Conceptualising Tourism Sustainability and Operationalising Its Assessment: Evidence from a Mediterranean Community of Projects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Do specific objectives affect perceptions of actors and stakeholders towards the concept of tourism sustainability?

- Do different perceptions of sustainability affect the perceived Ease of Use and Usefulness towards TSA Initiatives?

- What are the main gaps and challenges regarding the operationalization of Tourism Sustainability Assessments?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Conceptualising Tourism Sustainability within the Projects Community

3.2. Evaluating Perceived ‘Usefulness’ and ‘Ease of Use‘ of TSA Initiatives

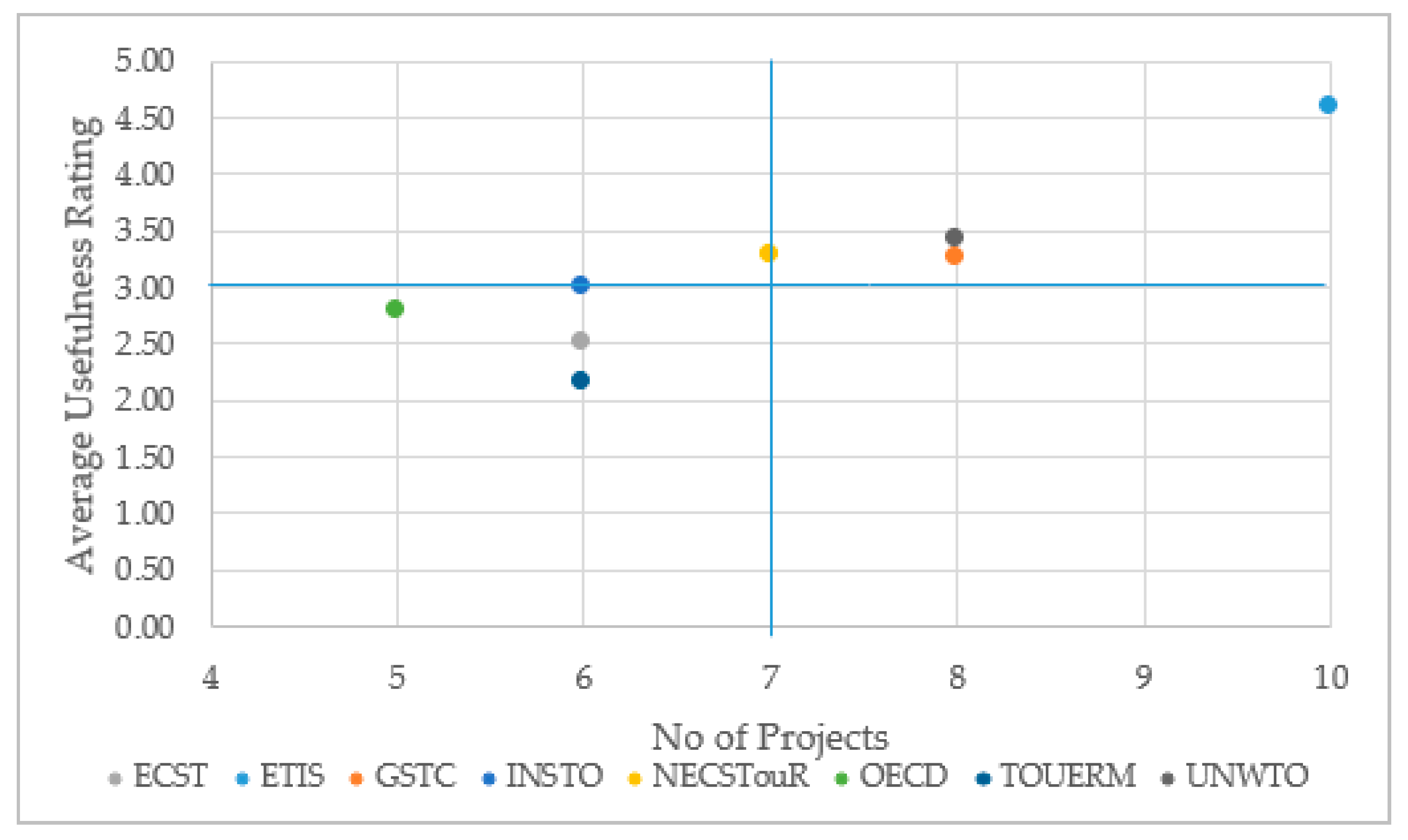

3.2.1. Perceived ‘Usefulness’

3.2.2. Perceived ‘Ease of Use’

3.3. Evaluating Gaps and Challenges of Tourism Sustainability Assessment (TSA) Implementation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2017 Edition. 2017. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419029 (accessed on 11 January 2018).

