2. Background Literature

The field of corporate sustainability is highly complex and still comprises some unknown areas. Even its definition is still debatable with several ideas, concepts and approaches introduced as a way to achieve it. By nature, corporate sustainability is a multidisciplinary field. With that in mind, we draw our literature from the four areas of sustainability, social enterprise, sustainable leadership and sustainability culture, brand development, and knowledge management. In addition, we review several key relevant theories to provide a solid theoretical ground for our study. The corporate sustainability literature suggests that a sustainable enterprise considers itself as an entity operating within the society and that an enterprise cannot be sustainable if the society is not sustainable [

8]. This suggests that a sustainable enterprise is a business enterprise that has a mission to develop the society, a similar concept to that of social enterprise.

Our present study adopts the corporate sustainability concept as defined by Wilson (2003) [

15] because it is well grounded in other related concepts of sustainability, sustainable development, social responsibility, and stakeholder and accountability theories. As a result, Wilson (2003) [

15] define corporate sustainability as a set of notions on corporate management that still acknowledges the need for growth and profitability but places a much greater emphasis on the triple bottom line results and the public reporting on them.

Despite no commonly agreed definition for social enterprise [

16], its nature and expected function are widely acknowledged by various groups of people. To some, social enterprise is treated as a concept where businesses maximize long-term profits to spend on sustainable development initiatives. To others, it means a concept of commercial, but non-profit organizations passionate about social performance and clear about their own social missions [

17]. Although there are various definitions, both extremes are clear about their higher-order purpose of delivering benefits to the society. For a discussion purpose, we adopt the definition given by Yong and Lecy (2014) [

18] that a social enterprise is an enterprise that is operated with a prime mission to improve the society at large.

Alter and Dawans (2006) [

13] point out that such factors as leadership, culture and financial viability are required to achieve sustainability of social enterprises, which is consistent with findings from other corporate sustainability studies [

10,

19,

20]. Therefore, both scholars support the holistic approach for achieving a sustained social value. Such a holistic approach should happen at the level of culture, operations, and finance to allow social enterprises to arrive at a sizable scale and social impact. Ketprapakorn and Kantabutra (2019) [

21] would agree with this belief as their study found that organizational leadership and culture play an integral role in sustaining an enterprise in Thailand. They have reported that corporate values of virtues, social and environmental responsibility and innovation are necessary to sustain an enterprise [

21]. In addition, they have revealed that leaders in their sample firms acted as models according to these values to echo the values in their employees’ minds all the time.

Nevertheless, corporate sustainability is also subject to contextual differences. One approach working in Europe might not be working in Asia, which is the focal region for this present study. For the last few decades, the Asian economy has expanded rapidly. Given the rapid regional growth and unpredictable business environment, Asian corporate leaders, including those in the healthcare sector, have been searching for an effective approach to corporate sustainability for their businesses [

4,

19]. Most of the ideas, concepts and approaches, such as corporate social responsibility, triple bottom line, and green supply chain, are not holistic and derived from the Western world. Although Wilson (2003) [

15] has outlined some broad directions to ensure corporate sustainability, they do not provide a holistic solution that corporate leaders look for. The only holistic approach to corporate sustainability found is the Sustainable Leadership concept (e.g., Rhineland leadership and Honeybee leadership), but it is still derived from the Western world which was found not perfectly applicable in the Asian context e.g., Refs. [

10,

20] as the Asian context is so diverse culturally, socially, politically, economically and geographically [

22], indicating an area for further investigation in the present study.

With growing interest among scholars in the corporate sustainability field, researchers globally have been searching for an alternative way to lead business organizations toward sustainability, including improving natural resources utilization e.g., Ref. [

23]; integrating the sustainability aspect with the vision-based leadership paradigm e.g., Ref. [

24]; or introducing new leadership ideas such as ethical leadership e.g., Ref. [

25], the Stakeholder theory [

26] and responsible leadership [

27].

In an attempt to find a holistic approach to organizational sustainability, Andy Hargreaves and Dean Fink (2003) [

28] were among the first who launched a concept of sustainable leadership. Seven principles were set out and initially planted in the educational sector. In 2005, Gayle Avery [

8] introduced another business version of sustainable leadership known as Rhineland Leadership whose core is affiliated with an organization’s long-term sustainability and relationships with various interest groups in addition to shareholders. The approach advocates 19 elements in order to sustain an organization. Years later, the Rhineland Leadership approach was elevated to another new approach called Honeybee Leadership consisting of 23 elements [

29].

In Thailand, a philosophy called Sufficiency Economy is seen as a holistic approach to lead a company toward sustainability [

30]. Although this philosophy is native to Thailand, it has been increasingly recognized internationally [

31]. Since its introduction, researchers [

18,

32,

33] have adopted the philosophy to examine corporate sustainability in various industries in Thailand to find that it is applicable to the Thai context. There have been a few attempts to operationalize the Sufficiency Economy philosophy in business organizations [

33,

34]. Although findings from these few studies reveal similar corporate sustainability predictors, they still need further refinement to ensure a reliable set of such predictors so that it can be replicated elsewhere, another objective of the present study. In addition, the existing literature on corporate sustainability is predominantly empirical, there are several calls e.g., [

21] to develop a solid theoretical foundation to guide future developments in the corporate sustainability field, the other objective of our present study. In terms of corporate sustainability research in the healthcare services sector in Thailand, there have been very few studies [

4], indicating another research gap for the present study. Therefore, from here on, we focus our review on the theoretical and empirical literature related to the Sufficiency Economy philosophy.

After the Asian economic crisis in 1997, the Sufficiency Economy philosophy was reiterated by His late Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej as a holistic approach to sustainable development for Thailand and a guideline for people to stay away from unsustainable practices that caused the economic crisis [

35]. As opposed to the Anglo/US approach of short-term maximization of shareholder value [

24], the Sufficiency Economy philosophy promotes the middle path with a need for built-in resilience as an alternative development strategy that balances among the social, environmental and economic domains of development so that the nation can effectively encounter with the globalization forces.

The adoption of the Sufficiency Economy philosophy demands great care in planning, applying knowledge and implementing the plans [

36]. Moreover, it requires people to be honest and ethical while living their lives perseveringly, harmlessly and generously. Indeed, the philosophy acts as a guide for people at all levels to conduct their lives virtuously. It can be applied to business organizations [

4]. Businesses which integrated the Sufficiency Economy philosophy with their operations enhanced their competitive advantage through products and processes that are environmentally and socially corrected [

33]. Eventually, these sustainable business practices turn into the integrity of brand and reputation, and improved social, economic and environmental performance [

37].

The Sufficiency Economy philosophy emphasizes ethical behaviors toward others. In a corporate setting, it means holding a firm accountable for anyone, not only shareholders or owners, who could be directly or indirectly affected by its operation in the short and long run [

34]. This is consistent with the literature on corporate governance where the focal concern is to add value to as many organizational stakeholders as is possible [

38]. Many companies have committed to codes of corporate governance [

39]. They conform to law and regulation and protect the interests of minority shareholders. They adopt the principles of honesty, the rule of law, transparency, and accountability. Indeed, both the Sufficiency Economy philosophy and the corporate governance concept suggest that a firm needs to take a more responsible and ethical role in its societal context by focusing on satisfying various demands of individuals and organizations with a stake in the firm.

