1. Introduction

A Socio-Ecological System (SES) is a system that can be defined at several spatial, temporal, and organizational scales and which may be hierarchically linked [

1,

2]. Usually, an SES is a dynamic and complex system with continuous adaptation of all the attributes [

1,

2,

3]. The system can also be defined as the biophysical and social constructs (for example, within a coastal society) that regularly interact in a resilient and sustained manner and, therefore, as a set of critical resources (natural, social, and cultural) whose flow and usages are regulated by a combination of ecological and social systems [

1,

3,

4]. The factors of the living environment (ecology and society) determine the category of ‘resilience,’ i.e., stability, adaptivity, or readiness [

5]. T. Crane [

6] reviews the importance of SES analysis and also suggests how empirical models of SESs can explain their interactions with livelihoods. The most robust livelihood systems are those with high resilience and low vulnerability [

7], while the most vulnerable livelihoods demonstrate the opposite [

8]. This is what the livelihood-resilience concept admits [

9]. That is, livelihood resilience refers to an individual household’s ability to absorb and recover from disturbances due to unexpected events and to adapt to the post-event conditions. Again, the adaptive dynamics are an inherent property of the SES, and there therefore exists a distinct interrelationship between SESs and livelihood resilience [

10].

Livelihood resilience can be understood in terms of resilience capacity (e.g., absorptive, adaptive, and transformative) and by its relevance to different dimensions of livelihood conditions (e.g., social, economic, political, cultural, environmental, etc.). Ayeb-Karlsson and their colleagues [

11] define livelihood resilience as ‘the capacity of all people across generations to sustain and improve their livelihood opportunities and well-being despite environmental, economic, social, and political disturbances.’ Therefore, understanding livelihood resilience helps to address the question of ‘resilience of what and for whom’ by focusing on the resilience of people’s livelihood strategies [

12,

13]. Marschke and Berkes [

14] claim that if a household’s livelihood strategies and activities are better prepared for coping with and adjusting to the impacts of any disturbances caused by unexpected shocks, they can be considered resilient. They also claim that adapting to the changing conditions resulting from these disturbances forms the process of livelihood resilience building, and this process is mostly influenced by characteristics of the SES. The nature and extent of resilience or vulnerability is thus a product of different characteristics of the SES, i.e., the discussion of vulnerability is important in resilience understanding because the vulnerability emphasizes the ability of a system to deal with a hazard, absorbing the disturbances or adopting to it, and also helps in exploring the policy options for dealing with future uncertainty and changes in the system [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Thus, it explains that socio-ecological system resilience is about people and nature as an interdependent system [

18], that influences the individual decision-making behaviour.

The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has employed a quantitative method of calculating the ‘resilience score’ from different factors related to economic, social, and environmental resources that contribute to making households resilient to an unexpected shock [

15]. This approach uses a systematic approach that assumes change is constant, and therefore that the livelihood resilience of an individual household can be described by the characteristics of stability, adaptive capacity, and readiness of the respective individual household to cope with an unexpected event. However, the status of livelihood resilience also depends on the available livelihood options and the ability to tackle risks. The ability to tackle risks also varies due to ex-ante and ex-post programme interventions taken by the household’s internal resources and external institutions. This can be considered using two well-known frameworks,

the process-oriented resilience framework and

the outcome-oriented resilience framework.

The process-oriented method considers the dynamic characteristics of the various factors when assessing livelihood resilience [

19]. It considers a 4-R model (risk recognition, resistance, redundancy, and rapidity) for the resilience assessment of an individual household.

Risk recognition refers to the degree of risk that an individual household recognizes during an event;

resistance examines its capacity and strength to withstand the disturbances caused due to the event;

redundancy refers to the extent of the substitution of resources in the aftermath of the event, whereas the

rapidity explains the duration of time required for the individual household to obtain access to internal and external support.

The outcome-oriented resilience framework proposed by the Department for International Development (DFID) assesses the outcomes of livelihoods after an extreme event [

20]. It is expected that, following any hazard, every individual household can be grouped into one of four outcomes: (i)

bounce-back better refers to those households better able to handle future risks; (ii)

bounce-back to status quo refers to a return to the pre-event status of the household; (iii)

recovered describes a situation worse than the household’s pre-event condition; and (iv)

collapse refers to the worst-case scenario in which the household loses its capability to deal with future shocks.

