Association Between TikTok Use and Anxiety, Depression, and Sleepiness Among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Is there an association between TikTok use and anxiety in adolescents? We expected a positive association between variables.

- Is there an association between TikTok use and depression in adolescents? We expected a positive association between variables.

- Is there an association between TikTok use and sleepiness in adolescents? We expected a positive association between variables.

- Are there possible differences between girls and boys regarding the association between TikTok use, anxiety, depression, and sleepiness in adolescents? We expected differences between the two genders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Ethical Issues

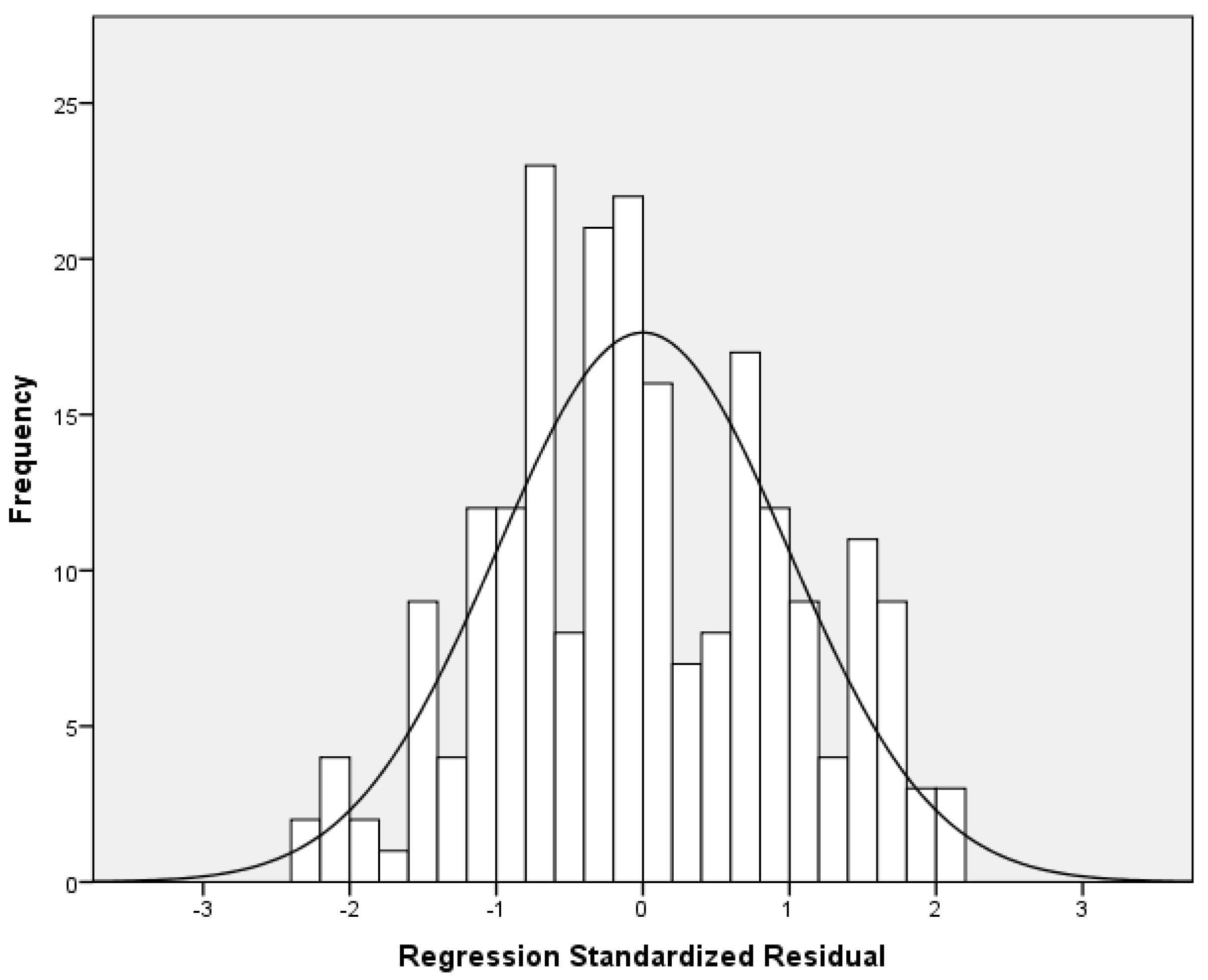

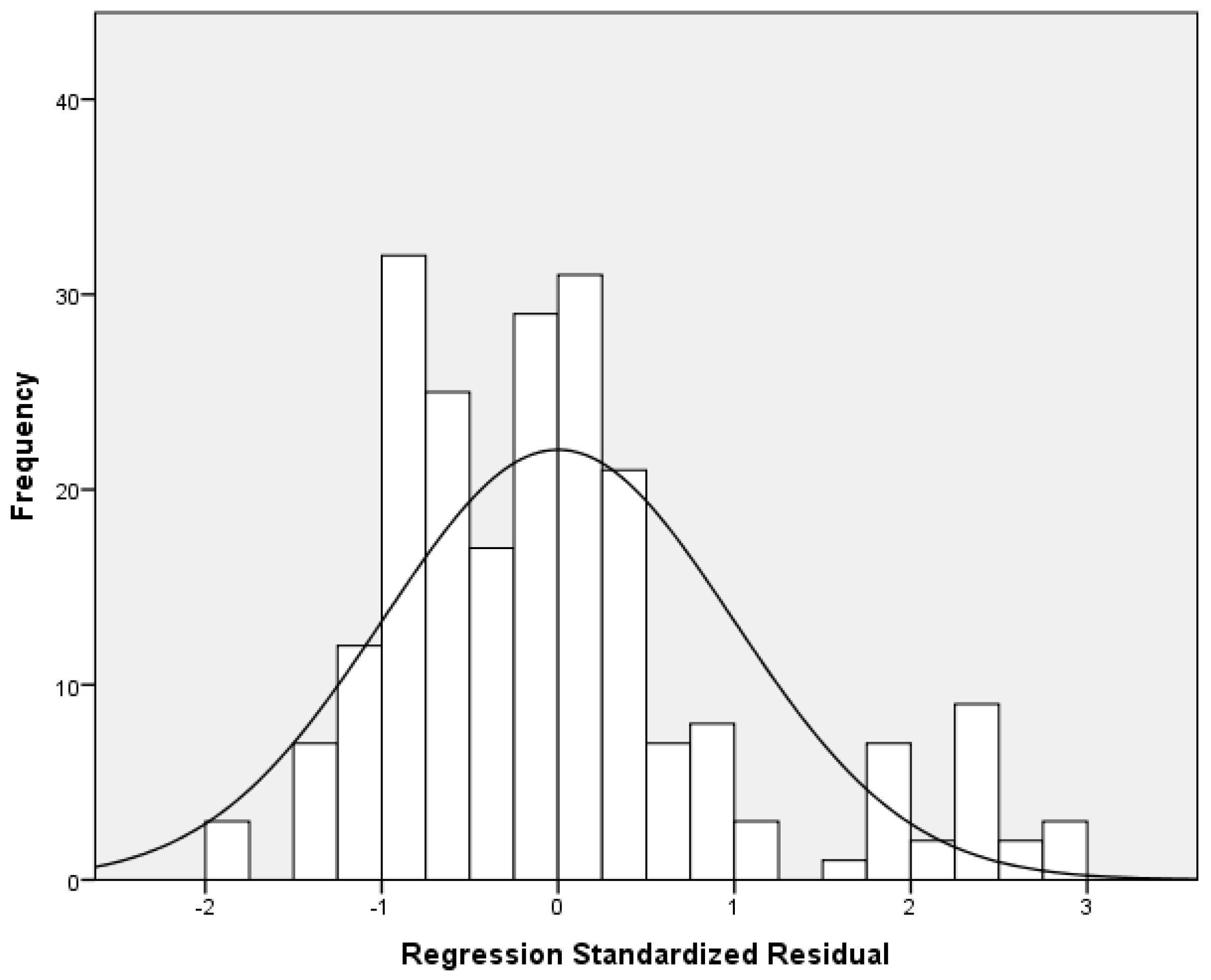

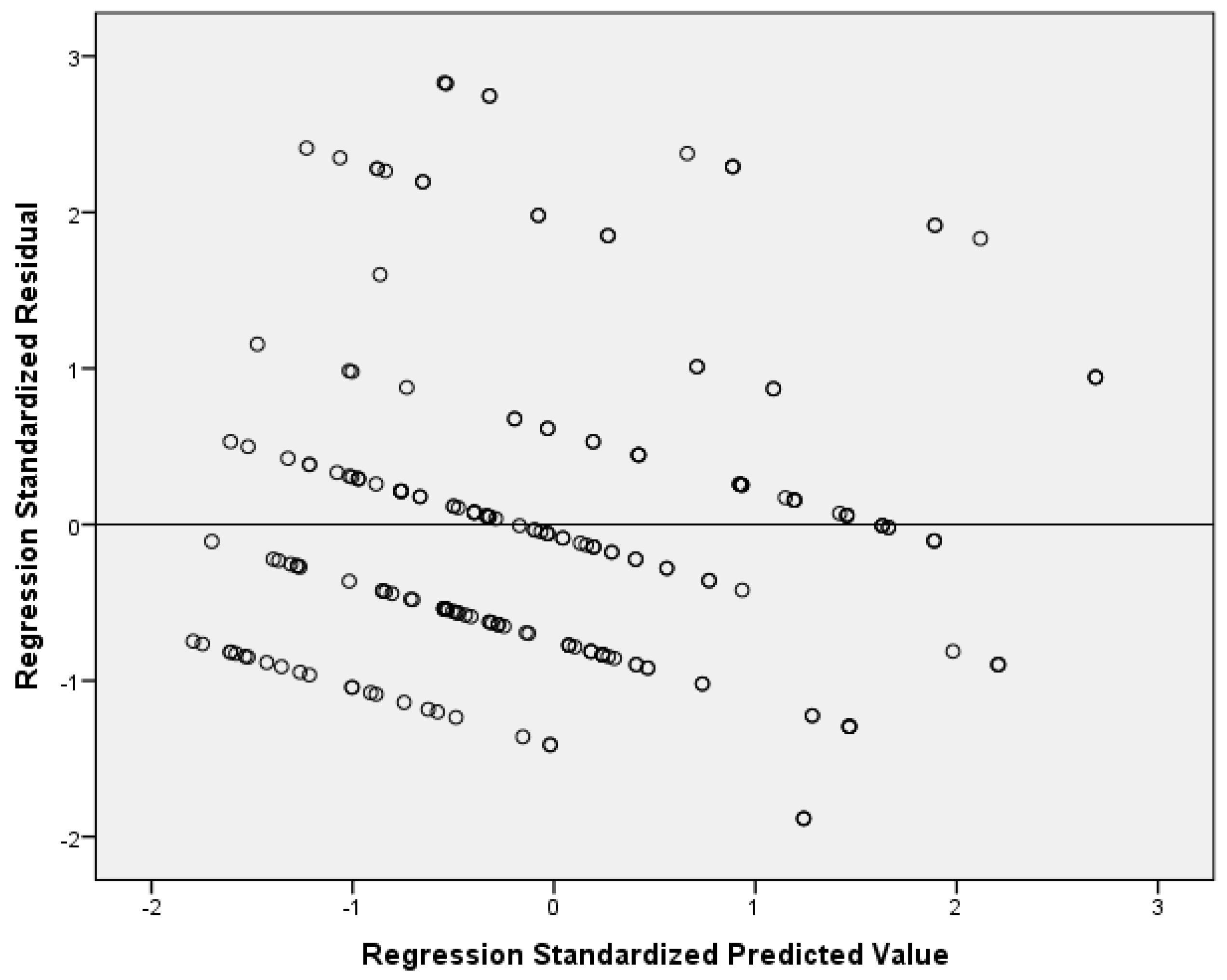

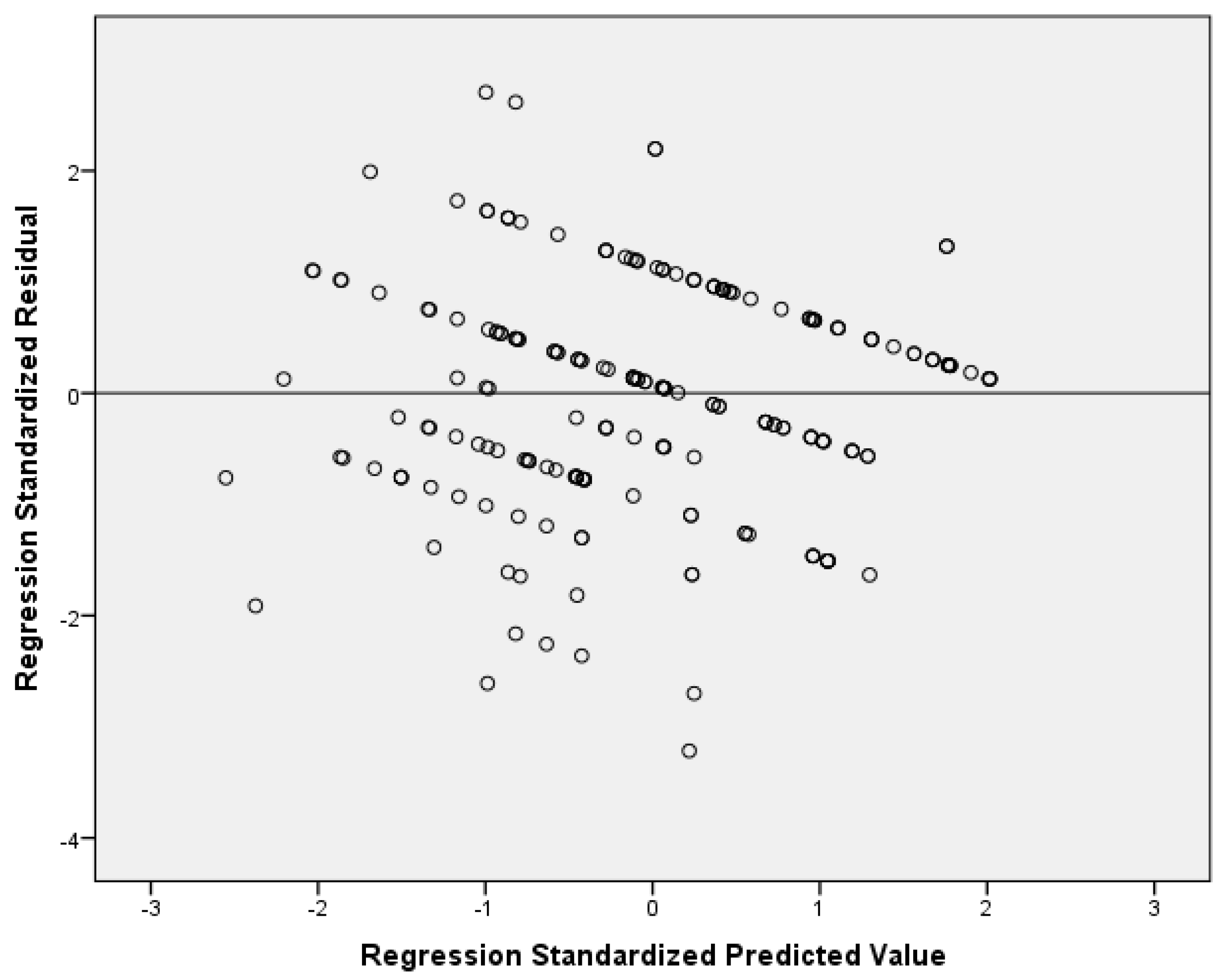

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. TikTok Use

3.3. Anxiety and Depression

3.4. Association Between TikTok Use and Anxiety

3.5. Association Between TikTok Use and Depression

3.6. Association Between TikTok Use and Sleepiness

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Social Media & User-Generated Content. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Anderson, K.E. Getting Acquainted with Social Networks and Apps: It Is Time to Talk about TikTok. Libr. Hi Tech News 2020, 37, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, B.; Garimella, A.; Pillarisetti, L.; Charlly, N.; Sullivan, K.; Moreno, M.A. Associations Between Social Media Use and Anxiety Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2025, 76, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanko, D. The Health Effects of Video Games in Children and Adolescents. Pediatr. Rev. 2023, 44, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granic, I.; Lobel, A.; Engels, R.C.M.E. The Benefits of Playing Video Games. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lager, A. Health Effects of Video and Computer Game Playing: A Systematic Review; Swedish National Institute of Public Health: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005; ISBN 978-91-7257-519-6. [Google Scholar]

