Abstract

This purpose of the study is to examine the relationships between food experiences, attitudes towards Sichuan cuisine, intention to revisit a restaurant, and intention to visit the city of origin (Chengdu). Results show that intellectual food experience and intention to revisit the restaurant have a significant effect on intention to visit the city of origin, whereas behavioural food experience and attitude towards food authenticity positively influenced intention to revisit the restaurant. Attitude towards food authenticity plays a vital role in the relationships between food experience, intention to revisit the restaurant, and intention to visit the city of origin.

Keywords:

food experience; attitude; Sichuan cuisine; city of origin; food authenticity; food novelty; China 1. Introduction

Food has traditionally been a highly significant component of tourist experience [1] as it provides a sensory experience to a tourist’s holiday [2]. Food expenses is considered a major part of the average tourist budget [3], and tourists eat local food not only to meet the need for sustenance, but also to understand the culture of a city, a region or a nation [4,5,6]. To date, culinary tourism or gastronomic tourism has mostly been considered to be a new way of approaching tourism or a certain type of tourism, for example, "gourmet tours" are recognized as being one of the fastest growing tourism trends [7]. According to the 2016 Food Travel Monitor, 81% of leisure travellers who responded like to learn about food and drink when they visit a destination [8]. In addition, World Travel Association records the food tourism industry to generate more than $150 billion every year [9]. China is a multi-ethnic country, and different people have unique delicacy and food cultures. According to a survey regarding food consumption and tourism catering from the China Customer Association in 2013, 92.31% of consumers look at the characteristic food of a region when choosing a tourism destination and to look for local delicacies is a great purpose and motivation for travel [10]. Sichuan cuisine originating from southwestern China is considered to be one the most popular Chinese cuisines. Chengdu, a rendezvous for Sichuan cuisine, is one of the four big cuisines of the Han nationality traditional Chinese and one of China’s eight regional cuisines. In addition, Sichuan cuisine is celebrated as one of the most popular out-of-home dining foods and has drawn tourists from far and wide to enjoy the cuisine in Chengdu, Sichuan province. Chengdu is famed for its diverse and spicy foods and was also awarded the “City of Gastronomy” by UNESCO in 2011 [11]. In the recent years of economic development, Chengdu has become the chosen venue for expos and fairs on food and beverage. In the comprehensive analysis of the country’s 80 million hits, searches, reviews and other information users discovered that after the first half of 2015, the fastest growing domestic tourism destination is Chengdu [12].

Unlike other forms of tourist activities, food in tourism can be considered to be an art form that can gratify human senses such as vision, tactile, auditory, taste and olfaction [5]. In addition, food can provide cultural insights into a destination and society, as a result it can create substantial appeal as a tourist destination [1,5,6]. It was stated by Gajic that gastronomic tourism is a growth are in the tourism industry [13]. Furthermore, the understanding of cuisine as part of a food brand and experience requires further attention [14,15], as there are only a handful of studies to date that address food as a brand that create experiences and impacts on consumer behaviour in a tourism context [15,16]. In addition, limited attention and studies have focused on the factors that affect a food tourist’s psychological and behavioural state in a food tourism context [14]. Based on extant literature reviews, the majority of the research on food tourism is predominantly focused on Western tourists, therefore studies of non-Western and Asian tourists are scarce [16]. In addition, studies have often focused on Chinese tourists as an outbound tourist to international destinations [6,13] as opposed to domestic travellers. Furthermore, domestic tourism in China is a major contribution to tourist arrivals, revenues and traffic than the international market [17,18], presenting the domestic traveller as a valuable consumer. Based on the literature, there is a present gap in better understanding Chinese domestic tourist behaviour [18,19], especially in the context of food tourism [16].

Therefore, the focus of the study is to explore the impact of Sichuan food experience on attitudes towards Sichuan cuisine, and consumer’s revisit intention to the restaurant, and intention to visit the city of origin. Testing tourists’ food experiences and examining their effect on the attitude of Sichuan cuisine, intention to visit the city of origin contributes to the further development of food tourism in China and other destinations.

2. Relevant Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Gastronomic Tourism

Gastronomy as a subject has advanced significantly since the early 1990s, with theory in the spheres of culinary arts, culinary science, and technology developing pace [20]. Gastronomic tourism, also called culinary tourism or food tourism, considers gastronomy within the tourism perspective [21]. Gastronomic tourism refers to trips made to destinations where the local food and beverages are the primary motivating factors for travel. Gastro-tourism activities include a broad spectrum of food and culinary activities, general created to enhance visitors’ experiences while at a destination [22]. Meanwhile, gastronomy as a unique attraction become a main aspect of destination branding or place branding [23,24,25]. The difference between local and international foods (local vs regional food) in destination marketing plays a distinctive role in attracting tourists by socio-cultural characteristics of food [26,27].

