Opportunities for the Adoption of Health-Based Sustainable Dietary Patterns: A Review on Consumer Research of Meat Substitutes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

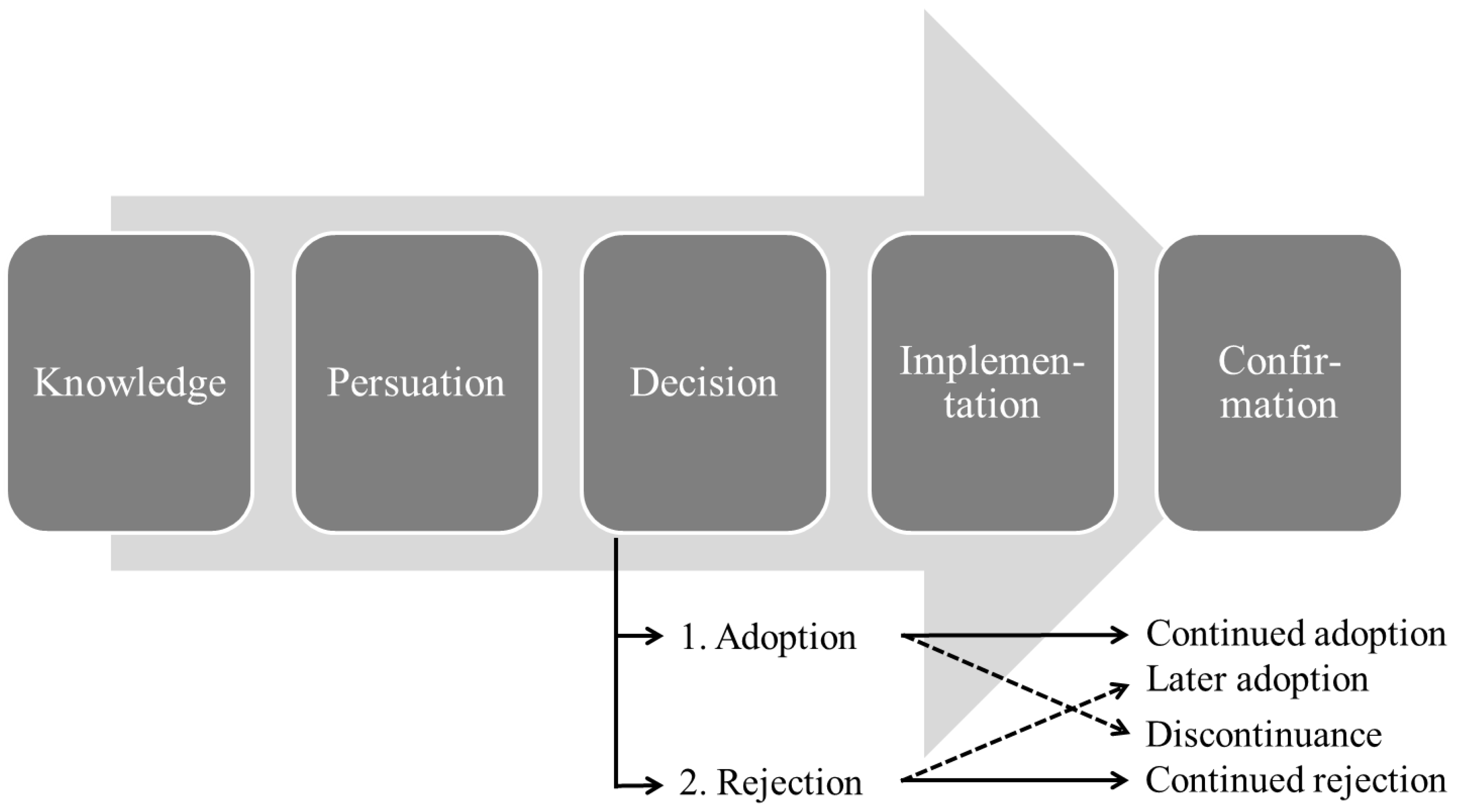

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Material and Methods

- A focus on life-cycle assessment that does not include consumer research

- A technical focus which does not include consumer research as well

- A focus on nutritional physiology which does not explain why consumer decide for or against a meat substitute

- Studies that were not in English language were excluded due to language barriers for a majority (French, German, Polish, Spanish, Turkish)

- Only studies with primary data were included, i.e. consumer studies. Studies based on secondary data or reviews were excluded.