- D’Errico, F.; Cicirelli, P.G.; Papapicco, C.; Scardigno, R. Scare-Away Risks: The Effects of a Serious Game on Adolescents’ Awareness of Health and Security Risks in an Italian Sample. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2022, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeyer, T. Prosocial Modeling: Person Role Models and the Media. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A Systematic Review: The Influence of Social Media on Depression, Anxiety and Psychological Distress in Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, N.; Young, P.; Yousuf, S. Exploring the Relationship Between Social Media Use and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Narrative Review. Cyberpsychol Behav. Soc. Netw. 2024, 27, 771–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.; Lei, J.; He, R.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, H. TikTok Use and Psychosocial Factors among Adolescents: Comparisons of Non-Users, Moderate Users, and Addictive Users. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 325, 115247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzler, A.L.; Hughes, J.L.; Johnston, M.; Alderson, J.E. Which Social Media Platforms Matter and for Whom? Examining Moderators of Links between Adolescents’ Social Media Use and Depressive Symptoms. J. Adolesc. 2023, 95, 1725–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, P.; Dong, X. Research on Adolescents Regarding the Indirect Effect of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress between TikTok Use Disorder and Memory Loss. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilic-Zivojinovic, J.; Mitic, T.; Sreckovic, M.; Backovic, D.; Soldatovic, I. The Relationship between Internet Use and Depressive Symptoms among High School Students. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2023, 151, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The Smartphone Addiction Scale: Development and Validation of a Short Version for Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feijoo, B.; Cambronero-Saiz, B.; Miguel-San-Emeterio, B. Body Perception and Frequency of Exposure to Advertising on Social Networks among Adolescents. Prof. De La Inf. 2023, 32, e320318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, L.; Lo Coco, G.; Teti, A.; Bonfanti, R.C.; Salerno, L. Time Spent on Mobile Apps Matters: A Latent Class Analysis of Patterns of Smartphone Use among Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; Chen, S.; Jiménez-López, E.; Abellán-Huerta, J.; Herrera-Gutiérrez, E.; Royo, J.M.P.; Mesas, A.E.; Tárraga-López, P.J. Are the Use and Addiction to Social Networks Associated with Disordered Eating Among Adolescents? Findings from the EHDLA Study. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2024, 22, 3775–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, J.M.; Patino Alonso, C.; Pessoa, T.; Martín-Lucas, J. Identity Profile of Young People Experiencing a Sense of Risk on the Internet: A Data Mining Application of Decision Tree with CHAID Algorithm. Comput. Educ. 2023, 197, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruccoli, J.; De Rosa, M.; Chiasso, L.; Perrone, A.; Parmeggiani, A. The Use of TikTok among Children and Adolescents with Eating Disorders: Experience in a Third-Level Public Italian Center during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Musetti, A.; Omar, B. Flow Experience Is a Key Factor in the Likelihood of Adolescents’ Problematic TikTok Use: The Moderating Role of Active Parental Mediation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Omar, B.; Musetti, A. The Addiction Behavior of Short-Form Video App TikTok: The Information Quality and System Quality Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 932805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagrera, C.E.; Magner, J.; Temple, J.; Lawrence, R.; Magner, T.J.; Avila-Quintero, V.J.; McPherson, P.; Alderman, L.L.; Bhuiyan, M.A.N.; Patterson, J.C.; et al. Social Media Use and Body Image Issues among Adolescents in a Vulnerable Louisiana Community. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1001336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarman, A.; Tuncay, S. The Relationship of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok and WhatsApp/Telegram with Loneliness and Anger of Adolescents Living in Turkey: A Structural Equality Model. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2023, 72, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.; Iftikhar, A.; Meer, A. Intervening Effects of Academic Performance between TikTok Obsession and Psychological Wellbeing Challenges in University Students. Online Media Soc. 2022, 3, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Adnan, H.; Sarmiti, N. The Relationship Between Anxiety and TikTok Addiction Among University Students in China: Mediated by Escapism and Use Intensity. Int. J. Media Inf. Lit. 2023, 8, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Chen, J.; Huang, S.; Montag, C.; Elhai, J.D. Depression and Social Anxiety in Relation to Problematic TikTok Use Severity: The Mediating Role of Boredom Proneness and Distress Intolerance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 145, 107751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa-Blanco, M.; García, Y.R.; Landa-Blanco, A.L.; Cortés-Ramos, A.; Paz-Maldonado, E. Social Media Addiction Relationship with Academic Engagement in University Students: The Mediator Role of Self-Esteem, Depression, and Anxiety. