1. Introduction

Cultural heritage is the cornerstone of local, regional, national, and European identity [

1]. It is a common value and a shared asset that is not only an integral part of the cultural sector but also a significant element and incentive for the development of tourism and other industries. Cultural heritage includes tangible—material, physical, and intangible—immaterial, dynamic, living heritage elements that are inextricably correlated. As a whole, tangible and intangible cultural heritage are in a complex connection depending on the natural heritage and environment [

2]. Cultural reality represents a dynamic set of living and active processes, whereby it comprises tangible and intangible heritage to be considered as a whole. In this sense, cultural heritage does not only represent tangible monuments and collections of objects, but also the intangible traditions and living expressions inherited from our ancestors. Intangible cultural heritage relates to the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, and skills—as well as the instruments, objects, artifacts, and cultural spaces associated therewith—that communities, groups, and in some cases individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage [

2].

The Athens Charter [

3] was first to propose the idea of a common world heritage. It was followed by the Venice Charterand the creation of the International Council on Monuments and Sites ICOMOS [

4], and finally the World Heritage Convention [

5]. Summarizing the catastrophic consequences of the two world wars, the comprehension of world heritage and idea for its safeguarding, conservation, and protection were strongly oriented on material aspects of heritage: built structures, great works of art and architecture, archeological and natural sites. This Decartian view on culture, characteristic of Western philosophical and cultural thinking, remained dominant until the late 20th century. In the late 1980s, challenging questions were raised in terms of intangible cultural heritage, as a new modality of cultural heritage existence [

6].

Moreover, awareness of the importance, value, and the need for the preservation of intangible cultural heritage is in the focus of the world and socially concerned goals of the humanity in the new millennium. Taking into consideration the challenges of the 21st century in terms of globalization, social transformations, frequent threats from terrorism and armed conflicts, disappearance and destruction of the intangible cultural heritage, and the lack of resources for its safeguarding, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) drafted and adopted the

Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003 [

2] with the aim of establishing normative instruments. Therefore, the UNESCO Convention is an area of particular interest for our research, because of the understanding of cultural heritage, the methodology of work, and the instruments it uses to protect the cultural heritage, which has changed very much in the last decades. The adopted conventions, declarations, and instrumental legal acts emphasize the importance of an integrated approach in addressing the problems related to the conservation, protection, use, and transmission of cultural heritage. To this end, the cooperation of various participants from different disciplines and domains of activity is emphasized as one of the most critical conditions in strengthening social identity and diversity, and in the achievement of local, regional, and international cultural heritage goals, as a key factor for cultural sustainability and sustainable development in general [

1]. An integrated approach to the protection of cultural heritage implies smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth, and therefore it can be a powerful driver for local and regional development on a national level, which is aimed at promoting sustainable, responsible, and high-quality cultural tourism [

1].

Regarding tourism management, one of the most essential elements is to identify the potential of a particular cultural heritage to manage tourism in an innovative, cost-effective, and at the same time sustainable way. Although Serbia has based its tourism strategy primarily on the material (tangible) cultural elements for decades, parts of rich Serbian intangible heritage have been in focus in the past few years, and are still at the very beginning of their perceptions and potentials in terms of drawing the attraction of domestic and foreign tourists [

7]. One of the reasons for the reduced utilization of intangible cultural resources in tourism in Serbia is that the Serbian cultural and scientific public is still at the stage of research processes focused mainly on the cooperation of various participants solely within the cultural sector. In a few cases, collaboration with the Tourist Organization of Serbia (TOS) was also carried out, but actual intangible cultural values have not yet found their full expression for modernizing the tourist offer in Serbia and complementing it through an unbreakable bond with material and physical tangible heritage.

Cultural tourism is one of the oldest forms of tourism. As early as medieval times, there were various religious pilgrimages: annual cultural events that represented the motive of tourist trips. According to the definition that was adopted by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) at the 22nd Session of the General Assembly held in Chengdu in China, cultural tourism is a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience, and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions or products of a specific tourism destination [

8]. Cultural heritage tourism includes the cultural, historical, and natural experiences of the places and products. In that sense, we can speak of different cultural attractions or products, such as the intellectual, spiritual, and emotional features of a society that encompasses art and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries, and the living cultures with their lifestyles, value systems, beliefs, and traditions [

8].

According to Richards [

9], tourists’ motivation for cultural tourism can be a culture of consumerism, low and high desire for cultural experiences, the tendency for learning, satisfaction, and revisiting intentions. By highlighting the interrelations between tangible and intangible cultural heritage, cultural tourism today should be understood in an inclusive spirit as a means of communication between different stakeholders that reinforce authentic values of places and the social culture of people. In that sense, the interpretation of cultural heritage is not only a set of historical information collected in the form of written texts about individual monuments. Today, tourists are active participants who seek experiences and gather knowledge in a personally involved and active way.

