Propensity Score Matching: Identifying Opportunities for Future Use in Nursing Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Using synthetic knowledge synthesis, we identified study themes by analyzing publications describing PSM use in nursing published in the period 2020–2024 from the Web of Science bibliographic database, using the search string “propensity score matching” limited to the research area of nursing. The study period was limited to the recent five years to analyze state-of-the-art research and trends only. No additional inclusion/exclusion criteria were used.

- Using synthetic knowledge synthesis, we identified the most popular themes for observational, retrospective, and other quasi-experimental studies in nursing using the same study period and bibliographic database as in Step 1. The search string was observational or retrospective or “quasi?experimental” limited to research area Nursing. No additional inclusion/exclusion criteria were used.

- Comparing the themes identified in Step 1 and Step 2 and using themes emerging just in Step 2 as keywords, we searched for influential articles in the Web of Science and Scopus databases, where PMS has already been successfully used in medical applications. The cases presented in these articles were finally identified as new opportunities for PSM use in nursing.

- Develop a comprehensive search strategy to compile a relevant corpus of publications that addresses the research objectives through a knowledge synthesis process.

- Select Author Keywords as units of information for content analysis, as they precisely reflect the intended focus of the research that authors aim to share with the academic community, while maintaining a balance between structured terminology and author-driven expression.

- Perform a bibliometric mapping of author’s keywords into a clustered bibliometric map using VOSViewer [34].

- Analyze the links and proximity between author keywords in individual clusters to form categories.

- Condense categories into themes.

