Abstract

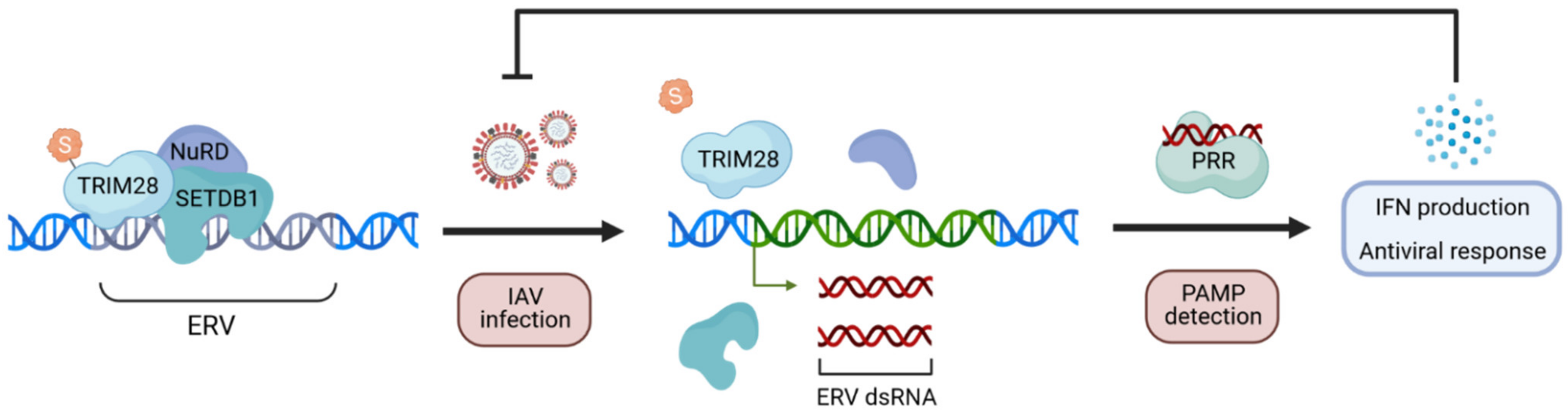

SUMOylation is a highly dynamic ubiquitin-like post-translational modification that is essential for cells to respond to and resolve various genotoxic and proteotoxic stresses. Virus infections also constitute a considerable stress scenario for cells, and recent research has started to uncover the diverse roles of SUMOylation in regulating virus replication, not least by impacting antiviral defenses. Here, we review some of the key findings of this virus-host interplay, and discuss the increasingly important contribution that large-scale, unbiased, proteomic methodologies are making to discoveries in this field. We highlight the latest proteomic technologies that have been specifically developed to understand SUMOylation dynamics in response to cellular stresses, and comment on how these techniques might be best applied to dissect the biology of SUMOylation during innate immunity. Furthermore, we showcase a selection of studies that have already used SUMO proteomics to reveal novel aspects of host innate defense against viruses, such as functional cross-talk between SUMO proteins and other ubiquitin-like modifiers, viral antagonism of SUMO-modified antiviral restriction factors, and an infection-triggered SUMO-switch that releases endogenous retroelement RNAs to stimulate antiviral interferon responses. Future research in this area has the potential to provide new and diverse mechanistic insights into host immune defenses.

1. General Overview of SUMOylation and the SUMO Machinery

Since their discovery in 1996 [1], the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins have emerged as key post-translational modifiers associated with crucial regulatory roles in the cell. SUMO proteins are small polypeptides of around 12 kDa that can be covalently conjugated to specific lysine residues on target proteins through a process called SUMOylation, thus altering target protein localization, stability, and/or interactions with other macromolecules. As such, SUMOylation plays an essential role in several cellular processes, including DNA damage repair responses, chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, and signal transduction [2]. SUMO proteins are highly conserved across all eukaryotes, and to date, five genes encoding potential SUMO paralogs have been identified in humans. SUMO1, 2 and 3 are ubiquitously expressed, and have been the most extensively studied [2]. SUMO2 and 3 are very similar to one another, sharing 97% sequence identity, whereas SUMO1 shares only 47% identity with SUMO2/3 [3].

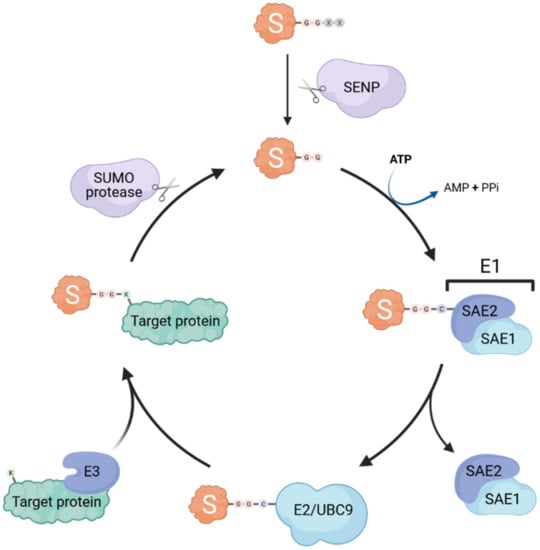

Similar to ubiquitination, SUMOylation occurs through the sequential action of E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases (summarized in Figure 1). Interestingly, only a single E1 (heterodimeric SAE1/SAE2) and E2 (UBC9) exist, whereas several SUMO E3 ligases have been identified (e.g., some TRIM proteins, RANBP2, and PIAS proteins) [4,5,6]. Thus, it is likely that the E3 ligases are the main actors conferring substrate specificity and SUMO paralog selection [7]. SUMO proteins are expressed as precursors that require a proteolytic maturation step before SUMOylation can occur: sentrin-specific proteases (SENPs) cleave the SUMO precursor’s C-terminal tail to expose the diglycine motif essential for subsequent conjugation [8,9]. The E1 activating enzyme then forms a thioester bond between its catalytic cysteine and the terminal glycine of mature SUMO in an ATP-dependent reaction, before transferring the SUMO adenylate to the E2 SUMO-conjugating enzyme UBC9 [10]. The SUMO protein is then further transferred by UBC9 to an acceptor lysine of the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond between the carboxyl group of the C-terminal glycine residue of SUMO and the ε-amino group of the lysine side chain. The target lysine is typically located in a specific consensus motif ψKxD/E (where ψ is a hydrophobic residue, x is any amino acid), that has been identified in more than half of all known SUMO target proteins [11]. This process is usually facilitated by SUMO E3 ligases that catalyze the transfer of SUMO from UBC9 onto the target, however, E3-independent SUMOylation has also been observed [12].

Figure 1.

The SUMOylation machinery. Small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMOs; S in the cartoon) are covalently attached to lysine (K) residues in target proteins through the concerted action of dimeric E1 activating enzymes (SAE1/SAE2) and an E2 conjugating enzyme (UBC9). SUMOylation is usually aided by specific SUMO E3 ligases. SUMO specific proteases (e.g., SENP family members) can de-conjugate SUMO from its targets (known as deSUMOylation) and are also essential for the proteolytic maturation of SUMO precursors by cleaving off C-terminal residues to expose the di-glycine motif that is necessary for conjugation.

Notably, SUMO2 and SUMO3 contain internal lysines that can serve as SUMO acceptor sites themselves, thus permitting the formation of polySUMO chains [2]. The formation of SUMO chains is promoted by specific SUMO E3 ligases that also carry SUMO E4 elongase activity, such as ZNF451 family members [13]. SUMO chains increase the functional diversity of SUMO modification, as many consequences of SUMOylation include the recruitment of specific SUMO-interacting motif (SIM)-containing proteins, which thereby nucleate multi-molecular signaling complexes, or trigger changes in localization or protein stability [14]. For example, SIM-containing SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbL) can be recruited to SUMOylated targets and result in ubiquitination of SUMO chain-containing proteins, thus marking them for proteasome-mediated degradation [15].

