Abstract

This paper studies the dynamic relationship between consumption and investment in the United States between 1947 and 2018. Our findings support the postulates of Keynesian economics—while they are contrary to the theoretic background on which the numerous empirical studies on the saving-investment nexus are based. We find a long-run nexus between consumption and investment, and positive linear Granger-causality running unidirectionally from consumption to investment. Therefore, investment is sustained by consumption. Further, we find that the variables have nonlinear structures and, thus, we apply nonlinear causality tests. We provide evidence of nonlinear causality running unidirectionally from consumption to investment. Nevertheless, after controlling for Government Expenditure, this nonlinear causal relationship disappears, indicating that Government Expenditure drives the nonlinear causal relationship between private consumption and investment. We argue that this finding is consistent with the notion that investment decisions are guided by permanent aggregate demand, because public expenditure allows private consumption to have a sufficiently permanent trajectory to be considered as a guide for investment decisions. Our results do not support the austerity and deflation measures implemented in the last years (especially in the European Union). On the other hand, our findings call for the incentive of final public expenditure, since it favours the long-run link between the private decisions to consume and invest.

1. Introduction: Underinvestment and Underconsumption in the General Theory

In the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936) (hereafter, the GT), John Maynard Keynes emphasized that unemployment arises when investment is insufficient to cover the difference between production at full capacity and aggregate consumption when occupation is in that situation [1] (p. 27). Therefore, underinvestment is the main cause of unemployment in the GT. Underinvestment takes place when entrepreneurs’ future profits expectations are below the interest rate [1] (p. 370). And entrepreneurs’ future profits expectations depend mainly on the current demand for ordinary consumption [1] (p. 106). Thus, in the GT, the demand for capital depends mainly on the demand for consumption [1] (p. 106).

The GT develops a clear connection between the income multiplier and the accelerator of investment. The accelerator or acceleration principle is a theory of investment that incorporates the principle of effective demand into the dynamic analysis [2]. This theory of investment, developed even before the publication of the GT, is based solely on effective demand. The accelerator principle implies that investment depends exclusively on expected changes in income. Dynamic Keynesian macroeconomics has its root in the attempt of combining the multiplier and the accelerator. This was carried out by [3] in his famous article of 1939, and soon followed by [4]. The models that combine the multiplier with the accelerator are known as multiplier-accelerator models or, following the words of [5], Supermultiplier models. We document, however, that even before [3], Keynes had in mind that the income multiplier had to be accompanied by the investment accelerator.

If we look at the simple (without considering public and external sectors) Keynesian aggregate demand identity (), where is output, is the propensity to consume of the community, is the incremental capital-output ratio (the amount of capital required to increase each unit of total output), and is the derivative of with respect to time, we have that the sustainable rate of growth (the growth rate that allows the forces of supply and demand to evolve pari passu over time) is . This is, in fact, a version of the warranted rate of growth of [3]. Since is unknown, must be considered as the firms’ expectations of the growth rate of aggregate consumption. Entrepreneurs’ expectations about the evolution of consumption must be exogenous, or, at least, cannot be mechanically linked to the evolution of effective output, otherwise Harrodian dynamic instability appears (for recent states of the art on Harrodian instability, see [6,7,8,9]). (Dejuán 2005, 2017) [10,11], following [12], emphasize that the expected rate of growth of permanent aggregate demand is the variable that guides investment and, therefore, is the key variable in a multiplier-accelerator system.

So far, we have stated that, according to the GT, unemployment is caused when the actual propensity to consume infers an incentive to invest such that the resulting investment is not enough to cover the difference between production at full capacity and aggregate consumption when occupation is in that situation [1] (p. 27). According to Keynes, a socially inadequate income distribution causes consumption, and therefore investment, to be below the level that permits reaching full employment [1] (p. 373).

Keynes states that the remedy for an insufficient level of investment lies in various measures designed to increase the propensity to consume by the redistribution of incomes [1] (p. 324). Therefore, according to Keynes, the task of the State aimed at reaching full employment consists in adjusting the propensity to consume with the incentive to invest [1] (p. 379).

The GT endorses public intervention aimed at redistributing income to socially adjust consumption and investment, and thus to achieve full employment. The State can modify secondary income distribution via final public expenditure. In sum, public expending helps socially adjust private consumption and investment, thus making the relationship between both variables relatively sustainable over time.

In the following sections, we test the empirical validity of Keynes’s postulates about the relationship between consumption and investment. Our aim is to test whether there exists a positive causal relationship running unidirectionally from consumption to investment. Therefore, we test the empirical validity of the notion of investment in the multiplier-accelerator model presented by [4], which is a version of the model developed by [3].

According to mainstream economics, sustained on the marginalist theoretical corpus of the nineteenth century systematized and deepened by [13], capital consists of a fund of consumption goods through which consumption can be postponed (see [14], pp. 36–7). The existence of a decreasing demand schedule for capital that is elastic to the interest rate assures that a rise in ‘foresight’ saving is matched by additional capital accumulation that will lead, given the labor supply, to a higher per-capita capital endowment [15] (p. 223).

According to this approach, investment can fall below full-capacity saving only in the troughs of the economic cycle, where the shortfall of investment can be explained as ‘frictions’ due either to the functioning of the monetary system, which prevents interest rates from quickly adjusting to the return on capital or to periodic crises in entrepreneurs’ ‘psychological state of confidence’ that make investment spending inelastic with respect to interest rates, or to both circumstances operating together [16] (p. 112).

This notion of investment has led many economists to test the saving-investment nexus. Reference(Feldstein and Horioka, 1980) [17] empirically examined the relationship between savings and investment. Their results were mixed and contradictory, giving rise to the well-known Feldstein–Horioka puzzle. Since then, many authors have empirically tested whether savings and investment are cointegrated. References [18,19,20,21,22,23] are probably the most influential of a long list of empirical papers that try to solve the Feldstein–Horioka dilemma. For the moment, there is no consensus in the existing empirical literature regarding the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle [24] (p. 167).

