Behind the Scenarios: World View, Ideologies, Philosophies. An Analysis of Hidden Determinants and Acceptance Obstacles Illustrated by the ALARM Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method and Building Blocks

2.1. World Views

2.2. What Are “Scenarios”?

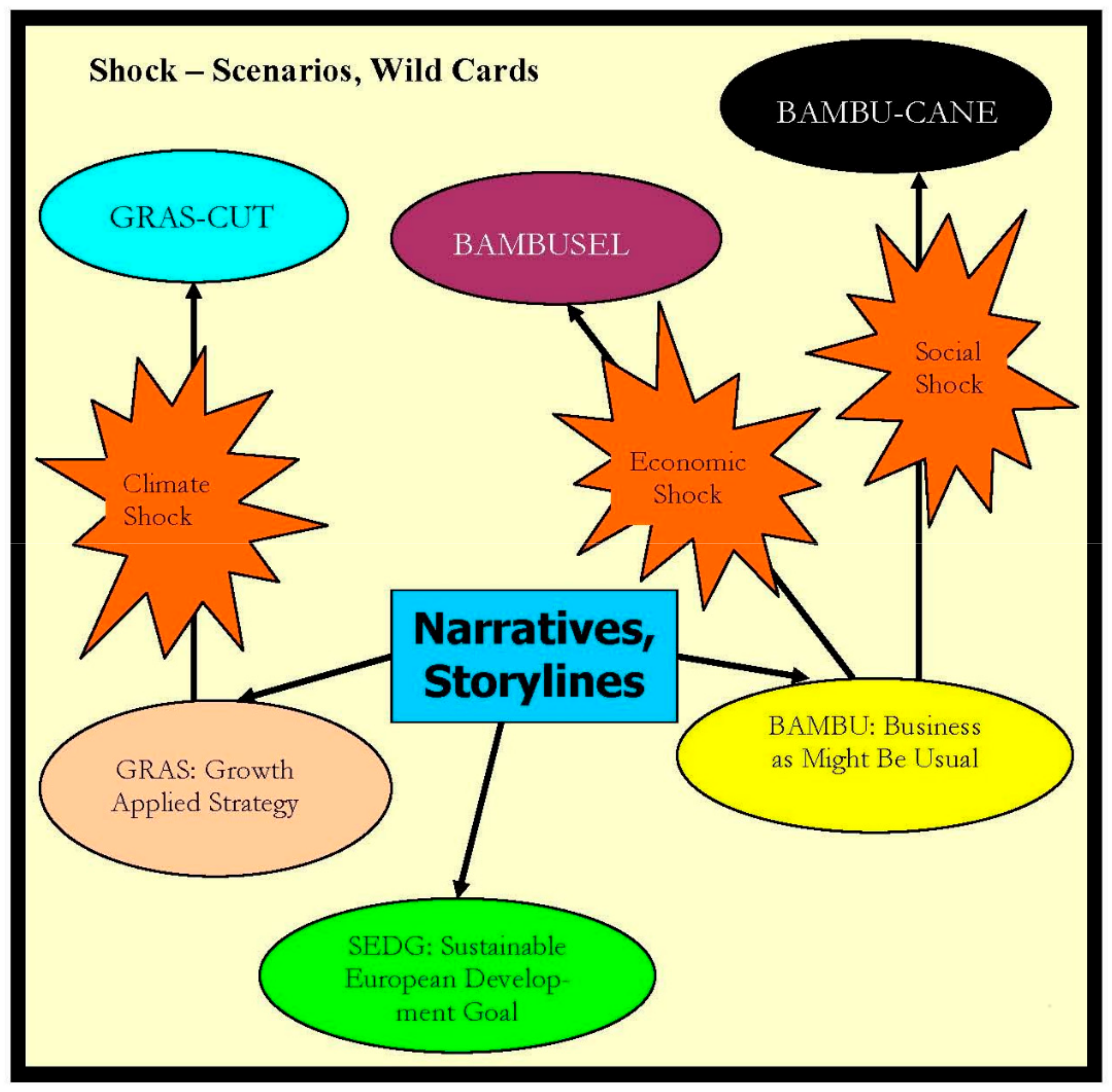

2.3. The ALARM Scenarios

- “Business As Might Be Usual” (BAMBU) is a policy-driven scenario, that is, a scenario extrapolating the expected trends in EU decision making and assessing their intended sustainability and biodiversity impacts materialise. Policy decisions already made in the EU are implemented and enforced. However, BAMBU is no business as usual scenario, based on trend extrapolation, since recent or upcoming changes in EU policies would have been ignored that way. At the national level as well as in the EU, deregulation and privatisation continue except in “strategic areas.” Internationally, there is free trade. Environmental policy is mainly perceived as another technological challenge.

- “GRowth Applied Strategy” (GRAS) is a coherent liberal, growth-focussed policy scenario. It includes deregulation, free trade, growth and globalisation as policy objectives actively pursued by governments. Environmental policies will focus on damage repair and limited prevention based on cost-benefit calculations, with no emphasis on biodiversity beyond the preservation of ecosystem services ESS.

- “Sustainable European Development Goal” (SEDG) is a backcasting (inverse projection) scenario and as such it is necessarily normative, designed to meet specific goals and deriving the necessary policy measures to achieve them, for example, a stabilisation of GHG emissions. It aims at enhancing the sustainability of societal development by integrated social, environmental and economic policy. Policy priorities under SEDG are a competitive economy and a healthy environment, gender equity and international co-operation. SEDG represents a precautionary approach, taking measures under uncertainty to avoid not yet fully known future damages.

2.4. The Shocks

- Cooling Under Thermohaline collapse (GRAS-CUT) is the environmental shock. It describes a collapse of the Atlantic Ocean water circulation (the most familiar part of it being the Gulf Stream) and the resulting relative cooling of Europe; indications observed by now.