Importantly, the SUMOylation process is also reversible, and counteracted by various SUMO-specific proteases, which are divided into three classes based on the fold of their respective catalytic domains: ubiquitin-like protease/sentrin-specific protease (Ulp/SENP) family, the deSUMOylating isopeptidase (Desi) family, and ubiquitin-specific peptidase-like protein 1 (USPL1) [16]. These proteases are able to cleave the isopeptide bond between SUMO and its substrates. Thus, SUMOylation is a highly dynamic mechanism by which the cell can quickly regulate numerous functional pathways, most notably under various stress conditions, without altering protein synthesis [17].

3. Strategies and Technologies to Identify SUMOylated Proteins

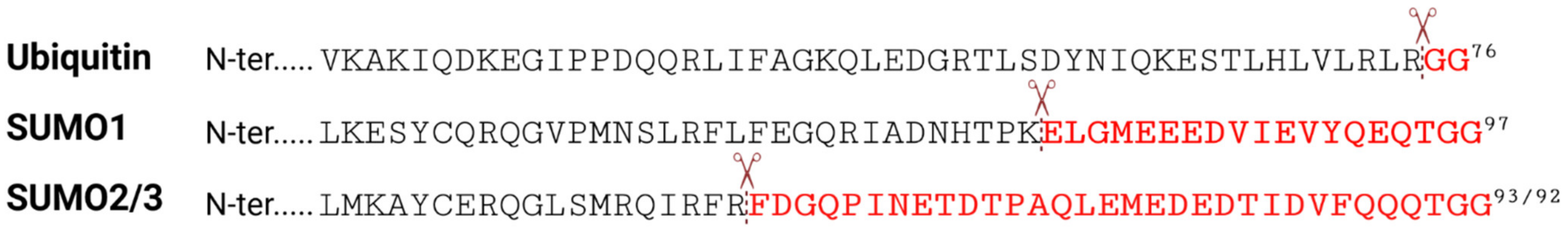

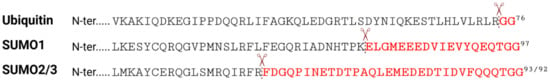

Given the contribution of SUMOylation to the regulation of innate antiviral immune responses, there has been a substantial research interest in identifying, and functionally characterizing, protein targets that change in SUMO-modification status in response to the stress of virus infection. However, as discussed above, most studies to date have mainly relied on targeted analysis of specific known proteins of interest that had already been implicated in certain pathways, and their SUMOylation status was investigated by standard techniques such as overexpression (sometimes together with components of the SUMO machinery), immunoprecipitation, and western blotting. These methods usually limit analyses to only a single protein at a time, and thus it could be of great benefit to adopt less biased approaches that can identify SUMOylated proteins (preferably expressed under endogenous conditions) at a system-wide scale. MS-based proteomics allow for direct mapping and quantification of numerous post-translational modifications (PTMs), and covalent modifications often result in mass changes to modified peptides that can be directly detected [42]. This enables the identification of modified proteins and mapping of the specific modified residue, as well as determination of changes in abundance if methods such as Label Free Quantification (LFQ) or Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) are employed [43]. Nevertheless, efficient large-scale analysis of specific PTMs requires prior enrichment of modified peptides. For example, tryptic digest of ubiquitinated proteins results in peptides containing a diglycine (GG) remnant from the two C-terminal glycine residues of the conjugated ubiquitin on the modified lysine (K) (Figure 2). A specific antibody raised against this K-ε-GG motif was generated to enrich for ubiquitin-modified peptides prior to MS, creating a highly efficient enrichment strategy that is widely applied to investigate endogenous ubiquitination [44]. In contrast, MS-based identification of SUMO substrates and SUMOylation sites has proved a lot more challenging. Tryptic digest of SUMOylated proteins leaves a larger signature tag on modified peptides (19 or 32 amino acids for mammalian SUMO1 or SUMO2/3, respectively (Figure 2)) that interferes with their identification due to complex MS/MS fragmentation patterns [11]. In addition, many proteins that can be SUMO-modified appear to have a very low abundance in the cell, and only a small percentage of these proteins are modified at any one time [45]. Furthermore, the deSUMOylation activity of SUMO proteases is rather high in cell lysates, resulting in rapid loss of SUMOylation unless preventative steps are taken [46]. These peculiarities of the SUMO system have sometimes hampered general efforts to identify SUMOylated proteins (as compared with ubiquitinated proteins), and therefore new methodologies and procedures have had to be developed, although each of these technologies also has caveats.

Figure 2.

The C-terminal amino-acid sequences of ubiquitin and SUMO paralogs. Scissors indicate trypsin cleavage sites. Amino acid remnants that remain on UBL-modified peptides after tryptic digest are highlighted in red.

