Abstract

Urban parks enhance residents’ quality of life and health by fostering a harmonious relationship between people and nature, so effective park design needs to prioritize ecological protection, sustainable landscapes, and practical spatial structures to achieve these benefits. This study takes the typical case of urban park renovation and reconstruction—Kowloon Walled City Park—as an example to conduct research and divides the interior of the park into four types of areas: contemporary built-up area; historical relic area; natural–folk custom area; and ecological conservation area. Based on 405 valid questionnaire data for respondents, this study conducts empirical research using a combination of the Semantic Differential (SD) method, Importance Performance Analysis (IPA) model, and unordered multivariate logit choice model, comprehensively describes and analyzes individual spatial perception and preferences, and further discusses the potential factors affecting individual perception preferences. The results show that there are differences in many characteristics between different areas in Kowloon Walled City Park. At the same time, people generally prefer park areas that integrate modern and traditional elements, natural and cultural environments, and pay attention to the balance between naturalness and sociality in park design. These results provide useful information for planners, developers, and others, as well as data for designing urban park construction with higher practical value and natural benefits.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Urban parks meet the important needs of park users through their internal landscape and environmental and spatial structure, so they are an important part of the construction and renovation of the city [1,2]. In today’s cities, all kinds of new and renovated urban parks are deeply integrated into people’s daily lives, reflecting the harmonious relationship between humans and nature. The significance of urban parks has been particularly pronounced in densely populated urban areas such as Hong Kong, where limited space and high population density necessitate the efficient and effective use of urban green spaces. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the role of urban parks as essential spaces for mental and physical well-being, altering users’ perceptions and increasing the demand for accessible green spaces. A study in New York City highlights the effects of COVID-19 on park use and sense of belonging, emphasizing the importance of urban green equity during the pandemic [3]. Additionally, studies have examined the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on recreational mobility, with findings indicating changes in park visitation behavior during the pandemic [4]. Furthermore, the relationship between historical redlining and park use during the COVID-19 pandemic has been investigated, highlighting how changes in park visits during the lockdown period are associated with redlining across census tracts in large U.S. cities [5]. Existing studies have mainly focused on the functions and services provided by urban parks, including improving the quality of the ecological environment, meeting recreational needs, and improving physical health [6,7,8]. In Hong Kong, urban parks like the Kowloon Walled City Park serve not only as ecological oases but also as cultural and historical landmarks, adding to their multifaceted importance in the urban fabric. Moreover, the pandemic has underscored the importance of these parks as safe and healthful retreats, thereby influencing user preferences for park landscapes and structures. Research shows that the pandemic has influenced visitors’ perceptions of urban woodlands, with leisure and recreation remaining the most important service in urban greenspaces [9,10]. Moreover, this study reveals a shift in motivations for visiting urban green spaces. While traditionally valued for physical exercise, relaxation, and nature observation, there was a notable decrease in non-essential visits. Instead, activities deemed necessary, like walking dogs, became more prevalent [11]. Since people express different preferences for the landscape and structure of urban parks, a data-driven approach to urban park design should be adopted to promote people’s physical and mental health [12,13]. This is particularly relevant in the context of urban areas, where diverse cultural backgrounds and lifestyles contribute to a wide range of user preferences. At the same time, individual preferences are also influenced by different spatial features and usage patterns of urban parks, and many researchers are studying and addressing such issues [14,15]. On the other hand, planning and decision-making processes related to urban parks are also changing as individual preferences change [16]. For instance, the metamorphosis of Kowloon Walled City Park from its historical origins as a fortification to its current iteration as a modern urban park exemplifies the potential of spatial perceived preferences to steer the redesign and rejuvenation of urban areas. This transformation exemplifies how attentiveness to community needs and preferences can ultimately harmonize park design with the desires of its users. Therefore, it is of both academic and practical significance to delve into the individual preferences for urban parks and the determinants that shape these preferences. Such insights are instrumental in informing more effective and inclusive strategies for urban park planning and design, with the ultimate objective of optimizing the synergistic relationship between urban residents and their natural environments.

1.2. A Literature Review

Previous studies have highlighted the difficulties associated with scientifically studying individual preferences because it has been observed that many attributes are interdependent and can impact each other’s functionality [17,18]. Additionally, personal preferences vary widely due to individual and household characteristics. Regarding personal preferences for urban parks, planners and architects are often faced with the complex task of balancing various elements and styles to cater to diverse user needs. Firstly, urban parks have natural attributes, which form the basis for their various functions. Contact with nature has been proven to positively influence human emotions, cognition, behavior, and physical health [19,20]. Therefore, the multifaceted role of urban parks in ecological improvement and social service necessitates a comprehensive approach to their design and management. When people interact with nature in urban parks, they usually engage in some type of recreational activity, which helps to promote their physical and mental health. Therefore, forms of human engineering in urban parks can also play an important role, and the application of ergonomic principles in urban park design can significantly enhance user experience [21,22,23,24]. In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought about significant changes in how users perceive and interact with urban parks. The impact of the pandemic on visitors’ health perceptions in therapeutic landscapes, such as urban wetland parks, has been investigated to understand the restorative experiences offered by these spaces during the pandemic. There is a growing recognition of the need for resilient and sustainable urban centers that can adapt to future crises [25]. In this context, urban park design must consider both immediate user needs and long-term resilience to ensure continuous provision of health and social benefits. In conclusion, urban park design should seek to strike a balance between natural and man-made environments to achieve optimal results that are better suited to a variety of individual preferences.

Existing research topics on urban park landscapes are relatively wide-ranging, covering a variety of perspectives such as structure, design, and layout [26]. However, a majority of the existing research in this field primarily focuses on comparing and discussing the impact of natural versus man-made environments. These studies often lack objective quantitative support and tend to be too descriptive, failing to provide actionable insights for practitioners. As a result, there is a need for a deeper understanding of why certain environments are more beneficial for human well-being [27]. To bridge this gap, this study draws on a comprehensive literature review and empirical data to investigate the nuanced relationship between urban park landscapes and user preferences. Therefore, this study aims to go beyond simply categorizing natural and man-made environments and instead seeks to explore the complex interactions between individuals’ personal characteristics and the quality and variability of the landscape in urban parks.

Previous studies have shown a limited exploration of how individual traits influence perceptions of various types of urban park landscapes and their preferences amidst landscape changes. Building on this foundation, our research seeks to provide a detailed analysis of the factors influencing park user preferences. Drawing on an extensive literature review and primary research data gathered through a questionnaire, this study aims to address specific research gaps. Firstly, it investigates the criteria used to categorize different areas within urban parks based on landscape characteristics. Secondly, it examines whether respondents favor natural, artificial, or both types of urban park environments. Finally, it explores the extent to which individual differences shape preferences for specific park areas. By focusing on the Kowloon Walled City Park in Hong Kong as a case study, this research aims to provide practical insights into urban park design that can be applied locally and globally. Using methods such as semantic differential analysis, importance–performance analysis (IPA), and multivariate logit choice models, this study seeks to emphasize the significant societal and ecological contributions of urban parks and aims to investigate practical urban park designs that can offer valuable insights for planners, developers, and government officials. Furthermore, the findings from this study can serve as a valuable reference for the construction of urban parks that prioritize practicality and yield ecological and economic benefits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