Process-oriented analysis describes the dynamic pattern in the resilience status of individual households, whereas

outcome-oriented analysis explains the static dimension of the same. The process-oriented framework does not, however, explain the continuity between different stages in the aftermath of an extreme event, and it is therefore difficult to identify strategies from livelihood resilience alone, and thus difficult to assess the influence of livelihood resilience on migration decisions.

To ‘opt to migrate’ or ‘opt not to migrate’ is a livelihood decision. The reasons for one’s ‘opting to migrate’ (hereafter ‘migration’) can also influence others’ ‘opting to not migrate’ (hereafter ‘non-migration’), even when all parties live within the same socio-ecological system (SES). However, this will not be so straightforward in every case, as the decision to migrate or not to migrate can be either voluntary or involuntary. Not every situation coerces migration, nor would everyone within a society wish to migrate, so the reasons for making a decision to migrate or not is very person-specific. A generalized explanation is therefore difficult to summarize. The purposes and causes of migration often vary, and it is difficult to know the root causes of population movement. The concept of ‘pull’ and ‘push’ factors is not new. The literature states that people choose migration as the last survival strategy to cope with livelihood struggles [

21,

22,

23]. The Foresights annual report [

24] has described five drivers that intrinsically influence migration decisions: social, economic, political, demographic, and environmental drivers. All five drivers are the integrated elements of an SES and influence livelihood resilience. It is projected that globally 10 million people may find themselves caught in vulnerable areas and unable to migrate due to resource constraints [

22]. There is, however, no conclusive consensus on whether the reasons for migration are contraproductive for causes of non-migration. That is, the reasons for which an individual household decides to migrate can also be the reason for other individual households to opt for non-migration from the same place.

Further, the livelihood scenario varies across SESs, together with the factors that influence livelihoods as nested in an SES, and is differentiated by multilevel systems that provide essential services to individual households, such as supply of food, energy, and water [

25,

26]. All these characteristics of an SES determine the adaptive capacity of an individual household. It is therefore important to know how characteristics of an SES influence the livelihood resilience of people living within the respective SESs and thus their decisions regarding migration. It should also be noted here that the migration or non-migration decision, as an alternative adaptive strategy, directly contributes to livelihood resilience. The present research therefore aims to ascertain how, and to what extent, livelihood resilience influences the migration decisions (to migrate or not to migrate) of people living in a vulnerable socio-ecological system. The specific objectives are:

to understand the dissimilarities of livelihood resilience across different socio-ecological systems;

to explore the influences of livelihood resilience on migration decisions and its discrepancies across different socio-ecological systems;

to analyse how the interrelationship between livelihood resilience and migration decisions can be useful for future climate-change adaptation policy planning.

To achieve these objectives, firstly an operational framework for livelihood resilience is developed (

Figure 1), then the way in which livelihood resilience is influenced by the dynamic characteristics of an SES is analysed, and finally the influence of interrelationships between SESs and livelihood resilience factors on the ‘migration decision’ (i.e., to migrate or not) is explained.

The conceptual framework (

Figure 1) explains the nexus between livelihood resilience and migration decisions of households living in an SES. According to this framework, an SES is a set of critical resources (natural, socio-economic, and political) whose flow and use is regulated by a combination of ecological and social systems. ‘Livelihood resilience’ is a product of the SES in which people live, and the decision of migrating or staying put depends on how factors of the SES (ecological and social attributes) impact their livelihood resilience within a particular context of disruptions (environmental, social, political, or economic). It is assumed, in addition, that people opt for non-migration if their livelihood is resilient to external shocks. This assumption infers that resilience is an exogenous characteristic of the system, whereas coupled influence of both the endogenous and exogenous characteristics of the livelihood determine the livelihood resilience. Taking this limitation of analytical concept, in the course of the present research, the outcome-oriented approach of resilience analysis is employed, and empirical application of the conceptual framework presented in

Figure 1 is undertaken. This paper addresses these issues based on empirical evidence from five rural communities in Bangladesh.

