Illicit Chinese Small-Scale Mining in Ghana: Beyond Institutional Weakness?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. China’s Pursuit of Resources in Africa

3. Theorizing Institutions in Africa

[…] they are not the state, but they exercise public authority. They defy clear-cut distinction. In fact, as we venture to study the political contours of public authority and the political field in which it is exercised, we are saddled with a paradox. On the one hand, actors and institutions in this field are intensely preoccupied with the state and with the distinction between state and society, but on the other hand, their practices constantly befuddle these distinctions.[39] (p. 673)

The Constitution, Chieftaincy, and Land Deals in Ghana: Association or Dissociation?

4. Unpacking Customary Land Ownership and Chinese Small-Scale Mining in Ghana

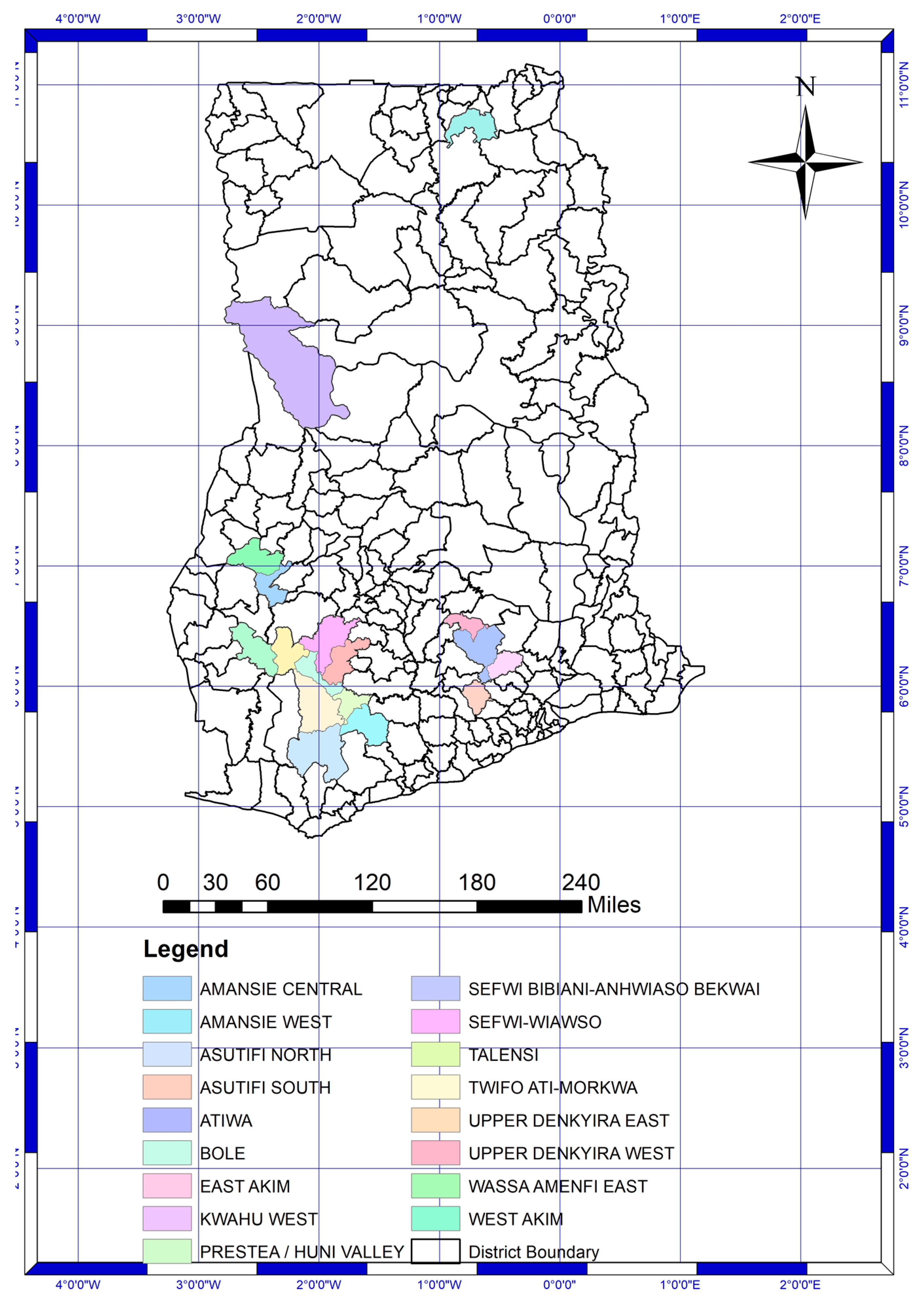

4.1. Acquisition of License and Persistent Illegalities

4.2. Chinese Involvement in illicit Small-Scale Mining: Implications and Community Resistance

4.3. State Response to Illegal Chinese Miners through Inter-Ministerial Task Force

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aryee, N.A.B.; Ntibery, K.B.; Atorkui, E. Trends in the small-scale mining of precious minerals in Ghana: A perspective on its environmental impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 11, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botchwey, G.; Crawford, G.; Loubere, N.; Lu, J. South-South Labour Migration and the Impact of the Informal China-Ghana Gold Rush 2008–13. UNU-WIDER 2018 Working Paper 2018/16. Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/south-south-labour-migration-and-impact-informal-china-ghana-gold-rush-2008–13 (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Crawford, G.; Botchwey, G. Conflict, collusion and corruption in small-scale gold mining: Chinese miners and the state in Ghana. Commonw. Comp. Politics 2017, 55, 444–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. Ghana Takes Action Against Illegal Chinese Miners. In Institute for Security Studies; ISS: Pretoria, South Africa, 2013; Available online: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/ghana-takes-action-against-illegal-chinese-miners (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Loubere, N. Chinese engagement in Africa: Fragmented power and Ghanaian gold. In China Story Yearbook 2018: Power; Golley, J., Jaivin, L., Farrelly, P.J., Strange, S., Eds.; ANU Press, The Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Minerals and Mining Policy of Ghana. Ensuring Mining Contributes to Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: https://www.extractiveshub.org/servefile/getFile/id/798 (accessed on 21 August 2019).

- Ahiadeke, C.; Quartey, P.; Bawakyillenuo, S.; Aidam, P. The Role of China and the U.S. In Managing Ghana’s Nonrenewable Natural Resources for Inclusive Development. In A Trilateral Dialogue on the United States, Africa and China; Conference Papers and Responses; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/All-Trade-Papers-2.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2019).

