Abstract

The aim of the study was deepening the knowledge of livestock innovations knowledge on small-scale farms in developing countries. First, we developed a methodology focused on identifying potential appropriate livestock innovations for smallholders and grouped them in innovation areas, defined as a set of well-organized practices with a business purpose. Finally, a process management program (PMP) was evaluated according to the livestock innovation level and viability of the small-scale farms. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the impact of PMP on the economic viability of the farm. Information from 1650 small-scale livestock farms in Mexico was collected and the innovations were grouped in five innovation areas: A1. Management, A2. Feeding, A3. Genetic, A4. Reproduction and A5. Animal Health. The resulting innovation level in the system was low at 45.7% and heterogeneous among areas. This study shows the usefulness of the methodology described and confirms that implementing a PMP allows improving the viability an additional 21%, due to a better integration of processes, resulting in more efficient management.

1. Introduction

Small-scale farms represent 19% and 12% of the world’s production of meat and milk, respectively. The dual-purpose (DP) bovine farms in the tropical region in Latin America constitute key organizational mechanisms in terms of security, supply, access and stability of food [1]. These smallholders live on the threshold of poverty and marginalization, within very fragile ecological systems, although with great potential for mitigating emissions of greenhouse gasses as a consequence of their low dependency on external inputs. Also, these farms represent a factor for economic feasibility, social cohesion and poverty reduction [2]. The DP system offers high degrees of resilience of its agroecosystems and it remains the prevalent model in poor countries. Also, it increases the level of diversification of livelihoods and strengthens synergies among productive activities [2]. A distinguishing characteristic of small-scale farms is their flexibility to face both climate and economic changes as a consequence of low levels of investment that might allow replacing dairy with other productive activities to assure the subsistence of the smallholder’s family, i.e., during wide drought season (around six months), the farmers may sell the cattle stocks and buy them again at any other better time [3]. This flexibility, coupled with the ability to generate cash, regularly permits this system to be one of the widest-spread activities in rural areas of Latin America, Africa and the Mediterranean basin [4].

Agriculture Innovation

According to [5], innovation is a process by which new ideas are transformed into practices. In agriculture, innovation was defined in the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa by [6] as “the activities and processes associated with the generation, product distribution, adaptation and use of new technical and institutional/organization knowledge” [7]. We define innovation as an integrated system to improve agricultural productivity and agroecosystem resilience, involving different agronomic and management components within a synergistic relationship. In the same way, [8] indicates that agricultural innovation presents a dynamic view and is seen as a complex and collaborative system.