Section 2 describes the methodology, including the study area, the development of livelihood-resilience measurement, characteristics and types of socio-ecological systems, and migration patterns.

Section 3 presents the results in light of the stated objectives.

Section 4 discusses the results and

Section 5 concludes the paper.

3. Results

Based on the analytical framework described in

Section 2, this section presents, firstly, the identified SES characteristics; secondly, the livelihood-resilience patterns across the SESs; and, finally, the interrelationship between livelihood characteristics and migration decisions.

3.1. Characteristics of Socio-Ecological Systems

A summary of the SES characteristics is presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 3. Two major types of aquaculture practice, shrimp and Golda (a local variety of river prawn), are observed in the studied villages (see

Figure 3B). The extent of these practices depends upon and varies according to the availability of saline water, which is itself dependent on proximity to rivers. Two out of the five studied communities have no salinity problems and therefore more opportunity for rice production, which helps in keeping the level of poverty low in these villages. Flooding is identified as the major hazard, usually occurring during monsoons due to heavy rainfall and long-standing water-logging problems.

It is observed that people living in Shovna village have the opportunity to produce rice three times in the year (see

Figure 3A). The villagers of Shovna mentioned that sources of fresh water are among the main reasons for threefold rice production. One of the major reasons is that this SES is hardly affected by any hazards (see

Figure 3C). They are free from saline water and have adequate irrigation facilities, and can therefore produce Aus, Aman, and Boro rice, creating employment opportunities for the wage-earner locally and thus reducing their dependency on seasonal migration. It is mostly those who are dependent on daily labour and work inside the community in farming or fishing who migrate seasonally, particularly during the Boro rice season. Such labourers are used to going for three months to the Gopalgonj, Madaripur, or Faridpur districts (northeast of Khulna district) to harvest Boro rice. They take rice instead of money in the form of cash as the mode of payment for their labour, bringing the collected rice back to their homes. Many seasonal migrant families reported that, with the rice received, their family can sustain at least 3–6 months, depending on the number of family members.

The majority of the people living in salt-water-dependent SESs (i.e., Chakdah village, on the border with India) reported the existence of more religious conflict compared to other SESs (

Figure 3E). Interestingly, people living in a mangrove-dependent community reported less religious conflict than in two other studied communities, one of which has a Hindu majority, the other a Muslim majority. Both of these are dependent on an irrigated-rice production system.

More poor people live in the mangrove-dependent community (i.e., Padmapukur) than others, whereas a smaller number of poor people live in a rain-fed agriculture SES, i.e., in Shovna. People living remote from the major cities are relatively poor in general as they cannot mobilize resources properly, and they therefore face frequent economic losses to productivity (

Figure 3D). They furthermore remain poor as they have very limited options for diversifying their livelihoods. In addition, almost everyone in Chakdah village thinks they face border problems between Bangladesh and India, while none in the other studied villages mention such problems.

3.2. Livelihood Resilience across SESs

Farming and fishing are identified as the main livelihood sources in the studied villages, followed by the wage-earning or so-called daily-labour group as a third main source of employment. This indicates that the majority of livelihood opportunities are dependent on natural resources. Farming and fishing cover about 50% to 70% of the listed livelihoods in each of the studied communities. The percentage of fishing is highest at Padmapukur village in the Uttar Bedkasi union (49%), while the percentage of farming is highest at Chakdah village in the Mathureshpur union (52%). Farming or fishing is the main source of livelihood in each community, but wage earning is the second source of livelihood in each, with the highest percentage at Vabanipur (32%). Fish trading, business, livestock rearing, remittance, and additional sources of livelihood appear to a very minimal degree.

Participants mentioned that the main challenge of living in mangrove-dependent SESs was that they had hardly any chance to farm rice, despite it being their staple food. They were therefore dependent on purchasing rice. They considered farming salt-water shrimp or any kind of prawn or fish a better source of earning more money, but the profit from shrimp farming was dependent on the scale of the farm, quality of production, and disease prevention. Most of those dependent on shrimp farming were therefore unable to recover from the shock derived from cyclone Aila and lost their livelihood, consequently being forced to migrate away from their communities (to nearby cities or even to India) for an alternative income source.