The Sufficiency Economy philosophy approach is not only compatible with the corporate governance system, but also adds two more dimensions [

39]. First, the approach provides a process for planning and executing corporate strategies with sustainable profit and social benefits as the main goals. Moreover, the principles of moderation, reasonableness and immunity provide a holistic framework for crafting sustainable strategies. These strategies are built upon internal protection against risks and proper governance, by taking into consideration the impact on community, society and environment. Second, the Sufficiency Economy philosophy approach demands a level of corporate commitment that goes far beyond rules and codes. Companies adopting the philosophy build their corporate philosophy around the Sufficiency Economy principles. They also communicate the philosophy with their stakeholders, including employees, to create a corporate culture that is conducive to long-term corporate success [

21].

Based on the literature, the following corporate sustainability practices and their consequences are derived. The corporate sustainability practices are Perseverance, Geosocial Development, Moderation, Resilience, and Sharing, while the consequences of adopting them are social, cultural, environmental, and economic outputs. Internationally, brand equity is also considered as an output from adopting corporate sustainability practices. Therefore, we adopt brand equity as an additional output in our present study.

Since the literature specific to the Sufficiency Economy philosophy in business organizations is predominantly empirical, we form a solid theoretical foundation for the present study by drawing necessary theoretical supports for each of the corporate sustainability practices from relevant, internationally recognized theories, including the Self-determination theory, the Stakeholder theory, the Sustainable Leadership theory, the Complexity theory, the Knowledge-based theory, the Dynamic Capabilities theory, and the Knowledge Management theory. As a matter of fact, we are indeed developing a coherent theory of Sufficiency Economy in business, built upon the existing key theories, as the basis for our study. Each corporate sustainability practice is discussed in detail below.

2.1. Perseverance

Perseverance is a virtue, an underlying condition of the philosophy of Sufficiency Economy. In the broader literature, perseverance is defined as continued goal-striving despite adversity [

40]. Clearly, perseverance is needed not only for early-stage companies, but also more established ones as one may run into unexpected difficulties and challenges, which requires an iron will and more time to resolve than initially expected. Gelderen (2012) [

41] introduces a perseverance model including four broad strategy categories including, (1) strategies affecting adversity itself, (2) strategies that change the way adversity is perceived, (3) strategies that reframe the aim that adversity has made difficult to attain, (4) strategies that help to increase self-regulatory strength. Indeed, perseverance plays a fundamental role not only in starting up a firm, but also to ensure the firm’s success in the long run [

4,

9,

41], particularly when the business environment is constantly changing.

The theoretical rational behind Perseverance can be explained by the Self-determination theory [

42]. The theory is related to the motivation behind options people choose without being influenced and interfered externally. It emphasizes self-motivating and self-determining behavior. The theory assumes that persistent positive features are of human nature. Individuals also have innate psychological needs that form the foundation for self-motivation and personality integration.

Self-determination theory [

42] asserts that all human beings have three human needs to satisfy: autonomy, competence and relatedness. More precisely, individuals need to feel that they are autonomous and competent [

43]. They also need to enjoy fulfilling relationships [

43]. Self-determination theory asserts that naturally all individuals are motivated. According to the theory, motivation can be categorized into controlled motivation and autonomous motivation [

44].

Controlled motivation comprises both external regulation and introjected regulation. External regulation is when one’s behavior is driven by external contingencies of reward or punishment. On the other hand, introjected regulation is when the action is regulated, partly internalized and invigorated by such factors as contingent self-esteem and avoidance of shame. Controlled individuals are under pressure to think, act or feel in certain different ways. On the other hand, autonomous motivation is composed of both intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. However, the extrinsic motivation only includes the types in which individuals have associated with the value of an activity. They often have incorporated the value into their sense of self. The individuals, autonomously motivated, experience a self-endorsement of their actions. Both types of motivation direct and invigorate individual behavior, the opposite of amotivation.

Interestingly, Self-determination theory relates autonomous motivation to improved persistence, performance, social functioning, and physical and psychological well-being [

45]. However, the persistent, proactive, and positive tendencies of individuals are not always apparent [

42] because they can be hindered when the three basic human needs are not fulfilled. Moreover, the organizational context is often cited as the reason these basic human needs are dropped, therefore deterring corporate sustainability. On the other hand, if the three basic human needs are fulfilled, ideal function and growth are enhanced, leading to improving corporate sustainability.

In essence, pursuing some goals towards personal growth, relationships, community, and health provides greater satisfaction of psychological wellbeing than pursuing other goals related to wealth, recognition and image [

46]. As a matter of fact, the pursuit of these other goals undermines sustainable wellbeing [

44,

47,

48,

49]. Intrinsic motivation and aspirations refer to personal growth, affiliation, community contribution and health, while extrinsic ones refer to wealth, recognition and image [

48]. People who are intrinsically motivated are motivated by the enjoyment of the activity they do, as opposed to the outcomes [

50]. Extrinsically motivated people are motivated by the achievement of goals driven by external controls such as reward or punishment [

51]. Organizational sustainability theorists such as Ketprapakorn and Kantabutra (2019) [

21] would agree with this notion as they assert that an alignment between corporate values and individual employee values is needed to create intrinsic motivation in an organization, therefore ensuring organizational sustainability. In the context of corporate sustainability where corporate leaders often encounter great difficulties in leading their enterprise, the Self-determination theory explains the behaviors of corporate members who persist to carry on what needs to be done, regardless of influence from other people or situations. Self-motivated individuals always find a reason and strength to carry out a challenging task, without giving up or requiring another to motivate them. Theoretically, they do so because they share a higher-order purpose of their organization, therefore always being intrinsically motivated to carry on, despite great difficulties. Such on-going, intrinsic motivation in human beings leads to perseverance, which in turn enhances corporate sustainability.

2.2. Geosocial Development

Although Geosocial Development is not explicitly mentioned as part of the Sufficiency Economy philosophy, it is considered relevant because the Geosocial Development concept emphasizes the ethical responsibility towards a broad range of stakeholders to ensure sustainable development [

33]. Endorsing the Geosocial Development practice is the Stakeholder theory which highlights moral and ethical values as fundamental attributes of corporate management [

26] to ensure corporate sustainability. Essentially, enterprise sustainability demands a leadership approach highly sensitive toward the interests of a wide range of stakeholders [

52,

53,

54,

55], although taking care of the interests may limit short-term profitability. The Geosocial Development is also consistent with the sustainable enterprise elements [

8] of Stakeholder Focus, and Social and Environmental Responsibility where sustainable enterprises regard investments in stakeholders, including the society and the environment, as bringing them a competitive advantage.

The Stakeholder theory is concerned with a business that takes into account a broad range of stakeholders. The business focuses its efforts and resources on defining and delivering the values of the business. At the same time, it strengthens the business and societal relationships to ascertain the business’s sustainable success. Sustainable profitability of organizations and their survival depend upon their capacity to comply with the economic and social purpose [

56], including creating and distributing reasonable wealth or value. They do so to ensure that their stakeholders remain a part of their corporate system. From an organizational strategy perspective, an organization is a group of inter-reliant relationships between stakeholders [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. The model of strategic stakeholder management by Berman et al. (1999) [

65] is based on the evidence that firms seriously take into consideration the stakeholders’ concerns because they believe doing so enhances corporate financial performance. This instrumental approach of Stakeholder theory is constructed upon the Agency theory, the Transaction Cost theory, and organizational behavioral ethics [

62] to ensure long-term sustainable success.