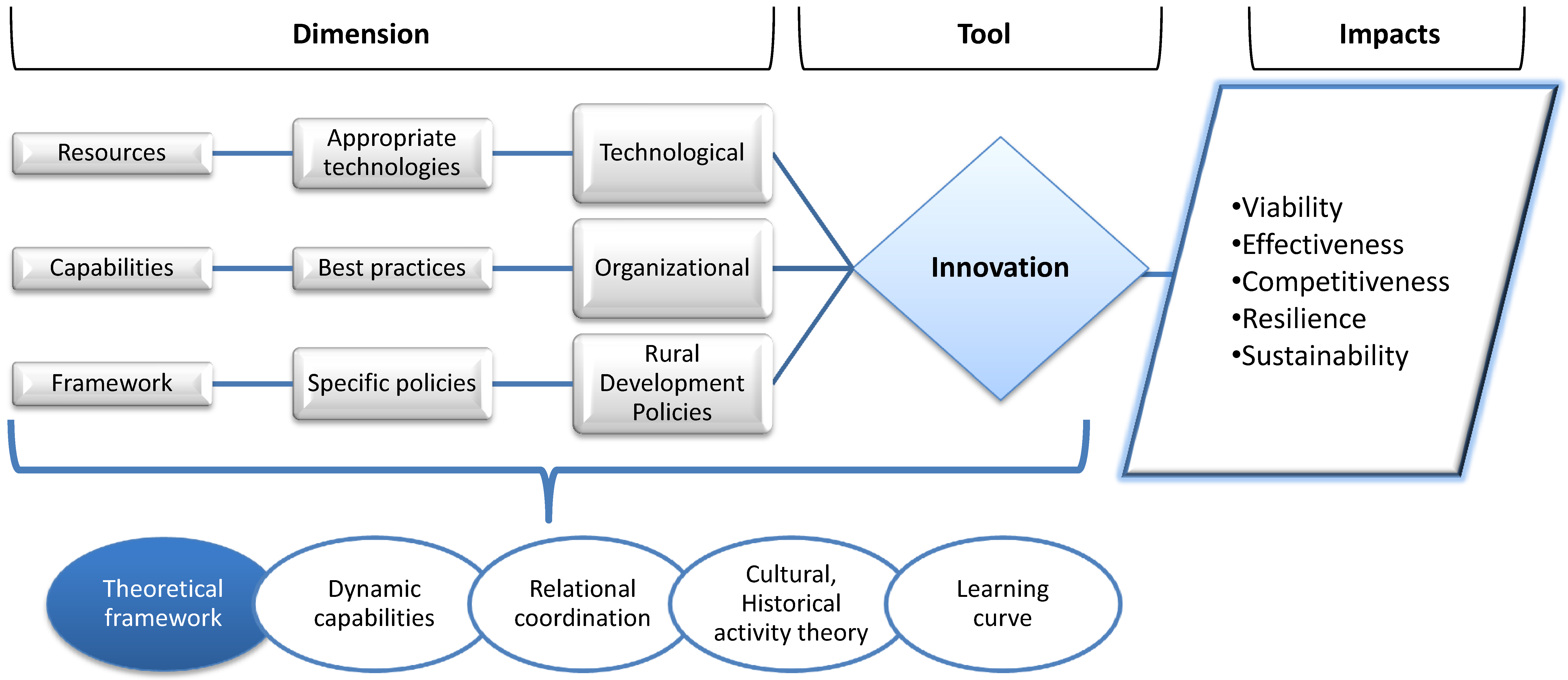

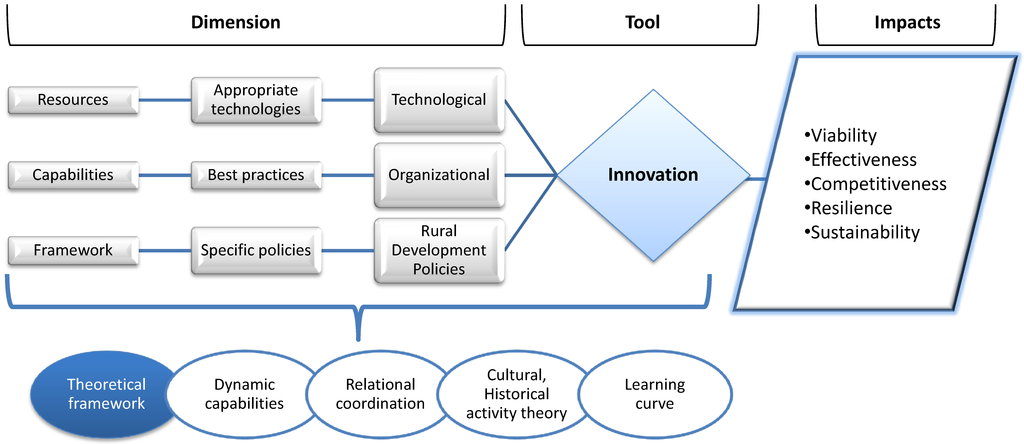

Innovation is a tool that can increase the competitiveness, viability and effectiveness of farms (Figure 1). An innovation should be socially useful, appropriate and economically viable [9,10]. When innovations are implemented by considering the technical, human and organizational resources, the dynamic capabilities and the strategic positioning of the farm will be enhanced [9]. According to [11], the innovation process allows identifying appropriate technologies and best organizational practices, which will be transferred for satisfying specific needs of the productive activity [12] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dimensions of innovation in the agricultural sector.

Developing the livestock innovations (LI) concept implies improving processes and products from the holistic knowledge of the system [13]. In this way, the background of strategic management could be applied in agricultural innovation [9]. In order to create dynamic capabilities in organizations, the relational coordination framework [11] and the learning curve of innovation [14] can be considered (Figure 1).

The livestock innovation level has been previously developed in mixed systems, such as dual-purpose bovine [15], sheep-crop [16] and mixed agriculture [8,17]. In the DP system, the innovation level depends on several factors [12,18], i.e., farm size (size of herd or surface), ecological zones, culture, etc. [19], which indicate that an increase of farm size improves production, intensification, and the innovation level. In regard to cultural factors, [7] associate an increase of technological level to higher levels of education. According to [20]: “Farmers need to innovate in their system; governments need to innovate in the specific policies they implement to support family farming; producers’ organizations need to innovate for a better response to the needs of family farmers; the researchers and extension advisors need to innovate shifting from a research driven process predominantly based on technology transfer to an approach that enables and rewards innovation done by smallholders themselves”.

As such, some questions arise:

- Why do a lot of farmers not adopt the innovation?

- What is the main reason for failure in the adoption?

- What is the real level of innovation in the farms?

- What are the key technologies and practices for reaching success?

The use and adoption of innovation are the result of knowing the objectives of the farms, the agroecosystems’ limits and the synergies between different activities [4,21]. In this way, [2] indicate the importance of deepening the knowledge of objectives, potentials, limitations and “right of being” of the farms. These systems can be optimized by taking into account economic, social and environmental dimensions. Moreover, the farmer’s profile (socioeconomic, managerial capacities, access to information, etc.) must be considered in the development of policies [22].