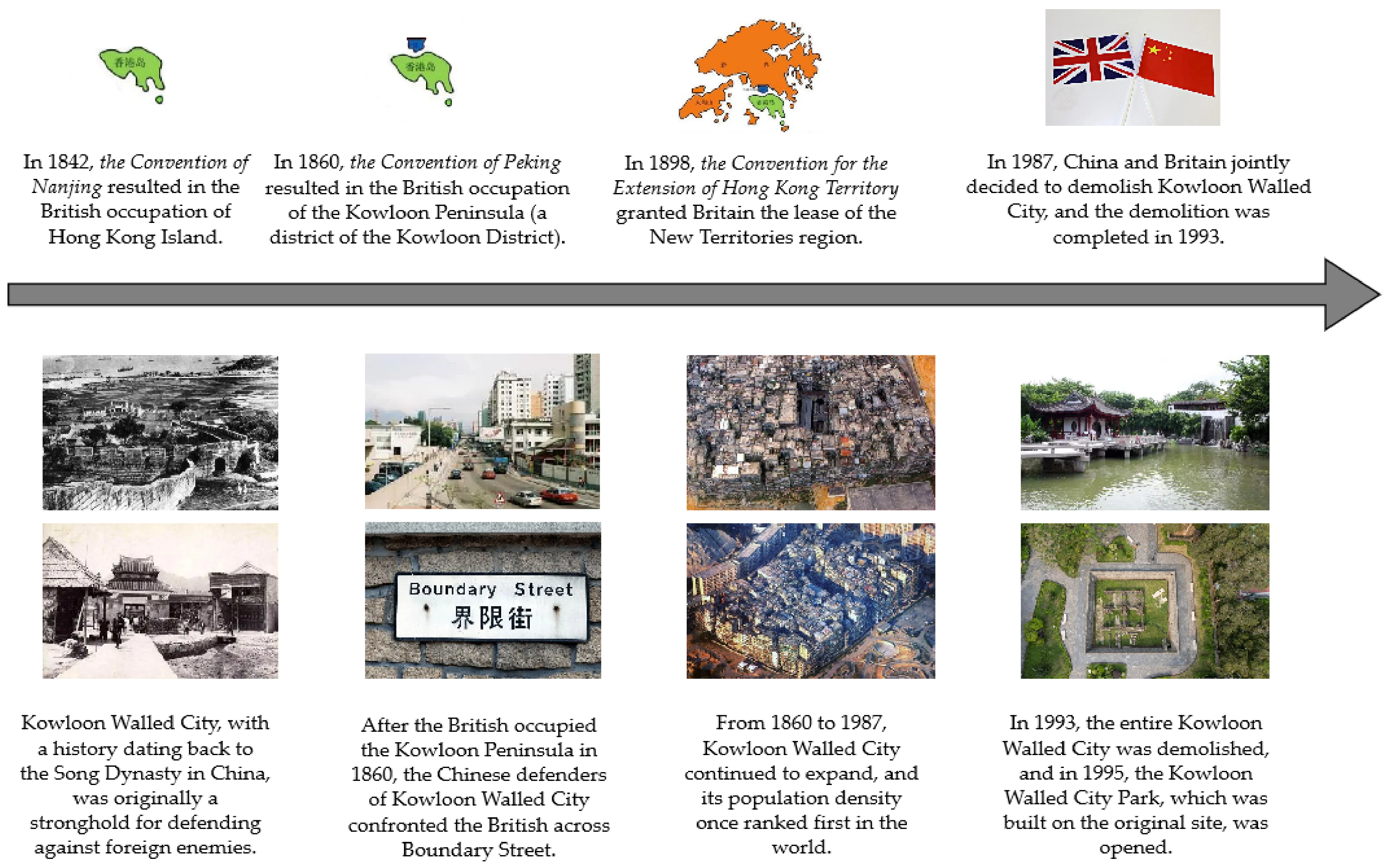

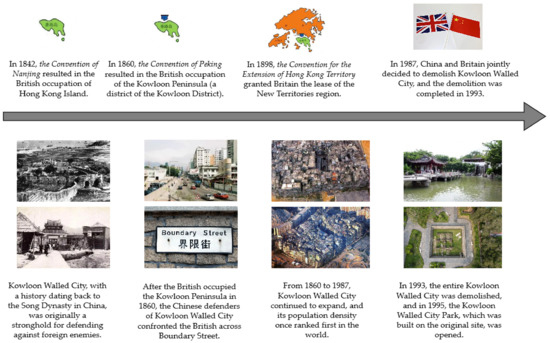

This study focuses on understanding public preferences for various types of urban parks. To achieve this, the study site selected is Hong Kong Kowloon Walled City Park, located in the city center of Hong Kong. Originally the site of Kowloon Walled City, this area served as a defensive position during the Ming and Qing Dynasties against maritime invasions and later became significant during the Sino–British confrontations following the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 and the Treaty of Beijing in 1860. Over time, Kowloon Walled City deteriorated into a densely populated urban enclave marked by poor living conditions and rampant illegal activities. The Kowloon Walled City was demolished in stages starting on 14 January 1987, under the Sino–British Joint Declaration, with the park opening in December 1995 on part of the original site (Figure 1). Covering an area of 31,000 m3, the park is divided into eight distinct scenic areas, serving social functions such as historical education and cultural preservation, as well as natural roles, including climate regulation and water resource management. Today, amidst the city’s growth and expansion, Kowloon Walled City Park and its surrounding areas have transformed into a vibrant hub for tourism and commerce in Hong Kong’s city center.

Figure 1.

Kowloon Walled City Park before and now (the above pictures come from the Internet (https://image.baidu.com (accessed on 22 July 2024)) and have been reassembled by the author).

Kowloon Walled City Park has been a popular destination for both locals and tourists since its opening. The park is renowned for attracting a significant number of visitors each year, with the average visit lasting between 1 and 3 h, depending on the activities engaged in and the facilities utilized. The park has carefully tended to the varied needs of different age groups by offering a spectrum of amenities designed to cater to the preferences of various users, such as the well-appointed small squares, shaded resting areas equipped with benches, and a network of well-maintained walking trails. While previous studies have not specifically quantified the impact of these facilities, anecdotal evidence indicates their popularity. Moreover, to enhance the enjoyment of the park’s scenery and to strengthen the connection between the park and its visitors, the park administration organizes daily free guided tours. These tours, led by experienced guides, take visitors through the park’s distinctive features and are accompanied by Cantonese commentary. Each tour lasts 45 min and can accommodate groups of 10 to 30 participants.

In summary, Kowloon Walled City Park is a typical area for this study due to its unique historical background and diverse spatial characteristics. The park’s design integrates modern, traditional, natural, and cultural elements, highlighting the challenges and opportunities associated with ecological protection and practical spatial design. Its redevelopment involves the preservation of historical relics while incorporating modern functionalities, offering valuable insights into the characteristics of different areas and user preferences. This makes Kowloon Walled City Park an ideal case for understanding how to balance these elements in urban park design, providing useful references for similar projects.

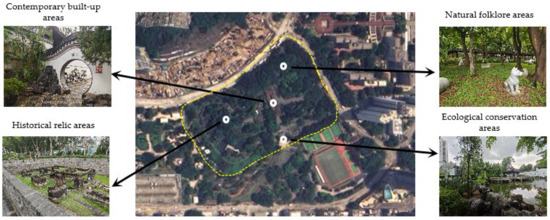

In terms of landscape, there are two common landscape types in the Kowloon Walled City Park and its surrounding blocks. One is the space transformed into a natural area due to the government’s increasing emphasis on adding more natural elements, thus changing its former image as a polluted and lawless slum. Compared with other areas, this area has a higher vegetation cover and more natural elements, and its main functions include rest and relatively passive appreciation. The other is the space transformed into a humanistic area, which maintains the historical elements of Kowloon Walled City Park to a certain extent, and its main functions also include the preservation of relics and folklore sightseeing. To examine the trade-offs between respondents’ perceptions of man-made and natural environments and explore their needs for these two types of areas, this study further categorizes them into four specific urban park zones, namely, contemporary built-up areas, historical relic areas, natural folklore areas, and ecological conservation areas [21,28,29].

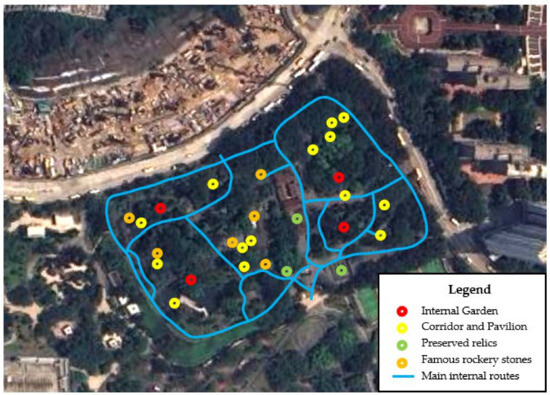

Furthermore, the climatic conditions of Hong Kong determine that the seasonal variations in Kowloon Walled City Park are relatively small, except for some special seasonal events. As a result, activities in this park do not change significantly due to seasonal variations, and its landscape is relatively unaffected by external factors, making it an ideal place to conduct field surveys as well as subjective and objective assessments of the impacts of landscape differences. Based on this, four representative areas of Kowloon Walled City Park were selected for this study as observation points for distributing questionnaires and conducting interviews, the distribution of which is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Categorization of the internal area of Kowloon Walled City Park (the above pictures were personally taken by the author and have been reassembled).

- (1)

- Contemporary built-up area. This form of the park is usually located on both sides of the main road inside the park, including some new exhibition halls and antique buildings. The function of this area is to fully satisfy the needs of park users for visiting and touring. Generally, people prioritize the experience of the natural landscape and ecological environment in urban parks. However, the city represents a complex socio-economic and ecological system, and the planning and construction of urban parks cannot be separated from the socio-economic development of the city. Thus, the modern built-up area is undoubtedly an important part of the Kowloon Walled City Park, which meets the social needs of individuals for rest and recreation within the park, and this is one of the outstanding features of the contemporary Kowloon Walled City Park, which embodies the composite function of modern urban parks. Specifically, various types of buildings within the contemporary built-up area can be used to demonstrate the history of the Kowloon Walled City Park through tools such as exhibition panels and display tools; at the same time, during the demolition of the Kowloon Walled City, some of the remains of the Walled City were unearthed and preserved as exhibits to be placed in the exhibition halls. This area is an important spatial carrier of the socio-economic functions of Kowloon Walled City Park and can be regarded as a reflection of the modern city and its integration with the history of the park;

- (2)

- Historical relic area. This area highlights the historical remains and original buildings in Kowloon Walled City Park, including the ancient relics specially preserved during the demolition of Kowloon Walled City, which emphasizes the preservation of historical and humanistic elements. Official records show that during the demolition and excavation of the Kowloon Walled City, two granite stone fronts engraved with the words South Gate and Kowloon Walled City were unearthed at the South Gate (the main gate of the Walled City). Similarly, the remaining wall foundations of the Walled City and its gates, the remaining drainage ditch of the inner wall of the Walled City, as well as the three cannons, stone beams, couplets, and column bases have all been preserved during the renovation. These precious historical relics reflect the history of the Kowloon Walled City Park and enrich the connotation and cultural heritage of the park. Therefore, the historical relics area is undoubtedly one of the vital parts of the Kowloon Walled City Park;

- (3)