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikse, C.; Limniou, M. The Use of Instagram and TikTok in Relation to Problematic Use and Well-Being. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2024, 9, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.M.; Cincio, A. Procrastination Mediates the Relationship between Problematic TikTok Use and Depression among Young Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Lewin, K.M.; Meshi, D. Problematic Use of Five Different Social Networking Sites Is Associated with Depressive Symptoms and Loneliness. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 20891–20898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Garni, A.M.; Alamri, H.S.; Asiri, W.M.A.; Abudasser, A.M.; Alawashiz, A.S.; Badawi, F.A.; Alqahtani, G.A.; Ali Alnasser, S.S.; Assiri, A.M.; Alshahrani, K.T.S.; et al. Social Media Use and Sleep Quality Among Secondary School Students in Aseer Region: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 3093–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, M.R.; Hogg, R.C. #ForYou? The Impact of pro-Ana TikTok Content on Body Image Dissatisfaction and Internalisation of Societal Beauty Standards. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Katsiroumpa, Z.; Mangoulia, P.; Gallos, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Koukia, E. Impact of Problematic TikTok Use on Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Åkerstedt, T.; Gillberg, M. Subjective and Objective Sleepiness in the Active Individual. Int. J. Neurosci. 1990, 52, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoddes, E.; Dement, W.; Zarcone, V. The Development and Use of the Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS). Psychophysiology 1972, 9, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Moisoglou, I.; Konstantakopoulou, O. The TikTok Addiction Scale: Development and Validation. AIMS Public. Health 2024, 11, 1172–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Moisoglou, I.; Konstantakopoulou, O. Determining an Optimal Cut-off Point for TikTok Addiction Using the TikTok Addiction Scale. Arch. Hell. Med. 2025. under press. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Lowe, B. An Ultra-Brief Screening Scale for Anxiety and Depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karekla, M.; Pilipenko, N.; Feldman, J. Patient Health Questionnaire: Greek Language Validation and Subscale Factor Structure. Compr. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. Linear Models, Problems. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 515–522. ISBN 978-0-12-369398-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H. Multicollinearity and Misleading Statistical Results. Korean J. Anesth. 2019, 72, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N. Gender Differences in Associations between Digital Media Use and Psychological Well-being: Evidence from Three Large Datasets. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kircaburun, K.; Alhabash, S.; Tosuntaş, Ş.B.; Griffiths, M.D. Uses and Gratifications of Problematic Social Media Use Among University Students: A Simultaneous Examination of the Big Five of Personality Traits, Social Media Platforms, and Social Media Use Motives. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, P.S.; Moody, J. Suicide and Friendships Among American Adolescents. Am. J. Public. Health 2004, 94, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flook, L. Gender Differences in Adolescents’ Daily Interpersonal Events and Well-Being: Daily Events and Well-Being. Child. Dev. 2011, 82, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFontana, K.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N. Developmental Changes in the Priority of Perceived Status in Childhood and Adolescence. Soc. Dev. 2010, 19, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, M.; Wickham, R.E.; Acitelli, L.K. Seeing Everyone Else’s Highlight Reels: How Facebook Usage Is Linked to Depressive Symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 33, 701–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Vendemia, M.A. Selective Self-Presentation and Social Comparison Through Photographs on Social Networking Sites. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, J.V.; Mills, J.S. The Effects of Active Social Media Engagement with Peers on Body Image in Young Women. Body Image 2019, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Bae, S.C.; Bae, S.; Kim, H.; Sim, M.; Lyoo, I.K.; Cho, S.C. Depression and Internet Addiction in Adolescents. Psychopathology 2007, 40, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBourgeois, M.K.; Hale, L.; Chang, A.-M.; Akacem, L.D.; Montgomery-Downs, H.E.; Buxton, O.M. Digital Media and Sleep in Childhood and Adolescence. Pediatrics 2017, 140, S92–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, U.; Khan, M.K.; Albashari, M. Link between Excessive Social Media Use and Psychiatric Disorders. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Asam, A.; Samara, M.; Terry, P. Problematic Internet Use and Mental Health among British Children and Adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2019, 90, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuss, D.; Griffiths, M.; Karila, L.; Billieux, J. Internet Addiction: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Research for the Last Decade. