Abstract

Blockchain technology is a sustainable technology that offers a high level of security for many industrial applications. Blockchain has numerous benefits, such as decentralisation, immutability and tamper-proofing. Blockchain is composed of two processes, namely, mining (the process of adding a new block or transaction to the global public ledger created by the previous block) and validation (the process of validating the new block added). Several consensus protocols have been introduced to validate blockchain transactions, Proof-of-Work (PoW) and Proof-of-Stake (PoS), which are crucial to cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin. However, these consensus protocols are vulnerable to double-spending attacks. Amongst these attacks, the 51% attack is the most prominent because it involves forking a blockchain to conduct double spending. Many attempts have been made to solve this issue, and examples include delayed proof-of-work (PoW) and several Byzantine fault tolerance mechanisms. These attempts, however, suffer from delay issues and unsorted block sequences. This study proposes a hybrid algorithm that combines PoS and PoW mechanisms to provide a fair mining reward to the miner/validator by conducting forking to combine PoW and PoS consensuses. As demonstrated by the experimental results, the proposed algorithm can reduce the possibility of intruders performing double mining because it requires achieving 100% dominance in the network, which is impossible.

1. Introduction

Blockchain technology has been widely used in various distributed system contexts, including content distribution networks [1], smart grid systems [2], e-healthcare [3], real estate [4,5], e-finance [6], e-education [7], supply chains, e-voting, smart homes [8,9], smart cities [10] and smart industries [11,12]. The advent of blockchain technology has affected the global financial system through digital currencies. In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto invented a revolutionary electronic cash system called Bitcoin (a digital currency) that made peer-to-peer electronic transactions possible. This peer-to-peer digital currency system was designed to eliminate the need for third parties in financial transactions between unknown parties in a trustworthy and verifiable way [13]. In January 2009, the same group created software as an open-source code and introduced the first digital currency in history [14]. As the fundamental technology of Bitcoin, blockchain consists of a transparent and immutable list of chained blocks of transactions. In the peer-to-peer network, each peer maintains a copy of the blockchain known as the distributed ledger.

Blockchain acts as a decentralised public ledger for recording data as blocks, which constitute a connected list data structure used to indicate logical relationships between the data added to the blockchain. The data blocks can be retained without the involvement of a centralised agency or intermediary. In another alternative, data blocks are copied and exchanged throughout the entire blockchain network, thereby eliminating device failure, data management and cyber-attacks. The two most important processes of blockchain are block mining and block validation. The mining process involves adding a new block or transaction to the public global ledger. The new block or transaction is then validated in a process known as block validation. To understand how blockchain operates, we need to understand its four underlying layers. At the lowest layer are peers sign transactions, which represent an agreement between two parties, such as exchanging physical or digital property or completing a task. To ensure the absence of corrupt branches and divergences [15], the nodes must agree on which transactions should be kept in the blockchain, which is the responsibility of the consensus layer. The third layer is the compute interface. Through the compute interface, the blockchain is able to provide increased functionality. Blockchain maintains a record of each transaction undertaken by a user so that by calculating the balance of each user, the overall balance may be determined. The last layer, governance, extends the blockchain architecture to human interaction in the physical realm. Therefore, the popularity of blockchain is inevitable because the technology can provide desirable features by replacing the centralised communication architectures of today. The core protocol of blockchain, particularly in blockchain-based cryptocurrencies, refers to the consensus protocol. The consensus protocol enables all peers to agree on every block inclusion in the distributed ledger [16]. As a result of a consensus mechanism, all truthful nodes establish mutual agreement on a consistent ledger in asynchronous, untrusted networks [17]. The consensus protocols are well-defined, but inputs from various stakeholders are also considered, which affects the blockchain’s authenticity. Incorporating new methods for improving consensus protocols and/or patching systems is therefore essential to the development of blockchains.

Different consensus mechanisms are required to ensure the security of digital transactions due to the varying types of blockchain technology [18]. A common consensus mechanism is proof-of-work (PoW), in which the parties must demonstrate their rights to add a node by solving an increasingly complicated computational problem to ensure authentication and compliance, including identifying thresholds for harm, such as leading zeros [19]. Given that the PoW protocol needs tremendous computing power to solve the block complexity in Bitcoin [20], another consensus protocol called proof-of-stack (PoS) was proposed to overcome the problems of the PoW protocol. Despite the high complexity of the PoS consensus, this protocol may be vulnerable to stack problems if more than half of the network is manipulated to prevent a new block from being distributed to confirm transactions [21]. A PoS protocol separates stake blocks according to the relative hashing rates of miners (i.e., their computational power) in relation to the resource capacity of existing miners [22]. This approach makes the choice fair and prevents the richest participant from dominating the network. Many blockchains, such as Ethereum [23], opt for PoS because power consumption and scalability are greatly reduced. Several consensus approaches, including Byzantine fault tolerance (BFT) and its variants, are also available [24].

However, despite the application of consensus protocols, which prevent many security breaches, several malicious attacks have occasionally hampered the growth of blockchain technology. For example, certain attacks, such as Eclipse, Sybil, BGP deterrence, and 51%, are triggered as a result of attempts to penetrate the blockchain network. Amongst these attacks, the 51% attack has received the least attention from researchers due to its high costs. However, recent security incidents have demonstrated that 51% attacks can be carried out against various contemporary cryptocurrencies [25]. Compared with other consensus protocols, PoW immediately challenges 51% attacks, where recent attacks have mainly focused on PoW-dependent cryptocurrencies [26]. This is one of the most severe dangers associated with a PoW-based cryptocurrency because it assumes that if a fraudulent peer network is allowed to obtain more than 50% of the network assets (i.e., computing power), its members become the majority of the network’s decision makers. Peers with superior processing skills could dominate the network because they have the capability to mine numerous blocks as peers compete for fast access. They can easily exploit the blockchain by creating fake transactions, and the fraud perpetrated by other users may result in large-scale financial losses.

To prevent this attack, researchers have performed various studies. The majority of them recommended combining two or more resource proofs into a hybrid protocol to combat this attack [27,28,29,30,31]. However, mixing two or more existing protocols (hybrid protocol) makes the network resistant to this attack. Therefore, the recent implementation of hybrid protocols has other challenges and drawbacks that need to be addressed. For example, several have added voting systems, ticket delivery systems, fines, special nodes and block validator groups to deter malicious behaviour [32]. These measures are successful in protecting the network against 51% attacks. However, their primary weakness is in rewarding block mining to investors, which pertains to the number of Bitcoins you receive if you are successful in mining a block. Undoubtedly, the investor invests his hard-earned money in a cryptocurrency to reap the benefits of his investment. These benefits may be derived from the block mining reward. In this scenario, the accuracy of the block generation time interval is crucial in ensuring that this benefit is delivered to the appropriate consumer at the appropriate time. However, the voting, ticket and other systems are not time-controlled, and no consistent distribution of benefits occurs over the block reward generation intervals. Another major issue is the diversification of peers by establishing special committees and validation groups that violate the P2P network’s principle.

Hence, this study proposes a hybrid consensus protocol that integrates PoW and PoS to control block generation time in two ways. Firstly, our proposed model uses the PoW mining method for the first time to prevent the block generation time from exceeding a specified threshold. Secondly, the generated block is validated by the PoS consensus without any need for voting or commission approval. In the proposed model, each block is validated by the entire network. Hybridisation is one of the aspects that make our study unique and novel compared with previous studies. In addition to being able to handle the 51% attack, the framework ensures a standardised distribution of mining rewards to stakeholders and investors by maintaining a precise block generation interval with difficulty adjustment in PoW mining and stakeholder probability calculation based on their mature stake balance. This study proposes a hybrid algorithm that combines the PoW and PoS mechanisms to ensure a fair mining reward between the miner and validator by controlling the block generation time. To ensure long-term sustainability, the proposed model entails a complexity analysis. The important contributions of this work can be summarised as follows:

- We evaluated three security protection measures that are specific to the 51% attack and demonstrated their vulnerabilities to exploitation by the 51% attack.

- We proposed a model to control the block generation time with the distributed validation technique, which enhances blockchain security and performance.

- We hybridised PoW and PoS consensuses to solve the above-mentioned issue for the fair mining and stacking mechanism, which by default prevents the 51% attack.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a background of the topic and related work wherein blockchain and previous attempts are described and investigated. Section 3 provides an overview of the methodology adopted in this study and a description of the experiment’s algorithms. The analysis and results are given in Section 4, and the conclusions and future work directions are presented in Section 5.

2. Background and Related Work

In the past few years, blockchain technology has been applied to cryptocurrencies. In the blockchain concept, data are exchanged from peer to peer in a distributed and decentralised manner [33]. In principle, all blockchain technologies employ the concept of a distributed ledger, in which the data are stored on a decentralised mechanism, with a cryptographic key being distributed across the network to ensure that each transaction matches its corresponding entity [34]. Data should be checked and validated before entering the ledger, which is why a consensus protocol is required. Although the scalability trilemma affects the development of blockchain technologies, this trilemma has no formal definition in the literature, but it has been reported in numerous studies, such as in [35,36]. Its definition was coined by Vitalik Buterin, the developer of Ethereum, a blockchain based on PoW that specifies the three characteristics a blockchain must possess if it is to expand globally: decentralisation, security and scalability. As shown in Figure 1, the scalability trilemma is symbolised by a triangle whose vertices represent three properties. The blockchain with optimal scalability is at the centre of the figure, which is not currently applicable. Brief descriptions of the three properties are presented below.

Figure 1.

Representation of the blockchain scalability trilemma; according to the trilemma, a blockchain can be on one side of the triangle and not in the center, which represents the best.