Freeman and McVea (2001) [

66] formulate a framework of four distinct lines of organizational management research, as demonstrated by Freeman (1984) [

67]: (1) strategic organizational planning; (2) Systems theory; (3) corporate social responsibility; and (4) Organizational theory. These four distinct lines can well explain how focusing on satisfying stakeholder demands leads to corporate sustainability.

First, within the strategic organizational planning line, successful strategies do not only respond to the maximization of one stakeholder group’s position to the detriment of the others. On the contrary, effective strategies respond to the integration of all stakeholder interests. This notion is grounded upon the Systems and Organizational theories. Both theories regard organizations as open systems interacting with diverse third parties. Therefore, collective strategies that make the system as a whole complete are needed to ascertain their own survival. Although corporate social responsibility is not regarded as a formal theory, it seeks to demonstrate the necessity of developing strong and trusted relationships. Also, a good reputation with all stakeholder groups outside the organization is to be maintained for its sustainable success.

The purposed destiny of the Stakeholder theory is to replace the dominant theory of the Firm, or the economic model of the firm [

68] where the only goal is to maximize short-term profitability for shareholders. The Stakeholder theory seeks to provide attitudes and organizational practices for the firm to survive, despite social and economic crises, and to prosper in the long run [

69]. The influence of a broad range of stakeholders in corporate strategy demands responses on behalf of the firm, reflecting the potential, threatening or cooperating power of each stakeholder within a context of mutual interests and benefits.

In the corporate sustainability context, companies, adopting the Stakeholder theory approach, try to satisfy various demands of a wide range of stakeholders by balancing the demands among them. In theory, such a balance in turn brings about long-term stakeholder relationships which help the companies to ensure long-term, sustainable success.

2.3. Moderation

Moderation is closely related to the notion of sufficiency [

70]. The word for sufficiency in Thai and English suggests two meanings: sufficient in the sense of not too much, and sufficient in the sense of not too little. The word conveys the notion of a middle way between want and extravagance, between impossible dreams and backwardness, implying both self-reliance and frugality. Moderation is at the very core of Buddhism [

71,

72]. Based on the Buddhist economics model, an economic activity is regulated by a condition that it is geared towards achieving sustainable well-being, as opposed to maximum pleasure emphasized by the mainstream economic thinking [

71] where maximizing short-term profitability is key. Under this paradigm, there is no overproduction or overconsumption, improving an overall sustainability prospect. In the prevailing economic thinking, human desires are unlimited and regulated by scarcity, while in the Buddhist economics thinking, the desires are unlimited also, but regulated by a moderation value and the ultimate goal of sustainable well-being. Another theoretical point of view in support of Moderation in ensuring sustainability is the concept of “optimal consumption” [

72]. Optimality is guided by a preference of “chanda” (motivated by well-being), and not a preference for “tanha” (stemming from craving). This concept is also related to sustainable, responsible consumption.

As a theoretical foundation for Moderation, the Sustainable Leadership theory offers a set of principles that can assist organizational leaders to sustain their organization [

10,

73,

74]. One of the principles is long-term orientation which can explain how being moderate impacts corporate sustainability. While the prevailing leadership approach focuses on short-term results, a key practice in sustainable enterprises is to the contrary. They take a long-term view by balancing the long- and short-term demands. Such a balance is challenging, but possible, to achieve when short-term considerations often forgo long-term goals. To maximize profits now, many firms have indeed mortgaged their future long-term position [

75]. Sustainable prosperity needs a long-term view. It is this long-term perspective that enables firms to outperform their counterparts focusing on short-term goals [

76]. The long-term view affects all aspects of sustainable enterprises, ranging from corporate strategy and work processes to the management of stakeholder relationships [

10]. Sustainable enterprises view themselves as being entrusted with the sustainable well-being of themselves for future generations.

Espousing the long-term view, sustainable enterprises manage to avoid uncertainty and abrupt changes [

10]. In particular, the long-term view affects corporate sustainability by minimizing trouble when executives leave, which is frequently a case in less-sustainable companies taking a short-term view. In sustainable enterprises, executives are accountable for the short- and long-term consequences of their decisions, allowing for long-term planning and investment to take place through designing compensation schemes based on the long-term corporate performance.

Theoretically, Moderation enhances the corporate sustainability prospect by enhancing organizational capacity to endure difficult economic and social crises via the process of careful, reasonable decision-making involving taking into consideration long-term and short-term consequences on the enterprise and its stakeholders [

10]. Moderation also leads to prudent management of operational and policy risks and available opportunities, making the enterprise less prone to the impact of ad-hoc hostile events [

10].

2.4. Resilience

According to the Sufficiency Economy philosophy, Resilience is drawn from the need to develop immunity for oneself. Resilience is an important attribute of self-reliant individuals, families and communities [

77]. Such individuals and communities demonstrate resilient traits when confronted with adverse situations and calamities that challenge their ability to survive. In the field of organization studies, resilience goes much deeper than the more limited sense of bouncing back from crises. It really is the organization’s capability to dynamically reinvent its business model as the environment and circumstances change [

78], suggesting resilience as a process which in turn attracts scholars to investigate the notion of resilient systems. Essentially, resilience is a dynamic set of conditions, as embodied within a system. Therefore, the concept of organizational resilience makes more sense when considered under the Systems theory [

79]. The resilient systems promote self-reliant growth and sustainable development [

77].

In the business setting characterized by great complexity and uncertainty, resilient companies can endure both social and economic difficulties. To be able to do so, they anticipate and prepare for change and continuously develop innovation in services, products and processes, consistent with the practices found in sustainable enterprises [

8]. Increasing corporate resilience also assists a firm to identify its “keystone vulnerabilities” and “multiple capabilities”, and to prioritize them when formulating strategies and plans [

80]. Resilience increases awareness of a firm’s operating environment and provides the ability to cope with threats and challenges [

80] while aiming for a promising future.

As a theoretical foundation for Resilience, Lewin’s theory of Complexity (1999) [

81] comprises five assumptions. First, humans are organisms, not machines, suggesting that they can interact and make decisions involving change in multiple ways. Second, a consequence of the interaction between the agents mutually affecting one another is the origin of organizational emergence. Third, small changes bring about large effects. Organizational leaders are required to adapt their human resources and institutions accordingly. Lastly, emergence is certain, but it is uncertain as to what the outcome will look like.

In several ways, the theory of Complexity compliments the Sustainable Leadership theory. Both recognize the non-static, non-linear nature of the world, and the required control in operating human organizations. In such a complex world, there is a need for more organizational self-monitoring and self-regulation [

82]. Complexity theorists assume that businesses are multifaceted, adaptive systems, and that human organizations emerge, self-organize, and adapt to deal with problems when they encounter disequilibrium and are close to the edge of chaos [

83]. To survive, the viability of the complex systems must be reinforced by ensuring a balance of autonomy and organizational cohesion. A suitable balance between the autonomy of subsystems and organizational cohesion is essential for organizational sustainability [

83].