3. Results and Discussion

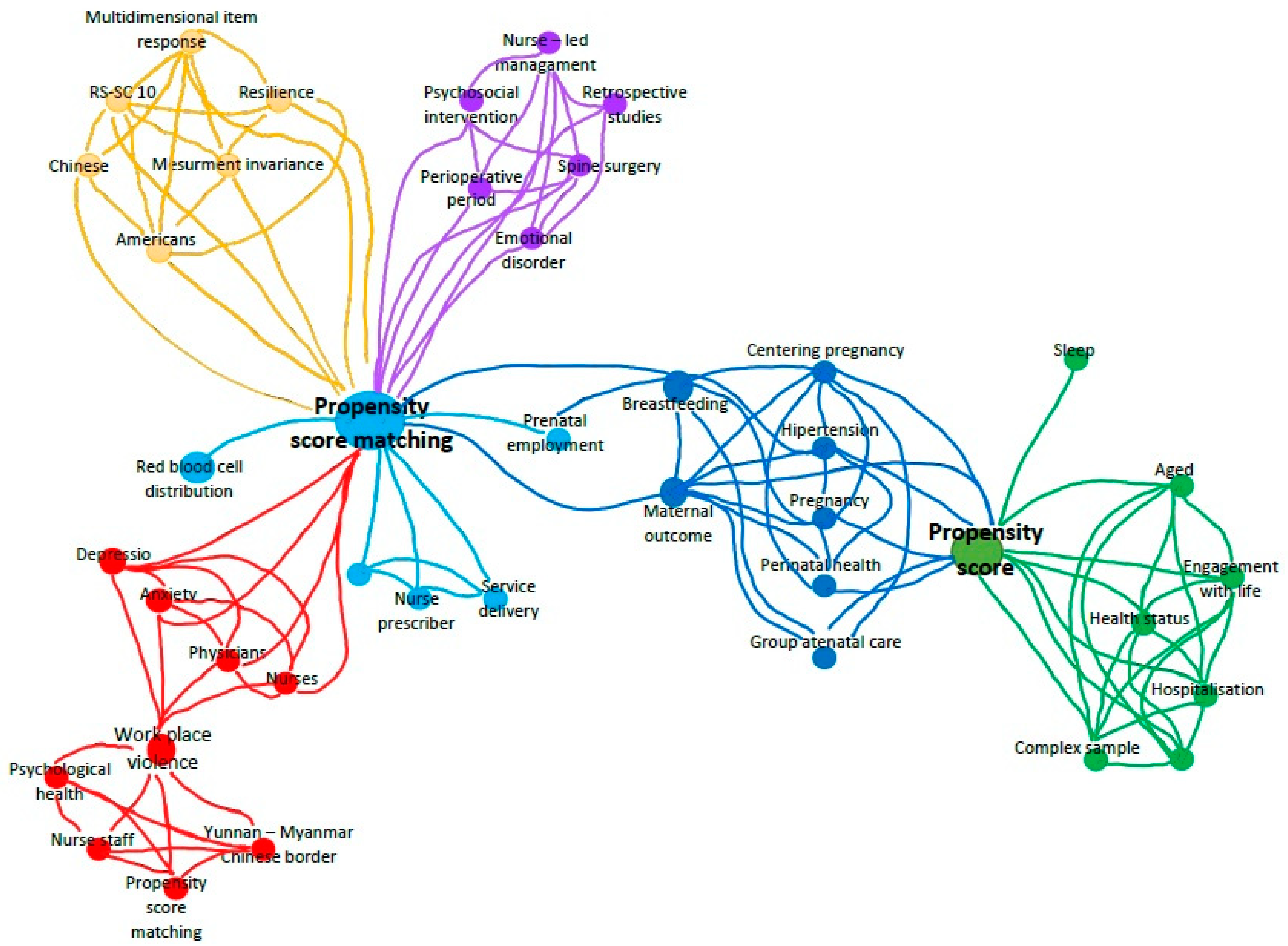

3.1. Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis of Nursing PSM Studies

- Red cluster: Psychological health (anxiety and depression) of nursing staff after workplace violence. PSM and regression analysis were used to compare depression and anxiety symptoms in physicians and nurses who had or had not experienced workplace violence [35] or whether workplace violence affects psychological health in general [22].

- Light blue cluster: Nurse-led management [36].

- Violet cluster: Nurse-led management. PMS was used to compare groups of patients who received nurse-led multidisciplinary psychological management and who did not [36] to compare anesthesia-related outcomes between patients monitored by newly recruited nurse anesthetists and those monitored by newly recruited anesthesiologists [39].

- Green cluster: Successful aging. PSM was used to assess the effect of hospitalization on successful aging [42].

