Abstract

The sustainability of rural development, both economic and environmental, has been increasingly linking to local food, which plays an indispensable role by preserving traditional culture, attracting tourists, and supporting the regional economy. However, the authenticity and quality of local food have not been fully convinced as competitive advantages by most practitioners. Little is known about how authenticity affects quality attributes, tourist satisfaction, and tourist loyalty. Thus, this study examines the role of authenticity in the quality–satisfaction–loyalty framework. The field research was performed in Shunde County, Guangdong Province, China. The results challenge the traditional view of quality attributes by highlighting that authenticity is a key antecedent to the quality–satisfaction–loyalty framework of food tourism. In contrast, the relationships among quality attributes, tourist satisfaction, and tourist loyalty are contingent on the extent to which food tourists perceive the authenticity of rural local food.

1. Introduction

Local food is frequently defined as authentic products which not only symbolize tourism destinations but also vividly demonstrate local traditional culture [1]. Nowadays, the sustainability of rural development, both economic and environmental, has been more and more linked to local food [1,2]. Local food has been found to be a key component of the tourism experience and a very important part of the tourism system. It not only stimulates agricultural activity, creates job opportunities, and encourages entrepreneurship, it also enhances destination attractiveness, reinforces destination brand identity, and builds community pride pertaining to food and related culture [3,4,5,6]. Nearly one-third of tourist’s total expenditure is about food, which constitutes a considerable proportion of a destination’s tourism revenue [7]. Local food handed down from one generation to another can also be considered as a condensed representation of the lifestyle and cultural spirit of the local people. Therefore, local food and cuisine have been regarded as strategic tools to promote the social and economic development of destinations [8,9]. Specifically, tourists’ consumption of local food reduces the carbon footprint of food transport and often results in the economic, cultural, and environmental sustainability of rural destinations, which is beneficial for both residents and tourists [1,7]. Local food also provides an authentic cultural experience for tourists, which could lead to a kind of “peak touristic experience” [10]. Moreover, local food is one of the most important motivators for tourists to travel to a particular destination [11]. Food tourism could revive regional gastronomies, food heritage, and special foodways, which, in turn, enhance residents’ community pride and tourists’ authentic experience [12]. Therefore, more and more rural tourism destinations are encouraging the revitalization and promotion of local food for cultural recognition and market exploration.

A lot of academic terms are used to discuss food in tourism. These include ‘culinary tourism,’ ‘food tourism,’ and ‘gastronomic tourism,’ all of which are often used interchangeably in many occasions because of their similar meanings [13]. However, most studies adopt Hall and Sharples’ definition, which defined food tourism as the “visitation to primary and secondary food producers, food festivals, restaurants, and specific locations for which food tasting and/or experiencing the attributes of specialist food production region are the primary motivating factor for travel” [7] (p. 10). This indicates food tourists’ activities are mainly food tasting, farm tours, and wine trails, which are motivated by a desire to experience a certain kind of local food [14]. As a cultural and anthropological concept [13], food is regarded as a metaphor for a construct which could express cultural identity and ethnicity. In return for this, tourists often connect food and eating to rituals, symbols, and belief systems. Therefore, food tourism provides an indispensable avenue for tourists to search for authenticity by perceiving history, tradition, locality, and the uniqueness of local food and food heritage.

Despite the importance of local food for rural sustainability, tourists’ food consumption is often regarded as a sort of paradox of which there are both obligatory and symbolic facets [15]. The former, obligatory facet means people must eat while traveling, while the latter, symbolic facet, includes not only gaining sensory pleasure but exploring local culture and questing for authenticity. In their latest publication, which answered the question of what food tourism is, Ellis, Park, Kim, and Yeoman pointed out that food-tasting is a kind of cultural experience, and authenticity is of paramount importance [13]. Obviously, this shows that authenticity is one of the dominant attributes for food tourism [1]. As for food tourists, much of the appeal of local food lies in the fact that it is special and unique. Thus, the best way to experience food authenticity is to be there. Consequently, one of the most important aspects of food tourism experience is authenticity [13]. Tasting local food is an indispensable way to quest for authenticity for tourists.

Current research emphasizes that food authenticity should be an antecedent of tourism experience and satisfaction [16,17,18]. Along with authenticity, quality attributes of food tourism, such as food, service, and the physical environment, are also crucial for tourists’ food consumption experience [19,20,21]. Local restaurants are mediums of tourists and local cuisine [5]. Local food is presented in suitable ways by restaurants so that tourists can accept local food. Accordingly, food tourists are supposed to use three types of quality attributes to judge their gastronomic experience [21,22]: Functional—food quality; humanic—service quality; and mechanical—the physical environment [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Moreover, traditional cooking needs to connect with modern consumers; therefore, quality attributes should be considered to make tourists satisfied and loyal [22]. However, the effects of food authenticity and quality attributes are not clear [5,31]. A tourism dining experience can be distinguished into “supporting the consumer experience” and a “peak touristic experience” [32]. The former shows the importance of the quality attributes of local food, while the latter shows that authenticity is essential for tourists. Obviously, authenticity and quality are indispensable for the tourist food experience. However, little research has addressed the combined effects of quality attributes and food authenticity on tourist satisfaction and behavioral intentions.

To fill these research gaps, the purpose of this study is to explore the role of authenticity in the quality–satisfaction–loyalty framework. To achieve this objective, Shunde County, one of the creative cities of gastronomy identified by UNESCO [33], was chosen as the site of this research. Located at the core of the Pearl River Delta, Shunde is well-known for its Cantonese cuisine and gastronomical cultural industries. Our findings support the proposition that a high level of authenticity leads to high quality attributes of food tourism, which lead to high tourist satisfaction and tourist loyalty. The major contribution of this study is that it may offer managerial guidelines and feasible approaches to improve local food quality and authenticity and then create a satisfactory tourism experience that enhances tourist loyalty to rural destinations. The focus of this study is to investigate the tourist consumption of authentic local food in an attempt to generate a holistic view of the authenticity and quality attributes of local food, as well as tourist loyalty to tourism destinations. Our research is beneficial for tourism destinations intending to create authentic food experiences, which in turn create a sustainable tourism experience for tourists.

This article is organized as follows. In Section 2, there is an intensive literature review on food authenticity, the quality attributes of food tasting, tourist satisfaction, and loyalty, all of which lead to twelve research hypotheses. Section 3 analyses the local food and culinary tourism offered in the city of Shunde, China, and then describes the methodology we used. In Section 4, we provide the research results in which nine hypotheses are supported. Then, we discussed the research results in Section 5. Finally, the conclusions and implications of our research in Section 6. Finally, the limitations of our research and recommendations for future research are discussed in Section 7.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Authencitiy of Local Food

The typical meaning of authenticity is the genuineness, honesty, or sincerity of an object [34]. McConnell firstly introduced authenticity and proposed the theory of “staged authenticity,” in which authenticity is an inherent property of the tourism object and obtaining authenticity experience is regarded as the fundamental goal of tourists, into tourism research [35]. Furthermore, Wang divided the concept of “authenticity” into four main schools: Objectivism, constructivism, postmodernism, and existentialism [36]. Objective authenticity emphasizes the authenticity of the objects visited by tourists. Constructive authenticity is the result of a social construction rather than objective things. This is the authenticity that a tourist or a travel producer projects on a target in accordance with its imagination, expectations, preferences, beliefs, and abilities. Therefore, the same object will form a different authentic experience, and the authenticity of an object is its symbolic authenticity [37]. The authenticity of postmodernism raises the concept of “super-reality.” Culture itself is constantly changing and constantly creating new content. Existentialists emphasize the subjective experience of tourists rather than the authenticity of tourist objects. Therefore, existential authenticity can be called an “authentically good time” [36,38]. This means existence authenticity refers to a potential state of life that requires tourism activities to activate.