2.1. Decentralisation

Decentralisation ensures that transactions are verified and confirmed by a community of nodes and not by a central authority or a select committee, as in conventional systems. In other words, decisions are made by a distributed consensus, so any transaction does not require the trust of a third party. Consequently, the decisions made by network members are democratic, and any changes made to the protocol will be approved if more than 50% of the participants agree. An example is the fork in Bitcoin Cash that occurred on 1 August 2017 [37], where the maximum size of a block was increased to 8 MB to allow more transactions to be accepted. Given that multiple nodes verify the decision, decentralisation leads to higher-quality decisions than centralised authorities. The trade-off is the speed of confirmation; if a transaction requires the confirmation of multiple participants, the speed is less than that of a decision made by a central authority [38].

2.2. Scalability

Global adoption is enabled by the property of scalability, which refers to a system’s capability to adjust to increased loads. Bitcoin and Ethereum, two of the most widely used blockchain technologies, can process a maximum of seven and twelve transactions per second (TPS) unlike Visa, which can process 65,000 TPS [39]. Moreover, EOS [40], which is designed to be scalable, claims a throughput of around 2000 TPS but promises to be able to process millions of transactions in the future at the price of decentralisation.

2.3. Security

Security is a fundamental requirement in a blockchain. Insufficient or absent security permits an attacker to spend the same amount several times (double spending), thereby enriching himself at the expense of others and changing the blockchain’s immutable status. Such a scenario could occur in a 51% attack. Notably, the blockchain scalability trilemma is not a theorem, but in the context of distributed systems, the combination of consistency, availability and partition tolerance (CAP) is a fundamental theorem. This combination emphasises the difficulty of creating a decentralised, secure, scalable system, particularly in the case of blockchain technology, which is still developing and immature. The Bitcoin Blockchain, for example, features high security and decentralisation, but it is not scalable; the maximum number of transactions it can support is seven per second. Although it is not used as the sole currency, it represents a significant milestone in computer history by demonstrating the use of a digital cryptocurrency in a peer-to-peer network.

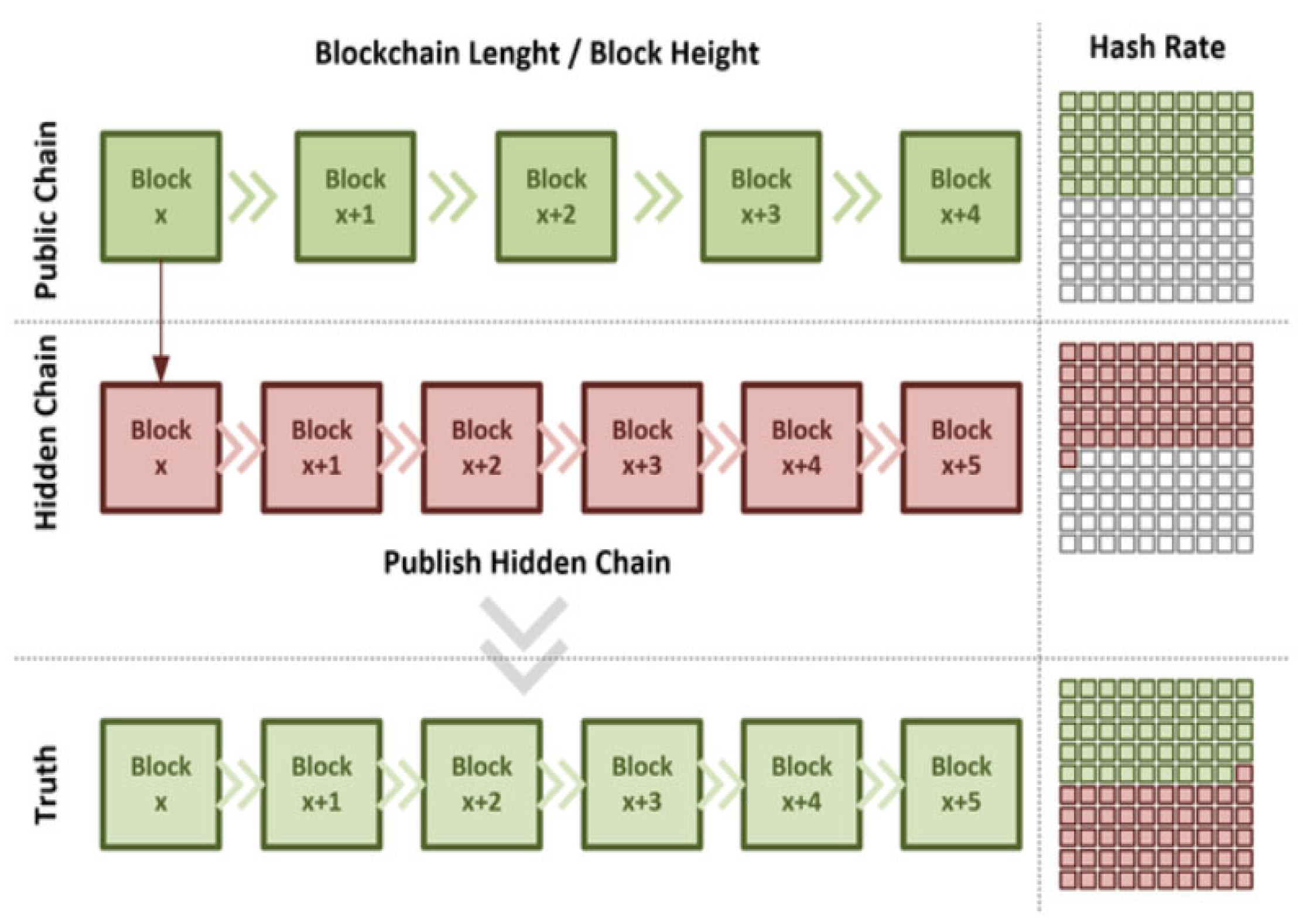

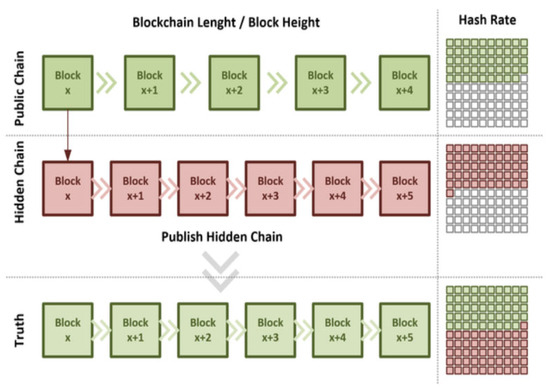

Additionally, most public blockchains, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum Classic [41], use a PoW consensus protocol to ensure that the data are immutable because all transactions must be mined to solve the complexity of the block. However, this protocol is susceptible to double-spending attacks, which occur when a user makes a second transaction with the same data as a previous one that has already been validated. Furthermore, if the miner controls more than 50% of the computing power managing the blockchain, he might be able to prevent the generation of a new block because any proposed change to the protocol must be supported by more than 50% of the participants. Therefore, amongst the numerous attacks that affect Blockchain protocols, 51% should receive additional attention. As a rule of thumb, blockchain technology is based on a distributed consensus mechanism that ensures mutual trust. When a miner owns more than 50% of the hash power in a PoW-based blockchain, he can carry out a 51% attack. In this case, he will receive 100% of the rewards from mining because he will create blockchains that are longer than those of any other miner. A double-spending attack can also occur if the same unspent transaction output (UTXO) is used for two transactions at the same time, thus erasing the last confirmed blocks from the blockchain and possibly corrupting the blockchain itself. Throughout the years, technologies such as Bitcoin that economically incentivise nodes to become miners have increased to a high number of nodes. Therefore, such an attack would require a considerable amount of hash power. Small blockchains, which have a hash power that is lower than that of Bitcoin, are not excluded from this attack. Examples of cryptocurrencies that are affected by 51% attacks include Monacoin [42], Bitcoin Gold [43] and ZenCash [44]. Furthermore, mining pools entail several miners sharing their computational power with several others who share the compensation proportionately to their shares of computing power. Owing to the advent of Bitcoin mining pools, an organisation can carry out a 51% attack if the sum of the hash power of all registered nodes exceeds 50% of the total network hash power. An example of Bitcoin blockchain 51% attack is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Illustration of Bitcoin blockchain 51% attack. If an attacker acquires more than half of the global hashing power, they will be able to mine a hidden chain that will eventually surpass the length of the public chain. Once the hidden chain surpasses the length of the public chain, it can be published and accepted as the new truth.