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Richards, G.; Hall, D. Tourism and Sustainable Community Development; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coccossis, H.; Mexa, A. The Challenge of Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment: Theory and Practice; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management; Cabi Publishing: Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jovicic, D.Z. Key issues in the implementation of sustainable tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.; Lee, B.; Shafer, C.S. Operationalizing sustainability in regional tourism planning: An application of the limits of acceptable change framework. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Palomeque, F.L. Measuring sustainable tourism at the municipal level. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; González, M.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; Perez, F. The assessment of sustainable tourism: Application to Spanish coastal destinations. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Saarinen, J. Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Measuring Sustainable Tourism Brochure. 2018. Available online: http://cf.cdn.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/folderfactsheetweb.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2018).

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC). GSTC Strategic Plan 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.gstcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/GSTC-Strategic-Plan-2017-web.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2018).

- European Charter for Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas (ECST). The Charter. 2010. Available online: https://www.europarc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2010-European-Charter-for-Sustainable-Tourism-in-Protected-Areas.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- European Commission. The European Tourism Indicator System: ETIS toolkit for sustainable destination management. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/21749/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 18 January 2018).

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Measuring Sustainable Tourism: Developing a statistical framework for sustainable tourism, Overview of the initiative. 2016. Available online: http://cf.cdn.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/mstoverviewrev1.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2018).

- United Nations. Tourism Satellite Account: Recommended Methodological Framework 2008. 2010. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/tradeserv/tourism/manual.html (accessed on 17 January 2018).

- United Nations. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/83/Rev.1. 2008. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/Seriesm/SeriesM_83rev1e.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Giulietti, S.; Romagosa, F.; Fons, J.; Schröder, C. Developing a “Tourism and Environment Reporting Mechanism” (TOUERM): Environmental impacts and sustainability trends of tourism in Europe. In Proceedings of the 14th Global Forum on Tourism Statistics, Venice, Italy, 23–25 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dupeyras, A.; MacCallum, N. Indicators for Measuring Competitiveness in Tourism: A Guidance Document. OECD Tourism Papers 2013. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/5k47t9q2t923-en (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Núñez, C. NECSTouR: How to Encourage Partnerships and Cooperation in Regions. 2015. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/8536/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission—Agenda for a Sustainable and Competitive European Tourism COM/2007/0621 Final. 2007. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52007DC0621&from=EN (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Rules for the Operation and Management of the UNWTO International Network of Sustainable Tourism Observatories (INSTO). 2018. Available online: http://insto.unwto.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/INSTO_Framework_EC2016.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2018).

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M.; Vinzón, L. Sustainability indicators of rural tourism from the perspective of the residents. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, P.; Capocchi, A.; Foroni, I.; Zenga, M. An Assessment of the Implementation of the European Tourism Indicator System for Sustainable Destinations in Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B. Sustainability Assessment: Exploring the Frontiers and Paradigms of Indicator Approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; McKercher, B.; Suntikul, W. Identifying core indicators of sustainable tourism: A path forward? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Presentations from the ETIS and Accessible Tourism Conference. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/15362/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Pilot Studies and Country Experiences. Available online: http://statistics.unwto.org/studies_experiences (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Kozic, I.; Corak, S.; Marusic, Z.; Markovic, I.; Sever, I. Preliminary Report of Croatian Sustainable Tourism Observatory. Focal Area: Adriatic Croatia; Institute for Tourism: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Markovic Vukadin, I.; Marusic, Z.; Kozic, I.; Telisman Kosuta, N. Croatian Sustainable Tourism Observatory 2018 Report Focal Area: Adriatic Croatia; Institute for Tourism: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dangi, T.B.; Jamal, T. An Integrated Approach to “Sustainable Community-Based Tourism”. Sustainability 2016, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutana, S.; Mukwada, G. An Exploratory Assessment of Significant Tourism Sustainability Indicators for a Montane-Based Route in the Drakensberg Mountains. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudorache, D.M.; Simon, T.; Frenț, C.; Musteaţă-Pavel, M. Difficulties and Challenges in Applying the European Tourism Indicators System (ETIS) for Sustainable Tourist Destinations: The Case of Braşov County in the Romanian Carpathians. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. The psychological origins of perceived usefulness and ease-of-use. Inf. Manag. 1999, 35, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, A.L.; Maupin, D.J.; Sena, M.P.; Zhuang, Y. The technology acceptance model and the World Wide Web. Decis. Support Syst. 2000, 29, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.E.; Donthu, N. Using the technology acceptance model to explain how attitudes determine Internet usage: The role of perceived access barriers and demographics. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fang, S.; Jin, P. Modeling and Quantifying User Acceptance of Personalized Business Modes Based on TAM, Trust and Attitude. Sustainability 2018, 10, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Tourism, heritage and cultural sustainability: Three ‘golden rules’. In Cultural TOUrism and Sustainable Local Development; Girard, L.F., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Surrey, UK; Burrlington, VT, USA, 2009; pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R.; Glozer, S.; Crane, A.; McCabe, S. Tourists’ accounts of responsible tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TSAI | Target Groups | Criteria | Spatial Scale | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Sustainable Tourism Council—GSTC [13] | Two sets of Indicators Targeting at Policy Makers and Private Actors | (1) Sustainable management | Local | Indicators |