- Shock in Energy price Level (BAMBU-SEL) describes the economic shock of a permanent quadrupling of the energy price, as expected when Peak Oil, the global maximum of oil production, occurs or political or other influences limit the supply significantly and permanently. We had a flavour of that in 1972, 1978 and 2008.

- ContAgious Natural Epidemic (BAMBU-CANE) is the social shock, a pandemic out of control. Again, we had a flavour of that, with the Chinese bird flu in 2006 and the Mexican swine flu in 2009 which permitted to observe the political and psychological mechanisms at work, regardless of their relatively limited global health impacts. In 2018, the WHO and Bill Gates, as chairman of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, warn of such a pandemic being unavoidable if not imminent [37].

3. Results—Comparing the Scenarios and Their Background Assumptions

- GRAS consistently provides the least desirable outcome for biodiversity in Europe—across different biomes and for most ecosystems and species.

- “Muddling through” along the BAMBU path, although probably slowing down biodiversity losses, will systematically fail to meet the EU target to end the loss of biodiversity, by 2020 and beyond.

- From a biodiversity point of view, SEDG represents a significant step in the right direction, although not sufficient in every respect (in some biomes some species and ecosystems would still be lost).

- GRAS-CUT would reduce the average European temperatures to the level of the early 20th century. Minor declines in harvest could be compensated by imports or incremental diet changes.

- BAMBU-SEL represents an immediate burden on the economy which however recovers after shrinking significantly. More permanent damage is caused for the environment (by maximising biofuels at the expense of biodiversity) and the levels of disposable income (due to money transfers to oil exporting countries).

- BAMBU-CANE would lead to a collapse of the economy if more than 20% of the population left their occupations to seek shelter in their countryside houses; it does not kick-start again when they return.

3.1. The World Views in the Scenarios: Ontologies, Anthropologies, Axiologies

3.2. The World Views in the Scenarios: Economic Orientations

3.3. The World Views in the Scenarios: Social Models and Welfare Regimes

- The liberal model: if interview partners supported state responsibility for securing individual income levels in at least two of the three cases “illness,” “old age” and “unemployment” but not beyond. These preferences were implemented in GRAS.