Furthermore, corporate leaders can best promote sustainability by balancing the ability of self-managing, self-leading individuals at different operational levels, at the same time maintaining overall organizational coherence [

83]. The essence of promoting independent thought under suitably structured direction is emphasized [

84] by developing leaders who understand the importance of sufficiently controlling people and processes. To do so, they only create structures needed for inhibiting or redirecting ideas inconsistent with corporate missions or those possibly damaging corporate functions [

84].

Lending support to Resilience, the Complexity theory suggests that what needs to be done is preparing staff for changes and transforming them into interactive agents to cope with emergent problems and issues. Staff as adaptive agents in complex systems are also the medium of information and knowledge transmission, and their individual learning can lead to organizational development and increase its capacity for dealing with challenges of internally and externally changing environments, thereby enhancing corporate sustainability.

2.5. Sharing

Sharing is a virtue, an underlying condition of the philosophy of Sufficiency Economy. The term sharing is defined in various ways. It can be considered as an act to give and receive [

85]. Sometimes, sharing suggests goods can be shared to efficiently utilize resources [

86]. Sharing is also linked to passing on feelings, experiences, ideas, or knowledge [

87]. In a business organization context, it primarily means sharing knowledge internally among members and externally with stakeholders. In the Sustainable Leadership literature e.g., Refs. [

8,

10], knowledge sharing is required for a sustainable enterprise, and knowledge sharing usually leads to organizational innovation.

Internally, knowledge sharing, as a process of interaction involving knowledge, experiences, and skills of organizational members working in an organization, helps organizations to identify best practices and promotes new ideas and organizational learning [

88,

89]. Innovation takes place through sharing of the knowledge resources of an enterprise with other stakeholders [

90,

91]. The fact that a relationship network that integrates various intellectual assets exists unavoidably affects the value creation and delivery of the enterprises participating in the network [

92]. As a theoretical foundation for sharing, the Knowledge-based theory states that knowledge is considered as the most important strategic resource [

93]. Theoretically, knowledge management leads to the integration of organizational, specialized knowledge [

94], an opposite view from the previous literature that the organization’s main role is to apply knowledge, as opposed to creating it [

95]. When theorists of the Knowledge-based theory refer to “knowledge”, they mainly refer to knowledge held in employees’ heads (implicit knowledge), as opposed to one coded in an information system [

96]. Knowledge in this sense is unique and difficult to imitate or purchase as it is context-specific, experience-based and part of a company’s unique procedures and routines. Therefore, implicit knowledge, if well developed and managed, can lead to long-term, sustainable competitive advantage of the firm.

Also endorsing the Knowledge-based theory and thus Sharing, strategy theorists formulate the Dynamic Capabilities theory [

97,

98,

99]. This theory emphasizes that an enterprise needs to develop and renew its external and internal knowhow to maintain sustainability of its competitiveness. The core of this theory is the organizational capacity to continuously renew its competencies in response to the often-abrupt environmental changes [

100]. To do so, based on the Knowledge Management theory, new knowledge is to be created through deliberate sharing of knowledge within enterprises, between enterprises and with external stakeholders [

101]. By managing knowledge, enterprises can ensure their continuity and enhance profitability [

101]. Moreover, their organizational efficiency can be improved, which positively impacts their industry position since they work more intelligently in the industry. Knowledge enterprises can enhance the communication and synergy between knowledge workers and ensure they stay to contribute to corporate success.

In addition to the five corporate sustainability practices, sustainability performance is to be explained since theoretically corporate sustainability practices improve sustainability performance. In the present study, we define sustainability performance as comprising the triple bottom line results and brand equity. The triple bottom line results incorporate social, environmental and economic outputs. Each is discussed below.

2.5.1. Social, Environmental, and Economic Outputs

Regardless of its seeming importance, some difficulty and controversy exist on how to translate the concept of corporate sustainability into business guidelines and practices. Given its sophistication, corporate sustainability is frequently regarded as implementing the Triple Bottom Line (TBL), as the balance among the three dimensions are integral to ensuring long-term prosperity [

102,

103]. Recently, it has been well recognized that economic success is not the sole indicator for evaluating corporate, long-term resolution. Sustainable success is related to successfully fulfilling the needs of corporate stakeholders [

104]. The TBL notion underlines the necessity of balancing economic prosperity, social equity and environmental quality [

105]. In theory, economic development takes place in relation to human beings and the earth. As a consequence, TBL-driven corporations may not be financially profitable in the short run [

106]. Indeed, social, environmental and economic sustainability are required to enable a sustainable development.

The term “social sustainability” has become prominent, as people want to be associated with socially responsible firms. To some, social sustainability means an ethical code of conduct for the survival and growth of the society that can be achieved by a prudent and holistic manner [

107]. To others, social sustainability is also related to management of the society’s resources such as people skills and abilities, their relationships and values [

108]. Social sustainability is also related in some sophisticated ways to environmental sustainability because until the basic needs of the society are met, it is unlikely that companies and governments will sufficiently deal with the environmental issues [

109]. For example, evidence suggests that poverty acts as a barrier to the adoption of green technologies such as solar and wind power generation [

110]. Meeting people’s basic needs is really an integral part of attaining sustainable developmental goals.

In terms of the environment, environmental responsibility is needed to ensure the environmental condition that will forever support human well-being exists forever [

111]. Environmental sustainability is also key to the Triple Bottom Line. To some, environmental sustainability means a condition of balance, resilience and interconnectedness allowing human society to fulfill its needs while not exceeding the capacity of its supporting ecosystems to continue to function to meet the needs of the society [

112]. To others, it means actions and activities that minimize the negative consequences and maximize the positive consequences of human being on the environment via green operations such as continuous assessment of environmental inputs [

113], green product development [

114], and use of renewable energy resources [

115]. In general, it is critical for companies to measure and monitor environmental sustainability on a continuous basis via certain performance indicators such as recycling of waste [

116]; waste management [

117]; sustainable packaging [

118]; and environmental marketing [

119].

Moreover, many executives realize that the TBL approach can be adopted as a means to increase value for their products and services [

120], emphasizing the critical role of TBL in improving corporate sustainability prospect. To many, TBL is understood as the main proxy to measure corporate sustainability performance [

121,

122]. As a result, the TBL approach suggests companies to report their social, environmental, and economic performance outputs as measures for corporate sustainability [

123].

2.5.2. Cultural Output

In addition to the TBL results, the literature on Sufficiency Economy philosophy suggests an additional sustainability output of cultural performance [

30]. Culture plays an important role in ensuring sustainable development because it outlives any one individual [

108]. Culture is the way in which values are expressed and applied practically in daily life of a society, including underlying beliefs, values, aspirations and practices [

124]. Culture also includes processes and mediums through which values are preserved and transmitted from one generation of the society to another [

124]. In order to achieve the TBL goals of environmental, social and economic outputs, a set of sustainability values and behaviors should be developed among organizational members [

125]. Since a sustainable culture is part of a sustainable society, the natural, economic, social, and culture environment must be taken into account in any action toward sustainable development [

126]. If the culture in a society is not well integrated, other components of the society will also disintegrate as a result [

124]. Indeed, the cultural dimension of sustainability is to ensure the continuity of sustainability values relating the past, present and future [

127], a concept that is often overlooked by corporate sustainability studies.