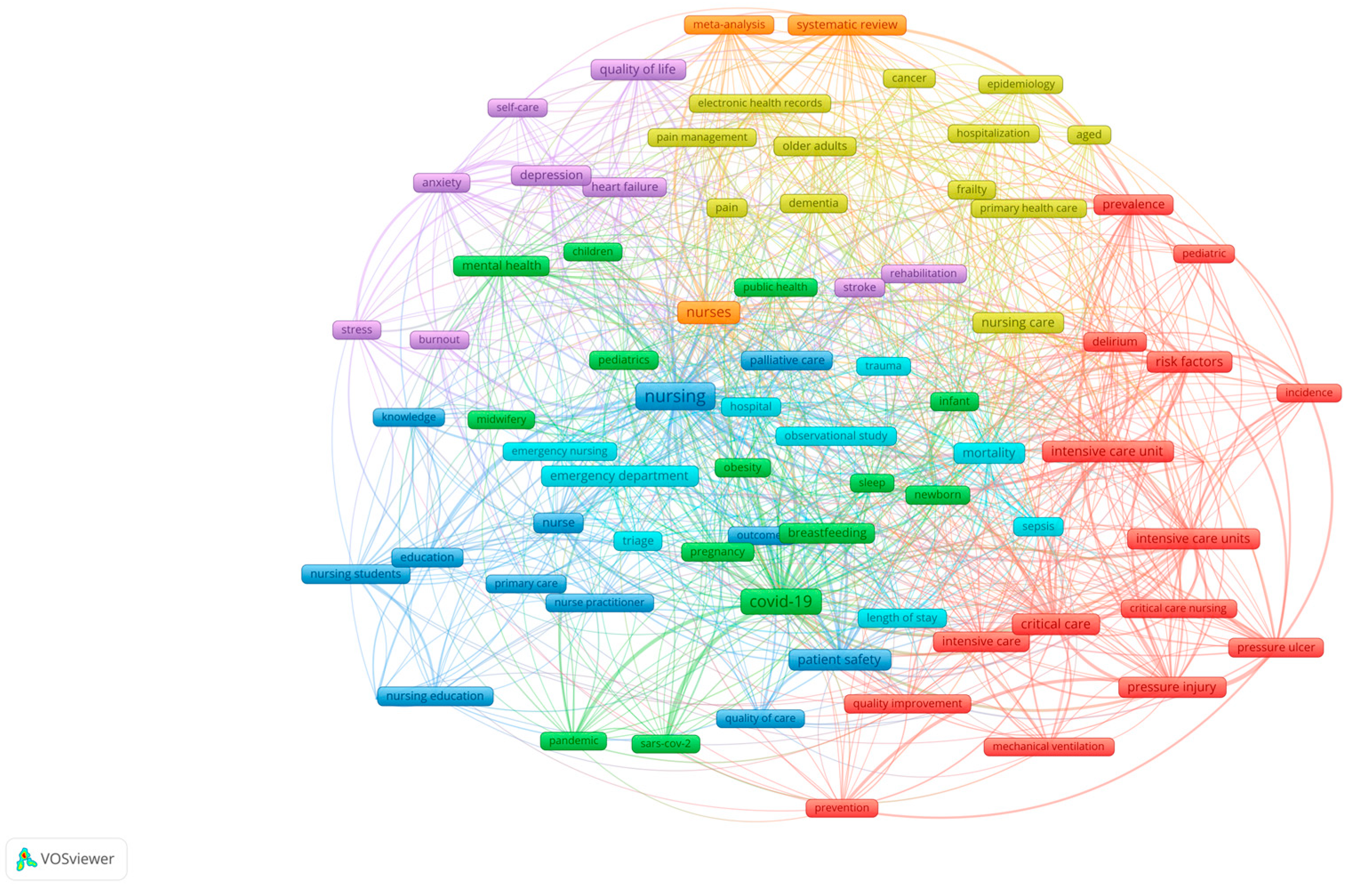

3.2. Syntetic Knowledge Synthesis of Nursing Observational, Retrospective and Other Quasi Experimental Studies

- Nursing education;

- Emergency and critical care nursing;

- Primary care nursing;

- Patient safety and quality of care;

- Pandemics;

- Midwifery;

- CVD rehabilitation;

- Quality of life and self-care/management for all ages;

- Pain management;

- Epidemiology from the nursing perspective.