- The welfare state model: if in addition interviewees saw state responsibility for “reduction of income disparities,” or “provision of jobs,” or both. This corresponds to the BAMBU scenario assumptions.

- The etatistic model: if in addition they supported the control of salaries by law (implying a redistributive tax system), or a legally guaranteed general, tax financed basic income. Not all but some elements were included in SEDG.

3.4. The World Views in the Scenarios: Epistemologies and Science Implications

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. The Role of Science

4.2. World View Based Science—Policy Resonance: Support for the Research Hypothesis

4.3. Policies and World Views—The Probably Most Prominent Example

“To me, the most important question seems to be: how can we achieve zero growth in this society? It is beyond doubt for me, that this zero growth must be achieved in our industrial societies, in America, Western Europe and Japan. ... Should we not succeed in doing so, then the distance, the tensions between arm and rich nations will become bigger and bigger. ... It would be an illusion and even a lie to pretend there could be no growth for the Third World economies unless we were performing growth as well. I am worried however whether we will manage to get those powers under control, which strive for a permanent growth. Our whole societal system insists on growth—not only single companies, big business, multinational giants.”(own translation)

4.4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- OECD 2018. GDP Long-Term Forecast. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/gdp-long-term-forecast/indicator/english_d927bc18-en (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- IATA 2017. 2036 Forecast Reveals Air Passengers Will Nearly Double to 7.8 Billion. IATA Press Release No.: 55, 24 October 2017. Available online: http://www.iata.org/pressroom/pr/Pages/2017-10-24-01.aspx (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Johnson, P. 99 Facts on the Future of Business in the Digital Economy 2017. Available online: https://de.slideshare.net/sap/99-facts-on-the-future-of-business-in-the-digital-economy-2017 (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Samaniego, L.; Thober, S.; Kumar, R.; Wanders, N.; Rakovec, O.; Pan, M.; Zink, M.; Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.F.; Marx, A. Anthropogenic warming exacerbates European soil moisture droughts. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, S.B.; Dawson, R.J.; Kilsby, C.; Lewis, E.; Ford, A. Future heat-waves, droughts and floods in 571 European cities. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 034009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Shanahan, D.F.; Di Marco, M.; Allan, J.; Laurance, W.F.; Sanderson, E.W.; Mackey, B.; Venter, O. Catastrophic Declines in Wilderness Areas Undermine Global Environment Targets. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 2929–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W. Limits to Growth; A Report to the Club of Rome; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Randers, J.; Meadows, D.L. Limits to Growth; The 30-Year Update; Chelsea Green Publishing Company: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Late Lessons from Early Warnings: The Precautionary Principle 1896–2000; Environmental Issue Report No. 22; Office for the Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Late LESSONS from Early Warnings: Science, Precaution, Innovation; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Indicators for Sustainable Development. In Routledge International Handbook of Sustainable Development; Redclift, M., Springett, D., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 308–322. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. World views, interests and indicator choices. In Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indicators and Indices; Bell, S., Morse, S., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Machiavelli, N. Il Principe; Giunta: Firenze, Italy; Blado: Roma, Italy, 1532. Quoted from the German edition: Der Fürst; Insel Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Looking Back on Looking Forward: A Review of Evaluative Scenario Literature; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morus, T. Utopia; De Optimo Rei Publicae Statu: Basel, Switzerland, 1517. [Google Scholar]

