Abstract

Drawing on the means–end chain method, this exploratory study attempts to provide a better understanding of consumers’ perceived risks towards eco-design packaging and its effects on consumers’ purchasing decisions. This study makes divers contributions in terms of theory, methodology, and policy making. Firstly, this study provides better comprehension for the concept of “eco-design packaging” by combining an industrial perspective (i.e., a life-cycle assessment: LCA) with a consumer perspective (i.e., consumer perceptions). The findings reveal the gap between consumers’ perceptions and the LCA results towards eco-design packaging. Secondly, this study offers an alternative perspective on consumers’ reactions towards eco-design packaging through exploring the “risks” instead of “benefits” examined to inspire package innovation. This study identified five perceived risks (functional, physical, financial, life-standard, and socio-environmental risks). Thirdly, this study illustrates the benefit of using the means–end chain analysis (MEC) framework to explore consumers’ reactions and purchasing behaviors towards sustainable products. Lastly, this study offers several actionable suggestions to managers, packaging designers, and policy makers.

1. Introduction

Packaging plays a major role in consumer purchasing decisions, since it links products to consumers through its technical and marketing functions [1]. Since the 1990s, incorporating the notion of sustainability into packaging innovation has been a crucial issue in marketing [2]. In response to this challenge, eco-design appears to be a strategic solution to optimize packaging [3] because an eco-design packaging is developed with concern for the environmental and/or its social impact in the various stages of its life cycle.

The previous studies focusing on consumers’ reactions towards eco-design packaging demonstrate that consumers react mainly positively towards this type of packaging [4]. The underlying assumption is that eco-design packaging attributes can be perceived positively by consumers. These studies aim to understand how consumers use the sustainability-related characteristics of packaging to give value to a product during purchasing decisions [4,5,6]. For instance, Magnier and Schoormans [7,8] show that eco-design packaging attributes (i.e., recyclable material and sustainable cues) have a positive effect on the perceived quality and sustainability of the product [9], the perceived ethicality of brand, and purchasing intention [7].

However, despite consumers’ positive attitudes, they do not generally purchase the eco-packed product, which is instead characterized by a low purchase rate [2,10,11,12,13]. This phenomenon of the discrepancy between attitudes and effective purchasing behavior is defined as the attitude–behavior gap [14,15,16,17].

A potential explanation for the attitude–behavior gap is that even though eco-design packaging is developed to reduce negative environmental and/or social impacts, it is not consistently perceived positively by consumers. Packaging itself is often poorly understood by consumers who may perceive it as an unnecessary “source of pollution”. A survey conducted for Eco Entreprises Quebec indicates that barely over one fourth of consumers believe that packaging is necessary to protect and transport products. The negative environmental impact of packaging is greatly overestimated, as packaging accounts for under 10% of the environmental impact of the products it protects; only 12.6% of consumers know this, however [18,19].

Hence, it is necessary to shift from the consumers’ positive reactions (i.e., perceived benefit) to their negative reactions (i.e., perceived risk) associated with eco-design packaging to better explain the attitude–behavior gap and, in turn, to gain a complete understanding of consumer behavior towards eco-design packaging.

Perceived risk is defined as “the subjective anticipation by consumers of conceivable losses when assessing alternative choices” [20] (p. 193). In consumer responsible behavior literature, perceived risk refers to the barriers to the consumption of a sustainable product (e.g., price, quality, and time) [2,10,11,21]. Moreover, perceived risk is viewed as a crucial determinant to understand the consumer decision-making process for sustainable products, in particular, the attitude–behavior gap, because it links concrete product attributes (the “means”) to underlying values (the “end” that the consumer expects by purchasing a particular product such as an eco-design packed product) [20].

Therefore, this study aims to explore the negative aspects (i.e., consumers’ perceived risks) associated with eco-design packaging and its effects on consumer purchasing intention. Drawing on means–end chain (MEC) analysis [22,23], this study attempts to answer four questions: (1) How do consumers perceive eco-design packaging (i.e., is there a gap between consumers’ perceptions and industrial definition based on life-cycle assessment (LCA)? (2) What are the consumers’ perceived risks associated with eco-design packaging in their purchasing decision processes? (3) How can consumer segmentation be carried out in terms of the consumers’ perceived risks concerning eco-design packaging? (4) What are the potential eco-packed product consumption patterns based on these perceived risks?

MEC analysis is an efficient approach to determine the consumer purchasing decision process for a specific product. According to Gutman [24], all consumer behaviors have consequences (positive or negative), which increase by consuming products (including divers attributes). Consumers tend to choose the product that generates the most positive consequences and minimize the negative consequences to achieve their desired lifestyle state (i.e., an individual value). Hence, MEC analysis is appropriate for answering research questions. This approach not only identified the determinants (i.e., the eco-design packaging attributes, consequences, and individual values) that characterize the most important factors for consumers to purchase eco-packed products but have also been able to provide a meaningful association between them [22]. The consumers use this entire attribute-consequence-value structure to assess their individual value (the ends). The achievement of the goal depends on the attributes of the product (e.g., its packaging, brand, and quality), which is considered to be the means. Previous studies show that individual values influence consumer preferences for product attributes. For instance, a consumer with pro-environmental values will give priority to the sustainable attributes of packaging: Recyclable or biodegradable materials [25,26], package downsizing [27], environmental claims, and labeling [28]. Moreover, numerous studies indicate that pro-environmental behavior could be influenced by internal determinants such as individual values, attitudes, emotion, motivation, and knowledge [29,30]. In particular, pro-environmental values (e.g., feelings of being responsible and universalism) and attitudes (e.g., attitudes towards wastage and recycling) have positive impacts on pro-environmental behavior. For instance, Cox et al. [31] and Graham-Rowe et al. [32] reveal that attitudes towards food waste and universalism values influence a consumer’s intention to reduce food waste. A consumer with positive attitudes towards recycling and the environment has a greater intention to recycle packaging [30] and carries out overall recycling behaviors [33,34,35,36]. Likewise, a consumer with a high level of environmental awareness has more positive perceptions towards eco-packed food [9].

This study makes the following contributions. From a theoretical perspective, (1) this study offers a better understanding of the concept of eco-design packaging by combining an industrial perspective (i.e., LCA) with a consumer perspective. The findings reveal the gap between consumer perception and the LCA results toward eco-design packaging. (2) We provide an alternative perspective on consumers’ reactions towards eco-design packaging through exploring the five perceived risks (i.e., functional risks, physical risks, financial risks, life-standard risks, and socio-environmental risks) in their cognitive chaining. Methodologically, this study provides an alternative approach—MEC—to investigate consumers’ reactions towards eco-design packaging and other consumers’ decision-making processes [22,23]. From a policy perceptive, the finding can be helpful to improve eco-design packaging dissemination and environmental policies including: (1) integrating consumer perspectives into packaging innovation, (2) improving eco-design packaging labeling systems, and (3) integrating eco-design packaging into the economy’s circular framework.

The paper begins with a review of the existing literature dealing with three key concepts: Eco-design packaging, perceived risk, and value. Then, the paper describes the conceptual framework, research method, and key findings. Subsequently, the theoretical, methodological, managerial, and political implications are discussed. The paper concludes with the limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Eco-Design Packaging

Given the current growing public awareness and concern for the environment, eco-design is viewed as a feasible option for packaging optimization by integrating environmental impact concerns [3]. Pauer, Wohner, Heinrich and Tacker [25], Schiesser [37] argue that eco-design incorporates environmental and/or social concerns into packaging through life-cycle assessment in order to attain eco-efficiency. A number of key criteria need to be met in the life cycle of packaging [38]:

- Design: All the stakeholders of the conceptualization of packaging (design, packaging industry, supply, logistics, research and development, and marketing) are taken into consideration from the beginning, to enable a comprehensive vision of the issues involved.

- Procurement: Eco-friendly materials are used (easy to disassemble, recyclable, and degradable).

- Manufacturing: The whole packaging system is optimized: Primary packaging (encouraging the end users/consumers), secondary packaging (filling the displays at points of sale), and tertiary packaging (facilitating the transport of a number of products).

- Consumption or usage: Consumer expectations are integrated: The convenience of use (rate of a refund, rate of opening/closing), the visualized information (brand name, country of manufacture, etc.), and the volume and the weight.

- End-of-life: The components of packaging should be easy to disassemble, recyclable, and degradable.