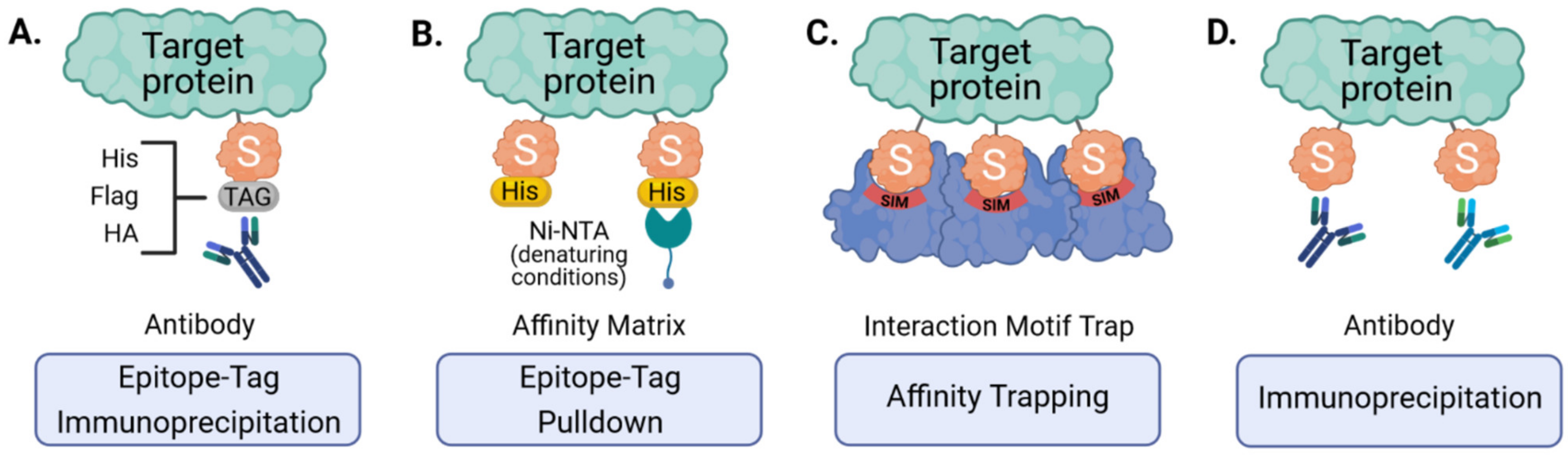

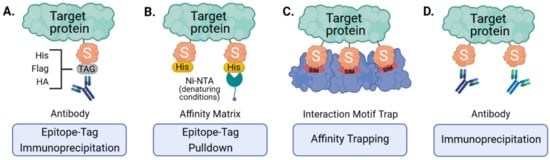

3.1. Epitope-Tagging to Assist Purification of SUMO-Modified Proteins

To facilitate enrichment of SUMO conjugates prior to trypsin digest and MS, several groups have made use of ectopically expressed epitope-tagged SUMOs (Figure 3A,B). These affinity tags commonly include polyhistidine- (His6), Flag-, HA- or Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP)- tags that are small enough to permit SUMO conjugation and function, but allow for efficient purification at high yields [47,48,49,50,51,52]. High stringency purification of tagged SUMOs is achieved by the strong interaction between certain tags and their corresponding affinity matrices (e.g., His and Ni-NTA) that can allow for denaturing cell lysis and harsh washing conditions, and is essential to inactivate SUMO proteases and to dissociate proteins interacting non-covalently [51,52]. Such methods can be important for minimizing the likelihood of detecting false-positive SUMO substrates, and are particularly powerful when combined with ‘slice-by-slice’ analyses, where purified proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE alongside corresponding total cell lysates, and the resulting MS data from individual gel slices are interpreted to validate SUMO-associated mass shifts [33,47,49]. Ectopic expression of epitope-tagged SUMOs followed by purification and MS has therefore proven a useful tool, as it has been successful in identifying more than a thousand candidate SUMO targets, although a major caveat is that it is unable to give information on the specific site of SUMO modification [38], which is critical for follow-up studies. Our laboratory has also found that this method may not be ideal for identifying SUMO paralog-specific substrates, as experiments using overexpressed TAP-tagged SUMO1 or SUMO2 unexpectedly yielded similar SUMO target profiles [33]. Furthermore, and with respect to innate antiviral immunity, recent studies have also shown that ectopic expression of SUMO3 results in lower STAT1 activation in response to IFNα [35], providing yet more evidence that SUMO overexpression may unintentionally bias results. In addition, most of these techniques only allow analysis of one SUMO paralog at a time. SUMO overexpression also excludes the investigation of endogenous SUMOylation responses, particularly in in vivo tissues. Therefore, in an attempt to study SUMOylation in a more physiological way, genetic engineering has been used to generate knock-in mice with epitope-tagged SUMO [50]. The advantage is that SUMO is expressed at close-to-endogenous levels, which lowers the risk of overexpression artefacts, and SUMOylation can be studied in different tissues. Thus, while epitope tagging and denaturing purification is no doubt an important technology for identifying SUMOylated proteins, future applications, particularly in cell models, should consider the use of gene-editing strategies to tag endogenous SUMOs and thereby ensure appropriate expression levels [53].

Figure 3.

Strategies for the enrichment of SUMOylated target proteins. Ectopically expressed, epitope-tagged SUMO can be purified using tag-specific antibodies (A) or affinity matrices that bind specific tags (e.g., His6-tag and Ni-NTA under denaturing conditions) (B). Endogenous SUMO can also be enriched by engineered SUMO-traps that consist of multiple SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) immobilized onto an affinity matrix (C) or by immunoaffinity purification using SUMO-specific antibodies (D).

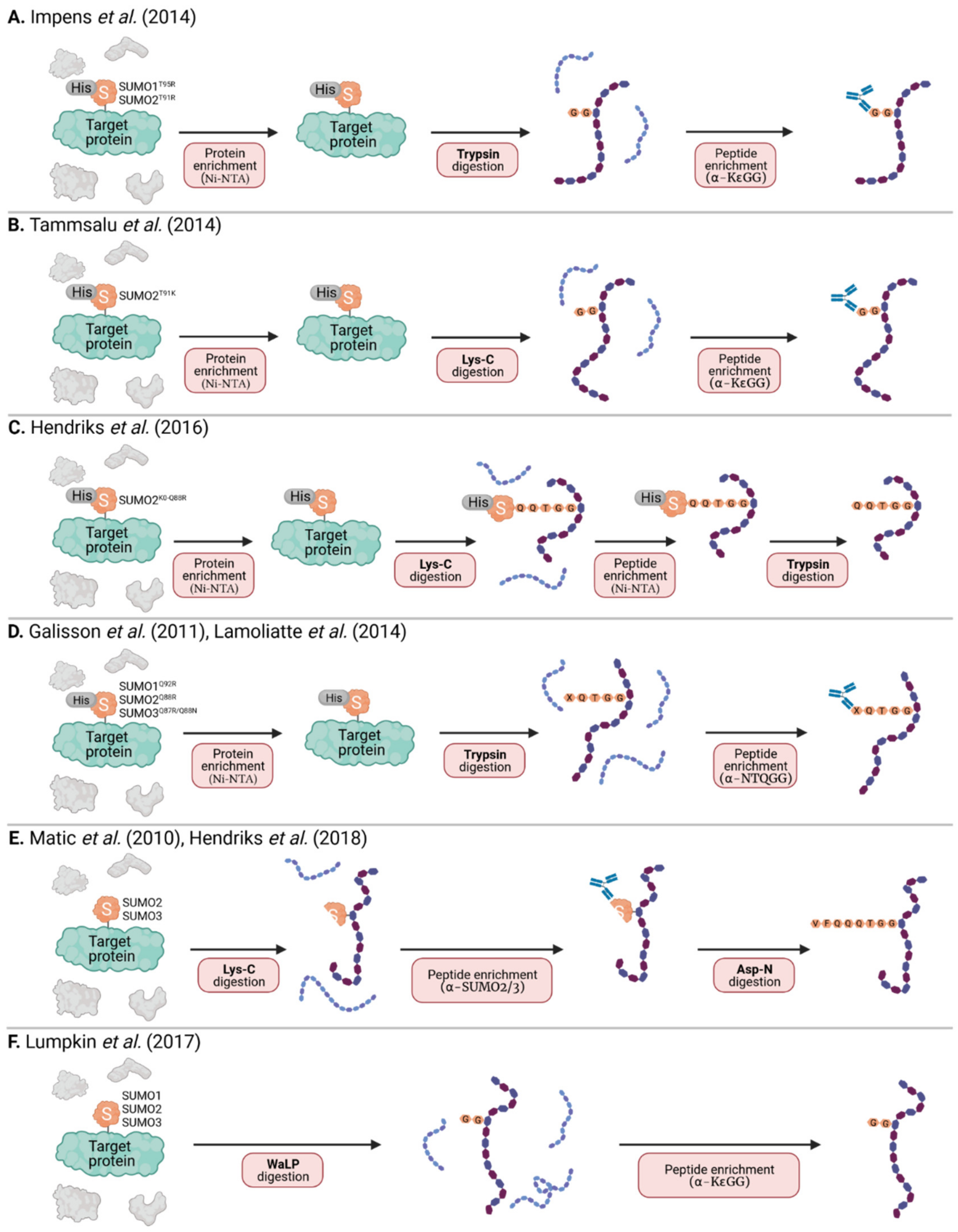

3.2. Re-Engineering SUMO to Identify Sites of Modification on Target Proteins

As stated above, tryptic digest (most commonly used in MS) of SUMOylated proteins leaves a large signature tag on modified peptides that interferes with their identification. This is not an issue with ubiquitin due to the presence of an arginine residue immediately preceding its C-terminal di-glycine motif, forming a trypsin cleavage site that leaves only a small remnant on modified peptides. In SUMO paralogs, the C-terminal di-glycine sequence is preceded by threonine, and there is no other tryptic cleavage site near its C-terminus (Figure 2). To overcome this problem, strategic mutations were introduced into the SUMO sequence to result in more convenient tryptic cleavage fragments. Impens et al. generated His6-tagged versions of SUMO1 and SUMO2 with an arginine residue immediately before the C-terminal di-glycine motif (SUMO1 T95R and SUMO2 T91R) imitating the sequence of human ubiquitin (Figure 2 and Figure 4A) [54]. Peptides containing this di-glycine remnant after trypsin digest could then be purified using the K-ε-GG immunoaffinity enrichment pipeline established for ubiquitinated proteins, and processed to identify sites of diglycine modification on target proteins. Unfortunately, this approach does not differentiate between the tryptic di-glycine remnant derived from the mutant SUMO and the diglycine remnant from other ubiquitin-like modifiers (UBLs), including ubiquitin, ISG15 and NEDD8. Thus, this method still requires expression of epitope-tagged SUMO, and the prior purification of SUMO conjugates before preparation of tryptic peptides.