Food authenticity could be regarded as the genuineness of local food which is specific to a place and a kind of description of local culture. Authenticity is one of the most important aspects of the food tourism experience [13]. An authentic food experience is a kind of cultural phenomenon in which chefs, restaurants, recipes, and dishes are considered in ways that allow visitors to integrate into the local culture and spirit [1,9]. Authenticity being embedded in cooking methods and unique foodways is a key motive for food tourists [1,12]. As an expression of destination cultural attractions, local food demonstrates traditions, legends, stories, and symbols, which, in turn, closely bind local food with authenticity. Tasting local food is a convenient way to explore local culture [10] and could provide tourists with clues about what local people eat, how they prepare their food, and how the local food tastes. This sensory cultural exploration makes tourist experience feel authentic. Therefore, local food is one of the objects that conveys authenticity and a sensory expression of local culture and tradition, which could be a kind of resource for tourists seeking such authenticity in their experiences [39,40,41]. This means that authenticity is one of the most important motivations for tourists to travel [42,43]. For tourists’ food experience, authenticity is even more significant because tourists perceive authenticity in the process of gazing, smelling, listening, and tasting.

Local food, usually traditional, is a tool for tourists questing for authenticity [1]. There are three contexts, depending on the extent of tourist’ quest for food authenticity [44]. In the first context, tourists prefer pure local food, producers, servers, and physical environments in order to experience objective, constructive, and existential authenticity, all of which leads to a sort of peak touristic experience. These tourists prefer local restaurants operated and visited by residents. Interestingly, tourists in the second context are willing to taste food blended with both familiar and unfamiliar cultural attributes. In this way, they have a sort of temporary peak experience. These tourists are concerned with staged authenticity and patron restaurants with local food, familiar services, and a familiar environment. In contrast, tourists in the third context are in an environmental bubble in which they only have a sort of supportive food experience. They prefer all-inclusive resort hotels and restaurant chains, which makes their food consumption in holidays an extension of their daily lives. Obviously, on this occasion, quality attributes—food quality, service quality, and the physical environment—are important.

Authenticity could be viewed as ‘unique’ and could therefore encourage tourists to specifically visit such tourism destinations and have a satisfactory experience [12]. Authenticity in food consumption includes the authenticity of both the food experience and restaurant experience [44]. Food authenticity includes cooking methods, cooking odors, recipes, ingredients, food and drink customs, social connotations, related ceremonies and festivals, and hunting and farming traditions [1,45]. For example, the authenticity of local Indonesian food is reflected by authentic taste, a true level of spiciness, unique cooking methods, and eating methods . The decoration and layout of dining facilities could also show the authenticity of local food [17]. In addition, Hall proposed that, if the appearance of the service provider corresponds to the ethnic background of the restaurant, the customer will feel that the food, employees, and culture of the ethnic restaurant are more authentic [46]. Furthermore, the appearance of restaurant staffs serves as a tangible clue and becomes an important source of the customer perception of authenticity [47]. Tasting authentic local food leads to the tourists’ cultural exploration of their tourism destination, which is an experiential way for tourists to percept a new different culture. A good food experience helps to increase the attractiveness of the destination, increasing visitor satisfaction and revisit intention [5]. Furthermore, perceived authenticity influences perceived quality and satisfaction [48]. According to Wijaya et al., the tourist dining expectations of local food include seven factors: Staff quality, sensory appeal, food uniqueness, local servicescape, food authenticity, food familiarity, and food variety [49]. This shows that tourist dining expectations involve food authenticity, food quality, food service, and the physical environment, the fulfillment of which could possibly lead to tourist satisfaction with the local food experience.

Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The authenticity of local food has a positive and direct effect on food quality.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The authenticity of local food has a positive and direct effect on service quality.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The authenticity of local food has a positive and direct effect on the physical environment.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The authenticity of local food has a positive and direct effect on tourist satisfaction.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The authenticity of local food has a positive and direct effect on tourist loyalty.

2.2. Quality Attributes of Local Food Tasting

Tourists perceive restaurants as an important attribute of a tourist destination, one whose food quality, food service, and physical environment could show local traditions and culture and then shape the tourist gastronomy experience [50]. They are often enthusiastic about tasting the local food of tourism destinations despite its differences with their familiar food in terms of product characteristics, social features, and ecological features [51]. Furthermore, the tourist experience of local food often happens in tourism destinations where dining plays a stronger social function amongst tourists, tourism service personnel, and the local community [52]. This shows that the quality attributes of tourist food experience include not only food quality but service quality and the physical environment [3,19]. Customers evaluate their consumption experience at the attribute level rather than the product level [23,53]. Therefore, the tourist perception of quality could be evaluated from an attribute-based approach, which measures food quality, service quality, and the physical environment.

As the core product of commercial food service, food quality plays a pivotal role in the dining experience and is critical to the success of the restaurants at tourism destinations [21,54]. In fact, food quality, service quality, and the physical environment are major factors influencing customer satisfaction with a dining experience and key determinants of a customer’s choice of restaurant and re-visitation [23,55,56,57]. At the same time, many scholars have described various attributes that constitute food quality.

The service quality of a local food dining experience plays an important role in the whole tourism experience. It stems from the customer evaluation of the gap between their expectation and perception of their service [58]. Therefore, service quality is not only a subjective concept but also a comparative gap between the expectations of tourists and the actual acceptance of services [59]. In the catering industry, service quality has been proven to be one of the core attributes that leads to customer satisfaction and customer choice of restaurants [21,23]. Improving the quality of catering services could enhance customer satisfaction and loyalty, and it could maintain customers’ stability [48]. These show that service quality is a customer’s judgment of the overall excellence or superiority of the service.

The physical environment is an important factor which should be considered when tourists assess the service delivery of dining experience. To the authors’ best knowledge, Kotler is the first scholar to use the concept of “atmosphere” to define the physical environment as a design of space to create certain effects in consumers [60]. Other research, such as Bitner, used “servicescape,” which means a man-made environment for consumers, to describe the physical environment [61]. The physical environment is especially important in the catering industry for creating images and influencing customer behavior.