- Afriyie, K.; Ganle, K.J.; Adomako, A.A.J. The good in evil: A discourse analysis of the galamsey industry in Ghana. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2016, 44, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, S.; Aidoo, R. Beyond the rhetoric: Noninterference in China’s African policy. Afr. Asian Stud. 2010, 9, 356–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoo, R. The political economy of Galamsey and anti-Chinese sentiment in Ghana. Afr. Stud. Q. 2016, 16, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Armah, F.A.; Luginaah, I.N.; Taabazuing, J.; Odoi, J.O. Artisanal gold mining and surface water pollution in Ghana: Have the foreign invaders come to stay? Environ. Justice 2013, 6, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, I. Beyond Fuelling the Dragon: Locating African Agency in Africa-China Relations. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hilson, G.; Hilson, A.; Adu-Darko, E. Chinese participation in Ghana’s informal gold mining economy: Drivers, implications and clarifications. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 34, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; Potter, C. Structural Adjustment and Subsistence Industry: Artisanal Gold Mining in Ghana. Dev. Chang. 2005, 36, 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratton, M. Formal versus Informal Institutions in Africa. J. Democr. 2007, 18, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, N. Institutions and Democracy in Africa: How the Rules of the Game Shape Political Developments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, G. Disaggregating hybridity: Why hybrid institutions do not produce predictable experiences of peace. J. Peace Res. 2014, 51, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boege, V. The International-local Interface in Peacebuilding. In Exploring Peace Formation: Security and Justice in Post-Colonial States; Aning, K., Brown, M.A., Boege, V., Hunt, T.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 174–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, I. Impact of Sino-Africa Economic Relations on the Ghanaian Economy: The Case of Textiles. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2017, 3, 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah-Banin, A.A.; Tietaah, G.; Akrofi-Quarcoo, S. A Chink in the Charm? A Framing Analysis of Coverage of Chinese Aid in the Ghanaian Media. Afr. J. Stud. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, I.O.; Yeboah, T.; Boafo, J. Development for whom? Emerging donors and Africa’s future. Afr. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 4, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, S.T.; Recker, S. Understanding Sino-African Relations: Neocolonialism or a New Era? J. Int. Area Stud. 2013, 20, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nkrumah, K. The Class Struggle in Africa; Panaf Book Ltd.: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, P.S. Political Adjustment or Domestic Pressure: Democratic Politics and Political Choice in Africa. Third World Q. 1992, 13, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, V.; Butterfield, W.; Chen, C.; Pushak, N. Building Bridges; China’s Growing Role as Infrastructure Financier for Sub-Saharan Africa; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, D. Winner Take All: China’s Race for Resources and What It Means for the World, 1st ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Gold Council. Gold Demand Trends Full Year and Q4 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.gold.org/goldhub/research/gold-demand-trends/gold-demand-trends-full-year-2018 (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- World Gold Council. Gold Mine Production. 2019. Available online: https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/historical-mine-production (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Wenyu, S. China Consumed 1089 Tons of Gold in 2017, Tops World for Five Straight Years. 2018. Available online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2018/0202/c90000-9423181.html (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Xinhua. China Tops World’s Gold Consumers for 6th Year. 2019. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-01/31/c_137789866.htm (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Gonzalez-Vicente, R. China’s engagement in South America and Africa’s extractive sectors: New perspectives for resource curse theories. Pac. Rev. 2011, 24, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ghana Chamber of Mines. Performance of the Mining Industry in Ghana—2018. 2019. Available online: http://ghanachamberofmines.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Performance-of-the-Mining-Industry-2018.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- Botchwey, G.; Crawford, G. Lifting the Lid on Ghana’s Illegal Small-Scale Mining Problem. The Conversation. 25 September 2019. Available online: https://theconversation.com/lifting-the-lid-on-ghanas-illegal-small-scale-mining-problem-123292 (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- McQuilken, J.; Hilson, G. Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in Ghana; Evidence to Inform an ‘Action dialogue’; Research Report; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Voice of America. Exclusive—Gold Worth Billions Smuggled Out of Africa. 2019. Available online: https://www.voanews.com/africa/exclusive-gold-worth-billions-smuggled-out-africa (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Burrows, E.; Bird, L. Gold, Guns and China: Ghana’s Fight to End Galamsey. 2017. Available online: https://africanarguments.org/2017/05/30/gold-guns-and-china-ghanas-fight-to-end-galamsey/ (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Hausermann, H.; Ferring, D.; Atosona, B.; Mentz, G.; Amankwah, R.; Chang, A.; Hartfield, K.; Effah, E.; Asuamah, Y.G.; Mansell, C.; et al. Land-grabbing, land-use transformation and social differentiation: Deconstructing ‘‘small-scale” in Ghana’s recent gold rush. World Dev. 2018, 108, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabal, P.; Daloz, J.-P. Africa Works : Disorder as Political Instrument; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA; Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C. Twilight Institutions: An Introduction. Dev. Chang. 2006, 37, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajakaiye, O.; Ncube, M. Infrastructure and Economic Development in Africa: An Overview. J. Afr. Econ. 2010, 19 (Suppl.1), I3–I12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.E.E.; Lin, J.Y.Y.; Xu, L.C.C. Explaining Africa’s (Dis)advantage. World Dev. 2014, 63, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.H. Essays on the Political Economy of Rural Africa; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty; Profile: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bierschenk, T. States at Work in West Africa: Sedimentation, Fragmentation and Normative Double-Binds; Working Paper 113; Institut für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität: Mainz, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Luiz, J.; Stewart, M. Corruption, South African Multinational Enterprises and Institutions in Africa. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, J. The Theory and Politics of the Public/Private distinction. In Public and Private in Thought and Practice. Perspectives on a Grand; Weintraub, J., Kumar, K., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bayart, J.-F. The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly, 2nd ed.; Polity Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, R.A. Is power all there is? Michel Foucault and the “omnipresence” of power relations”. Philos. Today 1998, 42, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, S.M. Foucault’s View on Power Relations. Cogito 2010, 2, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J. Militarisation and State Institutions: ‘Professionals’ and ‘Soldiers’ inside the Zimbabwe Prison Service. J. South. Afr. Stud. 2013, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boege, V.; Brown, M.A.; Clements, K.P. Hybrid political orders, not fragile states. Peace Rev. 2009, 21, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagayoko, N.; Hutchful, E.; Luckham, R. Hybrid security governance in Africa: Rethinking the foundations of security, justice and legitimate public authority. Conflict Secur. Dev. 2016, 16, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bob-Milliar, G.M. Chieftaincy, Diaspora, and Development: The Institution of Nksuohene in Ghana. Afr. Aff. 2009, 108, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. 1992. Available online: http://www.ghana.gov.gh/images/documents/constitution_ghana.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2019).