4. Results

5. Discussion and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibson, R.B. Beyond the pillars: Sustainability assessment as a framework for effective integration of social, economic and ecological considerations in significant decision-making. J. Environ. Assess Policy Manag. 2006, 8, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunkeler, D.; Rebitzer, G. The future of life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2005, 10, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opp, S.M.; Saunders, K.L. Pillar talk: Local sustainability initiatives and policies in the United States—Finding evidence of the “Three E’s”. Economic Development, Environmental Protection, and Social Equity. Urban Aff. Rev. 2013, 49, 678–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, J.; Kyle, J.; Horgan, G.; Loe, J.; Fyfe, C.; Johnstone, A.; McNeill, G.; Livewell, G. A Balance of Healthy and Sustainable Food Choices; Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, World Wildlife Fund UK: Aberdeen, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oostindjer, M.; Alexander, J.; Amdam, G.V.; Egelandsdal, B. The role of red and processed meat in colorectal cancer development: A perspective. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 2657–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, Y.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E.; Liu, S. A Prospective Study of Red Meat Consumption and Type 2 Diabetes in Middle-Aged and Elderly Women. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2108–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, F.; Burley, V.; Greenwood, D.C.; Cade, J.E. Meat consumption and risk of breast cancer in the UK Women’s Cohort Study. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Available online: http://www.aicr.org/assets/docs/pdf/reports/Second_Expert_Report.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- Helms, M. Food sustainability, food security and the environment. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Chatli, M.K.; Mehta, N.; Singh, P.; Malav, O.P.; Verma, A.K. Meat analogues: Health promising sustainable meat substitutes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2015, 57, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2017, 57, 3640–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perignon, M.; Vieux, F.; Soler, L.G.; Masset, G.; Darmon, N. Improving diet sustainability through evolution of food choices: Review of epidemiological studies on the environmental impact of diets. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzerman, J.E.; Hoek, A.C.; van Bockel, M.A.J.S.; Luning, P.A. Consumer acceptance and appropriateness of meat substitutes in a meal context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoek, A.C.; van Bockel, M.A.J.S.; Voordouw, J.; Luning, P.A. Identification of new food alternatives: How do consumers categorize meat and meat substitutes? Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; Luning, P.A.; Weijzen, P.; Engels, W.; Kok, F.J.; de Graaf, C. Replacement of meat by meat substitutes. A survey on person- and product-related factors in consumer acceptance. Appetite 2011, 56, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeke, W. Profiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a Western society. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malav, O.P.; Talukder, S.; Gokulakrishnan, P.; Chand, S. Meat analog: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2011, 55, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, J.K.; McConnell, K.E. A Review of WTA/WTP Studies. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2002, 44, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Kling, C.L. Willingness to pay, compensating variation, and the cost of commitment. Econ. Inq. 2004, 42, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegmund, B. Lebensmittelsensorik als Essenzielles Werkzeug in der Qualitätssicherung und Produktentwicklung (Food Sensors as an Essential Tool in Quality Assurance and Product Development); University of Technology: Graz, Austria, 2010; Available online: http://foodscience.tugraz.at/ebook-proceedings/Siegmund-Vortrag.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2018).