Despite food quality being the most important determinant of dining satisfaction and loyalty, both the physical environment and service quality (e.g., fairness of seating procedures) are important to customer satisfaction [62]. In fact, culinary tourists’ satisfaction is influenced mainly by four factors, including food quality, service quality, the physical environment, and price [63]. According to Liu and Tse [64], four factors—food, service, the physical environment, and customer value—are positively and directly related, not only to dining satisfaction but to behavioral intentions. To date, recent studies have shown that food quality (e.g., taste, healthy, freshness, and safety) and the physical environment (e.g., cleanliness) are the strongest predictors of customer satisfaction and behavioral intention [65,66]. Using online customer reviews and data mining techniques, Bilgihan, Seo, and Chio found that three main clues—food, the physical environment, and service—could explain dining satisfaction [28]. Based on the expectancy disconfirmation theory, Weiss, Feinstein, and Dalbor found that four factors, including food quality, service quality, the physical environment, and novelty, are determinants of dining satisfaction, while only food quality and atmosphere are significant attributes for influencing behavioral intention [67]. Lin and Mattila also found that the physical environment and service quality have direct positive influence on dining satisfaction [68].

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Food quality has a positive and direct impact on tourist satisfaction.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Food quality has a positive and direct impact on tourist loyalty.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Service quality has a positive and direct impact on tourist satisfaction.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Service quality has a positive and direct impact on tourist loyalty.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

The physical environment has a positive and direct impact on tourist satisfaction.

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

The physical environment has a positive and direct impact on tourist loyalty.

2.3. Tourist Satisfaction and Loyalty

Customer satisfaction is one of the important concepts in the field of consumption. Oliver found that customer satisfaction is a state of mind and an emotional response to the consumption process [69]. Fornell believed that satisfaction is the overall attitude of customers after consumption and could show how much customers like their consumption process [70]. These indicate that customer satisfaction is an assessment of the difference between a customer’s pre-consumption expectations and their perceived perceptions after consumption [71]. If the actual performance perception is higher than expected, customer satisfaction is generated. Otherwise, the customer is not satisfied. In tourism research, tourist satisfaction is used to measure the feelings of tourists about tourism activities. For example, Pizam, Neumann, and Reichel argued that tourist satisfaction is the result of a comparison between tourists’ experiences and their expectation of a tourism attraction [72]. If the level of travel experience is higher than the expected value of the destination, the visitor is satisfied. Therefore, this study regards tourist satisfaction as the difference between the expectation value of tourists’ tourism activities and their perception of its actual performance.

Tourist satisfaction is essential to the success of tourism activities. High levels of customer satisfaction are a major concern for all companies [73]. Numerous studies have investigated the role of tourist satisfaction in travel literature. For example, Girish and Chen concluded that tourist satisfaction significantly affects their willingness to revisit and the intention to recommend [74]. Tanford and Jung found that tourist satisfaction has a significant positive impact on tourist loyalty [75]. Furthermore, Chen and Rahman argued that visitor satisfaction is crucial for successful destination marketing because it affects the choice of destination, the consumption of products and services, and the decision to return [76].

Establishing and maintaining a loyalty relationship with consumers is often considered to be a good strategy for business success. Oppermann believes that the loyalty of tourists is mainly manifested in the willingness of tourists to revisit the destination and the willingness to recommend the destination to others [77]. Backman and Crompton combined both the behavior and attitude of tourists, believing that loyalty is expressed as the frequency of visitors’ participation in activities, purchase of products or services, and emotional preferences for products or services [78]. Zeithaml, Berry, and Parasuraman argued that consumer loyalty includes consumer verbal praise and a willingness to revisit [58]. Based on the above viewpoints, this study summarizes tourist loyalty as the willingness of tourists to praise, the willingness of tourists to revisit, and the willingness of tourists to recommend. This study can then comprehensively measure the loyalty of tourists from these three aspects.

Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

Tourist satisfaction has a positive and direct impact on tourist loyalty.

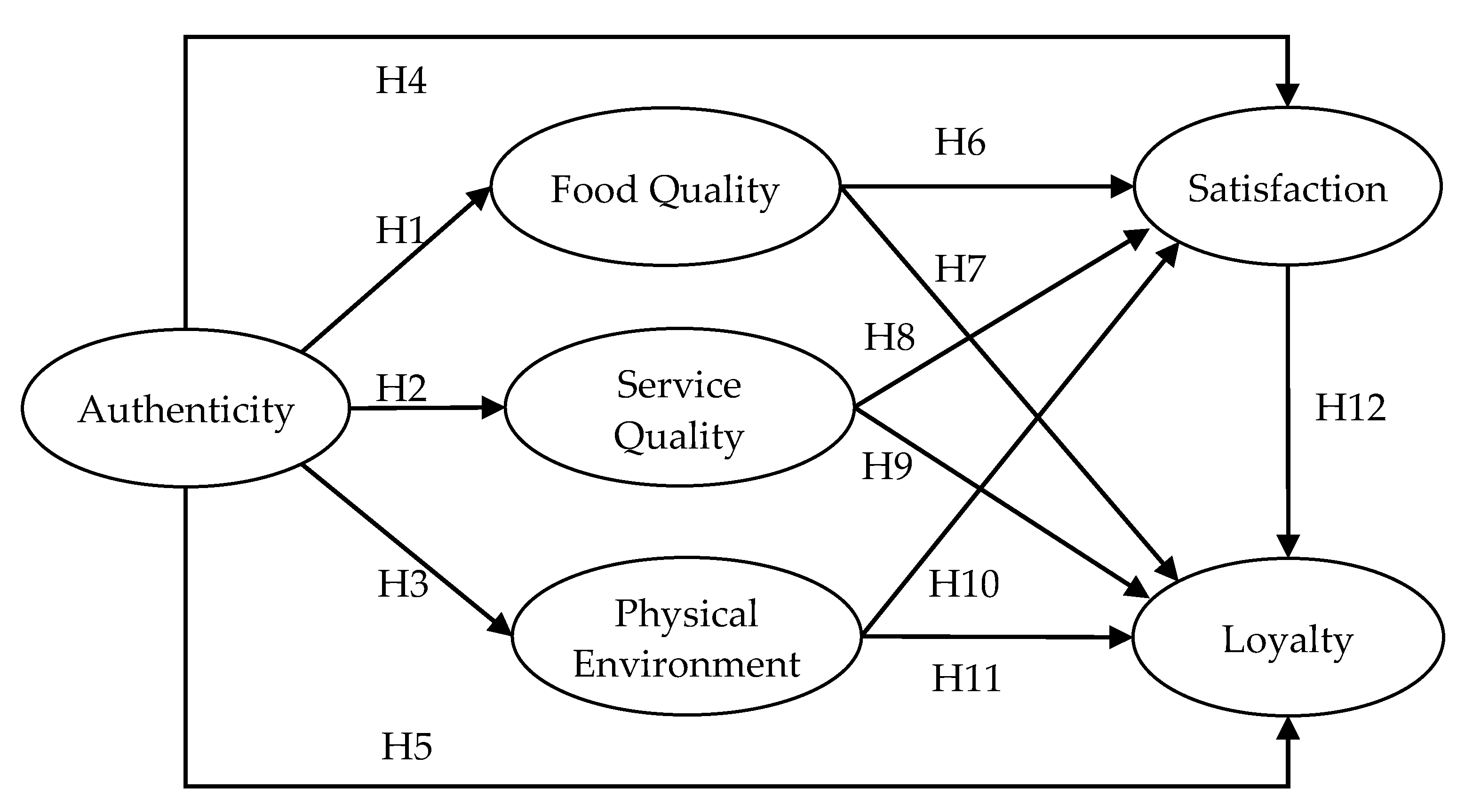

Drawing on the above literature review and the above hypotheses, this study proposes the theoretical model shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The theoretical model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