2.2. Effects of Packaging on Purchasing Decisions

Packaging is commonly examined in terms of two marketing research perspectives. The first view corresponds to a holistic or overall perspective, where packaging’s effects cannot be identified separately from the products. The other view is an analytical perspective, where packaging is viewed as a product-independent component. The concept of packaging is thus broadened through the multi-attribute theory that views packaging as a combination of various attributes. Smith [39] argues that there are four main attributes of packaging: Shape, size, color, and graphics. Other researchers have focused on size, shape, material, color, text, and the brand [40]. There is no consensus on the classification of packaging attributes. Underwood [41] identifies two categories of attributes: Visual attributes (color, photography, image, and logo) and structural attributes (materials, shape, and weight). Magnier and Schoormans [7] investigate the communicative function of packaging and use the typology of Rettie and Brewer [42], who classify attributes into visual attributes (appearance and image) and verbal attributes (color, photography, image, and logo).

The effects of packaging on consumers have been extensively examined. Most studies focus on the influence of visual attributes, such as color [43,44], size [45,46], and packaging shape [44,47,48,49]. These elements are viewed as non-verbal attributes that carry product and brand meanings [50]. Other studies have examined the impacts of a combination of several attributes. Pantin-Sohier [44] investigated the mechanisms whereby a combination of color and shape influences consumers’ perceptions of brand personality. A combination of size and shape is shown to influence consumers’ perceptions of volume and consumption quantity [48,49]. Magnier and Schoormans [7,8] have investigated the impacts of the ecological aspects of packaging on consumers’ attitudes. Their findings show that consumers’ attitudes towards eco-design packaging varies depending upon its perceived value, which results from a cost–benefit trade-off. The study, however, does not explain the source and nature of the gap between people’s positive attitudes towards eco-design packaging and their contradictory purchasing behaviors, characterized by a low purchase rate. The social desirability bias and the perceived risks of responsible consumption appear to be two factors accounting for the gap between attitudes and behaviors [51,52,53].

2.3. Perceived Risk

Volle [54] views perceived risk as the subjective uncertainty people perceive towards the potential losses relating to the attributes that determine product (goods or service) selection in a given purchase or consumption situation. Losses are to be understood as a result that is inferior to a subjective reference point that is not necessarily zero, nor the status quo, but possibly the level reached through the best alternative or any other individual–specific reference [39,45,46,55,56].

Perceived risk is usually defined as a multidimensional concept. Kaplan et al. [57] identify five dimensions of perceived risk: Functional, financial, physical, psychological, and social. An investigation of perceived risk is one of the key research topics in the domain of consumer behavior. The concept is usually seen as carrying a negative value, something that indicates why consumers decide not to select a given product [58]. It is also used as a tool for market segmentation, product and packaging improvement, pricing, distribution channels, and communication strategies [59]. The attributes of a product, including its packaging, constitute one of the main antecedents of the perceived risk of consumers’ purchasing decision-making [58].

Furthermore, in the field of responsible consumption research, several studies show that perceived risk, particularly in its functional and financial dimensions, is viewed as a main deterrent to the consumption of ecological products. This could explain the significant gap between declared purchase intention and actual purchasing behavior for socially responsible product consumption (i.e., the Green Gap) [20].

2.4. Value in the Purchasing Decision Process

Incentives and deterrents are viewed as the two main factors accounting for consumer selection or inclination, while people’s values are the greatest incentives for consumer behavior [22,60]. According to Valette-Florence [55], value involves the interaction of three levels: Their entire set of individual values and personality traits, their set of attitudes and activities, and the products purchased. People whose lifestyles are similar (i.e., those who share similar behavior patterns for each of the three levels) form a homogeneous group. In other words, people’s lifestyles derive from their value systems, attitudes, and consumption patterns [55]. Hence, individual values facilitate our understanding of the incentives and deterrents that govern people’s attitudes, preferences, and behaviors towards products [56,60]. The present study is based on the value system proposed by Kahle and Kennedy [56], which includes a sense of belonging, the need for excitement, fun and enjoyment, warm relationships with others, self-fulfillment, being well respected, safety, and self-respect; this system has considerable predictive power over consumer behaviors [55].

3. Conceptual Framework: The Means–End Chain Theory

To reveal people’s incentives or deterrents and behavioral patterns, Young and Feigin [61] introduced the means–end chain (or cognitive chaining), further developed by Gutman [62] and Reynolds and Gutman [22]. According to Young and Feigin [61], consumers often take into consideration product attributes that represent benefits. The set of associations derived from these benefits and consequences is reflected in increasingly abstract and significant values that form cognitive chaining [23]. Cognitive chaining can arise from the connection between a product’s attributes, the consequences consumers derive from those attributes, and potential links with consumers’ values [23].

In order to describe the purchasing decision process for a specific product, cognitive chaining links three successive levels of abstraction: Attributes, consequences, and values [22,23]. Olson and Reynolds [63] fine-tuned the structure of cognitive chaining by adding two intermediate levels, for a total of five levels: Concrete attributes, abstract attributes, functional consequences, socio-psychological consequences, and values. Next, Valette-Florence [23] advocated a six-level cognitive chain: Concrete attributes, abstract attributes, functional consequences, socio-psychological consequences, instrumental values, and final values. The author argues that this six-level classification can more effectively delineate the boundaries between product knowledge and self-knowledge, hence enabling an increased understanding of people’s selection processes. It is worth noting that in some cases, it is easier to use negative reasons to justify choices, since negative associations also reflect people’s preferred options [64].

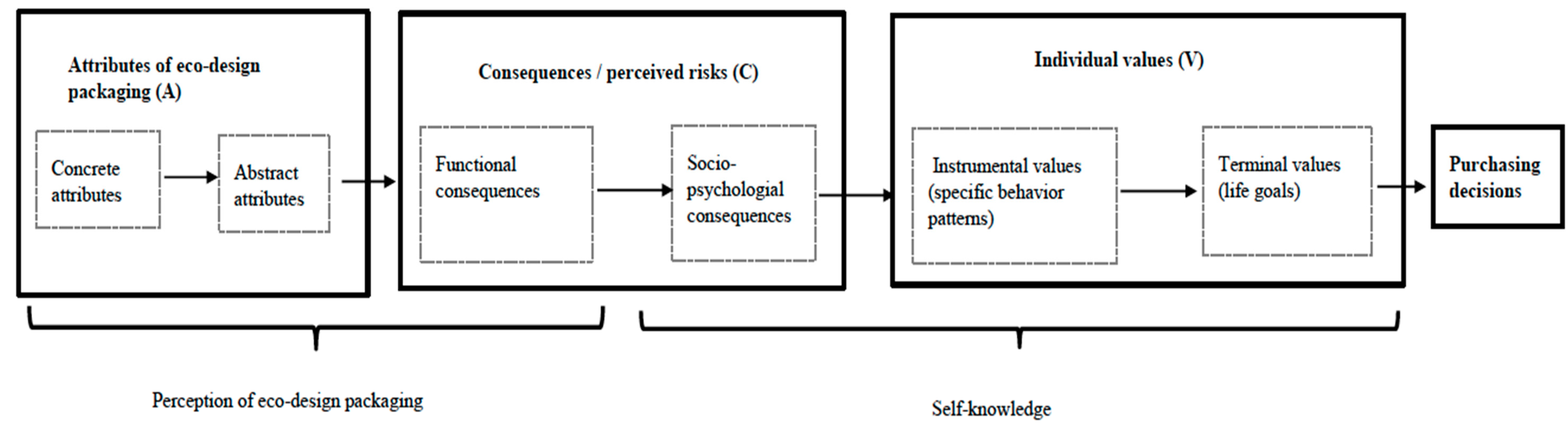

This study is based on the theoretical framework of the means–end chain, with the intent to understand consumers’ perceived risks towards eco-design packaging and the role of consumers in the purchasing decision process of eco-packaged products. Figure 1 shows this conceptual framework. Three main components from the cognitive chain are related to eco-design packaging: The attributes of the eco-design packaging (A’s), the perceived risks or consequences (C’s) generated by the attributes, and the individual values related to the consumption of eco-packaged products (V’s).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. Source: Adapted from Valette-Florence, Ferrandi, and Roehrich [65], Figure 2 (p. 34).

The attributes are classified into two categories: Concrete attributes involving the essential characteristics needed to describe and assess packaging (e.g., recyclable or recycled materials, shape, and color), and abstract attributes representing the subjective assessment characteristics. Consumers’ personal interpretations determine their appraisal of abstract attributes, such as price or brand image [65].

Similarly, there are two levels of consequences: Functional consequences, produced by the use of packaging (e.g., product preservation and shelf life) and socio–psychological consequences, which are related to the social functions of eco-design packaging (e.g., an image of environmental protection). In this study, we focus on the negative consequences or risks.

Finally, the individual value systems are divided into two hierarchies [66]. Terminal values (in other words, life goals (i.e., the ends)); relationship to individual or social goals, such as price or freedom; instrumental values; or behavioral patterns (i.e., the means) are defined as ways of being or doing [65].