Knowing how an innovation has been generated and spread to the farmers is recognized to be another key factor in the success or failure of the innovation [11]. The traditional views of top-down and the current bottom-up are not sufficient and they propose joining both strategies to deal with the lack of an innovation paradigm in South Africa [8]. In addition, according to this author, farmers do contribute to innovation and should be treated as partners in agroecological innovation.

Many technological transfer projects have failed because leaders often have little background to prepare them and to identify the conditions to be successful [23]. It is necessary to provide support to the advisor for evaluating ex-ante the potential consequences of innovation on the structure, functioning and performance of a farm [13]. The choice of innovations and their effects in the production constitute the key challenges that can favor the development of the livestock and the increase of competitiveness of smallholders [10,16,24].

Therefore, the objective of this research is developing a methodology to deepen the knowledge of livestock innovation. In a first step, innovations are identified by asking the farmer if certain innovations have been implemented and by measuring the innovation level acquired in the farms [25,26,27]. Later on, the impact of innovations on the farm’s performance will be evaluated.

2. Framework of the Methodological Approach

What are the objectives of smallholders?

According to [28], smallholders seek food security, family welfare (including education), and reduction of vulnerability and poverty by applying a low-cost strategy and low levels of innovation. Most of the farms are of a small-scale size and subsistence (85%), and only the 15% of the smallholders have business objectives, oriented to market. Moreover, livestock is the farm asset that potentiates food stability and supports the expansion and diversification of activities [29]. The objectives and strategies are similar in the mixed cereal-sheep system of the Mediterranean basin [12], the dual-purpose bovine system of the American tropic [14] and the small-scale farms in South Africa [26] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Objectives of smallholders in developing countries.

2.1. Steps of Methodological Approach

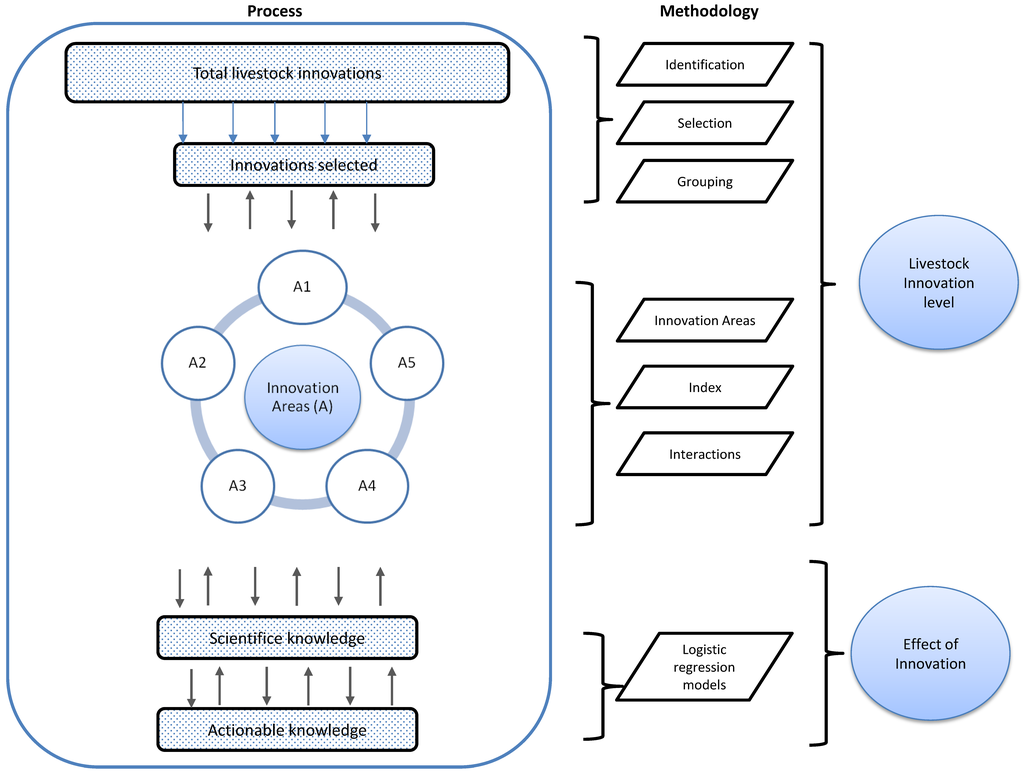

A livestock innovation index was built utilizing qualitative methodology according to [13,33]. The methodology included features such as collaboration, cooperation, consensus, transdisciplinary research strategy and taking into account different stakeholders of the value chain. This methodological approach provides researchers a first insight about the innovation level of the system. Subsequently, this methodology will deepen knowledge of the impact of an innovation on the performance of the farms through quantitative analysis [32].