Local food plays an important role in different destinations in the food tourism industry, such as Hot pot in Chongqing of China [16] and local cuisines in four Caribbean islands [28]. According to Nummedal and Hall, local food is defined as the food and drink that are locally produced and grown within the local area or region, or local specialty food that has a local identity [29]. These types of foods are distinctively different to non-local products by characteristics, social features and ecological features [30]. In addition, cultural influence plays a role in the preference for local cuisines, in particular the sensory properties of local foods. Specifically, these culturally specific cooking techniques and “flavour principles” (the distinctive seasoning combinations) characterizes different cuisines [31]. Boyne, Hall and Williams argued the importance of food-related tourism by policy, support and promotion [32]. Gordin et al. displayed the significance of hotel restaurants in gastronomic place branding [25]. Moreover, Liu discussed about the relationship among brand equity, culinary attraction and tourism satisfaction [33]. Prat Forga and Valiente discussed the importance of satisfaction for improving culinary tourism development [34]. Min and Lee explored Australian residents’ satisfaction with the experience of Korean cuisine and intention to visit Korea [35]. Hence, gastronomic tourism not only provides economic benefits to a city or a place, but also spreads local food culture to tourism managers. In addition, food offers tourists novelty and enjoyment which they can consume as part of the local culture [27,36]. While it is popular belief that food in tourism is considered to be an attraction, there have also been studies to state that local cuisine can be seen as a risk factor if foods are perceived as “strange” and “unfamiliar” [6,37].

2.2. Brand Experience

Experience is a feeling and an internal reflection of consumer to certain stimuli from a product or a service [38,39]. There are different forms of experiences identified within marketing literature, including consumer experience, product experience, shopping experience, and service experience [40]. The 21st century is the era of an experience economy, whereby experiences are the core of service economy and marketing [41]. As a result, marketing researchers and practitioners have come to realize that understanding how customers’ brand experience is vital to improving marketing strategies for a product or a service. Brakus, Schmitt and Zarantonello conceptualized brand experience as “internal consumer responses like behavioural responses, such as sensory, feeling, cultural and cognitions evoked by related brand stimuli that are part of a brand’s design and identity, packaging, communication, and environments”, and distinguished the related concepts, such as brand attitudes, brand personality, and brand attachment [42]. Schmitt defined that brand experience has five factors including thinking, feeling, and action [38].

Meanwhile, brand experience measures as developed by Brakus et al. [42] and Zarantonello, Schmitt and Brakus [43] included four dimensions such as sensory, affective, intellectual, and behavioural brand experience. Sensory brand experience refers to bodily experiences based on visual, olfactory, or tactile experiences, e.g., the colour of the food, the smell of the food, the taste of the food. Affective brand experience refers to feelings, sentiments and emotions, e.g., feeling the memories of the food. Intellectual brand experience refers to thought, stimulation of curiosity and problem-solving, e.g., thinking the culture of the food and comprehending the related culture. Finally, behavioural brand experience refers to physical actions and behaviours, e.g., searching related information and repurchasing related products and services. While other researchers in the tourism and marketing field have used constructs that may be construed as sensory, affective, intellectual, or behavioural, Beckman, Kumar and Kim identified brand experience impact on place dependence and future behaviour such as word-of-mouth and revisit intention, using the data both tourists and locals [44].

Barnes et al. examined the relationship in destination brand experience, satisfaction, intention to revisit and intention to recommend, and pointed out that destination brand experience plays a positive role in determining revisit intentions and word-of-mouth recommendation in the tourism context [45]. Morgan-Thomas and Veloutsou designed an integrative model of online brand experience combining marketing and information systems, present that trust and perceived usefulness have strong positive effect on brand experience in an internet environment [46]. Hamzah, Alwi, and Othman analysed the elements of corporate brand experience in an online banking setting, and found out five main factors including visual, functionality, emotional, lifestyle and self-identity [47]. Meanwhile, some research indicated that brand experience significantly influenced both brand trust and brand satisfaction [48,49,50]. Moreover, brand experience will impact on brand loyalty [51,52]. Therefore, brand experience not only provides a happiness experience to visitors, but also brings some operational strategies to marketing managers. In addition, Beckman et al. stressed the importance of sensory brand experiences for tourists to encourage revisit intention [44].

2.3. Food Experience as a Part of Destination Brand Experience

It has been reiterated in previous research that food is a touristic experience [16,53,54]. As previous researchers have suggested, brand experience and brand attitude are two related different concepts. Brand experience typically is seen as brand-related stimuli [42]. In addition, brand attitude is evaluative based on consumers’ post-use. In the field of marketing, brand experience should be input to brand attitude and has a critical effect on the attitude of a product or a service [55,56,57]. For a travel experience, it can serve to cement and reinforce the emotional connection between the traveller and the destination [58,59]. There is evidence from global tourism boards to integrate food as part of the tourist destination experience as food is directly or indirectly connected to a place, which also encourages tourists to experience a region’s taste through its cuisine [7].

According to Kim, Eves and Scarles, smell, taste, and visual images of food can enhance the sensory appeal and experience of local food [13]. Several studies have highlighted the importance of flavour and taste of local food for tourist satisfaction and experience (e.g., Boniface, 2001 [60]; Dann and Jacobsen [61]). As a result, the taste of food in the tourism setting is pivotal in attracting tourists to a destination and is a valuable aspect of tourism consumption [62]. Björk et al. also found a direct link between food experience and attitude towards food within the tourism field [23]. Based on the above discussion, the following is hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Food experience (a) sensory, (b) affective, (c) behavioural and (d) intellectual has a positive influence on attitude towards food authenticity.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Food experience (a) sensory, (b) affective, (c) behavioural and (d) intellectual has a positive influence on attitude towards food novelty.