- Natural folklore area. This area integrates modern and traditional elements, as well as natural and humanistic environments, especially the integration of natural landscapes into the design of the park. Kowloon Walled City Park contains eight scenic spots, which have their own characteristics and beauty and are integrated with the overall style and design of the park. As a result, the park possesses a large number of man-made elements, particularly highlighting the folklore and cultural heritage behind the park. In fact, an important trend in contemporary urban regeneration is to work based on famous scenic spots and historical sites and to focus on designs that capitalize on people’s nostalgia and attachment to folklore and culture. For example, the Garden of the Chinese Zodiac is themed around the twelve zodiac animals and uses traditional sculpture art to showcase Chinese traditional culture. In other words, the natural folklore area is not limited to the preservation of historical relics themselves but places greater emphasis on the integration and display of folk elements. The effects of these folk customs can be based on historical relics or re-established, which is the biggest difference between this area and the historical religious area. Therefore, the characteristics of the natural folklore area are consistent with the cultural elements contained in the Kowloon Walled City Park, and thus make it uniquely attractive. In conclusion, an ideal city park needs to realize the coupling of ecological and social benefits, and this area is the embodiment of this concept;

- (4)

- Ecological conservation area. This area represents the natural landscape area in the Kowloon Walled City Park. At the beginning of the park’s design, it was constructed based on the design of the classical gardens in the Yangtze River region in the early Qing Dynasty, with pavilions, elegant buildings, and beautiful natural landscapes everywhere in the park. Before the demolition of the Kowloon Walled City and the design of the park, the staff of the Hong Kong Regional Architectural Services Department had conducted in-depth studies and went to Mainland China to conduct site visits, and finally selected the most appropriate design for the park to place more emphasis on the pristine natural ecological environment rather than showing too many artificial decorations and alterations. As a result, today’s Kowloon Walled City Park is in stark contrast to the dirty and unkempt Kowloon Walled City of the past. With the continuous progress of urbanization and the rapid growth of the urban population, people’s demand for a natural ecological environment in the city is also increasing. Therefore, the natural ecological environment of Kowloon Walled City Park is receiving more and more attention.

In summary, this study aims to investigate the potential factors influencing respondents’ preferences for types of city parks. To achieve this, a survey and descriptive statistical analysis were conducted to assess respondents’ preferences. Subsequently, the four urban park areas mentioned earlier were treated as dependent variables in an econometric model. Multiple logit models were employed to measure and analyze respondents’ preferences for varying forms of urban parks.

2.2. Investigation Methods

This study designed the survey questionnaire (check Appendix A) in three steps. Firstly, a comprehensive literature review was conducted, which included analyzing previous studies on similar topics to identify key constructs and variables. Expert interviews were then conducted with five professionals in the field, including academics and practitioners, to gather insights and refine the questionnaire items, and the research group also held discussions to ensure that the questionnaire content addressed the core issues of this study. Secondly, this study identified and eliminated questions and answers with low reliability and validity through pre-survey activities to improve the overall quality of the questionnaire and made modifications, improvements, and final drafts to the questionnaire. To assess the validity and reliability of the data collection instruments, this study considered several factors, including content validity, which was evaluated by ensuring that the questionnaire items covered all relevant aspects of the constructs being measured through a comprehensive literature review, expert interviews, and research group discussions. It should be pointed out that the questionnaire design principles of this study are efficiency and comprehensiveness. The purpose is to ensure the quality of the questionnaire while making it as concise and clear as possible, thereby improving the response rate and effectiveness of the questionnaire. In terms of reliability, the internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient during the pre-survey. A Cronbach’s alpha value greater than 0.7 was considered acceptable, indicating good reliability of the instrument. In this regard, this article refers to previous research on improving questionnaire responsiveness [30].

On the basis of determining the survey questionnaire, our research team distributed 430 paper questionnaires and received 405 qualified questionnaires in Kowloon Walled City Park in July 2023, with an effective recovery rate of 94.19%. The number of respondents (405) was justified based on the need to achieve a statistically significant sample size that would allow for reliable and valid inferences to be made about the population. According to statistical guidelines and power analysis, a sample size of around 400 is generally considered sufficient to detect moderate effects with a high degree of confidence, assuming a normal distribution of data and a desired margin of error. Based on actual research experience, the average completion time for a comprehensive and high-quality citizen survey questionnaire is approximately 35–45 min. The selection of Kowloon Walled City Park as the survey site was strategic, as it is a high-traffic area with a diverse population, increasing the chances of obtaining a representative sample.

The research team designed a unified questionnaire and survey plan, with all investigators being graduate students with professional learning backgrounds and field investigation experience. Prior to the investigation, the researchers underwent a two-day training workshop that covered topics such as survey techniques, communication skills, and ethical considerations in data collection. The researchers received systematic training on research methods and data collection before carrying out their work, aiming to improve the efficiency and scientificity of the research activities. In terms of sampling design for questionnaire surveys, as questionnaire research belongs to quantitative research, that is, inferring overall characteristics through analysis of sample data, there are high requirements for sample representativeness and data quality [31]. Considering the complexity of the survey subjects, this study selected survey samples through a combination of stratified sampling and random sampling to improve sample representativeness and reduce sampling errors. Stratified sampling was used to ensure that each subgroup within the population was adequately represented, while random sampling was employed within each stratum to select specific participants. In addition, small gifts, such as umbrellas, handheld electric fans, etc., were given to the respondents to participate in the survey. In the specific investigation process, this study adopted a face-to-face approach and supplemented it with appropriate explanations from the research team’s investigators for any questions that might arise in the on-site paper questionnaire. Investigators were provided with a script to standardize explanations and to ensure consistency across all survey administrations. After the survey was completed, the research team ensured the quality of the survey data by cross-checking the questionnaire three times with the investigator. This quality control process involved a double-blind review where two members of the research team independently checked each questionnaire for completeness and consistency before data entry. This quality control process not only checked for completeness and consistency but also served as a measure of inter-rater reliability, ensuring that different investigators reached similar conclusions when reviewing the same data.

The details regarding the development of the instrument and the sources of the items are provided below. The instrument was developed through an iterative process that involved the initial draft based on the theoretical framework, followed by expert review and refinement. The final version of the instrument was then piloted with a small sample to further refine the items and assess the initial reliability. The sources of the items included the comprehensive literature review, expert interviews, and the research group discussions, as previously mentioned.

2.3. Statistical Research Methods

Relevant aspects of respondents’ perceptions have been an important part of urban spatial research [32,33,34]. Semantic Differential (SD), which is an objective and quantitative analysis of the research object, has been widely used in several research fields [35,36], which includes the study of overall urban space at the macro level and the study of specific buildings and street spaces at the micro level [37,38,39,40,41]. Based on several principles of the SD method, this study selected 12 pairs of adjective combinations used to describe the characteristics of Kowloon Walled City Park with opposite lexical meanings as evaluation factors and used them to construct a semantic difference scale for the evaluation of respondents’ perceptions of the park, as shown in Table 1. Specifically, the 12 pairs of adjective combinations identified in this study represent 12 evaluation items, which are embodied as the evaluation factors listed in the semantic difference scale. This study used a Likert five-point scale to set the evaluation scale level at 5, which is 5 interval values that were taken between each adjective combination and symmetrical with 3 as the midpoint, from left to right as 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Higher scores on each evaluation item indicated that the respondents’ perceptual evaluations were more biased in favor of the right evaluative factor adjectives, while lower scores indicated a greater bias in favor of the left ones.

Table 1.

Semantic Differential Scale for Perceived Evaluation of Kowloon Walled City Park.