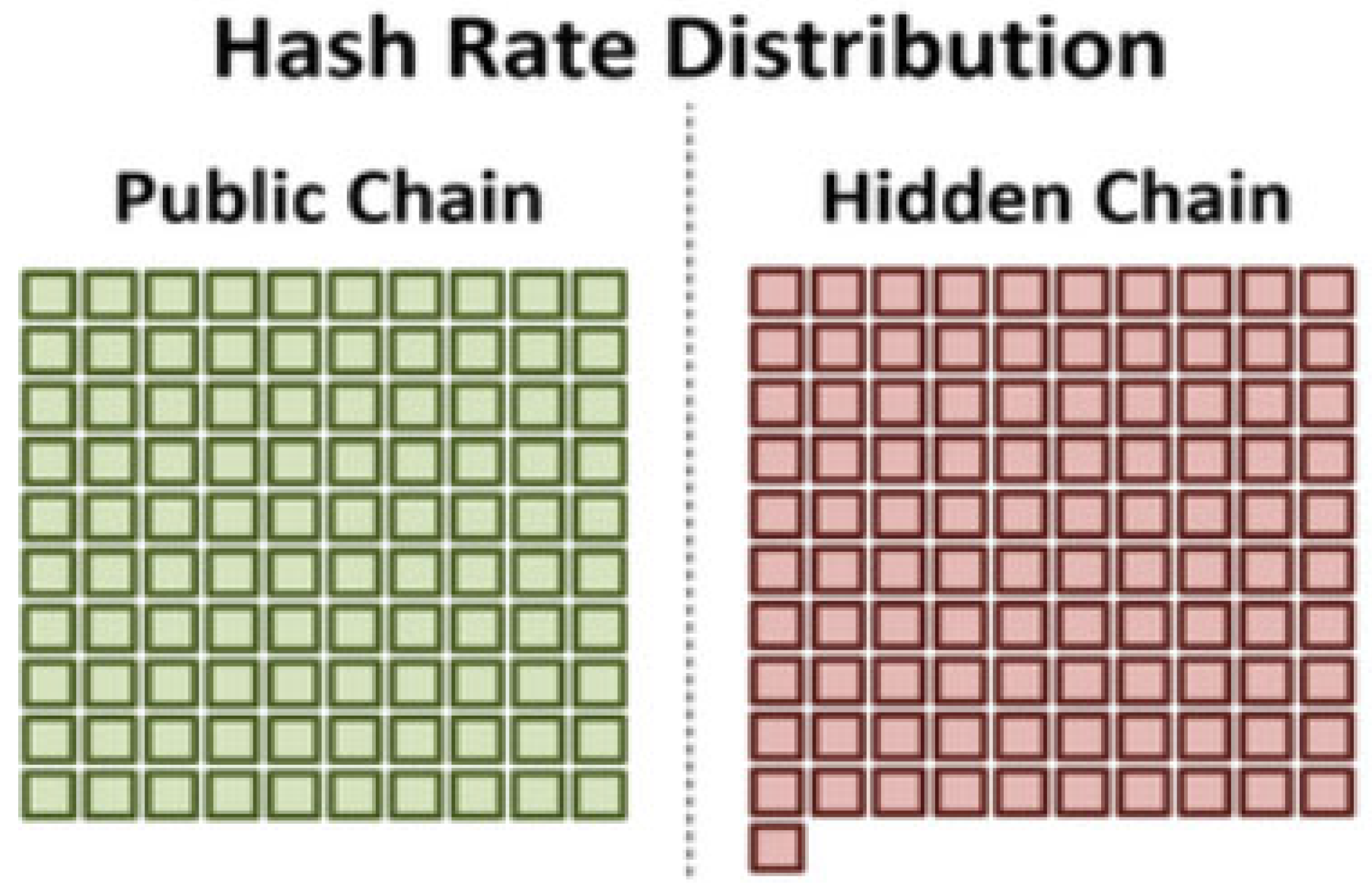

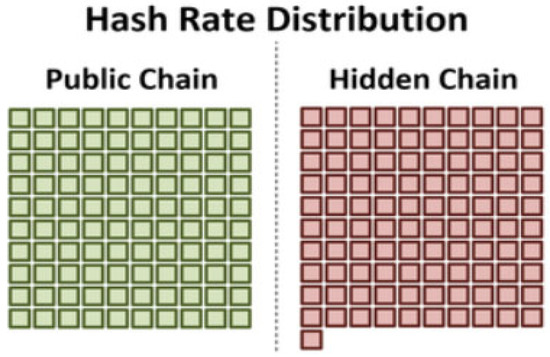

In addition, an attack with new hash power implies that an attacker has opted to obtain a more powerful hash power than that of the public chain, having the advantage of not knowing the start of the attack because no hashing power will leave the live network. Apart from the fact that this is a stealth attack, it does not force the difficulty to adjust to the live network as a result of a drop in its hash rate, thereby preventing new miners from joining the live network. In this case, the only factor that affects the live chain’s hash rate and complexity is the Bitcoin price itself. By contrast, this attack is twice as costly to execute as the current hash power attack. The execution of a 51% attack with new hash power is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Execution of a 51% attack with new hash power.

In sum, according to the literature, current systems have different aspects that make blockchains non-scalable [45]. Three critical aspects stand out in particular:

- New transactions are sent in broadcast to all the nodes of the network.

- All nodes receive each new block.

- A set of nodes is responsible for processing all the new transactions involved in the next block.

Given these aspects, the computational capacity and bandwidth of the individual nodes must be proportionally increased (vertical scalability). Horizontal scalability, in which additional nodes are added to the network in response to the increased volume of transactions, is preferable.

2.4. Consensus Mechanisms

In the blockchain network, the consensus mechanism is a set of rules designed to guarantee that all participants adhere to the same set of rules. The protocol ensures that each participant’s consent is used to carry out transactions to the distributed ledger [39]. A public blockchain is a decentralised technology, and no central authority is responsible for governing the necessary action. For this reason, the blockchain network requires the permission of network participants to verify and authenticate the activities taking place in the network. The entire process is executed by consensus amongst network members, which makes blockchain a trustworthy, secure, and efficient technology for digital transactions. Different consensus frameworks follow different standards that allow participants in the network to comply with these rules. To address the concerns of safe digital transactions, several consensus processes have been implemented. A few consensus protocols employed by major cryptocurrencies are PoW, PoS and delegated PoS (DPoS).

2.4.1. PoW

During mining, a new block is created by computing the block’s cryptographic hash. To prove its validity on the blockchain, a block hash must meet certain conditions. The Bitcoin blockchain, for example, starts each hash block with four trailing zeroes. Given that block data, which are transactional data, cannot be changed, the miner must modify the predefined hash pattern at every occurrence. The two network partners compete for the right nonce to create a valid block hash. Initially, the miner who seeks a solution attaches the block to the chain. As a reward for the miner’s efforts, the system produces a certain number of coins and provides the newly produced coins to the miner.

The PoW mechanism entirely relies on the computer power of the miner. The more computing power a miner has, the greater the chance of finding blocks and earning rewards [46]. In PoW consensus, half of the network’s nodes are assumed to remain trustworthy. As a result, this consensus is vulnerable because more than half the hashing power is owned by a single party. The cost of resources and hardware is one of the significant disadvantages of PoW. Several studies have reported that the energy consumption of Bitcoin mining is considerably higher than the energy consumption of 159 countries [47]. By contrast, the mining requirements and the mining time can differ depending on the algorithm used by each cryptocurrency. PoW mining is relatively slower than other consensus protocols. Given that a small number of mining pools dominate the Bitcoin network, attacks on these pools may result in severe disruptions. Recent attacks have demonstrated that PoW is vulnerable to 51% attacks. Low-hacking crypto coins based on PoW consensus are susceptible to 51% attacks because the requisite hash is easy to obtain. With the appropriate budget, the P+ epsilon attack can be conducted at no cost [48]. In addition, the researchers in [49] studied blockchain security and performance-based PoW. They presented a novel quantitative approach to examine the security and performance implications of various consensus and network parameters applied to PoW blockchains. Therefore, the approach proposed in [49] is solely based on PoW consensus, as opposed to hybrid mechanism approaches that offer higher levels of security and performance. Another study was conducted by [50] to review the role of blockchain in preventing future pandemics. Several applications of blockchain technology were also discussed, and these may assist in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.4.2. PoS

PoS is not dependent on a high computation capacity. It operates according to the staked properties of the network. In general, the more money a peer receives, the higher the incentive they will have to mine and reward. This mechanism does not require extremely high computational power. Little calculating power is required, so excessive electricity consumption is reduced [27]. Several limitations are associated with the PoS protocol. For example, large investors with enormous capital can manage the network to maximise their wealth, making the rich richer. PoS is also vulnerable to 51% attacks, especially when someone has more than 50% of the network wealth. An individual can exploit the blockchain easily for personal gain, resulting in malicious stakeholders gaining the majority of the supply by taking advantage of the nothing-at-stake issue. PoS suffers from low subjectivity and is thus challenging and demanding to implement [51]. To conduct a 51% attack, an opponent must obtain 51% of all cryptocurrencies. The cost of obtaining 51% of the overall stake is substantial. In light of this, the threat level posed by the 51% attack may be lower than that posed by PoW. According to our analysis, a long-range attack can exploit PoS. Carrying out the P + Epsilon attack is impossible because a large budget is required for an attacker to donate to the minority’s safety deposit. A Sybil attack can exploit PoS, and a DPoS attack can interrupt any portion of the network.

2.4.3. DPoS

DPoS is a consensus process that allows shareholders to vote on the nomination of witnesses [52]. In DPoS, the main objective is to minimise energy waste and accelerate transaction times. As a result of the overall block generation process, this consensus mechanism operates much more quickly than PoW consensus. In DPoS, each stakeholder is allowed to cast one vote per share; they can cast additional votes when they own additional coins. Moreover, the witnesses are rewarded for producing blocks and penalised for failing to do so, such that they are not paid and are voted out of office. To complete the instructed task, witnesses should receive the largest number of votes from random stakeholders. A stakeholder also votes on the restructuring of the delegates and adjusts the network, which will be reviewed by the stakeholder before a final decision. Although DPoS was designed to increase transaction efficiency and overcome the constraints imposed by many other consensus mechanisms, it has significant shortcomings. The network is not sufficiently decentralised due to a large number of validators. A centralised system may serve as a focal point for random intruders due to its centralised nature. DPoS is susceptible to 51% attacks because an attacker will convince stakeholders to give them 51% voting power in a 51% attack [40]. Asymmetric agreements are also vulnerable to other types of attacks, such as long-distance, DDoS, P + epsilon, Sybil and balanced attacks.