Considering a business organization as a society, it can be drawn that the culture varies from the national culture to organizational culture. Sustainable enterprises are featured by a strong organizational culture [

4,

10] with a consensus among organizational members about assumptions, values and beliefs [

128]. Such an organization-wide consensus creates consistency in views, individual interpretations, and actions among organizational members, all of which lead to fostering united purpose and action [

129]. With such underlying sustainability values as social and environmental responsibility, and innovation [

21], this organizational strength improves financial performance [

130], due to improved coordination and control, increased morale, and alignment among organizational members [

131,

132,

133,

134]. A strong and productive organizational culture brings about a form of intellectual property or an intangible asset [

135]. A positive culture works as an intangible asset, while a negative culture works as a drag on performance, potentially leading to organizational decline or demise. Many organizations develop a set of sustainability values to foster a strong organizational culture [

21], which brings about better sustainability performance [

18].

2.5.3. Brand Equity

In today’s fierce market, competitiveness through tangible, functional benefits, is no longer sustainable. That is a reason an organization’s brand, considered as functional and emotional benefits, is regarded as fundamental to organizational sustainability. Increasingly, brand equity is regarded as a consequence of corporate sustainability. It represents corporate power and reputation in the marketplace and ultimately, due to its impact on customer perceptions and behaviors, influences corporate financial performance [

135,

136]. The literature on sustainable enterprises emphasizes corporate responsibility and moral commitment for various stakeholders [

29,

37,

137] by assuming that doing so leads to strong brand integrity and reputation, a high level of customer satisfaction, solid financial performance, and as a consequence improved long-term value for a wide range of stakeholders, including owners and shareholders. Sustainable enterprises pay great attention to multiple stakeholders and their relationships with them by recognizing the stakeholders’ concerns and needs [

137,

138]. These strong bonds are built upon mutual trust and respect, support, as well as sincere understanding. They do so to avoid social crises and improve society [

137]. According to Aaker (1992) [

139], brand equity adds value to the firm by enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of marketing programs, brand loyalty, prices and margins, brand extensions, trade leverage, and competitive advantage of the firm. While others [

140] have stated that an incremental value that the brand name adds to a product determines brand equity, to Aaker (1992) [

139], brand equity is defined as a grouping of brand assets and liabilities, associated with the name and symbol of the brand. This grouping can deduct from or improve the value delivered by a service or product. Certainly, a firm’s corporate reputation perceptually should represent its past actions as well as those in the future and reflects the firm’s overall appeal with regards to all major stakeholders as compared to its competitors [

141]. Furthermore, some researchers [

142,

143] have asserted that the total value that a brand adds to one of their main products determines brand equity. The brand equity model comprises brand loyalty; brand name awareness; perceived brand quality; and brand associations, perceived quality, and other proprietary brand assets [

139]. These dimensions are part of the process of building a strong brand [

144,

145,

146].

Based on the literature review above, the independent and dependent variables are identified. Their terminologies, contributing measured items and descriptions are shown in

Table 1 below.

Accordingly, the following research questions are derived.

Research Question 1: What are the statistically significant predictors of corporate sustainability in a healthcare context in Thailand?

Research Question 2: Do the predictors create positive effects on corporate sustainability in a healthcare context in Thailand?

Research Question 3: What is the relative importance of the predictors?

Based on the research questions, we formulate a structural model, a set of hypotheses and develop a research methodology to test them, which is discussed in the next section.

2.6. Research Framework

Based on the literature review above, relationships appear to exist between the corporate sustainability approach as informed by the Sufficiency Economy philosophy and the consequences of adopting it. Since our present study is original with no standard set of measures available, we have empirically derived a set of independent and dependent variables from our exploratory factor analysis, using data from our sample healthcare services provider in Thailand, to be introduced in the following section.

As a result of our exploratory factor analysis, a structural model (

Table 1), specific to the sample healthcare services provider, is derived. The structural model comprises four independent constructs and three dependent constructs. How each of the constructs and its measured items are derived is discussed in the Measured Items section below.

Accordingly, a set of 12 hypotheses is derived for testing. The structural model suggests that the corporate sustainability practices of Leadership, Resilience Development, Sharing and Stakeholder Focus directly lead to enhanced sustainability performance outputs of Brand Equity and Socioeconomic and Environmental Performance.

We would like to note that instead of having two output constructs of social and economic performance, the present study has only a combined one called Socioeconomic Performance as perceived by the respondents at the social healthcare services provider. The term Socioeconomic Performance, as a combination of cultural, social, environmental, and economic outputs, is supported by Brüderl and Preisendörfer (1998) [

147], who argue that the survival of the society is the minimum criterion for corporate performance as a corporation is an entity within the society. If society cannot exist, nor can the firm. Therefore, rather than using only economic performance as firm performance, one should incorporate social survival in it, the consequence of which is called socioeconomic performance. This view is also consistent with the literature on sustainable enterprise e.g., Refs. [

8,

10].

Each of the 12 causal relationships is supported by the literature as discussed below. The literature review clearly indicates that corporate sustainability practices lead to enhanced brand equity [

29,

147], a relationship to be hypothesized in the present study. To elaborate the relationship, firms having sustainability embedded in their corporate vision and realizing such a vision are sustainable [

148] because they ensure that their operations deliver both functional benefits and psychological benefits or “happiness” to a broad range of stakeholders. In turn, stakeholder-perceived benefits and happiness lead to different levels of stakeholder–company relationship quality, resulting in enhanced corporate reputation and brand equity [

148]. Although brand equity is typically evaluated by stakeholders of a company, it has become increasingly critical as a consequence of adopting corporate sustainability practices [

29,

149]. Given that the Leadership, Stakeholder Focus, Resilience Development and Sharing practices are considered as corporate sustainability practices, the following directional hypotheses are formed.

H1. The Leadership practice is directly predictive of enhanced Brand Equity.

H2. The Stakeholder Focus practice is directly predictive of enhanced Brand Equity.

H3. The Resilience Development practice is directly predictive of enhanced Brand Equity.

H4. The Sharing practice is directly predictive of enhanced Brand Equity.

In addition, the literature review [

8,

10] has indicated that sustainable enterprises are genuinely concerned for the society and the environment. More often than not, social and environmental responsibility is integrated in their products and services allowing them to be competitive [

10,

40]. As introduced earlier, unique for the present study is the combination of culture, social, environmental, and economic performance outputs. Based on our exploratory factor analysis result, a combination of cultural, social, environmental, and economic performance outputs is perceived by employees as a single construct called socioeconomic performance output, which is not a surprise as it is generally agreed that economic outputs and the delivery of social value comprise social enterprise performance [

150]. Measuring the performance solely based on the economic context is also limiting and not sustainable. Firms must develop sustainable social relationships with their surrounding communities and with society at large [

90,

91], the logic underlying the TBL paradigm as an approach to sustain companies [

123]. For this reason, the social performance is defined as a dependent variable of the present study together with the economic performance. It can be drawn that Leadership, Stakeholder Focus, Resilience Development and Sharing practices, as corporate sustainability practices, lead to improved socioeconomic performance. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formed.

H5. The Leadership practice is directly predictive of enhanced Socio-economic Performance.