This conventional savings-investment approach states that increased saving leads to higher economic growth through higher capital formation [25] (p. 2167). According to this approach, a weak domestic saving–investment correlation must be explained by a high international capital mobility. However, the neoclassical saving–investment nexus that states that domestic saving in northern countries finds an automatic debouche in investment in southern countries is not robust to the capital critiques of the 1950s and the 1960s (see [26] for a recent state of the art of the capital controversies). In light of this criticism, there is no automatic mechanism that translates the larger (potential) saving supply into domestic or foreign investment, since a fall in the interest rate does not affect investment either in the domestic economy or in that of other countries.

Our approach is different to the conventional approach exposed above. As stated, Keynes tried to explain that, within the limits of full productive capacity utilization, a larger amount of investment does not require a prior reduction in consumption, and that the higher level of output and income generated by the greater degree of capacity utilization generates savings equal to the decisions to invest [15]. Our paper contributes to the literature in two ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper that applies the nonlinear causality test of [27] to estimate Keynesian models. Second, even though our paper is closely related to the extensive literature inspired by the [28] model, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper that analyzes a cointegrating relationship between domestic consumption and domestic investment.

We use quarterly data from the United States (U.S.) between 1947 and 2018. We control for the wage mass, considering that changes in its tendency can affect both consumption and investment decisions. Even though we control for the wage mass, we do not focus on the effects that income (re)distribution has on consumption and on investment, as the models inspired by [28] do (for recent developments of these models, see [29,30,31,32,33]).

We first analyze whether there is a long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables. Then, we test for linear and non-linear causal relationships between consumption and investment. The variables under study are influenced simultaneously by the evolution of output, but if there is cointegration between these variables, then they share a common long-run trend, and the causality relationships between them are statistically valid, regardless of other variables influencing them. Therefore, a cointegration analysis is crucial for our investigation.

2. Econometrics Methodology

We apply the following methodology. First, we test if the variables are stationary or not through different unit root tests. Then, we test whether there exists cointegration among them. Finally, we apply linear and non-linear causality tests using the recently developed method by [27] (hereafter DW test).

2.1. Data

We employ U.S. quarterly data between 1947:Q1 and 2017:Q4. We use aggregate real consumption , aggregate real gross private investment , and the real wage mass, . We use Real Gross Private Domestic Investment as a proxy variable for , Real Personal Consumption Expenditures as a proxy variable for , and Compensation of Employees: Wages and Salary Accruals as a proxy variable for . All variables are measured in billions of chained 2009 dollars, seasonally adjusted. All the variables are transformed into natural logarithms. The data are obtained from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/).

2.2. Unit Root Tests and Cointegration Analysis

We first check for the stationarity of the variables. We apply the Augmented Dickey–Fuller [34] and the Phillips–Perron [35] unit root tests to check for the stationarity of the series. These methods are widely known and used in the literature, therefore, for reasons of space, we will not describe their methodology.

After checking the stationarity of the variables, we analyze whether the variables follow a long-run equilibrium relationship, i.e., are cointegrated. We apply the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) bounds test by [36]. This method does not require that all the variables have the same order of integration (number of times that they have to be differentiated to become stationary series), and it is valid for small sample sizes. The ARDL bounds test generates both long-run and short-run error correction simultaneously. The ARDL model that we propose to test for cointegration is the following:

where denotes first differences, and p is the selected lag order. , , and are investment, consumption, and the wage mass at time , respectively. T is a deterministic time trend, and is a white noise error term. The optimal lag order specification, , is selected by minimizing the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The lag length is validated by the absence of serial correlation in the residuals. The null hypothesis of no cointegration is:

against the alternative hypothesis of cointegration that:

Narayan (2005) [37] Derived critical values for testing above for sample sizes between 30 and 80 observations. If the F-statistic critical value is above the critical value of the significance level, then we reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration. As a robustness check for cointegration, we apply the cointegration test of [38]. We present the results of this test in the Appendix A.

Finding cointegration is important for our purposes, because the existence of cointegration between the variables under study indicates that no relevant integrated variables are omitted in the cointegrating regression. Since cointegration tests are robust to endogeneity, if a cointegrating relationship exists among a set of nonstationary variables, the same cointegrating relationship also exists in an extended variable space [39]. There are many variables that influence investment apart from consumption and the wage mass. Since the cointegration property is invariant to extensions of the information set, the estimates will not be significantly affected by the presence of additional variables [40].

2.3. Linear Granger-Causality Tests

After examining the existence of cointegration, the direction of the causality relationship between the variables needs to be identified [24] (p. 8), [41]. The hypothesis that we test sustain that movements of consumption help determine (predict) positive variations of investment. Following [42,43], there is Granger-causality from to if:

where and are the past information sets up to time of and , respectively, and is the conditional distribution function of conditioned on . then, if (2) is satisfied, we have that:

where is the mean of . Hence, we carry out a Granger-causality-in-mean test of (3) by applying a F-test on = 0, for all j, in a Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model.

The [44] approach to linear causality is considered an upgraded version of the Wald test. The method obtains efficient and consistent estimates even when the variables have different orders of integration. The model is constructed trough a Vector Autoregressive Regression (VAR) in levels:

where is the lag order that minimizes the AIC and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and is the maximum order of integration that all variables need to become stationary. The lag length is validated by the absence of serial correlation in the residuals. To test for Granger-causality, the method of [44] follows a Modified Wald (MWALD) test, ensuring that the test statistic has asymptotic chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom.

As a robustness check for Granger-causality, we also test for linear Granger-causality through a Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) estimated within the ARDL framework. We also implement a VECM through the traditional two-step (residual-based) approach of (Engle and Granger, 1987) [45]. A VECM is recommended for multivariate time series modeling in which the variables are cointegrated [46]. If the variables are stationary in first differences (are I (1) processes), we can consider a dynamic error correction model as follows:

where denotes the one-period lagged residual of the long-term cointegrating equation, and is the optimal lag length. The lag length is validated by the absence of serial correlation in the residuals.