This work investigated the fact that the three main consensus systems, which are susceptible to several attacks, have significant weaknesses. As a result of their vulnerability, digital transactions are at a high risk of being attacked. Table 1 summarises the results of our analysis. The 51% attack can exploit all three consensus mechanisms, making it desirable for attackers, particularly for PoW where achieving the required hashing power is cost-effective.

Table 1.

Vulnerabilities of consensus mechanisms.

The following is a brief description of several severe attacks. However, the focus of this study is on 51% attacks. Long-range attacks are the result of a weak model of subjectivity [53]. This form of attack is similar to the 51% attack. It appears to fork the chain from the genesis block [54] rather than confirming the sixth block. This type of attack occurs very rarely in Bitcoin, but it can be damaging when demonstrating stakeholder consensus (PoS) and delegate stakeholder consensus (DPoS). Assuming a PoS consensus scenario in which the invaders begin with a limited number of coins shortly after the genesis block, their chain versions can be privately mined to carry out the attack. Given that they have a small stake, they will generate a limited number of blocks at the beginning and then generate a longer chain. PoS does not specify a threshold for chain lengthening, so the chains can become extremely long. The P + Epsilon attack is a method of exploiting the dominant strategies of the participants in the network. PoW-based blockchains are usually vulnerable to this type of attack [55]. When attackers give participants a pay-out in order to gain an advantage, a payoff matrix is used where the dominant tactic facilitates the achievement of the attacker’s objectives. As a result of the attack, the participants do not receive any compensation, and the attacker receives the entire amount. This key statistical finding is based on an ad hoc selection model.

2.5. Hybrid Approaches Related to 51% Attacks

The term 51% attacks refers to situations in which an attacker has 51% of the hashing power. As part of this attack, a private blockchain is created and completely disconnected from the actual chain edition. It is later introduced to the network as a real chain, which allows for a double-spending attack [47] Additionally, given that blockchain policy follows the most extended chain rule [56], if attackers gain 51% or more of the threat, they will push the longest chain by convincing network nodes to obey their chain. However, 51% of computational power is not strictly sufficient, so double spending is still possible if an attacker has less than half of the computational power [48]. The odds of success are low. A blockchain attack becomes increasingly expensive when the entire network acquires increased hash power. A cryptocurrency with a high network hash rate may also be resilient to 51% attacks. To overcome 51% attacks, several studies and developments are being conducted. Researchers have proposed mixing proof mechanisms to eliminate 51% attacks. For PoW to be applied to a working network, the attacker must gain more than 50% of the processing capacity and more than 50% of the network wealth. This task is highly challenging for a user. In addition, the total cost should be considerably lower than the profit that an attacker might earn. The attacker’s costs are much higher than the benefit in this form of a hybrid network.

Additionally, this hybridisation implements other security measures to counter the attack [28]. Different studies and innovations have recommended different prevention methods, but they have several limitations in common. Komodo [57] introduced dPOW consensus, which takes a snapshot of the blockchain every 10 min and stores it in the blockchain. One of the more recent developments implemented by Horizen at Zen Coin is to delay the block in order to slow down the creation of blocks [29]. Casper and Decred provided a second hybrid PoS consensus using a BFT model with a two-thirds vote mechanism in the first 50 networks. This voting process is independent, resulting in unintended delays and an inconsistent block interval [30]. An alternative hybrid consensus algorithm was proposed by the authors in [31], namely, fork-free hybrid consensus with versatile proof-of-activity and the hybrid PoW-PoS-PoA algorithm. The authors introduced a technique where all PoW chains are created simultaneously and submitted to a committee for review. The committee determines and approves the most robust chain as the main chain. A weighted calculation amongst the committee members determines which chain is the best. On the basis of PoW power and PoS capacity, the weight of each committee member is calculated. This algorithm can also mitigate 51% attacks. However, other issues may affect the blockchain. One of the primary issues is determining how to distribute newly produced block rewards [27]. Another issue is that the interval between block generation is often inconclusive, which is directly related to the recently created currency [49]. Table 2 summarises various hybrid approaches and other solutions discussed in the literature.

Table 2.

Comparison of the proposed hybrid mechanism and other hybrid solutions.

In conclusion, this study proposes a hybrid algorithm that combines PoS and PoW mechanisms to provide a fair mining reward to both the miner and validator. By maintaining a precise block generation interval with difficulty adjustment in power mining and a likelihood measurement according to the stake’s mature stake balance, the system not only resolves the 51% attack but also provides stakeholders and investors with a uniform distribution of mining rewards.

