFCs in our study might be related to the initial (young) stage of the forest in this typical commercial forest landscape and the relatively short time projection (100 years) in relation to the slow growth of boreal forests. Within 100 years, Protection management was the best strategy for providing the Natural PSD. However, the trees did not have the chance to grow old enough in our scenarios to create typical small-scale dynamics that increase heterogeneity in tree species richness and age. From a longer-term perspective (beyond 100 years), Protection could better provide the Diverse and Shelter PSDs and, therefore, contribute to Mixed and Deep SFCs as well. Moreover, in our simulations, we did not account for the increasing rate of forest disturbance exacerbated by climate change, which is likely to affect heterogeneity in unmanaged forests.

4.2. Findings and Salutogenic Indicators in Relation to Other Studies

In a Polish choice experiment assessing public preferences for forest structure, respondents were reported to prefer older stands with vertical layering, irregularly spaced trees and a greater number of tree species [12]; characteristics corresponding well to the Natural and Diverse PSD qualities employed in our study here, thus providing support for the relevance of these PSDs in a forest context. Similarly, a preliminary report investigating public preferences for forest visits in ten European countries suggested that forests with a more complex structure and forests with taller and older trees are generally more preferred and generate higher recreational values, also supporting the relevance of these PSDs [38]. In another choice experiment study, people were presented with drawings of three forest stands differing in respect to tree species, height (as an age indicator), and distance to the site, representing their willingness to travel to the site [13]. It was found that stands with a mix of tree species—in our study, stands supporting the Diverse PSD and Mixed SFC (Table 1 and Table 2)—were, in general, preferred compared to monocultures. Stands with trees of varying height (i.e., uneven-aged stands) were also preferred over stands consisting of trees of the same height (i.e., even-aged stands). Based on such findings, it has been suggested that forests that are extensively managed or left unmanaged (Protection in our present study) for biodiversity purposes are likely to be more attractive to humans for recreation, a suggestion much in line with our findings [12]. Greater management intensity is otherwise suggested to indicate lower recreational values (ibid.), in line with our findings, where variants of RFM indicated lower support for salutogenic properties moving into the future.

Although Agimass et al. [9] suggested a positive influence on recreational value with a higher proportion of broadleaves, Sun et al. [39] reported Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) to potentially be more efficient in promoting psychological restoration than Japanese white birch (Betula platyphylla). In this analysis, we did not explicitly consider the proportion of broadleaves, however, stands fulfilling the conditions for the Diverse PSD are likely to show some variation in the conifer/broadleaves ratio. On the other hand, Stoltz et al. [26] did not identify any differences in the contribution between broadleaves and conifers on perceived restorativeness in boreal forests but concluded tree age to be the more determining factor.

Another factor mentioned in studies on forest structure in relation to health promotion is stand density. In our salutogenic model, this was present via the Sheltered (high density) and Cohesive (low density; Table 1) PSDs. In a review and meta-analysis of the literature comparing therapeutic effects of different forest densities, Kim et al. [11] analysed twelve studies (nine from Asia and three from Europe, including one study each from Spain, Poland, and Finland) and found psychological restoration to, generally, be greatest in low-density forests, defined as stands with a density of less than 500 stems per hectare. This was the density threshold used for PSD Cohesion in our study, requiring less than 500 stems per hectare of trees 1.3–5 m in height to emerge (Table 1). PSD Sheltered, on the other hand, was defined as requiring 500–2000 stems per hectare of trees 1.3–5 m in height, to provide sufficient horizontal cover (Table 1). Since many studies have indicated this PSD as an important perceived characteristic for psychological restoration (“to see without being seen”; [19,24]), and although our measure here focused specifically on smaller (younger) trees, it is possible that the density interval for a Sheltered quality to emerge was set higher than necessary in our study. Further empirical studies might be needed to better understand the relationship between stand density and PSD Shelter in a boreal context, also focusing on the lower density threshold, i.e., when is a boreal forest too sparse for this restorative quality to emerge?