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

In order to meet our research goals, we used an analysis of cognitive chaining, as this approach reveals consumers’ cognitive structures [67]. These structures involve the relations between the product attributes (A), the derived consequences for consumers (C), and the consumers’ individual values (V). In this study, we focus on perceived risks that, just like values, represent the antecedents of eco-responsible purchasing behaviors [68]. An analysis of cognitive chaining also reveals the boundary between knowledge or perception of more concrete attributes and abstract individual values [23,60]. This cross-cutting approach (attributes, consequences, and values) brings to light the structure of the individual cognitive chaining of consumers’ perceived risks and increases our understanding of the chaining representative of consumers’ decision-making processes when purchasing eco-packaged products.

The analysis of consumers’ cognitive chaining was conducted through three successive steps [23] (Please see Table 1, Methodology).

Table 1.

Methodology.

Step 1. Generating the relevant attributes, consequences, and values associated with eco-design packaging based on six levels of cognitive chaining: Concrete attributes, abstract attributes, functional consequences, socio-psychological consequences, instrumental values, and terminal values. In this first step, data were collected using two techniques: Documents analysis and a focus group. The objective is to (1) explore consumers’ perceptions of eco-design packaging attributes (to answer research question 1); (2) to examine the perceived risks associated with eco-design packaging (to answer research question 2).

First, the attributes of different types of eco-packaging were identified and defined through a rigorous analysis of the academic [1,4,69,70,71] and professional literature [72] related to packaging, eco-design, consequences, and individual values [56,73]. The goal of this stage is to generate an initial list of A-V-Cs from the existing literature.

Then, a focus group of eight consumers or people responsible for their household consumption was formed. The heterogeneity of the demographic characteristics of the people involved was ensured to explore the attributes, consequences, and individual values of consumers underlying the decision-making processes associated with eco-design packaging (Please see Appendix A Table A1, Sample of the focus group). This step also attempted to complement the list of A-C-V’s created in the last step from a consumer perspective. A focus group is more appropriate than individual interviews because group dynamics and flexibility can yield greater insight into an innovative concept (i.e., eco-design packaging) [74]. More precisely, the process was carried out around three topics: (1) general perceptions toward eco-design packaging attributes; (2) the consequences related to the consumption of eco-design packaging (e.g., previous experiences or protentional consequences); and (3) consumers’ evaluation criteria in their purchasing decisions (Please see Appendix B, Guide of the focus group).

Step 2. Constructing the individual cognitive chains associated with eco-design packaging to segment consumers based on their perceived risks of eco-design packaging (to answer research question 3).

The data were collected through 19 face-to-face individual laddering interviews, lasting about 25 min each [75], with pre-coded cards based on a list of A-C-V’s and several blank cards. The respondents were selected because they were responsible for their household consumption and thus had experience and ideas regarding eco-design packaging (Please see Appendix C Table A3, Sample of individual interviews). An interview with cards was more appropriate than a traditional individual interview since pre-coded cards can improve the efficiency and objectivity of the results [23]. A water bottle that was redesigned according to the LCA was chosen as an exemplar of eco-design packaging. The results of the focus group showed that the eco-design packaging was an improvement (i.e., using the same quantity of 100% recycled rPET plastic contains more water) and was the most visible by consumers.

The interviews were performed as follows. The participants were presented with cards, each related to eco-design packaging attributes. They were first asked to form three groups of attributes with a rank of importance (most important, average, not important). Then, they were asked to select the most important attributes of the first group (i.e., the most important group). The same procedures were repeated at the level of consequence according to the most important attributes identified in the last step, and so on until the values were level. This was done to create a meaningful link between attributes-consequences-values.

Step 3. Constructing an aggregated hierarchical map in order to explore the potential eco-packed product consumption patterns based on perceived risks. This step seeks to explore potential eco-packed product consumption patterns based on perceived risks (to answer research question 4).

4.2. Data Analysis

Three approaches were used to analyze the interview data: (1) Content analysis—three coding levels were used to gauge consumers’ perceptions towards the attributes and risks related to eco-design packaging: In vivo coding, based on the concepts emerging from the focus group and the literature; axial coding, based on an analysis of the relationship between the first-level concepts; and an aggregated dimension [76,77,78]. (2) A non-linear canonical correlation analysis of the hierarchical taxonomy was performed with SPSS Statistics version 23.0 [79] to identify the principal A-C-V orientations. (3) An analysis of the consumers’ hierarchical maps was used to build an aggregated picture of the set of individual chains.

The content analysis of the focus group session and of the literature yielded maps of the attributes, consequences, and values for the individual interviews. Table 2 shows 23 attributes, 17 consequences, and 13 values that were identified.

Table 2.

List of attributes, consequences, and values associated with eco-design packaging.

5. Results

5.1. Perceptions of Eco-Design Packaging

From an analytical perspective, packaging is viewed as a combination of various attributes [43,44]. However, the results of the focus group show that there is a considerable difference between the definition of an eco-design packaging found in the literature and consumers’ perceptions of it.

From the consumers’ point of view, the attributes of an eco-design packaging appear to be a condensed version of those found in the literature. If we compare and contrast the attributes that emerged in the discussion group and those found in the literature [18,72], a number of issues are brought to light (Please see Table 3).

Table 3.

Industry view versus consumer view of eco-design packaging.

- Some attributes are common to both perspectives:

- The packaging is made from recyclable materials or materials that are more environmentally friendly.

- The weight of the packaging ought to be lighter.

- The size is optimized (i.e., the content/container ratio is improved).

- The packaging’s color is green, blue, or transparent.

- The packaging shows an eco-label or other environmental label.

- Other attributes appeared in the consumers’ lists because of their lack of knowledge of some new concepts:

- From the consumers’ perspective, environmentally friendly materials comprise materials such as cardboard, paper, recycled plastic, and biodegradable materials.

- An optimized size and structure are incorporated into the optimization process, the content/container (product/packaging) ratio (such as an improved closing system), and the weight and/or volume optimization of the packaging components/elements.

- Some abstract attributes (i.e., attributes not necessary to describe the physical characteristics of eco-design packaging), such as the high price of eco-packaged products relative to the price of products in conventional packaging or brand images appearing to be significant to consumers.

Overall, the list of attributes for eco-design packaging, as perceived by consumers is more limited than that found in the literature [1,4,69,70,71], contains more generic characteristics, and includes some abstract or non-observable attributes.