Previous studies in the field of food tourism have often addressed the effect of intention to revisit or repurchase products or services (e.g., Barsky and Labagh [63]; Yoon and Uysal [64]). Evidence suggests that brand experience plays a key role in revisit intention. For example, Beckman et al. (2013) identified brand experience influence on place dependence and positive outcomes such as word-of-mouth and revisit intention [44]. Branes et al. (2014) found that sensory and affective destination brand experience are positively related to revisit intention [65]. Based on the above discussion, the following is hypothesized:

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Food experience (a) sensory, (b) affective, (c) behavioural and (d) intellectual has a positive influence on intention to revisit Sichuan restaurant.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Food experience (a) sensory, (b) affective, (c) behavioural and (d) intellectual has a positive influence on intention to visit the city of origin for Sichuan cuisine.

2.4. Attitude towards Sichuan Cuisine

Concerning the attitudes towards a cuisine, a person may hold different attitudes towards the same food. The relationship between consumer attitude and behavioural intention has been examined in the theory of planned behaviour, and theory of reasoned action as well as its applications in various fields [14,66]. Attitude has found to play an important and major role in tourist consumption behaviour and in social sciences [14]. In particular, Kim, Eves and Scarles found that local food and beverage form a part of authentic travel experiences, which are unique and original to the destination [13]. The study also found that these local food experiences are not replicable at home. Even if it could be attainable back home, it would taste different. The blend of ingredients, cooking skills, and the preservation of food and differences between countries forms the authentic and traditional culture behind local food [67], thus solidifying the value of eating food at its original place of origin. Similarly, in Ryu and Han’s study, attitudes towards the local cuisine has a significant impact on affecting behavioural intentions and outcomes [68]. It was also found that local cuisines can strengthen or attract tourists to a destination, as it can affect the way tourists experience a destination. Hence, the importance of culinary experiences in marketing a tourist destination. It was found in the study by Chang, Kivela and Mak [6] that the reason to consume local cuisine is to experience “authenticity” in the travel experience. With cuisines, it can add greater value to cultural and intellectual experience than physical pleasure. As a result, tourists seek unique and original culinary experiences while travelling. Therefore, a tourist’s need for authenticity is considered to be an important motivator in tourism experiences [69,70].

Along a similar vein, Guan and Jones found that attitudes and perceptions towards local cuisine will impact on the attractiveness of the destination, thereby providing motivation to visit the city of origin of the cuisine [71]. In another study, Jung, Kim and Kim conducted an empirical study to illustrate the relationships between attitudes towards online brand community and revisit intention [72]. They found that the moderating effect of the type of online community was significant in predicting the relationship between attitude and brand trust but not between attitude and revisit intention; however, attitude affects the revisit intention. Meanwhile, revisit intention will impact visit the city of origin for consumer. Based on the above discussion, the following is hypothesized:

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Attitude towards (a) food authenticity and (b) food novelty of Sichuan cuisine has a positive relationship on the intention to revisit a Sichuan restaurant.

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

Attitude (a) food authenticity and (b) food novelty of Sichuan cuisine has a positive relationship on the intention to visit the city of origin for Sichuan cuisine.

Hypothesis 7 (H7):

Intention to revisit a Sichuan restaurant has a significant relationship on intention to visit the city of origin of Sichuan cuisine.