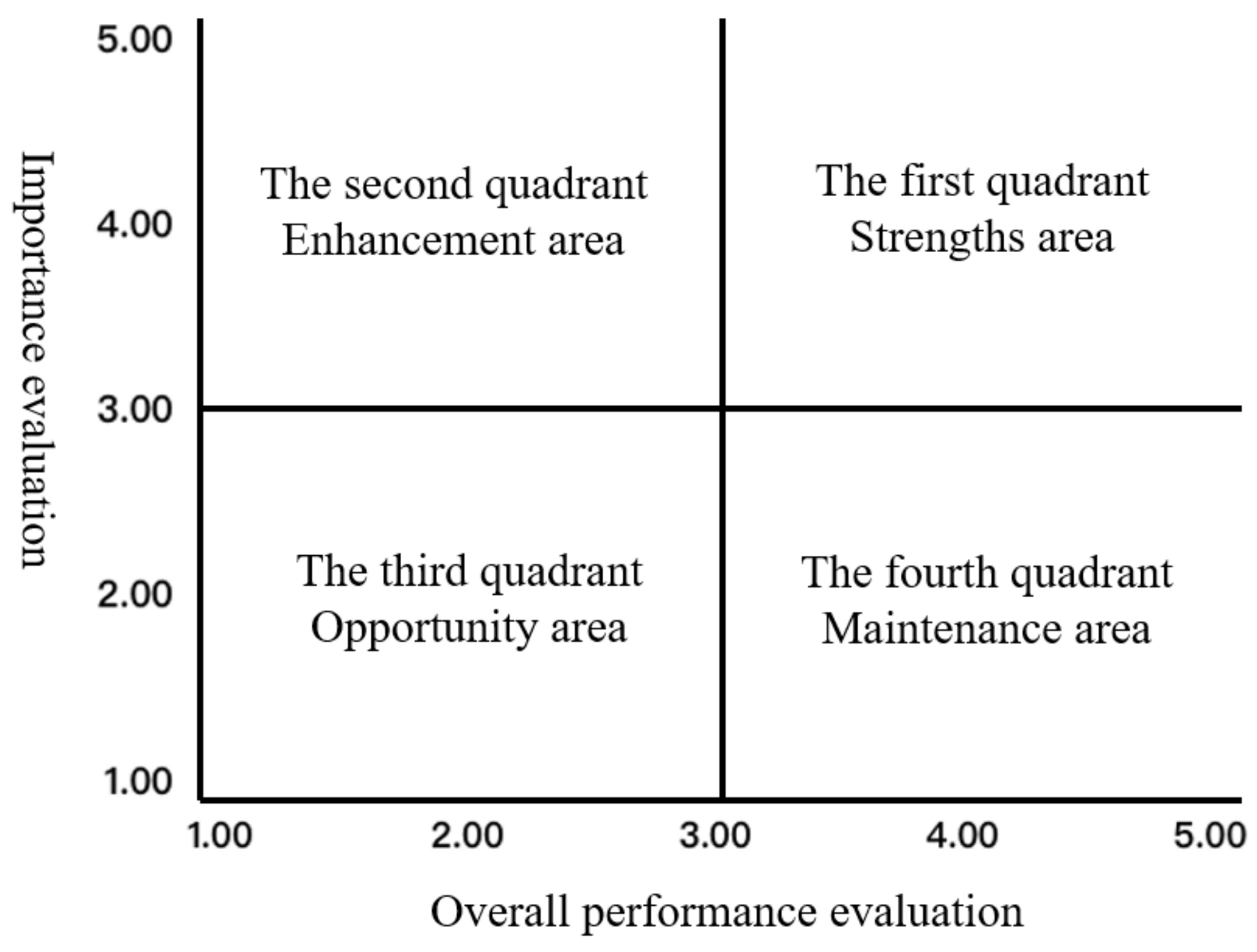

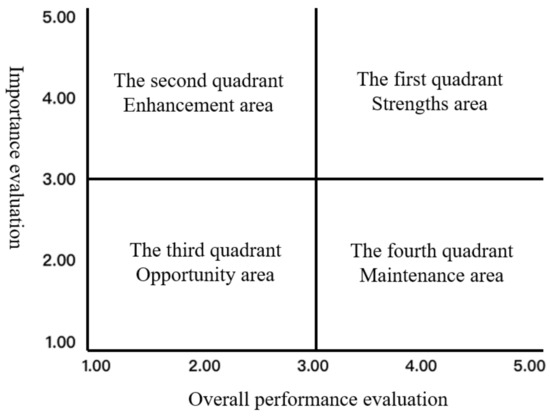

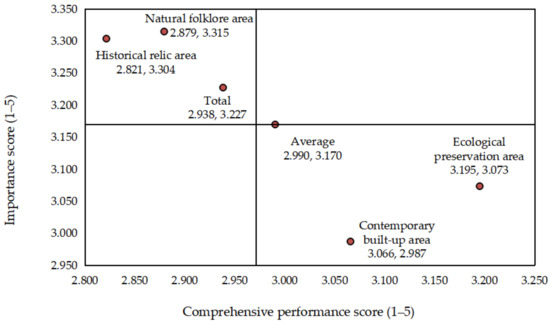

The importance–performance analysis (IPA) model is a widely used tool in various industries to prioritize service quality attributes and evaluate performance. In a recent study, it is also used in the land governance area [42,43]. In this study, the IPA model was employed to gauge and evaluate the overall perceptions of the different areas of Kowloon Walled City Park. The IPA model was divided into four quadrants, which were analyzed based on the importance scores (1–5 indicating very unimportant–very important) and overall performance scores (1–5 indicating worst performance–best performance). The results of respondents’ integrated perceptions can be categorized as follows: (1) The first quadrant is the Strengths area, where respondents believe that the factors in this area are very important and their performance is good; (2) The second quadrant is the Enhancement area, where respondents believe that the factors in this area are also very important, but their performance is not ideal and they need to focus on fixing and improving them; (3) The third quadrant is the Opportunity area, where respondents believe that the factors in this area are not vital and their performance is relatively poor. However, this does not mean that the factors in this zone can be ignored, but extra attention should be paid to the analysis of the causes and finding new breakthroughs to improve respondents’ satisfaction; (4) The fourth quadrant is the maintenance zone, where respondents perceive the importance of the factors in this zone to be low, but their performance is relatively good, so capturing these factors can have a positive effect. In terms of the measurement of the IPA model, this study used a five-point Likert scale to measure respondents’ perceptions of the performance and importance of the different zones in Kowloon Walled City Park, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) Framework.

Regarding the factors influencing individuals’ perceived preferences, in an earlier study conducted by Abello and Bernaldez (1986) [44], a significant correlation was discovered between specific aspects of personality and preferences. Additionally, respondents’ perceptions and preferences can be influenced by various individual functional and structural variables (such as gender, age, occupation) as well as social and cultural–political variables (such as income and social status). Hence, this study developed a questionnaire based on previous research to gather comprehensive and objective data, as presented in Table 2 [45,46]. In terms of reliability, the internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient during the pre-survey. A Cronbach’s alpha value greater than 0.7 was considered acceptable, indicating good reliability of the instrument. The results of the Cronbach’s alpha analysis are also shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors Influencing Respondents’ Perceptions and Preferences of Kowloon Walled City Parks.

2.4. Statistical Methods

This study constructed an unordered multivariate logit choice model for data analysis and compared respondents’ unordered choices of various urban park forms. We used a multivariate logit model for analysis, which involves more than two nominal response variables and consists of multiple formulas, where (j + 1) response variables generate j formulas, each of which compares a binary logit regression to a control group. In addition, the j binary logit regressions described above are estimated simultaneously in a multivariate logit regression.

In this study, the ecological conservation area was selected as the control group, and the contemporary built-up area, the historical site area, and the natural folklore area were selected as the experimental group. Based on the above framework, P(yi = j) is set as the probability of the experimental group, P(yi = 0) as the probability of the control group, and β as the logarithmic probability of the experimental group over the control group. The form of the model for this study is as follows:

In the above equation, the coefficients of the control group are nominally set to zero as the probabilities of the various options need to be harmonized. Then, the probability relative reference group can be obtained in the following form:

After transformation, the above formula can also be written as

In addition, in the unordered multivariate logit choice model, parameter estimation is performed using the appropriate computational methods. For respondent i, dij is set to 1 if option j is selected; if option j is not selected, then dij is set to 0. Meanwhile, for respondent i, only one of all (j + 1) alternative options can be selected; that is, only one dij = 1 can exist. On this basis, a joint probability function for yij (i = 1, 2, …, n; j = 0, 1, 2, …, j) is built, and the final logarithmic function is as follows:

It is important to note that before logit estimation, fitting tests and independent tests should be performed on the raw data. In this regard, the significance level of the variables can reflect whether they contribute significantly to the model and whether it makes sense to study them. The Cox and Snell coefficients and the Nagelkerke coefficients can show how well the model explains the changes in the original variables and whether the preference choices of the four urban park areas are consistent with the assumption that their utilities are independent of each other. The logit model can be used to estimate parameters only if the above conditions are met.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

As shown in Table 3, the proportion of males and females among the respondents was fairly even. More than 70% of the respondents were over 40 years old, showing a relatively high proportion of middle-aged and older people. Over 50% of the respondents had secondary education or above. The majority of respondents have three or more family members, with over 45% having a monthly household income of 25,000 HKD and above, which is in line with the average income in Hong Kong. Meanwhile, as an open and tolerant city, Hong Kong has seen a gradual increase in its foreign population in recent years, with close to 75% of respondents having lived in Hong Kong for only 10 years or less.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the sample (N = 405).

3.2. Semantic Differential Analysis

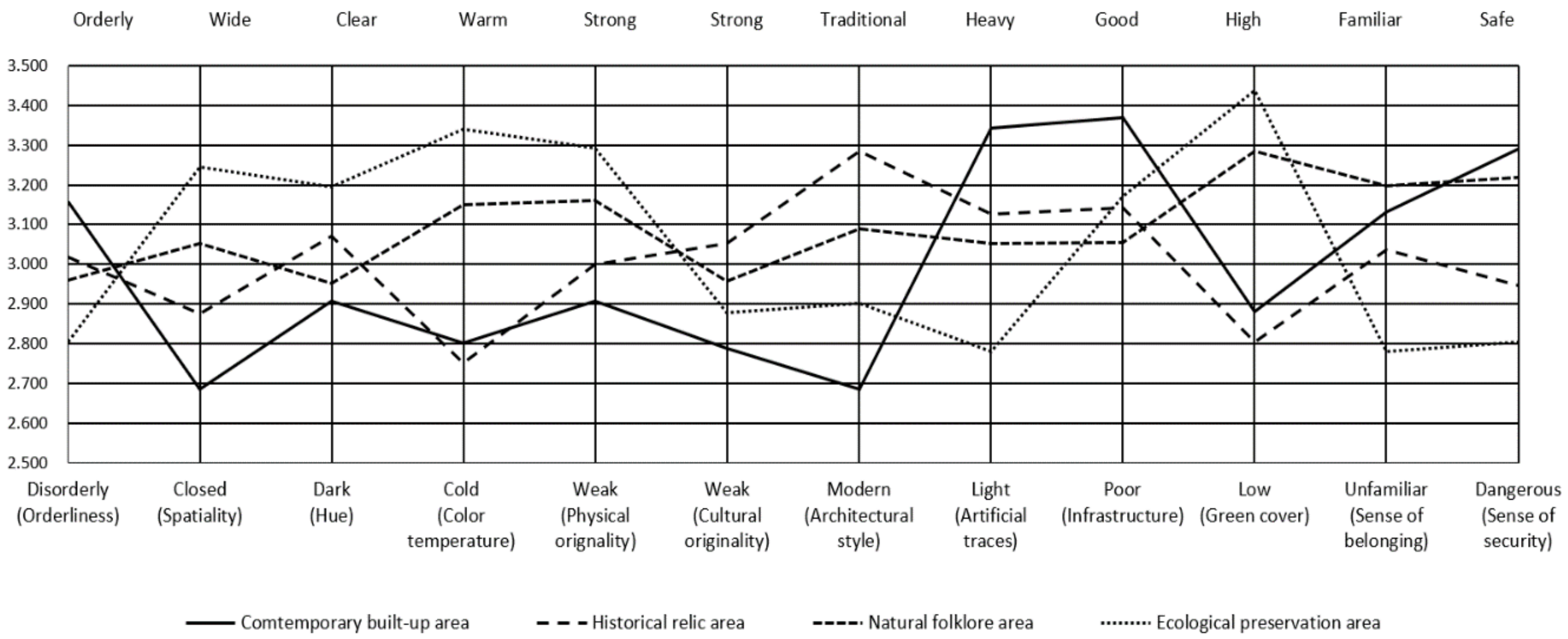

Based on the survey data, this study counts the data of each factor after assignment and obtains the SD factor score (Table 4). Results show that there are differences between different regions within Kowloon Walled City Park in terms of many characteristics, contemporary built-up areas, historical relic areas, natural folklore areas, and ecological conservation areas.