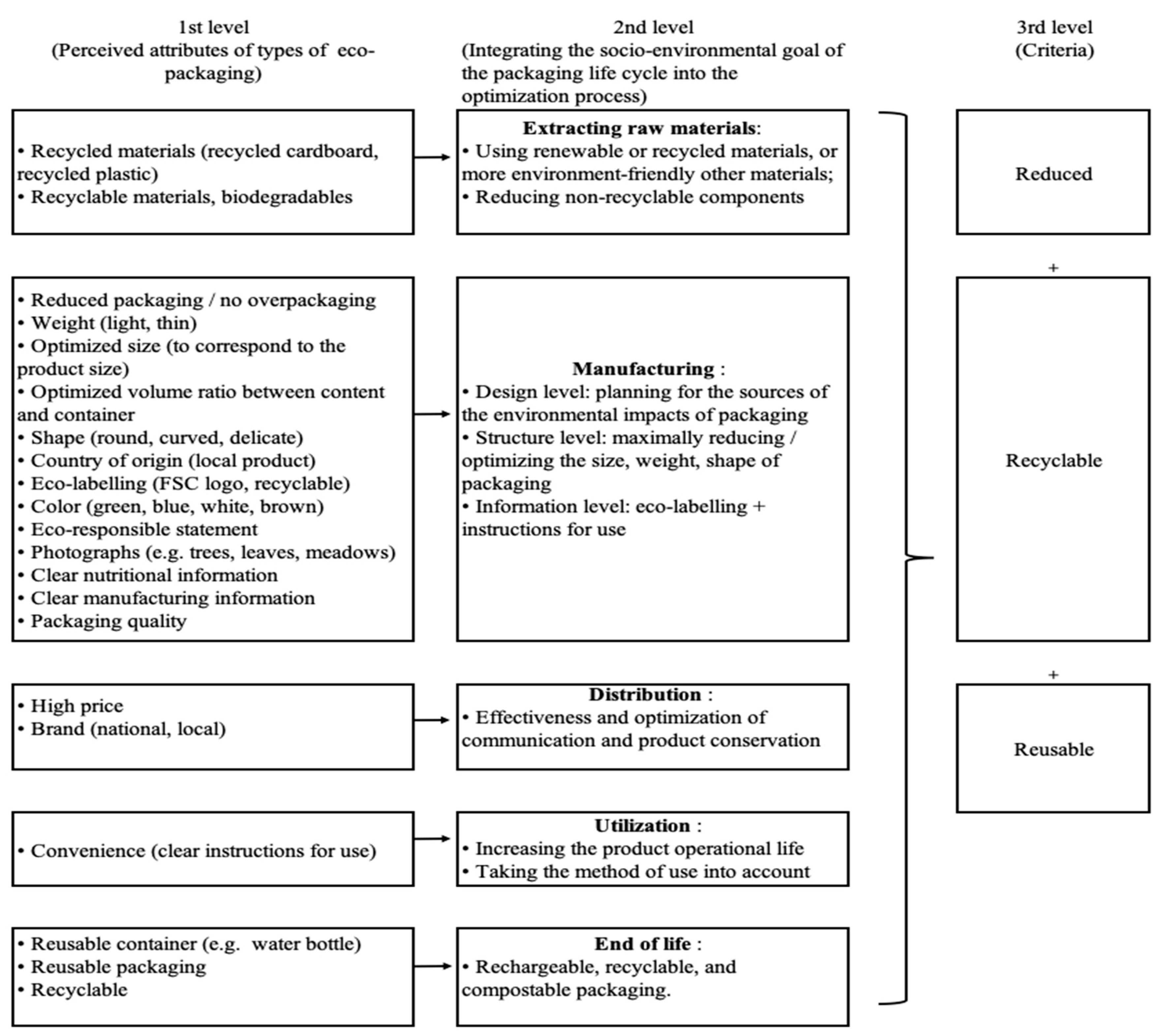

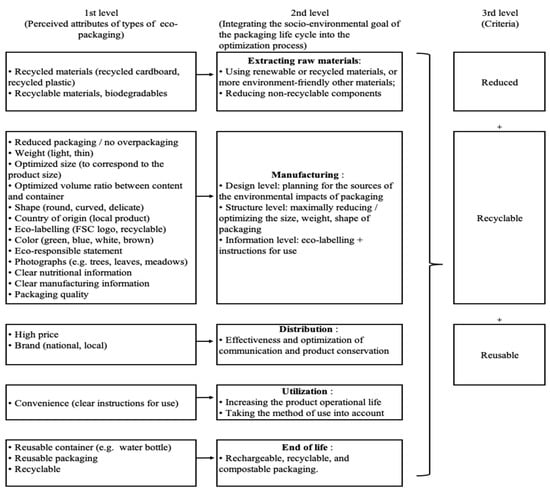

Figure 2 shows the three hierarchical levels of the data related to consumers’ perceptions of eco-design packaging. The first level includes those key attributes that emerged from the discussion group and those identified from the literature on eco-design packaging.

Figure 2.

Consumers’ perceptions of eco-design packaging.

The second level incorporates the major characteristics of eco-design packaging during its lifecycle. During the extraction of raw materials consumers perceive that eco-design packaging is made with renewable or recycled materials; at the stage of manufacturing, consumers focus on optimization in terms of a reduced structure and via communication (especially eco-labeling); then, at the stages of distribution and use, consumers expect the packaging to protect and preserve products more effectively. At the end of its life cycle, the packaging is expected to be rechargeable, recyclable, and biodegradable.

The last level comprises three interrelated dimensions of eco-design packaging, the three Rs: Reduction (“Before, I used to buy large packs (...) now, I buy in smaller quantities”), reuse (“I prefer cardboard packaging to plastic one (...) I often buy glass bottles because I know that I can reuse them, for example, the Mason jars, we use those”), and recyclability (“If it’s not recyclable, I always hesitate before buying; we don’t know what to do with our waste, and even if they sort some of it, they also bury a lot”).

5.2. Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging

Table 4 shows that eight consequences or functional risks and three psycho-sociological risks were identified in the group discussion and the interviews. Functional risks involve notions such as value for money, the effectiveness of product protection and preservation, waste (especially food waste), potential health risks, and esthetic aspects. The main factors related to psycho–sociological risks involve a certain distrust towards marketing strategies focused on environmental protection and the fear of changing one’s habits.

Table 4.

Perceived risks associated with eco-design packaging.

5.3. Major Orientations and Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging

Before identifying the major orientations of consumers towards eco-design packaging, it is necessary to establish which attributes, consequences, and values are the ones most often mentioned (i.e., frequency of citations) by consumers, to determine the underlying mechanisms of the decision-making process. The frequency of citations represents consumers’ sensitivities to the product under investigation [60]. The study participants are more sensitive to “high price” (n = 13), “recyclable materials” (n = 11), “eco-labeling” (n = 11), “packaging quality” (n = 9), and “shape” (n = 9).

We also observed that consumers express doubts regarding eco-design packaging because of its “value for money” (n = 17), “health safety” (n = 15), “aesthetic sacrifice” (n = 12), “sacrifice of hygiene/cleanliness sacrifice” (n = 15), and “protection effectiveness” (n = 10).

Values no longer mentioned include “inner harmony for personal well-being” (n = 16), “happiness” (n = 14), “enjoyment and excitement” (n = 13), and “family security” (n = 13).

The non-linear canonical correlation analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics version 23 [79]; this analysis identified a perceptual space taking into account the entire set of cognitive chains. The purpose of this stage was to establish a typology of cognitive chains. Table 5 shows the three variables of the chain (i.e., the A-C-Vs) and the indices of impairment and adjustment in the perceptual space. (Impairment index: The difference between the maximum adjustment and the actual adjustment. The lower the impairment index, the greater the coherence.)

Table 5.

Impairment index by set of variables and orientations.

We observed that the impairment index for the three variables (A-C-Vs) are generally low, which indicates high chain consistency for each variable (A-C-Vs). The apparent variable-consequences is among the best variable distinguishing the three cognitive chain orientations compared with the attributes and values, because variable-consequences has the lowest impairment index (0.132). The non-linear canonical correlation analysis also identified the most discriminating items for each variable (A-C-Vs) that distinguished one orientation from another (Please see Appendix D Table A4).

Ward’s method was used to create a hierarchical taxonomy based on three variables (A-C-Vs) in order to segment consumers. The variable-consequences was used to describe each segment since it was the discriminating variable (compared with the two other variables, attributes and values) that distinguished between the three orientations (index = 0.132). This analysis revealed three groups of consumers. Each group evinces its own structure of (A-C-Vs) towards eco-design packaging (Please see Table 6).

Table 6.

Consumer segments according to perceived risks (The term “consequence” only refers to second a level variable (A-C-V’s). It is measured by 17 items. However, the term “risks” refers to the aggregated concept from the findings. It describes the consumer segments (Table 6) and their risk-oriented consumption patterns (Figure 3)).

- Segment 1—Eco-conscious consumers: The first segment includes consumers highly concerned by the socio-environmental risks of eco-design packaging (i.e., food waste, trust towards the product and the brand, practicality, respect for the environment). More precisely, two attributes of eco-design packaging distinguish Segment 1 from another: Recycled materials, reduce packaging/no overpackaging.

- Segment 2—Utilitarian-minded consumers: The second segment views as significant financial and functional risks of eco-design packaging. These consumers take value for money into account; they tend to find a compromise between the key packaging functions, the product price and life standard.

- Segment 3—Skeptical consumers: Segment 3 consumers are skeptics. They stress the communication function of eco-design packaging and link it with the protection function of packaging.

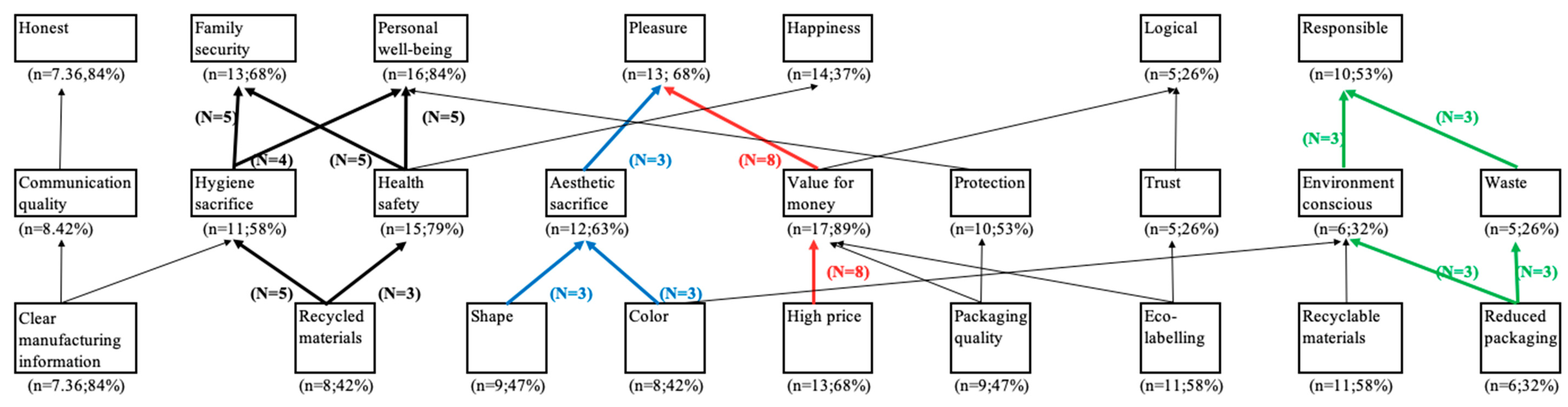

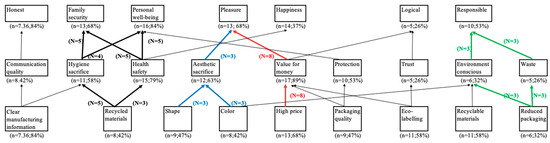

Through an analysis of the frequency of the associations between the concept pairing (attributes, consequences, values), an aggregated hierarchical map was generated to explore the potential eco-packed product consumption patterns based on the perceived risks associated with eco-design packaging.