The level of resilience of these livelihood categories is analysed by characterizing the socio-ecological systems, and presented according to the outcome-oriented livelihood resilience framework in

Figure 4. Based on the framework employed and the statements of participants,

Figure 4 shows that only 6% of the people in their communities were able to bounce back better following cyclone Aila in 2009, and that they were living in largely agricultural SESs. Nobody living in a salt-water-shrimp- or a mangrove-dependent SES could bounce back better after cyclone Aila. The livelihood condition in a mangrove-dependent SES is again more vulnerable than a rain-fed agricultural SES (

Figure 4). It was even reported during discussion that people living in an irrigated-agricultural SES or a rain-fed agricultural SES had faced less trouble in returning to their pre-event condition.

There was no ‘collapsed livelihood resilience’ case in rain-fed agriculture, but ‘bounce back status quo’ shows the highest percentage and ‘bounce back better’ the lowest percentage. The majority of the ‘recovered’ resilience groups lived in salt-water shrimp SESs. The reasons for their recovery mentioned during discussion were twofold: firstly, having been inundated for several months, they could fish in the canals and rivers, and secondly, ample relief and reconstruction support from both the government and non-government sectors was made available.

3.3. Present (Non)Migration Infographic across SESs

3.3.1. Pattern—Seasonal, Circular, and Permanent

There was evidence of seasonal and circular migration in all kinds of SES. Seasonal migrants are those who migrate once or twice at a particular period of the year, usually when there is no available employment in their native communities, whereas the circular migrants are those who migrate regularly to earn money so that their families can stay in their place of origin. Both seasonal and circular migration are strategies for staying in one’s place of origin in the long term. The results of the field study show that a rain-fed agriculture SES includes fewer people practising temporary migration, whereas those from a salt-water shrimp SES practise comparatively more seasonal migration.

The studied salt-water shrimp SES is located in a border region (Bangladesh–India), where different kinds of opportunity to be involved in sustaining one’s livelihood are available. During discussions and even in in-depth interviews with the people living in this area, it was revealed that young people (mainly those who have dropped out of education) were involved in illegal markets, trafficking cattle, clothing, alcohol, drugs, rice, and lentils, for example, and then selling it on the black market. Some travelled illegally to India and worked there for two to six months in different sectors, from brick-field to hawker businesses. As the culture and customs of the Indian state of West Bengal is not different to those of Bangladesh, it is easy for them to assimilate themselves into society there even without a legal passport. In addition, they were well connected socially to their destination in India, and could therefore easily handle any legal action taken against them, should any occur.

In discussions on permanent migration with people living in the rain-fed agriculture and irrigated-agriculture SESs, merely five to ten families were reported as having permanently migrated from their villages during the previous five years, equal to less than 1% of their communities. They tended not to mention migration as a regularly occurring event, as those who migrated permanently had no option to stay. Rather than economic crisis, they were mostly involved in political conflict and troubled by legal actions, and therefore had to leave their place of origin. According to the perception of the discussants, those who permanently migrated from their villages usually went to India or to Dhaka. Once again, those who had permanently migrated from Padmapukur (a mangrove-dependent SES) after cyclone Aila had settled down in major cities, mainly in Khulna and Dhaka. However, the rates of permanent migration in the studied SESs were not so high, with around 2% of all households in the villages having migrated during the last five years.

Historically, the people in Chakdah village (a salt-water shrimp SES) travelled and worked illegally in India, before border restrictions became stricter. Differing from other studied SESs, however, they no longer have the confidence to travel to and work illegally in India without having any strong social networks in place. Usually, those who used to undertake seasonal migration to India have relatives there who arranged work for them. Some discussants reported that a few of them used to acquire tourist visas and worked in India. This began when the Indian High Commission decentralized their consulate services to a divisional level in Bangladesh, allowing people to acquire multiple-entry visas for longer periods of time. On the other hand, earnings in India are comparatively better than in Bangladesh due to divergence in the value of the currency of payment.