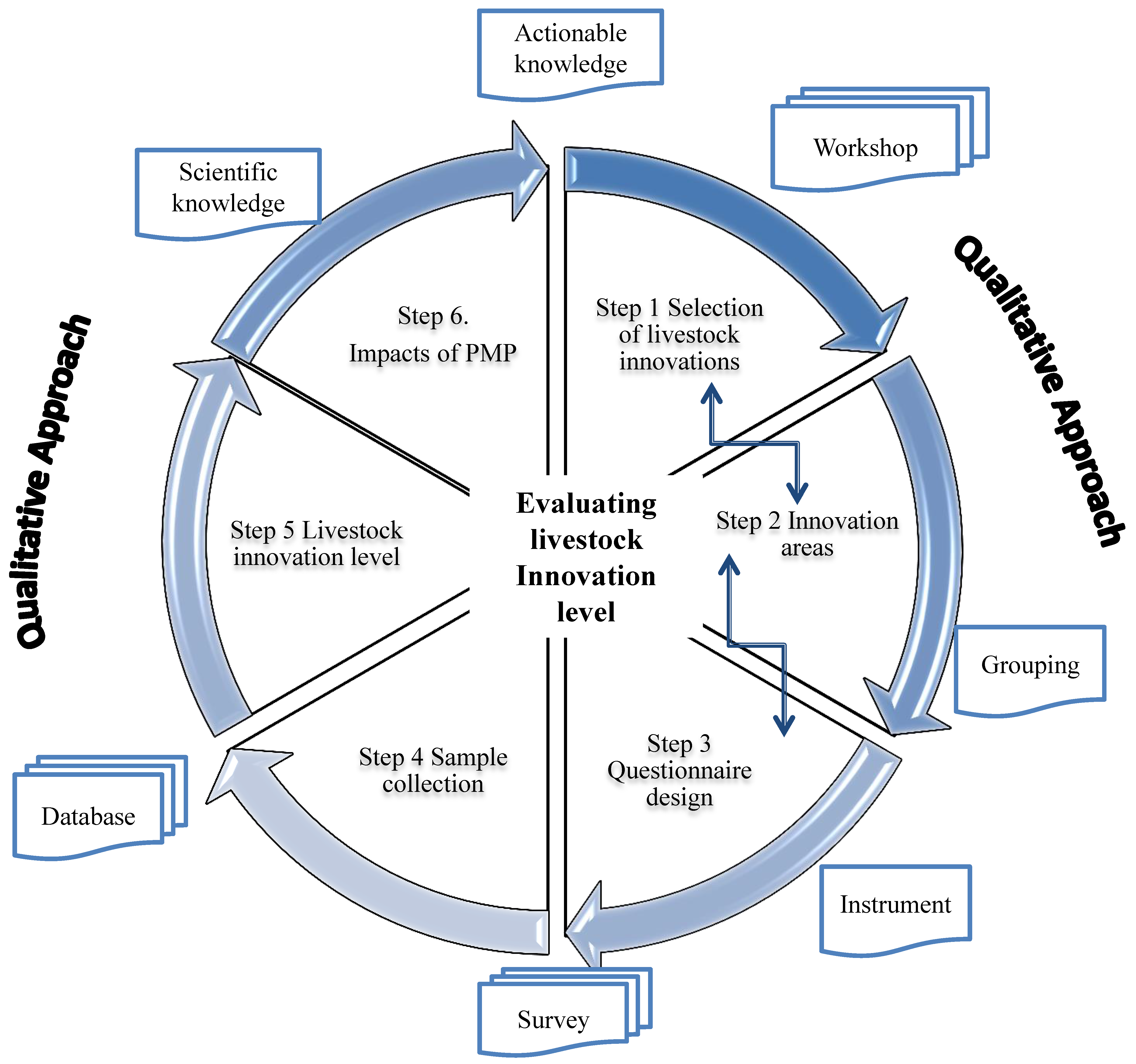

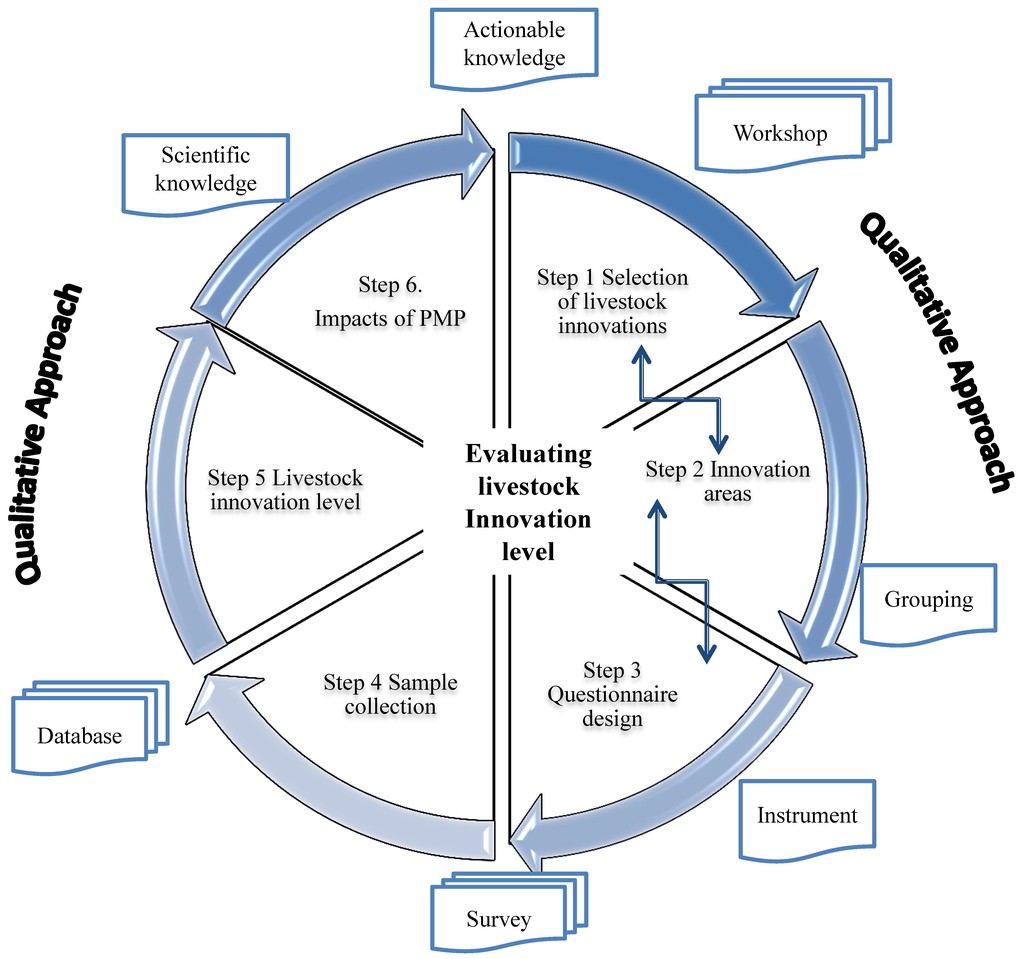

Figure 2 shows the process to evaluate the livestock innovation level starting with the identification and selection of relevant innovations. Subsequently, the selected innovations will be grouped in areas into a program of process management for their evaluation [9]. The methodology is composed of six steps: identification of technologies, grouping in areas, building of a tool or instrument for field research, information gathering, building a database and indicators. Finally, through quantitative methodology, the effects of livestock innovations on viability are evaluated [8,12].

Figure 2.

Steps for evaluating livestock innovations on small-scale farms.

Step 1. Identification of innovations

First, a pre-selection of livestock innovations was conducted according to their relevance for the DP system. The pre-selection was based on an extensive literature review; in addition, information in situ from the smallholders was gathered. In this way, 185 potential technologies for DP systems were pre-selected. Subsequently, during a workshop with the presence of the experts, each pre-selected technology was analyzed and discussed according to its relevance in the Mexican DP context.

The panel of experts was constituted by 14 specialists in livestock production: six university professors specializing in different animal production subjects such as nutrition, economy, animal welfare, health, rural policies and milk quality; five technical advisors; and three researchers specializing in milk production, animal nutrition, and reproduction. The experts presented around an average of 20 years of experience with different profiles as veterinarians, agronomy engineers, economists, chemistries, and biologists.

During the workshop, the meaning of each variable was explained to the experts’ group (Table 2), including how the values were obtained, their importance for the productive process, the consistency of the innovations and the number of farms with the innovation, among others. The following issues were also raised at the working session:

- -

- How has the adoption process been developed?

- -

- Are the livestock innovations properly used?

- -

- What were the reasons for success or failure for the use of livestock innovations on the farm?

Table 2.

Innovations and areas in the dual-purpose system.

In addition, the technical, financial and human requirements of each innovation were evaluated [34]. Later, the experts assessed each identified innovation by a Likert scale with values from one to five, where one was the least important and five the most important (Appendix 1). In the first round of assessment, those technologies which obtained the maximum score (five) in the opinion of nine or more experts were selected and the technologies with a minimum (one) qualification from nine experts were discarded. In the second round, descriptive information from the set of responses (concordance index and mean) was sent to each expert for re-examination and reconsideration of their judgment. The Ishikawa index was utilized considering a concordance level where the livestock innovations with greater than 60% of the concordance level and an average score over 3.5 were selected [35]. In Table 3, the innovations selection survey is shown.

Table 3.

Selection of livestock innovations and innovation areas.

Step 2. Grouping of livestock innovations in areas

In this stage, the selected livestock innovations from step 1 were grouped in areas according to [3,15,17] and following the methodology proposed by [9] in mixed systems. The proposed areas could be internationally useful in tropical places with dual-purpose bovine and small-scale farms, so over 50 experts from several countries were consulted online.

Initially, 15 areas were proposed: feeding, reproduction, genetics, global change resilience, animal welfare, management, production, grasslands, milk quality, animal health, public health, economy and markets, farm facilities, labor, social items, associations and sectoral policies. The selected livestock innovations were presented to the experts, so they could suggest new areas for the list (Appendix 2). Once the expert’s suggestions were incorporated, the process of selecting areas started, following these criteria: (i) every selected innovation must be classified at least in one area; (ii) the set of innovation areas must be as small as possible. In the second iteration, the proposed areas were shown to the experts for their assessment and selection. In the third round, descriptive information from the set of responses (Kendall’s index or the coefficient of concordance W) was sent to each expert for re-examination and reconsideration. In this round, five innovation areas were selected (Table 3).

Step 3. Questionnaire

According to the mixed systems studies from [12,15,24,31,36], a questionnaire was designed to capture information from each farm regarding the identified innovations. The questionnaire was previously validated in six pilot farms (two questionnaires by each type of farm as described in Table 1) and subsequently improved. The questionnaire was adjusted for each innovation and grouped according to experts’ recommendations. The survey included between 284–300 items related to the subjects: sociology (9%), facilities (11%), reproduction (11%), feeding (13%), farm structure (10%), animal health (11%), market and economy (36%).

Step 4. Information gathering

A sample of 1650 smallholders’ DP farms with 50 or fewer cows in production [16,18] was selected during the year 2011. Data were obtained from questionnaires applied directly by trained technical advisors from the livestock support program of SAGARPA (Mexican Minister of Agriculture) [10] to smallholders and included 45 livestock innovations. The average time for survey application was around 5.5 h per farm, similar to that reported by [12].