3. Proposed Hybrid Approach

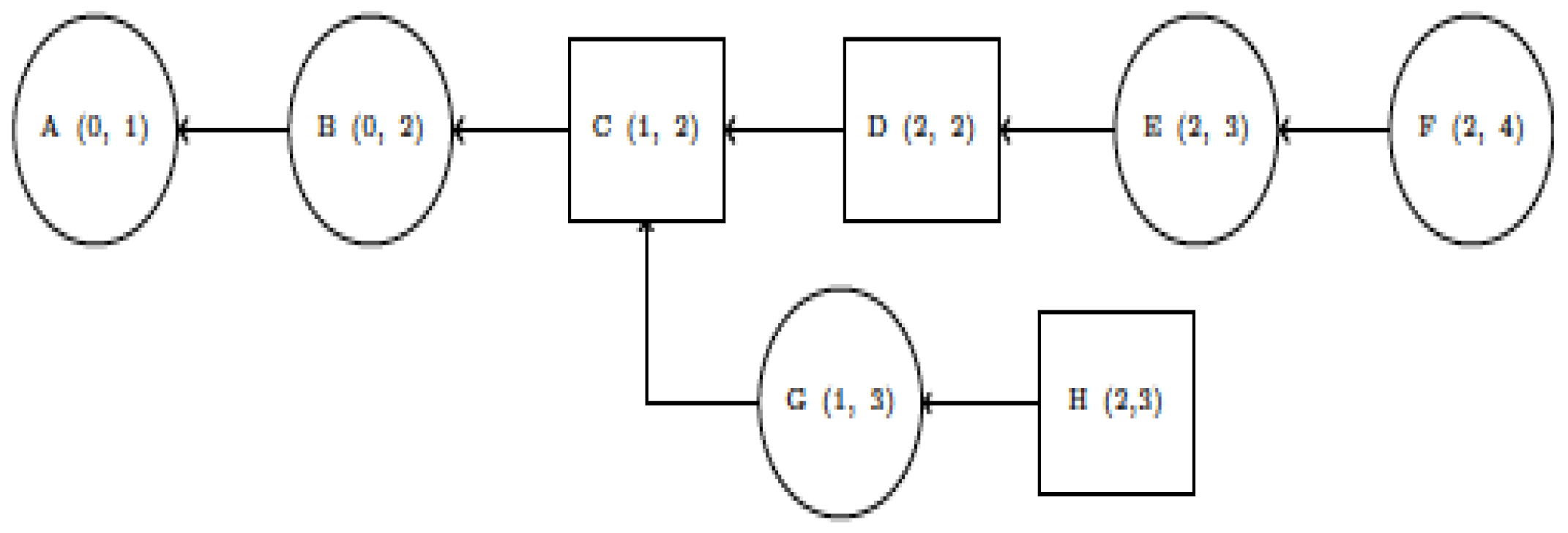

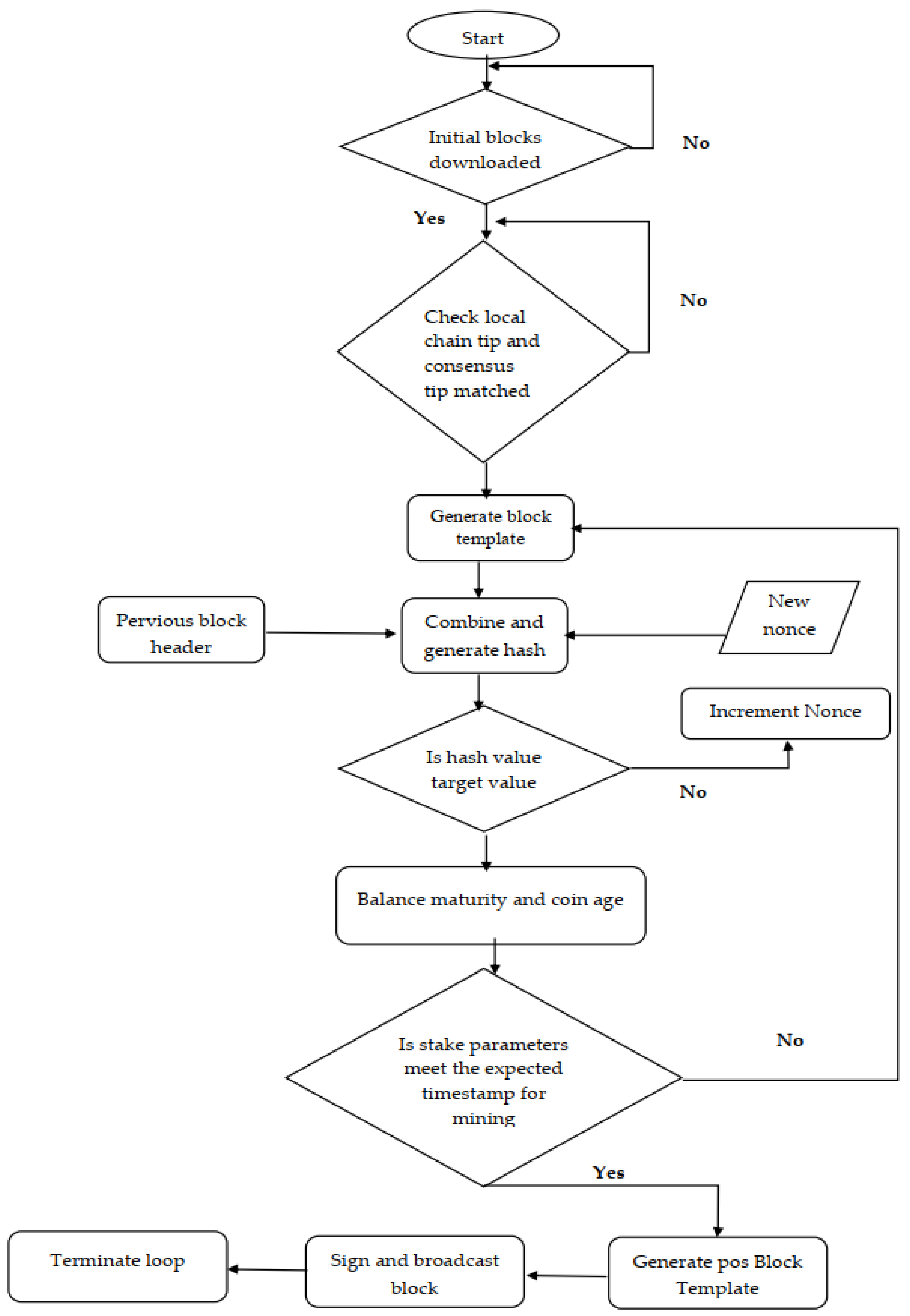

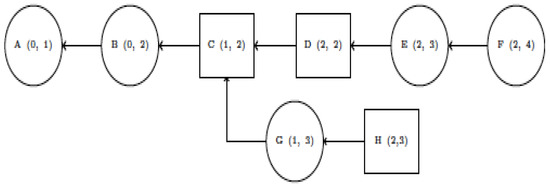

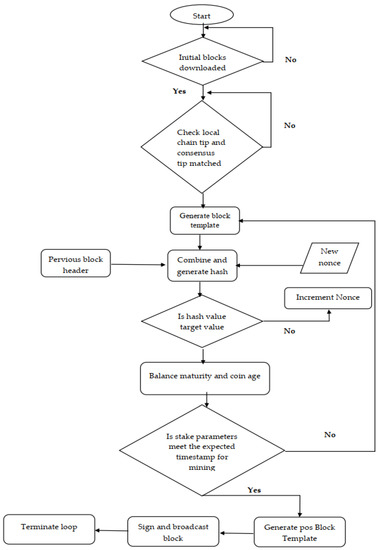

In this study, we combine two consensus mechanisms for a fair mining reward for the miner and validator into a hybrid model. Assume that the behaviour of nodes is likely to be known as the most massive chain. As a result, the first block generated in this model is usually referred to as the main chain, along with the majority of the nodes in the network. In Figure 4, we present our proposed finite state automata (FSA) model for the block-forging process.

Figure 4.

FSA for the block-forging process.

In Figure 4, the square blocks correspond to PoW, and the circles correspond to PoS. The arrows represent canonical chains. Under certain conditions, PoW and PoS blocks are mined and staked in random order, and the possibility of reaching a consensus is approximately 50% [41]. Nx is the set of all positive integers smaller than 2x, and block b = (fp,fsr,ftr,fd,fts,ftx), where fp,fsr,ftr,fd ∈ N256, fd ∈ N64 and ftx is a linked list. Table 3 provides a description of these elements.

Table 3.

Description of the elements of the proposed algorithm.

Miners working in a conventional PoW mining setup require a step-by-step implementation, as depicted in Algorithm 1. With the mining difficulty parameter dw and the 256-bit-long function hash(·), miners can solve complex problems within this rule, as shown in Equation (1).

hit = hash(b) ≤ 2256/dw

After completing mining, several rewards are provided, and their mining power is proportional to the computation power.

| Algorithm 1. Mining for the PoW mechanism | |

| 1 | Procedure MINING PoW (δ) |

| 2 | k ← GetBestChain |

| 3 | z1 ← GetLastBlock(k) |

| 4 | z2 ← GetSecondLastBlock(k) |

| 5 | diff ← GetComplexity(z1,z2) |

| 6 | trxs ← GetMemoryPoolTrxs() |

| 7 | z ← CreateBlockTemplate(k,trxs) |

| 8 | do |

| 9 | thesolution ← ProofofWork(z) |

| 10 | while thesolution > 2256/diffs |

| 11 | z ← Finalize(z,thesolution) |

| 12 | Import & Propagate(z) |

| 13 | end |

Figure 5 illustrates the proposed hybrid model flow, in which the mining process begins with the identification of stake parameters. These are mature balancing parameters for stakes, coinage, the synchronisation of timestamps, the weights of individual nodes and the weight of the entire network. After the initial validations and time sync prerequisite tests, we add the PoW nonce discovery loop. Next, an empty block template is created. The PoW loop then locates a valid nonce to generate a valid hash. The block contains individual transactions that cannot be arbitrarily modified. Other block records, such as timestamps and earlier hash blocks, are irreversible. Therefore, to adjust the hash and achieve a correct pattern, the nodes use the nonce arbitrary field. As part of the PoW loop, miners start with 0 and continue to increase the nonce and produce hashes whilst merging this nonce with other block data. When a correct hash that meets the requirements of the block hash is discovered, the peer achieves success in mining. A complexity factor is added for the block interval to be preserved.

Figure 5.

Process of the proposed hybrid model with supported features.

By applying this approach, we can achieve excellent control over the generation time interval for blocks. In addition, the benefits of mining and transaction fees are evenly distributed amongst investors. Apart from this mining method, another security measure is implemented to secure the network against the misbehaviour of nodes by preventing these nodes in a predefined period. A minimum of one hour is required to ban the simulation setting. Whenever a peer node obstructs, the peer is banned for one hour from the network. The protocol imposes an additional restriction that all nodes must be fairly validated. Both network nodes are equally weighted with regard to decision making. It involves validating a rich node and judging a weak node fairly. The two peer nodes share the same code and weight. Given that the mining process involves a degree of risk, every node can verify transactions and blocks. The frequency of the chance depends on its staking capacity.

Furthermore, our proposed method incorporates PoS and PoW into a stochastic coherence process without sacrificing availability, and a decentralised stack is essential. Considering that the systems run based on computations and stakes in the network, we define a rule-based forking mechanism to ensure that new blocks are produced between the two consensus types. By examining how much effort is made and the rewards obtained by stacker and miner devices, which should be fair, this study demonstrates its novelty. This simulation proposes a minor tweak to the difficulty adjustment, as indicated in Equation (2).

tds, c0 = argmax tdwi · tdsi; i ∈ {1,...,N}

In general, the algorithm chooses the appropriate complexity to match the inside network’s hash/stake power. However, this choice is sometimes gradual. Consider, for example, that stake complexity is approximately 10 times greater than miner complexity. There is a 10x increase in stake in comparison with its hash rate. Unlike PoW, each stacker processes several numbers and keys.

seedt+1 = sign(seedt,sk)

When this condition is met, a stake block can be produced.

where V is the amount of the computation unit and ∆ is the time from the last block. To define the algorithm target, we should have t as the target time and 2t becomes the target time for PoS and PoW. Double-spending attacks take place when an individual has more than 51% of the peer network either as a miner or as a stacker. The dominant attacker is assumed to have power defined with a and b notations, and the ordinary nodes are defined with c and d notations. The hash (PoW) block generation rate is , where (w) is the hash rate. During the simulation, the number of blocks were generated using random variable X ∼ PoS(λw), and E(X) = λw. For example, assume that Yw is a notation of the total difficulty of the mining process; thus, E(Yw) = E(X) · dw.

ln(hash(seed)/2256) | · ds ≤ V · ∆,

Similarly in Algorithm 2, the PoS block generation rate is declared as , where s is the amount of stake.

The notation Ys is the total stack difficulty.

Meanwhile, the attacker’s chain contains a weight within the expected period.

(tdwc + a · t) · (tdsc + b · t)

The ordinary nodes’ rules are defined as follows:

where tdw and tds represent the total difficulty/complexity of mining and stacking blocks, respectively. According to the prospectus of the attacker, overtaking another chain requires the attacker to possess greater power than the normal nodes, which results in network inequality.

(tdwc + c · t) · (tdsc + d · t),

tdsc · (a − c) + tdwc · (b − d) + (ab − cd) · t ≥ 0.

| Algorithm 2. Stacking Algorithm | |

| 1 | Procedure STAKEBLOCK(δ,pk,sk) |

| 2 | k ← GetBestNode |

| 3 | z1 ← GetLastBlock(k) |

| 4 | z2 ← GetSecondLastBlock(k) |

| 5 | stakes ← GetPoStake(k,pk) |

| 6 | diffs ← GetComplexity(z1,z2) |

| 7 | tms ← GetTimestamp(z1) |

| 8 | seeds ← GetSeed(z1) |

| 9 | seeds ← Sign(seeds,sks) |

| 10 | ∆ ← diffs · ln(hash(seeds)/2256)/stake |

| 11 | Do |

| 12 | sleep(1) |

| 13 | While φ < tms + ∆ |

| 14 | trxs ← GetMemoryPoolTrxs() |

| 15 | z ← CreateBlockTemplate(k,trxs,seeds) |

| 16 | z ← Final(z,sk) |

| 17 | Import & Propagate(z) |

Double Spending Attack Prevention Scenario

Only when both a PoW block and a PoS block confirm a transaction should it be considered confirmed on the blockchain. A transaction should not be considered confirmed when only PoS blocks confirm it because PoS blocks can be minted over multiple conflicting chains. As long as people refrain from erroneously considering 1-PoS-confirmed transactions as confirmed, this should not be an issue.