The sources of Granger-causality are identified by testing the statistical significance of the coefficients of the independent variables in Equations (6) and (7). For example, to test whether consumption short-run Granger-causes investment, we test whether in Equation (6) for all . We analyze whether there is weak exogeneity by testing the significance of the adjustment speed, which is the coefficient of the error correction term, . We test the null hypothesis in Equation (6) and in Equation (7). For example, if is negative and statistically significant, then there is evidence that consumption and the wage mass jointly Granger-cause investment in the long run.

2.4. Nonlinear Causality Tests

Analyzing only linear dependencies implies leaving aside properties of the variables that are important when the series contain considerable nonlinearities. These nonlinearities arise in both the dynamics of an individual variable and in the relationships between variables [47] (p. 329). The limitation of the linear causality analysis is that it does not identify nonlinear causal relationships between variables [48].

We first analyze the presence of nonlinear structures in the variables through the linerality test of [49] (hereafter, BDS test). This test allows detecting deviations from independence in time series, such as linear, nonlinear dependence or chaos. The null hypothesis is that the residuals of the series are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.). Thus, rejecting the null hypothesis means that the variable contains nonlinearities. The BDS test is also well known and employed by the literature, so, for reasons of space, we will not develop its methodology.

Our final step is to check for the presence of nonlinear causal relationships between the variables. For this purpose, we employ the test of [27], which is a nonparametric test. The no parametrization implies testing non-Granger-causality against an unspecified alternative. This method avoids the problems of misspecification of the VAR model, and it detects linear and nonlinear Granger-causality. The drawback of the method of [27] is, however, the lack of information about the type of causality. This inconvenient is overcome by re-applying the test on the filtered data. To determine if the nonlinear causality relationships found are nonlinear in nature, we should apply the test to the residuals of the VECM (if the variables are cointegrated, otherwise we apply this test on the residuals of the VAR).

The main contribution of [27] consists of transferring the nonlinear causality test of [50] to a multivariate setting. By evaluating the densities at the sharpened data set, [27] guarantee the consistency of their test statistic. The sharpening procedure reduces the estimator bias and provides a consistent test statistic [35]. Following the notation proposed by [27], if we consider , the null hypothesis of no causality running from I, controlling for W, is:

where the symbol ‘’ denotes equivalence in distribution, and ( = , ) is the number of lags of each variable. Therefore, the null hypothesis of Equation (8) states that consumption does not help predict future investment, controlling for the wage mass. Following the notation proposed by [27], we consider the compact shape = (, , ) so that the sharpened test statistic is:

where is a sharpened form of the local density estimator of a -variate vector : , where is a density estimation kernel, and is a sharpening map used to reduce the bias of the estimator whose explicit form depends on the order of bias reduction, determined by subscript p [27]. Reference [27] demonstrate that their sharpened test statistic converges in distribution to a standard normal distribution:

where is a consistent estimator of the asymptotic variance of , and is .

3. Empirical Results

Table 1 reports the unit root tests results. The unit root tests results indicate that the variables are not stationary in level at the 1% significance level. Besides, the first differences of the series are stationary at the 1% level. Therefore, the variables are integrated of order one at the 1% significance level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Augmented Dickey–Fuller and Phillips–Perron tests for unit root.

After testing for unit root, we apply the ARDL bounds test to investigate the existence of cointegration among the variables. We estimate the model with a constant and with a constant and a linear trend. In both specifications, the F-statistic values (11.67 and 7.91) are higher than the upper-bound critical values (5 and 5.85) at the 1% significance level. Therefore, the variables are cointegrated at the 1% level (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bounds F-statistic test for no cointegration. Dependent variable: Investment.

As a robustness check, we apply the Johansen and Juselius (1990) approach to test for cointegration between investment and consumption (controlling for the wage mass). We select the lag order that minimizes the BIC and the AIC, considering a lag length up to 12. We verify the absence of autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity in the residuals. Table A1 and Table A2 (in Appendix A) show that there are at most two cointegration vectors at the 5% significance level. Accordingly, our findings suggest the existence of cointegration among the three variables at the 5% level.

Table 3 reports the ARDL regression equation for both the long run and the short run. We observe a positive and statistically significant relationship between investment and consumption in the short and in the long run.

Table 3.

ARDL representation of the selected model for the level Investment equation.

As a robustness check, we estimate the parameters of the long-run equilibrium relationship between investment and consumption (controlling for the wage mass) by applying dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) and fully modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS). These estimators deal effectively with regressors’ endogeneity and serial correlation in the errors. The FMOLS and the DOLS estimated equations show that consumption has a positive and statistically significant long-run effect on investment (Table A3 in Appendix B), thus confirming the results of the ARDL regression presented in Table A3. Since we use the variables in logarithms, these coefficients can be interpreted as long-run elasticities.