Besides cultural tourism, local governments have been employing place-branding strategies during the last few decades for improving attractiveness and image in order to create additional value in place [

10], and thus achieve advantages in competition with other cities in entrepreneurial shifts in urban governance, as Harvey [

11] and Jessop [

12] have highlighted. According to Boisen, Terlouw, Groote, and Couwenberg [

13], place branding has gone through transformations from (1)

place promotion—which focuses on generating favorable communication; (2)

place marketing—which deals with balancing supply and demand; and finally, (3)

place branding—which is mainly about creating, sustaining, and shaping a favorable place identity. Therefore, central to place branding are the issues of value creation and identification. As Kapferer suggests [

14], a brand can be perceived as something that gives meaning and creates value to the product while defining its identity. Furthermore, Ashworth [

15] underlines that place branding deals with discovering or creating uniqueness, which can differentiate a specific place from the others in order to gain competitive brand value. Regarding the practical utilization of place-branding strategies on the local urban level, the setup we used is practically the same as the one proposed by Ashworth [

15]. He claims that the three main local planning instruments are: (1)

personality association, in which places associate themselves with an individual from history, the arts, or even mythology; (2)

the visual qualities of buildings and urban design, which could involve flagship buildings, signature urban design, and even whole districts; and, (3)

event hallmarking, in which the place organizes cultural or other events for a wider recognition and specific brand associations. A challenging area in the field of place-branding processes has been suggested by Govers [

16], who considers that the shape and substance of places are produced by residents. Therefore, the brand of a place should be built on the sense of place and identity of the local population and other social actors. Furthermore, the interplay between place branding and identity, as recognized by Karavatzis and Hatch [

17], is a dialogue between stakeholders in the dynamic interaction of internal definitions of identity and external views of the image of the place, and arising from the interaction between the two. Therefore, Karavatzis and Hatch [

17] underline that place branding and identity consists of four main features: expressing the place’s cultural understandings, mirroring impressions and expectations, reflecting and adding new meanings and symbols, and leaving an impact on others.

The concepts of cultural tourism and place branding represent contemporary challenges for local governments in the entrepreneurial context in regeneration processes. One challenge is how to disclose the uniqueness of a particular place and yet achieve a competitive advantage. The other challenge is how to present local identities, touristic assets, and cultural attractions to tourists and make them a part of the extraordinary experiences.

That is why it is of great importance that the development of cultural tourism strategies at heritage sites should involve collaboration and teamwork with various stakeholders regarding the heritage assets and its possible adaptive reuse [

18]. This is in line with the discursive inclusivity in the participatory governance of cities and the communicative–collaborative planning model, which focuses on the communication between all stakeholders as a tool for reshaping political powers [

19,

20]. In the communicative–collaborative model, according to Innes [

21], various interests should take part in the communication for coming to a consensus concerning goals for the planning process. Healey [

20] stresses that reaching consensus about future actions through discussion is vital for achieving mutual understanding. Therefore, the knowledge and information obtained through such a process are not scientifically known in advance, and are created in relation with the specific opportunities found in the local context. Subject–subject relation is understood here as a process in which all actors define a problem together and, as a result, they become experts as well [

22]. Therefore, involving stakeholders in a participative way requires not only planning experts with political skills for negotiation, but institutions and forums as well. Additionally, the process of collaboration between higher educational institutions and municipalities, along with various representatives from public institutions, can have an impact on building capacity at the local level [

23].

Case studies of Smederevo and Golubac fortresses represent notable examples of how cultural and natural heritage elements can be a source of aesthetic experiences. The aesthetic level of communication is a conscious, cultural layer that transmits ideas within a society, epoch, or group of people [

24]. Accordingly, it is possible to use the environmental aesthetic approach as the basis for support for the creation of inclusive touristic strategies. Environmental aesthetics is based on the principles of sustainability and appreciation of natural, human, and human-influenced environments [

25]. It explores the aesthetic positions of balancing relationships between people and their environment—both natural and human—through the exploitation of resources and technological development that does not disturb the natural, sociological, and economic system [

26].

The significance of environmental aesthetics for cultural heritage tourism is found in experiences that are related to the emotional uniqueness that tourists feel during the consumption of some cultural asset, but at the same time, environmental aesthetics is a constructive factor of the spirit of the place [

27]. The authentic spirit of the place of the Smederevo and Golubac fortresses not only represents the potential driving force of tourism in this area, but also contributes to the rehabilitation and renewal of forgotten knowledge of heritage and its promotion through modern branding techniques and methods of cultural management. In this sense, environmental aesthetics are of paramount importance for place branding, since they explain the theoretical and practical sense of place, atmosphere, and the cultural components of certain places.