Furthermore, a transaction should not be considered confirmed when only PoW blocks confirm it because this could lead to double spending by an attacker using a 51% attack. This attack is much harder than double spending for someone accepting only PoS blocks as confirmation, but it is likely to be much easier than it is for today’s Bitcoin because the new algorithm reduces the cost of mining (which in turn reduces the system’s hash power by nature). For this reason, both PoW and PoS should be used to confirm or finalise transactions.

The expenditures required to launch a 51% attack are much greater than those for PoW for a given amount of honest mining. Hence, an attacker requires an amount of hash power equal to the honest hash power (which in an equilibrium case results in the attacker possessing 100% of the hash power). In addition, an attacker needs to own a considerable amount of hash stake. Given that the longest chain is determined by multiplying PoW and PoS accumulated difficulties, even if a single miner accumulates 90% of the mining power, it would not be able to produce a significantly longer chain without also owning more than 11% of current coins in circulation.

Considering a scenario in which the attacker attempts to create an additional sidechain and reveals it at a, we assume that the attacker has a hash power and stake power of (a,b), and the fair nodes have (c,d). Let be the total mining difficulty. Then, . This has been given in Equation (1), where the PoS block generation rate , where is the stake and is the total mining difficulty presented in Equation (6). The total mining difficulty is an integration of the hash rate over time and vice versa of the stake over time. In duration , the malicious chain has an expected weight of and the fair nodes’ chain has where and are the total difficulty for PoW and PoS from the genesis block, respectively.

For the attacker to gain the fair nodes’ chain, the malicious nodes need to have a longer chain than the fair nodes’ chain, which further leads to the following inequality: . Given that this attack can only occur if the creation of blocks is free, we assume that the attacker will attempt to attack by using only PoS blocks. Assume that

where indicates the total complexity of the malicious chain. Even if the attacker holds the entire active stake and the total voting power remains unchanged, the best-case scenario is an identical td for the main chain. The projected maximum number of blocks that the LRA can create is because the protocol forbids the creation of new blocks. If an attacker can increase his stake power through block rewards, then his chances of success increase with time. Specifically, the assailant must reach

Assuming that the primary chain’s forging power is static (i.e., not subject to change), is modified to reflect the extra power an attacker would require to equal the main chain’s strength (expressed in difficulty). It must be more challenging than the PoW chain itself. Further research is required to determine how long it takes an attacker to gain access to increased difficulty, but the premise is that this process of gaining power gradually via block rewards occurs over a long period.

4. Experimental Results

During the implementation phase, we set the simulation in such a way that the hash output is uniformly distributed between miners and stakes. The difficulty was adjusted to α = 0.01, the stacker power was set to S = [80, 40, 20, 15, 10, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5] and the miner power was set to M = [32, 16, 8, 6, 4, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2]. Numbers have already been set to show the linearity of the exponential rise in computational power. To begin with, the block time was set to 20 s in t, with a duration of 90 days per entire chain.

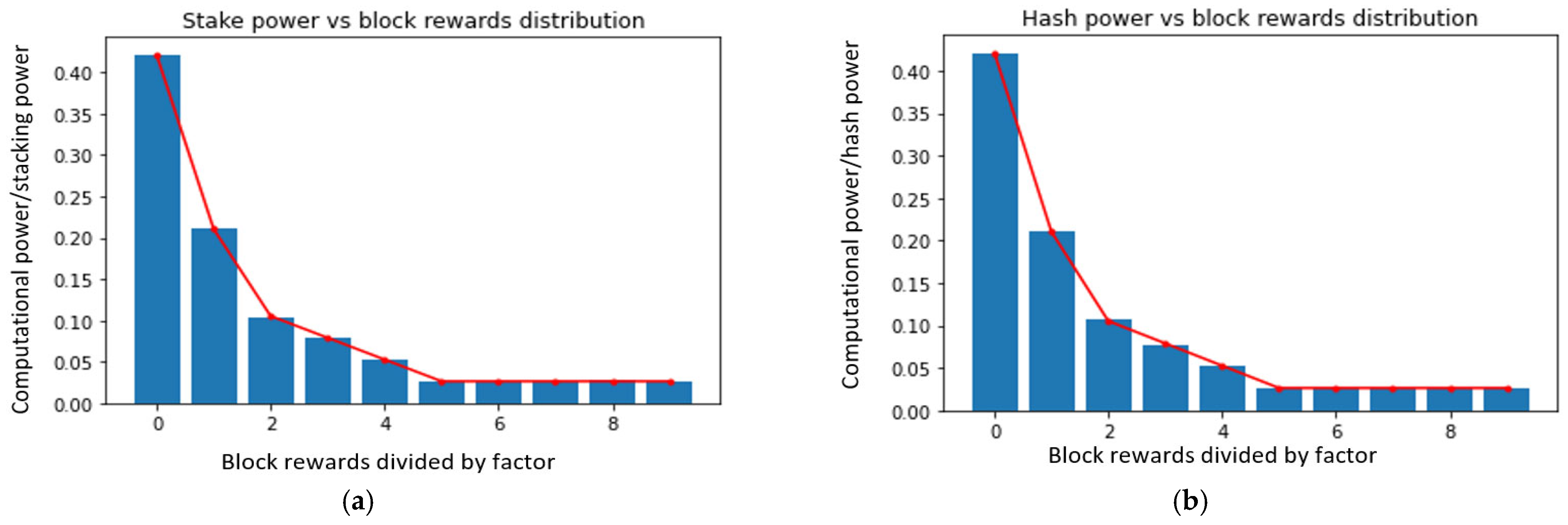

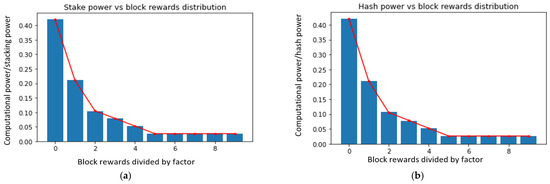

During the simulation, a total of 385,479 blocks were generated, out of which 192,688 were stake blocks and 192,791 were mining blocks. As shown in Figure 6, the rewards were proportional to computing power (stake/mining), which was considered a fair outcome. The target block time was 20 s, resulting in a stake block time of 40 s and a mining block time of 40 s with an average rate of Ps∈S s/ds, Pm∈M m/dm and Ps∈S s/ds + Pm∈M m/dm.

Figure 6.

Experimental results of (a) stake power vs. block rewards distribution and (b) hash power vs. block rewards distribution.

During the experiment, which we ran on the Google Colab platform, we determined that the initial simulation would consume not more than 200 MB of RAM, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Machine computational power.

Figure 6a,b illustrate the stake and hash power results over the block rewards distribution. The mean and standard deviation of time are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mean and standard deviation of time.