H6. The Stakeholder Focus practice is directly predictive of enhanced Socio-economic Performance.

H7. The Resilience Development practice is directly predictive of enhanced Socio-economic Performance.

H8. The Sharing practice is directly predictive of enhanced Socio-economic Performance.

In terms of environmental performance, a number of green issues have emerged as key components in a global call to hold companies socially and financially responsible for their decision to act or not to act. In general, environmental sustainability deals with how the needs of the present can be met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, in reference to natural resources and the natural environment [

151,

152]. Moreover, corporations that invest and perform well in managing the environment are typically more competitive [

153], because increasingly environmentally conscious customers tend to be comparatively happier with a company that is known to be environmentally friendly. The company with that image can retain its existing customer base and acquire new customers that result in more competitiveness. That is the reason sustainable companies view environmental responsibility as bringing them a competitive advantage [

8], as opposed to costs. It can be explained that companies that invest and perform well in environmental management can avoid costs of environmental damage, create an attractive brand, and minimize capital cost [

154,

155]. Through this process, the companies can equip themselves with a competitive advantage, which increases their market share and financial outputs, both of which lead to enhancing corporate sustainability prospect. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that Leadership, Stakeholder Focus, Resilience Development and Sharing practices, as corporate sustainability practices, lead to improved environmental performance. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formed.

H9. The Leadership practice is directly predictive of enhanced Environmental Performance.

H10. The Stakeholder Focus practice is directly predictive of enhanced Environmental Performance.

H11. The Resilience Development practice is directly predictive of enhanced Environmental Performance.

H12. The Sharing practice is directly predictive of enhanced Environmental Performance.

The next section introduces our sample social healthcare services provider, Theptarin Hospital.

3. Theptarin Hospital

Theptarin Hospital is a hospital located in Bangkok, Thailand, founded by the strong determination of Professor Thep Himathongkam in 1985 to serve the society as a social healthcare enterprise. For the past three decades, it has provided holistic care to more than 300,000 patients. Throughout Thailand and the neighboring countries, the medical professionals from Theptarin Hospital are recognized as among the best for the treatment and prevention of endocrine disorders. It is the only private hospital in Thailand designated by the World Diabetes Foundation as a learning center.

According to Kantabutra (2011) [

4], Theptarin Hospital has a coherent organizational culture deeply rooted in the history of the hospital. This strong organizational culture is a result of the founder’s leadership, determination and vision which have inspired people around him. Over time, the founder’s social service values are transferred to Theptarin professionals, who take great pride in servicing society, a core value at the hospital [

4]. Although Theptarin Hospital is a private hospital, the founder’s teaching spirit continues, forming the corporate culture at Theptarin. It is indeed similar to the culture of a medical school, characterized by research and continuous improvement. Physicians, nurses and other associated medical professionals at Theptarin Hospital were frequently referred to as ‘professor’ [

4].

Historically, the Thai government only focused on the treatment and prevention of acute diseases such as iodine deficiency disease. Therefore, medical schools only trained medical personnel in this area. Given its focus on chronic diseases, Theptarin Hospital encountered a shortage of diabetes care professionals. As a consequence, it decided to invest heavily in developing its own associated medical personnel, although at that time there was no demand for diabetes care given the fact that the public was not aware of diabetes. Recently, the hospital has worked with many government agencies and other partners to educate the Thai public about diabetes. Through this, a demand for diabetes care has been generated.

We choose Theptarin Hospital as a case study for testing the model in this present study because of several reasons. First, the hospital is unique among private hospitals in Thailand as it acts as a social enterprise. As a matter of fact, it is the only one acting so. The hospital has long been devoted to improving the society since its inception. As one of the present study’s objective is to examine if a social enterprise can be sustainable, we choose the hospital because it is also considered as a sustainable enterprise [

4] as it met 15 out of the 19 Sustainable Leadership elements. Also, as a test of sustainability, Theptarin Hospital encountered great economic difficulty during the 1997 Asian economic crisis when its debt, all of a sudden, increased from about 300 million baht (9.4 million USD) to 600 million baht (18.8 million USD) overnight due to the unexpected Baht devaluation. Without a single employee layoff, Theptarin Hospital was able to survive the crisis successfully, given its strong organizational culture, holding them together during that tough time, and support from various stakeholders, including employees and a major lender.

Moreover, since we ask our respondents to answer questions regarding their overall perceptions of the hospital’s operation and sustainability performance, the size of the hospital certainly affects the model. More specifically, as the size of an organization increases, problems of information communication, coordination, interpretation and integration multiply [

156]. Therefore, in our study which requires reliable and valid responses among organizational members on the hospital’s operation and sustainability performance, a smaller organizational size is more suitable.

Most previous studies in the field of organizational studies have measured size by the number of employees [

157]. To be consistent with the previous studies, we also adopt the number of employees as our size measure. According to Caplow (1957) [

158], a medium-size organization is one that is too large to permit the development of all possible pair relationships among members or the recognition of all members by all others. However, it is still small enough so that one or more members may establish pair relationships with all of the others. Theptarin Hospital is considered medium-sized in Thailand because it has between 31 to 200 beds [

159], a suitable size for the type of our study. Moreover, we have permission to collect the data from the hospital as they are willing to participate. This enhances our response rate of close to its population. Importantly, the willingness to participate can ensure an acceptable reliability and validity of the data.

5. Findings

This section presents the findings. To identify statistically significant predictors of corporate sustainability performance and their relative importance, we start by presenting our descriptive statistics and regression analysis results (

Table 4). More specifically, we present critical values needed to answer the research questions.

The hierarchical multiple regression analysis is used to test the 12 hypotheses representing the relationships between corporate sustainability practices (independent variables) and sustainability outputs (dependent variables). The results (

Table 5) indicate that all hypotheses are supported at

p < 0.05, except H7.

It is noted that although the Resilience Development practice is not directly predictive of Socioeconomic Performance, it renders an indirect effect, to be discussed in the mediating effect test below.

In terms of predicting enhanced Brand Equity, the regression analysis results indicate that the four variables of Leadership, Resilience Development, Sharing and Stakeholder Focus practices directly predict enhanced Brand Equity at the 95% confidence level. The regression model comprising the four variables can explain 84.5% of the variation in Brand Equity. Of the four predictors, Sharing (β = 0.371) can explain the variation in Brand Equity the most, followed by Stakeholder Focus (β = 0.250), Leadership (β = 0.187) and Resilience Development (β = 0.129), indicating the relative importance of the four predictors (

Table 6).

In terms of predicting enhanced Socioeconomic Performance, the regression analysis results indicate that the model comprising only three variables of Leadership, Sharing and Stakeholder Focus directly predicts enhanced Socioeconomic Performance at

p < 0.05. The elimination of the Resilience Development predictor reveals greater effects of other predictors on enhanced Socioeconomic Performance. The model comprising the three predictors can explain 78.5% of the variation in enhanced Socioeconomic Performance. Of the three predictors, Leadership (β = 0.416) can explain most of the variation in Brand Equity, followed by Stakeholder Focus (β = 0.242) and Sharing (β = 198) predictors, indicating the relative importance of the three predictors (

Table 6).