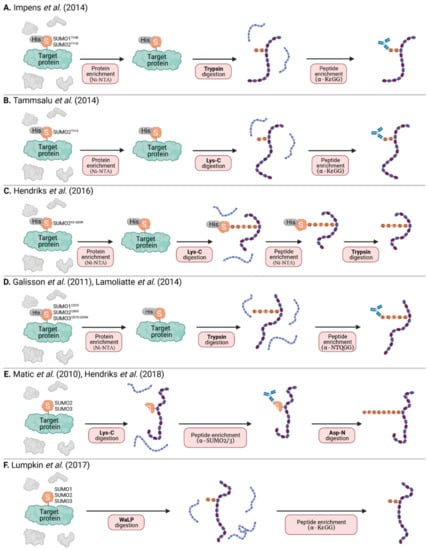

Figure 4.

MS-based strategies to identify specific SUMOylation sites. (A) His6-SUMO1-T95R or HisSUMO2-T91R modified proteins are purified by Ni-NTA, digested with trypsin, and peptides containing the di-glycine remnant are enriched using a specific α-KεGG antibody. (B) His6-SUMO2 T91K modified proteins are purified by Ni-NTA, digested with Lys-C, and peptides containing the diglycine remnant are enriched using a specific α-KεGG antibody. (C) Proteins modified with His10-SUMO2-K0-Q88R (K0 = all K residues mutated to R) are purified by Ni-NTA and digested with Lys-C. Peptides containing the intact His10-SUMO modification are then enriched by a second Ni-NTA purification step before trypsin digest. (D) His6-SUMO1 Q92R, His6-SUMO2 Q88R and His6-SUMO3 QQ87/88RN modified proteins are purified by Ni-NTA, digested with trypsin, and peptides containing a (X)QTGG remnant are enriched using a specific α-NQTGG antibody. (E) Target proteins modified with endogenous SUMO are digested with Lys-C. Peptides containing a SUMO fragment (with the intact SUMO2/3 antibody epitope) are then immunoaffinity-purified before a second digestion step with Asp-N. (F) Target proteins modified with endogenous SUMO are digested with the endoproteinase WaLP, and peptides containing the di-glycine remnant are enriched using a specific α-KεGG antibody. For all methods (A–F), enriched peptides are analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS) for identification and quantification.

A further caveat arises when one considers the possibility that a particular SUMO-modified protein may also be ubiquitinated, therefore this method may still map both SUMOylation and ubiquitination sites in some proteins. To overcome this, Tammsalu et al. took advantage of the enzymatic specificity of the endoproteinase, Lys-C, which only cleaves at the C-terminal side of lysines unlike trypsin that also cleaves at the C-terminal side of arginine residues [55]. Thus, Tammsalu et al. substituted the threonine near the SUMO2 C-terminus to lysine (His6-SUMO2-T91K) generating a novel Lys-C cleavage site that also results in the di-glycine remnant on modified peptides, and which can be recognized by the K-ε-GG antibody for purification prior to MS (Figure 4B). Importantly, in this scenario, Lys-C (unlike trypsin) would not cleave other UBLs to reveal di-glycine remnants, thus ensuring that subsequent MS of purified peptides reveals di-glycine modification sites specific to SUMO, and not other UBLs [55]. For clarification, Tammsalu et al. (as well as some of the subsequent authors) based their studies on the SUMO amino acid sequences described by Tatham et al. [56], which were cloned from HeLa cells and differ from the SUMO sequence found on Uniprot by a few amino acids. Therefore, Tammsalu et al. refer to the SUMO2 mutant they generated as T90K [55].

Overall, methods to provide site-specific mapping of SUMO conjugates in target proteins creates a very rich additional layer of information as compared to only identifying SUMO target proteins. This information immediately opens up the possibility of functional experiments where specific SUMO modification sites can be altered in target proteins to assess mechanistic consequences.

In a further development of the SUMO mutagenesis strategies, Matic and colleagues used a His6-tagged SUMO2 mutant in which all lysines were replaced by arginines (K0: making it resistant to cleavage by the protease Lys-C), and introduced additional arginines at positions 91 (T91R) or 88 (Q88R), the positions that correspond to arginines in ubiquitin or the yeast SUMO protein, Smt3 [11,57]. After Lys-C digest of total protein lysates, peptides covalently bound to the intact His6-SUMO2 were purified by Ni-NTA via the His6-Tag, and digested with trypsin to leave either a diglycine (His6-SUMO2 K0 T91R) or QQTGG (His6-SUMO2 K0 Q88R) SUMO signature peptide that is suitable for MS analysis. This K0 method was further optimized using a two-step purification strategy, where primary Ni-NTA purification of His10-SUMO2 K0 Q88R, which enriches for His10-SUMO conjugated proteins, is followed by Lys-C digest and a second Ni-NTA purification step to enrich SUMOylated peptides prior to trypsin digest and MS (Figure 4C) [58]. One caveat of the K0 technique is that the absence of lysines precludes the formation of polySUMO chains. Galisson et al. generated mutants of the three SUMO paralogs with an N-terminal His6 tag and a tryptic cleavage site near the C-terminus (His6-SUMO1 Q92R, His6-SUMO2 Q88R and His6-SUMO3 QQ87/88RN) resulting in a unique five amino-acid SUMO fragment (EQTGG for SUMO1, QQTGG for SUMO2, NQTGG for SUMO3) on modified lysines upon tryptic digestion (Figure 4D) [59]. The short amino-acid SUMO remnant facilitates the identification of SUMOylated peptides by conventional database search engines and enables the distinction of individual SUMO paralogs by mass-specific signature fragment ions. Furthermore, Lamoliatte et al. generated a highly selective monoclonal antibody (α-NQTGG) that specifically recognizes peptides containing either of these SUMO remnants, enabling further immunoaffinity enrichment analogous to the K-ε-GG antibody used for ubiquitin-remnant enrichment (Figure 4D) [60]. Thus far, the K0 method has proven to be one of the most efficient strategies allowing for routine identification of more than 1000 SUMO2 sites under standard conditions [38]. However, given that this system is limited to mono-SUMO2 modification, the approach developed by Galisson et al. and Lamoliatte et al., which features all the strengths of ubiquitin remnant profiling, might become increasingly popular.

3.3. Purifying and Identifying Endogenous SUMOylated Proteins

The above-described MS-based proteomic approaches have enabled effective mapping of SUMOylation sites. However, all require expression of exogenous SUMOs carrying epitope tags or mutations in the SUMO sequence, which might result in unnatural SUMO conjugation and potentially detrimental consequences for signal transduction. To address this, several techniques have now been developed that are directed towards the identification of endogenous SUMOylated proteins. In analogy to tandem-repeated ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs), containing four tandem ubiquitin binding domains connected by flexible linkers and fused to an affinity tag [61], the high affinity interaction between SUMO and SIMs can be exploited to isolate potential SUMO targets (Figure 3C). A fragment of RNF4 (residues 32–133) containing its four SIM domains immobilized onto an affinity matrix was used to efficiently purify endogenous polySUMO2/3 chains and attached proteins [62]. To increase SUMO-binding capacity, another group generated SUMO-traps (SUBEs: SUMO binding entities) containing four tandem SIM2-SIM3 motifs from RNF4 fused to a GST or biotin tag [63,64]. One drawback of using these SUMO traps is the limitation to polySUMOylation, as generally monoSUMOylated substrates are not bound by these matrices with high affinity. Furthermore, high-stringency or denaturing conditions cannot be used to limit the co-purification of non-covalently bound proteins, as these conditions could disrupt the SUMO-SIM interactions.