Probst et al. [14] modelled the potential for psychological restoration in German forest stands depending on the forest management regime. They based their models on the perceptions of both experts and non-experts and found, just as we did in our present study, Protection (set-aside) management to best support such mechanisms, followed by adaptation forestry. They proposed adaptation forestry as the most promising alternative to simultaneously meet other functions such as wood production demands. The authors also reported CCF as having a high potential to support restorative mechanisms in the short term but not in the long term. Such different results might partly stem from different outcome variables and salutogenic models; while the German study specifically focused on psychological restoration, our approach here also considered instoration as a salutogenic pathway. This could again indicate the necessity of different types of forest management at the landscape level to meet the different needs of the public, as well as from a forestry perspective.

4.3. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study: Challenges for Future Research

In our study, the initial structural state of the forest was mostly obtained from remote sensing data. This can particularly affect the accuracy of the understory for the first years, and, hence, the Shelter and Cohesion PSDs through effects on the horizontal shelter and openness at the human eyesight level. However, this effect of the initial state decreases with time as forests grow and are managed in the simulations. When trying to identify suitable indicators for perceived qualities, we are limited both by the state of empirical knowledge about how to best represent each PSD quality, as well as by which parameters are available to us in the employed simulation tool. Potential challenges in this regard in relation to stand density and the Shelter PSD have already been discussed. In addition, we also used binary indicators (i.e., thresholds) to define each PSD. However, perceived qualities presumably change more gradually with environmental properties. Amid the lack of empirical information required to define these gradual perception patterns, thanks to the use of a diverse pool of forest stands in the landscape, we believe our work still provides an informed understanding of the relative differences between managements regarding salutogenic benefits at large.

Although it might be interesting to think about what would change if we were to use a tool with higher resolution and different dimensions available as potential variables, weak general links between structural variables and people’s experiences of environments might make more open, i.e., simpler, models preferable. When machine learning was employed to reveal connections between PSDs reported at people’s favourite places in the landscape and structural landscape variables in a study in Northern Sweden, the resulting models were weak, with stronger correlations found with attributes connected to personal characteristics, such as the degrees to which a person identified as more or less nature or urban-oriented [15]. This result was in line with other studies suggesting generally weak links between objective landscape measures and perceived qualities [40]. This does not mean that estimating perceived qualities through objective landscape data, as done in our study here, is completely without merit. In another Swedish study, 30%–40% of the restorative potential of forest stands was explained by a small number of variables, with tree age being the single most important, presumably mediated via its contribution to the Natural PSD [26]. However, such estimates probably need to be complemented with knowledge about local users to guide landscape planning actions more precisely [15]. Thus, although predictability of the herein employed indicators on the level of the individual likely is limited without also considering various individual characteristics—largely remaining to be further explored—we do believe that our results provide good general indications for how different forest management actions may affect important salutogenic properties in boreal forest stands from a broad public health perspective.

Studies have also suggested the presence of historical sites to possibly increase the recreational value of forests [9]. This aspect was absent from our analyses, since the Cultural PSD (see Section 2.1), typically associated with such landscape features, was not considered here. It might be interesting for future studies to also include this aspect, together with aspects associated with the other two PSDs not considered in our study, i.e., the Social (associated with people, movement, built facilities) and the Open (associated with prospects, vistas, open fields) PSDs. Since such an analysis might then include aspects not typically associated directly with forest structural properties, a landscape-level analysis might then be more appropriate. A recent Swedish study at the landscape level, employing a machine learning approach with a large set of landscape parameters, reported water features, recreational infrastructure, and deciduous forests to increase the probability of choosing an area for recreation, while urban environments, noise, forest clear-cuts, and young forests had the opposite effect [41]. These are findings well in line with the salutogenic model employed here; although, since the landscape perspective was missing in our approach, water features, recreational infrastructure, and urban features were not included in our analyses.