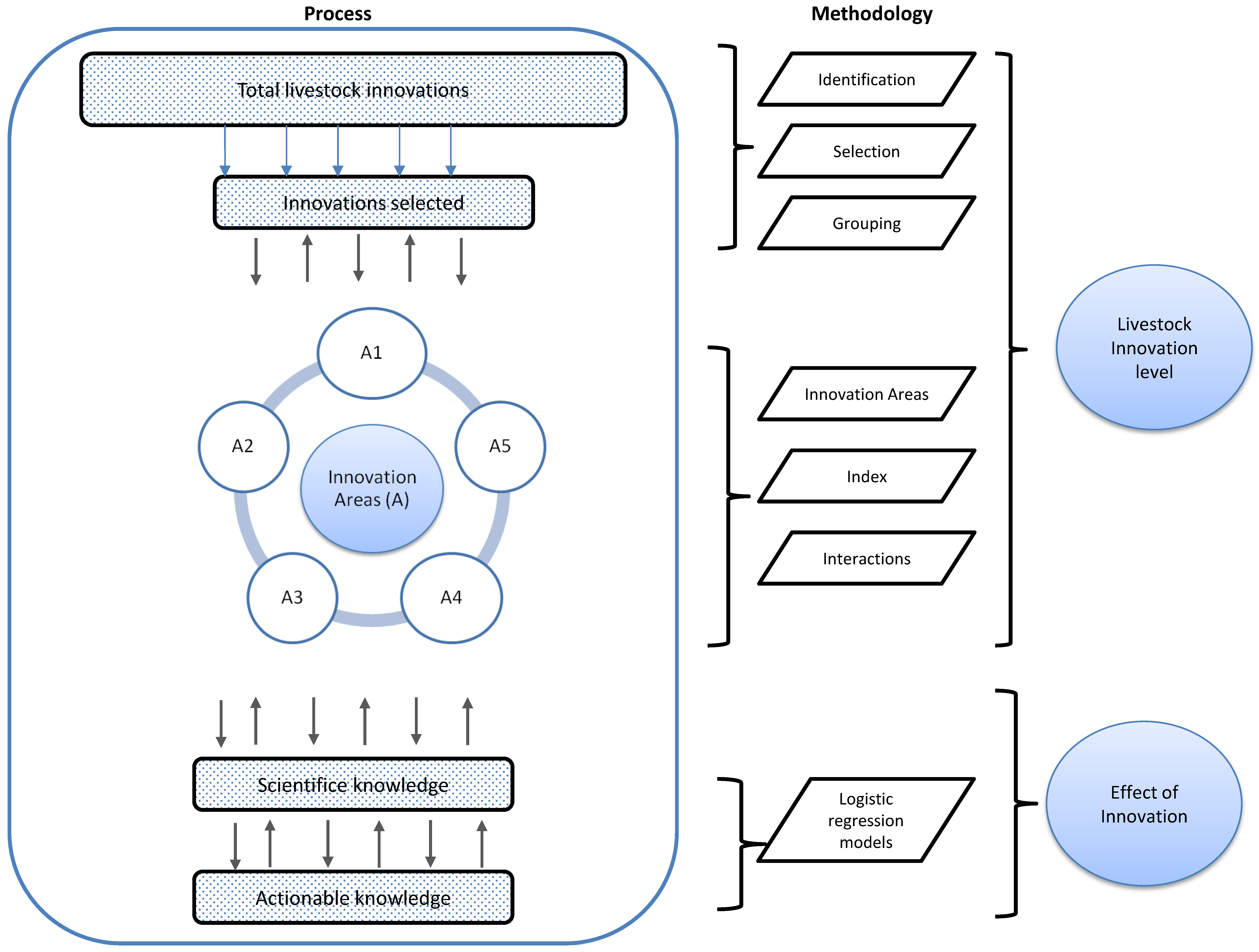

Step 5. Livestock innovation level

Figure 3 shows the innovation assessment process used in the dual-purpose bovine system in tropical regions [15,16]. One innovation index was calculated per each area [12,15]. It was based on the proportion of innovations implemented over all innovations identified. The process areas were classified using multiple-sample comparison and the significant differences between groups were analyzed with the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Subsequently, the existence of the association between areas was verified by Spearman correlations.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of livestock innovations.

Step 6. Impact of innovations, viability and the process management program (PMP)

Viability is an aggregate index that incorporates productive, economic and social factors [3,24]. The viability of each farm was calculated according to its ability to generate sufficient profits for guaranteeing the maintenance of the family unit over the long term (positive net cash flow during three consecutive years) [37]. If a farm generated a positive economic return during three consecutive years, it could be considered as viable (Viability = 1), and non-viable in the other situations (viability = 0).

2.2. Process Management Program (PMP)

The process management program (PMP) is a strategic tool for improving farm performance outcomes and its operational agility through improving management processes. The PMP spans organizational boundaries, links farmers, and enhances information flow systems and other assets to create and deliver value to stakeholders such as customers, smallholders, and consumers [32]. The PMP was applied from grouping livestock innovations in the defined areas in step 2. For Mexican DP farms, the PMP was utilized through a livestock innovations technology transfer model, known as GGAVATT (farming livestock groups for the validation and transfer of technology). Since 1996, the GGAVATT model was developed by INIFAP in México, who were given technical assistance through an SAGARPA support program in 2011/2012 [10]. The GGAVATT model is based on active participation of farmer groups with similar production objectives. Also, in the model, the innovations developed in research centers were validated, transferred and adopted by the farmers in collaboration with other stakeholders, such as advisors, researchers and agricultural governmental officials, among others. The activities include tools such as participative diagnosis, planning, efficient use of resources, selection, implementation of innovations and results evaluation. The GGAVATT model is based on training farmers in organizational routines (collecting productive, reproductive and economic records) and it has use in the decision-making oriented to management, animal feeding, genetics, reproductive planning, health programs, milk quality, etc. These procedures are integrated into a transversal schema by following the specialization approach of the particular farms’ objectives (milk, meat, cheese, etc.). This approach allows following an ordered and logical sequence of activities [9,38].

2.3. Impacts of Innovations

A binary logistic regression analysis has been applied to evaluate the impact of the PMP on the economic viability of the farm. The model is as follows:

In the model, the dependent variable, viability, is dichotomic (1/0) and it represents the viability of farms; the independent variable is whether the PMP is implemented (category = 1) or not (category = 0). The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to evaluate the fit of the model. The odds ratio (OR) and its confidence intervals (IC = 95%) were calculated to quantify the association between both variables. For the statistical analysis, SPSS 19.0 software was used.

3. Results

Table 4 shows that the average of the technological innovation (TI) level was 46.3% with an uneven behavior between areas, and four different groups were configured (p < 0.01) (Table 4). The highest TI level was viewed in A5 animal health (72%). On the opposite side, the lowest levels were found in A2 animal feeding and A4 reproductive management with 28.3% and 27.4% respectively. In addition, these two areas showed high coefficients of variation, 52.2% and 70.9% respectively. Similar patterns of technological adoption in animal health and reproduction were found by [9] in Ecuador, [10,39] with smallholders in México and [26] in Ethiopia. The efforts in improvement of animal health are based on the use of technologies for parasite control, sanitary governmental programs and the quality requirements for the dairy industry.

Table 4.

Livestock innovation level (mean ± standard error) for each area (A).

Low levels of Spearman correlations were identified (p < 0.05), and were significant (p < 0.01) between the 10 pairs of areas. The highest levels of correlations were found between A5 health and A1 management, and A2 feeding and A4 reproduction, with r = 0.35, r = 0.36, and r = 0.35, respectively. Moreover, A1 management showed high correlation levels regarding A2 feeding, and A5 health, with r = 0.40, and r = 0.35, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Spearman correlation matrix among innovation areas.

Of the producers, 56% have implemented the PMP and 44% did not. The results of the binary logistic regression are shown in Table 6 and confirm the positive association between PMP and the economic viability of the mixed system. The model estimates that the likelihood of being viable economically is 5.059 times higher when a PMP system has been implemented. The Hosmer and Lemeshow (p = 0.837) test does not proof the absence of fit of the model, which was correctly classified in 70% of the cases. The Nagelkerke (0.176) determination coefficient and the Hosmer- Lemeshow statistic (2.7649) suggest that a PMP program explains 21% of the economic viability of farms.