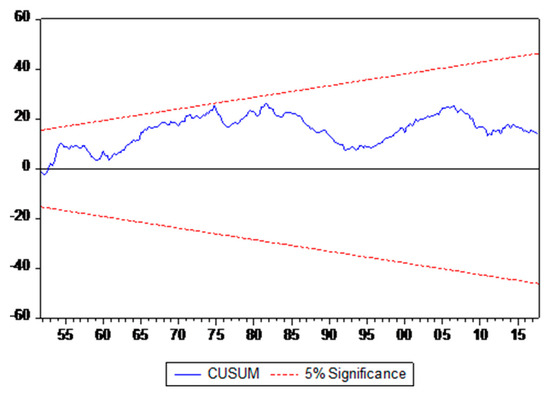

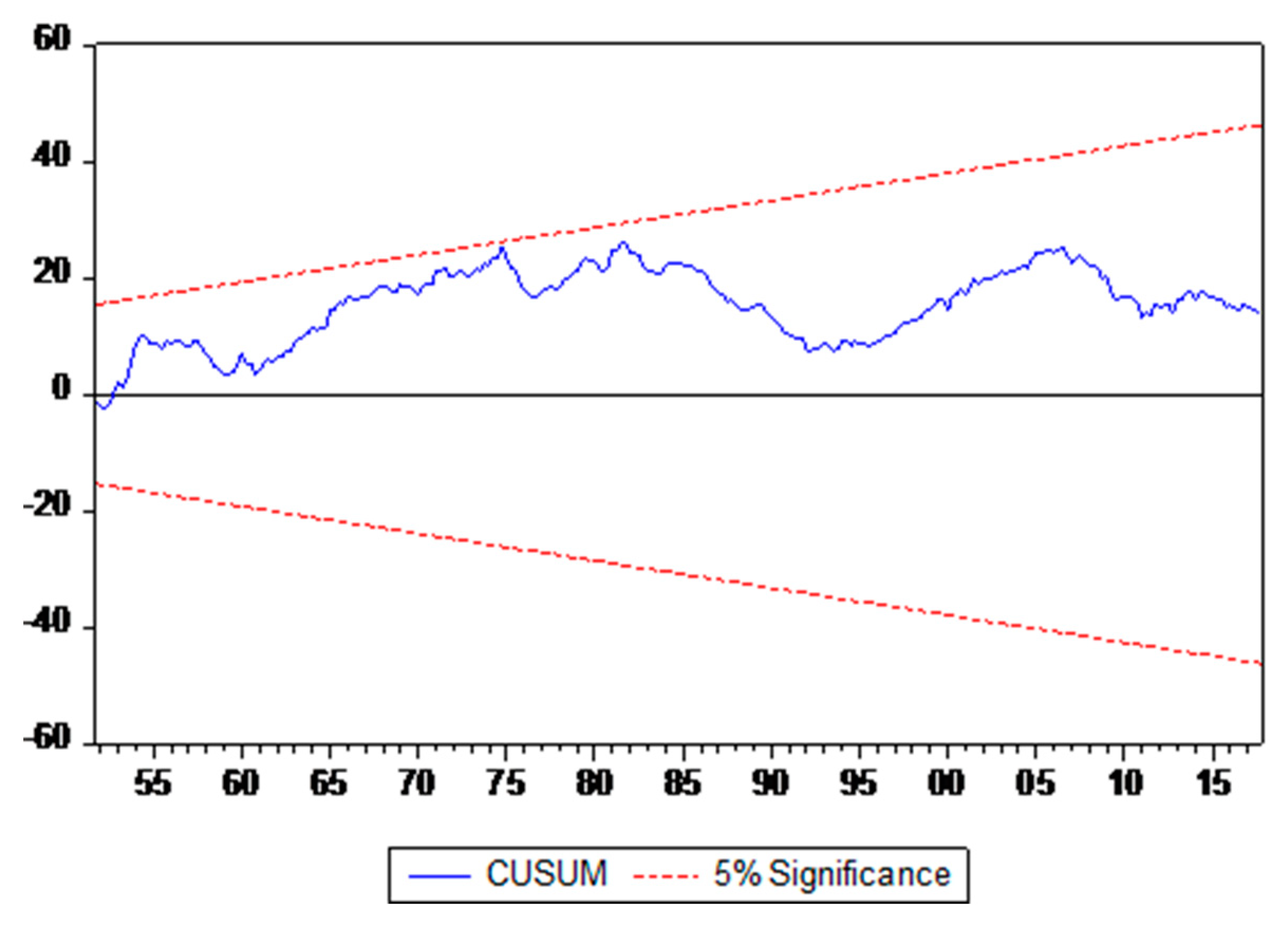

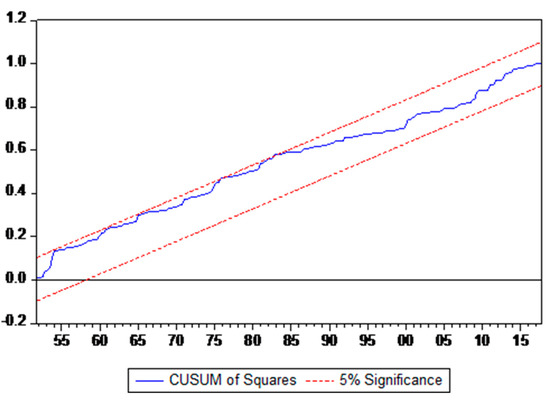

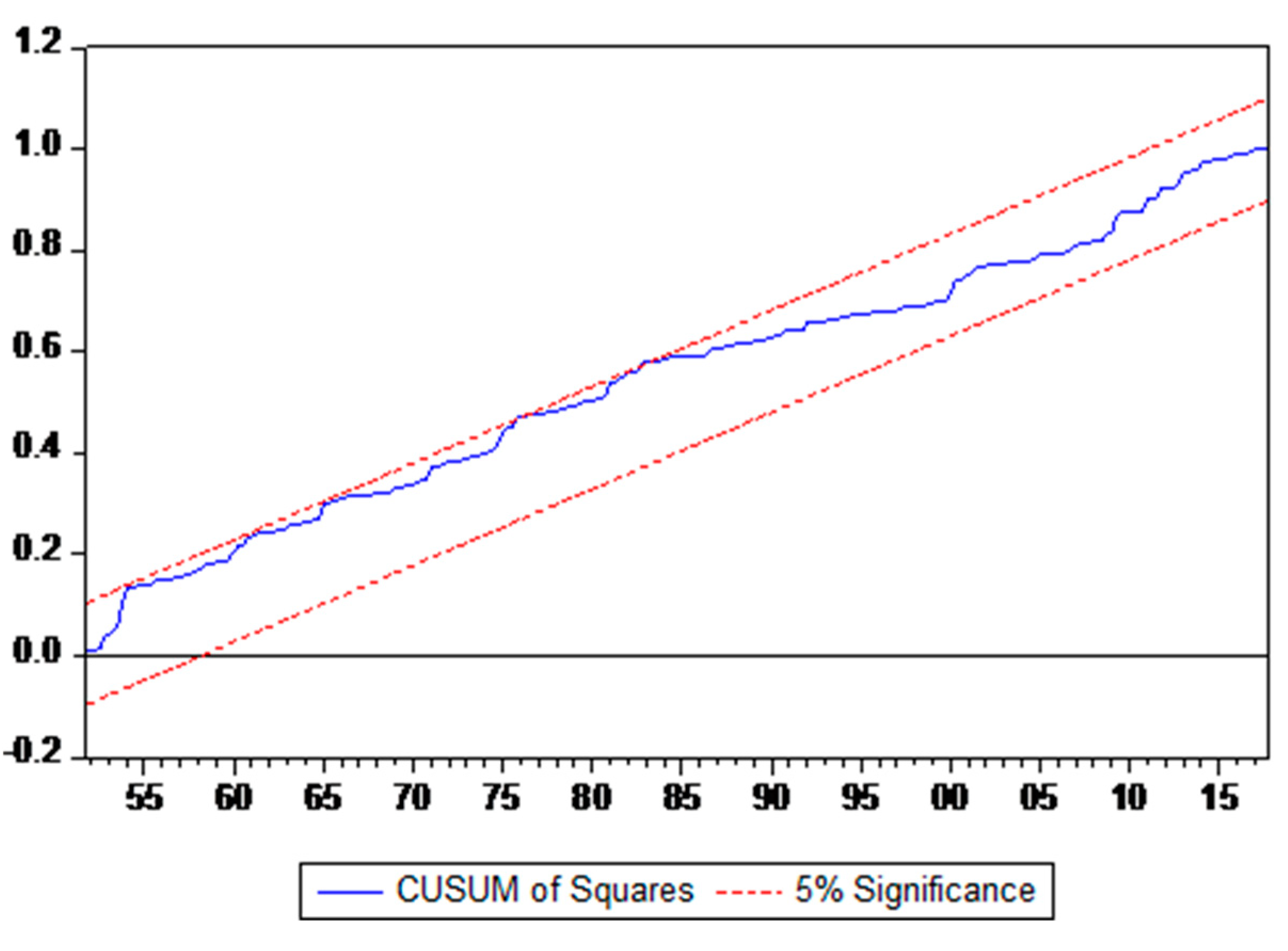

We apply standard diagnostic tests to ensure that the ARDL model is well specified. We conduct serial correlation, normality, and heteroscedasticity tests. The Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test indicates the absence of serial correlation in the residuals at the 5% level. The Harvey test of heteroscedasticity suggests no heteroscedasticity. The Jarque-Bera test shows that the residuals of the model are normally distributed. Finally, we apply the cumulative sum of the recursive residuals tests (hereafter CUSUM and CUSUMSQ), proposed by [51] to examine the stability of the parameters of the ARDL model. The graphs plots are displayed in Figure A1 and Figure A2 (Appendix C). The CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests indicate stability in the coefficients. Figure A1 and Figure A2 show that the blue line does not cross the 5%-critical-value lines (red lines); therefore, the ARDL coefficients are stable at the 5% level. In Table 3, we only show the ARDL regression output of the model with a constant, but we obtain similar results in all the tests when we apply them to the model with a constant and a linear trend.

Next, we apply linear Granger-causality tests between consumption and investment. We know that investment affects output and, therefore, consumption (and the wage mass). What we investigate through the linear Granger-causality approach, however, is whether consumption is the primum movens with respect to investment.

Through the error correction representation of the ARDL model of Equations (6) and (7), we can test for short-run and long-run Granger-causality between the variables. The standard Wald test indicates that the coefficients of consumption in the investment equation are positive and statistically jointly significant, indicating the existence of positive causality running from consumption to investment. On the other hand, the coefficients of investment in the consumption equation (Table A4 in Appendix D) are not statistically jointly significant. It indicates that there is positive linear causality running unidirectionally from consumption to investment in the short run. The coefficients of the error correction term in both equations are negative and significant. It indicates, on the