The investigation was carried out at Shunde County, a county in the south of Guangdong Province, China, which is well-known for food culture and various delicious foods. Shunde is also famous for its gastronomical cultural industries and the World Food Capital awarded by UNESCO [33]. In Shunde, there is a town named Jun’an which has a well-known traditional cuisine—Jun’an steamed pork. This cuisine became popular for tourists after the documentary “A Bite of China” was broadcast in 2012. Visitors who tasted the Jun’an steamed pork were invited to participate in a survey under the guidance of a researcher. First, 130 initial questionnaires were issued in November 2018. The obtained data were used to analyze validity in order to improv the questionnaire. Then, 500 formal questionnaires were issued in January 2019. 520 questionnaires were distributed to the tourists, and 471 completed questionnaires were received, among which 24 were incomplete. Finally, 447 usable questionnaires were received, resulting in an 86% effective response rate.

3.2. Measurement Instrument

We designed a self-administered questionnaire to collect empirical data. The survey instrument was firstly designed by interviewing tourists who had visited Jun’an (see Appendix A). Secondly, a comprehensive literature review was performed to develop the final questionnaire. The questionnaire mainly consisted of two parts. The first part included the questions for measuring food authenticity, the quality attributes of local food, tourist satisfaction, and loyalty. The second part consisted of questions about respondents’ demographic characteristics. All items in the first part needed to be answered to rate the significance on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

The items of the measurement instrument were adopted from previous research (see Appendix B). Food authenticity was measured by 9 items: Local ingredients (A1), unique cooking methods (A2), local taste (A3), special kitchenware (A4), local food (A5), time-honored catering (A6), local food culture (A7), local eating habits (A8), and eating with residents (A9), which were adopted from previous research [17,44,45,49,59,79]. Food quality was measured by using five items: Deliciousness (F1), nutrition (F2), attractive smell (F3), fresh food (F4), and suitable temperature of food (F5), which were adopted from previous research [23,56,57,80,81,82]. Service quality was measured by 4 items: Concern and help (Q1), quick response (Q2), various services (Q3), and respect for customers (Q4), which were adopted from previous research [21,49]. The physical environment was measured by 4 items: Convenient parking and transportation (P1), lighting (P2), temperature (P3), and comfortable seating and space (P4), which were adopted from previous research [57,83,84]. Tourist satisfaction was measured by 5 items: Overall satisfaction (S1), satisfactory value for money (S2), enjoyable food experience (S3), the feeling of receiving what one had wanted (S4), and the exceeding of one’s expectations (S5), which were adopted from previous research [48,55]. Tourist loyalty was measured by 3 items: Re-patronage intention (L1), positive word of mouth (L2), and recommendation (L3), which were adopted from previous research [48,55]. The survey questionnaire included 25 questions and took 5–8 minutes for participants to complete.

3.3. Reliability and Validity of Measurement Scales

This study assessed the reliability and validity of the measurement instrument by using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), respectively. As shown in Table 1, all the values of Cronbach’s alpha were between 0.885 and 0.944, greater than the threshold of 0.7, which suggests that the scales had a reasonable reliability. The composite reliability (CR) was between 0.891 and 0.946, above the 0.6 level. The squared multiple correlations (SMC) were between 0.44 and 0.88, and almost all scores exceeded 0.5. These scores suggest an acceptable reliability. All the fit indices were within the recommended thresholds, which indicates an acceptable fit.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity of measurement scales.

We used validity test to examine the extent to which a scale truly measures a construct of interest, including convergent and discriminant validity. The standardized factor loading of all items exceeded all thresholds, which supports the convergent validity of the measurement scales. The average variance extracted (AVE) represents the comprehensive explanatory ability of potential variables to all measured variables. The convergent validity test can be passed if the factor loadings are above the threshold of 0.7 and AVE is above the threshold of 0.5. All constructs showed a satisfactory convergent validity, as factor loadings ranged from 0.66 to 0.94, and most AVE values (which are statistically significant at 0.001) were larger than 0.5. Thus, the reliability and validity of the scales were supported.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Charisteristic of Respondents

Among the 447 respondents, 51% were female, and 49% were male. In terms of age, 69.1% of the respondents were between 21 and 35 years old, 20.6% were between 36 and 50, 4.7% were between 51 and 65, 4.5% were under 20 years old, and 1.1% were above 65 years old. 73.6% of the respondents had a college degree, followed by high school degree (12.8%), master’s degree (9.2%), and the other (4.5%). 43.4% of the respondents had a personal monthly income between 4000 and 8000 CNY, followed by 8000–12,000 (19.9%), less than 4000 (18.1%), 12,000–16,000 (9.6%), and higher than 16,000 (9.0%).

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

The results of descriptive statistics of all constructs are shown in Table 2, and they include means and standard deviations (SD). The values of the means of all constructs exceeded the mid-scale point of 3. The physical environment had the highest mean (PE = 5.70), followed by food authenticity (FA = 5.65), tourist satisfaction (SAT = 5.43), service quality (SQ = 5.43), tourist loyalty (LOY = 5.37), and food quality (FQ = 5.35). The results of a Pearson correlation analysis ranged from 0.526 to 0.817 and was significant at the 0.01 level, which shows that there are significant correlations among these constructs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