Environmental aesthetics emphasize the most important fact of the environmental approach: natural and human or human-influenced environments do not exist separately; they are in a mutual relationship and coexist as such [

28]. The environmental aesthetics approach in urban design and architecture stresses the appreciation, preservation, restoration, maintenance, improvement, and conservation of all environments—natural, urban, and social—as one of the most current conditions of its ethical, aesthetic, and humanistic achievement [

29].

Furthermore, as Cooper, Brady, Steen, and Bryce [

30] claim, the interpretation of cultural heritage includes spiritual and aesthetic evaluations of nature that are an anthropogenic vision of natural beauty. In compliance with the environmental aesthetics principles, Harrison [

31] argues that the natural and cultural heritage of national parks cannot be separated. Divisions between nature and culture are invented by academic experts and sociopolitical institutions. For example, Dai people who live in villages in China do not make

nature–culture difference in their everyday lives [

32]. In order to feel the aesthetic emotions of the sublime, they witness nature and culture as complementary and inseparable. This is a cross-cultural perspective that is aligned with the multicultural vision of world heritage, which favors the great importance of nature–culture interlinks [

33].

In the case of cultural tourism, we can agree with Arnold Berleant, who developed the idea of aesthetic engagement. He considers that environmental perception is in the quality of engagement of our senses in perception—that is, participation in environmental experience [

34]. Likewise, according to Böhme, the atmosphere in architecture is created through a complex relation of the object—formal and informal characteristics of architecture—and the subject—audience, users—that makes the perception and is brought into a certain emotional state [

35]. According to the European Union (EU) Commission Regulation, natural heritage is often crucial for the shaping of artistic and cultural heritage. Heritage conservation should consequently combine natural heritage with cultural heritage [

36].

Cultural heritage tourism could also be seen as environmental nature tourism, where the tourism industry supports the conservation and safeguarding principles of natural, built, and intangible heritage [

37]. On the other hand, aesthetic beauty and design have an important role in tourist destinations, and could be used in order to renew weak relationships between culture, heritage, inhabitants, and the environment [

38]. In addition to economic and social benefits, cultural tourism could have a very positive impact on environmental aesthetic experiences and cultural heritage safeguarding. As Daniela Angelina Jelinčić claims [

39], psychological and neuroscientific approaches to the creation of aesthetical experiences results in powerful traces in tourist memories. Cultural heritage tourism could also be interpreted as creative tourism that particularly highlights intangible heritage values through collaboration, exchange, and learning from local inhabitants, craftsmen, and artisans [

40]. Following the idea of a

creative project, cultural heritage tourism could be of great significance for the survival of traditional skills, knowledge, and practices.

Having lost their original military purpose in the 19th century, the Smederevo and Golubac fortresses are nowadays living evidence of history and social culture, created as a product of the synergistic action between man and nature. These fortresses form part of the urban, natural, and sociocultural landscape that represents the evolutionary development of a society that has inhabited the region of the Danube River throughout history. Therefore, they represent an important element in the formation of the cultural identity of the Smederevo and Golubac regions, and, at a higher level, they are an essential element of the historical and national Serbian identity [

41]. The Smederevo and Golubac fortresses have been under protection since 1979 as a national property of exceptional importance. The Smederevo fortress was included in the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List in 2010 for possible nomination. This paper presents how the cultural potentials of the Smederevo and Golubac fortresses and intangible heritage in their respective territories were used for the creation of place-branding strategies and urban design projects exercised through the educational projects in cooperation between the University of Belgrade—Faculty of Architecture and local governments in Serbia.

Consequently, through the cases presented in this paper, we have tried to answer the main question that arises and highlights the difference between tangible and intangible cultural heritage, referring to Harrison and Rose [

42]: How can intangible assets be adequately protected when they exist only in minds, traditions, stories, and ephemeral practices? We offered an answer that encompassed cultural, environmental, social, and economic values through case studies of the Smederevo and Golubac fortresses by treating their tangible and intangible resources as a unique amalgam. In accordance with the principles of UNESCO and the ICOMOS framework, we suggest that rigid procedures that separate and accentuate division between tangible and intangible characteristics of the world cultural heritage should be neglected. More often than not, the intangible, non-material aspect of culture cannot be separated from the material and physical heritage. Case studies of the Smederevo and Golubac fortresses underline our thesis that both tangible and intangible heritage establish cultural identity.

2. Research Methods and Materials

The general methodology and research design used in this paper are based on the case study method with the examples of Smederevo and Golubac fortresses on the Danube River in Serbia. The research design strategy for the cases of Golubac and Smederevo was to include different stakeholders’ needs and analyze multiple levels of collaboration and communication processes between the local community and municipality representatives, cultural institutions, touristic stakeholders, experts, and professionals through educational projects. The main goal of such an approach was that the research findings could contribute to the policy debate, as argued by Farthing [

43], in a way that research within the planning discipline frames different conceptions and perspectives of the social world, including the recognition of values that shape the research process, as well as knowledge as socially constructed, and the discipline of planning as political. Framed in such a way, the results of the research are intended to highlight possible research directions in the field of cultural tourism development and intangible safeguarding practices, and be used in the future cultural, touristic, environmental, and branding development of the Lower Danube region in practice.