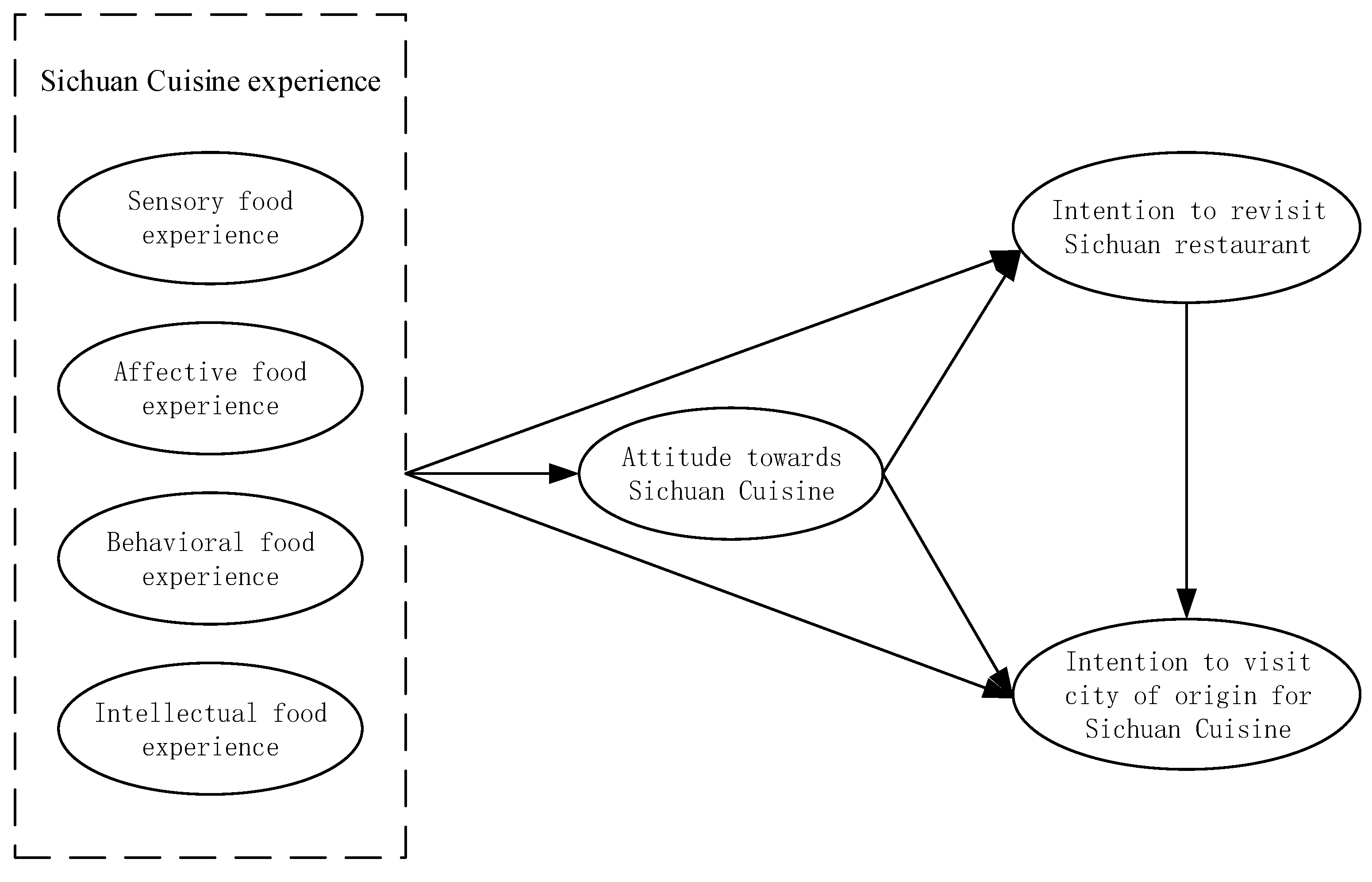

Taken together, the research model is as follows (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research Model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

The study focuses on the consumer who has tasted Sichuan cuisine in China and explores the relationship among food experience, intention to revisit the restaurant and visit the city of origin. Thus, since the survey method is best way to meet this aim, a web-based questionnaire was used to collect the data. Specifically, a self-administered online survey was used for data collection through a professional internet research website that randomly selected participants from its online panel. Respondents were instructed to complete the questionnaire only if they had prior tasting Sichuan cuisine. The respondents are restricted to mainland Chinese travellers. The survey was translated into Chinese by a native Chinese speaker, and was back-translated into English to ensure consistency.

3.2. Measurement

The questionnaire includes multiple items to measure sensory food experience, affective food experience, behavioural food experience, intellectual food experience, attitude towards Sichuan cuisine, intention to revisit Sichuan restaurant and intention to visit the city of origin of Sichuan cuisine. Most of the construction items adapted from the excellent literature, as using the developed scales by researcher can ensure the reliability and validity of questionnaire [73]. Because there were no existing items for attitude towards Sichuan cuisine, we developed new items for this construct. First, we searched the related literature on the attitude of Sichuan food [74] and gathered the initial items. Second, we asked ten Sichuan cuisine experts and ten consumers to review these items. In evaluation of respondent’s comments, the items are revised to better relate to the context of food tourism. Third, an initial exploratory factor analysis using VARIMAX rotation with SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was undertaken to examine the 11 scale items that represented attitude towards Sichuan cuisine (food authenticity and food novelty). The final two-factor solution identified seven items that explained 63.703% of the variance with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.893 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity of 2059.808 (p = 0.000). So we gain two factors, food authenticity factor and food novelty factor, and also tested the reliability.

Section A of the survey instrument comprised the attitude towards Sichuan cuisine measurements. There are four items of attitude towards Sichuan cuisine (food appearance), which consists of items such as “I find Sichuan cuisine appetising”. There are three items that measure attitudes towards Sichuan cuisine (novelty), examples are “I find Sichuan cuisine creative”. This is followed by a three-item scale measuring sensory food experience developed by Brakus et al. [42] and a three-item scale measuring affective food experience developed by Barnes, Mattsson and Sørensen [45]. Section B included a three-item scale measuring behavioural food experience developed by Beckman et al. [44]. This is followed by a four-item scale measuring intellectual food experience improved by Brakus et al. [42]; a three-item scale measuring intention to revisit Sichuan restaurant developed by Qu, Kim and Im [75]; and a four-item scale measuring intention to visit the city of origin towards Sichuan cuisine developed by Chung, Han and Joun [76]. Lastly, Section C of the survey instrument comprised of questions that captures the demographic information of the respondents. The final items and sources are listed in Appendix A. Each of the items were measured on a sevenpoint Likert scale with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 7 “strongly agree”. A total of 321 usable questionnaires were obtained, which is deemed an appropriate sample size for running structural equation models using Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) estimation [77].

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The survey resulted in a collection of 321 valid responses, where 145 from males (45.2%) and 176 from females (54.8%). The majority age category of respondents was 19-29 years of age (76.6%), followed by 30–39 years of age (18.4%), 40–49 years of age (4.4%) and under 18 years of age (0.6%), reflecting that more mature customers patronize the Sichuan restaurant. The sample was comprised of single (61.7%), married (25.2%), cohabit (10.0%) and others (3.1%). Many of respondents held postgraduate degree (55.1%), followed by getting a university degree (23.1%), college or university student (20.9%), and secondary school (0.9%). Most of respondents are student (57.6%) with below 20,000 annual income (52.6%). The frequency analysis of the sample is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of respondents.