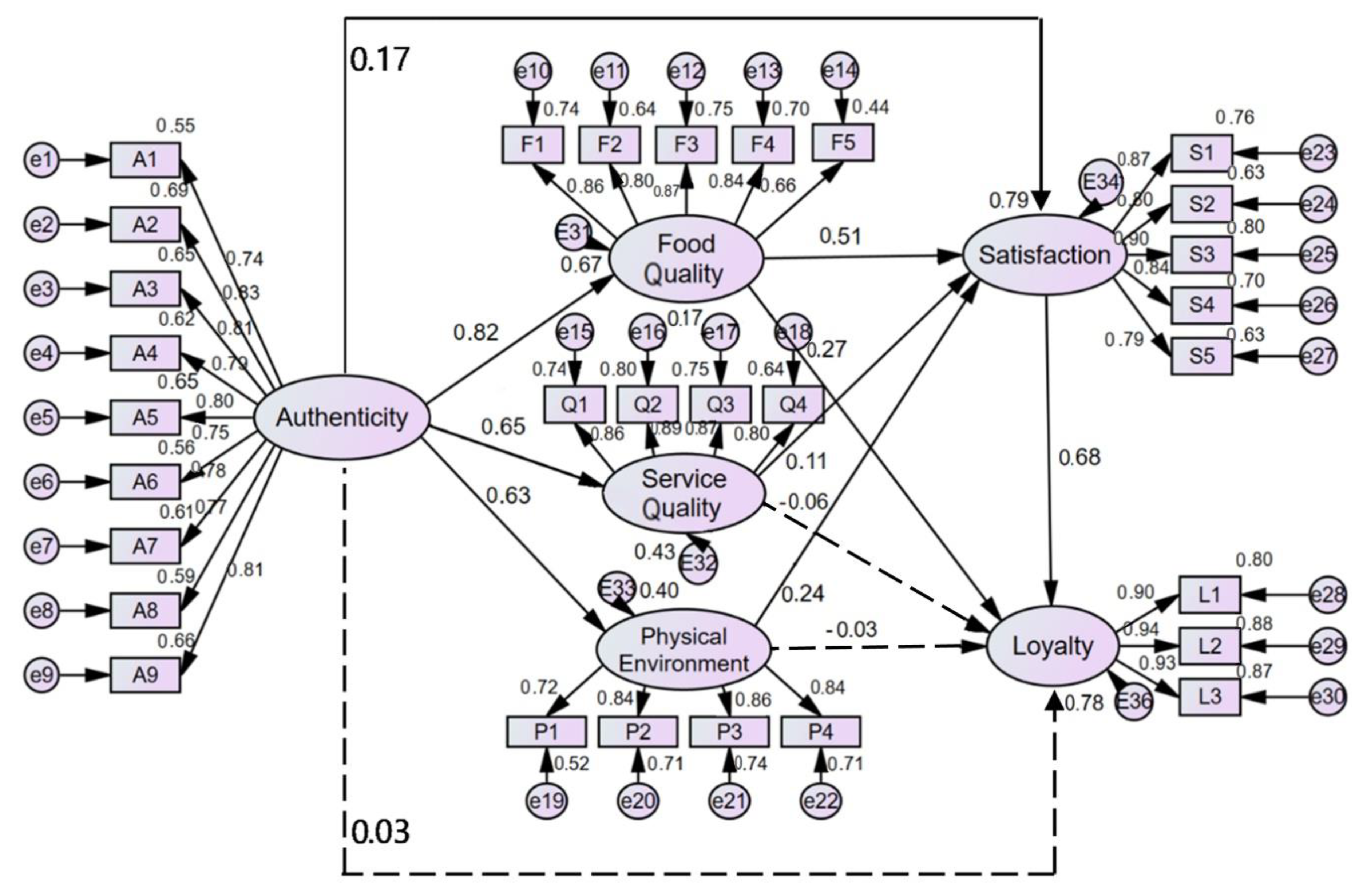

A path analysis using AMOS 21 was performed to test the hypotheses (see Figure 2). The results show that = 1157.879; degrees of freedom = 393; p < 0.000; /df = 2.946 (less than 3); CFI = 0.935, IFI = 0.936 and TLI = 0.928 (both are greater than 0.9, thus reaching acceptable levels); GFI is 0.847, slightly below 0.9; and RMSEA = 0.066 (less than 0.08), indicating that the research model fits well with the data. Given that all the fit indices were within conventional cutoff values, the model was deemed acceptable.

Figure 2.

The results of the AMOS output.

The relationships proposed in the model were examined next. The significant factor load is an important indicator of a model measurement of polymerization validity. If the absolute value of T is greater than 1.96 and if p < 0.05, the path is acceptable. As shown in Table 3, the results reveal the positive and direct influence of food authenticity on food quality (r1 = 0.82, t-value = 13.05, p < 0.05), service quality (r2 = 0.65, t-value = 13.27, p < 0.05), the physical environment (r3 = 0.63, t-value = 12.48, p < 0.05), and satisfaction (r4 = 0.17, t-value = 2.74, p < 0.05). Food quality had a positive and direct effect on tourist satisfaction (r6 = 0.51, t-value = 8.05, p < 0.05) and tourist loyalty (r7 = 0.28, t-value = 3.74, p < 0.05). Service quality had a positive and direct effect on tourist satisfaction (r8 = 0.10, t-value = 2.57, p < 0.05). The physical environment significantly affected satisfaction (r10 = 0.24, t-value = 5.83, p < 0.05). Finally, tourist satisfaction positively influenced tourist loyalty (r12 = 0.63, t-value = 8.92, p < 0.05). Thus, H1, H2, H3, H4, H6, H7, H8, H10, and H12 were supported (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Hypotheses testing.

5. Discussion

These days, commodifying food culture and culinary heritage as meal adventures has become a popular approach to attract food tourists [11]. For example, La Boqueria Market in Barcelona, Spain, attracts tourists because it gives them the sense of escape from routine, cultural experience, prestige, and the flow shopping experience [85]. Undoubtedly, local food is an essential element for sustainable tourism and one of the signifiers of the authenticity of local culture. Non-local food in tourism destinations gives tourist an impression that this food is not authentic [10]. Though local food may be totally different to a tourist’s daily food [51], it could fulfill a visitor’s quest for authenticity. According to Quan and Wang [32], a primary tourism motivation usually results in a peak consumption experience. Therefore, food tourists’ food experience is not a supportive experience, but it is a peak experience. This means that food authenticity is essential for them because modern consumers desire authentic experiences [86]. According to Özdemir and Seyitoğlu [44], there is a continuum of tourists’ questing for food authenticity. Two extreme contexts emerge from this continuum: On the left edge, tourists search for experiential authenticity with a strong desire for experiencing food authenticity. On the right edge, tourists search for safety and comfort with a strong tendency to enjoy unauthentic but familiar and safe food. Between the left and right edges of the authentic continuum, staged authenticity is the context for which most tourists quest. These tourists tend to accept certain levels of risk and novelty This means they might enjoy blended food culture, familiar attributes, and restaurants with an authentic atmosphere.

According to the results, the path coefficient of food quality to loyalty is 0.28, which has a positive effect. Conversely, H9 and H11 were rejected, which indicates that service quality and environmental quality may have no significant impact on loyalty. In particular, food quality has proven to be the biggest contributor to authenticity, and delicious food is often seen as a key factor in customer satisfaction and repeat visit decisions in the context of authentic Chinese restaurants [55,87]. Overall, food taste and service reliability appear to be key attributes for Chinese restaurants’ success [84]. Surprisingly, in Chinese restaurants, only the perception of food quality has a positive impact on diners’ loyalty. When the diners decide to return to the restaurant, food quality may be considered the most critical factor; both service quality and environmental quality are independent of revisiting and recommending willingness [55,87]. In addition, in a study of food festivals, only food quality and special facilities directly promoted the willingness to revisit the Slow Food Festival [56].