- Barrena, R.; García, T.; Camarena, M. An Analysis of the Decision Structure for Food Innovation on the basis of consumer age. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, S.; Choo, H.J.; Pysarchik, D.T. Adopters of new food products in India. J. Mark. Pract. Appl. Mark. Sci. 2004, 22, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmerling, S.; Hamm, U.; Spiller, A. Consumption behaviour regarding organic food from a marketing perspective—A literature review. Org. Agric. 2015, 15, 227–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. How are organic food prices affecting consumer acceptance? A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Mutz, R. Growth rates of modern science: A bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Tech. 2015, 66, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schröck, R.; Herrmann, R. Fettarm und erfolgreich? Eine ökonometrische Analyse von Bestimmungsgründen des Erfolgs von Innovationen am deutschen Joghurtmarkt (Low-fat and successful? An econometric analysis of the reasons for the success of innovations on the German yoghurt market). Schriften der Gesellschaft für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften des Landbaues e.V. (Publications of the Society for Economic and Social Sciences of Agriculture e.V.) 2010, 45, 487–489. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke, W.; Sans, P.; van Loo, E.J. Challenges and prospects for consumer acceptance of cultured meat. J. Integr. Agr. 2015, 14, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, S.; de-Magistris, T. Information Bias Condemning Radical Food Innovators? The Case of Insect-Based Products in The Netherlands. Int. Food Agribus. Man. 2013, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barsics, F.; Caparros Megido, R.; Brostaux, Y.; Barsics, C.; Blecker, C.; Haubruge, E.; Francis, F. Could new information influence attitudes to foods supplemented with edible insects? Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2027–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarney, L.J. Communication Problems in the Marketing of Synthetic Meats. Eur. J. Mark. 1975, 9, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicatiello, C.; de Rosa, B.; Franco, S.; Lacetera, N. Consumer approach to insects as food: Barriers and potential for consumption in Italy. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2271–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Aiking, H. Towards a reduced meat diet: Mindset and motivation of young vegetarians, low, medium and high meat-eaters. Appetite 2017, 113, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohamed, Z.; Terano, R.; Yeoh, S.J.; Iliyasu, A. Opinions of non-vegetarian consumers among the Chinese community in Malaysia toward vegetarian food and diets. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, H. Ethical consumption, meaningful substitution and the challenges of vegetarianism advocacy. Geogr. J. 2014, 182, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, A.; Moon, W.; Balasubramanian, S.V. Soyfood Consumption Patterns: Effects of Product Attributes and Household Characteristics. J. Food Distr. Res. 2008, 39, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, A.C.; Luning, P.A.; Stafleu, A.; de Graaf, C. Food-related lifestyle and health attitudes of Dutch vegetarians, non-vegetarian consumers of meat substitutes, and meat consumers. Appetite 2004, 42, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schösler, H.; de Boer, J.; Boersema, J.J. Fostering more sustainable food choices: Can Self-Determination Theory help? Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 35, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, C.; McLeay, F. Should we stop meating like this? Reducing meat consumption through substitution. Food Policy 2016, 65, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Apostolidis, C.; McLeay, F. It’s not vegetarian, it’s meat-free! Meat eaters, meat reducers and vegetarians and the case of Quorn in the UK. Soc. Bus. 2016, 6, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G.; Fischer, A.R.H.; Tinchan, P.; Stieger, M.; Steenbekkers, L.P.A.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Insects as food: Exploring cultural exposure and individual experience as determinants of acceptance. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 42, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; van Loo, E.J.; Gellynck, X.; Verbeke, W. Flemish consumer attitudes towards more sustainable food choices. Appetite 2013, 62, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros Megido, R.; Gierts, C.; Blecker, C.; Brostaux, Y.; Haubruge, E.; Alabi, T.; Francis, F. Consumer acceptance of insect-based alternative meat products in Western countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Magistris, T.; Parcucci, S.; Mitsopoulos, D. Paying to see a bug on my food How regulations and information can hamper radical innovations in the European Union. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzerman, J.E.; van Bockel, M.A.J.S.; Luning, P.A. Exploring meat substitutes: Consumer experiences and contextual factors. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Sogari, G.; Veneziani, M.; Simoni, E.; Mora, C. Eating novel foods: An application of the Theory of Planned behaviour to predict the consumption of an insect-based product. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 59, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Aiking, H. ‘Meatless days’ or ‘less but better’? Exploring strategies to adapt Western meat consumption to health and sustainability challenges. Appetite 2014, 76, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzerman, J.E.; Hoek, A.C.; van Bockel, M.A.J.S.; Luning, P.A. Appropriateness, acceptance and sensory preferences based on visual information: A web-based survey on meat substitutes in a meal context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 42, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, M.J.C.; Ellis, S.M.; Bouwer, S.C.; Jerling, J.; Erasmus, A.C.; Harmse, N.; Badham, J. South African consumers’ opinions and consumption of soy and soy products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R. Cross-Cultural Comparison between German, French and Dutch Consumer Preferences for Meat Substitutes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; Elzerman, J.E.; Hageman, R.; Kok, F.J.; Luning, P.A.; de Graaf, C. Are meat substitutes liked better over time? A repeated in-home use test with meat substitutes or meat in meals. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Term | Number of Publication | Category | Number of Publications |