5.4. Impacts of the Perceived Risks towards Eco-design Packaging in the Decision-Making Process

The citation frequency shows that consumers appear to be sensitive towards a number of attributes of eco-design packaging, such as “recyclable materials” (58%), “high price” (68%), “shape” (47%), “recycled materials” (42%), “reduced packaging” (32%), “color” (42%), “eco-labeling” (58%), and “packaging quality” (47%). The risks most frequently perceived are “communication quality” (42%), “respect for the environment” (32%), “value for money” (89%), “hygiene sacrifice” (58%), “health sacrifice” (79%), “aesthetic sacrifice” (63%), “food waste” (26%), “product protection effectiveness” (53%), and “trust” (26%). This analysis of item frequency highlights the different types of perceived risks towards eco-design packaging. “Value for money”, “health sacrifice”, “aesthetic sacrifice”, “hygiene sacrifice”, and “protection effectiveness” are the determining factors in the purchasing decision process for eco-packaged food products, with respective scores of 89%, 79%, 63%, 58%, and 53%. These risks, however, represent only two thirds of the cognitive chain. A representation of cognitive chaining by means of a hierarchical map (Please see Figure 3) shows the consumers’ cognitive networks towards eco-packaged products.

Figure 3.

Aggregated hierarchical map of risk-oriented consumption patterns.

Figure 3 shows an aggregated hierarchical map of the consumers’ risk-oriented consumption patterns towards eco-packaged products. All the direct associations between concept pairing (attributes, consequences, and values) that are superior to two are shown in this figure to display the chains. The cutoff value should be superior to or equal to 5% of the sample size [64]. The major consumption patterns are shown by the higher numbers of citations of direct and indirect relations, shown with bold arrows. Two association types are evident: Direct and indirect. Direct associations involve the relationship between concepts that are adjacent in the means–end chain. Indirect associations, in contrast, correspond to virtual relations along the chain, characterized by concepts mentioned together.

Various attributes of eco-design packaging appear to be the source of consumer perceived risks in the food product purchasing process (e.g., recycled materials, shape, color, high price, and quality) (Please see Figure 3). In addition, the aggregated hierarchical map reveals four potential eco-packed product consumption patterns based on perceived risks (Please see Figure 3 in bold). The first pattern corresponds to the functional and physical risk-oriented consumption (black chain in bold), generated by the attribute “recycled materials”, which prevents the selection of eco-packaged food products in a search for “personal well-being” (n = 5) (Total number of direct and indirect relations showing the dominance of the patterns.) and “family security” (n = 5). The second pattern corresponds to the life standard risk-oriented consumption (blue chain in bold) associated with shape and color, which prevents the selection of the eco-packaged food products for “pleasure” (n = 8). The third pattern corresponds to the financial risk-oriented consumption (red chain in bold), specifically poor value for money, as reflected in the “high price” (n = 8) and “lower quality level”, with respect to ordinary packaging. A fourth pattern relates to the socio-environmental risk-oriented consumption (green chain in bold), such as “food waste” (n = 3), usually generated by “overpackaging” (n = 3).

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

The present exploratory study makes several theoretical contributions to the field of marketing. It focuses on the influence of consumers’ perceived risks towards eco-design packaging during the eco-packaged product purchasing decision process. This issue relates to several important marketing concepts.

The first concept is that of eco-design packaging. This study uses an analytical approach to show the main attributes of eco-design packaging. We thus combine an industrial perspective with a consumer perspective to increase the understanding of eco-design packaging. Most previous work has investigated the effects of attributes such as size, color [43,80], shape [44], or a combination of two attributes (e.g., size and volume) [45,81,82] on consumers’ behaviors. In contrast, this study focuses upon consumers’ overall perception of eco-design packaging and the influence of the role of the attributes of this packaging on the decision-making process through an analysis of cognitive chains. This concern uncovers the mechanism underlying the attributes of packaging and the relationships between products and packaging. Moreover, this study agrees with the conclusions of the study by Boesen, Bey and Niero [26] regarding the gap between consumer perceptions and industrial definitions (i.e., the LCA results) toward eco-packaging attributes. More precisely, the attributes that can be perceived by the consumer are more limited than those of the LCA results (please see Table 3). Some attributes are common to both the consumer and the LCA perspective, such as recyclable materials, lighter weight, smaller size, color (e.g., green, blue, or transparent), and sustainable labeling.

In addition, this study contributes to the field of responsible consumption research, in which little attention has been paid to consumers’ perceived risks of eco-design packaging. Most studies dealing with the effects of sustainable attributes upon consumers’ responses (attitudes and behaviors) have focused on the perceived advantages and values of this type of packaging. For instance, Magnier and Schoormans [7] showed that consumers believe that sustainable packaging generates two categories of benefits: Individual and public. Individual benefits are associated with people’s selfish tendencies, such as seeking security or pleasure. In contrast, public benefits correspond to altruistic benefits. The issue is that positive perceptions of eco-design packaging do not account for the low actual purchasing. Individual decision-making theory [83] posits that consumers assess both the benefits and the risks a product may bring them. Hence, it is necessary to view the issue from a more comprehensive perspective that includes perceived risks, as advocated by consumer psychology researchers [84]. Perceived risks are seen as the result of negative consequences and uncertainty. This study has highlighted 11 risks of eco-design packaging, as perceived by the discussion group participants.

Through an examination of cognitive chaining, this study has also shown the underlying cognitive structures of consumers [62]. This approach is used to identify the role of perceived risks in consumers’ decision-making processes by linking packaging attributes, the consequences or risks emanating from the consumption process of eco-packaged products, and individual values. The analysis results show that consumers’ choices are influenced by five types of perceived risks.

Functional risks are associated with the main functions of eco-design packaging. Previous studies [85,86] have shown that packaging plays a key role in consumers’ behaviors, such as assessing and accepting products [86,87]. The traditional functions of packaging can be classified into two categories: Technical functions and marketing functions. The development of packaging, however, has extended its functions. Vila and Ampuero [88] argue that beyond these two key functions, another category of functions has developed, associated with a set of elements constituting the marketing mix, such as the product, price, distribution, and promotion. Assessing the quality of products is influenced by the attributes of the product as reflected in the packaging. If the packaging is perceived as offering a good quality level (i.e., preservation and product use), consumers believe that the product’s quality is equally good. In this exploratory study, eco-design packaging was perceived as being of poor quality because of its attributes: Recycled or recyclable materials and simplified packaging. We observed that consumers tend to link functional risks with other types of risks, such as financial, physical, and eco-responsible risks. Financial risks are connected with poor value for money in consumers’ minds. In particular, reduced or simplified packaging appears to disappoint consumers who view this initiative as a strategy to increase the product’s price, especially when they pay the same price for a reduced quantity. Finally, the issue of poor packaging performance, in terms of its protection and preservation function, is viewed as one of the major causes of health problems and food waste.

Physical risks: Findings show that consumers are concerned about the key packaging functions of product protection and preservation. The majority of consumers express serious doubts about “recycled materials” and the “manufacturing information” of eco-design packaging, since these attributes are directly linked to the perceived health safety of the products. In terms of the health belief model [89,90], people are motivated to take preventative action if they perceive the threat of a health risk to be serious. In the realm of food consumption, perceived risks involve the perceived risk severity and the vulnerability of the packaged products. Rogers [91,92] explains that people’s intentions to adopt a behavior of food product consumption is governed by their motivation to protect themselves from any perceived health-related risks, which reflects the values of “personal well-being” and “family security” used in this study. Our results appear contradict some other studies of consumer attitudes towards eco-packaging, which concluded that the ecological characteristics of packaging produce health-related long-term value through the protection of the planet [7].