Although the Resilience Development predictor is not significant in the full regression model, it may have an indirect effect on Socioeconomic Performance. We adopt Baron and Kenny’s (1986) [

165] procedure to further test for indirect effects or mediating effects. As a result (

Table 7), we observe an increase in the coefficient of determination (R2) of approximately 3% from Regression Models 1 to 2. Additionally, we observe the significant decrease in beta coefficients from Regression Models 1 to 2 for both Stakeholder Focus and Sharing predictors. Essentially, an increase in R2 and a decrease in beta coefficients indicate the mediation effect of the Leadership predictor. It can be concluded that there is an indirect relationship between Resilience Development predictor and Socioeconomic Performance (

Table 7).

In terms of predicting enhanced Environmental Performance, regression analysis results indicate that the four variables of Leadership, Resilience Development, Sharing and Stakeholder Focus directly predict enhanced Environmental Performance at the 95% confidence level. The model comprising the four independent predictors can explain 81.8% of the variation in Environmental Performance. Of the four predictors, Stakeholder Focus (β = 0.302) can explain the variation in enhanced Environmental Performance the most, followed by Leadership (β = 0.234), Sharing (β = 0.207), and Resilience Development (β = 0.158), indicating the relative importance of the four predictors (

Table 6).

7. Toward a Sustainable Social Enterprise Model

This section is our significant contribution to the field of corporate sustainability. Our development of a proposed sustainable social enterprise model is based on the findings from the present study, existing theoretical concepts and previous empirical evidence [

213,

214,

215]. As Weick (1989) [

216] points out, model building requires comparing a diverse set of plausible conjectures, ranging from logical, empirical, to epistemological [

215], so that highlighting takes place to form the substance of our sustainable social enterprise model. To be discussed below, the substance of our sustainable social enterprise model comprises a set of corporate sustainability practice indicators and sustainability performance measures, both derived from the literature.

Since model building, particularly in the social sciences, is an ever-evolving process, our proposed sustainable social enterprise model may be refined, as new theoretical or empirical literature emerges [

217]. Model building is also considered as a new proposition development for future testing [

217]. Therefore, we also formulate a broad proposition, and generalizations are formulated to inform future investigation [

218].

As mentioned earlier, there have been very few studies that have attempted to operationalize the philosophy of Sufficiency Economy in business organizations [

34]. Toward the development of a standard set of corporate sustainability measured items, we compare items of the previous comparable studies and the present study. In the process, we identify measured items that have been found significant across different samples and settings.

Based on the previous studies’ [

33,

34] and our present study’s findings, we identify reliable measured items for corporate sustainability covering the domains of Leadership, Resilience Development, Stakeholder Focus, and Sharing. These measured items have been tested multiple times over the years [

34]; regardless of the differences in industries and samples, the resulting measured items for the domains remain the same. Therefore, at this early stage, we can generalize that these measured items comprise a reliable set of measures for corporate sustainability.

Given their reliability across different samples and industries, future research into corporate sustainability can adopt these measured items and continue testing them in a wide variety of samples and industries to develop a standard set of measures for corporate sustainability. Once we have a standard set with high external validity, we can develop a scientifically sound corporate sustainability index, as opposed to assuming that a balance among the Triple Bottom Line results can ensure corporate sustainability. The derived common measured items for corporate sustainability are shown in

Table 8.

As it is our purpose to build a model for sustainable social enterprise, we therefore adopt the sustainability performance measures derived from the sample social enterprise in the present study. They are measures for brand equity and socioeconomic and environmental performance (see Measured items section).

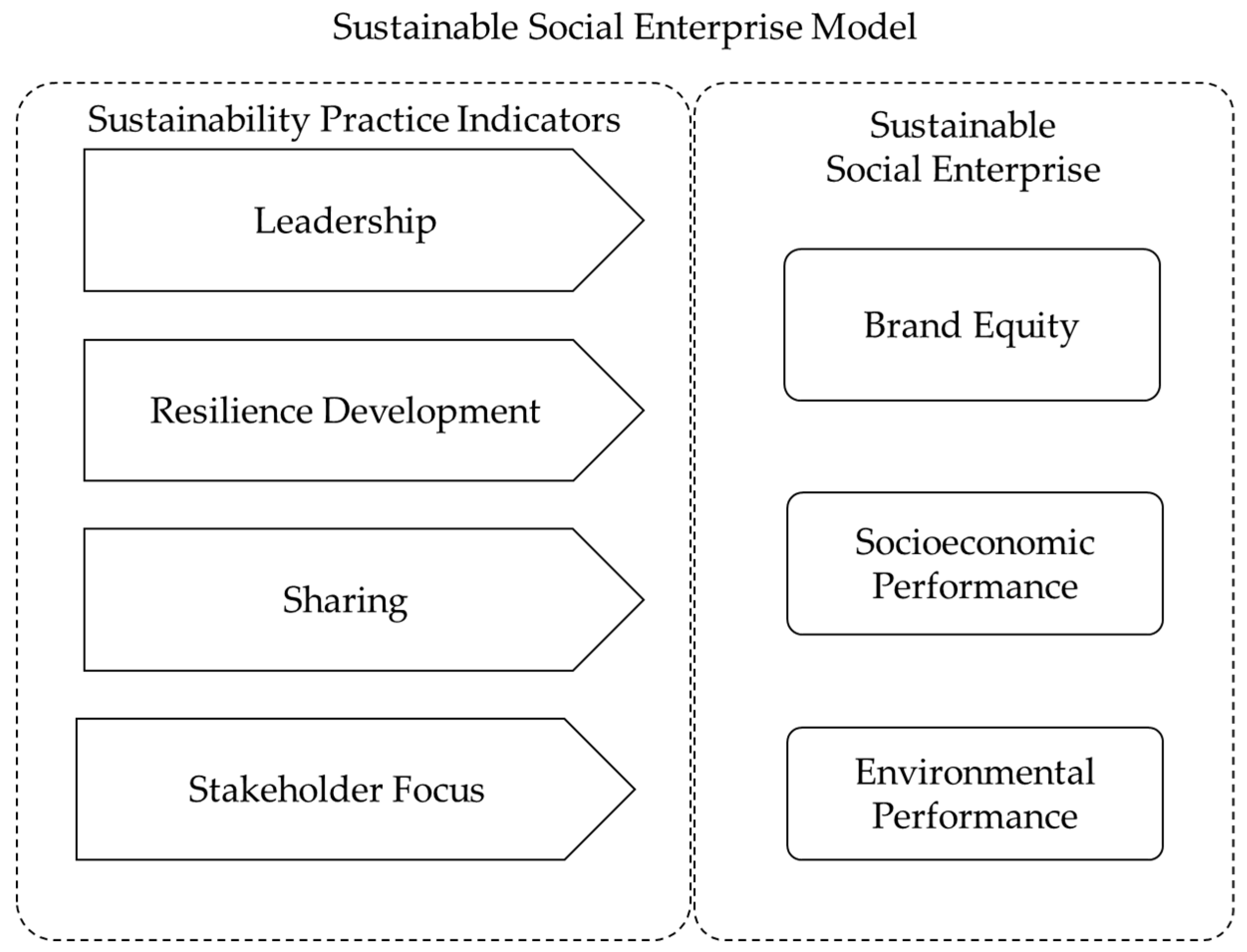

Accordingly, a model for sustainable social enterprise is derived as shown in

Figure 2. Based on the model, each of the four sets of measures for Leadership, Resilience Development, Sharing and Stakeholder Focus can enhance the sustainability prospect of a social enterprise as measured by brand equity and socioeconomic and environmental performance. For a generalization purpose, a broad proposition is developed.