Immunoprecipitation with specific monoclonal antibodies recognizing endogenous SUMO1 or SUMO2/3 has also been used for efficient enrichment and identification of endogenous SUMO targets in mammalian cells and complex tissues (Figure 3D) [65]. To minimize non-specific interactions, proteins can be selectively eluted using minimal epitope-spanning peptides. Still, the use of antibodies for enrichment provides relatively low yields, and also requires mild buffer conditions resulting in a high amount of background and/or the co-purification of non-covalently bound proteins. Furthermore, although these ‘endogenous’ approaches have led to the identification of a few hundred putative SUMO target proteins, no SUMOylation sites on these proteins have been reported, as the tryptic remnants of SUMO modification are not suitable for MS-based identification (see above and Figure 2). To overcome this issue, and to enable the enrichment of SUMOylated peptides, this antibody–based affinity purification method was revised and further optimized by Hendriks et al. (Figure 4E) [66]. Total cell lysates were first digested with Lys-C, which leaves intact a specific antibody epitope of SUMO2/3, thus allowing for efficient antibody-based purification of peptides containing the remaining SUMO2/3-fragment. To generate smaller peptides suitable for MS, a second digest with the endoproteinase Asp-N enzyme is then performed, which cleaves after aspartic acid residues. The resulting peptides contain an eight amino acid stretch (VFQQQTGG) covalently attached to the modified lysine residue of a peptide. Using this approach, roughly 15,000 unique endogenous SUMO2/3 sites were identified in cultured cells [66]. As this technique does not require ectopic expression or genetic manipulation, it has also been utilized to analyze in vivo SUMOylation, identifying almost 2000 SUMO2/3 sites across several mouse organs.

Also aiming at the identification of endogenous SUMO sites at a system-wide scale, Lumpkin et al. made use of a wild-type α-lytic protease (WaLP), which has a relatively relaxed specificity, but was shown to preferentially cleave following threonine residues, and rarely after arginine (Figure 4F) [67]. Thus, WaLP cleaves all SUMO paralogs at their C-terminal TGG sequences, resulting in a SUMO-remnant KGG on SUMO-modified peptides. These peptides are suitable for enrichment by the K-ε-GG-affinity purification workflow already described for ubiquitin profiling [44], and because the samples are generated with WaLP, they should contain few ubiquitin-derived GG remnant peptides. Strikingly, with this technique, one sample can be analyzed for ubiquitinated and SUMOylated targets in parallel by splitting the sample into two fractions and subjecting each to either trypsin or WaLP digestion. One shortcoming, however, is that WaLP can also cleave after leucine (and to some extent after isoleucine) and hence does not exclude the possible detection of FAT10ylated and FUB1ylated proteins.

3.4. Purifying and Identifying Interactors of SUMOylated Proteins

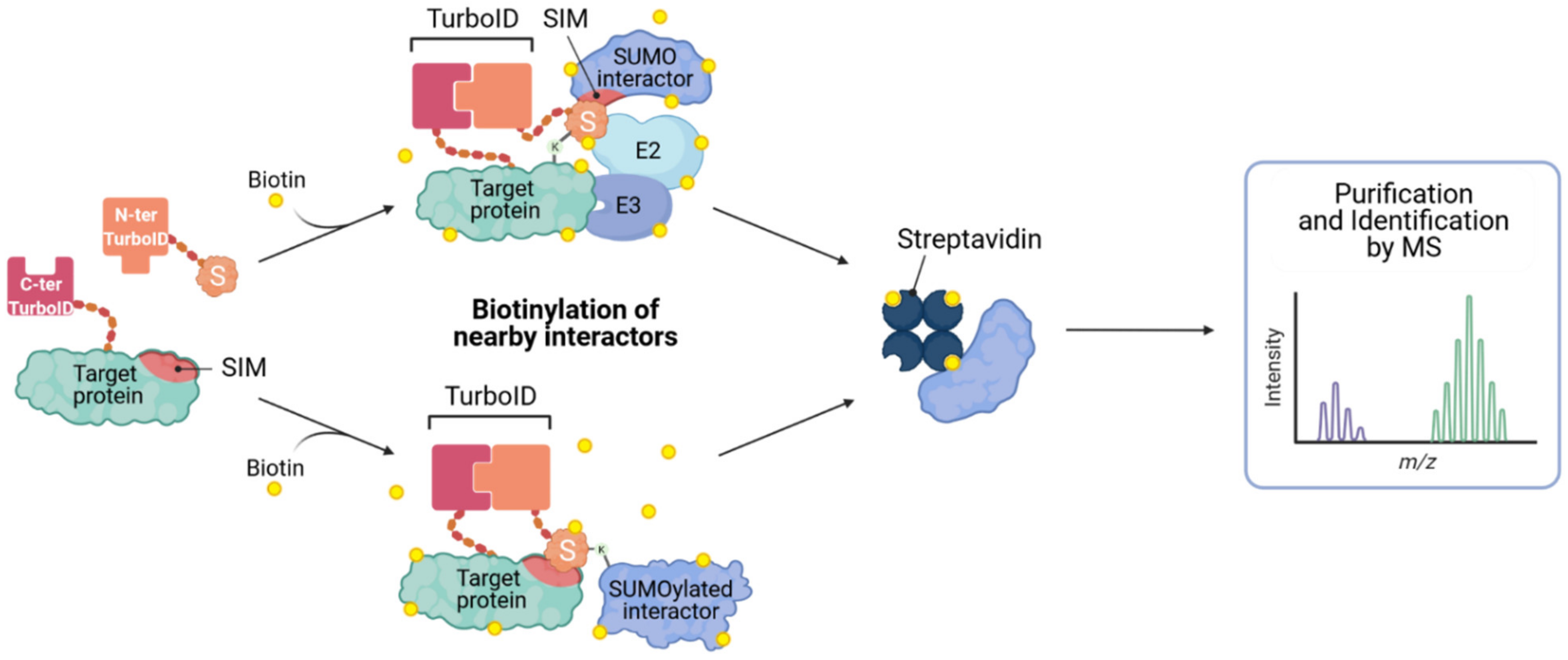

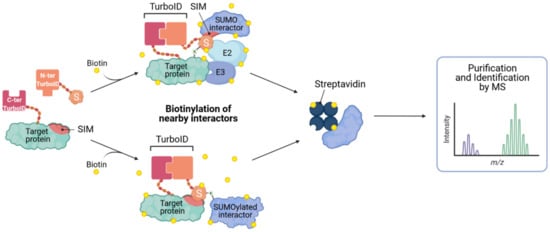

While most of the efforts described above focus on the identification of SUMO substrates and specific SUMOylation sites, it is clear that SUMO-dependent interactions are incredibly important in functionally ‘interpreting’ the changes in SUMOylation status of target proteins, either by affecting their cellular redistribution, complex formation, and/or stability. Thus, being able to identify SUMO-dependent interactions should also be a future goal of studies to better understand SUMOylation in the context of innate antiviral responses. As such, Barroso-Gomila et al. have developed a novel technology to identify SUMO-dependent interactors, termed SUMO-ID [68]. They devised a SUMO-centric approach that combines biotin proximity labeling by TurboID [69] with protein-fragment complementation (Split-TurboID), such that biotinylation is dependent on the proximity of the two fusion partners: one fragment of the Split-TurboID is fused to SUMO, and the other to a putative SUMOylated target (Figure 5). Target SUMOylation (or SUMO-SIM interaction) brings both fragments together, resulting in reconstitution of the TurboID enzyme, and allowing specific biotinylation of interactors, and other proximal proteins, in a SUMO-dependent manner. Biotin labeled proteins can then be enriched by streptavidin purification and identified by MS. This new method could prove to be a powerful tool for the identification of specific SUMO-dependent interactors of certain target proteins, and has the potential to allow functional discovery of SUMO enzymatic machinery or other ‘interpreters’ of SUMO modification.