| (2) Socioeconomic impacts | ||||

| (3) Cultural impacts | ||||

| (4) Environmental impacts | ||||

| United Nations World Tourism Organisation—UNWTO [16] | Policy Makers | The most recent revision includes only indicators for Economy and Employment | National | Data and Indicators |

| Tourism Satellite Account—TSA [17] | Policy Makers | (1) Visitors consumption | National | Data and Indicators |

| (2) Production of goods and services | ||||

| (3) International trade of goods and services | ||||

| (4) Number of jobs | ||||

| International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics—IRTS [18] | Policy Makers | (1) Measuring Flows of Visitors | National | Indicators |

| (2) Measuring the characteristics of visitors and tourism trips | ||||

| (3) Measuring Tourism Expenditure | ||||

| (4) Measuring the supply of services of tourism industries | ||||

| (5) Measuring Employment | ||||

| International Network of Sustainable Tourism Observatories (INSTO) [23] | Policy Makers | Various Criteria According to the Observatory | National/Local | Data |

| Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development—OECD [20] | Policy Makers | (1) Tourism performance and Impacts | National | Indicators |

| (2) Ability of a destination to deliver quality and competitive tourism services | ||||

| (3) Attractiveness of a destination | ||||

| (4) Policy responses and economic opportunities | ||||

| European Tourism Indicators System—ETIS [15] | Policy Makers | (1) Destination management | Local | Indicators |

| (2) Social and Cultural Impact | ||||

| (3) Environmental Impact | ||||

| Tourism and Environment Reporting Mechanism—TOUERM [19] | Policy Makers | (1) Driver indicators | Various | Data/Indicators |

| (2) Pressure indicators | ||||

| (3) State indicators | ||||

| (4) Impact indicators | ||||

| (5) Response indicators | ||||

| Network of European Regions for Sustainable and Competitive Tourism—NECSTouR [21] | Policy makers | (1) Limit the environmental impact of transport | Local | Indicators |

| (2) Increase the quality of life of residents | ||||

| (3) Increase the quality of employment | ||||

| (4) Reduce the seasonality of tourism flows | ||||

| (5) Protect the cultural heritage | ||||

| (6) Protect the environmental heritage | ||||

| (7) Protect the identity of destinations | ||||

| (8) Reduce and optimise the use of natural resources and water in particular | ||||

| (9) Reduce and optimise energy consumption | ||||

| (10) Reduce and manage waste | ||||

| European Charter for Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas—ECST [14] | Managers of Protected Areas | (1) Partnership with local tourism stakeholders | Local | Indicators |

| (2) Sustainable tourism strategy and action plan | ||||

| (3) Protecting natural and cultural heritage | ||||

| (4) Meeting visitor needs/quality of experience | ||||

| (5) Communication about the area | ||||

| (6) Tourism products relating to the protected area | ||||

| (7) Training | ||||

| (8) Community involvement and maintaining local quality of life | ||||

| (9) Benefits to the local economy and local community | ||||

| (10) Managing visitor flows |

| Project | Scope | Perception of Tourism Sustainability | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management and Monitoring | Preserving Local Identity | New Tourism Models | Development of Circular and Green Economy | Awareness and Responsibility | Resources Protection | Social Dialogue | Innovation | Opportunities | Total | ||

| ALTER ECO | Developing alternative tourist strategies in order to enhance the local sustainable development of tourism by promoting Med identity | x | x | x | 3 | ||||||

| BLUEISLANDS | Improving waste management and monitoring in Med islands | x | x | x | 3 | ||||||

| BLUEMED | Plan/test/coordinate Underwater Museums, Diving Parks and Knowledge Awareness Centres | x | x | x | x | 4 | |||||