3.3. Identifying a Sample of New Opportunities

3.4. Study Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q.; Lin, J.; Chi, A.; Davies, S. Practical Considerations of Utilizing Propensity Score Methods in Clinical Development Using Real-World and Historical Data. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 97, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katip, W.; Rayanakorn, A.; Oberdorfer, P.; Taruangsri, P.; Nampuan, T. Short versus Long Course of Colistin Treatment for Carbapenem-Resistant A. Baumannii in Critically Ill Patients: A Propensity Score Matching Study. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenzien, F.; Schmelzle, M.; Pratschke, J.; Feldbrügge, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, J.J.; Tan, H.-L.; Cipriani, F.; et al. Propensity Score-Matching Analysis Comparing Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Limited Liver Resections of the Posterosuperior Segments: An International Multicenter Study. Ann. Surg. 2024, 279, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langworthy, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, M. An Overview of Propensity Score Matching Methods for Clustered Data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2023, 32, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Antoniades, A.; Garolla, A.; Tozzi, F.; Todisco, P. Predictors of Psychopathology Response in Atypical Anorexia Nervosa Following Inpatient Treatment: A Propensity Score Matching Study of Weight Suppression and Weight Loss Speed. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 57, 1002–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.V.; Schneeweiss, S.; Franklin, J.M.; Desai, R.J.; Feldman, W.; Garry, E.M.; Glynn, R.J.; Lin, K.J.; Paik, J.; Patorno, E.; et al. Emulation of Randomized Clinical Trials With Nonrandomized Database Analyses. JAMA 2023, 329, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Liao, W.; Zhang, W.-G.; Chen, L.; Shu, C.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Chen, Y.-F.; Lau, W.Y.; Zhang, B.-X.; et al. A Prospective Study Using Propensity Score Matching to Compare Long-Term Survival Outcomes After Robotic-Assisted, Laparoscopic, or Open Liver Resection for Patients With BCLC Stage 0-A Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.W.; Maldonado, D.R.; Kowalski, B.L.; Miecznikowski, K.B.; Kyin, C.; Gornbein, J.A.; Domb, B.G. Best Practice Guidelines for Propensity Score Methods in Medical Research: Consideration on Theory, Implementation, and Reporting. A Review. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2022, 38, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-H.; Stuart, E.A. Propensity Score Methods for Observational Studies with Clustered Data: A Review. Stat. Med. 2022, 41, 3612–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim Valojerdi, A.; Janani, L. A Brief Guide to Propensity Score Analysis. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2018, 32, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S.; Jonsson-Funk, M.; Brookhart, M.A.; Rosenberg, S.A.; O’Shea, T.M.; Daniels, J. An Empirical Comparison of Tree-Based Methods for Propensity Score Estimation. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 1798–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facciorusso, A.; Kovacevic, B.; Yang, D.; Vilas-Boas, F.; Martínez-Moreno, B.; Stigliano, S.; Rizzatti, G.; Sacco, M.; Arevalo-Mora, M.; Villarreal-Sanchez, L.; et al. Predictors of Adverse Events after Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided through-the-Needle Biopsy of Pancreatic Cysts: A Recursive Partitioning Analysis. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R. Propensity Score. In Handbook of Matching and Weighting Adjustments for Causal Inference; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-10267-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.W.; Greene, T.J.; Swartz, M.D.; Wilkinson, A.V.; DeSantis, S.M. Propensity Score Stratification Methods for Continuous Treatments. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 1189–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, C.F.; Krzywinski, M.; Altman, N. Propensity Score Weighting. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Li, F.; Wang, R.; Li, F. Propensity Score Weighting for Covariate Adjustment in Randomized Clinical Trials. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 842–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, K.; Tena, J.D.; Detotto, C. Causal Inference with Observational Data: A Tutorial on Propensity Score Analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2023, 34, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liau, M.Y.Q.; Toh, E.Q.; Muhamed, S.; Selvakumar, S.V.; Shelat, V.G. Can Propensity Score Matching Replace Randomized Controlled Trials? World J. Methodol. 2024, 14, 90590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. To Use or Not to Use Propensity Score Matching? Pharm. Stat. 2021, 20, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottigliengo, D.; Baldi, I.; Lanera, C.; Lorenzoni, G.; Bejko, J.; Bottio, T.; Tarzia, V.; Carrozzini, M.; Gerosa, G.; Berchialla, P.; et al. Oversampling and Replacement Strategies in Propensity Score Matching: A Critical Review Focused on Small Sample Size in Clinical Settings. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Bai, H. Propensity Score Methods in Nursing Research: Take Advantage of Them but Proceed With Caution. Nurs. Res. 2016, 65, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Xie, L.; Duan, Z. Impact of Workplace Violence against Psychological Health among Nurse Staff from Yunnan-Myanmar Chinese Border Region: Propensity Score Matching Analysis. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Wang, H.; Fan, L. The Impact of Home and Community Care Services Pilot Program on Healthy Aging: A Difference-in-Difference with Propensity Score Matching Analysis from China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 110, 104970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.; Kim, E.-Y.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, H.-R.; Choi, S.; Yoon, Y.S.; Kim, E.; Heo, S.-J.; Jung, S.Y.; Jang, J. The Effects of Special Nursing Units in Nursing Homes on Healthcare Utilization and Cost: A Case-Control Study Using Propensity Score Matching. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 147, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Shen, Z.; Li, Q.; Ma, M.; Xu, D.; Tarimo, C.S.; Gu, J.; Wei, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, L.; et al. Understanding the Impact of Chronic Diseases on COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Using Propensity Score Matching: Internet-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 2165–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, T.; Srivastava, S.; Muneera, K.; Kumar, M.; Kelekar, U. Treatment for Insomnia Symptoms Is Associated with Reduced Depression Among Older Adults: A Propensity Score Matching Approach. Clin. Gerontol. 2024, 47, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A.; Edwards, N.; Fleiszer, A. Empty Systematic Reviews: Hidden Perils and Lessons Learned. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, R.W.; Sigafoos, J. ‘Empty’ Reviews and Evidence-Based Practice. Evid.-Based Commun. Assess. Interv. 2009, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, J.; Montgomery, P.; Hopewell, S.; Shepard, L.D. Empty Reviews: A Description and Consideration of Cochrane Systematic Reviews with No Included Studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, L.; Chiappinotto, S.; Palese, A. Exploring the Nexus between the Standardized Nursing Terminologies and the Unfinished Nursing Care Phenomenon: An Empty Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl. 2025, 36, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.S.R.; Baixinho, C.L.; Bernardes, R.A.; Ferreira, Ó.R. Nursing Interventions for Head and Neck Cancer Patients That Promote Embracement in the Operating Room/Surgery Unit: A Near-Empty Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2022, 12, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokol, P. Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis in Hospital Libraries. J. Hosp. Librariansh. 2024, 24, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokol, P. The Use of AI in Software Engineering: A Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis of the Recent Research Literature. Information 2024, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Li, G.; Hao, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Liu, S.; Yu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Ma, Y.; Fan, L.; et al. Psychological Depletion in Physicians and Nurses Exposed to Workplace Violence: A Cross-Sectional Study Using Propensity Score Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 103, 103493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, T.; He, J.; Wang, B.; Li, P.; Ning, N.; Chen, H. Effects of Nurses-Led Multidisciplinary-Based Psychological Management in Spinal Surgery: A Retrospective, Propensity-Score-Matching Comparative Study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Chen, P.; Molassiotis, A.; Jeon, S.; Tang, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Yu, Y.; Knobf, T.M.; et al. Measurement Invariance of the 10-Item Resilience Scale Specific to Cancer in Americans and Chinese: A Propensity Score–Based Multidimensional Item Response Theory Analysis. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.J.; Cheng, M.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Tang, Y.; Liang, J.; Sun, Z.; Liang, M.Z.; Yu, Y.L. Treatment Decision Making and Regret in Parents of Children With Incurable Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2021, 44, E131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Fan, C.; Ren, X.; Bai, S.; Dong, H.; Wei, M.; Meng, H. Comparison of Anaesthesia-Related Outcomes in Patients Monitored by Newly Recruited Nurse Anaesthetists and Anaesthesiologists: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagijo, M.; Crone, M.; Bruinsma-van Zwicht, B.; van Lith, J.; Billings, D.; Rijnders, M. The Effect of CenteringPregnancy Group Antenatal Care on Maternal, Birth, and Neonatal Outcomes Among Low-Risk Women in the Netherlands: A Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Trial. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2024, 69, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevitt, C.M.; Stapleton, S.; Deng, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, K.; Jolles, D.R. Birth Outcomes of Women with Obesity Enrolled for Care at Freestanding Birth Centers in the United States. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2021, 66, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, B.; Lee, K.H.; Park, C.G. Does Hospitalisation Impact the Successful Ageing of Community-Dwelling Older Adults?: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis Using the Korean National Survey Data. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2022, 17, e12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, C.; Cheung, B.; Chu, K. A Comparative Study Regarding Distance Learning and the Conventional Face-to-Face Approach Conducted Problem-Based Learning Tutorial during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.-P.; Yeh, W.-Y.; Hsu, T.-F.; Chow, L.-H.; Chen, W.-C.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Shulruf, B.; Chen, C.-H.; Cheng, H.-M. Implementing a Flipped Classroom Model in an Evidence-Based Medicine Curriculum for Pre-Clinical Medical Students: Evaluating Learning Effectiveness through Prospective Propensity Score-Matched Cohorts. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikas, S.A.; Afshar, K.; Fischer, V. Does Voluntary Practice Improve the Outcome of an OSCE in Undergraduate Medical Studies? A Propensity Score Matching Approach. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Shin, T.G.; Park, J.E.; Lee, G.T.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, S.A.; Kim, S.; Hwang, N.Y.; Hwang, S.Y. Impact of Personal Protective Equipment on the First-Pass Success of Endotracheal Intubation in the ED: A Propensity-Score-Matching Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, R.; Sato, M.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Maeno, T.; Sano, C. The Association between the Self-Management of Mild Symptoms and Quality of Life of Elderly Populations in Rural Communities: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cea-Soriano, L.; Pulido, J.; Franch-Nadal, J.; Santos, J.M.; Mata-Cases, M.; Díez-Espino, J.; Ruiz-García, A.; Regidor, E.; Predaps Study Group. Mediterranean Diet and Diabetes Risk in a Cohort Study of Individuals with Prediabetes: Propensity Score Analyses. Diabet. Med. 2022, 39, e14768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundborg, L.; Åberg, K.; Liu, X.; Norman, M.; Stephansson, O.; Pettersson, K.; Ekborn, M.; Cnattingius, S.; Ahlberg, M. Midwifery Continuity of Care During Pregnancy, Birth, and the Postpartum Period: A Matched Cohort Study. Birth 2024, 52, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.; Smets, T.; De Schreye, R.; Faes, K.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Cohen, J.; Van den Block, L. Improved Quality of Care and Reduced Healthcare Costs at the End-of-Life among Older People with Dementia Who Received Palliative Home Care: A Nationwide Propensity Score-Matched Decedent Cohort Study. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamazaki, N.; Kamiya, K.; Nozaki, K.; Koike, T.; Miida, K.; Yamashita, M.; Uchida, S.; Noda, T.; Maekawa, E.; Yamaoka-Tojo, M.; et al. Trends and Outcomes of Early Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit for Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Cohort Study With Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Heart Lung Circ. 2023, 32, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Ryu, Y.; Sano, C. Association between Self-Medication for Mild Symptoms and Quality of Life among Older Adults in Rural Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2022, 58, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPeake, J.; Shaw, M.; Mactavish, P.; Blyth, K.G.; Devine, H.; Fleming, G.; Griffin, J.; Gemmell, L.; Grose, P.; Henderson, M.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes Following Severe COVID-19 Infection: A Propensity Matched Cohort Study. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2021, 8, e001080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfuku, M.; Nishigami, T.; Mibu, A.; Yamashita, H.; Imai, R.; Tanaka, K.; Kitagaki, K.; Hiroe, K.; Sumiyoshi, K. Effect of Perioperative Pain Neuroscience Education in Patients with Post-Mastectomy Persistent Pain: A Retrospective, Propensity Score-Matched Study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5351–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekhail, N.; Costandi, S.; Saweris, Y.; Armanyous, S.; Chauhan, G. Impact of Biological Sex on the Outcomes of Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients with Chronic Pain. Pain Pract. 2022, 22, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.M.; Patorno, E.; Desai, R.J.; Glynn, R.J.; Martin, D.; Quinto, K.; Pawar, A.; Bessette, L.G.; Lee, H.; Garry, E.M.; et al. Emulating Randomized Clinical Trials With Nonrandomized Real-World Evidence Studies First Results From the RCT DUPLICATE Initiative. Circulation 2021, 143, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucly, A.; Savale, L.; Jaïs, X.; Bauer, F.; Bergot, E.; Bertoletti, L.; Beurnier, A.; Bourdin, A.; Bouvaist, H.; Bulifon, S.; et al. Association between Initial Treatment Strategy and Long-Term Survival in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes of Nursing Observational Studies | Opportunities Translated from General Healthcare Research Where PSM was Used |