|---|---|---|---|

| “meat substitute*” AND consum* | N = 27 | Knowledge | 3 |

| Persuasion | 9 | ||

| Decision | 7 | ||

| Implementation | 8 | ||

| Confirmation | - |

| Author(s), Year of Publication | Country of Data Collection, Sample Size | Survey Design; Method | Type of Meat Substitute | Main Theory | Research Question | Main Conclusion | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apostolidis and McLeay, 2016a | UK, 247 consumers | Questionnaire; discrete choice experiment | Plant-based meat substitutes | Random Utility Theory | Which role can plant-based meat substitutes play in the policy agenda? | Latent class analysis identified six consumer segments: price conscious, healthy eaters, taste driven, green, organic and vegetarian consumers that should be addressed differently | Decision |

| Apostolidis and McLeay, 2016b | UK, 32 vegetarians, meat reducers and meat eaters | Group interview sessions; content analysis | Mycoprotein products | Means-end chain approach; Schwarz’s theory of basic values | How can values and benefits influence consumers’ preferences for meat substitutes? | Most consumers associated Mycoprotein products with health and sustainability-related benefits driven by values of security, benevolence and universalism | Persuasion |

| Barsics et al., 2017 | Belgium, 135 undergraduate students | Taste testing session; generalised linear model, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney ranked sum tests | Insect-based products | N/A | Would a broad-based information session affect consumers’ perceptions and attitudes about an edible insect product? | Information about insect-based products can changed consumers’ perceptions of insect products | Knowledge |

| Bosman et al., 2009 | South Africa, 2,437 consumers (Whites, Blacks, Coloureds and Indians) | Questionnaire; univariate and bivariate methods | Soy products | N/A | What are South African consumers’ attitudes to soy products? | More than 60% of the population within all race groups were positive about soy and found soy to be a good source of protein with health benefits and agreed that soy can replace meat | Implementation |

| Cicatiello et al., 2016 | Italy, 201 consumers | Questionnaire; logistic regression | Insects | N/A | What are Italian consumers’ attitudes to insects as food? | Familiarity with foreign food as well as higher education and male gender positively influenced to consume insects | Persuasion |

| De Boer et al., 2014 | The Netherlands, 1,083 consumers | Questionnaire; regressions | Generic | N/A | Which are change strategies that may help to reduce animal protein consumption and replace it by plant proteins? | Different strategies to change meat eating frequencies and meat portion sizes were described according to consumer segments and corresponding preferences | Implementation |

| De Boer et al., 2017 | The Netherlands, 707 (native Dutch, n = 357, second generation Chinese Dutch, n = 350) | Questionnaire; regressions | Generic | Self-Determination Theory | What is the motivation for different diets (young self-declared vegetarians, low, medium and high meat- eaters)? | Different from high meat eaters, for low and medium meat eaters health is the main reason to eat less meat and they liked to vary theirs meals | Persuasion |