Table 6.

Odds ratios of included variables based on a logistic regression on the viability of farms.

The second estimated model for the farms that implements a PMP (Table 7) is explained by the five innovation areas with a 62% accuracy in prediction and a Nagelkerke R2 of 0.235 and an H-L Statistic of 7.540 (p-value Chi-Sq = 0.480). This indicates that the model is accepted to describe the probability curve of the variability of the farms with PMP. In the suggested model, the innovation area of feeding (p < 0.05) is shown as the explanatory variable of the viability of PMP farms; the estimated OR value for A2 feeding is 1.080, meaning that when a farm adopts a technology from A2 feeding, it has an 80% of possibility of being viable.

Table 7.

Odds ratios of included variables based on a logistic regression on the viability of farms with PMP.

4. Considerations and Implications

The methodology that has been built allows us, first, to identify innovations; second, to group them in innovation areas; and third, to build an index and assess the impact of the innovation. This approach is utilized as a tool for increasing knowledge and improving it for small-scale farms [40,41]. This methodology is developed in three stages: firstly, a participative methodology proposed by [12] that enables the building of synthetic indexes from a group of variables is used. Other studies use a similar methodology in livestock mixed farms on the Ecuadorian coast [12], Mexico [27] and Spain [37]. In the second stage, the data were collected. Finally, logistic regression was used to assess the impact of innovation. It was focused on the importance of implementing a process management program on the viability of the farms [25]. Nevertheless, other authors propose other quantitative methodologies to analyze the innovation [4], such as principal components, cluster analysis and structural equations. Also, the use of these methodologies could improve the results achieved.

The association among process areas through Spearman correlations has been confirmed, according to [26] in Ethiopia and [15] in Ecuador. Independently from the used innovation, the innovation must be studied as a systemic-organizational approach, which considers all innovation areas. It is based on several attributes of the system, such as adaptive and holistic character [34]. Moreover, positive interactions were found among the different areas and the implementation of new innovations often requires promoting a process management program that allows reaching an adequate level of innovation adoption [9]. The authors of [23] indicate than innovation is not a linear process; on the contrary, it is very interactive, collaborative, collective, transdisciplinary and requires the consensus of several stakeholders [11,15].

The development of this mixed methodology, both qualitative and quantitative, implies an approximation between science and reality, with a growing preoccupation with the improvement of government policies for rural development and the challenges faced by the smallholders and family farms (viability, food supply, food security, etc.). According to [23], in order to deepen the new paradigms, the question mainly is: what are the links between livestock, food industry, science and rural livelihoods for small-scale farms?

The obtained results agree with [31], who found that the innovation level in agriculture depends on the flows of knowledge and the quality of the linkages between producers and other agents of the value chain. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD 2011 report considers that most of the smallholders lack appropriate technical assistance for innovation adoption [39]. In this way, [36] estimate that only between 3% and 10% of smallholders in Mexico get technical assistance. This value is very low, regardless of the quality of the service, the process of adoption, the impact, and the used innovation consistency. The authors of [42] indicate that the promotion of innovations by technical advisors is necessary; apart from this, there are external and internal financial factors that address the success of technological adoption.

Livestock innovation in developing countries requires a systemic approach as a priority, where all activities on the farm are considered independently of the direct productive results, because the farms have different objectives and strategic challenges, as has been shown in Table 1 ([1,19,30,31,32] among others). Most farmers are small-scale, with a low or null technological innovation level, and have an urgent need for technical support and a perception of “nothing changes”. There is a constant dilemma: are the subsidies a tool for inequality [43]?

Therefore, this research seeks to identify the pathways for innovation in order to enhance the desired impact in the smallholders’ livelihoods and to link the innovation to the improvements in economic, social and environmental results [25]. The developed study is prospective and preliminary, although the innovation areas’ impact is verified on the farms’ viability. Different studies have shown that the process management program (PMP) develops a very important role in the profitability of farms for the adoption of technology and managerial practices [10,15,37,44]. However, the PMP is not directly observed or measured, and furthermore, its effects are multi-factorial and hierarchical. This situation makes it difficult to develop statistical models that allow analyzing its causal diagram [37]. The usefulness of the proposed logistic model resides in its capacity to establish associations among the managerial factors (PMP) and viability, although the knowledge of the mechanisms that underlie the mixed systems’ interrelation is insufficient [45]. The results are interpreted as correlated approaches and they indicate that the implementation of the process management program favors the economic viability of the farms. Future studies should be oriented to the synergies that appear among the management of processes, the economic development and the environmental sustainability, as indicated by [46], in the long term. Apart from this, [47] indicate that PMP contributes to corporate responsibility by orienting the processes according to the needs of smallholders, and it constitutes a factor for social sustainability.

Acknowledgments

This work has been developed within the “Open Innovation Network in agri food sector” and it is the result of collective action and collaborative innovation among researchers from the University of Córdoba and University Rey Juan Carlos (Spain), the Central University of Venezuela (Venezuela), and the National Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Institute (INIFAP) (Mexico). The data of dual-purpose bovine farms are from Project Adoption and evaluation of implemented technology on dual-purpose bovines of México” SIGI 21541832011 funded by “Fondos Fiscales-INIFAP.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1. Assessment Innovation in Mexico

Following the meaning of the values described below, point out the next: 1 lowest importance to 5 greatest importance. According to your opinion: The uses of innovations in dual-purpose systems have importance…”

| N | Innovations | Assessment 1(less)→5 (plus) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | Animal identification | |||||

| 2 | Record system | |||||

| 3 | Breeding management | |||||

| 4 | Grazing native pasture | |||||

| 5 | Grazing planting | |||||

| 6 | Grazing of crop residues | |||||

| 7 | Milking season | |||||

| 8 | Type of milking | |||||

| 9 | Green fodder | |||||

| 10 | Silage | |||||

| 11 | Hay making | |||||

| 12 | Processed feed | |||||

| 13 | Concentrate making | |||||

| 14 | Molasses/urea | |||||

| 15 | Grains and oilseeds | |||||

| 16 | Multi nutritional blocks processed | |||||

| 17 | Manufacture of multi nutritional blocks | |||||

| 18 | Common salt | |||||

| 19 | Mineral salts | |||||

| 20 | Mineral blocks | |||||

| 21 | Vitamin provided | |||||

| 22 | Agro-industrial by-products | |||||

| 23 | Using male breeds | |||||

| 24 | Using male crosses | |||||

| 25 | Using female breeds | |||||

| 26 | Using female crosses | |||||

| 27 | Use of genetically tested bulls | |||||

| 28 | Calves selection criteria | |||||

| 29 | Female selection criteria | |||||

| 30 | Sire selection criteria | |||||

| 31 | Crossbred system | |||||

| 32 | Evaluation in bulls | |||||

| 33 | Semen evaluation | |||||

| 34 | Female evaluation | |||||

| 35 | Oestrus detection | |||||

| 36 | Pregnancy Diagnosis | |||||

| 37 | Mating, | |||||

| 38 | Breeding policy | |||||

| 39 | Health planning | |||||

| 40 | Vaccination program | |||||

| 41 | Parasite diagnosis | |||||

| 42 | Internal deworming control | |||||

| 43 | External parasite control | |||||

| 44 | Mastitis diagnosis | |||||

| 45 | Sanitary milking program | |||||

Appendix 2. Identification of Process Areas in Dual-Purpose Bovine System

Follow the meaning of the values described below. According to your opinion, select one innovation area for each process area.