- Settele, J.; Hammen, V.; Hulme, P.; Karlson, U.; Klotz, S.; Kotarac, M.; Kunin, W.; Marion, G.; O’Connor, M.; Petanidou, T.; et al. ALARM: Assessing LArge-scale environmental Risks for biodiversity with tested Methods. GAIA 2005, 14, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settele, J.; Penev, L.; Georgiev, T.; Grabaum, R.; Grobelnik, V.; Hammen, V.; Klotz, S.; Kotarac, M.; Kühn, I. Atlas of Biodiversity Risk; Pensoft: Sofia, Bulgaria; Moscow, Russia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.E.; Cobb, J.B., Jr.; Cobb, C.W. For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy towards Community, the Environment and a Sustainable Future; Green Print: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, M. The Five Worldviews That Define American Politics. Salon Magazine, 2011. Available online: https://www.salon.com/2011/01/12/lind_five_worldviews (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Hedlund-de Witt, A. Exploring worldviews and their relationships to sustainable lifestyles: Towards a new conceptual and methodological approach. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 84, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. The world we see shapes the world we create: How the underlying worldviews lead to different recommendations from environmental and ecological economics—The green economy example. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 19, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, D.; Apostel, L.; De Moor, B.; Hellemans, S.; Maex, E.; Van Belle, E.; Van der Veken, J. World Views: From Fragmentation to Integration; VUB Press: Brussels, Belgium, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Giddens, A.; Lash, S. Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Zukunftsfähigkeit als Leitbild? Leitbilder, Zukunftsfähigkeit und die reflexive Moderne. In Reflexive Lebensführung; Hildebrandt, E., Linne, G., Eds.; Zu den Sozialökologischen Folgen Flexibler Arbeit; Edition Sigma: Berlin, Germany, 2000; pp. 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bentham, J. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation; Reprint of the 1823 edition, with revisions by the author of the 1789 original publication; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, J.; Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T. From rational actor to efficient complexity manager: Exorcising the ghost of Homo economicus with a unified synthesis of cognition research. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 114, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, K.; Konstantakos, L.; Carrasco, A.; Carmona, G.L. Sustainable Development, Wellbeing and Material Consumption: A Stoic Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, P.G. Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change; Baker Academic: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alcamo, J. Scenarios as tools for international environmental assessments. In EEA European Environment Agency Expert Corner Report ‘Prospects and Scenarios’ No. 5; Office for the Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainability and the Challenge of Complex Systems. In Theories of Sustainable Development; Enders, J.C., Remig, M., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Looking to the Future: Finding Suitable Models and Scenarios. In Towards the Ethics of a Green Future. The Theory and Practice of Human Rights for Future People; Düwell, M., Bos, G., Steenbergen, N.V., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Limits to Growth Was Right. New Research Shows We’re Nearing Collapse. The Guardian, 2014. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/sep/02/limits-to-growth-was-right-new-research-shows-were-nearing-collapse (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Rosa, I.M.D.; Pereira, H.M.; Ferrier, S.; Alkemade, R.; Acosta, L.A.; Akcakaya, H.R.; den Belder, E.; Fazel, A.M.; Fujimori, S.; Harfoot, M.; et al. Multiscale scenarios for nature futures. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1416–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronzek, S.; Carter, T.R.; Jylhä, K. Representing two centuries of past and future climate for assessing risks to biodiversity in Europe. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 21, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginster, I.; Rounsevell, M.; Butler, A.; Dedoncker, N. Land use change scenarios for Europe. In Atlas of Biodiversity Risk; Settele, J., Penev, L., Georgiev, T., Grabaum, R., Grobelnik, V., Hammen, V., Klotz, S., Kotarac, M., Kühn, I., Eds.; Pensoft Publ.: Sofia, Bulgaria; Moscow, Russia, 2010; pp. 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Bondeau, A.; Carter, T.R.; Fronzek, S.; Jaeger, J.; Jylhä, K.; Kühn, I.; Omann, I.; Paul, A.; Reginster, I.; et al. Scenarios for investigating risks to biodiversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, J. Are We Prepared for the Looming Epidemic Threat? The Guardian, 18 March 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/18/end-epidemics-aids-ebola-sars-sunday-essay (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Hickler, T.; Vohland, K.; Feehan, J.; Miller Paul, A.; Smith, B.; Costa, L.; Giesecke, T.; Fronzek, S.; Carter Timothy, R.; Cramer, W.; et al. Projecting the future distribution of European potential natural vegetation zones with a generalized, tree species-based dynamic vegetation model. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 21, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderbaum, P. Issues of paradigm, ideology, and democracy in sustainability assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderbaum, P. Ecological economics in relation to democracy, ideology and politics. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 95, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funtowicz, S.O.; Strand, R. Models of Science and Policy. In Biosafety First: Holistic Approaches to Risk and Uncertainty in Genetic Engineering and Genetically Modified Organisms; Traavik, T., Lim, L.C., Eds.; Tapir Academic Press: Trondheim, Norway, 2007; pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Opielka, M. Gerechtigkeit durch Sozialpolitik? Utopie Kreativ 2006, 186, 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, I.; Boutilier, R.G. Social license to operate. In SME Mining Engineering Handbook; Darling, P., Ed.; Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration: Littleton, CO, USA, 2011; pp. 1779–1796. [Google Scholar]