| CASTWATER | Improving water management at Med coastal areas | x | x | x | x | x | 5 | ||||

| CO-EVOLVE | Promoting the co-evolution of human activities and natural systems for the development of sustainable coastal and maritime tourism | x | 1 | ||||||||

| CONSUME-LESS | Building and promoting a sustainable tourism model based on the “consume-less” notion | x | x | 2 | |||||||

| DestiMED | Paving the way for the development of a Destination Management Organization for ecotourism in protected areas | x | x | x | 3 | ||||||

| EMbleMatiC | Creating and testing a new and radically different tourism offer based on the features of Emblematic Med mountains | x | x | x | 3 | ||||||

| MEDCYCLETOUR | Valorising EuroVelo 8 cycle tour towards more sustainable Med tourism | x | x | 2 | |||||||

| MEDFEST | Promoting culinary tourism based on Med heritage and diet | x | x | x | 3 | ||||||

| MITOMED+ | Improving local and regional strategies and policy actions by to increasing knowledge and social dialogue | x | x | x | 3 | ||||||

| ShapeTourism | Improving Decision-Making in Tourism by enhancing the tourism knowledge framework | x | x | x | x | x | 5 | ||||

| SIROCCO | Developing new sustainable cruise tourism models in Med regions | x | x | 2 | |||||||

| TOURISMED | Creating and testing new fishing tourism business model | x | x | x | x | 4 | |||||

| Total | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Type of TSA | Project | TSAI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Rank | 2nd Rank | ||

| Destination | CO-EVOLVE | ETIS | GSTC |

| MITOMED+ | ETIS | NECSTouR | |

| ShapeTourism | ETIS | INSTO, UNWTO | |

| Destination and Product | MEDFEST | ETIS | GSTC |

| Product | DestiMED | ETIS | GSTC |

| Model | BLUEMED | ETIS | OECD, ECST |

| TOURISMED | ETIS | All (except for ECST) | |

| ALTER ECO | ETIS | TOUERM, NECSTouR | |

| Actors | SIROCCO | ETIS | GSTC |

| CASTWATER | ETIS | UNWTO | |

| TSAI | Applicability | Guidance | Flexibility | Sensitivity to Data | Stakeholders Engagement | Average Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECST | 5 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 4.4 |

| ETIS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 3.8 |

| GSTC | 8 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3.8 |

| INSTO | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4.6 |

| NECSTouR | 2 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 |

| OECD | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 4.6 |

| TOUERM | 6 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5.2 |

| UNWTO | 4 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 4.2 |

Highest rank

Highest rank  Lowest rank. Source: Authors’ own compilation of projects’ responses.

Lowest rank. Source: Authors’ own compilation of projects’ responses.| TSA Focus | Applicability | Guidance | Flexibility | Sensitivity to Data | Stakeholders Engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination | NECSTouR | UNWTO | UNWTO | Multiple | OECD |

| Product | ETIS | ETIS | GSTC ETIS | GSTC | GSTC ECST |

| Model | UNWTO ETIS NESCTOUR | UNWTO | ETIS | NECSTouR | GSTC NECSTouR |

| Actors | ETIS | GSTC INSTO ETIS | ETIS | GSTC ECST | ETIS |

| Scale | Applicability | Guidance | Flexibility | Sensitivity to Data | Stakeholders Engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | ETIS NECStouR | ETIS | TOUERM | OECD ECST | OECD TOUERM ECST |

| NUTS III | ETIS | ETIS | Multiple | OECD ECST | ECST |

| NUTS II | INSTO | ETIS | ETIS | ECST | UNWTO OECD ECST |

| Inter-Regional | GSTC ETIS | ETIS | GSTC ETIS | GSTC ETIS | GSTC ETIS |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niavis, S.; Papatheochari, T.; Psycharis, Y.; Rodriguez, J.; Font, X.; Martinez Codina, A. Conceptualising Tourism Sustainability and Operationalising Its Assessment: Evidence from a Mediterranean Community of Projects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154042

Niavis S, Papatheochari T, Psycharis Y, Rodriguez J, Font X, Martinez Codina A. Conceptualising Tourism Sustainability and Operationalising Its Assessment: Evidence from a Mediterranean Community of Projects. Sustainability. 2019; 11(15):4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154042

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiavis, Spyros, Theodora Papatheochari, Yannis Psycharis, Josep Rodriguez, Xavier Font, and Anna Martinez Codina. 2019. "Conceptualising Tourism Sustainability and Operationalising Its Assessment: Evidence from a Mediterranean Community of Projects" Sustainability 11, no. 15: 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154042