| N | Innovations | A1. Management | A2. Feeding | A3. Genetics | A4. Reproduction | A5. Animal Health | 6. Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Animal identification | ||||||

| 2 | Record system | ||||||

| 3 | Breeding management | ||||||

| 4 | Grazing native pasture | ||||||

| 5 | Grazing planting | ||||||

| 6 | Grazing of crop residues | ||||||

| 7 | Milking season | ||||||

| 8 | Type of milking | ||||||

| 9 | Green fodder | ||||||

| 10 | Silage | ||||||

| 11 | Hay making | ||||||

| 12 | Processed feed | ||||||

| 13 | Concentrate making | ||||||

| 14 | Molasses/urea | ||||||

| 15 | Grains and oilseeds | ||||||

| 16 | Multi nutritional blocks processed | ||||||

| 17 | Manufacture of multi nutritional blocks | ||||||

| 18 | Common salt | ||||||

| 19 | Mineral salts | ||||||

| 20 | Mineral blocks | ||||||

| 21 | Vitamin provided | ||||||

| 22 | Agro-industrial by-products | ||||||

| 23 | Using male breeds | ||||||

| 24 | Using male crosses | ||||||

| 25 | Using female breeds | ||||||

| 26 | Using female crosses | ||||||

| 27 | Use of genetically tested bulls | ||||||

| 28 | Calves selection criteria | ||||||

| 29 | Female selection criteria | ||||||

| 30 | Sire selection criteria | ||||||

| 31 | Crossbred system | ||||||

| 32 | Evaluation in bulls | ||||||

| 33 | Semen evaluation | ||||||

| 34 | Female evaluation | ||||||

| 35 | Oestrus detection | ||||||

| 36 | Pregnancy Diagnosis | ||||||

| 37 | Mating, | ||||||

| 38 | Breeding policy | ||||||

| 39 | Health planning | ||||||

| 40 | Vaccination program | ||||||

| 41 | Parasite diagnosis | ||||||

| 42 | Internal deworming control | ||||||

| 43 | External parasite control | ||||||

| 44 | Mastitis diagnosis | ||||||

| 45 | Sanitary milking program |

References

- FAO. Ayudando a Desarrollar una Ganadería Sustentable en Latinoamérica y el Caribe: Lecciones a Partir de Casos Exitosos; Organización de las Naciones Unidas Para la Agricultura y Alimentación: Santiago, Chile; Oficina Regional Para América Latina y el Caribe: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van’t Hooft, K.; Wollen, T. Sustainable Livestock Management for Poverty Alleviation and Food Security; Cab International: London, UK, 2012; pp. 120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Angón, E.; García, A.; Perea, J.; Acero, R.; Toro Mujica, P.; Pacheco, H.; González, A. Eficiencia técnica y viabilidad de los sistemas de pastoreo de vacunos de leche en la Pampa Argentina. Agrociencia 2013, 47, 443–456. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, J.; Ortega-Soto, L.; Urdaneta, F.; Sánchez, E. Relación entre el nivel de tecnología y los índices de productividad en fincas ganaderas de doble propósito localizadas en la Cuenca del Lago de Maracaibo. Rev. Cient. (Maracaibo) 2009, 19, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M. Innovation in Africa: Speech on the conference hosted by Trust Africa, CODESRIA and the United Nations Institute for Economic Development and Planning. 24 August 2010. Available online: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/11281/1/innovation-africa.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2015).

- Adekunle, A.A.; Ayanwale, A.; Fatunbi, A.O.; Olarinde, L.O.; Oladunni, O.; Nokoe, S.; Binam, J.N.; Kamara, A.Y.; Maman, K.N.; Dangbegnon, C.; et al. Unlocking the Potenfial for Integrated Agricultural Research for Development in the Savanna of West Africa; Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA): Accra, Ghana; Available online: http://www.pragati.com (accessed on 14 July 2014).

- Albarrán Portillo, B.; Rebollar Rebollar, S.; García Martínez, A.; Rojo Rubio, R.; Avilés Nova, F.; Arriaga Jordán, C. Socioeconomic and productive characterization of dual purpose farms oriented to milk production in a subtropical region of Mexico. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2015, 47, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukute, M. Development Work Research, 1st ed.; Wageningen Academic Publisher: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Pablos Heredero, C.; López Hermoso, J.J.; Romo Romero, S.M.; Medina Salgado, S. Organización y Transformación de los Sistemas de Información en la Empresa; ESIC: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas Reyes, V.; Baca del Moral, J.; Cervantes Escoto, F.; Espinosa García, J.A.; Aguilar Avila, J.; Loaiza Meza, A. Factores que determinan el uso de innovaciones técnológicas en la ganadería de doble propósito en Sinaloa, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pec. 2013, 4, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- De Pablos-Heredero, C. Cloud computing practices and final performance: The key role of relational coordination. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2015, 5, 234–256. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, J.; García, A.; Toro-Mujica, P.; Angón, E.; Perea, J.; Morantes, M.; Dios-Palomares, R. Caracterización técnica, social y comercial de las explotaciones ovinas manchegas, centro-sur de España. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2014, 3, 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gal, P.Y.; Dugué, P.; Faure, G.; Novak, S. How does research address the design of innovative agricultural production systems at the farm level? A review. Agric. Syst. 2011, 104, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, J.; Torres, Y.; de Pablos-Heredero, C.; Espinoza, J.A.; Rivas, J.; Garcia, A. Identification of technological areas for dual purpose cattle in Mexico and Ecuador. In Proceedings of the 66th Annual Meeting of the European Federation of Animal Science EAAP, Warsaw, Poland, 31 August–4 September 2015.