- Falck, W.E.; Spangenberg, J.H. Selection of Social Demand-Based Indicators: EO-based Indicators for Mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, H. The Imperative of Responsibility. In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T. Moral responsibility and the business and sustainable development assemblage: A Jonasian ethics for the technological age. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 2, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Settele, J. Value pluralism and economic valuation—Defendable if well done. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 18, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, J.; Hölscher, M. Kulturelle Unterschiede in der Europäischen Union: Ein Vergleich Zwischen Mitgliedsländern, Beitrittskandidaten und der Türkei; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Czada, R. Institutionelle Theorien der Politik. In Lexikon der Politik; Nohlen, D., Schultze, H.O., Eds.; Droemer-Knaur: Munich, Germany, 1995; pp. 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Göhler, G. Wie verändern sich Institutionen? Leviathan 1997, 21–56, Sonderheft. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Institutional Sustainability Indicators: An Analysis of the Institutions in Agenda 21 and a Draft Set of Indicators for Monitoring their Effectivity. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Hot air or comprehensive progress? A critical assessment of the SDGs. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Political Economies of the Welfare State. Int. J. Sociol. 1990, 20, 92–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Beyond Growth. The Economics of Sustainable Development; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rink, D.; Wächter, M. Naturverständnisse in der Nachhaltigkeitsforschung. In Sozial-Ökologische Forschung. Ergebnisse der Sondierungsprojekte aus dem BMBF-Förderschwerpunkt; Balzer, I., Wächter, M., Eds.; Ökom-Verlag: München, Germany, 2002; pp. 339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Economic sustainability of the economy: Concepts and indicators. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. Sustainability: The need for societal discourse. In Civil Society for Sustainability. A Guidebook for Connecting Science and Society; Renn, O., Reichel, A., Bauer, J., Eds.; Europäischer Hochschulverlag: Bremen, Germany, 2012; pp. 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer, F. A multidisciplinary sustainability understanding for corporate strategic management. In Proceedings of the 18th ISDRS Conference, Hull, UK, 24–26 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, M.; Limoges, C.; Nowotny, H.; Schwartzman, S.; Scott, P.; Trow, M. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies; SAGE Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Funtowicz, S.O.; Ravetz, J.R. Science for the post-normal age. Futures 1993, 25, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunz, S.; Gawel, E. Transformative Wissenschaft: Eine kritische Bestandsaufnahme der Debatte. GAIA 2017, 26, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissel, C.V. Die Eigenlogik der Wissenschaft neu verhandeln: Implikationen einer transformativen Wissenschaft. GAIA 2015, 24, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.A. Economists, value judgements, and climate change: A view from feminist economics. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestel, E. Jenseits der Grenzen des Wachstums: Bericht an den Club of Rome; Verlagsanstalt: Stuttgart, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Juncker, J.-C. G7 Press Conference of EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, 7 June 2015. Available online: https://www.europa-nu.nl/id/vjulg37huam9/nieuws/speech_full_transcript_of_the_g7_press?ctx=vhyzn0sukawp (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- European Commission. Europe 2020. A European Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Towards Green Growth; OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Towards a GREEN Economy—Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication; A Synthesis for Policy Makers; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Ideology and Practice of the ‘Green Economy’—World Views Shaping Science and Politics; Birnbacher, D., Thorseth, M., Eds.; The Politics of Sustainability: Philosophical Perspectives; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar]