In our scenarios, which were focused on developments at the stand level, we managed the entire landscape exclusively under one specific management regime (100% management scenarios). Therefore, our results are suitable for pinpointing the relative importance of different management regimes but do not inform about conflicts between salutogenic qualities, i.e., whether specific forest patches can consistently provide different salutogenic properties. We did, however, consider the development of different stand types over time, supporting somewhat complementary recreational needs. It could then be interesting for future studies to further investigate spatial relationships between such stand types and investigate how a varied patchwork landscape could be developed in the long term to support complementary salutogenic properties. Possible applications could include the planning for walking routes supporting complementary recreational needs and the estimation of aesthetic diversity at the landscape level from a perceived qualities perspective. As suggested by our findings, combinations of management regimes such as CCF and Protection could then be used to achieve a diversity of forest characteristics along these walking routes. Variants of, e.g., RFM could possibly be used in less accessible parts of the landscape to maintain production functions.

Furthermore, Agimass et al. [9] concluded that forests’ recreational qualities depend both on structural characteristics and the relative distance to people, along with ownership. They suggested state-owned forests, compared to privately owned forests as those simulated in our present study, to be generally preferable as recreational sites, due to the unrestricted recreational access allowed to the public. They further suggested that forests need to be accessible within residential locations for more frequent trips, which could greatly affect salutogenic outcomes. Neither forest placement in relation to the surrounding landscape, nor social aspects such as ownership, were considered in our analysis here and might be important for future studies to consider in addition to forest structure alone. Like Nordström et al. [25], it would also be interesting to further investigate the possible trade-offs of maintaining salutogenic properties while also supporting other forest functions, such as, e.g., wood production and biodiversity conservation. For example, previous studies have already identified Protection and CCF to be generally positive for biodiversity conservation and other functions such as carbon sequestration [36].

From a broader perspective, modelling salutogenic properties within homogenous predefined forest stands, as commonly performed and so also in our present study, possibly implies certain limitations for how well such properties can be represented. If salutogenic properties could be represented in a more seamless simulation environment, at a higher resolution, this might allow for more fine-tuned indicators, since they would not be limited spatially by arbitrary, relative to the perceived qualities in question, stand borders. It could, for instance, be a model in which individual trees are modelled, rather than homogeneous collections of trees, and in which borders around different forest characteristics would not be fixed but allowed to shift in the landscape, thus becoming another variable in the simulations. This, in turn, could open new possibilities to plan for, e.g., walking routes/consecutive paths along which different forest characteristics are represented. Potentially, such a simulation environment could also allow consideration of micro-variations in the forest structure, e.g., small glades and local variations in density or tree age with potential relevance for PSDs such as Shelter, Diverse, and Natural. It could also be about how the trees are placed in relation to each other in the landscape, e.g., appear as Natural, a PSD quality associated with seemingly self-sown and naturally developed vegetation, which, in turn, would require trees to not be of the same age or planted in straight lines. These are all possibilities that might be interesting for future studies to explore.

5. Summary and Conclusions

We interpreted five perceived sensory dimensions (PSDs), previously linked with positive health and well-being outcomes, in terms of forest structure and used combinations of these qualities to define three salutogenic forest characteristics (SFCs) to simulate how such health-promoting properties might be supported in the landscape long-term (100 years) following five different management regimes. Our results indicate variants of CCF and Protection (set-aside) to be preferred strategies to support structural properties promoting these perceived qualities in boreal forests, potentially contributing to both instorative and restorative salutogenic pathways. Although our indicator parameters for the investigated perceived qualities have not been empirically verified—more research is needed to validate, and, if needed, to adjust and refine them—we do believe that our presented results provide a good estimate of how important salutogenic properties might change over time in relation to the analysed management regimes. As such, our findings might be interesting to consider, e.g., for planners and policymakers, when deciding on different management strategies for boreal forests in relation to human health and well-being outcomes.