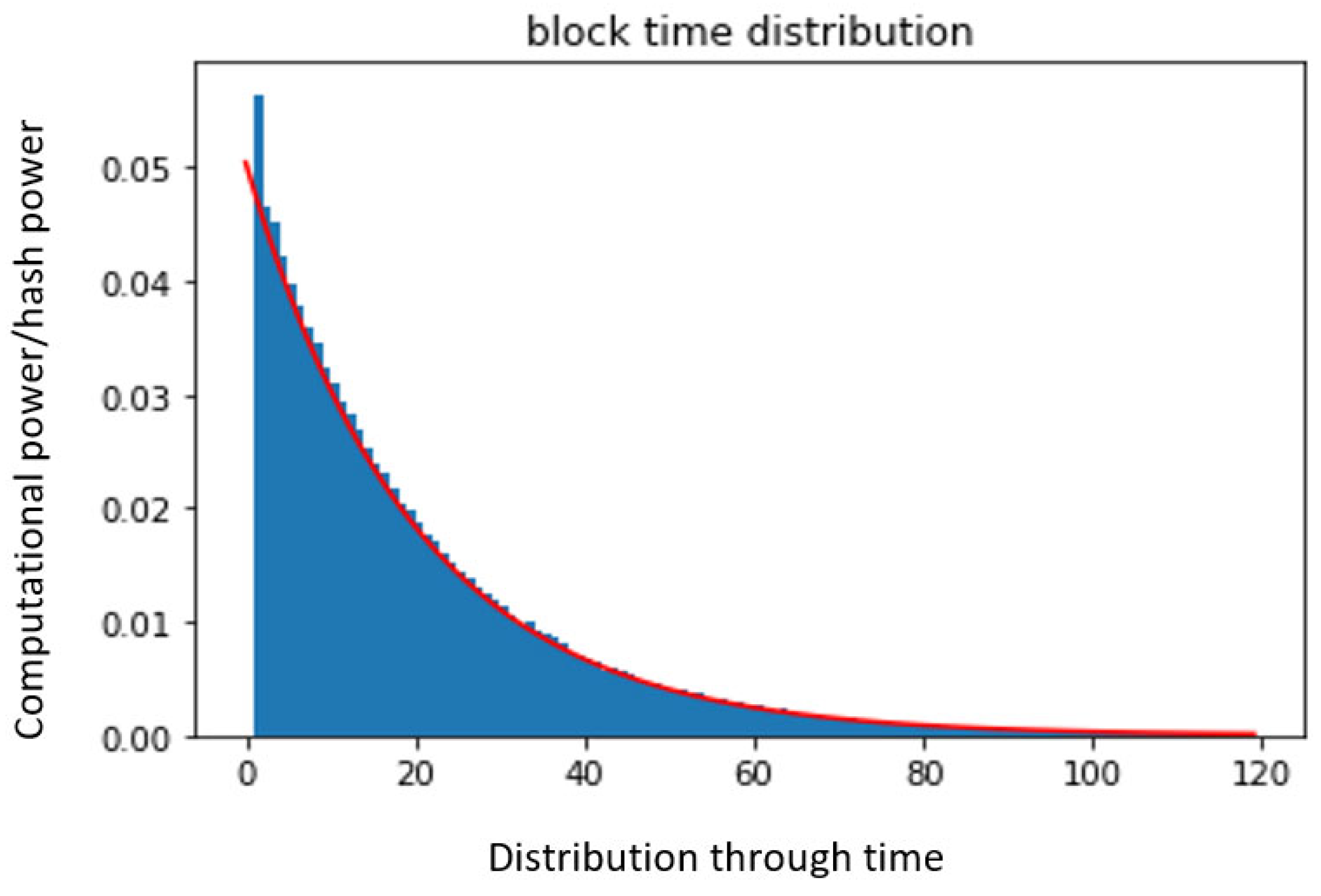

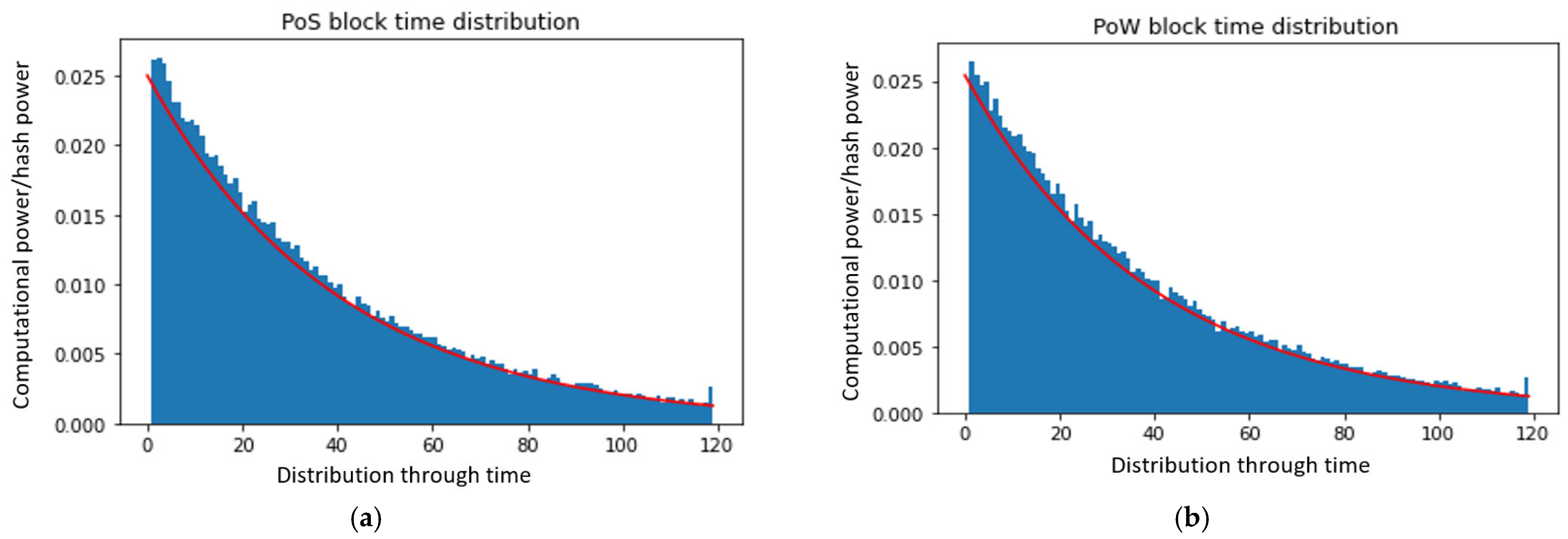

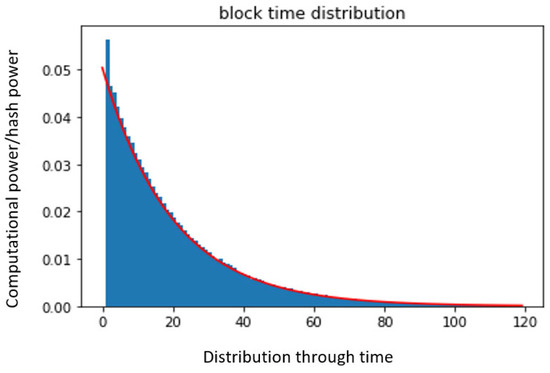

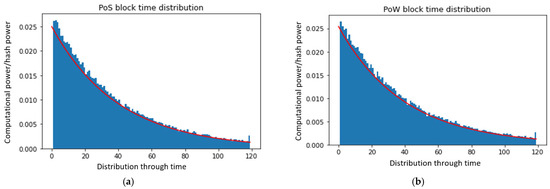

According to the simulation results, the attacker side that dominates the network with more than 51% computation power cannot easily launch the attack because the fork mechanism has a split rule between PoW and PoS implementations. Hence, to take over this network and launch an attack, the attacker needs to command over 100% of the system, which is impossible on a consensus blockchain node. Figure 7 shows that the chain power is demonstrated over the block time generation and distribution, and Figure 8 shows the proposed hybrid model computational power over PoW and PoS block time distributions.

Figure 7.

Power vs. block time distribution.

Figure 8.

Experimental results of (a) computational power vs. PoS block time distribution and (b) computational power vs. PoW block time distribution.

We began the simulation experiment and based on previous data, we set the computational power for mining to 76, which is the same block size. The results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Miners’ computational power before implementing the proposed hybrid mechanism.

Additionally, we discovered that the combined PoW and PoS protocol limits the effective computational power to 52.31. The results of the miner computational power needed for the hybrid mechanism are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Miners’ computational power with the proposed hybrid mechanism (PoW and PoS).

Mining power and actively minting coins may also be used to calculate the attack’s cost. They may be used as a rough estimate of the cost of mining power because they are closely related to miner earnings (fees and coin base incentives). The active stake can be determined because the amount of Satoshi released every second is inversely proportional to the stake difficulty. By dividing the amount of Satoshi issued into equal parts for each PoS block, we can estimate the total amount of Satoshi currently being mined. To compute the income per block required to sustain the attack cost, these measures may be used to determine an attack–cost objective (e.g., a particular number of Bitcoins or a certain percentage of the total number of Bitcoins mined to date). In turn, this information can be used to dynamically alter the block size and ensure that the block income continues to support the set attack cost goal. Therefore, mining earnings will be increasingly predictable, a certain degree of security will be maintained, and costs will be reduced.

The majority of honest minters make the mistake of making coins on a chain that they believe will last the longest, only to have their efforts thwarted by a competitor’s longer chain. This situation means that several law-abiding minters are penalised for minting. If the fine does not exceed the revenue from minting one block, the expected revenue from the effort to mint should exceed zero. A small fee is likely to have a substantial impact, so the projected revenue from minting should be equal to the overall revenue from minting. Ultimately, this depends on whether dishonest minting on a short chain benefits the dishonest minter. Therefore, how much of a penalty should be imposed is debatable.

Given that PoS blocks have little influence on whether an attacker will be successful in performing an orphan-based mining monopoly attack unless the attacker controls a substantial portion of the coins actively being mined, punishing minters who minted over another PoS block would double the collateral damage. Consequently, minter punishment proofs will be invalid if the most recent PoW block is shared by the minted block and the current block. Further research is needed to determine how much stake an attacker needs to possess in order to perform a mining monopoly attack effectively.

If a PoW block has more than one option (e.g., a collision leaving one orphaned), minters may refuse to mint so as to avoid the penalty. If they do so, they will miss out on the most probable benefit of their actions (which would be much greater). Therefore, the likelihood of this behaviour occurring is very low because the predicted benefits exceed 0 by a factor of two.

5. Conclusions

Bitcoin’s popularity and success are primarily related to the underlying blockchain technology, which is a genuinely unchanging and highly protected distributed ledger governed by a peer-to-peer consensus. This study conducted a comprehensive analysis to build the hybrid cryptocurrency PoW-PoS, which can resolve the 51% attack in the most feasible and advanced way possible. The proposed hybrid model can prevent the attack by mixing PoW and PoS in one thread with a strict time spacing for block generation to achieve a resilient and robust agreement amongst P2P network nodes and guarantee a benefit distribution that is in line with stakeholders’ investment ratios. The results showed that we successfully implemented a hybrid consensus protocol for blockchain that combines mining and stacking. The hybrid protocol creates a fair mechanism for miners and stakers. Furthermore, each block’s period is added to provide a double-spending function for every distribution even though the attacker has more than 51% control over the network. We examined the shortcomings of consensus protocols and security techniques to reveal their main weaknesses. A hybrid model that combines PoW and PoS was then successfully implemented. The system incorporates hardware and economic security without compromising availability, predictability or decentralisation. According to the empirical evidence provided in results Section 4, the proposed protocol is fair and scalable to an arbitrary number of miners and stakes.