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4026–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Huang, L.; Yang, F. Social Anxiety and Problematic Social Media Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Addict. Behav. 2024, 153, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.-T.G.; Edge, N. “They Are Happier and Having Better Lives than I Am”: The Impact of Using Facebook on Perceptions of Others’ Lives. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E.; Verduyn, P.; Demiralp, E.; Park, J.; Lee, D.S.; Lin, N.; Shablack, H.; Jonides, J.; Ybarra, O. Facebook Use Predicts Declines in Subjective Well-Being in Young Adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagioglou, C.; Greitemeyer, T. Facebook’s Emotional Consequences: Why Facebook Causes a Decrease in Mood and Why People Still Use It. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Whaite, E.O.; Lin, L.Y.; Rosen, D.; Colditz, J.B.; Radovic, A.; Miller, E. Social Media Use and Perceived Social Isolation Among Young Adults in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.C.; Ferrucci, P.; Duffy, M. Facebook Use, Envy, and Depression among College Students: Is Facebooking Depressing? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.H.; Kim, S.H. Comprehending Envy. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.J. Issues for DSM-V: Internet Addiction. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, C.M.; Gore, H. The Relationship between Excessive Internet Use and Depression: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 1,319 Young People and Adults. Psychopathology 2010, 43, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, E.P.; Gray, J. Facebook Photo Activity Associated with Body Image Disturbance in Adolescent Girls. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Yang, F.; Haigh, M.M. Let Me Take a Selfie: Exploring the Psychological Effects of Posting and Viewing Selfies and Groupies on Social Media. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, G.S.; Clarke-Pearson, K. Council on Communications and Media The Impact of Social Media on Children, Adolescents, and Families. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garett, R.; Liu, S.; Young, S.D. The Relationship between Social Media Use and Sleep Quality among Undergraduate Students. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautsch, L.A.; Lund, L.; Andersen, M.M.; Jennum, P.J.; Folker, A.P.; Andersen, S. Digital Media Use and Sleep in Late Adolescence and Young Adulthood: A Systematic Review. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2023, 68, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Agostiniani, R.; Barni, S.; Russo, R.; Scarpato, E.; Di Mauro, A.; Di Stefano, A.V.; Caruso, C.; Corsello, G.; et al. The Use of Social Media in Children and Adolescents: Scoping Review on the Potential Risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, G.; Bozzola, E.; Ferrara, P.; Zamperini, N.; Marino, F.; Caruso, C.; Antilici, L.; Villani, A. Children and Adolescent’s Perception of Media Device Use Consequences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exelmans, L.; Van Den Bulck, J. Bedtime Mobile Phone Use and Sleep in Adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 148, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassiakos, Y.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C.; Hill, D.; Ameenuddin, N.; Hutchinson, J.; Levine, A.; Boyd, R.; et al. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, C. Current Perspectives: The Impact of Cyberbullying on Adolescent Health. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2014, 5, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skilbred-Fjeld, S.; Reme, S.E.; Mossige, S. Cyberbullying Involvement and Mental Health Problems among Late Adolescents. Cyberpsychology 2020, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, R.; Smith, P.K.; Frisén, A. The Nature of Cyberbullying, and Strategies for Prevention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Yang, H.; Elhai, J.D. On the Psychology of TikTok Use: A First Glimpse From Empirical Findings. Front. Public. Health 2021, 9, 641673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, L.; Dang, D.; Barker, C.J.; Heath, M.; Mesiya, S.; Tienabeso, T.; Watson, K. Evening Wear of Blue-Blocking Glasses for Sleep and Mood Disorders: A Systematic Review. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessel, L.; Siganos, G.; Jørgensen, T.; Larsen, M. Sleep Disturbances Are Related to Decreased Transmission of Blue Light to the Retina Caused by Lens Yellowing. Sleep 2011, 34, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, L.; Guan, S. Screen Time and Sleep among School-Aged Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 21, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, I.; D’Errico, F. The Mental Ingredients of Bitterness. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2010, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. Reliability and Factor Analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1992, 15, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Pereira, A.; Vagos, P.; Nóbrega, C.; Gonçalves, J.; Afonso, B. Effectiveness of Mobile App-Based Psychological Interventions for College Students: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Minimum Value | Maximum Value | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TikTok Addiction Scale | 1.07 | 4.07 | 2.48 | 0.69 | 2.47 | 0.26 | −0.55 |