3.3.2. Immigration

Interestingly, discussants of the mangrove-dependent SES reported that, after Aila, at least five families had immigrated to their communities, and had been living on the embankments. They immigrated to the locality while they thought there were opportunities for fishing in Sundarbans and receiving support from the ongoing governmental and nongovernmental rehabilitation projects. Some emigrants in this SES sought to hide themselves from the legal authorities in Padmapukur village, which is not easily accessible from the local police station. They could therefore live comfortably here while fishing in Sundarbans or nearby rivers. No other immigrant families were reported in discussions with the other four studied villages.

3.3.3. Gender Dimensions

It is mainly the male population who migrate seasonally, with hardly any female examples reported in the discussions. The reasons are threefold: (i) women take care of family members and household activities, (ii) accommodation in migrant destinations is insecure and women are exposed to sexual harassment, and (iii) women are paid less in almost all sectors of employment. Women who are forced to work outside their families usually work within their communities, mainly in fish-larva collection, earth-work for road reconstruction, as factory labour, or exceptionally as maid-servants. Women from the Panchkori village (irrigated-agriculture SES) used in particular to work in the cement and Bidi factories in Nowapara municipality, whereas the women in Shovna village (rain-fed agriculture SES) mostly worked as maid-servants (if required). Again, women living in the mangrove-dependent SES collected fish larva (prawn and shrimp) in the rivers and were also employed in earth-work for reconstruction of the embankment and roads in their locality. Some girls in this area went to Dhaka to work in garment production. Women living in the border communities (Chakdah village) were involved in peddling Indian textiles and ornaments in nearby villages. Hardly any of them practiced seasonal or temporary migration. In addition, the discussants mentioned cultural and religious customs and obligations that could not be maintained after migration as one of the major issues preventing women and family members from migrating.