4.2. Reliability Analysis and Validity Analysis

To ensure the validity of the survey data, a measurement model was constructed to test the reliability and validity of the instrument. Firstly, Cronbach’s α and construct reliability (CR) were used to assess the reliability of multi-item scales for each construct. Cronbach’s α of all key variables were computed: sensory food experience (0.823), affective food experience (0.903), behavioural food experience (0.910), intellectual food experience (0.898), attitude towards Sichuan cuisine (food appearance) (0.888), attitude towards Sichuan cuisine (novelty) (0.812), intention to revisit Sichuan restaurant (0.938) and intention to visit the city of origin for Sichuan cuisine (0.925). Table 2 showed that all the alpha coefficients were greater than the cut-off point of 0.7 [78], suggesting a high level of internal consistency for each construct. In addition, all construct reliabilities exceeded the recommended threshold values [78] of 0.7. These showed good reliability.

Table 2.

Items, Reliability, Coefficient, and AVE of variables.

Secondly, convergent validity and discriminant validity were available to measure the validity. Table 2 listed that the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct. Also, convergent validity was supported by the fact that all AVEs exceed 0.5 [79]. In addition, as shown in Table 3, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results lent further support for the convergent and discriminant validity among all constructs. The discriminant validity of the eight proposed constructs was tested by contrasting the eight-factor model against alternative models. Considering all antecedent variables are equally associated with food brand experience, we constructed competing models such as the 8-, 7-, 5-and 1-factor models. The 8-factor model is a complete model, the 7-factor model is a combination of attitudes towards Sichuan cuisine (food authenticity and food novelty) or intention to revisit restaurant and intention to visit the city of origin, and the 5-factor model is a combination of sensory, affective, behaviour, and intellectual food experience. The model comparison results in Table 3 show that the eight-factor model fit the data considerably better than any of the alternative models. The proposed model fits the data well (; P < 0.001; = 2.551; GFI = 0.850; AGFI = 0.808; CFI = 0.937; IFI = 0.938; TLI = 0.925; RMSEA = 0.070). Thus, the distinctiveness of the eight constructs in this study was required to be supported. Given these consequences, all eight constructs were applied in subsequent analyses.

Table 3.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis for the measures of the variables studied.

4.3. Descriptive Analysis

Table 4 displays the correlations, means and standard deviations of all latent variables. As indicated in the table, the correlations of the key variables are in the expected direction. Food brand experience, including sensory, affective, behavioural, and intellectual, has been found to be positively correlated with attitudes towards food authenticity, attitudes towards food novelty, intention to revisit the restaurant and intention to visit the city of origin. Meanwhile, attitude towards food authenticity was found to be positively correlated with intention to revisit the restaurant and intention to visit the city of origin (r =0.638, p < 0.01; r = 0.535, p < 0.01). Attitude towards food novelty was found to be positively correlated with intention to revisit the restaurant and intention to visit the city of origin (r = 0.419, p < 0.01; r = 0.456, p < 0.01). Moreover, intention to revisit the restaurant was found to be positively correlated with intention to visit the city of origin (r = 0.671, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations.

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

To test the hypotheses, the research model proposed causal relationship between the factors and path analysis was undertaken using AMOS 22.0. As can be shown in Table 5, the goodness-of-fit indices were acceptable: = 2.551 < 3; goodness-of-fit-index (GFI) = 0.850 > 0.8 [80]; AGFI=0.808 > 0.8 [81] (MacCallum and Hong, 1997); comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.937; incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.938; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.925; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.070 < 0.08. Most of goodness-of-fit indices were above the critical level [78] and the model was acceptable.

Table 5.

Results for Path Analysis.

The results of hypotheses testing showed some significant conclusions. Sensory and intellectual food experience produced positive and significant effects on attitude towards food authenticity, supported H1a and H1d. Intellectual food experience had a strong positive influence on attitudes towards food novelty towards Sichuan cuisine, supported H2d. Positive and significant effects were found in behavioural food experience and intention to revisit the restaurant, supported H3c. Intellectual food experience produced positive and significant effects on intention to visit the city of origin, supported H4d. As expected, a particularly strong positive and significant effect was observed between attitudes towards Sichuan cuisine (authenticity), attitudes towards Sichuan cuisine (novelty), and intention to revisit the restaurant, strongly supported H8 and H5a. Meanwhile, intention to revisit the restaurant also produced positive and significant effects on intention to visit the city of origin, supported H7. However, there were differences in fifteen of the hypothesized results. For example, food experience (sensory, affective and behavioural) were found to have no significant effects on attitude towards Sichuan cuisine (novelty). A summary of results from hypothesis testing is shown in Table 5.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study concentrated on investigating the relationship among food experience, attitudes towards Sichuan cuisine, intention of revisiting the restaurant and visiting the city of origin. First, food experience (sensory, intellectual) was found to be positively related to attitude (authenticity) on Sichuan cuisine. Second, attitude (authenticity) was found to be positively related to intention for revisiting restaurant. Third, intention to revisit restaurant was found to be positively related to intention for visiting city of origin.