Figure 5.

Identification of SUMO-interacting proteins by SUMO-ID. The N-terminal Split-TurboID construct is fused to the SUMO of interest, and the C-terminal fragment is fused to a potentially SUMOylated (or SIM-containing) target. Target SUMOylation, or SUMO-SIM interaction, results in reconstitution of the Split-TurboID and permits biotin labeling of proximal proteins. Biotinylated proteins can then be purified on streptavidin matrices and analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS). Concept developed in [68].

In summary, several different methodologies have been developed over the years to identify SUMO-modified proteins and to map specific sites of SUMOylation. These techniques can be, and have been, applied in unbiased, system-wide approaches to understand how the SUMOylation status of proteins changes with certain stress conditions, and thus all of these technologies could similarly be applied to understand how host cells respond to infection. There is clearly an experimental balance to be made between strategies that permit robust and efficient purification of SUMO targets, the reliable determination of SUMOylation sites (which so far relies on ectopic expression of tagged, and sometimes mutant, constructs) and the unavoidable potential for ensuing artefacts. These problems may be overcome if the field adopts genome-editing strategies to tag endogenous genes, or uses purification methods (which are currently lower yield) that can enrich fully endogenous SUMOylated material.

5. Concluding Remarks

Recent advances in MS-based technologies have facilitated the analysis of global changes in posttranslational modifications. Several novel methods have been established that enable the identification of site-specific SUMOylation, leading to the identification of thousands of SUMO targets. However, each of these technologies has certain advantages and disadvantages, with one major caveat being the dependence on ectopic expression of epitope-tagged SUMO and SUMO mutants. Overexpression might also overwhelm specificity in the SUMO machinery, resulting in SUMOylation of unnatural SUMO targets, unexpected artefacts, and detrimental changes in signal transduction. Therefore future research should focus on the establishment of physiologically relevant approaches, such as endogenous tagging of SUMO paralogs. For example, knock-in of His6-HA-tagged SUMO1 in mice seems to be well tolerated, and such mice showed no overt phenotypic abnormalities, yet might prove to be a useful tool [50]. In addition to identification of SUMO targets, characterization of the SUMO interactome will of course be of considerable interest, and a novel technique (SUMO-ID) was recently developed to tackle this challenge [68].

SUMOylation has been shown to be involved in many aspects of virus infection and innate immune responses, having both positive and negative effects. Current research interests have been dedicated to the dissection of global SUMOylation changes and determination of SUMO targets in the context of infection and IFN responses. A number of studies have therefore employed SUMO proteomics leading to the discovery of novel concepts in innate immunity [33,34,35,36,37]. However, many factors that had been previously described in small-scale studies were not detected with these methods. This might be owing to the experimental setup (nature of the stimulus, time points, cell lines, SUMO proteomics strategy), as, for example, there were no studies yet analyzing global SUMOylation after short times of infection or direct stimulation with TLR/RLR agonists that might be necessary to identify viral sensors or downstream signaling components as SUMO targets. Nevertheless, the datasets generated in these studies are undoubtedly opening avenues for further research.

Though a great deal of research has been devoted to SUMOylation and infection, many challenges and open questions remain. With the identification of SUMO substrates, SUMOylation sites, and the SUMO interactome, the challenge remains how to analyze the specific consequences of SUMOylation on its targets and in the wider context of the pathogen being studied. It further remains unclear how global changes in SUMOylation are triggered in the context of innate immune responses (e.g., cellular stress or direct induction by viral proteins). Delineating the molecular mechanisms of SUMO pathways might therefore open up novel opportunities for therapeutic interventions. For example, viruses that depend on SUMO-related mechanisms for replication could be inhibited by specific targeting of required SUMO-related host proteins. The observation that absence of SUMO2/3 results in a spontaneous IFN signature also suggests that the SUMOylation machinery might be a relevant target for autoimmune or auto-inflammatory therapeutics.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, M.L., G.L. and B.G.H.; visualization, G.L.; supervision, B.G.H.; project administration, B.G.H.; funding acquisition, B.G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Work in the authors’ laboratory is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation through grant number 31003A_182464.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Matunis, M.J.; Coutavas, E.; Blobel, G. A novel ubiquitin-like modification modulates the partitioning of the Ran-GTPase-activating protein RanGAP1 between the cytosol and the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 135, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flotho, A.; Melchior, F. Sumoylation: A regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohideen, F.; Lima, C.D. SUMO takes control of a ubiquitin-specific protease. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chu, Y.; Yang, X. SUMO E3 ligase activity of TRIM proteins. Oncogene 2011, 30, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichler, A.; Gast, A.; Seeler, J.S.; Dejean, A.; Melchior, F. The nucleoporin RanBP2 Has SUMO1 E3 ligase activity. Cell 2002, 108, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Muller, S. Members of the PIAS family act as SUMO ligases for c-Jun and p53 and repress p53 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 2872–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gareau, J.R.; Lima, C.D. The SUMO pathway: Emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, C.M.; Wilson, N.R.; Hochstrasser, M. Function and regulation of SUMO proteases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Au, S.W.N. Mapping residues of SUMO precursors essential in differential maturation by SUMO-specific protease, SENP1. Biochem. J. 2005, 386, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois, L.M.; Lima, C.D. Structures of the SUMO E1 provide mechanistic insights into SUMO activation and E2 recruitment to E1. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matic, I.; Schimmel, J.; Hendriks, I.A.; van Santen, M.A.; van de Rijke, F.; van Dam, H.; Gnad, F.; Mann, M.; Vertegaal, A.C.O. Site-specific identification of SUMO-2 targets in cells reveals an inverted SUMOylation motif and a hydrophobic cluster SUMOylation motif. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozluoğlu, M.; Karaca, E.; Nussinov, R.; Haliloğlu, T. A mechanistic view of the role of E3 in Sumoylation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010, 6, e1000913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, N.; Chaugule, V.K.; Koidl, S.; Droescher, M.; Dogan, E.; Rettich, J.; Sutinen, P.; Imanishi, S.Y.; Hofmann, K.; Palvimo, J.J.; et al. A new vertebrate SUMO enzyme family reveals insights into SUMO-chain assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiss-Friedlander, R.; Melchior, F. Concepts in sumoylation: A decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriramachandran, A.M.; Dohmen, R.J. SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Müller, S. SUMO-specific proteases/isopeptidases: SENPs and beyond. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, K.; Piller, T.; Müller, S. SUMO-specific proteases and isopeptidases of the SENP family at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, R.D.; Boutell, C.; Hale, B.G. Interplay between viruses and host sumoylation pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazear, H.M.; Schoggins, J.W.; Diamond, M.S. Shared and distinct functions of type I and type III interferons. Immunity 2019, 50, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesev, E.V.; LeDesma, R.A.; Ploss, A. Decoding type I and III interferon signalling during viral infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, S.; Lee-Kirsch, M.A. Type I interferon-mediated autoinflammation and autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017, 49, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimoto, K.I.; Miyauchi, S.; Stoner, S.A.; Fan, J.B.; Zhang, D.E. Negative regulation of type I IFN signaling. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.M.; Liao, C.Y.; Yang, Q.; Xie, X.Q.; Shu, H.B. Innate immunity to RNA virus is regulated by temporal and reversible sumoylation of RIG-I and MDA5. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Yu, H.; Zheng, X.; Peng, R.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Qu, B.; Shen, N.; et al. SENP7 potentiates cGAS activation by relieving SUMO-mediated inhibition of Cytosolic DNA sensing. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.-M.; Yang, Q.; Xie, X.-Q.; Liao, C.-Y.; Lin, H.; Liu, T.-T.; Yin, L.; Shu, H.-B. Sumoylation promotes the stability of the DNA sensor cGAS and the adaptor STING to regulate the kinetics of response to DNA virus. Immunity 2016, 45, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, G.W.; Lee, Y.; Yun, M.; Kang, J.; Lee, S.B. Formation of SUMO3-conjugated chains of MAVS induced by poly(dA:dT), a ligand of RIG-I, enhances the aggregation of MAVS that drives the secretion of interferon-β in human keratinocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 522, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Chang, T.H.; Tailor, P.; Sasaki, T.; Tashiro, M.; Kato, A.; Ozato, K. Virus infection triggers SUMOylation of IRF3 and IRF7, leading to the negative regulation of type I interferon gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 25660–25670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maarifi, G.; Maroui, M.A.; Dutrieux, J.; Dianoux, L.; Nisole, S.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K. Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier Alters IFN Response. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 2312–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Asmi, F.; McManus, F.P.; Thibault, P.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K. Interferon, restriction factors and SUMO pathways. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 55, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desterro, J.M.P.; Keegan, L.P.; Jaffray, E.; Hay, R.T.; O’Connell, M.A.; Carmo-Fonseca, M. SUMO-1 modification alters ADAR1 editing activity. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 5115–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoun, Z.; Maarifi, G.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K. The implication of SUMO in intrinsic and innate immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016, 29, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, P.; Golebiowski, F.; Tatham, M.H.; Lopes, A.M.; Taggart, A.; Hay, R.T.; Hale, B.G. Global reprogramming of host SUMOylation during influenza virus infection. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 1467–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Asmi, F.; McManus, F.P.; Brantis-de-Carvalho, C.E.; Valle-Casuso, J.C.; Thibault, P.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K. Cross-talk between SUMOylation and ISGylation in response to interferon. Cytokine 2020, 129, 155025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroui, M.A.; Maarifi, G.; McManus, F.P.; Lamoliatte, F.; Thibault, P.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K. Promyelocytic Leukemia protein (PML) requirement for interferon-induced global cellular SUMOylation. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2018, 17, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