one hand, that consumption and the wage mass jointly Granger-cause investment in the long run, and, on the other hand, that investment and the wage mass jointly Granger-cause consumption in the long run. Nevertheless, since investment does not Granger-cause consumption in the short run, according to the notion of long-run causality of [52], we conclude that there is linear long-run Granger-causality running unidirectionally from consumption to investment.

As a robustness check, we carry out the linear Granger-causality test of [44]. The optimal lag length, , is chosen by the SIC and AIC. The results of the [44] test also suggest that there is positive linear causality, running unidirectionally from to , at the 5% significance level (Table A5 in Appendix D).

We also estimate a VECM through the traditional approach of [45] (Table A6 in Appendix D) for robustness. The VECM equation with as dependent variable presents an error correction term of −0.13 with a p-value of 0.00. On the other hand, the VECM equations with and as dependent variables present positive error correction terms parameters with p-values of 0.08 and 0.29, respectively. Then, the weak exogeneity test indicates that investment is the only variable that in the event of any shock adjusts to the long-run equilibrium relationship. Thus, investment is the only weakly endogenous variable of the system at the 5% significance level. We also employ the VECM to test for short-run linear causality between investment and consumption. The coefficients of the VECM and the Wald tests indicate positive linear Granger-causality running unidirectionally from consumption to investment at the 5% significance level. Therefore, these results coincide with those of the ARDL model presented in Table 3.

After applying linear Granger-causality tests to the raw data, we carry out the nonlinearity test on the VECM residuals. This detects if the causal relationship found in the linear analysis prevails. As expected, the linear causal relationship previously found disappears after VECM filtering. We can conclude, therefore, that the linear causality relationship between and is due to first moment effects (i.e., causality in the mean).

On the other hand, the BDS test results on the VECM residuals reveal a nonlinear structure in the residuals (Table 4). Therefore, it becomes necessary to implement the nonlinear Granger-causality test.

Table 4.

BDS test results.