This study contributes to the growing literature on food experience and food tourism. First, we developed a model to explain food experience in relation to tourists’ attitudes towards food tourism. The model predicts that food experience affects intention to visit city of origin. It not only extends Barnes’ et al. research about destination brand experience [45], but also extends some research towards culinary destination marketing [2] and destination identify [7]. Meanwhile, we found that intellectual food experience has a significant positive relationship towards consumers’ intention to visit city of origin of the cuisine. In particular, this reinforces some of the previous studies on the fact that food and destination go hand in hand. It is worth noting that little attention has been committed to addressing the effect of food culture, especially in the gastronomic tourism field. This is supported by Chang, Kivela and Mak [6], where local culture is one of the key motivators for engaging in a novel or local cuisine. Second, we developed a scale for Sichuan cuisine, and examined the relationship between food experience and intention to visit the city of origin. We found that intellectual food experience has a significant positive relationship food attitude (authentic), and attitude (authentic) has a significant positive relationship intention to revisit restaurant. Similar to previous studies, consumption of food is not entirely for utilitarian reasons such as to satisfy hunger or thirst, but an avenue to gain in depth knowledge into a regional cuisine [5]. Meanwhile, authentic experiences shape the attractiveness of the origin of the cuisine [71,82,83] elucidated and validated the influence of tourist experience on food, demonstrating the importance of food experience in tourism. Finally, this study is the first to consider customer revisit intention and visit the city of origin based on food experience perspective in a tourism setting. Previous studies mainly used food brand experience includes many different experiences, such as sensory, affective, behavioural and intellectual, and few researchers pay attention to its effects between food experience and intention to visit the city of origin. This study adds to the literature on gastronomic tourism behaviour and food experience by elucidating attitude.

This study also provides some important implications for destination and tourism managers. Firstly, by investigating the influence of food experience, it is found that sensory and intellectual food experiences are important to a food tourist and will impact on their attitude towards Sichuan cuisine. This also provides important implications to destination managers and branding managers to enhance the sensory experiences through visuals, olfactory, tactile and other stimulations to create a memorable experience for tourists [84]. Meanwhile, going beyond only the sensory experiences, tourists are also interested in an understanding of the local culture, origins and history of the food. Secondly, from this study, it was found that behavioural food experience such as trying and seeking out new experiences have a significant relationship towards revisiting a restaurant. This provides important insights to local restaurants to create items that can provide enticement and excitement for tourists to revisit. In particular, menu changes and specials will be able to provide new experiences even though it still caters to one particular cuisine. Thirdly, the results of this study show that attitude plays a vital role in the relationship between food experience and revisit intention. In particular, attitudes towards food authenticity of Sichuan cuisine is important in shaping behaviour. Therefore, in ensuring that the foods that tourists experience lives to provide an authentic experience is important in shaping their intentions to visit the city of origin. Fourthly, the present study suggests that consumer food experience can be cultivated by improving the likelihood of the gastronomic tourism, which is an extremely gratifying experience. This study may encourage restaurant managers to design programs that can help their customers experience food culture and cultivate customer attitude towards Sichuan cuisine. For example, there are restaurants that pair the food with local cultural art to enhance the consumption experience of the food with a snippet of the culture. This can help shape a holistic experience by enhancing intellectual and sensory food experiences. Namely the significance of cuisine serves as the window into the destination and culture. It is a strong branding and communication message for tourism boards to understand and communicate the origins and history of the foods to tourists as a result [9,71]. In addition, this will help to brand the identity of the city of origin – Sichuan in this case. Finally, this study helps managers to more thoroughly understand flow experience in daily catering services, especially intellectual food experience. City marketing managers may need to allocate more resources to create customer intellectual food experience by designing activities and marketing programmes that provides “food stories”.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are several limitations of this research that also offer some possibilities for further research. One of the limitations of study is the fact that it is not concerned with eating habits and knowledge level of cuisine. For future studies, focusing on eating habit or knowledge level of food is recommended, since tourists may have different demands and visiting motivations for different habits or knowledge levels [71]. For example, a tourist who visits the city of origin (i.e., tasting authentic local food, understanding local food culture, studying the way of cooking) might have different demands from gastronomic tourism than those who eat some food or cuisine at a non-local restaurant. In addition, food consumption at a tourist destination can also be an emotional experience. Therefore, future studies can examine the influence of emotions during the consumption process of local cuisine and how it affects behavioural outcomes [85]. This research suggests that future studies use more diverse aspects of research perspective, such as city marketing, city or place branding, food and drink culture, and that these focus on their possible influence on food tourism. In addition, since gastronomic tourism is a new kind of tourism and it might be varied depending on the country, for example Singapore, Australia, and America. Furthermore, this study considers only the food experience and attitude elements of consumers’ own dimensions. Thus, in future studies, additional tourist characteristics should be considered such as local tourist, non-local tourist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P. and I.P.; Formal analysis, B.P. and I.P.; Investigation, B.P., M.T., and I.P.; Writing—original draft preparation, B.P.; Writing—review and editing, B.P., M.T. and I.P.; Supervision, M.T. and I.P.; Funding acquisition, B.P.

Funding

This research was funded by funding from the Research Subject of Development and Research Center of Sichuan Cuisine (No: CC17G04), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 71804119) and the China Scholarship Council (CSC) (No. 201507000007).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Scales and items.

Table A1.