Financial risks: This study’s findings show that most consumers (89%) perceive the cost of eco-packaged products to be higher than that of ordinary products. Consumers tend to link product price to packaging performance (i.e., product protection and preservation). Previous studies focusing on consumers’ willingness to pay for the eco-responsible attributes of products have been inconclusive. The pioneering work of Kassarjian [93] demonstrated the existence of a positive correlation between less polluting petrol and consumers’ willingness to pay for this type of petrol [94]. However, Boivin, Durif and Roy [20] indicate that financial and functional deterrents are the most significant factors explaining why positive attitudes do not lead to actual purchasing behavior.

Life standard risks may be viewed as the negative valence of the life standard value. The latter is defined as the sensations produced mainly by the materials, colors, shapes, and sizes of packaging [95]. Consumers’ perceptions of colors appear to affect the image of the product and the brand [96], their purchasing intention [96], and their attitudes towards the product [80]. Our results show that green or transparent packaging influences emotions, induces feelings of nature and calm, and signals more ecological packaging and healthier food products. However, a few consumers said that green packaging is hard to identify in the product category, next to other colors such as blue or red. Similarly, the shape of eco-design packaging (round and curved) arouses aesthetic responses in consumers. These responses constitute an interaction between the packaging’s shape and the person who perceives it. A few female participants stated that the water bottle is not round enough and carries an unfeminine image. Finally, a combination of the size and extremely elongated shape of the water bottle gives the impression that the bottle contains less water than an ordinary bottle.

Socio-environmental risks: Swaen and Chumpitaz [97] show that the transaction of signals related to corporate social responsibility enhances consumers’ trust in products. In our study, however, consumers expressed a lack of trust (26%) in eco-design packaging because they saw this type of packaging as a marketing strategy to increase sales. Apart from this lack of trust, consumers believed that eco-design packaging, particularly packaging manufactured from recyclable materials, does not reduce loss and food waste. Simplified packaging, particularly no packaging (i.e., selling bulk products), is not viewed as an effective way to protect products and does not provide important information (e.g., the sell-by-date, list of ingredients, instructions for use, and place of origin) explicitly.

6.2. Methodological Contributions

This study illustrates how to use MEC analysis to explore consumers’ perceived risks of eco-design packaging. MEC was initially introduced by Young and Feigin [61] into consumer behavior research. MEC is an efficient tool to explain how consumers obtain their desired end states, namely individual values, by consuming a product or service (that is viewed as an ensemble of diver attributes). This technique was then developed by Gutman [62] and Reynolds and Olson [98] to investigate consumer preference, motivation, and consumer segmentation.

This study provides two insights for using MEC to investigate consumer reactions towards eco-design packaging and sustainable products. First, MEC does not only explore the positive/desirable consequences (e.g., the benefit) of consuming a product but also the negative/undesirable consequences (e.g., the risk). Second, because of its efficiency and objectivity, an individual interview with the given A-C-V Cards may be a more efficient data collection technique than a traditional interview [23].

6.3. Managerial Implications

From a practical perspective, the marketing manager and packaging designer play an important role in improving packaging design. This study provides the following actionable suggestions:

First, this study reveals that there is a gap between how the package is designed (i.e., based on the LCA indices) and how the package is actually perceived by consumers. This finding can be insightful for both marketing managers and packaging designers. For marketing managers, this study indicates that the eco-design packaging attributes that can be perceived by consumers is more limited than those defined in the LCA. Some attributes make more sense from a consumer perspective, such as recyclable materials, lighter weight, smaller size, color (green, blue, or transparent), and sustainable labeling. Hence, marketing managers should consider these attributes to improve their mix-marketing strategies and better guide consumers toward sustainable purchasing decisions. However, marketing managers should avoid the practice of greenwashing. For packaging designers, eco-design packaging and/or packaging innovation in general could gain more insight from consumer behavior research [99]. Packaging designers should take attributes that can be easily perceived by consumers instead of only optimizing packaging from an industry perspective.

Moreover, consumers have several concerns related to the current functions of eco-design packaging (e.g., their efficiency of preservation and communication). Hence, we suggest that packaging designers should include these concerns in their packaging development procedures. For instance, it is important to improve the preservation and conservation functions to reduce potential hygiene and health risks. Likewise, improving the aesthetic aspects (i.e., reducing life standard risk) of eco-design packaging would help promote such packaging.

6.4. Political Implications

For policy makers, these findings show that consumers have various concerns regarding eco-design packaging that prevent them from choosing an eco-design product during their purchasing procedures. These concerns include efficiency (functional risk), price (financial risk), aesthetics (life standard risk), and sustainability (socio-environmental risk). These concerns are due to a lack of relevant knowledge of eco-design (in particular, life-cycle assessment techniques) and packaging functions. Therefore, policy makers should develop new eco-design packaging labeling systems and relevant legislation for each product category. This solution could clarify the indices that are measured to attenuate consumers’ perceived risks and, in turn, guide consumers’ purchasing decisions. We also suggest that the government encourages eco-design packaging through innovation competitions and financial support. In addition, the eco-design packaging should be perceived as a tool for marketing products as more efficient (e.g., energy efficient, easy to use and/or reuse, and easy to recycle) instead of as a tool for greenwashing. Thus, policy makers should improve current eco-design regulations adapted for each product category in order to control greenwashing.

Lastly, even with their high potential social and environmental impacts, eco-design packaging has not yet fully integrated into the circular economic framework in Canada. Thus, we suggest that the Canadian government, instead of just the packaging industry, take eco-design packaging into account from the outset.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This exploratory study developed an MEC analysis of consumers’ cognitive structures regarding eco-design packaging. Moreover, the research process was based on (1) data triangulation (i.e., combining two data collection approaches: A focus group and individual interviews with two comparative heterogenous demographic samples) and (2) method triangulation (i.e., analyzing academic and professional literature, content analysis, and an analysis of cognitive chaining) to obtain more robust results, thereby strengthening the research’s validity.

However, due to the exploratory nature of this study, several limitations remain. Firstly, due to the sample (n = 19) of individual interviews, this study cannot generalize its findings related to consumers’ cognitive chains to all consumers. Moreover, this study revealed four risk-oriented consumption patterns associated with eco-design packaging (i.e., functional and physical risks-oriented consumption patterns, life standard risk-oriented consumption patterns, financial risk-oriented consumption patterns, and socio-environmental risk-oriented consumption patterns).

Through a hierarchical map linking attributes, consequences, and values (Please see Figure 3). Note that this representation of static cognitive chaining cannot lead to an inference of causality. Future research may seek to establish a representative of cognitive chaining to build a dynamic causal model of A-C-Vs with a representative sample (around fifty) [23].

Secondly, this study focused upon the negative reactions of consumers, namely their perceived risk. Future studies focusing upon the positive reactions of consumers (e.g., perceived benefits and perceived quality) through an MEC approach are recommended to gain a complete understanding of the topic.

Another limitation is that this study focused upon food packaging in a Canadian context. A survey of Eco Entreprises Quebec shows that Canadian consumers have a higher awareness of eco-design packaging in food categories (57.1%) than in other product categories, including medication (10.6%) and cleaning products (9.0%) [100]. The findings for individual cognitive chains may be different across divers product categories. Thus, a future study may investigate consumers’ perceptions towards eco-packaging across different product categories (e.g., cleaning products and cosmetic products). However, we expect similar findings to the food packaging sector.

Lastly, the results of this exploratory study have demonstrated the socio–environmental risks related to packaging. In particular, 26% of consumers interviewed stated that eco-design packaging could cause food waste because of its simplicity, reduction, or poor quality. These results seem to contradict most of the findings of previous consumer studies on the influence of packaging on food waste behaviors, which showed instead that reduced packaging reduces food waste [30,101,102,103]. These inconsistent results may be due to the particular sample and/or an oversight of some effects of key variables (e.g., the effects of time). Hence, it is necessary to perform a confirmatory study of these experimental studies by integrating the effect of time, to investigate the causal relationship between consumers’ perceptions towards eco-design packaging and their food waste behaviors.

Author Contributions

T.Z. conducted the literature review, the data collection, the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. F.D. supervised the research and conducted the data collection.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample of the focus group.

Table A1.