Table 4.

SD scores of different regions within Kowloon Walled City Park.

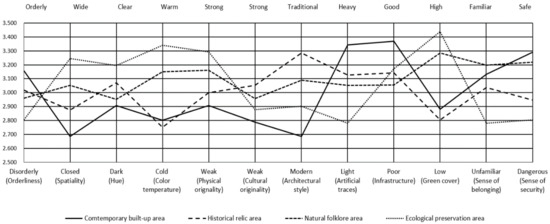

Based on the SD scores, the SD evaluation curves can be plotted (Figure 4). Overall, there are large differences in the perceptions of various types of areas in terms of spatiality, color temperature, architectural style, artificial traces, and green coverage, while the differences in the perceptions of hue, cultural authenticity, and infrastructure are relatively small. The conclusions are as follows: (1) The advantages of the contemporary built-up area are its orderly space, good infrastructure, and higher sense of security, while its disadvantages are its relatively confined space, dark hue, and weak physical and cultural authenticity, which are closely related to the specificities of the area; (2) The advantages of the historical relic area are stronger cultural authenticity, relatively traditional architectural style, and better integration with the natural landscape, while its disadvantages lie in its relatively cold color temperature and low green coverage; (3) The advantages of the ecological conservation area are quite obvious, such as the relatively high green coverage, strong physical originality, warm color temperature, bright hue, and open space, which are related to its preservation of the natural elements; (4) The main characteristics of the natural folk area are that it brings a relatively strong sense of belonging to the people, and at the same time, combines several advantages of the ecological conservation area, such as higher green coverage, stronger physical originality, and a relatively bright hue.

Figure 4.

SD evaluation curve of Kowloon Walled City Park.

3.3. Perceived Preference Analysis

Based on the data, this study analyzed respondents’ preferences for different areas within Kowloon Walled City Park. First, respondents were invited to select their favorite park areas to measure their preference ranking for each type of area; second, they were invited to rate each type of park area on a five-point scale, ranging from importance ratings (with scores of 1–5, indicating very unimportant–very important) and overall performance ratings (1–5 for worst performance–best performance). From the results shown in Table 5, the proportion of respondents who preferred the natural and folklore areas was higher than the proportion of respondents choosing the other three areas.

Table 5.

Respondents’ Perceptions and Preferences for Different Areas of the Park.

The results of the research show that respondents generally preferred areas that incorporated natural elements, but at the same time, they also expected a combination of modern and traditional elements and natural and humanistic environments. In particular, the respondents’ preferences reflect the trade-offs between naturalness and sociability in park design. As a result, it is essential to balance the naturalness and sociality of urban parks. The research area, the Kowloon Walled City Park, is a typical urban park in the city center of Hong Kong, and the area within and around it manifests a variety of features, including those related to the urban park itself as well as the history, social development, and the life of the residents. Respondents’ preferences for Kowloon Walled City Park, therefore, reflect their trade-offs between the natural and social aspects of parks.

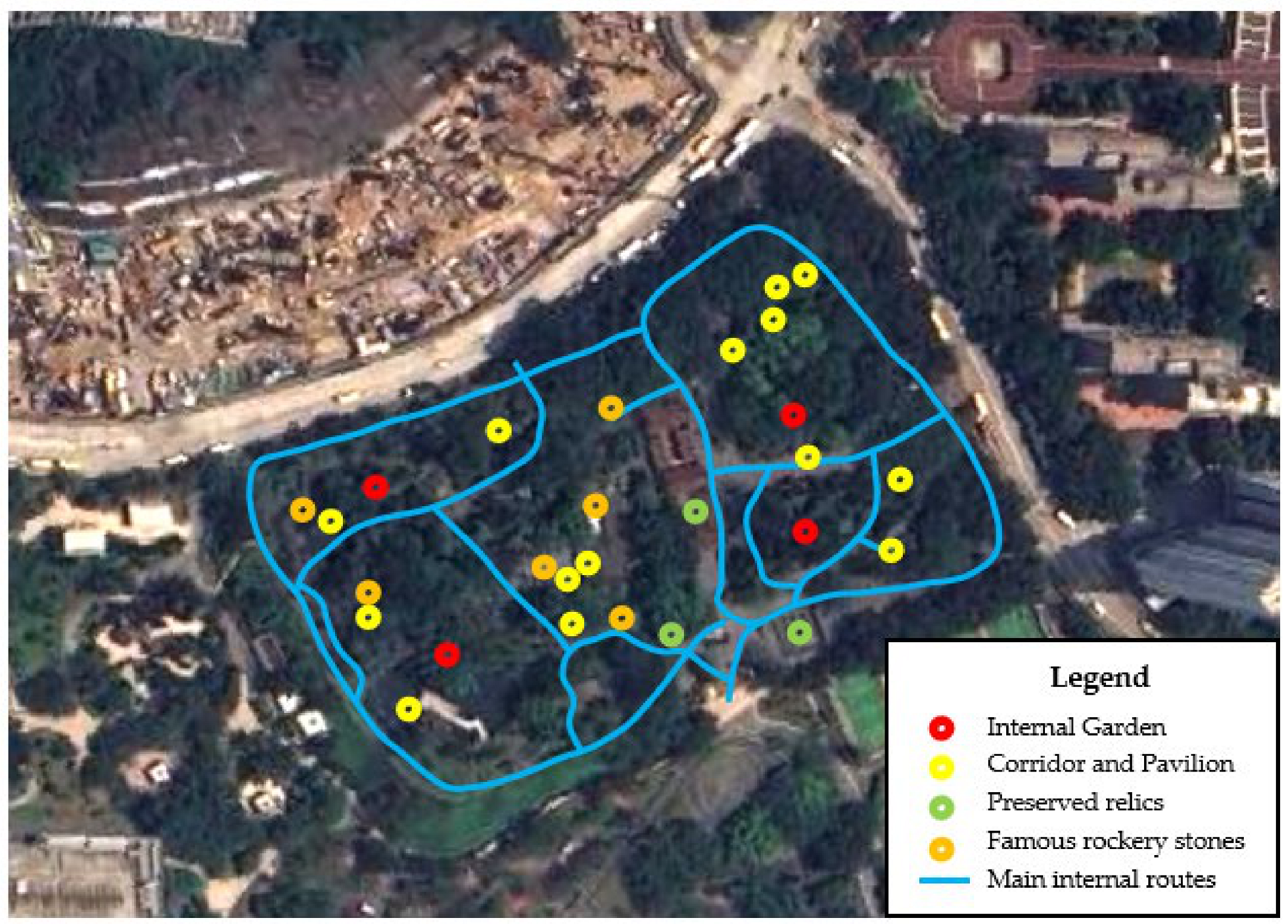

On the one hand, cities are complex socio-economic and ecological systems, and the design and renovation of the Kowloon Walled City Park, located in a busy area of Hong Kong, cannot be separated from the historical lineage as well as the socio-economic characteristics inherent in the city. In the analysis of respondents’ perceptions and preferences for different areas of the Kowloon Walled City Park, it was found that people generally preferred a park area with a blend of modern and traditional elements, natural and humanistic environments, which are the natural and folklore areas defined in this study. Accordingly, respondents tended to place equal priority on preserving the park’s historical and cultural heritage and creating its natural landscape. Figure 5 shows the main buildings, lakes, and green areas inside Kowloon Walled City Park. The yellow lines indicate the newly constructed antique buildings, promenades, and pavilions inside the park; the blue areas indicate the main lakes and water systems inside the park, and the green areas indicate the main green areas inside the park. Obviously, the design of Kowloon Walled City Park integrates modern and traditional architectural styles and considers the different natural and humanistic environments. This spatial layout not only maximizes the naturalness of the park landscape and atmosphere but also integrates various types of buildings that are in line with the overall style of the park, achieving the goal of maintaining the park’s authenticity. It should be noted that although the current urban renovation projects increasingly emphasize creating natural and ecological areas, as far as the city park is concerned, it should also reflect its composite function as far as possible; that is, the urban park is a park of the city, so the reasonable park design should also integrate some social elements into the park to extend the basic social function of the city park in the modern city. In the past, the excessive desire for flawless green lawns has caused groundwater pollution in the USA [21].

Figure 5.

Spatial Characteristics of Various Elements within the Kowloon Walled City Park: Main Buildings with Lakes and Green Areas.