In the introductory part of the paper, we have used theoretical research and a literature review from different disciplines of culture, tourism, governance, and planning in order to better understand and further deepen the relations among specific subfields of cultural heritage, environmental aesthetics, tourism management, cultural tourism, place branding, and planning models and concepts. The method of content analysis was used in different research phases. It included analysis of the various documentation types—conventions, laws, reports, plans, literature, documents, photo documentation, and educational projects—in order to enable the key analytical elements and arrange case studies.

We came to the conclusion that the best method for our investigation of the use of cultural heritage for place branding in educational projects was the case study method. Our reasons for using the case study method bears a close resemblance to Flyvbjergs’ [

44] justification of the benefits of the case study qualitative method research option, in that it can be an outstanding selection for real-life situations, since it can test views in relation to phenomena as they disclose in practice. Additionally, according to Yin [

45], case studies are an approach that is useful for more in-depth and more detailed investigation when it is necessary to answer how and why questions emphasizing the reliability of the theoretical and practical framework primarily based on the context analysis of a distinctive situation: in our case, the two fortresses on the Danube River.

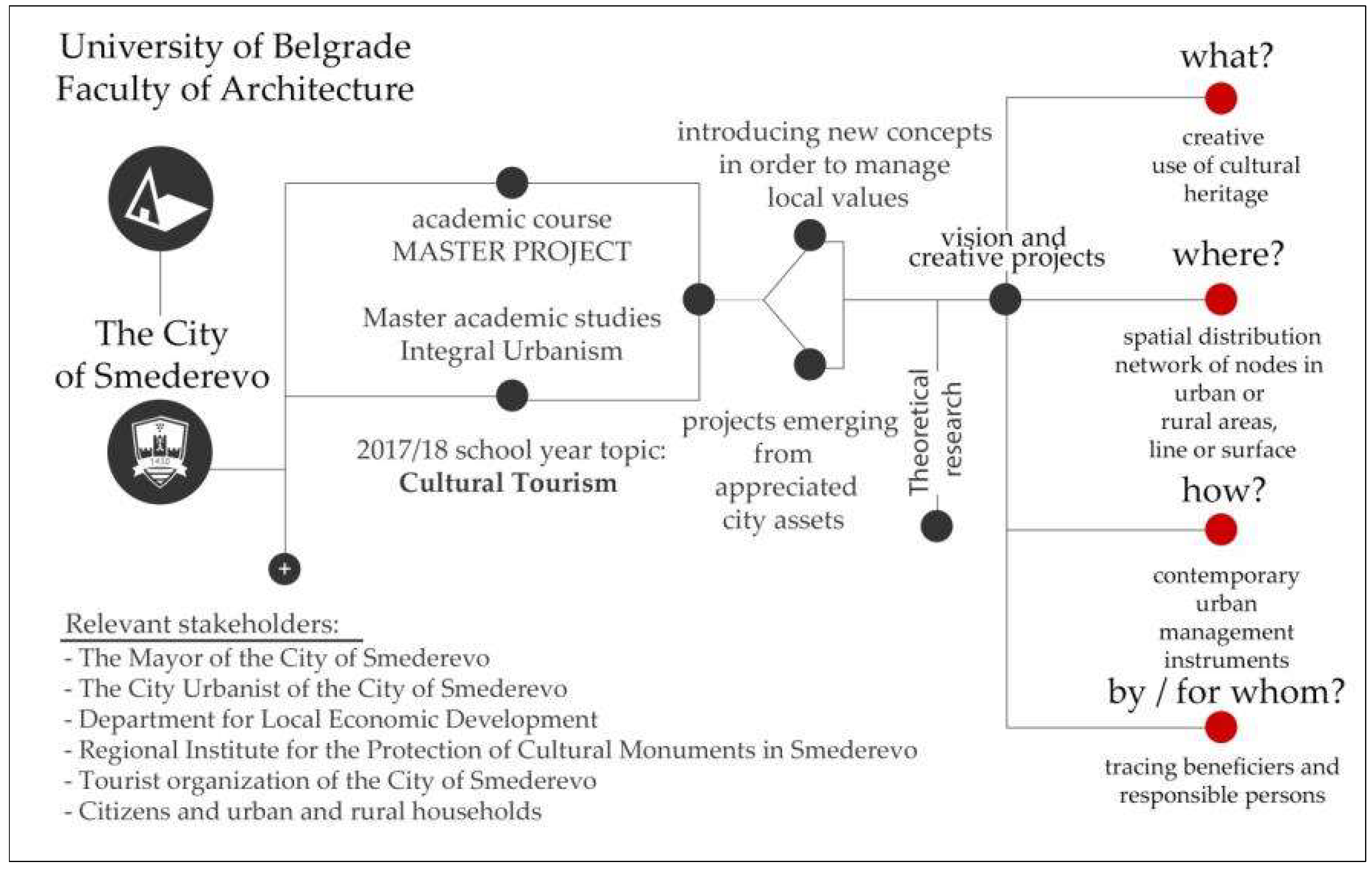

The case study method has proved to be suitable for this type of research, since it focuses on describing the historical development phases of cultural tangible and intangible heritage of case studies in question, their economic, environmental, and social context, as well as the processes of cooperation between academia and local governments, communities, and other stakeholders in educational projects. The two cases of the Golubac and Smederevo fortresses are examined as an empirical phenomenon in their whole, regarding the interrelations of their cultural, economic, touristic, environmental, and historical characteristics. The unit of analysis that has been chosen as the basis for the case studies includes a review of the educational projects realized at the University of Belgrade—Faculty of Architecture in 2008–2010 for the Golubac case, and in 2018 for the Smederevo case. Educational projects offer a case-study database and theoretical–empirical platform that include documents, work notes, interviews, design and research materials, narratives and observations, etc.