Since the DW test of nonlinear causality assumes stationarity of the underlying data, we apply the test on the first-differenced series. Following the two-step process suggested by [27], we first apply the test on the raw data to detect the presence of nonlinear causal relationships among the variables. We use a lag order of one and employ the bandwidth method suggested by [27] to estimate the bandwidth of the test, which resulted in We find nonlinear Granger-causality running unidirectionally, from to , at the 5% significance level (Table 5).

Table 5.

Diks and Wolski (2016) Nonlinear Granger-causality test.

Next, we apply the DW test on the filtered residuals of the VECM (because we have verified that the variables are cointegrated), to verify whether the nonlinear causal relationship between consumption and investment is genuinely nonlinear. The causal relationship previously found disappears after VECM filtering. It suggests that the causal relationship is not explained exclusively by the nonlinear components of the variables.

We now apply the same analysis but conditioning on Government Expenditure, . As proxy for , we employ “Real Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment, Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars, Quarterly, Seasonally Adjusted.” In this four-variable model, we use a lag length of one and the bandwidth method by [27] to estimate the bandwidth of the test, which resulted in After controlling for , the nonlinear causal relationship between and vanishes. According to [27], this finding indicates that drives the nonlinear causal relationship between and .

This result has economic sense and supports the statements of the GT. We interpret this in line with the idea that permanent aggregate demand guides investment decisions [11,12]: public expenditure guarantees households certain goods and services. Then, the dynamics of households’ consumption becomes sufficiently persistent to determine the evolution of private investment. Therefore, consumption sustains investment because public expenditure allows the former to have a sufficiently permanent trajectory to be considered as a guide for investment decisions.

4. Conclusions

This paper analyzes the relationship between investment and consumption that the General Theory (1936), by John Maynard Keynes, postulates. We test the empirical relationship between consumption, , and investment, with quarterly data from the US economy. We find cointegration and linear Granger-causality running unidirectionally from to in the US between 1947 and 2018. Nevertheless, this linear causal relationship dies out after VECM filtering, indicating that this causality relationship is significant only in the mean. The nonlinear analysis confirms this causality relationship, suggesting the existence of nonlinear causality running unidirectionally from to .

On the other hand, when we control for Public Expenditure, , the nonlinear causal relationship running from to disappears. According to [27], this finding indicates that drives the nonlinear causal relationship between and : in the absence of , would not nonlinearly cause . We interpret this in line with the idea that it is permanent aggregate demand that guides investment decisions [11,12]: without the presence of public expenditure, entrepreneurs would not consider that private consumption evolves in a sufficiently persistent way, and therefore it would not drive their investment decisions.

Our results contribute to the literate and are of special interest for policy makers in the United States. We find evidence of a positive equilibrium relationship between aggregate consumption and investment that the conventional literature on economics overlooks. We also recall that this long-run nexus and the causality relationship running unidirectionally from consumption to investment are sustained by public intervention in the economy through final public expenditure. Therefore, our results call for national economic policies aimed at incrementing public expenditure.

During the first decades after the Word War, in the United States and Europe prevailed the view that public intervention was desirable for promoting effective demand and economic growth. The redistribution of income, due to progressive taxation and especially through final public expenditure, was considered as favorable to the growth of ‘private consumption outlay’ [53]. Nevertheless, the well-known monetarist revolution of the 1970s, which brought back the main pre-Keynesian postulates, stated that public intervention would displace saving and investment and, therefore, would be detrimental for capital accumulation and growth. We believe that in this context, the results of our paper constitute an important contribution to the debate.

Author Contributions

J.P.-M. and C.M. conceived and designed the research; C.M. collected and processed the data; J.P.-M. analyzed the data. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the research grant Mediterranean Capitalism?: successes and failures of industrial development in Spain, 1720–2020, PGC2018 093896-B-100, directed by Jordi Catalan and financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy; and by the research grant FPI/1866/2016, financed by the European Social Fund and the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Tourism of the Balearic Islands, which is gratefully acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions that helped to improve the paper. We are also in debt with Victor Troster, Ferran Portella-Carbó, and Tomás Del Barrio for helpful comments and suggestions. Usual disclaimers apply.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Cointegration Tests

Table A1.

Johansen and Juselius cointegration test. Model with a constant and a trend. Dependent variable: Investment.

Table A1.

Johansen and Juselius cointegration test. Model with a constant and a trend. Dependent variable: Investment.

| Hypothesized No. of CE (s) | Unrestricted Cointegration Rank (Trace) | Unrestricted Cointegration Rank (Maximum Eigenvalue) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trace Statistic | 5% Critical Value | p-Value | Max-Eigen Statistic | 5% Critical Value | p-Value | |

| None * | 59.30 | 42.92 | 0.00 | 32.19 | 25.82 | 0.01 |

| At most 1 * | 27.11 | 25.87 | 0.04 | 21.14 | 19.39 | 0.03 |

| At most 2 | 5.97 | 12.52 | 0.46 | 5.97 | 12.52 | 0.46 |

Notes: This table presents the results of the cointegration test of Johansen and Joselius (1990). The null hypothesis states that there is no cointegration between the variables. The asterisk * denotes rejection of the null hypothesis at the 5% significance level. The trace test and the max-eigenvalue test indicate at most two cointegrating equations at the 5% level.

Table A2.

Johansen and Juselius cointegration test. Model with a constant. Dependent variable: Investment.

Table A2.

Johansen and Juselius cointegration test. Model with a constant. Dependent variable: Investment.

| Hypothesized No. of CE (s) | Unrestricted Cointegration Rank (Trace) | Unrestricted Cointegration Rank (Maximum Eigenvalue) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trace Statistic | 5% Critical Value | p-Value | Max-Eigen Statistic | 5% Critical Value | p-Value | |

| None * | 52.22 | 29.80 | 0.00 | 30.74 | 21.13 | 0.00 |

| At most 1 * | 21.48 | 15.49 | 0.01 | 18.06 | 14.26 | 0.01 |

| At most 2 | 3.42 | 3.84 | 0.06 | 3.42 | 3.84 | 0.06 |

Notes: This table presents the results of the cointegration test of Johansen and Juselius (1990). The null hypothesis states that there is no cointegration between the variables. The asterisk * denotes rejection of the null hypothesis at the 5% significance level. The trace test and the max-eigenvalue test indicate at most two cointegrating equations at the 5% level.