- Boafo-Arthur, K. Chieftaincy in Ghana: Challenges and Prospects in the 21st Century. Afr. Asian Stud. 2003, 2, 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, C.; Sorens, J. Pre-colonial centralisation, traditional indirect rule, and state capacity in Africa. Commonw. Comp. Politics 2018, 56, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pul, H. Exclusion, Association, and Violence: Trends and Triggers of Ethnic Conflicts in Northern Ghana. Master’s Thesis, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aapengnuo, C.M. Power and Social Identity-The Crisis of Legitimacy of Traditional Rule in Northern Ghana and Ethnic Conflicts. Ph.D. Thesis, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fortes, M.; Evans-Pritchard, E.E. African Political Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Brukum, N.J.K. Ethnic Conflict in Northern Ghana, 1980–1999: An Appraisal. Trans. Hist. Soc. Ghana 2000, 4/5, 131–147. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41406661.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Minerals and Mining Act, 2006 Act 703. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=85445&p_country=GHA&p_classification=22.02 (accessed on 7 April 2019).

- Minerals and Mining (General) Regulations, 2012 (L.I. 2173). Available online: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/gha168926.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2018).

- The Guardian. Ghana Arrests 168 Chinese Nationals in Illegal Mining Crackdown. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/06/ghana-arrests-chinese-illegal-miners (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Asia by Africa. Galamsey in Ghana and China’s Illegal Gold Rush. Available online: https://www.asiabyafrica.com/point-a-to-a/galamsey-ghana-illegal-mining-china (accessed on 7 August 2019).

- Hausermann, H.; Ferring, D. Unpacking Land Grabs: Subjects, Performances and the State in Ghana’s ‘Small-scale’ Gold Mining Sector. Dev. Chang. 2018, 49, 1010–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Camp, E. Artisanal gold mining in Kejetia (Tongo, northern Ghana): A three-dimensional perspective. Third World Themat. A TWQ J. 2016, 1, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, G.; Agyeyomah, C.; Mba, A. Ghana—Big Man, Big Envelope, Finish: Chinese Corporate Exploitation in Small-Scale Mining. In Contested Extractivism, Society and the State: Development, Justice and Citizenship; Engels, B., Dietz, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulai, A. The Galamsey Menace in Ghana: A Political Problem Requiring Political Solutions? Policy Brief No.5; University of Ghana Business School: Accra, Ghana, June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C. Struggles for land and political power: On the politicization of land tenure and disputes in Niger. J. Legal Plur. Unoff. Law 1998, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ghana. Minerals and Mining Regulations (Compensation and Resettlement); L.I. 2175; Government of Ghana: Accra, Ghana, 2012.