The main research methods for the case study research were a review of primary and secondary sources—conventions, laws, reports, plans, literature, documents, photo documentation, educational projects—site investigations that included a field visit, and interviews with key stakeholders involved in the projects. A total of nine in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the representatives from the municipalities in question, their tourist organizations, and the Republic Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage. Additionally, the information was also collected through photographic surveys during site investigations—four field visits per investigated site—and through the acquisition of maps, statistical data, and existing projects from the Municipality of Golubac, the City of Smederevo, and the Republic Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage.

In case studies, we have analyzed how the cultural resources of these fortresses and intangible heritage from their hinterland are used in cooperation with the University of Belgrade—Faculty of Architecture as a strategic instrument in educational projects with the purpose of creating effective place-branding strategies for the contemporary sustainable tourism development of the Middle and Lower Danube regions. The examples are given in the paper to present how the cooperation has taken place and the directions in which the future collaboration among universities, cultural heritage institutions, governmental and non-governmental organizations, local communities, and local authorities could continue. The paper highlights the significant results achieved by involving local communities in the processes of gathering experiences and requirements that are useful for the creation of place-branding strategies and projects to achieve the most efficient development of tourism in this area that respects the principles of safeguarding cultural heritage and thus sustainable development. By providing opportunities for the local community to actively participate in the formation of the planning strategies in the educational projects in question, one of the most important goals of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention [

2] has been fulfilled, which is to provide attention and responsiveness to the communities whose cultural traditions are being safeguarded. This is a so-called “bottom–up” participatory process [

46].

4. Discussion

The paper presents the potential of the Smederevo and Golubac fortresses’ heritage combined with the analyzed intangible cultural heritage to become instruments for the creation of effective place-branding tourism and planning strategies and urban design projects exercised through the educational projects.