Appendix B. Long-Run Estimators

Table A3.

Dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) and fully modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS) long-run elasticities. Dependent variable: Investment.

Table A3.

Dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) and fully modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS) long-run elasticities. Dependent variable: Investment.

| DOLS Method | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regressors | Model with a Constant | Model with a Constant and a Linear Trend | ||||||

| Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | |

| Consumption | 1.50 * | 0.35 | 4.32 | 0.00 | 2.50 * | 0.62 | 4.01 | 0.00 |

| Wage Mass | −0.37 | 0.40 | −0.92 | 0.36 | −0.99 | 0.50 | −1.95 | 0.05 |

| Constant | −2.91 * | 0.32 | −9.07 | 0.00 | −5.70 * | 1.50 | −3.81 | 0.00 |

| Trend | - | - | - | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.92 | 0.06 |

| FMOLS method | ||||||||

| Regressors | Model with a constant | Model with a constant and a linear trend | ||||||

| Coefficient | Std. Error | t-statistic | p-value | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-statistic | p-value | |

| Consumption | 0.50 * | 0.21 | 2.37 | 0.02 | 1.49 * | 0.39 | 3.87 | 0.00 |

| Wage Mass | 0.74 * | 0.24 | 3.04 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.72 | 0.47 |

| Constant | −3.36 * | 0.23 | −14.51 | 0.00 | −6.59 * | 1.22 | −5.39 | 0.00 |

| Trend | - | - | - | - | 0.00 * | 0.00 | −2.73 | 0.01 |

Notes: This table presents the results of the DOLS and FMOLS estimators. The selection of lags is carried out by minimizing the AIC. The asterisk * indicates statistical significance at the 5% significance level.

Appendix C. Parameters Stability Tests

Figure A1.

Plots of CUSUM of recursive residuals.

Figure A1.

Plots of CUSUM of recursive residuals.

Figure A2.

Plots of CUSUM of squared recursive residuals.

Figure A2.

Plots of CUSUM of squared recursive residuals.

Appendix D. Linear Granger-Causality Tests

Table A4.

ARDL representation for the selected model for the level equation.

Table A4.

ARDL representation for the selected model for the level equation.

| Unrestricted Error Correction Model Dependent Variable: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value |

| −0.20 | 0.07 | −3.00 | 0.00 | |

| 0.31 | 0.06 | 5.10 | 0.00 | |

| 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.35 | 0.02 | |

| −0.10 | 0.06 | −1.75 | 0.08 | |

| 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.92 | |

| 0.40 * | 0.05 | 7.74 | 0.00 | |

| 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.82 | 0.07 | |

| −0.20 * | 0.05 | −3.92 | 0.00 | |

| −0.17 * | 0.05 | −3.22 | 0.00 | |

| CointEq(−1) | −0.02 * | 0.00 | −7.62 | 0.00 |

| Long-run coefficients. Dependent variable: | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-value |

| Investment | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.93 |

| Wage mass | 1.06 * | 0.37 | 2.85 | 0.00 |

| Constant | −0.08 | 1.09 | −0.07 | 0.94 |

Notes: This table presents the ARDL representation for the selected model for the level equation. The table shows the unrestricted error correction model with as dependent variable and the coefficients of the long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables. The asterisk * indicates statistical significance at the 5% level.

Table A5.

Toda and Yamamoto linear Granger-Causality test.

Table A5.

Toda and Yamamoto linear Granger-Causality test.

| Dependent Variable: Investment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | p-Value |

| Consumption | 101.91 * | 5 | 0.00 |

| Wage mass | 4.48 | 5 | 0.48 |

| All | 131.00 | 10 | 0.00 |

| Dependent variable: Consumption | |||

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | p-value |

| Investment | 8.36 | 5 | 0.14 |

| Wage mass | 7.74 | 5 | 0.17 |

| All | 26.66 | 10 | 0.00 |

Notes: This table presents the results of the Toda and Yamamoto (1995) causality test. The asterisks * denotes rejection of the null hypothesis of no causality at the 5% significance level.

Table A6.

Results of the VECM regressions.

Table A6.

Results of the VECM regressions.

| Regressors | Dependent Variable | Dependent Variable: | Dependent Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-Value | Coefficient | p-Value | Coefficient | p-Value | |

| −0.14 * | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.29 | |

| 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.06 * | 0.00 | |

| 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.44 | |

| −0.06 | 0.36 | −0.03 * | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.49 | |

| −0.15 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.97 | −0.02 | 0.15 | |

| −0.10 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.24 | |

| 2.63 * | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.48 * | 0.00 | |

| 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.54 | |

| 0.03 | 0.94 | 0.10 | 0.19 | −0.04 | 0.66 | |

| 1.41 * | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.88 | 0.10 | 0.25 | |

| 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.74 | −0.01 | 0.86 | |

| 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.33 | −0.06 | 0.43 | |

| −0.26 | 0.43 | −0.15 * | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.62 | |

| −0.17 | 0.60 | −0.05 | 0.45 | 0.17 | 0.03 | |

| −0.32 | 0.33 | −0.01 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.66 | |

| −0.15 | 0.64 | −0.04 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.73 | |

| const. | −0.03 * | 0.00 | 0.01 * | 0.00 | 0.00 * | 0.52 |

Notes: This table presents the VECM estimated within the framework of the Engle and Granger (1987) approach. The asterisk * indicates statistical significance at the 5% level.