| Salience | 1.00 | 4.50 | 1.99 | 0.85 | 2.00 | 0.67 | 0.06 |

| Mood modification | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.64 | 0.89 | 3.50 | −0.77 | 0.16 |

| Tolerance | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.12 | 0.99 | 3.00 | −0.03 | −0.37 |

| Withdrawal symptoms | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.45 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 0.15 |

| Conflict | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.55 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 0.57 | −0.36 |

| Relapse | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.83 | 0.96 | 1.50 | 0.91 | −0.01 |

| Independent Variables | Univariate Models | Multivariable Model a,b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Coefficient Beta | 95% CI for Beta | p-Value | Adjusted Coefficient Beta | 95% CI for Beta | p-Value | VIF | |

| Full sample b | |||||||

| Mood modification | 0.476 | 0.224 to 0.728 | <0.001 | 0.404 | 0.115 to 0.693 | 0.006 | 1.301 |

| Conflict | 0.266 | 0.034 to 0.497 | 0.025 | 0.098 | −0.168 to 0.365 | 0.467 | 1.366 |

| sRelapse | 0.280 | 0.040 to 0.520 | 0.023 | 0.066 | −0.220 to 0.351 | 0.651 | 1.450 |

| Boys (n = 41) c | |||||||

| Mood modification | 1.130 | 0.418 to 1.842 | 0.003 | 0.760 | 0.121 to 1.399 | 0.021 | 1.343 |

| Conflict | 1.392 | 0.926 to 1.858 | <0.001 | 1.236 | 0.763 to 1.710 | <0.001 | 1.126 |

| Relapse | 0.243 | −0.524 to 1.010 | 0.525 | −0.063 | −0.660 to 0.533 | 0.831 | 1.264 |

| Girls (n = 178) d | |||||||

| Mood modification | 0.365 | 0.093 to 0.638 | 0.009 | 0.338 | 0.031 to 0.645 | 0.031 | 1.283 |

| Conflict | 0.019 | −0.235 to 0.273 | 0.883 | −0.273 | −0.581 to 0.034 | 0.081 | 1.539 |