| De Magistris et al., 2015 | The Netherlands, 153 consumers | Questionnaire; discrete choice experiment | Insect-based products | Random utility theory and Lancaster’s consumer theory | What is the role of the European Novel Food Regulation on consumers’ acceptance of and willingness to pay (WTP) for radical food innovations? | The visualization of insects on a product package might inhibit the success of insects as food | Confirmation |

| Elzerman et al., 2011 | The Netherlands, 93 consumers | Taste testing session; univariate and bivariate methods | Mycoproteinand soy | N/A | What is the influence of the meal context on the acceptance of meat substitutes? | During product development, more emphasis should be put on the meal context | Implementation |

| Elzerman et al., 2013 | The Netherlands, 46 consumers | Focus group discussions and taste session; descriptive analysis | Generic, tofu and mycoprotein | N/A | What are consumers’ experiences and sensory expectations of meat substitutes and the appropriateness of meat substitutes in meals? | Negative sensory aspects of meat substitutes were uniform taste, compactness, dryness and softness; most consumers found the use of meat substitutes appropriate in the dishes shown | Implementation |

| Elzerman et al., 2015 | The Netherlands, 251 consumers | Questionnaire; univariate and bivariate methods | Generic | N/A | How do consumers rate appropriateness of meat substitutes in different dishes given visual information? | Appropriateness of meat substitutes in a dish is related to attractiveness and use-intention, thus meal context should be taken into consideration when developing new meat substitutes | Implementation |

| Hoek et al, 2004 | The Netherlands, 4415 consumers (Vegetarians, n = 63, and consumers of meat substitutes, n = 39, meat eaters, n = 4313) | Questionnaire; logistic regression | Generic | N/A | How can meat eaters, vegetarians and meat substitute consumers be distinguished regarding socio-demographic characteristics, attitudes to food and health? | Strategies to promote meat substitutes for meat eaters should not only focus on health and ecological aspects of foods | Persuasion |

| Hoek et al, 2011a | UK and the Netherlands, 553 (non-users n = 324, light/medium-users n = 133, heavy-users of meat substitutes n = 96) | Questionnaire; regression | Generic | Usage segmentation, Stages of Change model | What is necessary to increase the consumption of meat substitutes? | The focus should not be on communication of ethical arguments, but the sensory quality and resemblance to meat of the meat substitute should be improved | Confirmation |

| Hoek et al, 2011b | The Netherlands, 34 consumers | Questionnaire; multi-dimensional scaling | Soy, vegetable, wheat, lentiles, pea, fungi | N/A | Which product category representations of meat substitutes have consumers in mind? | Innovative meat substitutes should have a resemblance to meat in order to replace meat | Implementation |

| Hoek et al, 2013 | The Netherlands, 89 consumers | Questionnaire; regression | Tofu, mycoprotein | N/A | What can the long-term consumer acceptance of meat substitutes influence positively? | Liking of a meat substitute can be increased by repeated exposure for a segment of consumers | Implementation |

| McCarney, 1975 | N/A | Qualitative interviews, | Synthetic meat | Theory of opinion leaders | How can synthetic meat be marketed? | Impediments to try meat substitutes were unfamiliarity, physical appearance, taste, nutritional value, availability of other substitutes like fish and the artificiality of the product | Persuasion |

| Megido et al., 2016 | Belgium, 79 students | Questionnaire and tasting session; univariate and bivariate methods | Insect- and lentil-based products | N/A | What is the level of sensory liking for hybrid insect-based burgers? | Insect tasting sessions can help to decrease food neophobia | Confirmation |

| Menozzi et al, 2017 | Italy, 231 consumers | Questionnaire; Structural Equation Modelling | Insect-based products | Theory of Planned Behaviour | What is consumers’ intention to and the behaviour of eating products containing insect flour in the next month? | Main barriers to consuming insect products are the sense of disgust, the incompatibility with local food culture and a lack of availability in the supermarket | Implementation |