| Scenario | GRAS | BAMBU | SEDG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate envelope | fits to the IPCC SRES-A1FI storyline and its assumptions | SRES A2 (the best fitting available SRES scenario at the time of calculation) | SRES-B1 scenario (lowest SRES scenario available, 450 ppm not in SRES. B1 and SEDG story lines differ significantly) |

| CAP | Dismantling payments for production and for 2nd pillar (rural development & environment) | Shift 1st to 2nd pillar results in polarisation: intensification of high yielding locations, neglect of low yielding ones | Spatially explicit support structure to maintain (organic) agriculture throughout the landscape (only 2nd pillar transfers) |

| EU Funds | Phasing out, considered as subsidies | Focussed on infrastructure development and growth in poor regions | Focussed on local green development and opportunities, education and employment |

| Energy Policy | Efficiency, some renewables based on cost calculations | Efficiency, aiming at 20% reduction of GHG emissions by 2020 and 80% by 2080. Increase nuclear and renewables | Aiming at ¾ reduction of CO2-emissions by 2050 through savings, changing consumption patterns and renewables |

| Transport Policy | Increased efficiency due to market pressure, no policy to shift the mode of transport or reduce transport volumes | Technological improvements and changing the share of different modes of mobility (walking, biking, trains, cars, boats, planes: modal split) | Transport reduction priority, plus modal split change (through pricing and infrastructure supply), technical improvements |

| Chemicals Policy | Focus on innovation and competitiveness. REACH not consequently implemented | REACH implemented | REACH plus; filling gaps for example, for metals, nanomaterials, endocrine disruptors |

| Trade Policy | Strong support for WTO and free trade | Promoting free trade except in “strategic areas” | Global sourcing reduced due to cost reasons; phytosanitarian controls |

| GRAS | Three to four capital stocks, non-declining sum, mutually substitutable (weak sustainability), the economy considered as having primacy. Processes including overshoot are reversible. Assumption that once the economy works properly, all other parts of the puzzle will fall in place, that is, social and environmental problems will be solved automatically (the Kuznets- and Environmental Kuznets Curve hypotheses). Focus on adaptation (managing impact), optimal solutions by maximisation. |

| BAMBU | Three to four capital stocks, non-declining sum plus conservation of critical natural capital, mostly comparable and commensurable, attempts to go “beyond GDP,” weak to reasonable protection standards. Precautionary principle, safe minimum standards, some ambitious protection standards set but not vigorously enforced, focus on innovation for the market to deliver the desired goods or fully equivalent substitutes. Focus on mitigation (reducing pressures) and restoration (stabilizing the state), optimal solutions by optimisation. |

| SEDG | Co-evolution of four sub-systems, with each having its own reproduction criteria and mechanisms, plus demands to the impacts of each other. Earth is a closed system with limited resources, permanent growth is not possible. Precautionary principle, addressing drivers of environmental and social crises, focus on prevention (redirecting drivers) and mitigation (overcoming pressures) limiting human impact, long term resilient/healthy ecosystems providing ecosystem services. Assessment is only possible by MCA/MCDS, (socially) optimal solutions by legitimation. |

| ALARM | SRES | GEO-3 | Millennium Ecosystem Assessment | Roads from Rio+20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2100 | 2100 | 2032 | 2100 | 2050 |

| GRAS | A1FI | Markets First | Global Orchestration | Global Technology |

| BAMBU | A2 | Security First | Order from Strength | |

| SEDG | B1 | Policy First | TechnoGarden | Decentralized Solutions |

| B2 | Sustainability First | Adapting Mosaic | Consumption Change | |

| Settele et al., 2005 | IPCC et al., 2000 | UNEP 2002 | Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2003 | Kok et al., 2018 |