According to our research, H5 was not supported, which means authenticity has no significant effect on loyalty. The model results show that a pure authentic state does not automatically generate higher tourist loyalty unless it is associated with satisfaction, which may be due to tourists’ personality traits, such as food neophobia [88]. Some scholars believe that tourist satisfaction plays a mediating role in the relationship between authenticity and loyalty [31,89]. Novello and Fernandez [31] proposed that authenticity is experienced outside the boundaries of everyday life, and real experience does not guarantee loyalty, as visitors must assess whether it meets their expectations and personal needs. In gourmet tourism, though tourists perceive authentic food as traditional and characteristic of the local culture, to form customers’ willingness to revisit still requires the consideration personal tastes and habits. For example, in this study, some tourists said that steamed pigs are authentic, but the willingness to revisit was not strong because they are too fatty, not conducive to health, taste too salty, and so on. On the other hand, Engeset and Elvekrokalso have a special explanation for this [89]. When the real concept exists, the guests pay more attention to relevant attributes (food, service, and environment) to form their satisfaction evaluation. Obviously, these positive attitudes towards local food often lead to higher tourist expenditure and a greater appreciation of local food [90], which, in turn, promote a sustainable tourism experience and the sustainable development of tourism destinations.

Many empirical studies have found that tourist satisfaction has a positive impact on loyalty; the more satisfied tourists tend to praise [76], convey positive experiences, and repeatedly purchase [74,91]. In this study, tourist satisfaction played an intermediary role in the impact of authenticity and quality on loyalty. According to our research, a high quality of food, service, and the physical environmental can lead to future favorable behavior and loyalty by improving customer satisfaction. Tourist loyalty is necessary to achieve the success of tourism activities, a success which comes from a good travel experience. It must be recognized that visitor satisfaction is an important factor in loyalty and the willingness to revisit [31]. These positive attitudes lead to tourists’ sustainable tourism experience.

This study confirmed previous related studies, which have shown that authenticity has a positive impact on attribute quality [1,48,89] and satisfaction [17,45,79,92,93]. Food authenticity is an important contribution to the shaping of participants’ dining expectations [49]. If the food experience is perceived as authentic, it is more likely to be perceived as high quality and valuable, and it is also be more likely to satisfy tourists [48]. Interestingly, our research shows that high authenticity of local food would effectively raise various quality attributes, including food quality, service quality, and the physical environment. In return for this, tourists gain positive attitudes towards local food and are impelled to spend more [94]. This profitable result would be beneficial to the sustainable development of tourism destinations and the sustainable tourism experience as well.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study introduces the concept of authenticity and uses empirical research to explore the impact of food tourism authenticity and quality attributes on tourist satisfaction and loyalty. Authenticity should be one of the major concerns when tourists are tasting food in tourism destinations. This means a tourist’s subjective perception may give them a reason to taste local food and to quest for authenticity as well. As an important abstract concept, authenticity may have vague and broad meanings and might signify many things at once.

From the perspective of tourism attractions, local food demonstrates residents’ traditional culture and daily life, provides an authentic experience of traditional culture, and presents rich and imaginative impressions of tourism. Tourists search for authenticity when travelling, and local food provides an opportunity to experience authenticity. The tourist experience of local food includes not only food tasting but also their impressions of dining environment and service. These studies show that a restaurant’s attribute qualities have a positive impact on customer satisfaction and consumer loyalty.

Authenticity and quality attributes are very important for customer satisfaction and loyalty. Local food is a symbol of a place and culture. In fact, local food and cuisine have been indispensable factors of the tourist experience and are often considered the best things to enjoy in tourism destinations [4]. Tourists’ food experiences are different to their daily experiences when they quest for food authenticity. According to our analysis, different tourists have different attitudes to local food. Today, with the rise of the experience economy, tourists have more requirements for travel experiences. Obviously, visitors may be not interested in standardized products but pay more attention to appearance, service, and feelings of dining experience [79].

The roles and effects of local food are increasingly important for the competitiveness of tourism destinations. Tasting local food could satisfy the experiential needs of tourists. These needs include exploring local culture, gaining authentic experiences, and having educational opportunities. Gastronomy is one of the most important factors that affects tourists’ destination choice and activity participation. As tourists hunt for more authentic and local experiences, rural gastronomy has become an effective source to attract tourists, especially city dwellers, to visit. The tourist consumption of rural gastronomy encourages the development of sustainable agritourism, which in turn conservse traditional farming and rural cuisine. The results of this study thus extend previous studies.

This study suggests that catering and food enterprises should strengthen consumers’ perception of objective and subjective authenticity of local food. They should also maintain origin and tradition of time-honored cuisines and highlight the characteristics of inheritance and classics. For gourmet travel, thebasic competitive advantage is high quality food. Maintaining mysterious formulas, the authentic origins of raw materials, etc., can make classic dishes and form a unique reputation. On the other hand, the provision of gourmet food is only the most basic project, and one cannot rely solely on lecture-style exhibition to get visitors involved. Therefore, the production process of a local cuisine could also be a part of a tourist’s authentic experience. In particular, providing atmosphere, tools, and materials could allow visitors to personally experience the unique craftsmanship of the food, to teach the special dining etiquette, to enjoy the fun of hands-on processes, cultivate sentiment, and to deepen their impression of the gourmet tourism. In addition, reflecting the unique cultural style of the local area is a main development direction of gourmet tourism. Linking delicacies to cities gives tourists a reason to experience them. This gives time-honored catering a unique local style, and gourmet tourism can become more colorful and rich in charm.

This study suggests the food tourism organizers focus on food culture and word of mouth. Catering culture and eating habits are the cultural attributes formed by time-honored catering in the development process. They are not available in other fast food restaurants, and they are also intangible parts of authenticity. When a restaurant is developing, it needs to pay attention to the inheritance of brand culture. At the same time, a restaurant must convey the cultural philosophy, as well as the history and traditions of the restaurant to customers in order to increase trust and recognition. On the other hand, authenticity of local food promotes and guides the positive reputation of tourists. The positive word of mouth of tourists has become an intangible value of time-honored catering in gourmet tourism. Word-of-mouth publicity is a traditional and effective strategy of tourism marketing. Tourists recommend and share on social networks. People who have not participated will have an initial impression of the activity based on the photos, insights, or strategies of the sharer, thereby enhancing their desire and motivation to participate. In addition, through social network media marketing, people could recommend local food through their check-in and likes on the internet, by which they share their souvenirs, discounts, and other incentives to stimulate the willingness of visitors to share and recommend. All of this helps marketing and publicity.

To conclude, it is extremely important to protect traditional culinary culture and improve dining quality attributes for practitioners, which, according to our study, are essential ways to authenticate local food. By strengthening the authentication process of local food, this study sets out a theoretical framework for the marketing of local food and the creation of a sustainable tourism experience in rural tourism. This framework is useful for designing the authentication process in order to create a sustainable tourism experience. The authentication process, according to our research model, demonstrates that authenticity could improve food quality, service quality, and the physical environment. In return for this, tourists become satisfied with local food, buy more food, recommend the destination to others, re-visit destinations, and, most importantly, gain a sustainable tourism experience, all of which are extremely helpful for the social, cultural, and economic development of rural tourism destinations.