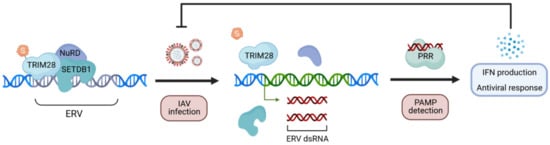

- Schmidt, N.; Domingues, P.; Golebiowski, F.; Patzina, C.; Tatham, M.H.; Hay, R.T.; Hale, B.G. An influenza virus-triggered SUMO switch orchestrates co-opted endogenous retroviruses to stimulate host antiviral immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 17399–17408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, E.; Tatham, M.H.; Groslambert, M.; Glass, M.; Orr, A.; Hay, R.T.; Everett, R.D. Analysis of the SUMO2 proteome during HSV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, I.A.; Vertegaal, A.C.O. A comprehensive compilation of SUMO proteomics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decque, A.; Joffre, O.; Magalhaes, J.G.; Cossec, J.C.; Blecher-Gonen, R.; Lapaquette, P.; Silvin, A.; Manel, N.; Joubert, P.E.; Seeler, J.S.; et al. Sumoylation coordinates the repression of inflammatory and anti-viral gene-expression programs during innate sensing. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowl, J.T.; Stetson, D.B. SUMO2 and SUMO3 redundantly prevent a noncanonical type I interferon response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6798–6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.-J.; Park, J.-S.; Um, S.-J. Ubc9-mediated sumoylation leads to transcriptional repression of IRF-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 377, 952–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witze, E.S.; Old, W.M.; Resing, K.A.; Ahn, N.G. Mapping protein post-translational modifications with mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 2007, 4, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, C.; Thomanek, N.; Hundt, F.; Lerari, T.; Meyer, H.E.; Wolters, D.; Marcus, K. Strategies in relative and absolute quantitative mass spectrometry based proteomics. Biol. Chem. 2017, 398, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Paige, J.S.; Jaffrey, S.R. Global analysis of lysine ubiquitination by ubiquitin remnant immunoaffinity profiling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.T. SUMO: A history of modification. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, D.; Dasso, M. Modification in reverse: The SUMO proteases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007, 32, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golebiowski, F.; Matic, I.; Tatham, M.H.; Cole, C.; Yin, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Cox, J.; Barton, G.J.; Mann, M.; Hay, R.T. System-wide changes to SUMO modifications in response to heat shock. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmel, J.; Eifler, K.; Sigurðsson, J.O.; Cuijpers, S.A.; Hendriks, I.A.; Verlaan-de Vries, M.; Kelstrup, C.D.; Francavilla, C.; Medema, R.H.; Olsen, J.V.; et al. Uncovering SUMOylation dynamics during cell-cycle progression reveals FoxM1 as a key mitotic SUMO target protein. Mol. Cell 2014, 53, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatham, M.H.; Matic, I.; Mann, M.; Hay, R.T. Comparative proteomic analysis identifies a role for SUMO in protein quality control. Sci. Signal. 2011, 4, rs4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirard, M.; Hsiao, H.H.; Nikolov, M.; Urlaub, H.; Melchior, F.; Brose, N. In vivo localization and identification of SUMOylated proteins in the brain of His6-HA-SUMO1 knock-in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21122–21127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertegaal, A.C.; Andersen, J.S.; Ogg, S.C.; Hay, R.T.; Mann, M.; Lamond, A.I. Distinct and overlapping sets of SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 target proteins revealed by quantitative proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2006, 5, 2298–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertegaal, A.C.; Ogg, S.C.; Jaffray, E.; Rodriguez, M.S.; Hay, R.T.; Andersen, J.S.; Mann, M.; Lamond, A.I. A proteomic study of SUMO-2 target proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 33791–33798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, D.H.; Carré, A.; Guzzardo, P.M.; Banning, C.; Mangena, R.; Henley, T.; Oberndorfer, S.; Gapp, B.V.; Nijman, S.M.B.; Brummelkamp, T.R.; et al. A generic strategy for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene tagging. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impens, F.; Radoshevich, L.; Cossart, P.; Ribet, D. Mapping of SUMO sites and analysis of SUMOylation changes induced by external stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12432–12437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammsalu, T.; Matic, I.; Jaffray, E.G.; Ibrahim, A.F.M.; Tatham, M.H.; Hay, R.T. Proteome-wide identification of SUMO2 modification sites. Sci. Signal. 2014, 7, rs2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatham, M.H.; Jaffray, E.; Vaughan, O.A.; Desterro, J.M.P.; Botting, C.H.; Naismith, J.H.; Hay, R.T. Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 35368–35374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmel, J.; Larsen, K.M.; Matic, I.; van Hagen, M.; Cox, J.; Mann, M.; Andersen, J.S.; Vertegaal, A.C.O. The ubiquitin-proteasome system is a key component of the SUMO-2/3 cycle. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2008, 7, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, I.A.; Vertegaal, A.C. A high-yield double-purification proteomics strategy for the identification of SUMO sites. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1630–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galisson, F.; Mahrouche, L.; Courcelles, M.; Bonneil, E.; Meloche, S.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K.; Thibault, P. A novel proteomics approach to identify SUMOylated proteins and their modification sites in human cells. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2011, 10, M110.004796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoliatte, F.; Caron, D.; Durette, C.; Mahrouche, L.; Maroui, M.A.; Caron-Lizotte, O.; Bonneil, E.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K.; Thibault, P. Large-scale analysis of lysine SUMOylation by SUMO remnant immunoaffinity profiling. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerpe, R.; Aillet, F.; Lopitz-Otsoa, F.; Lang, V.; England, P.; Rodriguez, M.S. Efficient protection and isolation of ubiquitylated proteins using tandem ubiquitin-binding entities. EMBO Rep. 2009, 10, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruderer, R.; Tatham, M.H.; Plechanovova, A.; Matic, I.; Garg, A.K.; Hay, R.T. Purification and identification of endogenous polySUMO conjugates. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva-Ferrada, E.; Xolalpa, W.; Lang, V.; Aillet, F.; Martin-Ruiz, I.; de la Cruz-Herrera, C.F.; Lopitz-Otsoa, F.; Carracedo, A.; Goldenberg, S.J.; Rivas, C.; et al. Analysis of SUMOylated proteins using SUMO-traps. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, V.; Da Silva-Ferrada, E.; Barrio, R.; Sutherland, J.D.; Rodriguez, M.S. Using Biotinylated SUMO-Traps to Analyze SUMOylated Proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1475, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Barysch, S.V.; Karaca, S.; Dittner, C.; Hsiao, H.H.; Berriel Diaz, M.; Herzig, S.; Urlaub, H.; Melchior, F. Detecting endogenous SUMO targets in mammalian cells and tissues. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, I.A.; Lyon, D.; Su, D.; Skotte, N.H.; Daniel, J.A.; Jensen, L.J.; Nielsen, M.L. Site-specific characterization of endogenous SUMOylation across species and organs. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumpkin, R.J.; Gu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Leonard, M.; Ahmad, A.S.; Clauser, K.R.; Meyer, J.G.; Bennett, E.J.; Komives, E.A. Site-specific identification and quantitation of endogenous SUMO modifications under native conditions. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Gomila, O.; Trulsson, F.; Muratore, V.; Canosa, I.; Cortazar, A.R.; Perez, C.; Azkargorta, M.; Iloro, I.; Carracedo, A.; Aransay, A.M.; et al. Identification of proximal SUMO-dependent interactors using SUMO-ID. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branon, T.C.; Bosch, J.A.; Sanchez, A.D.; Udeshi, N.D.; Svinkina, T.; Carr, S.A.; Feldman, J.L.; Perrimon, N.; Ting, A.Y. Efficient proximity labeling in living cells and organisms with TurboID. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Ferhi, O.; Carnec, X.; Zamborlini, A.; Peres, L.; Jollivet, F.; Vitaliano-Prunier, A.; de Thé, H.; Lallemand-Breitenbach, V. Interferon controls SUMO availability via the Lin28 and let-7 axis to impede virus replication. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, J.; Yang, N.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; et al. FAT10 Is critical in influenza a virus replication by inhibiting Type I IFN. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutell, C.; Everett, R.D. Regulation of alphaherpesvirus infections by the ICP0 family of proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuchet-Lourenço, D.; Boutell, C.; Lukashchuk, V.; Grant, K.; Sykes, A.; Murray, J.; Orr, A.; Everett, R.D. SUMO pathway dependent recruitment of cellular repressors to herpes simplex virus type 1 genomes. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.C.; Dybas, J.M.; Hughes, J.; Weitzman, M.D.; Boutell, C. The HSV-1 ubiquitin ligase ICP0: Modifying the cellular proteome to promote infection. Virus Res. 2020, 285, 198015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, E.; Orr, A.; Everett, R.D. MORC3, a Component of PML nuclear bodies, has a role in restricting Herpes Simplex virus 1 and human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8621–8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Santos, A.; Rosas, J.M.; Ortiz-Guzman, J.; Rosas-Acosta, G. Influenza A virus interacts extensively with the cellular SUMOylation system during infection. Virus Res. 2011, 158, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, P.; Eletto, D.; Magnus, C.; Turkington, H.L.; Schmutz, S.; Zagordi, O.; Lenk, M.; Beer, M.; Stertz, S.; Hale, B.G. Profiling host ANP32A splicing landscapes to predict influenza A virus polymerase adaptation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Giotis, E.S.; Moncorgé, O.; Frise, R.; Mistry, B.; James, J.; Morisson, M.; Iqbal, M.; Vignal, A.; Skinner, M.A.; et al. Species difference in ANP32A underlies influenza A virus polymerase host restriction. Nature 2016, 529, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staller, E.; Sheppard, C.M.; Neasham, P.J.; Mistry, B.; Peacock, T.P.; Goldhill, D.H.; Long, J.S.; Barclay, W.S. ANP32 proteins are essential for influenza virus replication in human cells. J. Virol. 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, P.; Hale, B.G. Functional Insights into ANP32A-dependent influenza a virus polymerase host restriction. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 2538–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazzi, I.; Ho, J.S.; Kim, J.; Manicassamy, B.; Dewell, S.; Albrecht, R.A.; Seibert, C.W.; Schaefer, U.; Jeffrey, K.L.; Prinjha, R.K.; et al. Suppression of the antiviral response by an influenza histone mimic. Nature 2012, 483, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenschow, D.J.; Lai, C.; Frias-Staheli, N.; Giannakopoulos, N.V.; Lutz, A.; Wolff, T.; Osiak, A.; Levine, B.; Schmidt, R.E.; García-Sastre, A.; et al. IFN-stimulated gene 15 functions as a critical antiviral molecule against influenza, herpes, and Sindbis viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Peng, H.; Yurchenko, V.; Yap, K.L.; Negorev, D.G.; Schultz, D.C.; Psulkowski, E.; Fredericks, W.J.; White, D.E.; Maul, G.G.; et al. PHD domain-mediated E3 ligase activity directs intramolecular sumoylation of an adjacent bromodomain required for gene silencing. Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascle, X.H.; Germain-Desprez, D.; Huynh, P.; Estephan, P.; Aubry, M. Sumoylation of the transcriptional intermediary factor 1beta (TIF1beta), the Co-repressor of the KRAB Multifinger proteins, is required for its transcriptional activity and is modulated by the KRAB domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 10190–10202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Leung, D.; Miyashita, H.; Maksakova, I.A.; Miyachi, H.; Kimura, H.; Tachibana, M.; Lorincz, M.C.; Shinkai, Y. Proviral silencing in embryonic stem cells requires the histone methyltransferase ESET. Nature 2010, 464, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, H.M.; Jakobsson, J.; Mesnard, D.; Rougemont, J.; Reynard, S.; Aktas, T.; Maillard, P.V.; Layard-Liesching, H.; Verp, S.; Marquis, J.; et al. KAP1 controls endogenous retroviruses in embryonic stem cells. Nature 2010, 463, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turelli, P.; Castro-Diaz, N.; Marzetta, F.; Kapopoulou, A.; Raclot, C.; Duc, J.; Tieng, V.; Quenneville, S.; Trono, D. Interplay of TRIM28 and DNA methylation in controlling human endogenous retroelements. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappinelli, K.B.; Strissel, P.L.; Desrichard, A.; Li, H.; Henke, C.; Akman, B.; Hein, A.; Rote, N.S.; Cope, L.M.; Snyder, A.; et al. Inhibiting DNA methylation causes an interferon response in cancer via dsRNA including endogenous retroviruses. Cell 2015, 162, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulois, D.; Loo Yau, H.; Singhania, R.; Wang, Y.; Danesh, A.; Shen, S.Y.; Han, H.; Liang, G.; Jones, P.A.; Pugh, T.J.; et al. DNA-demethylating agents target colorectal cancer cells by inducing viral mimicry by endogenous transcripts. Cell 2015, 162, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, C.H.; Fernandes, L.; Conde, L.; Robbez-Masson, L.; Sumner, R.P.; Peacock, T.; Rodriguez-Plata, M.T.; Mickute, G.; Gifford, R.; Towers, G.J.; et al. KAP1 regulates endogenous retroviruses in adult human cells and contributes to innate immune control. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).