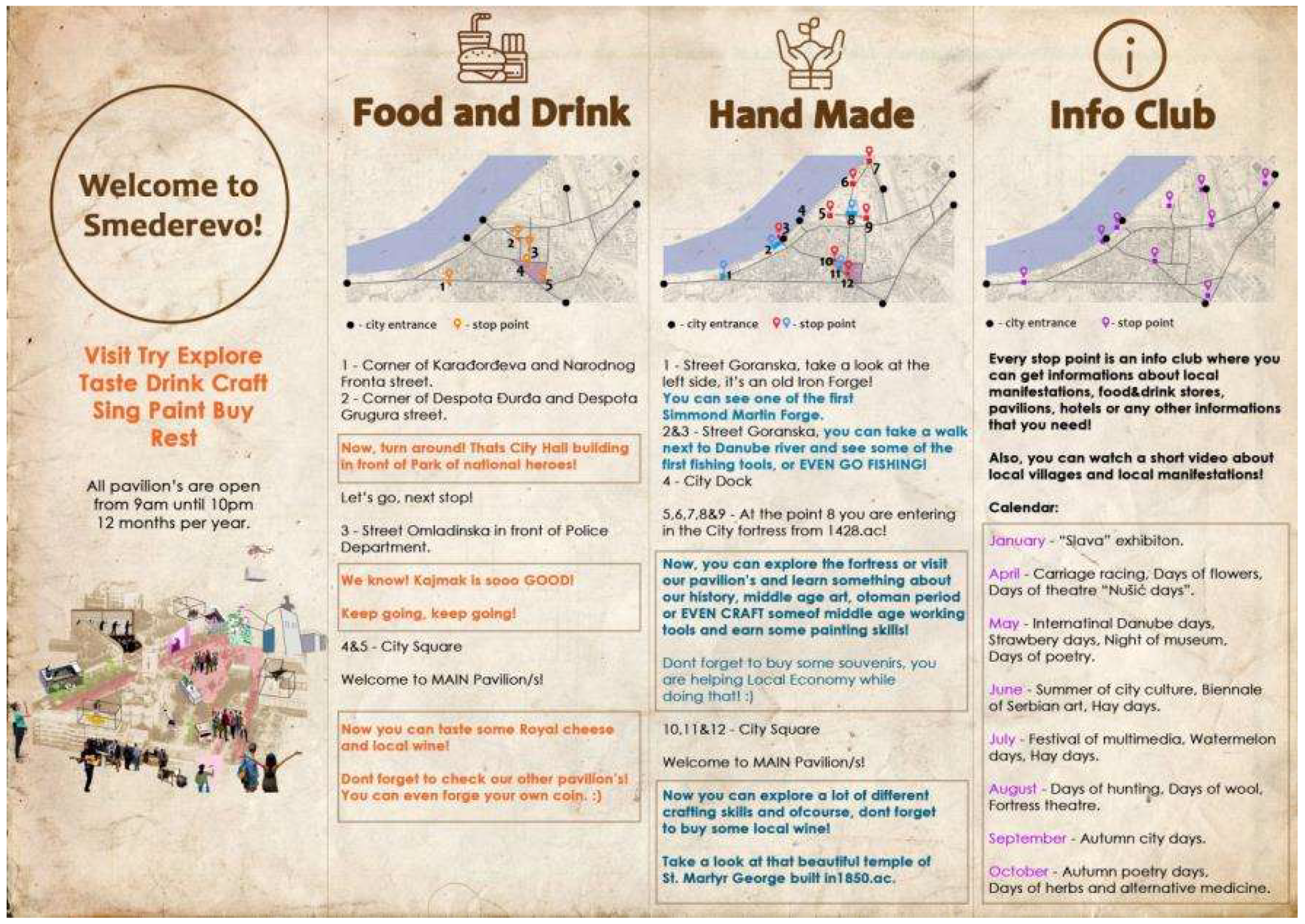

The educational projects have highlighted the collaboration, interdisciplinarity, and cooperation between the participants from academia, culture, tourism, the local government, and other branches of industry, and contributed to the introduction of innovative perspectives that offer multifaceted, accurate, and complete solutions. Cooperation between participants and stakeholders is not reduced to a linear communication process through which each participant seeks only to satisfy their interests. On the contrary, the aim is to improve common interests and achieve higher humanistic goals in terms of increasing the awareness of all participants about the problems under consideration. This implies that the potential flow of inclusive tourism takes place in the following way: presentation–consumption–acquirement of knowledge–preservation. What is achieved in this way, through this cycle of communication and collaboration among the participants, is a higher and more valuable, sustainable cycle of maintenance and revitalization of those elements of heritage that are often marginalized, yet its emphasis can attain far-reaching results.

Different dimensions of the sustainable treatment of fortresses and their surroundings in educational projects can be seen through the activation of their tourist potential in a way that enables the development of cultural tourism through the involvement of the local community and the development of social capital. Additionally, it can be observed through the fact that the overall tourist capacity does not jeopardize the values of cultural and historical heritage.

Table 1 provides an illustration of the relevant stakeholders’ engagement in the process of the projects’ conduction and the type of their inclusion in the place-branding process. Furthermore, it offers a review of the types of tangible and intangible heritage used, as well as the themes for the heritage interpretation, environmental aesthetics, and place-branding strategies employed during the process.

The whole process was primarily done in a participatory manner with the inclusion of stakeholders from different levels, depending on the specific topic considered and at various stages of the development process of the educational projects. In this way, the vertical and horizontal integration of interests through the initiation and development of possible partnerships for the realization of specific measures and small projects have been achieved. Participation was organized in several iterative cycles that reflected various levels of stakeholder participation through interactive workshops, round tables, discussions, and intersectoral thematic meetings. The interactivity of the participation process enabled the constant checking and redefining of identified problems, goals, and measures.

However, the need for the heritage protection on the one hand, and the need for the economic development of the same valuable assets, on the other hand, requires an integrated approach. Following the principles of sustainability, a holistic approach implies the simultaneous preservation of non-renewable resources, such as cultural heritage (the fortress in this case), and the enablement of its development with positive externalities to other sectors of sustainability, such as the economy, social cohesion, and ecology. Nevertheless, the entrepreneurial approach to regeneration, in general, has two potential challenges for the local context, heritage, and cultural identity. One is how to control globalization impact on a local level without neglecting local culture, but still securing competitive advantage. The second challenge is how to appropriately present the uniqueness and specificity of local cultural assets and still make them understandable to the contemporary world. Bearing those two challenges in mind, this approach has been reflected throughout the students’ proposals in educational projects in both the Smederevo and Golubac case studies and within the plan conduction in the Golubac case study.