Importantly, it must be noted that our sustainable social enterprise model is both empirically and theoretically sound, addressing the lack of theoretical foundation in the corporate sustainability field. Clearly, the model is built upon empirical evidence from the previous and present studies’ findings. In terms of the theoretical foundation, our model is informed by a number of key relevant theories as discussed extensively in the Background Literature section. To be precise, the Leadership practice is informed by the Self-determination and Sustainable Leadership theories, while the Stakeholder Focus practice is informed by the Stakeholder theory. The Sharing practice is informed by the Knowledge-based, Knowledge Management, and Dynamic Capabilities theories, while the Resilience Development practice is informed by Complexity and Sustainable Leadership theories. These theoretically informed practices are the substance of our sustainable social enterprise model.

Proposition:

The practices of Leadership, Resilience Development, Sharing and Stakeholder Focus predict improvements in the sustainability prospect of a social enterprise.

8. Conclusions

This present study provides answers to the three research questions. First, the statistically significant predictors of corporate sustainability in a healthcare context in Thailand have been identified. They are the predictors of Leadership, Resilience Development, Stakeholder Focus, and Sharing practices. Moreover, all of the predictors directly or indirectly create positive effects on corporate sustainability in a healthcare context in Thailand as measured by Brand Equity and Socioeconomic and Environmental Performance. The relative importance of the predictors on each of the domain outputs is identified. In addition, we have developed a theoretically and empirically sound sustainable social enterprise model for future research. Limitations of the present study, future research directions and managerial implications are discussed in the following subsections.

8.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Like other studies, ours is not without limitations. First, although we have a high response rate, the findings from the present study are from a single healthcare service organization. Moreover, the four corporate sustainability practices and sustainability performance outputs are only perceived ones by employees as opposed to the actual practices and outputs. In particular, our descriptive statistics indicate that our respondents are mainly female and from the operational level, potentially leading to an incomplete view of the organization. More critically, almost half of the respondents have been with the hospital for fewer than 5 years. The period might not be long enough to provide accurate views about the hospital’s practices. Future research should be aware of and address these limitations.

While our present study identifies significant relationships between the corporate sustainability practices of Leadership, Stakeholder Focus, Sharing and Resilience Development and sustainability performance outputs of Brand Equity, Socioeconomic and Environmental Outputs, it does not explain the processes by which each of the practice predictors creates an effect on sustainability performance outputs. Future research should qualitatively explore the processual relationships in different organizational settings and industries to enhance our understanding about them.

As there is always a question whether a social enterprise is a sustainable enterprise, we have developed a model on sustainable social enterprise for future testing. One can easily adopt our model and measured items to test for external validity elsewhere. As a matter of fact, if future research efforts continue to verify and refine our model and measured items, we may have a set of standard measured items for corporate sustainability, whether in a social enterprise setting or in a typical profit-seeking enterprise setting. Since Theptarin Hospital is a private family business, this study excludes the aspect of corporate governance where publicly disclosed information is required. Therefore, future corporate sustainability research into publicly listed companies should consider incorporating corporate governance aspects.

More specifically, the literature on corporate governance and corporate sustainability has pointed out that the design of an executive compensation and incentive scheme plays a critical role in ensuring corporate sustainability among publicly listed companies [

8]. Often, the executive compensation and incentive scheme, including stock options, is linked to firm profitability [

219]. The executive equity incentive could potentially affects practices of a company, shifting from prioritizing good governance to corporate value optimization [

219]. This is consistent with the industry tournament theory [

220] which purposes that executive industry tournament incentives have substantial power leading to firm performance [

221]. In this case, if the executive compensation and incentive scheme is not designed in such a way that the executives try to balance between maximizing short-term profitability and long-term corporate sustainability, it could potentially lead to corporate destruction [

8] as the executives will do everything ethically or unethically to maximize short-term profits for the shareholders. Clearly, future research should investigate the relationship between the executive compensation and incentive scheme and corporate sustainability prospect.

Additionally, it is believed that firm values can be enhanced by tying executive compensation to corporate social responsibility contracts, thus aligning the interests of executives with their shareholders [

222]. Providing executives with direct incentives for corporate social responsibility can essentially increase corporate social performance [

223]. Therefore, in trying to balance between maximizing short-term profitability and long-term corporate sustainability, the corporate social responsibility contract may be an approach to prevent powerful executives from adopting non-sustainable business practices [

224], pending future research. Another approach to prevent corporate disaster is called mutual monitoring, where the second-in-command has a fiduciary obligation to report critical, reliable and accurate information to the board, and monitors the top executive for his/her own sake [

225]. The mutual monitoring practice can theoretically lead to better executive decisions on investment and financial policy, causing a lower likelihood of illegal, unethical events or corporate bankruptcy. Clearly, future research should investigate into the relationships between the adoption of mutual monitoring practice and corporate sustainability prospect among publicly listed firms.

Specific to Sufficiency Economy philosophy research, future research may continue to refine our proposed theory of Sufficiency Economy in business to address the lack of theoretical foundation in the corporate sustainability field by building upon the theoretical ground we have provided in the present study.

8.2. Managerial Implications

This present study offers some important practical implications for corporate leaders. First, in terms of the Leadership practice, corporate leaders should select and retain employees with perseverance as a personal value so that in a tough time, they will persist despite obstacles. Moreover, they should involve employee creativity in the entire innovation process, while integrating social and environmental responsibility in its innovation. To ensure sustainable success, they should always adjust their standards to meet increasing customer expectations.

In addition, corporate leaders should be willing to sacrifice a short-term profit for a long-term, sustainable relationship with customers and other business partners. They should invest now for the future in a project that can reduce costs and benefit their companies in the long run. Their businesses should be expanded only when it can be expected that the expansion will bring about long-term yields. They should formulate a policy to increase sales volume in a regulated way rather than simply maximizing it. Using internal capital should be given priority, rather than loans from financial institutions for fast and radical expansion.

In terms of creating an alignment between corporate values and personal values such as perseverance, corporate leaders may consider adapting the Culture Development framework by Ketprapakorn and Kantabutra (2019) [

21] to develop a sustainability culture for their organization.

Although our finding indicates that the Resilience Development practice does not directly predict enhanced Socioeconomic Performance, it does so indirectly. Therefore, corporate leaders should start with continuously improving product and process technology by conducting a market analysis to guide innovation and market expansion. They should plan for the unexpected change and manage uncertainty and change, though requiring an investment. A good relationship with their suppliers and other stakeholders should be developed and maintained.

The Stakeholder Focus practice starts with demonstrating a keen sense of responsibilities and ethical conduct towards the best interests of stakeholders. Corporate leaders should financially support local traditions and cultural activities. They should also sponsor local events and school activities. Social and environmental responsibility should be integrated with their entire operations.

Lastly, corporate leaders should make Sharing a policy. Sharing knowledge should be done within their organizations and outside. This includes sharing non-competitive and collaborative know-how with competitors.