On the other hand, in the process of renovating Kowloon Walled City Park, eliminating the original unfavorable factors of Kowloon Walled City as much as possible is also one of the main tasks. Therefore, the idea of renovating Kowloon Walled City has never been rigidly repairing the old but has rather been based on demolishing old buildings, preserving historical relics, and building new city parks; the goal is innovatively adopting a variety of methods to retain as much as possible the memory of the history of Kowloon Walled City. Figure 6 shows the spatial relationship between the main roads and the main attractions within the Kowloon Walled City Park. The red circles indicate the main attractions inside the park, including stone monuments, rockeries, and water pavilions, while the blue lines indicate the main roads inside the park. It can be seen that the attractions of Kowloon Walled City Park are generally designed to be situated on both sides of the park roads and the surrounding areas, with some of the roads being designed based on the location of historical sites and some of the roads being designed according to the overall design of the park. In addition, the various attractions tend to be the most popular areas of the park, as well as relatively crowded areas. Therefore, the design of roads in the park is a comprehensive project; in addition to connecting various types of attractions, it also considers how to meet the needs for rest, recreation, and other aspects. Whether users’ needs are adequately met can also be tested by their feedback on perceived preferences to see if the Kowloon Walled City Park has achieved a good balance between naturalness and socialism.

Figure 6.

Spatial Characteristics of Various Elements within the Kowloon Walled City Park: Main Roads and Major Attractions.

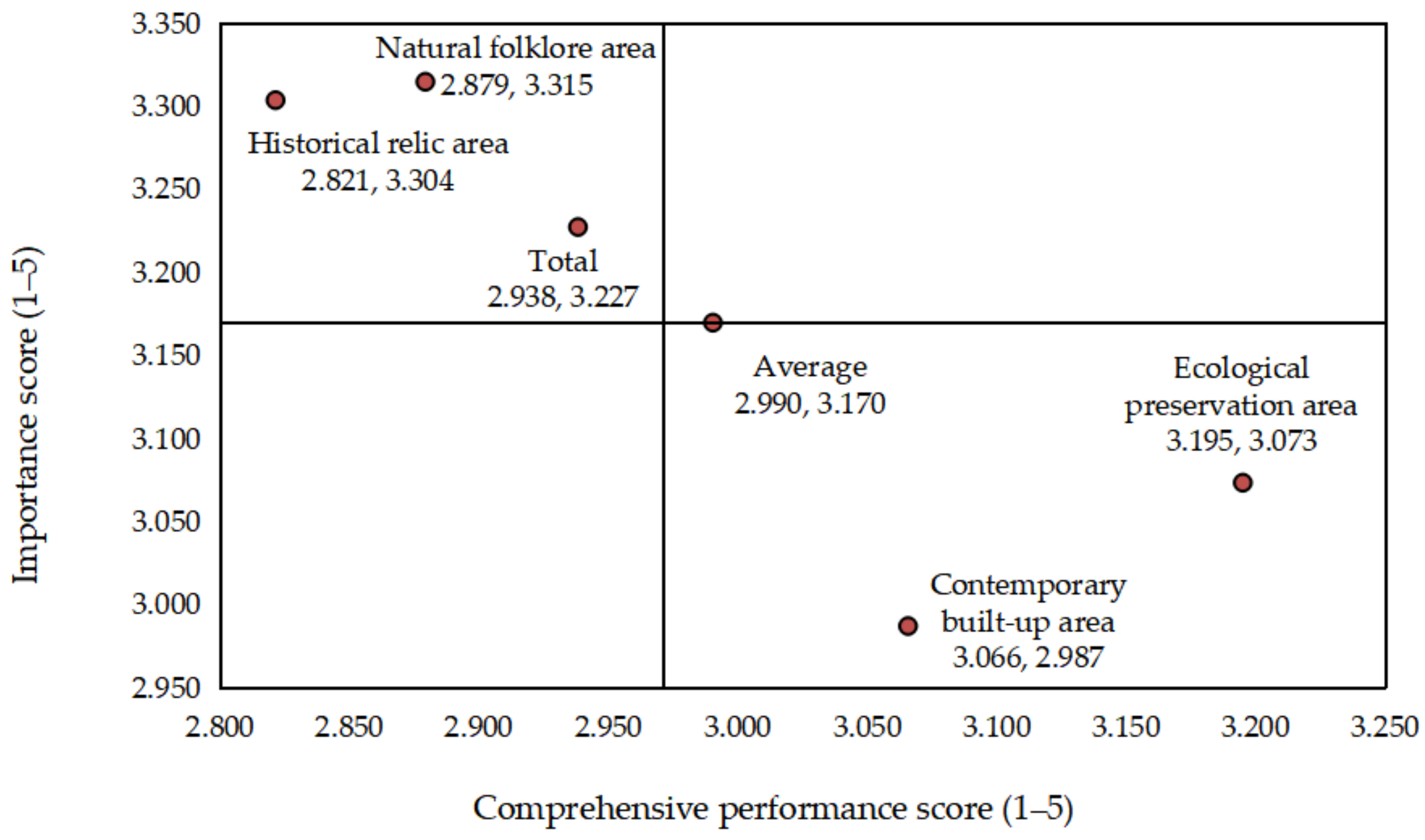

In addition, respondents’ perceived preferences for the four types of areas within the Kowloon Walled City Park are also based on their evaluation of the importance and performance of every type of element within the park. As shown in Figure 7, the average IPA points for the natural folklore area and the historical site area lie in the second quadrant in the upper left corner, which means that respondents consider the elements in this area very important, but their performance is not satisfactory, so emphasis should be put on restoration and improvement. For example, some immovable, irreproducible, and easily damaged historic sites should be protected in a more complete and scientific way; for the display of historical artifacts, innovative ways and means should be adopted to achieve better preservation and utilization. Moreover, the average IPA points for the contemporary built-up area and the ecological conservation area lie in the fourth quadrant in the lower right corner, and the interviewees think that the factors in this area are of low importance, but their performance is good. For example, compared to historic sites, buildings in the contemporary built-up area do not carry conservation value in the historical sense but take the roles of displaying cultural relics and providing public services. Similarly, compared to the chaotic state of the Kowloon Walled City prior to its demolition, the current ecological conservation area, with its large areas of mountains, water, lakes, and grasslands, takes on the role of maintaining the natural environment of the park and providing various types of ecological services. At present, these two areas are comprehensively performing well, and making full use of these factors in the next step can play a more positive role.

Figure 7.

Map of IPA analysis results of four types of areas within Kowloon Walled City Park.

3.4. Analysis of Influential Factors

To further explore the influencing factors of individual perceived preferences, multinomial logit regression analyses were conducted to link respondents’ perceived preferences for Kowloon Walled City Park with their individual characteristics. Firstly, the results of the fit test and independence test are shown in Table 6. It can be seen that most of the variables are significant at the 0.05 level, except for gender, which indicates that most of the variables contribute significantly to the model composition and will prove to be meaningful in the analysis. The likelihood ratio of the model was 636.373 (significant at the 0.01 level) with Cox and Snell coefficients and Nagelkerke coefficients of 0.316 and 0.352, respectively, which indicates that the model was able to explain the variation in the original variables and that each of the alternatives complied with the assumption of uncorrelated independence, which means that each of the dependent variables was independent of each other. In conclusion, it meets the requirements for parameter estimation of the logit model.

Table 6.

Results of the likelihood ratio test.

Then, this study estimated the influential factors of individuals’ perceived preference for Kowloon Walled City Park using the maximum likelihood method. Variables with zero estimated parameters were omitted based on the Wald test, as presented in Table 7. Among them, the contemporary built-up area, historical relic area, and natural folklore area were set as the experimental group, and the ecological conservation area was set as the control group. The reason for this is that the ecological conservation area is an area that has been transformed according to a purely natural environment, which contrasts most sharply with other options, making it more suitable for the control group.

Table 7.

Results of regression analyses of the multinomial logit choice model.

Based on the results of the multinomial logit model regression, males have a higher preference for ecological conservation area, and the young and middle-aged groups aged 21–40 also have a higher preference for this area. This suggests that the young and middle-aged groups retain a higher preference for the natural environment in city parks, which reflects the rising living standards of the people in Hong Kong in recent years and their expectations for a better urban habitat. However, from another perspective, the young and middle-aged groups in Hong Kong consider the renovated Kowloon Walled City Park more as a tourist attraction, which means that they mainly appreciate the park as a scenic spot and put the functions of maintaining the park’s naturalness and ecological conservation above its historical and cultural functions, indicating that they have not taken into account the functions of the Kowloon Walled City Park in terms of historical heritage and cultural resources management. Furthermore, the academic qualifications do not affect the preferences of the interviewees. However, prior research has indicated that education is a reliable indicator of environmental issues, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of education tend to be more environmentally conscious [47], and this aspect remains to be further verified by this study in the future. In terms of occupations, company employees and freelancers have a greater preference for ecological conservation areas, whereas public officials have a greater preference for historical relic areas. It was learned from the interviews that government officials have stable jobs in public organizations, but they have relatively fixed daily schedules and limited leisure time, so they are less involved in recreational activities in ecological conservation areas. As the size of their families grows, the respondents will prefer historical relic areas, contemporary built-up areas, and ecological conservation areas, respectively, and this trend suggests that the respondents with larger families are more willing to enjoy the experiences in natural environments provided by urban parks, as well as family-based leisure and recreational activities. In terms of income, respondents with a monthly per capita income of HKD 15,000 and below generally prefer contemporary built-up areas, while those with a monthly per capita income of HKD 15,000 and above have a greater preference for ecological conservation zones, which is possibly due to the fact that the low-income group has relatively limited financial means, constraining their needs for a higher level of the natural landscape and ecological environments, but the middle and high-income groups usually do not have financial and survival pressures, so they are relatively more aware of the historical and cultural resources of the parks, and, thus, place more importance on the experience of natural environments in urban parks. Respondents who have resided in Hong Kong for less than five years prefer contemporary built-up areas, while those who have resided in Hong Kong for 5–10 years will prefer historical relic areas. This suggests that with a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of urban parks, there will also be a better understanding and appreciation of the history and culture of parks.