| Content | GRAS | BAMBU | SEDG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideological orientation | business as usual, sustained growth (macro) and profits (micro), quantitative, monetary criteria (no qualities) | ecological modernisation, qualitative growth, changes of aspects but not system basics, flexible adaptations | precaution, multi-dimensional objectives, limited win-win options, priority for justice, health and environment over net growth |

| Economic paradigm | Neoclassical | incoherent, neoclassical plus etatism, welfare state, technology, green growth | sustainability economics: ecological, evolutionary, institutional and political economics |

| Institutional arrangements | Institutions facilitating ‘corporate globalisation’ like IMF, World Bank, WTO | Focus on regional integration. EU a strong player in international institutions, modifying but not altering rules | Subsidiarity principle. For example, strengthening the UN, evaluating where the EU needs more and where it could have less competences and similarly so on the members state level |

| Orientation | GRAS | SEDG |

|---|---|---|

| Source of profit | Share value, speculation | Dividend, payment to owners |

| Ownership | Temporary, share-based | Permanent, individual |

| Level of profit | Fixed management objective, predetermined | Residual, after material, labour and finance costs |

| Perception of corporate success | Achievement of management and providers of finance (shareholders), at the expense of jobs and salaries | Achievement of partners, sharing of results |

| Salaries | Residual after material and finance costs, plus profit | Negotiated costs, based on productivity increase plus inflation compensation |

| Relation management/staff’ salaries | Management increasing with profit or more, salaries stagnate or decline to generate profit | Increasing in line |

| Industrial relation | Exploitation | Partnership |

| Sustainability ethics | Utilitarism | Fairness, procedural justice |

| No. State Responsibility | Liberal | Welfare State | Etatistic | Unclassified | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average EU 15 member states | 0.5 | 8.9 | 29.8 | 56.5 | 4.4 |

| Sweden | 0.7 | 20.2 | 40.9 | 34.5 | 3.7 |

| UK | 0.2 | 15.1 | 32.5 | 46.7 | 5.6 |

| France | 1.9 | 8.5 | 23.9 | 56.0 | 9.7 |

| W.-Germany | 0.8 | 13.7 | 46.8 | 34.0 | 4.7 |

| Average CEE EU member states | 0.5 | 4.7 | 21.8 | 69.1 | 3.9 |

| E.-Germany | 0.0 | 2.8 | 13.9 | 80.7 | 2.6 |

| Czech Republic | 2.2 | 12.1 | 24.2 | 54.8 | 6.8 |

| Poland | 0.4 | 3.1 | 17.2 | 76.7 | 2.6 |

| Hungary | 0.1 | 5.1 | 30.8 | 61.0 | 2.9 |

| Bulgaria | 0.0 | 6.7 | 12.1 | 76.7 | 4.6 |

| ALARM Scenario | Concept of Justice (in Aristotelian Nicomachean Ethics) | Institutional Level Involved | Famous Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisations | Mechanisms | Orientations | |||

| Steering System (Institutional Mechanism) | Social Relation, Typology of Reciprocity | Principle of Justice (Political) | |||

| GRAS | Equity based upon what people contribute (Iustitia Communitativa) | Market | Instrumental association, exchange | Performance | Robert Nozick |

| BAMBU | Equity of opportunity (no clear relation) | State (often serving business) | Citizenship | Equity | John Rawls |

| SEDG | Equity based on distribution, needs based (Iustitia Distributiva) | Community | Community Solidarity, Communicative action | Need satisfaction, equality | Amitai Etzoni |

| Equity based on enabling participation (Iustitia Universalis) | Legitimation | Political culture, human rights, communication of values | Participation, access, inclusion (N. Luhmann), global justice | Amartya Sen | |

| Variable | Indicators | Liberal = GRAS | Social = SEDG | BAMBU | Conservative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decommodification: protection against market forces and income loss | Level of income substitution, % of previous income. | Weak | Strong | Medium | Medium |