In the future, we will conduct a more comprehensive analysis of network stability with additional types of miners and stackers and another simulation based on game theory. A highly economical approach for all mechanisms will also be explored in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.A. and A.M.; methodology, N.A.A. and A.M.; software, N.A.A.; validation and formal analysis, N.A.A., A.M. and S.M.F.; investigation, A.M. and S.M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.A. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M.F. and N.E.; visualization, N.A.A. and A.M.; supervision, S.M.F.; project administration, A.M.; Funding N.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Prince Sultan University for paying the article processing charges (APC) of this publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Herbaut, N.; Negru, N. A Model for Collaborative Blockchain-Based Video Delivery Relying on Advanced Network Services Chains. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, J.; Yu, R.; Huang, X.; Maharjan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hossain, E. Enabling Localized Peer-to-Peer Electricity Trading Among Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles Using Consortium Blockchains. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 13, 3154–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Srivastava, G.; Dhar, S.; Singh, R. A decentralized privacy-preserving healthcare Blockchain for IoT. Sensors 2019, 19, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Karamitsos, I.; Papadaki, M.; Al Barghuthi, N.B. Design of the Blockchain smart contract: A use case for real estate. J. Inf. Secur. 2018, 9, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, M.; Shen, L.; Huang, G.Q. Blockchain-enabled workflow operating system for logistics resources sharing in E-commerce logistics real estate service. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 135, 950–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Z. A Blockchain-based framework of cross-border e-commerce supply chain. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Li, Y. Design of evaluation system for digital education operational skill competition based on Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Conference on e-Business Engineering (ICEBE), Xi’an, China, 12–14 October 2018; IEEE: New Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Rong, J.; Wang, B. A privacy protection scheme of smart meter for decentralized smart home environment based on consortium Blockchain. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 121, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Rathore, S.; Park, J.H.; Park, J.H. A Blockchain-based smart home gateway architecture for preventing data forgery. Hum. -Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoom, I.; Zhou, I.; Abolhasan, M.; Lipman, J.; Ni, W. PrivySharing: A Blockchain-based framework for privacy-preserving and secure data sharing in smart cities. Comput. Secur. 2020, 88, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Menon, S.; Nair, N.S. Blockchain Solutions for Security Threats in Smart Industries. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fourth International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC), Erode, India, 11–13 March 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 756–763. [Google Scholar]

- Rathee, G.; Garg, S.; Kaddoum, G.; Choi, B.J. A decision-making model for securing IoT devices in smart industries. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 4270–4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Juels, A.; Shi, E.; Parno, B.; Katz, J. Permacoin: Repurposing bitcoin work for data preservation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Berkeley, CA, USA, 18–24 May 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, R.A.; Li, J.P.; Ahmed, J. Simulation model for Blockchain systems using queuing theory. Electronics 2019, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christidis, K.; Devetsikiotis, M. Blockchains and smart contracts for the internet of things. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 2292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, N.A.; Sunyoto, A.; Arief, M.R.; Cesarendra, W. Reducing overhead of self-stabilizing byzantine agreement protocols for blockchain using http/3 protocol: A perspective view. Sinergi 2021, 25, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, N.; Jin, H. AlphaBlock: An Evaluation Framework for Blockchain Consensus Protocols. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.13289. [Google Scholar]

- Mingxiao, D.; Xiaofeng, M.; Zhe, Z.; Xiangwei, W.; Qijun, C. A review on consensus algorithm of Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Banff, AB, Canada, 5–8 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 2567–2572. [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulos, A.M. Mastering Bitcoin: Unlocking Digital Cryptocurrencies; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Hoang, D.T.; Hu, P.; Xiong, Z.; Niyato, D.; Wang, P.; Wen, Y.; Kim, D.I. A Survey on Consensus Mechanisms and Mining Strategy Management in Blockchain Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 22328–22370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, S. Alt-PoW: An Alternative Proof-of-Work Mechanism. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328150068 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Pilkington, M. Blockchain technology: Principles and applications. In Research Handbook on Digital Transformations; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dannen, C. Introducing Ethereum and Solidity; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Hu, J.; Zhu, T.; Ren, Y.; Choo, K.K.R. A flexible method to defend against computationally resourceful miners in Blockchain proof of work. Inf. Sci. 2020, 507, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanaev, S.; Shuraeva, A.; Vasenin, M.; Kuznetsov, M. Cryptocurrency value and 51% attacks: Evidence from event studies. J. Altern. Invest. 2019, 22, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, S.; Marco-Gisbert, H. Assessing Blockchain consensus and security mechanisms against the 51% attack. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andoni, M.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D.; Abram, S.; Geach, D.; Jenkins, D.; McCallum, P.; Peacock, A. Blockchain technology in the energy sector: A systematic review of challenges and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 100, 143–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Gupta, S.; Dua, A.; Kumar, N. Security of Cryptocurrencies in Blockchain technology: State-of-art, challenges and future prospects. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 163, 102635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor Datta Gupta, A.R. A Hybrid POW-POS Implementation Against 51% Attack in Cryptocurrency System. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337831342 (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Burkhard Stiller, M.F. Communication Systems XII; Department of Informatics (IFI), University of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, S.; Chow, S.S.; Liu, Z.; Long, Y. Fork-free hybrid consensus with flexible proof-of-activity. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 96, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrat, A.A.; Schelén, O.; Andersson, K. A Survey of Blockchain from the Perspectives of Applications, Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 117134–117151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, M. Blockchain Technology and Decentralized Governance: Is the State Still Necessary? J. Gov. Regul. 2017, 6, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui Zhang, R.X. Security and Privacy on Blockchain. Acm Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Q.; Huang, H.; Zheng, Z.; Bian, J. Solutions to scalability of Blockchain: A survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 16440–16455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yu, F.R.; Huang, T.; Xie, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y. A survey on the scalability of Blockchain systems. IEEE Netw. 2019, 33, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertig, A. Cat Fight? Ethereum Users Clash Over CryptoKitties. 7 December 2017. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2017/12/07/cat-fight-ethereum-users-clash-over-cryptokitties/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Niranjanamurthy, M.; Nithya, B.N.; Jagannatha, S. Analysis of Blockchain technology: Pros, cons and SWOT. Clust. Comput. 2019, 22, 14743–14757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliga, A. Understanding Blockchain Consensus Model. 2017. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/da8a/37b10bc1521a4d3de925d7ebc44bb606d740.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Solving the Byzantine Generals Problem with Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS). 2018. Available online: https://www.radixdlt.com/post/what-is-delegated-proof-of-stake-dpos (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Gramoli, V. From Blockchain Consensus Back to Byzantine Consensus. Data61-CSIRO and University of Sydney Australia. 1 September 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319984012 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Gutteridge, D. Japanese Cryptocurrency Monacoin Hit by Selfish Mining Attack. Available online: https://www.ccn.com/japanese-cryptocurrencymonacoin-hit-by-selfish-mining-attack/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Redman, J. Bitcoin Gold 51% Attack. Available online: https://news.bitcoin.com/bitcoingold-51-attackednetwork-loses-70000-in-double-spends/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Tassev, L. Bitcoin in Brief Monday: Zencash Targeted in 51 Hijacked for Ransom. 2018. Available online: https://news.bitcoin.com/bitcoin-in-briefmonday-zencash-targeted-in-51-attackticketfly-hijackedfor-ransom/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Chauhan, A.; Malviya, O.P.; Verma, M.; Mor, T.S. Blockchain and scalability. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security Companion (QRS-C), Lisbon, Portugal, 19–20 July 2018; IEEE: Pisataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Weber, I.; Staples, M.; Zhu, L.; Bosch, J.; Bass, L.; Pautasso, C.; Rimba, P. A taxonomy of Blockchain-based systems for architecture design. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Software Architecture (ICSA), Gothenburg, Sweden, 3–7 April 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Natoli, C.; Gramoli, V. The balance attack against proof-of-work Blockchains: The R3 testbed as an example. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.09426. [Google Scholar]

- Natoli, K. Cryptoeconomics: Paving the Future of Blockchain Technology. 2017. Available online: https://hackernoon.com/cryptoeconomics-paving-the-future-of-Blockchain-technology-13b04dab97 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Gervais, A.; Karame, G.O.; Wüst, K.; Glykantzis, V.; Ritzdorf, H.; Capkun, S. On the security and performance of proof of work Blockchains. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik, K.; Dahiya, S.; Singh, R.; Dwivedi, A.D. Role of Blockchain in Forestalling Pandemics. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 17th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Sensor Systems (MASS), Delhi, India, 10–13 December 2020; IEEE: Pisataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Thin, W.Y.M.M.; Dong, N.; Bai, G.; Dong, J.S. Formal analysis of a proof-of-stake Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2018 23rd International Conference on Engineering of Complex Computer Systems (ICECCS), Melbourne, Australia, 12–14 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Asolo, B. Delegated Proof of Stake (DPOS) Explained. 2018. Available online: https://www.mycryptopedia.com/delegated-proof-stake-dpos-explained/ (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Sharma, A. Understanding Proof of Stake Through Its Flaws. Part 3 Long Range Attacks. 2018. Available online: https://medium.com/@abhisharm/understanding-proof-of-stake-through-its-flaws-part-3-longrange-attacks-672a3d413501 (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Buterin, V. Long-Range Attacks: The Serious Problem with Adaptive Proof of Work. 2014. Available online: https://blog.ethereum.org/2014/05/15/long-range-attacks-the-serious-problem-with-adaptiveproof-of-work/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Buterin, V. The P + Epsilon Attack. 2015. Available online: https://blog.ethereum.org/2015/01/28/pepsilon-attack/ (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- Vitalik Buterin. Selfish Mining: A 25% Attack against the Bitcoin Network. 2013. Available online: https://bitcoinmagazine.com/articles/selfish-mining-a-25-attack-against-the-bitcoin-network-1383578440/ (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- ChainZilla. Solutions to 51% Attacks and Double Spending. Medium. 2020. Available online: https://medium.com/chainzilla/solutions-to-51-attacks-and-double-spending-71526be4bb86 (accessed on 13 October 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).