4. Discussion

Based on the landscape differences in the transformation process of urban parks, this study divided Hong Kong Kowloon Walled City Park into four types: contemporary built-up area; historical relics area; natural folk area; and ecological preservation area, and provided a comprehensive description and analysis of individual spatial perceptions and preferences, as well as further exploring the potential factors affecting the individual’s perceived preferences through a polynomial logit model. The results show that people’s perceived preferences for urban parks reflect their perceptions of the trade-offs between naturalness and sociability in park design. Specifically, different areas within the Kowloon Walled City Park differed in many characteristics, and people generally preferred park areas that integrated modern and traditional elements and natural and humanistic environments. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic may have accentuated the value of urban parks as essential community spaces, influencing user preferences toward areas that offer a balance between nature and safety, as well as opportunities for physical distancing and mental respite. This study contributes uniquely to the field by emphasizing how the integration of diverse park elements can enhance public satisfaction and environmental stewardship. Unlike previous research [48], which predominantly reaffirms these principles, our findings underscore nuanced distinctions across park zones and deepen understanding of visitor preferences.

Specifically, the results of the semantic differential analysis show that four areas within the Kowloon Walled City Park are differentiated in terms of many characteristics. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, these differences may have been further accentuated, with users placing a higher premium on natural and open spaces that allow for safe social interaction. In general, the perceptual differences between the various areas were large regarding spatial sense, color temperature, architectural style, artificial traces, and green cover, while the perceptual differences in terms of hue, cultural originality, and infrastructure were relatively small. Secondly, the perceptual preference analysis shows that respondents prefer park areas that integrate modern and traditional elements and natural and humanistic environments, which is the natural folklore area defined in this study. This preference may have been heightened by the pandemic, as users seeked out park spaces that offered a retreat from the confines of indoor environments. Similarly, the results of the IPA analysis show that respondents consider the natural folklore area and historical relic area to be very important, but their performance is not satisfactory and needs to be focused on restoration and improvement, whereas the contemporary built-up area and the ecological conservation area are of relatively low importance, but their performance is better, and making full use of these factors can have a more positive effect. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has also underscored the need for park spaces that can cater to the increased demand for outdoor activities while ensuring health and safety protocols are in place.

In addition, some studies suggest that certain IPA statistical evaluation criteria need to be followed, especially regarding the optimal classification of attributes in IPA, to standardize the use of IPA methods [49]. Again, the results of the influencing factors analysis show that factors such as gender, age, occupation, household size, per capita monthly income, and residence in Hong Kong affect the results of respondents’ preference choices for different areas within the Kowloon Walled City Park. The COVID-19 pandemic may also introduce new variables into this equation, such as health concerns and social distancing practices, which may now play a significant role in shaping user preferences. In particular, the middle and upper-income groups were more concerned with the experience of the city park as a natural landscape and ecological environment; meanwhile, larger household sizes were more likely to be engaged in the natural environment and enhanced their preference for natural areas. Such findings are new to this study and represent new features of the ongoing urbanization in Hong Kong. On this basis, this study needs to fully explain the detailed characteristics of different types of respondents in the future. For example, a study has previously noted that people with a deeper understanding of nature also prefer ecologically sustainable landscapes [50]. Therefore, exploring the deep-rooted reasons influencing people’s preferences and summarizing the relevant patterns will help to improve people’s understanding of the multiple and complex functions of urban parks, which will, in turn, increase the breadth and depth of their use of parks.

To broaden the scope and enhance the applicability of our findings, we conducted a comparative analysis of our results with other parks in close proximity to the study area. For instance, Sung Wong Toi Garden, with its historical significance and the preservation of cultural heritage, Hoi Sham Park, with its transformation from an island to a land-reclaimed area and its focus on community engagement, Olympic Garden, with its unique connection to the Olympic movement and its role as a melting pot of cultures, all offer different perspectives on park design and management. It revealed that while each park has its unique characteristics and design approach, the Kowloon Walled City Park stands out due to its successful integration of historical elements, lush greenery, and recreational facilities, which has been a model for urban renewal and heritage conservation. Revealing that the insights gleaned from this study are not only relevant to Hong Kong but also serve as a valuable reference for urban park development in similar international metropolises, this comparison highlights the importance of adapting park design to the specific cultural, historical, and ecological contexts of an area.

5. Conclusions

Based on the data collected through questionnaires and interviews, this study thoroughly analyzed respondents’ perceptions and preferences regarding the transformation of Kowloon Walled City into a modern urban park. Several methods have been adopted in this study. The semantic differential approach has shown the comparison of people’s perceptions of four representative areas of Kowloon Walled City in a quantitative way, revealing clear patterns in how respondents viewed the historical and modern aspects of the park spaces. Importance–performance analysis (IPA) revealed the extent to which people perceived the four areas as important and how they perform, highlighting specific areas for improvement that aligned with public expectations. The multivariate logit choice model provided information about the relationship between people’s perceived preferences for Kowloon Walled City Park and their individual characteristics, showing how demographics influenced feature park preferences. The findings indicate a general preference among respondents for park areas that blend modern and traditional elements, as well as natural and humanistic environments. Particularly noteworthy is the trade-off observed between naturalness and sociability in urban park design. Kowloon Walled City Park, representative of typical urban parks in Hong Kong, has undergone a significant transformation from a historical site to a multifaceted urban park, integrating various features associated with the park itself and its historical context. This transformation has also taken on new significance in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as urban parks are increasingly seen as vital for mental and physical health, in addition to their traditional roles. This study argues that the primary objective of urban parks is to adapt to evolving individual needs. The feedback from respondents reflects authentic public attitudes toward urban parks, providing a crucial foundation for enhancing urban park construction. Factors influencing individual preferences, such as occupation, family size, and economic status, underscore the importance of inclusive user involvement in park planning and policymaking.

Given the accelerating urbanization in China and the growing urban population, there is an increasing demand for elevated standards in city development. Urban parks play a pivotal role in signaling urban progress and harmonizing natural and social elements within the urban ecosystem. Theoretically, this study underscores the intrinsic value of urban parks as a cornerstone of sustainable urban development, advocating for a balance between ecological integrity and the needs of an expanding urban population. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the necessity for urban parks to serve as resilient spaces that can adapt to public health crises and support community well-being. Considering this study’s applicability, it is essential to take into account Hong Kong’s unique urban development and available resources, which exemplifies a successful fusion of urban advancement and ecological preservation, such as the typical case of Kowloon Walled City Park. From a practical standpoint, Hong Kong’s approach to integrating green spaces amidst high-density urban environments offers a blueprint for other cities facing similar challenges. The insights garnered from this study are pertinent not only to Hong Kong but also serve as a valuable reference for urban park development in similar international metropolises. The theoretical implications suggest that urban parks can act as a catalyst for community well-being and environmental stewardship on a global scale. The methodological approach combines perception-based surveys and landscape analysis and offers an innovative contribution to urban park research, providing actionable insights for designing and refining urban parks. These findings are instrumental for urban planners and policymakers aiming to create urban parks that offer substantial practical benefits, such as improving air quality, reducing urban heat island effects, and providing recreational spaces that enhance the quality of life for urban dwellers. These findings are instrumental for urban planners and policymakers aiming to create urban parks that offer substantial practical benefits. Future research could further enrich these insights by focusing on specific aspects of urban park design and employing targeted methodologies to achieve more comprehensive and precise conclusions.Above all, this study endeavors to underscore the profound societal and ecological contributions of urban parks, aiming to explore practical urban park designs that can furnish valuable insights for planners, developers, and government officials. However, it must be noted that this research is circumscribed by several limitations. First, this study’s focus on Kowloon Walled City Park may limit the generalizability of the findings to other urban park contexts. The unique historical and cultural significance of the park, as well as its specific spatial configuration, may not be representative of other urban parks. On the other hand, this study also acknowledges its limitations in not comprehensively examining a wider range of demographic factors and relying exclusively on quantitative research methods. The sample size, while sufficient for the scope of this study, may not capture the full diversity of park users, which could affect the external validity of the results. Furthermore, the questionnaire-based data collection method may not fully capture the nuanced and subjective experiences of park users.