| Share of individual financing | High | Low | Medium | Medium | |

| Residualism | Share of basic support in total social expenditure | Strong | Limited | Medium to strong | Strong |

| Privatisation | Share of private expenditure for health and old age as share of total | High | Low to medium | Medium | Low to medium |

| Corporatism/Etatism | Number of social security systems for specific professions | Weak | Medium | Medium | Strong |

| Share of expenditures for life-long employed government staff | Minimised | Increasing | Medium | Medium | |

| Redistribution | Progression in (income) tax structure | Weak | Strong | Medium | Weak |

| Equality of transfers received | Weak | Strong | Medium | Weak to medium | |

| Full employment guaranty | Expenditures for active labour market policy | Low | Strong | Medium | Medium |

| Unemployment quota, weighted by labour force participation | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium | |

| Role of market in social security provision | Shares of transfers and recipients | Central | Marginal | Medium | Strong |

| Role of state in social security provision | Shares of transfers and recipients | Minimised | Central | Subsidiary to medium | Subsidiary |

| Role of family/community in social security provision | Shares of transfers and recipients | Subsidiary | Subsidiary | Marginal to subsidiary | Central |

| Role of human rights | Beyond legal status, respect in social life and employment | Medium | High | Medium to high | Medium |

| Dominant form of welfare state solidarity | Entitlement basis | Individual | Work focussed (in SEDG incl. unpaid work) | Labour focusses, tax support | Communitarian, etatistic |

| Dominant means of steering social policy | Agency and organising principle | Market, economic optimisation | State, equity principles for citizens/inhabitants | Mixed market and state, mixed ideas | Moral and economic |

| Underlying concept of social justice | As realised by institutional mechanisms | Equality of opportunity | Distributional justice | Opportunity & distribution | Fair participation, basic need satisfaction |

| Archetypical countries | Switzerland | USA | Sweden | EU | Italy, Germany |

| GRAS | SEDG | |

|---|---|---|

| Future value | Exponential discounting, positive discount rates | Object dependent: no, hyperbolic, linear or exponential discounting |

| Dynamics | Equilibrium with reversible deviations, series of equilibria, largely predictable, high inherent resilience | Nature and society are processes of continuous irreversible change, path dependent but unpredictable, with medium to high vulnerability |

| Resonance group of policy recommendations | Economic and fiscal policy makers, business | Policy makers, civil society |

| GRAS | BAMBU | SEDG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theory of science, mode | Positivism Mode 1 | Eclectic mix, positivism dominates, Mode 1 dominates | Social constructivism, subjectivism, hermeneutics, contextualism, Mode 2 dominates |

| Models of science-society relationship | The initial ‘modern’ model: perfection/perfectibility | The precautionary model, the model of framing & the model of science/policy demarcation | The model of extended participation: working deliberatively within imperfections |

| Role of scientists | Outside, truth speaks to power | different attitudes, scepticism about truth and power | Citizen scientist, post-normal science, sustainability science, discourse based. Participatory, multi-criteria and multi-perspective assessments |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spangenberg, J.H. Behind the Scenarios: World View, Ideologies, Philosophies. An Analysis of Hidden Determinants and Acceptance Obstacles Illustrated by the ALARM Scenarios. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072556

Spangenberg JH. Behind the Scenarios: World View, Ideologies, Philosophies. An Analysis of Hidden Determinants and Acceptance Obstacles Illustrated by the ALARM Scenarios. Sustainability. 2018; 10(7):2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072556

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpangenberg, Joachim H. 2018. "Behind the Scenarios: World View, Ideologies, Philosophies. An Analysis of Hidden Determinants and Acceptance Obstacles Illustrated by the ALARM Scenarios" Sustainability 10, no. 7: 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072556

APA StyleSpangenberg, J. H. (2018). Behind the Scenarios: World View, Ideologies, Philosophies. An Analysis of Hidden Determinants and Acceptance Obstacles Illustrated by the ALARM Scenarios. Sustainability, 10(7), 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072556