Sample of the focus group.

| Variables | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 3 | 38% |

| Female | 5 | 63% | |

| Average age | 36 | ||

| Marital status | Single, never married | 2 | 25% |

| In a domestic partnership or civil union | 2 | 25% | |

| Married | 3 | 38% | |

| Divorced | 0 | ||

| Widowed | 1 | 13% | |

| Origin | Quebec | 4 | 50% |

| Other Provinces in Canada | 0 | ||

| Other Countries | 4 | 50% | |

| Education | No diploma | 0 | |

| High school graduate | 1 | 13% | |

| Certificate | 2 | 25% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 | 25% | |

| Master’s degree | 2 | 25% | |

| Ph.D. | 1 | 13% | |

| Number of Children | No child | 5 | 63% |

| 1 | 1 | 13% | |

| 2 | 1 | 13% | |

| More than 2 | 1 | 13% | |

| Total | 8 | 100% | |

Appendix B. Guide of the Focus Group

Present three different types of eco-design packaging in front of participants:

- A cheese bag made of 100% recycled plastic that is easy to reclose

- A water bottle that improves content/container (product/packaging) ratio (i.e., using the same quantity of 100% recycled rPET plastic contains more water).

- A box of granola bars that use less cardboard.

Table A2.

Questions.

Table A2.

Questions.

| Topics | Open–End Questions | Complementary Questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceptions regarding eco-design packaging attributes | What are your impressions regarding these packs? | |

| 2. Consequences relating consumption of eco-design packaging | What do you think about the initiative of eco-design packaging? | |

| 3. Evaluation criteria in purchasing decisio | Can eco-design packaging change your mind when you are shopping? |

|

Appendix C

Table A3.

Sample of Individual Interviews.

Table A3.

Sample of Individual Interviews.

| Variable | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8 | 42% |

| Female | 11 | 58% | |

| Age | 18–24 | 6 | 32% |

| 25–34 | 10 | 53% | |

| 35–44 | 1 | 5% | |

| 45–54 | 2 | 11% | |

| Martial status | Single, never married | 10 | 53% |

| In a domestic partnership or civil union | 4 | 21% | |

| Married | 5 | 26% | |

| Divorced | 0 | 0% | |

| Widowed | 0 | 0% | |

| Origin | Quebec | 8 | 42% |

| Other Provinces in Canada | 0 | 0% | |

| Other Countries | 11 | 58% | |

| Education | No diploma | 0 | 0% |

| High school graduate | 2 | 11% | |

| Certificate | 1 | 5% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 | 11% | |

| Master’s degree | 13 | 68% | |

| Ph.D. | 1 | 5% | |

| Total | 19 | 100% | |

Appendix D

Table A4.

Multiple adjustment scores of non-linear canonical analysis.

Table A4.

Multiple adjustment scores of non-linear canonical analysis.

| A-C-V’s | Orientations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Attributes | Recycled materials (e.g., recycled cardboard, recycled plastic, biodegradable plastic, wood) | 0.047 | 1.213 | 0.091 |

| Recyclable materials | 0.099 | 0.063 | 0.013 | |

| Reduced packaging/no overpackaging | 0.205 | 0.6 | 0.293 | |

| Shape (round, curved, delicate) | 0.268 | 0.229 | 0.029 | |

| Eco-labeling (FSC logo, recyclable) | 0.008 | 0.035 | 0.272 | |

| Color (green, blue, transparent, white, brown) | 0.11 | 1.169 | 0.146 | |

| Clear manufacturing information | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.231 | |

| High price | 0.535 | 0.014 | 0.009 | |

| Packaging quality | 0.011 | 0.02 | 0.743 | |

| Consequences | Value for money | 0.002 | 0.087 | 0.085 |

| Protection effectiveness | 0 | 0.075 | 1.385 | |

| Communication quality (difficult to understand the information presented on the packaging) | 0.065 | 0.027 | 0.051 | |

| Hygiene/cleanliness sacrifice | 0.054 | 1.389 | 0.767 | |

| Health/health safety | 0.636 | 1.195 | 0.414 | |

| Pleasure during the consumer experience (hedonism) | 0.003 | 0.84 | 0 | |

| Practicality | 0.361 | 0.157 | 0.182 | |

| Respect for the environment | 0.736 | 0.708 | 0.11 | |

| Food waste | 0.026 | 0.648 | 0.405 | |

| Aesthetic sacrifice | 0.012 | 0.505 | 0.117 | |

| Trust/credibility towards the product and the brand | 0.496 | 0.438 | 0.51 | |

| Values | Capable (competent, effective) | 0.328 | 0.069 | 0.003 |

| Logical (coherent, rational) | 0 | 0.001 | 0.286 | |

| Intellectual (intelligent, thoughtful) | 0.003 | 1.018 | 0.241 | |

| Honest (sincere, frank) | 0.019 | 1.847 | 0.807 | |

| Responsable (accountable, reliable) | 0.033 | 5.858 | 0.498 | |

| Enjoyment and excitement/pleasure (pleasant unhurried life) | 1.427 | 0.084 | 0.003 | |

| Happiness (satisfaction) | 0.271 | 0.28 | 0.025 | |

| Family security (taking good care of loved ones) | 0.229 | 1.774 | 0.112 | |

| Inner harmony (for personal well-being/security) | 0.181 | 1.299 | 0.065 | |

Note: The dominant items are the items have the highest multiple adjustment score (in bold). The dominant items can discriminate one A-C-V’s orientation from another.

Appendix E

Table A5.

Terminology and definition of the core concepts.

Table A5.

Terminology and definition of the core concepts.

| Term | Explanation | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Means–end chain (or cognitive chaining) | The term “Means–end chain” is used to describe the theoretical framework and research method. However, the term “cognitive chaining” is used to presented research method and results. Cognitive chaining describes the connection between product attributes (the “means”), the consequences consumers derive from those, and the potential links with consumers’ values (the “end”). More precisely, cognitive chaining links three successive levels of abstraction: Attributes, consequences, and values (A-C-V′s structure). Cognitive chaining can identify the consumer purchasing decision process and behavior patterns associated with a product (i.e., eco-design packaging). | Figure 1 |

| Consequence | The term “consequence” only refers to second a level variable (A-C-V’s). It is measured by 17 items. | Table 1 |

| Risk | The term “risks” refers to the aggregated concept from the findings. The authors use the term “risks” to describe the consumer segments (Table 6) and their risk-oriented consumption patterns (Figure 3). | Table 6 Figure 3 |

| Orientation | The term “orientation” refers to the typology of A-C-V’s structure. For instance, the orientation A3-C3-V3 in the 3rd line of Table 6 corresponds to: A (Clear manufacturing information)–C (Hygiene/cleanliness sacrifice, Communication quality)–V (Honest, Responsible). | Table 6 |

| Consumption segment | The term “consumption segment” describes a group of consumers who share the common characteristics. This study identifies three consumer segments based on their perceived risk associated with eco-design packaging: (1) Eco-conscious consumers, (2) Utilitarian-minded consumers, and (3) Skeptical consumers. | Table 6 |

| Consumption pattern | The term “consumption pattern” describes consumer consumption A-C-V structure based on the perceived risks associated with eco-design packaging. This study revealed four consumption patterns: (1) a functional and physical risks-oriented consumption pattern, (2) a life standard risk-oriented consumption pattern, (3) a financial risk-oriented consumption pattern, and a (4) socio-environmental risk-oriented consumption pattern. | Figure 3 |