Scales and items.

| Construct | Scale Reference | Adapted Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Sensory food experience | Brakus et al. (2009) [42] | 1. Sichuan food makes a strong visual impression on me. |

| 2. Sichuan food makes a strong impression on my sense of taste. | ||

| 3. Sichuan food makes a strong impression on my sense of smell. | ||

| Affective food experience | Barnes et al. (2014) [65] | 1. Sichuan food induces my personal feelings and sentiments. |

| 2. I have strong emotions for Sichuan food. | ||

| 3. Sichuan food is an emotional experience. | ||

| Behavioural food experience | Beckman at al. (2013) [44] | 1. I physically engage in looking out for new Sichuan restaurants. |

| 2. I seek to experience new Sichuan dishes I have not tried before. | ||

| 3. I seek to experience Sichuan disahes in different restaurants. | ||

| Intellectual food experience | Brakus et al. (2009) [42] | 1. Sichuan food makes me think more about food culture. |

| 2. Sichuan food makes me think more about food origins. | ||

| 3. Sichuan food makes me curious about sensory food experiences. | ||

| 4. Sichuan food makes me understand the lifestyle of its people. | ||

| Attitude towards Sichuan Cuisine (authenticity) | Adapted from McKercher et al. (2008) [54] | 1. I think Sichuan food is appetising |

| 2. I think Sichuan food is aromatic | ||

| 3. I think Sichuan food is authentic | ||

| 4. I think Sichuan food is colourful | ||

| Attitude towards Sichuan Cuisine (novelty) | Adapted from McKercher et al. (2008) [54] | 1. I think Sichuan food is creative |

| 2. I think Sichuan food is different | ||

| 3. I think Sichuan food is innovative | ||

| Intention to revisit restaurant | Qu et al. (2011) [75] | 1. I look forward to eat Sichuan food at a Sichuan restaurant. |

| 2. I desire to eat Sichuan food at a Sichuan restaurant. | ||

| 3. I will eat Sichuan food at a Sichuan restaurant. | ||

| Intention to visit city of origin | Chung et al. (2015) [76] | 1. I intend to visit Chengdu, the city of origin of Sichuan food to try authentic Sichuan food. |

| 2. I plan to visit Chengdu, the city of origin of Sichuan food to try authentic Sichuan food. | ||

| 3. I will recommend others to visit Chengdu, the city of origin of Sichuan food to try authentic Sichuan food. | ||

| 4. If I get the chance to travel, I want to visit Chengdu, the city of origin of Sichuan food to try authentic Sichuan food. |

References

- Okumus, B.; Xiang, Y.; Hutchinson, J. Local cuisines and destination marketing: Cases of three cities in Shandong, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Cetin, G. Marketing Istanbul as a culinary destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J.; Wall, G. Strengthening Backward Economic Linkages: Local Food Purchasing by Three Indonesian Hotels. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Mossberg, L. Travel for the sake of food. Scandinavian. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Crotts, J.C. Tourism and Gastronomy: Gastronomy’s Influence on How Tourists Experience a Destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.C.Y.; Kivela, J.; Mak, A.H.N. Food preferences of Chinese tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 989–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Pearson, T.E.; Cai, L.A. Food as a form of Destination Identity: A Tourism Destination Brand Perspective. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.J.; Migacz, S. The 2016 Food Travel Monitor; World Food Travel Association: Portland, OR, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, S. Food and Drink Tourism: Principles and Practice; SAGE: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Food Consumption and Tourism Catering of China in 2013. Available online: http://www.chinanews.com/sh/2013/11-27/5551015.shtml (accessed on 17 March 2019).

- For Hot and Spicy, Sichuan Cuisine Leads the Pack. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/regional/2018-11/08/content_37225655.htm (accessed on 17 March 2019).

- 2015 Tourist Destination Report. Available online: http://www.chinanews.com/life/2015/06-10/7335003.shtml (accessed on 17 March 2019).

- Gajic, M. Gastronomic tourism-a way of tourism in growth. Quaestus 2015, 6, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, M.; Goh, B.K. An examination of food tourist’s behavior: Using the modified theory of reasoned action. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.S.; Liu, C.H.; Chou, H.Y.; Tsai, C.Y. Understanding the impact of culinary brand equity and destination familiarity on travel intentions. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, R. Understanding the importance of food tourism to Chongqing, China. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.P.; Liu, X.Y. A study on the changing trends of domestic tourism consumption composition of urban residents grouped by travel purpose in China. In Advances in Intelligent Systems Research, Proceedings of the International Conference on Economic Management and Trade Cooperation (EMTC), Xi’an, China, 12–13 April 2014; Wang, M., Ed.; Atlantic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Meng, F.; Zhang, Z. Non-participation of domestic tourism: Analyzing the influence of discouraging factors. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pearce, P. Tourist scams in the city: Challenges for domestic travellers in urban China. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povey, G. Gastronomy and tourism. In Research Themes for Tourism, 1st ed.; Robinson, P., Heitmann, S., Dieke, P., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2011; pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Silkes, C.A.; Cai, L.A.; Lehto, X.Y. Marketing to the culinary tourist. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Costello, C. Culinary tourism: Satisfaction with a culinary event using importance-performance grid analysis. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H.; Okumus, F.; Okumus, F. Local food: A source for destination attraction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rand, G.; Heath, E. Towards a framework for food tourism as an element of destination marketing. Curr. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 206–234. [Google Scholar]