3.4. Livelihood Resilience–Migration–SES

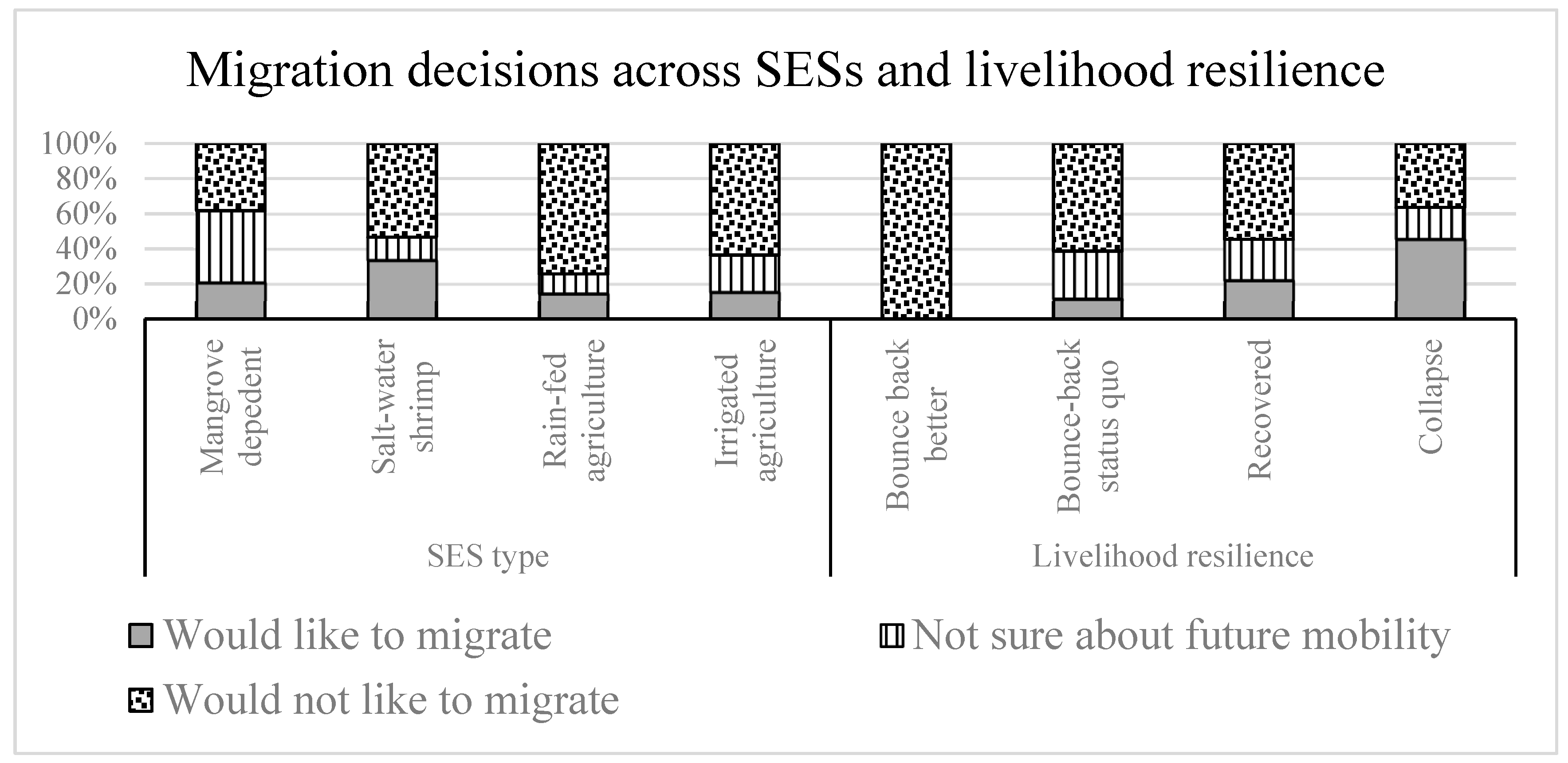

Findings show that, overall, one in five of the discussants would like to migrate from their communities in the near future.

Figure 5 shows that resilient people (bounce back better) are less likely to migrate in the future, whereas among all other categories of livelihood resilience, a majority of the collapsed category intended to migrate in the near future. The majority of people living in salt-water-shrimp-dependent SESs intended to migrate in the future. The studied villages can be ranked according to aspiration for future migration thus: Chakdah → Padmapukur → Vabanipur → Panchkori → Shovna, i.e., the majority of people living in Chakdah village aspire to migrate in the near future. Not only SES characteristics, but also the proximity to India, plays a vital role in their migration decisions.

Most people in this village want to migrate to India, whereas a much smaller number of respondents in the other four villages wanted the same. They mostly favoured migration to the nearby cities and villages, where they will face fewer hazards while enjoying more income opportunities. The result is that people who are mostly dependent on mangrove-forest and shrimp farming were less resilient and would like to migrate in the near future, whereas people living in rain-fed or irrigated-agriculture SESs were more confident of not migrating.

The findings show that most of the people consulted have experienced climatic events constantly from a very early age, and are mostly used to coping with them. They therefore really do not think much about extreme events and are even unworried about climate change and climate migration. Dependency on natural resources is another reason behind non-migration. Land is something on which people depend, and on which people live. People who own land believe that if they migrate to other areas, they will have nobody to guard their land, and subsequently decide not to migrate. This finding supports the concept of ‘place attachment’ [

22,

34,

35]. Moreover, these people usually have social decision-making power. Being affluent, they used to maintain a patron–client relationship within their communities [

36]. They help poor families in difficult times, strengthening their communal ties and social protection, and inhibiting their willingness to migrate. In addition, greater rice production, less conflict, and social connectedness play vital roles in diversifying livelihood and reduce the ratio of poor people in the community, which ultimately helps to keep people in their place of origin.

3.5. Future (Non)Migration: Aspiration vs. Capability

Aspirations to migrate do not always ensure that people can realize their migration. Non-migrants can therefore be categorized into two groups: one group that has the capability to migrate but chooses not to migrate, and another group who are unable to realize migration due to constraints in resources (economic, social, and cultural). The latter is termed a ‘trapped population’ in the literature [

22,

24,

35,

36,

37,

38]. The aspiration to migrate and its realization thus depend on the level of livelihood resilience, which is also characterized by opportunities offered in the respective SES.