| Relapse | 0.283 | 0.031 to 0.534 | 0.028 | 0.304 | −0.013 to 0.621 | 0.060 | 1.006 |

| Independent Variables | Univariate Models | Multivariable Model a,b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Coefficient Beta | 95% CI for Beta | p-Value | Adjusted Coefficient Beta | 95% CI for Beta | p-Value | VIF | |

| Full sample b | |||||||

| Mood modification | 0.296 | 0.065 to 0.527 | 0.012 | 0.051 | −0.200 to 0.303 | 0.688 | 1.301 |

| Conflict | 0.542 | 0.344 to 0.740 | <0.001 | 0.472 | 0.239 to 0.704 | <0.001 | 1.366 |

| Relapse | 0.374 | 0.161 to 0.588 | 0.001 | 0.117 | −0.132 to 0.366 | 0.355 | 1.450 |

| Boys (n = 41) c | |||||||

| Mood modification | 0.387 | −0.358 to 1.131 | 0.300 | −0.245 | −0.979 to 0.489 | 0.503 | 1.343 |

| Conflict | 1.011 | 0.495 to 1.527 | <0.001 | 1.076 | 0.532 to 1.620 | <0.001 | 1.126 |

| Relapse | 0.538 | −0.168 to 1.244 | 0.131 | 0.650 | −0.035 to 1.336 | 0.062 | 1.264 |

| Girls (n = 178) d | |||||||

| Mood modification | 0.295 | 0.052 to 0.538 | 0.018 | 0.101 | −0.166 to 0.369 | 0.456 | 1.283 |

| Conflict | 0.456 | 0.241 to 0.672 | <0.001 | 0.361 | 0.093 to 0.629 | 0.009 | 1.539 |

| Relapse | 0.351 | 0.130 to 0.572 | 0.002 | 0.102 | −0.174 to 0.379 | 0.466 | 1.620 |

| Independent Variables | Univariate Models | Multivariable Model a,b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Coefficient Beta | 95% CI for Beta | p-Value | Adjusted Coefficient Beta | 95% CI for Beta | p-Value | VIF | |

| Full sample b | |||||||

| Mood modification | 0.818 | 0.526 to 1.111 | <0.001 | 0.655 | 0.336 to 0.975 | <0.001 | 1.301 |

| Conflict | 0.789 | 0.529 to 1.049 | <0.001 | 0.674 | 0.379 to 0.969 | <0.001 | 1.366 |

| Relapse | 0.386 | 0.098 to 0.673 | 0.009 | −0.217 | −0.533 to 0.098 | 0.176 | 1.450 |

| Boys (n = 41) c | |||||||

| Mood modification | 0.981 | 0.254 to 1.708 | 0.009 | 1.030 | 0.246 to 1.813 | 0.011 | 1.343 |

| Conflict | 0.754 | 0.160 to 1.348 | 0.014 | 0.450 | −0.130 to 1.031 | 0.124 | 1.126 |

| Relapse | −0.117 | −0.880 to 0.646 | 0.759 | −0.621 | −1.352 to 0.111 | 0.094 | 1.264 |

| Girls (n = 178) d | |||||||

| Mood modification | 0.790 | 0.462 to 1.118 | <0.001 | 0.610 | 0.255 to 0.965 | 0.001 | 1.283 |

| Conflict | 0.794 | 0.498 to 1.089 | <0.001 | 0.675 | 0.319 to 1.031 | <0.001 | 1.539 |

| Relapse | 0.457 | 0.145 to 0.770 | 0.004 | −0.178 | −0.545 to 0.189 | 0.339 | 1.620 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bilali, A.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Koutelekos, I.; Dafogianni, C.; Gallos, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Galanis, P. Association Between TikTok Use and Anxiety, Depression, and Sleepiness Among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greece. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020034

Bilali A, Katsiroumpa A, Koutelekos I, Dafogianni C, Gallos P, Moisoglou I, Galanis P. Association Between TikTok Use and Anxiety, Depression, and Sleepiness Among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greece. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleBilali, Angeliki, Aglaia Katsiroumpa, Ioannis Koutelekos, Chrysoula Dafogianni, Parisis Gallos, Ioannis Moisoglou, and Petros Galanis. 2025. "Association Between TikTok Use and Anxiety, Depression, and Sleepiness Among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greece" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020034

APA StyleBilali, A., Katsiroumpa, A., Koutelekos, I., Dafogianni, C., Gallos, P., Moisoglou, I., & Galanis, P. (2025). Association Between TikTok Use and Anxiety, Depression, and Sleepiness Among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greece. Pediatric Reports, 17(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020034