Author Contributions

J.S., P.G. and T.S. planned the study. J.S., with input from P.G. and M.G., developed interpretations of salutogenic qualities in a forest context. All co-authors worked together on identifying suitable indicators in the simulation tool for the included salutogenic qualities. D.B., M.P., R.D., K.E., A.T.-C. and M.M. ran the simulations and produced the resulting graphs. Together with P.G., T.S. and B.M.P., they also all contributed valuable input during the writing of the final manuscript, which was done by J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded through the 2017–2018 Belmont Forum and BiodivERsA joint call for research proposals, under the BiodivScen ERA-Net COFUND programme, for “BioESSHealth: Scenarios for biodiversity and ecosystem services acknowledging health”, with the national funding organisations Formas (grants no. 2018-2435), the Research Council of Finland (grant no. 326309), and the German Science Foundation (grant no. 16LC1805B) respectively.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study is available upon request to daniel.d.burgas@jyu.fi (D.B.) or kyle.eyvindson@nmbu.no (K.E.)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marušáková, L.; Sallmannshofer, M. Human Health and Sustainable Forest Management; FOREST EUROPE Study—Liaison Unit Bratislava: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Egorov, A.I.; Mudu, P.; Braubach, M.; Martuzzi, M. (Eds.) Urban Green Spaces and Health. A Review of Evidence; World Health Organization, European Centre for Environment and Health: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stier-Jarmer, M.; Throner, V.; Kirschneck, M.; Immich, G.; Frisch, D.; Schuh, A. The psychological and physical effects of forests on human health: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, K.; Grahn, P. The scientific evidence for nature’s positive influence on human health and well-being. In Green and Healthy Nordic Cities: How to Plan, Design, and Manage Health-Promoting Urban Green Space; Borges, L.A., Rohrer, L., Nilsson, K., Eds.; Nordregio: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Yan, Q.; Pan, Y.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y. Medical empirical research on forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku): A systematic review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordh, H.; Grahn, P.; Währborg, P. Meaningful activities in the forest, a way back from exhaustion and long-term sick leave. Urban For. Urban Green 2009, 8, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag-Öström, E.; Stenlund, T.; Nordind, M.; Lundell, Y.; Ahlgren, C.; Fjellman-Wiklund, A.; Slunga Järvholm, L.; Dolling, A. “Nature’s effect on my mind”—Patients’ qualitative experiences of a forest-based rehabilitation programme. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agimass, F.; Lundhede, T.; Panduro, T.E.; Jacobsen, J.B. The choice of forest site for recreation: A revealed preference analysis using spatial data. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füger, F.; Huth, F.; Wagner, S.; Weber, N. Can visual aesthetic components and acceptance be traced back to forest structure? Forests 2021, 12, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.; Cho, J.; Cho, S.-I.; Chun, H.-R. Can Different Forest Structures Lead to Different Levels of Therapeutic Effects? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giergiczny, M.; Czajkowski, M.; Żylicz, T.; Angelstam, P. Choice experiment assessment of public preferences for forest structural attributes. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filyushkina, A.; Agimass, F.; Lundhede, T.; Strange, N.; Jacobsen, J.B. Preferences for variation in forest characteristics: Does diversity between stands matter? Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, B.M.; Toraño Caicoya, A.; Hilmers, T.; Ramisch, K.; Snäll, T.; Stoltz, J.; Grahn, P.; Suda, M. Predicting the perceived restorativeness and its indicators of present and future forest stands. People Nat. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, J.; Lehto, C.; Hedblom, M. Favourite places for outdoor recreation: Weak correlations between perceived qualities and structural landscape characteristics in Swedish PPGIS study. People Nat. 2024, 6, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.M.; Glascoff, M.A.; Felts, W.M. Salutogenesis 30 Years Later: Where do we go from here? Int. Electron. J. Health Educ. 2010, 13, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Markevych, I.; Schoierer, J.; Hartig, T.; Chudnovsky, A.; Hystad, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; de Vries, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Brauer, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, P.; Stoltz, J.; Bengtsson, A. The Alnarp Method: An Interdisciplinary-Based Design of Holistic Healing Gardens Derived from Research and Development in Alnarp Rehabilitation Garden. In Routledge Handbook of Urban Landscape Research; Bishop, K., Corkery, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz, J.; Grahn, P. Perceived Sensory Dimensions: An Evidence-based Approach to Greenspace Aesthetics. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 126989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, J.; Schaffer, C. Salutogenic affordances and sustainability: Multiple benefits with edible forest gardens in urban green spaces. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jong, K.; Albin, M.; Skärbäck, E.; Grahn, P.; Björk, J. Perceived green qualities were associated with neighborhood satisfaction, physical activity, and general health: Results from a cross-sectional study in suburban and rural Scania, southern Sweden. Health Place 2012, 18, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pálsdóttir, A.-M.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Persson, D.; Thorpert, P.; Grahn, P. The qualities of natural environments that support the rehabilitation process of individuals with stress-related mental disorder in nature-based rehabilitation. Urban For. Urban Green 2018, 29, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, E.-M.; Dolling, A.; Skärbäck, E.; Stoltz, J.; Grahn, P. Forests for wood production and stress recovery: Trade-offs in long-term forest management planning. Eur. J. For. Res. 2015, 134, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, J.; Lundell, Y.; Skärbäck, E.; van den Bosch, M.A.; Grahn, P.; Nordström, E.M.; Dolling, A. Planning for restorative forests: Describing stress-reducing qualities of forest stands using available forest stand data. Eur. J. For. Res. 2016, 135, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Refshauge, A.D.; Grahn, P. Forest design for mental health promotion—Using perceived sensory dimensions to elicit restorative responses. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 160, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, J.; Albin, M.; Grahn, P.; Jacobsson, H.; Ardö, J.; Wadbro, J. Recreational values of the natural environment in relation to neighbourhood satisfaction, physical activity, obesity and wellbeing. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoltz, J. Layered habitats: An evolutionary model for present-day recreational needs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 914294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. Collaboration Group on Quiet Areas. A Good Sound Environment—More Than Merely Absence from Noise: Sound Quality in Natural and Cultural Environments; Report nr: 5709; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Bromma, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. Vägtrafikbuller—Nordisk Beräkningsmodell, Report 4653. Available online: https://www.naturvardsverket.se/4ac363/globalassets/media/publikationer-pdf/4600/978-91-620-4653-5-del1.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Rasinmäki, J.; Mäkinen, A.; Kalliovirta, J. SIMO: An adaptable simulation framework for multiscale forest resource data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 66, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynynen, J.; Ohansuu, R.; Hökkä, H.; Siipilehto, J.; Salminen, H.; Haapala, P. Models for Predicting Stand Development in MELA System (2002) (Metsäntutkimuslaitos). 2002. Available online: https://jukuri.luke.fi/handle/10024/521469 (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Pukkala, T.; Lähde, E.; Laiho, O. Species interactions in the dynamics of even-and uneven-aged boreal forests. J. Sustain. For. 2013, 32, 371–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyvindson, K.; Duflot, K.; Triviño, M.; Blattert, C.; Potterf, M.; Mönkkönen, M. High boreal forest multifunctionality requires continuous cover forestry as a dominant management. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Äijälä, O.; Koistinen, A.; Sved, J.; Vanhatalo, K.; Väisänen, P. Hyvän Metsänhoidon Suositukset [Good Forest Management Recommendations]; Forestry Development Center Tapio: Helsinki, Finland, 2014. (In Finnish) [Google Scholar]

- Giergiczny, M.; Jacobsen, J.; Glenk, K.; Meyerhoff, J.; Abildtrup, J.; Agimass, F.; Czajkowski, M.; Faccioli, M.; Gajderowicz, T.; Getzner, M.; et al. Shaping the Future of Temperate Forests in Europe: Why Outdoor Recreation Matters. Research Square. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-841881/v1 (accessed on 27 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.; Yin, J.; He, J.; Zhong, Y.; Ning, W. Physiological and psychological recovery in two pure forests: Interaction between perception methods and perception durations. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1296714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, E.; Sugiyama, T.; Ierodiaconou, D.; Kremer, P. Perceived and objectively measured greenness of neighbourhoods: Are they measuring the same thing? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 95, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, C.; Hedblom, M.; Filyushkina, A.; Ranius, T. Seeing through their eyes: Revealing recreationists’ landscape preferences through viewshed analysis and machine learning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 248, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).