- Torres, Y.; Rivas, J.; de Pablos Herederos, C.; Perea, J.; Toro Mújica, P.; Angón, E.; García, A. Identificación e implementación de paquetes tecnológicos en ganadería vacuna de doble propósito. Caso Manabí-Ecuador. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2014, 5, 393–407. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa García, J.A.; Quiroz, J.; Moctezuma, G.; Oliva, J.; Granados, L.; Berumen, A.C. Technological Prospection and Strategies for Innovation in Production of Sheep in Tabasco, México. Rev. Cient. Fac. Cienc. Vet. 2015, 25, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Aldana, U.; Foltz, J.D.; Barham, B.L.; Useche, P. Sequential adoption of package technologies the dynamics of stacked trait corn adoption. Am. J. Agrc. Econ. 2010, 93, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentes, P.; Peters, M.; Holmann, F. Regionalization of climatic factors and income indicadors for milk production in Honduras. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosting, S.; Udo, H.; Viets, T. Development of livestock production in the tropics: Farm and farmers’ perspectives. Animal 2014, 8, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. World Mapping of Animal Feeding Systems in the Dairy Sector; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Noltze, M.; Schwarze, A.; Qaim, M. Understanding the adoption of system technologies in smallholder agriculture: The system of rice intensification (SRI) in Timor Leste. Agric. Syst. 2012, 108, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, A.; Albarrán-Portillo, B.; Avilés-Novoa, F. Dinámicas y tendencias de la ganadería de doble propósito en el sur del Estado de México. Agrociencia 2015, 49, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Dubeuf, J.P. The social and environmental challenges faced by goat and small livestock local activities: Present contribution of research-development and stakes for the future. Small Rumi. Res. 2014, 98, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro Mujica, P.; García, A.; Gómez Castro, G.; Acero, R.; Perea, J.; Rodríguez Estévez, V.; Aguilar, C.; Vera, R. Technical efficiency and viability of organic dairy sheep farming systems in a traditional area for sheep production in Spain. Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 100, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros, V.; Díaz, P.; Vilaboa, J.; Martínez, J.P.; Torres, G. Caracterización por grupos tecnológicos de los hatos ganaderos doble propósito en el municipio de las Choapas, Veracruz, México. Rev. Cient. Fac. Cienc. Vet. 2011, 21, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, H.; Dehninet, G.; Kelay, B. Dairy technology adoTAion in smallholder farms in “Dejen” district, Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2010, 42, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas Reyes, V.; Espejel García, A.; Nieto, C.A.R.; Loaiza, A.; Meza, A.B.R.; Montes, M.S. Factors that determine the level of human capital of the livestock extension agent in Mexico. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. 2015, 3, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, P.; Oros, V.; Vilaboa, J.; Martínez, J.P.; Torres, G. Dinámica del desarrollo de la ganadería doble propósito en las Choapas, Veracruz. México. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2011, 14, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bartl, K.; Mayer, A.C.; Gómez, C.A.; Muñoz, E.; Hess, H.D.; Hollmann, F. Economic evaluation of current and alternative dual—Purpose cattle systems for smallholder farms in the central Peruvian highlands. Agric. Syst. 2009, 101, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Estado Mundial de la Agricultura y la Alimentación 2010–2011. Las Mujeres en la Agricultura. Cerrar la Brecha de Género en Aras del Desarrollo; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Ganadería Mundial 2011—La Ganaderia en la Seguridad Alimentaria; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y Agricultura FAO: Roma, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Y.; García, A.; Rivas, J.; Perea, J.; Angón, E.; de Pablos-Heredero, C. Socioeconomic and Productive Characterization of Dual-Purpose Farms Oriented to Milk Production in a Tropical Region of Ecuador. The Case of the Province of Manabí. Rev. Cient. Fac. Cienc. Vet. 2015, 25, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Gouttenoire, L.; Cournut, S.; Ingrand, S. Participatory modelling with farmer groups to help them redesign their livestock farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryschawy, J.; Joamnon, A.; Choisis, J.P.; Gibón, A.; le Gal, P.Y. Participative assessment of innovative technical scenarios for enhancing sustainability of French mixed crop-livestock farms. Agric. Syst. 2014, 129, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.; Cassidy, E.; Gerber, J.; Johnston, M.; Zaks, D. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel-Quintos, J.; Espinosa, J.; de Pablos, C.; Angón, E.; Perea, J.; Rivas, J.; García, A. Indicadores de desarrollo humano en el sistema bovino de doble propósito en el trópico mexicano. Rev. Cient. Univ. Téc. Estatal Quevedo 2014, 7, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, J.; Perea, J.; Angón, E.; Barba, C.; Morantes, M.; Dios Palomares, R.; García, A. Diversity in the dry land mixed system and viability of dairy sheep farming. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 14, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, B.U.; Amaro, G.R.; Bueno, D.H.M.; Chagoya, F.J.L.; Koppel, R.E.T.; Ortiz, O.G.A.; Vázquez, G.R. Manual para la Formación de Capacitadores Modelo GGAVATT. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería. Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación (SAGARPA); Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP). Centro de Investigación Regional del Centro (CIRCE): Zacatepec, México, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-González, J.M.; Leos, J.A.; Sagarnaga, L.M.; Zavala, M.J. Adopción de tecnologías por productores beneficiarios del programa de estímulos a la productividad ganadera (PROGAN) en México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2013, 4, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Toro Mujica, P.; García, A.; Gómez Castro, G.; Perea, J.; Rodríguez Estévez, V.; Angón, E. Organic dairy sheep farms in south-central Spain: Typologies according to livestock management and economic variables. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 104, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morantes, M.; Dios Palomares, R.; Peña, M.E.; Rivas, J.; Angón, E.; Perea, J.; García, A. The effect of farmer characteristics into management functions: A study in dairy sheep systems in the Castilla La Mancha. Spain. Rev. Cient. Fac. Cienc. Vet. 2014, 24, 224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Valdovinos, M.E.; Espinosa, J.A.; Velez, A. Inovación y eficiencia de unidades bovinas de doble propósito en Veracruz. Rev. Mex. Agro. 2015, 19, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Vayssisières, J.; Vigne, M.; Alary, V.; Lecomte, P. Integrated participatory modeling of actual farms to support policy making of sustainable intensification. Agric. Syst. 2011, 104, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, C.; León, H.; Pérez, E.; Tole, L.; Fawcett, R.H.; Herrero, M. Using farmer decision-making profiles and managerial capacity as predictors of farm management and performance in Costa Rican dairy farms. Agric. Syst. 2006, 88, 395–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, J.E.O.; Marshall, K.; Notembaert, A.; Ojango, J.M.K.; Okeyo, A.M. Pro-poor animal improvement and breeding. What can science do? Livest. Sci. 2011, 136, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F. Beyond the bounded instrumentality in current corporate sustainability research: Toward an inclusive notion of profitability. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; de Bruijn, E.J.; Fisscher, O.A.M.; Steenhuis, H. Achieving Sustainability Three dimensionally. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation and Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, 21–24 September 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).