7. Limitations and Future Research

To the authors’ best knowledge, this study has three main limitations. First, the measurement scale of gastronomic authenticity in this research could be questioned. A comparison of first-time and repeat visitors would useful. Second, a future study is recommended to investigate the difference of authenticity perception between first-time and repeat visitors. Demographic characteristics could also be considered to evaluate the model. According to Robinson [43], food tourists in Australia are mostly female, well-educated, and generally affluent. Third, the case in this study is a kind of Cantonese food, which is familiar to Cantonese people but may be unfamiliar to the tourists from other places in China or other counties. Therefore, more food culture should be studied to test our model.

This study takes time-honored catering as an example to study the authenticity perception of tourists’ gourmet tourism. Due to the profound historical heritage of time-honored catering and its local representativeness and influence, this study provides a certain reference for the development of gourmet tourism for destinations. However, it should be recognized that gourmet tourism is not limited to time-honored catering. Local snack bars, specialty restaurants, folk customs streets, and even gourmet festivals are important research parts of gourmet tourism. .

Author Contributions

T.Z. contributed to research design, data analysis, and whole manuscript writing. J.C. contributed to investigation and data analysis; and B.H. contributed to research design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Macau Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Macau Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

- Why did Jun’an steamed pork could attract your visiting?

- What are the most authentic features or characteristics of Jun’an steamed pork?

- What are the most important of the quality attributes when you are tasting Jun’an steamed pork?

Appendix B

1. Food Authenticity

(1= completely disagree, 2 = disagree; 3 =neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = completely agree)

| (1) Food ingredients are local | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (2) Use authentic cooking methods | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (3) Appearance display is attractive | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (4) Steamed pork has authentic taste | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (5) Restaurant environment with local characteristics | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (6) Production site (a kitchen makes people feel authentic) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (7) The dress of the chef and waiter is the local custom clothing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (8) Special kitchenware (large steamer) makes people feel authentic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (9) Appreciating cooking on the spot makes people feel real | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (10) The historical story described makes people feel authentic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (11) It is a local food | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (12) “Time-honored catering” restaurant makes me feel authentic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (13) Experience the local Shunde food culture | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (14) Can feel the local people’s eating habits | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (15) Tasting in the local area makes people feel authentic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

2. Food quality

| (1) Food is delicious | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (2) Food is nutritious and helps health | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (3) Food smell is very attractive | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (4) Food display is visually appealing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (5) Food is fresh | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (6) Suitable temperature of food | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (7) The restaurant offers a variety of menu options | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

3. Service quality

| (1) Comfortable and tidy service | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (2) Waiters wear proper and clean suits | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (3) Waiters are polite and trustworthy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (4) Waiters fully understand my needs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (5) Waiters showed concern and enthusiasm to help | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (6) Waiters respond to my needs immediately | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (7) Provide various services to meet needs of customers | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (8) Staffs respect customers’ personal needs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (9) Service is fast and efficient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (10) Service could be finished within the time promised | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

4. Physical environment

| (1) Interior design and decoration are visually appealing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (2) Layout and facilities are beautiful and interesting. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (3) Comfortable and clean tableware, tables, and chairs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (4) Convenient transportation and adequate parking | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (5) Lighting is appropriate and natural. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (6) Indoor temperature is comfortable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (7) Plenty space to taste and rest | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (8) Menu is attractive | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

5. Tourist satisfaction

| (1) I am satisfied with the overall food experience | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (2) Food is reasonably priced and valued for money | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (3) Tasting steamed pork is a unique and enjoyable experience | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (4) I felt that I had got what I wanted | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (5) This travel experience exceeded my expectations | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

6. Loyalty

| (1) I am willing to come here again to taste Jun’an steamed pork | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (2) I will praise Jun’an steamed pork | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (3) I would recommend others to taste Jun’an steamed pork | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

7. Basic information of tourists

(1) gender ① male ②female

(2) age: ① <21 ② 21–35 ③ 36–50 ④ 51–65 ⑤ >65

(3) education ① <junior high school ② high school ③ college ④ >master

(4) personal monthly income (CNY)

① <4000 ② 4000–8000 ③ 8000–12,000 ④ 12,000–16,000 ⑤ >16,000

References

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Okumus, F.; McKercher, B. Incorporating local and international cuisines in the marketing of tourism destinations: The cases of Hong Kong and Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.C.Y.; Kivela, J.; Mak, A.H.N. Attributes that influence the evaluation of travel dining experience: When East meets West. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Laguna, M.; Buhalis, D. Impacts of authenticity, degree of adaptation and cultural contrast on travellers’ memorable gastronomy experiences. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Avieli, N. Food in tourism: Attraction and Impediment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 755–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, G.E.D.; Heath, E.; Alberts, N. The Role of Local and Regional Food in Destination Marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2003, 14, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L. Chapter 1—The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In Food Tourism Around the World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bessière, J. ‘Heritagisation’, a challenge for tourism promotion and regional development: An example of food heritage. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, G. Feeding the Rural Tourism Strategy? Food and Notions of Place and Identity. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.C.Y.; Kivela, J.; Mak, A.H.N. Food preferences of Chinese tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 989–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimóthy, S.; Mykletun, R.J. Scary food: Commodifying culinary heritage as meal adventures in tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, E.; Lamb, D. Extraordinary or ordinary? Food tourism motivations of Japanese domestic noodle tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G. Entrepreneurial strategies in leveraging food as a tourist resource: A cross-regional analysis in Italy AU—Presenza, Angelo. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, A.H.N.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A. Globalisation and food consumption in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M.S. The effects of perceived authenticity, information search behaviour, motivation and destination imagery on cultural behavioural intentions of tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lego Muñoz, C.; Wood, N.T. A recipe for success: Understanding regional perceptions of authenticity in themed restaurants. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 3, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antun, J.M.; Frash, R.E., Jr.; Costen, W.; Runyan, R.C. Accurately Assessing Expectations Most Important to Restaurant Patrons: The Creation of the DinEX Scale. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2010, 13, 360–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Food and the tourism experience: Major findings and policy orientations. In Food and the Tourism Experience; Dodd, D., Ed.; OECD: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, J.; Jang, S. Effects of service quality and food quality: The moderating role of atmospherics in an ethnic restaurant segment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.A.; Berry, L.L. The Combined Effects of the Physical Environment and Employee Behavior on Customer Perception of Restaurant Service Quality. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2007, 48, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujisic, M.; Hutchinson, J.; Parsa, H.G. The effects of restaurant quality attributes on customer behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 1270–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Parsa, H.G.; Gregory, A. Restaurant QSC inspections and financial performance: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 23, 982–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K.; Parsa, H.G.; Parsa, R.A.; Bujisic, M. Change in Consumer Patronage and Willingness to Pay at Different Levels of Service Attributes in Restaurants: A Study in India. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 15, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njite, D.; Njoroge, J.; Parsa, H.; Parsa, R.; van der Rest, J.-P. Consumer patronage and willingness-to-pay at different levels of restaurant attributes: A study from Kenya. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugosi, P. Campus foodservice experiences and student wellbeing: An integrative review for design and service interventions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Seo, S.; Choi, J. Identifying restaurant satisfiers and dissatisfiers: Suggestions from online reviews. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 601–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longart, P.; Wickens, E.; Bakir, A. An Investigation into Restaurant Attributes: A Basis for a Typology. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018, 19, 95–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choe, J.Y.; Lee, S. How are food value video clips effective in promoting food tourism? Generation Y versus non-Generation, Y. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, S.; Fernandez, P.M. The Influence of Event Authenticity and Quality Attributes on Behavioral Intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 40, 685–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Shunde, Gastronomy. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/creative-cities/shunde (accessed on 4 April 2019).