The challenges mentioned above could be best tested through the confirmed examples of touristic and place-branding use of medieval cultural heritage, especially castles and fortresses, across Europe. Therefore, we provide here a brief comparison of the place-branding experience of fortress-linked heritage in Serbia and Italy to make it relevant for similar research and for situations of cultural heritage used for place branding and cultural tourism for theoreticians, practitioners, and community members going beyond merely educational projects.

A successful example of the place-branding experience of the interpretation and use of tangible and intangible heritage can be seen in the case of traditional rural buildings and Donnafugata Castle, located 20 km from the Ragusa city in southeastern Sicily in Italy. The castle itself has a significant historical and architectural reputation and hosts various social and cultural events and exhibitions that are important for tourists. The study researched and presented by Leanza, Porto, Sapienza, and Cascone [

68] shows an effective planning strategy for a tourist itinerary in rural areas for promoting cultural rural heritage and diversifying the tourism offer. The tourist itinerary—covering the area of about 51 km

2—combined the traditional rural buildings and enogastronomy with an already popular tourist attraction in Donnafugata Castle.

An essential aspect of the effective place-branding process was the implementation of the Interpretation Center in the Donnafugata Castle. In the center, tourists can acquire knowledge on the castle’s building materials and techniques, which were used as interpretive elements in the research study and the tourist itinerary [

68]. It was expected that if knowledge of the building materials and techniques—such as limestone, asphaltic stone, and wood—was disseminated among visitors, it might inspire tourists to learn more about the local community, their culture, and the building forms that are typical for the territory in question [

68]. Additionally, the information about the surrounding area and the map of the heritage interpretation-based itinerary with suggestions for the stopping points and the street network is available at the Interpretation Center.

Besides the Interpretation Center in the Donnafugata Castle, there are several other aspects used for the effective place-branding process and implementation of the heritage interpretation-based itinerary. The first is the bilingual didactic panel at the entrance of the castle, containing information about architectural details and building techniques, as well as the itinerary of the castle and traditional rural buildings in the area. The second is the didactic panel at the tourist route stopping points, containing rural architecture topics and information about different locations and themes, such as the enogastronomy—with wineries and museums exhibiting tools of the traditionally produced wine and oil; farms on which tourists can experience the production of local cheese, wine, and oil; the archeological areas; and the Baroque architecture of churches and palaces in nearby cities included in the UNESCO World Heritage list. The third is a mini-guide for the self-guided tours with the information about what could be experienced at specific stopping points. The fourth is the implementation of the geographical information system, which is used to store information about the tourist accommodation in the area near the castle, as well as traditional building materials and techniques, the road network, and traffic. The last aspect is the information and the map of connections within the area of the heritage interpretation-based itinerary [

68].

By comparing the place-branding experience of fortress-linked heritage in Serbia and Italy, we can observe that most of the specific elements of the interpretation and use of tangible and intangible heritage in the Italian case support and justify the approach in the Serbian cases of the Golubac and Smederevo fortresses. This stands for the proposed themes for heritage interpretation, as well as the tangible and intangible elements of cultural heritage used in the interpretation of places within educational projects. On the other hand, intangible aspects of the analyzed heritage themes’ interpretation are present in Serbia only in educational projects, while in the Italian case, they form a unique amalgam with tangible heritage.

Moreover, the possible future strategy and research for the development of tangible and intangible heritage could include different methods. Besides the analysis of European examples of successful instances of place-branding experience and the interpretation and use of tangible and intangible heritage, we can proceed with creating cultural routes along the Danube River. Routes are different historical ways that connect cultures, historical heritage, and events, highlighting the interdependence and symbiosis of intangible and tangible cultural heritage [

69]. Through cultural routes, we understand relationships, and share knowledge, values, ideas, and other multifaceted influences between people. The key point of cultural routes relates to communication. There may be many individual heritage elements when we consider cultural routes that are both intangible and tangible, such as fortifications, urban centers, archeological sites, architectural sites, places of significant historical events, cultural and natural landscapes, venues for performances, festivals and different events, etc.

By creating cultural routes along the Danube, which is already a natural route, different elements of cultural heritage could be incorporated with its tangible and intangible features, thus contributing to a more comprehensive approach of creative and sustainable cultural heritage tourism development in Serbia. In order to realize and promote new cultural routes, the efficient and joint cooperation of cultural institutions, municipal agencies, and regional agencies with participants from the tourism sector are required. The creation of these cultural routes as a primary condition requires an adequate relation between tangible and intangible cultural heritage, linking historical monuments, sites, and places with other intangible cultural resources such as the customs and habits of the people, traditions, rituals, religions, handicrafts, art crafts, music, dance, literature, social narratives, festivals, traditional markets, communities, beliefs, lifestyle, social identity, etc.