- Gordin, V.; Trabskaya, J.; Zelenskaya, E.; Zins, A.; Dioko, L.A. The role of hotel restaurants in gastronomic place branding. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Okumus, F.; McKercher, B. Incorporating local and international cuisines in the marketing of tourism destinations: The cases of Hong Kong and Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, G.E.D.; Heath, E.; Alberts, N. The role of local and regional food in destination marketing: A South African situation analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2003, 14, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, F.; Kock, G.; Scantlebury, M.M.; Okumus, B. Using local cuisines when promoting small Caribbean island destinations. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummedal, M.; Hall, C.M. Local food in tourism: An investigation of the new zealand south island’s bed and breakfast sector’s use and perception of local food. Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 9, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, C. Social embeddedness and relations of regard: Alternative ‘good food’ networks in south-west ireland. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, E.; Rozin, P. Culinary themes and variations. Nat. Hist. 1981, 90, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Boyne, S.; Hall, D.; Williams, F. Policy, support and promotion for food-related tourism initiatives. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2003, 14, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.S. The Relationships among Brand Equity, Culinary Attraction, and Foreign Tourist Satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1143–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat Forga, J.M.; Valiente, G.C. The importance of satisfaction in relation to gastronomic tourism development. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-H.; Lee, T.J. Customer satisfaction with Korean restaurants in Australia and their role as ambassadors for tourism marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, I. Maslow’s hierarchy and food tourism in Finland: Five cases. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B.H. Experiential Marketing: How to Get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, Act, Relate to Your Company and Brands, 1st ed.; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, B.H.; Brakus, J.; Zarantonello, L. The current state and future of brand experience. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H.; Brakus, J.J. Development of the brand experience scale. Adv. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 580–582. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, E.; Kumar, A.; Kim, Y.-K. The impact of brand experience on downtown success. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J.; Sørensen, F. Destination brand experience and visitor behavior: Testing a scale in the tourism context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Thomas, A.; Veloutsou, C. Beyond technology acceptance: Brand relationships and online brand experience. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, Z.L.; Alwi, S.F.S.; Othman, M.N. Designing corporate brand experience in an online context: A qualitative insight. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, L.H.; Soo, K.M. The effect of brand experience on brand relationship quality. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2012, 16, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.A.; Jeong, M. Enhancing online brand experiences: An application of congruity theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Zehir, C.; Kitapçı, H. The effects of brand experiences, trust and satisfaction on building brand loyalty: An empirical research on global brands. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Singh, J.J.; Batista-Foguet, J.M. The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.; Cleff, T.; Chu, G. Brand experience’s influence on customer satisfaction and loyalty: A mirage in marketing research. Int. J. Manag. Res. Bus. Strategy 2013, 2, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L. The consumption of experience or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In Food Tourism around the World: Development, Management and Markets, 1st ed.; Mitchel Hall, C., Sharples, L., Mitchel, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Okumus, F.; Okumus, B. Food tourism as viable market segment: It is all how you cook the numbers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, K.-S.; Cyril de Run, E.; Shukla, P.; Shamim, A.; Mohsin Butt, M. A critical model of brand experience consequences. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2013, 25, 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. Using the brand experience scale to profile consumers and predict consumer behaviour. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. The impact of event marketing on brand equity: The mediating roles of brand experience and brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2013, 32, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, C.; Levy, S.E.; Ritchie, B. Destination branding: Insights and practices from destination management organizations. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Ritchie, B.J.R. Branding a memorable destination experience. The case of ‘Brand Canada’. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, P. Dynamic Tourism: Journeying with Change, 1st ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G.M.S.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Leading the Tourist by the Nose. In The Tourist as a Metaphor of the Social World, 1st ed.; Dann, G.M.S., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, K. Demand for the gastronomy tourism product: Motivational factors. In Tourism Gastronomy, 1st ed.; Hjalager, A.M., Richards, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barsky, J.D.; Labagh, R. A Strategy for Customer Satisfaction. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1992, 33, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, N. Social Commerce Emerges as Big Brands Position Themselves to Turn ‘Follows’ ‘Likes’ and ‘Pins’ into Sales. In Proceedings of the Marketing Management Association Annual Spring Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–28 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.S.; Hsu, C.H. Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G.; Liska, A. ‘McDisneyzation’ and ‘post-tourism’: Complementary perspectives on contemporary tourism. In Touring Cultures. Transformations of Travel and Theory; Rojek, C., Urry, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H. Predicting tourists’ intention to try local cuisine using a modified theory of reasoned action: The case of New Orleans. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Beyond authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Jones, D.L. The contribution of local cuisine to destination attractiveness: An analysis involving Chinese tourists’ heterogeneous preferences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Influence of consumer attitude toward online brand community on revisit intention and brand trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.C.; Gefen, D. Validation guidelines for IS positivist research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R. Introduction to Chinese Food Culture, 1st ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Han, H.; Joun, Y. Tourists’ intention to visit a destination: The role of augmented reality (AR) application for a heritage site. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. Stat. Strateg. Small Sample Res. 1999, 2, 307–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, W.J.; Xia, W.; Torkzadeh, G. A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. Mis Q. 1994, 18, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Hong, S. Power analysis in covariance structure modeling using GFI and AGFI. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1997, 32, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A. Globalisation and food consumption in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S. Beyond the visual gaze? The pursuit of an embodied experience through food tourism. Tour. Stud. 2008, 8, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, H. Vernacular health moralities and culinary tourism in Newfoundland and Labrador. J. Am. Folk. 2009, 122, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).