- Krystallis, A. The Concept of Authenticity and its Relevance to Consumers: Country and Place Branding in the context of Food Authenticity. In Food Authentication: Management, Analysis and Regulation; Georgiou, C.A., Danezis, G.P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 27–84. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C.J.; Reisinger, Y. Understanding existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B.; Farrelly, F.J. The Quest for Authenticity in Consumption: Consumers’ Purposive Choice of Authentic Cues to Shape Experienced Outcomes. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Costello, C. Culinary tourism: Satisfaction with a culinary event utilizing importance-performance grid analysis. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.S.R.; Getz, D. Profiling potential food tourists: An Australian study. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.N.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A.; Chang, R.C.Y. The effects of food-related personality traits on tourist food consumption motivations. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Yuan, J.; Goh, B.K.; Antun, J.M. Web Marketing in Food Tourism: A Content Analysis of Web Sites in West Texas. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2009, 7, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, B.; Seyitoğlu, F. A conceptual study of gastronomical quests of tourists: Authenticity or safety and comfort? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Ron, A.S. Understanding heritage cuisines and tourism: Identity, image, authenticity, and change. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Response to Yeoman et al.: The fakery of ‘The authentic tourist’. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1139–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-T.; Lu, P.-H. Authentic dining experiences in ethnic theme restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondnejad, A. Tourist loyalty to a local cultural event: The case of Turkmen handicrafts festival. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, S.; King, B.E.M.; Morrison, A.; Nguyen, T.-H. Destination Encounters with Local Food: The Experience of International Visitors in Indonesia. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2017, 17, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klag, S.; Bowen, J.; Sparks, B. Restaurants and the tourist market. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2003, 15, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sage, C. Social embeddedness and relations of regard: Alternative ‘good food’ networks in south-west Ireland. International Perspectives on Alternative Agro-Food Networks: Quality, Embeddedness, Bio-Politics. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.M. Culinary Tourism; The University Press of Kentucky: Kentucky, KY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, V.; Ross, W.T.; Baldasare, P.M. The Asymmetric Impact of Negative and Positive Attribute-Level Performance on Overall Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Namkung, Y. Perceived quality, emotions, and behavioral intentions: Application of an extended Mehrabian–Russell model to restaurants. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Slevitch, L.; Tomas, S. The effects of restaurant attributes on satisfaction and return patronage intentions: Evidence from solo diners’ experiences in the United States. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, H.R.; Kim, W.G. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.S.; Luo, M.; Zhu, D.H. The Effect of Quality Attributes on Visiting Consumers’ Patronage Intentions of Green Restaurants. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.L.; Draper, J. Importance—Performance Analysis of the Attributes of a Cultural Festival. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2013, 14, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Atmospherics as a marketing tool. J. Retail. 1973, 49, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulek, J.M.; Hensley, R.L. The Relative Importance of Food, Atmosphere, and Fairness of Wait: The Case of a Full-service Restaurant. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2004, 45, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Moital, M.; da Costa, C.F.; Peres, R. The determinants of gastronomic tourists’ satisfaction: A second-order factor analysis. J. Foodserv. 2008, 19, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tse, E.C.-Y. Exploring factors on customers’ restaurant choice: An analysis of restaurant attributes. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2289–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Whaley, J.E. Determinants of dining satisfaction. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, M.; Malik, S.A.; Ahmad, M.; Shabbir, A. Perceptions of fine dining restaurants in Pakistan: What influences customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions? Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.; Feinstein, A.H.; Dalbor, M. Customer Satisfaction of Theme Restaurant Attributes and Their Influence on Return Intent. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2004, 7, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.Y.; Mattila, A.S. Restaurant Servicescape, Service Encounter, and Perceived Congruency on Customers’ Emotions and Satisfaction. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Measurement and evaluation of satisfaction processes in retail settings. Retailing 1981, 57, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C. A National Customer Satisfaction Barometer: The Swedish Experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, D.K.; Wilton, P.C. Models of Consumer Satisfaction Formation: An Extension. J. Res. 1988, 25, 204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam, A.; Neumann, Y.; Reichel, A. Dimentions of tourist satisfaction with a destination area. Ann. Tour. Res. 1978, 5, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Paggiaro, A. Investigating the role of festivalscape in culinary tourism: The case of food and wine events. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, V.G.; Chen, C.-F. Authenticity, experience, and loyalty in the festival context: Evidence from the San Fermin festival, Spain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Jung, S. Festival attributes and perceptions: A meta-analysis of relationships with satisfaction and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Tourism Destination Loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, S.J.; Crompton, J.L. The usefulness of selected variables for predicting activity loyalty. Leis. Sci. 1991, 13, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Kim, J.-H. Effects of ingredients, names and stories about food origins on perceived authenticity and purchase intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 6, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Inbakaran, R.; Reece, J. Consumer research in the restaurant environment, Part 1: A conceptual model of dining satisfaction and return patronage. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1999, 11, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Does Food Quality Really Matter in Restaurants? Its Impact on Customer Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2007, 31, 387–409. [Google Scholar]

- Karki, D.; Panthi, A. A Study on Nepalese Restaurants in Finland: How Food Quality, Price, Ambiance and Service Quality Effects Customer Satisfaction; Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences: Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Raajpoot, N.A. TANGSERV: A Multiple Item Scale for Measuring Tangible Quality in Foodservice Industry. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2002, 5, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jang, S. Perceptions of Chinese restaurants in the U.S.: What affects customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Crespi-Vallbona, M. Role of food neophilia in food market tourists’ motivational construct: The case of La Boqueria in Barcelona, Spain. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; James, H.G. The eight principles of strategic authenticity. Strategy Leadersh. 2008, 36, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Impact of hotel-restaurant image and quality of physical-environment, service, and food on satisfaction and intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.C.; Robinson, R.N.S.; Scott, N. Traditional food consumption behaviour: The case of Taiwan. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeset, M.G.; Elvekrok, I. Authentic concepts: Effects on tourist satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gálvez, J.C.; Granda, M.J.; López-Guzmán, T.; Coronel, J.R. Local gastronomy, culture and tourism sustainable cities: The behavior of the American tourist. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, K.W.; Mandabach, K.H.; McDowall, S.; VanLeeuwen, D.M. Perceptions of Quality, Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Approximate Spending at an American Wine Festival. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2012, 10, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Clifford, C. Authenticity and festival foodservice experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 571–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Baker, M.A. The Impacts of Service Provider Name, Ethnicity, and Menu Information on Perceived Authenticity and Behaviors. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gálvez, J.C.; Torres-Naranjo, M.; Lopez-Guzman, T.; Franco, M.C. Tourism demand of a WHS destination: An analysis from the viewpoint of gastronomy. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).