References

- Rundh, B. Packaging design: Creating competitive advantage with product packaging. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 988–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brach, S.; Walsh, G.; Shaw, D. Sustainable consumption and third-party certification labels: Consumers’ perceptions and reactions. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, T. Éco-conception des emballages. Techniques de L’ingénieur; L’Entreprise Industrielle: Saint-Denis, France, 2000; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Magnier, L.; Crié, D. Communicating packaging eco-friendliness. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F. L’impact d’un Packaging Simple sur la Perception du Produit. In Proceedings of the 14ième Colloque Doctoral de l’Association Française de Marketing, 13 et 14 mai 2014 à Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 13 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, J.-C.; Chang, H.-T.; Chen, S.-B. Factor Analysis of Packaging Visual Design for Happiness on Organic Food—Middle-Aged and Elderly as an Example. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J. Consumer reactions to sustainable packaging: The interplay of visual appearance, verbal claim and environmental concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzan, G.; Cruceru, A.; Bălăceanu, C.; Chivu, R.-G. Consumers’ Behavior Concerning Sustainable Packaging: An Exploratory Study on Romanian Consumers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J.; Mugge, R. Judging a product by its cover: Packaging sustainability and perceptions of quality in food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 53, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.; Smith, J.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J. Against the Green: A Multi-method Examination of the Barriers to Green Consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, E.; Ryan, G.; Ginieis, M. Towards a Holistic Approach of the Attitude Behaviour Gap in Ethical Consumer Behaviours: Empirical Evidence from Spain. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2011, 17, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett-Baker, J.; Ozaki, R. Pro-environmental products: Marketing influence on consumer purchase decision. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K.; Petersen, L.; HöRisch, J.; Battenfeld, D. Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do Consumers Care about Ethics? Willingness to Pay for Fair-Trade Coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Potter, S. The adoption of cleaner vehicles in the UK: Exploring the consumer attitude–action gap. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T. Do What Consumers Say Matter? The Misalignment of Preferences with Unconstrained Ethical Intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T. Impacts des Perceptions de L’éco-Packaging sur les Achats de Produits Éco-Emballés. Master’s Thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GreenUXlab ESG UQAM. Baromètre Greenuxlab/MBA Recherche des Nouvelles Tendances de Consommation en Commerce de Détail; GreenUXlab ESG UQAM: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, C.; Durif, F.; Roy, J. Buying Socially Responsible Goods: The Influence of Perceived Risks Revisited. World Rev. Bus. Res. 2011, 1, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Gutman, J. Laddering theory, method, analysis, and interpretation. J. Advert. Res. 1988, 28, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Valette-Florence, P. Introduction à l’analyse des chaînages cognitifs. Rech. Appl. Mark. 1994, 9, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, J. Analyzing consumer orientations toward beverages through means–end chain analysis. Psychol. Mark. 1984, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauer, E.; Wohner, B.; Heinrich, V.; Tacker, M. Assessing the Environmental Sustainability of Food Packaging: An Extended Life Cycle Assessment including Packaging-Related Food Losses and Waste and Circularity Assessment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, S.; Bey, N.; Niero, M. Environmental sustainability of liquid food packaging: Is there a gap between Danish consumers’ perception and learnings from life cycle assessment? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, S.; Beckenuyte, C.; Butt, M.M. Consumers’ behavioural intentions after experiencing deception or cognitive dissonance caused by deceptive packaging, package downsizing or slack filling. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; François, J.; Durif, F. How Consumers React to Environmental Information: An Experimental Study. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiman, K.; Ortega, D.L.; Garnache, C. Perceived barriers to food packaging recycling: Evidence from a choice experiment of US consumers. Food Control 2017, 73, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Wetter-Edman, K.; Kristensson, P. Decisions on recycling or waste: How packaging functions affect the fate of used packaging in selected Swedish households. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Giorgi, S.; Sharp, V.; Strange, K.; Wilson, D.C.; Blakey, N. Household waste prevention—A review of evidence. Waste Manag. Res. 2010, 28, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 101, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Monetary Incentives and Recycling: Behavioural and Psychological Reactions to a Performance-Dependent Garbage Fee. J. Consum. Policy 2003, 26, 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on Attitude-Behavior Relationships: A Natural Experiment with Curbside Recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiesser, P. Eco-efficience, analyse du cycle de vie & éco-conception: Liens, challenges et perspectives. In Annales des Mines—Responsabilité et Environnement; Cairn: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, T.; Ertz, M.; Durif, F. Examination of a Specific Form of Eco-design. Int. J. Manag. Bus. 2017, 8, 50–74. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.R. Marketing Communications: An Integrated Approach, 4th ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management, 14th ed.; Pearson France: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, R.L. The Communicative Power of Product Packaging: Creating Brand Identity via Lived and Mediated Experience. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2003, 11, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, R.; Brewer, C. The verbal and visual components of package design. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2000, 9, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantin-Sohier, G.; Bree, J. L’influence de la couleur sur la perception des traits de personnalité de la marque. In Revue Française du Marketing; Sage: Paris, France, 2004; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pantin-Sohier, G. L’influence du packaging sur les associations fonctionnelles et symboliques de l’image de marque. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2009, 24, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B. Can package size accelerate usage volume? J. Mark. 1996, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Van Ittersum, K. Bottoms Up! The Influence of Elongation on Pouring and Consumption Volume. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, M. The influence of shape on product preferences. Adv. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 559. [Google Scholar]

- Raghubir, P.; Greenleaf, E.A. Ratios in proportion: What should the shape of the package be? J. Mark. 2006, 70, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Raghubir, P. Les bouteilles peuvent-elles être transcrites en volumes? L’effet de la forme de l’emballage sur la quantité à acheter. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2006, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.-P. Vers une clarification du concept de packaging: Nécessité d’une approche interdisciplinaire. In Proceedings of the 16ème Colloque National de la Recherche dans les IUT, Angers, France, 9 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Dobscha, S. L’efficacité de la participation consciente à promouvoir la durabilité sociale. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2014, 29, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François-lecompte, A.; Valette-florence, P. Mieux connaitre le consommateur socialement responsable. Décis Mark. 2006, 41, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.; Johns, N.; Kilburn, D. An Exploratory Study into the Factors Impeding Ethical Consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volle, P. Le concept de risque perçu en psychologie du consommateur: Antécédents et statut théorique. Rech. Appl. Mark. 1995, 10, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valette-Florence, P. Analyse structurelle comparative des composantes des systèmes de valeurs selon Kahle et Rokeach. Rech. Appl. Mark. 1988, 3, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L.R.; Kennedy, P. Using the List of Values (LOV) to Understand Consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 1989, 6, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, L.B.; Szybillo, G.J.; Jacoby, J. Components of perceived risk in product purchase: A cross-validation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, A.-C.; Picot-Coupey, K.; Droulers, O. Mesurer le risque perçu à <jouer responsable>. Journal de Gestion et D’économie Médicales 2014, 32, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlena, W.J.; Desarbo, W.S. On the Measurement of Perceived Consumer Risk. Decis. Sci. 1991, 22, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ferran, F. Différentiation des Motivations à la Consommation de Produits Engagés et Circuits de Distribution Utilisés, Application à la Consommation de Produits Issus du Commerce Équitable; Ecole Dotorale d’Economie et de Gestion: Aix-en-Provence, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.; Feigin, B. Using the benefit chain for improved strategy formulation. J. Mark. 1975, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, J. A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization processes. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.C.; Reynolds, T.J. Understanding consumers’ cognitive structures: Implications for advertising strategy. Advert. Consum. Psychol. 1983, 1, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gengler, C.E.; Klenosky, D.B.; Mulvey, M.S. Improving the graphic representation of means-end results. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valette-Florence, P.; Ferrandi, J.-M.; Roehrich, G. Apport des chaînages cognitifs à la segmentation des marchés. Décis. Mark. 2003, 32, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973; Volume 438. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Gutman, J. Advertising is image management. J. Advert. Res. 1984, 24, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brieu, M.; Durif, F.; Roy, J.; Prim-Allaz, I. Valeurs et risques perçus du tourisme durable-le cas du SPA Eastman. Rev. Fr. Mark. 2011, 232, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rundh, B. The multi-faceted dimension of packaging: Marketing logistic or marketing tool? Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoluci, G.; Trystram, G. Eco-concevoir pour l’industrie alimentaire: Quelles spécificités ? Marché Organ. 2013, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berneman, C.; Lanoie, P.; Plouffe, S.; Vernier, M.-F. Démystifier la mise en place de l’écoconception. Gestion 2013, 38, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conseil National de l’emballage. Eco-Design of Packaged Products: Methodological Guide; Conseil National de l’emballage: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kahle, L.R.; Beatty, S.E.; Homer, P. Alternative measurement approaches to consumer values: The list of values (LOV) and values and life style (VALS). J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Birks, D. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, D.; Birtwistle, G.; Macedo, N. Food retail positioning strategy: A means-end chain analysis. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Wiedenfeld and Nicholson: London, UK, 1967; Volume 24, pp. 288–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Thomas, J.B.; Clark, S.M.; Chittipeddi, K. Symbolism and strategic change in academia: The dynamics of sensemaking and influence. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, K.G.; Gioia, D.A. Identity Ambiguity and Change in the Wake of a Corporate Spin-off. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 173–208. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. Corp SPSS Statistics for Windows, 23.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roullet, B.; Droulers, O. Pharmaceutical Packaging Color and Drug Expectancy. Adv. Consum. Res. 2004, 32, 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Krider, R.E.; Raghubir, P.; Krishna, A. Pizzas: π or square? Psychophysical biases in area comparisons. Mark. Sci. 2001, 20, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, V.; Matta, S. The effect of package shape on consumers’ judgments of product volume: Attention as a mental contaminant. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.F.; Stone, E.R. Risk appraisal. Risk-Tak. Behav. 1992, 92, 49–85. [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn, H.J.; Hogarth, R.M. Decision making: Going forward in reverse. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1987, 65, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, S. The Measurement of the Effect of a New Packaging Material Upon Preference and Sales. J. Bus. Univ. Chic. 1950, 23, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, C.; Baker, R.C. Convenience Food Packaging and the Perception of Product Quality. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoormans, J.P.L.; Robben, H.S.J. The effect of new package design on product attention, categorization and evaluation. J. Econ. Psychol. 1997, 18, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]