| Mohamed et al., 2016 | Malaysia, 500 consumers (among the Chinese community) | Questionnaire; factor analysis and binary logistics | Vegetarian food products | N/A | What are the dimensions of non-vegetarian consumers’ opinions toward vegetarian food? | Influencing factors are environmental and animal well-being concerns, being taught to be vegetarian for religious reasons, and the influence of surrounding people on eating habits | Persuasion |

| Neo, 2014 | Taiwan, 14 consumers | In-depth interviews; descriptive analysis | Generic | N/A | What are the challenges for an ethical consumption characterized by less meat consumption? | The various moral and nature-based framings of vegetarianism is weakened by the availability of a meat substitute | Persuasion |

| Pascucci and de-Magistris, 2013 | The Netherlands, 122 consumers | Questionnaire; choice experiment | Insect-based products | Random utility theory and Lancaster’s consumer theory | Is information affecting consumers’ WTP for insect-based products? | While visualization negatively influenced consumers’ WTP, information treatments do not mitigate this effect | Knowledge |

| Rimal et al., 2009 | US and Canada, 3,000 households | Questionnaire; binary-choice model and a zero-inflated negative binomial model | tofu, vegetable burgers, soy milk, soy supplements, meat substitutes, and soy cheese | Lancaster’s characteristics model and Fishbein’s multi-attribute model | What are soy food consumption patterns? | Convenience of preparation and consumption and taste had strong effects on the consumption of soy products | Persuasion |

| Schösler et al., 2014 | Netherlands, 1,083 consumers | Questionnaire, factor and cluster analysis | Generic | Self-Determination Theory | Can Self-Determination Theory help to foster more sustainable food choices? | Self-Determination Theory provided theoretical as well as policy-oriented insights into promoting more sustainable food choices | Persuasion |

| Tan et al., 2015 | The Netherlands and Thailand, 54 consumers | Focus group interviews; coding | Insects and insect-based products | N/A | How does cultural exposure and individual experience contribute towards the evaluations of insects as food by consumers who have eaten and who have not eaten it yet? | Factors were identified that need to be taken into consideration when introducing insects to a culture where this food is not yet accepted | Confirmation |

| Van Honacker, 2013 | Belgium, 221 participants | Questionnaire; factor and cluster analysis | Sustainable farmed fish, hybrid meat types, plant-based meat substitutes, insects | N/A | What are consumer opinions toward food choices with a lower ecological impact? | Consumers were rather reluctant to alternatives that (partly) ban or replace meat in the meal; opportunities of introducing insects (currently) appeared to be non-existent | Confirmation |

| Verbeke et al., 2015 | Belgium, 180 participants | Questionnaire; univariate statistics | Cultured meat | N/A | Is cultured meat accepted by consumers? | A minority of consumers rejected the idea of cultured meat | Knowledge |

| Verbeke, 2015 | Belgium, 368 participants | Questionnaire; binary logistic regression | Insects | N/A | Which consumer types are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute? | The relevant consumers were characterised to be male, having a weak attachment to meat, were more open to trying novel foods and were interested in the environmental impact of their food choice | Confirmation |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weinrich, R. Opportunities for the Adoption of Health-Based Sustainable Dietary Patterns: A Review on Consumer Research of Meat Substitutes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154028

Weinrich R. Opportunities for the Adoption of Health-Based Sustainable Dietary Patterns: A Review on Consumer Research of Meat Substitutes. Sustainability. 2019; 11(15):4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154028

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeinrich, Ramona. 2019. "Opportunities for the Adoption of Health-Based Sustainable Dietary Patterns: A Review on Consumer Research of Meat Substitutes" Sustainability 11, no. 15: 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154028

APA StyleWeinrich, R. (2019). Opportunities for the Adoption of Health-Based Sustainable Dietary Patterns: A Review on Consumer Research of Meat Substitutes. Sustainability, 11(15), 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154028