To sum up, future studies are encouraged to expand the comparative analysis to encompass a greater number of parks across diverse urban settings, thereby reinforcing the generalizability of our findings and their applicability to a wider array of urban park development contexts. This could involve a more inclusive approach to data collection, such as incorporating qualitative methods like interviews or focus groups to delve deeper into user experiences. This expansion will not only validate our insights but also provide a more comprehensive understanding of user experiences and preferences, which are crucial for the development of park design strategies that are responsive to the evolving needs of urban communities and the pursuit of environmental sustainability goals. Moreover, investigating the interplay between demographic variables and spatial preferences could yield more tailored and equitable park design recommendations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D., Z.C. (Zimeng Chen), T.D. and Z.Z.; methodology, S.D., Y.H.; investigation, S.D., Z.C. (Zimeng Chen), Z.R., T.D. and Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D., Z.R. and Z.C. (Zejin Chen); writing—review and editing and validation, Z.R., T.D., Y.H. and Z.Z.; resources and funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (23CGL046), the Development Research Center of the State Forestry and Grassland Administration (JYC-2023-0030), and the Shanghai Normal University of Humanities and Social Sciences Research Youth Interdisciplinary Innovation Team Cultivation Project (310-AWO203-23-005411).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study were sourced from empirical research carried out by the research group, which was funded by the Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Culture and Tourism and the Development Research Center of the State Forestry and Grassland Administration. Detailed information regarding the funding can be found in the Funding section of this study. The research group possessed the necessary rights to utilize the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The sponsors providing funding did not partake in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Questionnaire on User’s Spatial Perceived Preferences of Kowloon Walled City Park

Place of investigation (filled in by investigator):

Please provide your personal basic information. (Please fill in the number of the corresponding option in the box)

| Item | 1. Gender | 2. Age | 3. Education Status | 4. Occupation |

| Options | 1 = Male 2 = Female | 1 = 20 years old and below 2 = 21–40 years old 3 = 40 years old and above | 1 = Primary school and below 2 = Middle school 3 = High school 4 = Bachelor 5 = Postgraduate and above | 1 = Corporate employee 2 = Government officer 3 = Freelance 4 = Retired and students |

| Your choice | ||||

| Item | 5. Family Size | 6. Per Capita Monthly Income | 7. Residence in Hong Kong | |

| Options | 1 = 1 person 2 = 2 persons 3 = 3 persons 4 = 4 persons and above | 1 = 150,00 HKD and below 2 = 15,001–20,000 HKD 3 = 20,001–250,00 HKD 4 = 25,000 HKD and above | 1 = 5 years and below 2 = 5–10 years 3 = More than 10 years | |

| Your choice |

How do you rate the elements of Kowloon Walled City Park?

| Variable | Your Score (Please Tick the Corresponding Numbers) | Definition | ||

| Orderliness | Disorderly | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Orderly | The degree of neatness and orderliness |

| Spatiality | Closed | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Wide | The spaciousness and density |

| Hue | Dark | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Clear | Brightness and contrast |

| Color temperature | Cold | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Warm | Overall color tone |

| Physical originality | Weak | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Strong | The degree of preservation of the physical authenticity |

| Cultural authenticity | Weak | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Strong | The degree of preservation of cultural authenticity |

| Architectural style | Modern | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Traditional | The tendency of the park’s architectural style |

| Artificial traces | Light | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Heavy | The degree of artificial modification of the park’s interior |

| Infrastructure | Poor | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Good | The degree of improvement of the park’s infrastructure |

| Green Cover | Low | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | High | The degree of the park’s green coverage |

| Sense of belonging | Unfamiliar | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Familiar | The degree of belonging to and familiarity with the park |

| Sense of security | Dangerous | −2 −1 0 +1 +2 | Safe | The degree of security and management |

| Note: The evaluation scale was classified into five levels with five intervals between each adjective combination. The interval values were −2, −1, 0, 1, and 2 from left to right, and these were used as the scoring methods for evaluations. The higher the score of each evaluation item, the more inclined the evaluation factor is to the right-hand adjective; the lower the score, the more inclined the evaluation factor is to the left-hand adjective. | ||||

What is your preference for Kowloon Walled City Park? And how do you evaluate the importance and performance of it?

| Park Area | Contemporary Built-Up Area | Historical Relic Area | Natural Folklore Area | Ecological Conservation Area |

| Your favorite type of park area (One choice out of four; please check the box corresponding to the option) | ||||

| Comprehensive evaluation (Please fill in the number of the corresponding option in the box: 1 = Poor; 2 = Fair; 3 = Good; 4 = Very Good; 5 = Excellent) | ||||

| Importance rating (Please fill in the number of the corresponding option in the box: 1 = Not at All Important; 2 = Somewhat Unimportant; 3 = Neutral; 4 = Somewhat Important; 5 = Extremely Important) | ||||

| Performance rating (Please fill in the number of the corresponding option in the box: 1 = Poor; 2 = Fair; 3 = Good; 4 = Very Good; 5 = Excellent) |

References

- Allen, G.L. The organization of route knowledge. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 1982, 15, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.L.; Kirasic, K.C. Effects of the cognitive organization of route knowledge on judgments of macrospatial distance. Mem. Cogn. 1985, 13, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipitone, J.M.; Jović, S. Urban green equity and COVID-19: Effects on park use and sense of belonging in New York City. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri, Z.; Mashhadi, A.; Timme, M.; Ghanbarnejad, F. Recreational mobility prior and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Commun. Phys. 2024, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, K. Historical redlining and park use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from big mobility data. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2024, 34, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irga, P.J.; Burchett, M.D.; Torpy, F.R. Does urban forestry have a quantitative effect on ambient air quality in an urban environment? Atmos. Environ. 2015, 120, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.H.; Nicholas, K.A. Introducing urban food forestry: A multifunctional approach to increase food security and provide ecosystem services. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 1649–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pierskallab, C. Using contingent valuation to estimate the willingness of tourists to pay for urban forests: A study in Savannah, Georgia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khataza, R. Preferences for urban greenspace functions during public health pandemics. Empirical evidence from Malawi. Urban. Sustain. Soc. 2024, 1, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pröbstl-Haider, U.; Gugerell, K.; Maruthaveeran, S. COVID-19 and outdoor recreation–lessons learned? Introduction to the special issue on “outdoor recreation and COVID-19: Its effects on people, parks and landscapes”. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 41, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoić, S.K. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: An international exploratory study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J.E.; Nowak, D.J.; Watson, G.W. Future directions for urban forestry research in the United States. J. Arboric. 2002, 28, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The role of nature in the context of the workplace. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1993, 26, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode, A.; Fry, G.L.A. Visual aspects in urban woodland management. Urban For. Urban Green. 2002, 1, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S. Wilderness & the American Mind. Kenyon Rev. 2001, 23, 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wolfing, S.; Fuhrer, U. Environmental attitude and ecological behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Brindley, P.G.; Lange, E. Comparison of urban green space usage and preferences: A case study approach of China and the UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 249, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, J.B. Ecology of Hierarchical Landscapes: From Theory to Application; Chen, J., Saunders, S.C., Brosofske, K.D., Crow, T.R., Eds.; Nova Science Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes End Values; Prentice-Hall Inc.: Engtewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, T. American Green-the Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Lawn; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, P.; Birkenholtz, T. Turfgrass revolution: Measuring the expansion of the American lawn. Land. Use. Pol. 2003, 20, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A. Are health benefits of physical activity in natural environments used in primary care by general practitioners in The Netherlands? Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Messy ecosystems, orderly frames. Landsc. J. 1995, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.A. Landscape water use in phoenix. Desert Plants 2001, 17, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczyńska, M. Present security of the neighborhood urban parks considering SARS-CoV-2 potential spreading–A case study in Ursynów district in Warsaw. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum. 2022, 21, 355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, S.D.; Highfield, W.; Alston, L. Does location matter? Measuring environmental perceptions of creeks in two San Antonio watersheds. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han KeTsung, H.K. The effect of nature and physical activity on emotions and attention while engaging in green exercise. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 24, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shen, J.; Wen, Y. Residents’ Spatial Image Perception of Urban Green Space through Cognitive Mapping: The Case of Beijing, China. Forests 2021, 12, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Preference to home landscape: Wildness or neatness? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 99, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, R.; Straits, B.C. Approaches to Social Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; p. 244. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, N.J.; Campbell, N.; Laurent, A. In Search of Appropriate Methodology: From Outside the People’s Republic of China Looking In. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1989, 20, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Z.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.J. Spatial Distribution of Residential Space and Residents’ Residential Space Preferences in Beijing. Geogr. Res. 2003, 22, 751–759. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Han, X.; He, J.; Jung, T. Measuring residents’ perceptions of city streets to inform better street planning through deep learning and space syntax. ISPRS 2022, 190, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.K.L.; Yung, C.C.Y.; Tan, Z. Usage and perception of urban green space of older adults in the high-density city of Hong Kong. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Wei, S.M.; Yao, R. A study on the division of garden space types and quantification of landscape perceptual characteristics. J. Northwest For. Coll. 2012, 27, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Llinares, C.; Page, A. Application of product differential semantics to quantify purchaser perceptions in housing assessment. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2488–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Research on Urban Spatial Perception Based on SD Method; Tongji University: Shanghai, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. A study on the spatial perception of Shanghai streets based on the semantic difference method. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 39, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.X.; Shao, L.; Lin, Y.Y. Differences in spatial perception of towns between foreign tourists and locals—A case study of western towns in Nanhai District, Foshan City, Guangdong Province. Tour. Sci. 2013, 27, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Xu, H.; Sun, H. Spatial Patterns and Multi-Dimensional Impact Analysis of Urban Street Quality Perception under Multi-Source Data: A Case Study of Wuchang District in Wuhan, China. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.W.; Mak, C.M.; Wong, H.M. Effects of environmental sound quality on soundscape preference in a public urban space. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 171, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A.; Maghrabi, A.; Goldblatt, R. Public open spaces evaluation using importance-performance analysis (IPA) in Saudi Universities: The case of King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah. Sustainability 2021, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, T.O. Adopting Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) model to assess land governance in the peri-urban areas of Ibadan, Nigeria. Land Use Policy 2023, 133, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abello, R.P.; Bernaldez, F.G. Landscape preference and personality. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1986, 13, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, M.P.; Ward, M.P. Ecology: Let’s hear from the people: An objective scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcury, T.A.; Scollay, S.J.; Johnson, T.P. Public Environmental Knowledge: A Statewide Survey. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. General versus specific environmental concern: A Western Canadian case. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribe, R.G. The aesthetics of forestry: What has empirical preference research taught us? Environ. Manag. 1989, 13, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, I. Importance-performance analysis: A valid management tool? Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, A.; Baker, D. Standing for where you sit: An exploratory analysis of the relationship between academic major and environment beliefs. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).