|---|---|

| Nursing education | Comparing distance/blended and face-to-face learning [43,44], does voluntary clinical practice improve study outcomes [45]? |

| Emergency and critical care nursing | Impact of personal protective equipment [46]. |

| Primary care nursing | Effectiveness of self-management in the elderly [47], effectiveness of diets in chronic diseases [48]. |

| Patient safety and quality of care | Patient safety and efficiency of the health of robots [49]. |

| Midwifery | The effects of midwifery continuity care on delivery [49], association of quality of care with healthcare costs [50]. |

| CVD rehabilitation | Effectiveness of early rehabilitation in intensive units [51]. |

| Quality of life and self-care/management | Association between self-medication for mild symptoms and quality of life among older adults [52], long-term effects of severe COVID-19 [53]. |

| Pain management | Effect of perioperative pain neuroscience education [54], impact of biological sex patients with chronic pain [55]. |

| Epidemiology | Emulating randomized clinical trials with nonrandomized real-world evidence studies [56], association between initial treatment strategy and long-term survival [57]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blažun Vošner, H.; Kokol, P.; Završnik, J. Propensity Score Matching: Identifying Opportunities for Future Use in Nursing Studies. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050142

Blažun Vošner H, Kokol P, Završnik J. Propensity Score Matching: Identifying Opportunities for Future Use in Nursing Studies. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(5):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050142

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlažun Vošner, Helena, Peter Kokol, and Jernej Završnik. 2025. "Propensity Score Matching: Identifying Opportunities for Future Use in Nursing Studies" Nursing Reports 15, no. 5: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050142

APA StyleBlažun Vošner, H., Kokol, P., & Završnik, J. (2025). Propensity Score Matching: Identifying Opportunities for Future Use in Nursing Studies. Nursing Reports, 15(5), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050142