Creating cultural routes on the Danube along the Smederevo–Golubac path in the Lower Danube region can contribute to the creation of authentic experiences that enhance tourism in Serbia. Here are some potential examples of cultural routes in Serbia along the Danube: the cultural route Danube—Border and the Crossroads of Cultures, Paths of Medieval Serbia—surrounding the Danube and beyond, Ancient Roman Paths—covering the Danube and beyond, Paths of Buried Treasure of the Damned Jerina, Dragon Paths through Medieval Serbia, Sieges of the Golubac Fortress, and Construction of the Smederevo Fortress. The inclusion of the Smederevo and Golubac fortresses in the unique design of a thematic route along the Danube has the potential to attract foreign and domestic tourists and contribute to the development of place-branding strategies.

5. Conclusions

By introducing intangible cultural heritage into the focus of cultural tourism, the scope of stakeholders in tourism has expanded considerably. The focus of this approach was not only on the particular historical monument of the fortresses and the surrounding conservation area, but also on the much broader environment and stakeholders’ active involvement. This means that the ancient monument and its surroundings were interlinked with the social, economic, and spatial net, giving specific impetus to the urban development. In the formation of a place-branding strategy for touristic reuse of the Golubac and Smederevo fortresses, the following stakeholders were involved in the collaboration processes: the local community, individuals and indigenous people, the Ministry of Culture and Media of the Republic of Serbia, the Ministry of Trade, Tourism, and Telecommunications, the National Committee for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Republic of Serbia, the Ethnographic Museum in Belgrade, the Commission for the Inscription of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the National Register, regional coordinators responsible for central and eastern Serbia, touristic agencies, academic experts, scholars, museums, and other cultural institutions.

The presented case studies in this paper have demonstrated multiple benefits based on a multifaceted approach in solving everyday problems by providing synergy in outcomes that have been able to satisfy even the often-conflicted stakeholders. The ultimate product of this participatory collaboration, while respecting the legal framework and policies, emphasized the necessity of harmonizing the goals of cultural heritage safeguarding while satisfying tourism stakeholders, whose primary goal is to achieve as much profit as possible. The inclusive approach in practice has supported theoretical, social, and humanistic goals and served as a starting point for achieving the general goal of sustainability. Consequently, in order to achieve sustainable tourism development, profit must be limited and reduced to an adequate measure that does not violate the principles of cultural heritage protection.

In terms of governance and planning, the inclusion of different relevant individual local and national stakeholders and organizations, ranging from the various local government and public enterprises and agencies, as well as community members, including residents, in the whole educational and planning process had multiple objectives. In the first place, it was essential to gather a collection of official data firsthand. Then, it was necessary to gain understanding about their values, interests, and needs, and listen to their narratives to reveal specific tacit knowledge that they possess individually on the urban development issues in general and that relates to the culture, tourism, cultural identity and heritage in particular. Furthermore, it was equally important to gain the necessary confidence in personal contact with stakeholders and create strong bonds, and a feeling of mutual understanding and trust for future research steps.

The actual inclusion of stakeholders was done in accordance with the conditions described above, using numerous methods and levels of participation. Various participatory levels included informing, consulting, and occasionally even involving stakeholders who provided suggestions and critical remarks concerning specific students’ projects and expert studies. Several participatory methods have been used, such as open-ended questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, several individual meetings with residents and rural households in the wider territory of the Golubac and Smederevo municipality, workshops, and debates with city representatives, all in order to create a platform for establishing a dialogue among stakeholders and provide relevant feedback on the research and specific projects.

Nonetheless, as shown in the paper, while a great number of stakeholders with local knowledge and sense of the spirit of the place have been involved in the planning process, intangible aspects of the analyzed heritage cases are present in educational projects, and only partially present if it comes to the actual implementation and the physical reconstruction, as is the case with the Golubac Fortress. This clearly demonstrates that the focus on tangible aspects and the spatial interventions of place branding of cultural heritage is still dominant in practice in Serbia, despite the acknowledgment of economic and social aspects and the benefits of sustainability in the planning phase in educational projects.

Equally importantly, all of the proposed solutions in both analyzed cases to a greater or lesser extent indeed function as a kind of professional incentive in the attempt to link tangible and intangible heritage use for place branding and cultural tourism. The incentive is for local communities, stakeholders, experts from various fields, and public authority officials—and potentially, if realized, for future tourists. In this particular way, both the tangible and intangible heritage combined in educational projects have been interpreted and presented as a whole tourist and branded package rather than only as an individual element.

The overall research presented in this paper can be used as an informational, practical, and operational basis for further research of the integration of cultural heritage and tourism into practice. The study of the cultural heritage and place branding in educational projects ensures a better visibility of intangible and material cultural heritage. It also raises awareness of their mutual importance and the need of establishing a collaborative dialogue with all tourism stakeholders practicing inclusive forms of governance, while respecting the principles of cultural diversity and sustainability. We sincerely believe that the paper can be relevant for both theoreticians and practitioners bearing in mind the effects and possibilities that careful spatial and program interventions on cultural heritage in small and medium-sized cities can have on the community and sustainable development of its territory.