References

- Keynes, J.M. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money; Macmillan: London, UK, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Vercelli, A.; Sordi, S. Genesis and Evolution of the Multiplier-Accelerator Model in the Years of High Theory; University of Sienna: Siena, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harrod, R.F. An Essay in Dynamic Theory. Econ. J. 1939, 49, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, P.A. Interactions between the Multiplier Analysis and the Principle of Acceleration. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1939, 21, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J. A Contribution to the Theory of the Trade Cycle; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, O.; Dal-Pont Legrand, M. The instability principle revisited: An essay in Harrodian dynamics. Eur. J. Hist. Econ. Thought 2014, 21, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, O. Tackling the instability of growth: A Kaleckian-Harrodian model with an autonomous expenditure component. Camb. J. Econ. 2015, 39, 1351–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, M. Convergence Towards the Normal Rate of Capacity Utilization in Neo-Kaleckian Models: The Role of Non-Capacity Creating Autonomous Expenditures. Metroeconomica 2016, 67, 172–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, F.; Freitas, F.; Bhering, G. The Trouble with Harrod: The fundamental instability of the warranted rate in the light of the Sraffian Supermultiplier. Metroeconomica 2018, 70, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejuan, Ó. Paths of accumulation and growth: Towards a Keynesian long-period theory of output. Rev. Political Econ. 2005, 17, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejuán, Ó. Hidden links in the warranted rate of growth: The supermultiplier way out. Eur. J. Hist. Econ. Thought 2017, 24, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatwell, J. The long-period theory of employment. Camb. J. Econ. 1983, 7, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walras, L. Elements of Pure Economics: Or the Theory of Social Wealth, 1954th ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Garegnani, P. Quantity of capital. In Capital Theory; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1990; pp. 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cesaratto, S. The saving-investment nexus in the debate on pension reforms. In Economic Growth and Distribution: On the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations; Savadori, N., Ed.; University of Pisa: Pisa, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Garegnani, P. The Problem of Effective Demand in Italian Economic Development: On the Factors that Determine the Volume of Investment. Rev. Political Econ. 2015, 27, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, M.; Horioka, C. National saving and international capital flows. Econ. J. 1980, 90, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, J.; Kulasi, F.; Smith, R. Current Account Solvency and the Feldstein—Horioka Puzzle. Econ. J. 1996, 106, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.; Huang, H.-C. The smooth-saving-retention-coefficient with country-size. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2006, 13, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, J. Solving the Feldstein-Horioka Puzzle With Financial Frictions. Econometrica 2010, 78, 603–632. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, P.K.; Narayan, S. Testing for capital mobility: New evidence from a panel of G7 countries. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2010, 24, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.H. The Feldstein-Horioka Puzzle and Spurious Ratio Correlation. J. Int. Money Financ. 2012, 31, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-W.; Shen, C.-H. Revisiting the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle with regime switching: New evidence from European countries. Econ. Model. 2015, 4, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Li, H. Time-varying saving–investment relationship and the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle. Econ. Model. 2016, 53, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, J.B. Are saving and investment cointegrated? The case of Malaysia (1965–2003). Appl. Econ. 2007, 39, 2167–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvoskin, A.; Petri, F. Again on the Relevance of Reverse Capital Deepening and Reswitching. Metroeconomica 2017, 68, 625–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diks, C.; Wolski, M. Nonlinear Granger Causality: Guidelines for Multivariate Analysis. J. Appl. Econ. 2016, 31, 1333–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, A.; Marglin, S. Unemployment and the real wage: The economic basis for contesting political ideologies. Camb. J. Econ. 1990, 14, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockhammer, E. Rising inequality as a cause of the present crisis. Camb. J. Econ. 2015, 39, 935–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynamon, B.Z.; Fazzari, S.M. Inequality, the Great Recession and slow recovery. Camb. J. Econ. 2016, 40, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecker, R.A. Wage-led versus profit-led demand regimes: The long and the short of it. Rev. Keynes. Econ. 2016, 4, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palley, T.I. Wage- vs. profit-led growth: The role of the distribution of wages in determining regime character. Camb. J. Econ. 2017, 41, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, M. The origins and evolution of the debate on wage-led and profit-led regimes. Eur. J. Econ. Econ. Policies Int. 2017, 14, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, E.; Dickey, D.A. Testing for unit roots in autoregressive-moving average models of unknown order. Biometrika 1984, 71, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Perron, P. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econ. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K. The saving and investment nexus for China: Evidence from cointegration tests. Appl. Econ. 2005, 37, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. Identifying restrictions of linear equations with applications to simultaneous equations and cointegration. J. Econ. 1995, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. Modelling of cointegration in the vector autoregressive model. Econ. Model. 2000, 17, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juselius, K. The Cointegrated VAR Model: Methodology and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.-C. Electricity Consumption and Economic Growth: Evidence from 17 Taiwanese Industries. Sustainability 2016, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 1969, 37, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Testing for causality: A personal viewpoint. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 1980, 2, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, H.Y.; Yamamoto, T. Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. J. Econ. 1995, 66, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.F.; Granger, C.W.J. Co-Integration and Error Correction: Representation, Estimation, and Testing. Econometrica 1987, 55, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y. Analysis of the Dynamic Relationship between Fluctuations in the Korean Housing Market and the Occurrence of Unsold New Housing Stocks. Sustainability 2017, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiszeder, P.; Orzeszko, W. Nonlinear Granger causality between grains and livestock. Agric. Econ.-Czech 2018, 64, 328–336. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, W.A.; Hsieh, D.A.; LeBaron, B.D. Nonlinear Dynamics, Chaos, and Instability: Statistical Theory and Economic Evidence; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Broock, W.A.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Dechert, W.D.; LeBaron, B. A test for independence based on the correlation dimension. Econ. Rev. 1996, 15, 197–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diks, C.; Panchenko, V. A new statistic and practical guidelines for nonparametric Granger causality testing. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2006, 30, 1647–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Durbin, J.; Evans, J.M. Techniques for Testing the Constancy of Regression Relationships Over Time. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1975, 37, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Wolski, M. Human capital, energy and economic growth in China-Evidence from multivariate nonlinear granger causality. Energy Econ. 2016, 68, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, W. Full Employment in a Free Society George Allen 86 Unwin; George Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1944. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).