- Hilson, G.; Potter, C. Why is Illegal Gold Mining Activity so Ubiquitous in Rural Ghana? Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Myxter, E. “Shanglin county clique’s” African Gold Rush: Get Rich or Die Trying (translation). The China Africa Project, 2013. Available online: http://www.chinaafricaproject.com/shanglin-county-cliques-african-gold-rush-making-a-fortune-ordie-trying-translation/ (accessed on 15 December 2018).

- Bach, S.J. Illegal Chinese Gold Mining in Amansie West, Ghana—An Assessment of its Impact and Implications. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, University of Agder, Grimstad, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aubynn, T.; Andoah, T.N.; Koney, S.; Natogmah, A.; Yennah, A.; Menkah-Premo, S.; Tsar, J. Mainstreaming Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining: A Background to Policy Advocacy, Draft Report; Ghana Chamber of Mines: Accra, Ghana, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Teschner, A.B. Small-scale mining in Ghana: The government and the Galamsey. Resour. Policy 2012, 37, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for Scientific and Industrial research (CSIR)—Water Research Institute. Impact of Small-Scale Mining on the Water Resources of the Pra River Basin; CSIR: Accra, Ghana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- News Ghana. Ministerial Task Force to Clamp Down On Illegal Mining. Available online: https://www.newsghana.com.gh/ministerial-task-force-to-clamp-down-on-illegal-mining/ (accessed on 3 April 2019).

- South China Morning Post. Ghana Arrest of Chinese Miners will not Harm Relations, Says Foreign Ministry. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1264081/ghana-arrest-chinese-miners-will-not-harm-relations-says-foreign-ministry (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Graphic Online. Anti-galamsey Task Force Resumes Operation Soon. Available online: https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/anti-galamsey-task-force-resumes-operation-soon.html (accessed on 11 April 2019).

- General News. In the wake of Ghana’s Crackdown on Illegal Chinese Miners-Chinese Diplomat Calls for New Era In Ghana-China Relations. Available online: https://www.modernghana.com/news/474761/in-the-wake-of-ghanas-crackdown-on-illegal-chinese-miners-.html (accessed on 3 April 2019).

- Quartey, K. Ghana’s Chinese Gold Rush. In Foreign Policy in Focus; FPIF: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Web. 1000 Illegal Miners Busted. Available online: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/1000-illegal-miners-busted-622033?fbclid=IwAR2Rvkkh-aUYgc-qc-FIsvpMjNCv0KRRNhW7k1kax7OjSzewq-aqfCWH_0o (accessed on 13 August 2019).

- Banchirigah, S.M. Challenges with eradicating illegal mining in Ghana: A perspective from the grassroots. Resour. Policy 2008, 33, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.D. Chinese Involvement in Illegal Small-Scale Mining in Namibia: An Assessment of its Impact and Implications. Master’s Thesis, The University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boafo, J.; Paalo, S.A.; Dotsey, S. Illicit Chinese Small-Scale Mining in Ghana: Beyond Institutional Weakness? Sustainability 2019, 11, 5943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215943

Boafo J, Paalo SA, Dotsey S. Illicit Chinese Small-Scale Mining in Ghana: Beyond Institutional Weakness? Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):5943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215943

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoafo, James, Sebastian Angzoorokuu Paalo, and Senyo Dotsey. 2019. "Illicit Chinese Small-Scale Mining in Ghana: Beyond Institutional Weakness?" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 5943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215943

APA StyleBoafo, J., Paalo, S. A., & Dotsey, S. (2019). Illicit Chinese Small-Scale Mining in Ghana: Beyond Institutional Weakness? Sustainability, 11(21), 5943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215943