While discussing their capability to realize future migration, most of those living in rice-fed agriculture and irrigated-agriculture SESs were confident that they could accomplish their migration desires if it were required of them. In the case of mangrove-dependent SESs, a large number of people reported their inability to emigrate from their community. The reasons mentioned were: (i) most of them are usually living from hand to mouth, (ii) most of them depend on natural resources and therefore cannot save enough to support themselves in a future crisis, (iii) they were living in very remote places, and the cost of migration would therefore be beyond their capacity, and (iv) most of them had nobody in the destination places who can help them to obtain work opportunities or find housing facilities to live in. Most of those living in a salt-water shrimp SES also thought themselves unable to realize their migration aspirations. The reasons for their inability are almost the same as the people living in mangrove-dependent SESs, except that they have an additional problem related to ongoing tensions on the border between India and Bangladesh. Because most of the people in this SES are involved in illegal export–import activities, they have to bribe border police in both countries, reducing the margin on their profit, with the result that they were ultimately unable to save enough to handle future shocks. They had even had to face police harassment several times a year, which also incurred substantial monetary losses. Some families left this village permanently due to continuous harassment by the police, border security, and local politicians, leaving resources and houses behind unsold. In every studied SES, some people were unconvinced about their ability for future migration, as they did not know to where they could migrate permanently together with their whole family.

5. Conclusions

Overall, an SES is a complex system that integrates both nature and people. The dynamic characteristics of an SES shape the overall livelihood strategies of individuals living within it. Usually, every individual tries to improve their quality of life and adopts strategies that help to cope with adverse situations facing their livelihood. Deciding to migrate or not to migrate is one such livelihood strategy to combat unexpected disturbances to one’s normal life.

Again, the study finds that seasonal and circular migration are methods for deciding long-term non-migration from the place of origin. This has been addressed as ‘trans-local’ livelihood in other research [

46,

47,

48]. Non-migration in the face of translocal livelihood explains the situation of a society in which some people regularly or seasonally migrate for principally economic purposes. Such family-member seasonal or translocal mobility builds the household’s capacity to cope in the face of an adverse livelihood situation [

47,

48,

49]. However, it remains unexplored how such translocal mobility of household members contributes to the long-term non-migration of other members of the household, and how it reduces the household vulnerability in general as well as constituting the overall ‘livelihood resilience’ of the household across SESs.

It was evident that most permanent migration occurred due to socio-political conflicts rather than environmental problems, which raises the importance of promoting good governance and human-rights programs. Findings suggest that permanent migration is not a solution for sustainable development; it is rather more important to promote and implement development programmes that will be accepted by local people [

50]. This paper thus indicates that the locational suitability of an SES plays a vital role in the economic progress of a community. Mangrove-dependent SESs, for instance, were not successful enough to recover losses incurred due to cyclone Aila. The ability to migrate is therefore not only dependent on economic capability, but also on the socio-ecological context of the place in which people live.

Furthermore, the historical pattern of migration and livelihood sources also influence future migration dynamics, where the SES characteristics and local political environment play vital roles requiring more detailed research. Findings also indicate variation by gender regarding migration decisions across the SESs, which is another aspect that requires further investigation, taking social norms, culture, and livelihood into consideration.

Finally, given the role of SES and livelihood resilience in migration discussion as presented in

Section 3.3, this study recommends that the climate change adaptation policies should seek to reduce the livelihood vulnerability and improve the well-being of the people living at risk. In the context of the studied SESs, it includes: (i) promoting agricultural adaptation (i.e., conversion from shrimp to rice production) to reduce the livelihood stresses which drive migration; (ii) creating alternative livelihood options, (i.e., establishment of local industries) to enhance resilience and adaptive capacities of the households. It can be done by skill development training, particularly for the women and older people, to improve the likelihood of decent working opportunities; and (iii) finally, enhancing community cohesion by improving the risk-management capacity of the community and voluntary organizations, social groups, and associations.

The methodological approach and conceptual framework used in this research can be employed in different regions sharing similar socio-environmental characteristics, providing an added value to the understanding the interrelationship between migration, livelihood resilience, and socio-ecological systems.