The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Development and Sustainable Tourism

- sustainable management;

- socio-economic effects;

- impact on culture;

- environmental impact (including resource consumption, pollution reduction, and preservation of biodiversity and landscapes).

2.2. Overtourism

2.3. Travel by Generations

- Baby Boomers (BB)—born in 1945–1964, the so-called generation of the baby boom and economic boom;

- Generation X—born in 1965–1980, growing up during the economic crisis of the 1970s;

- Generation Y (Millennials)—born in 1981–1994, brought up in the era of globalization and universal access to the Internet;

- Generation Z—born after 1995, which uses modern information and communication technology for everything.

3. Materials and Methods

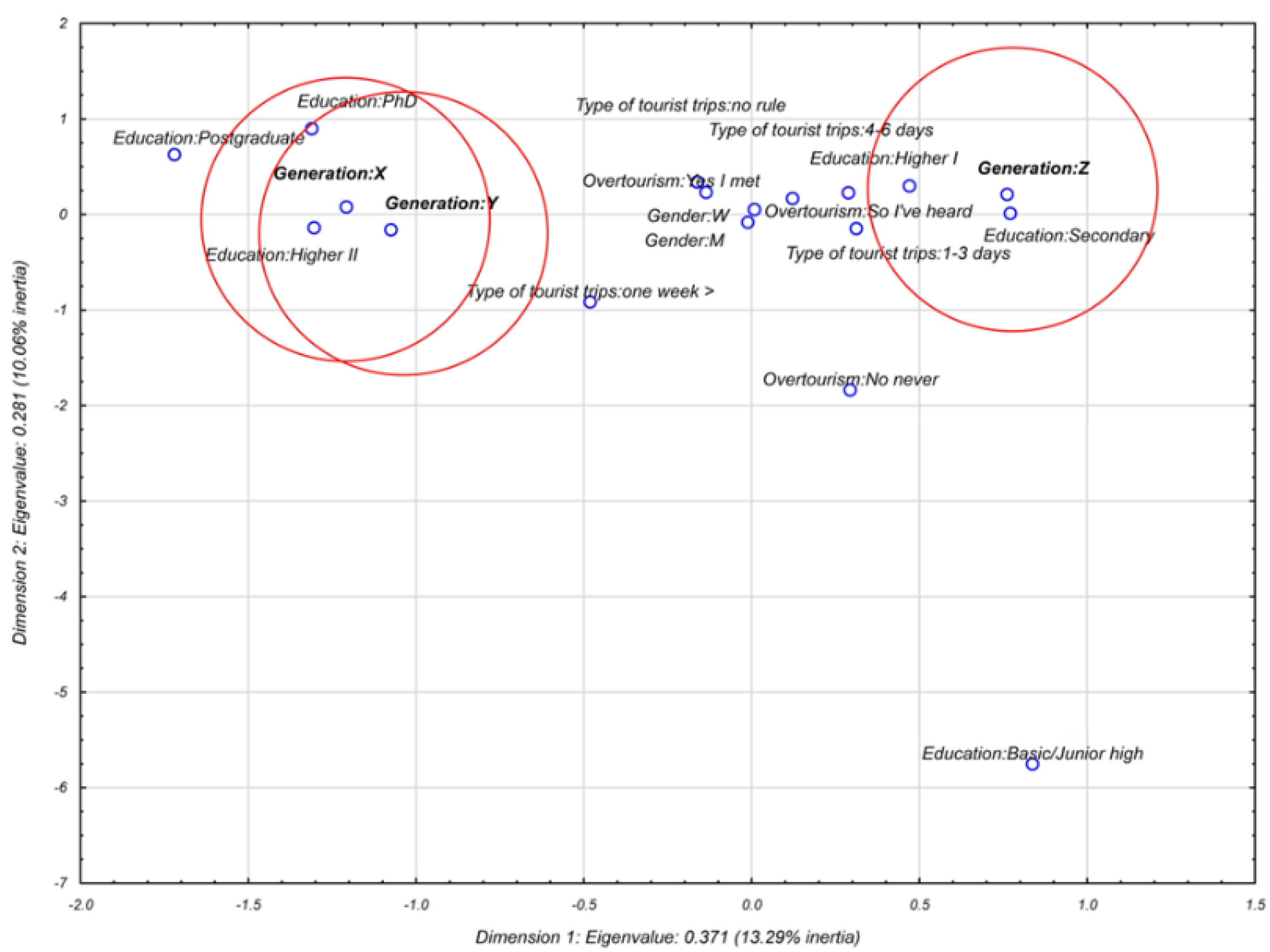

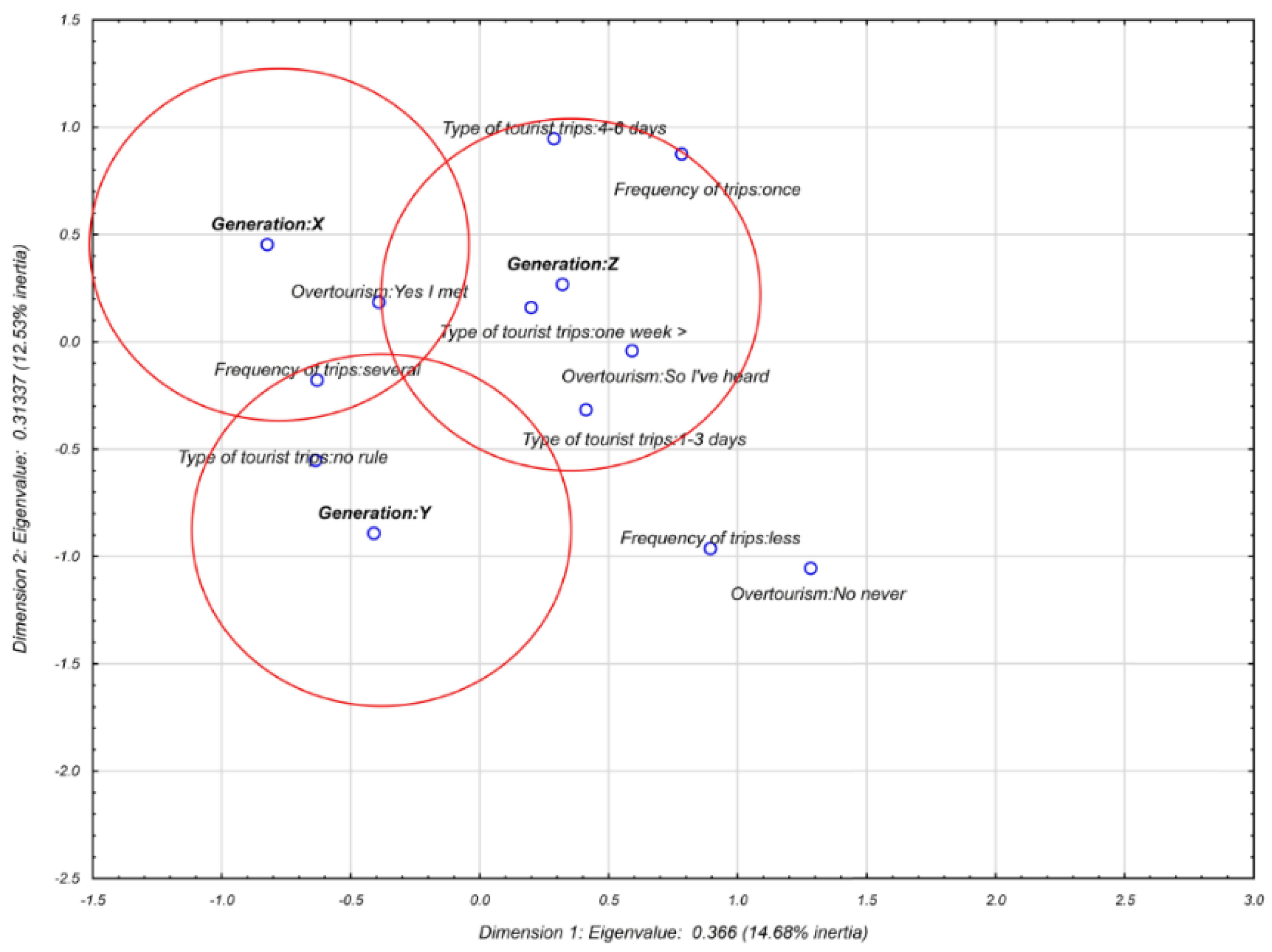

4. Results of Research

- During the trip, I do not litter the environment, I do not make noise, and I turn off electrical devices when leaving the hotel room (average rating is 1.48 ± 0.78);

- I always behave in a civilized way, no matter where I am (the average rating is 1.48 ± 0.80);

- During the trip, I use natural resources in the same way as in my home (the average rating is 1.08 ± 1.00);

- My presence in a tourist location means only benefits for residents (the average rating is 0.26 ± 1.00);

- I pay for the holiday, so I can use the local amenities however and whenever I want (average rating is 0.06 ± 1.28);

- To be honest, it is not my concern–I want to relax when I feel like it (average rating is 0.04 ± 1.39);

- This is an exaggeration–in my opinion, the negative impact of tourists is exaggerated (the average rating is −0.30 ± 1.04);

- During the trip, I sometimes use more water for washing and more electricity than at home (the average rating is −0.51 ± 1.29);

- I believe that during a tourist trip I am free to do more, I am on holiday after all (average score is −0.61 ± 1.30);

- I do not intend to deal with what the residents think about my presence and behavior (average score is −0.76 ± 1.16).

- Indifference to the phenomenon of overtourism was demonstrated by the youngest respondents (Z generation). Their results of agreement with the opinion that overtourism is not their concern are similar and positive, which means that they generally agree with this opinion. Intermediate groups of respondents (X and Y generations) do not agree with indifference to this phenomenon. Comparative analysis between the generations confirmed that there is a statistically significant difference between the average ratings of the X and Z generations (p < 0.001) and Y and Z (p = 0.020).

- In general, all respondents agree that tourist visits are associated with benefits for residents. Generation Y agrees with this statement much more often than people from other generations, in which there is a greater tendency to an intermediate response (difficult to say/I do not know).

- In the case of opinions that the popularity of the phenomenon of overtourism results from exaggerating its real significance, the responses are unambiguous. All generations negatively refer to this statement, which means that in generations X, Y, and Z the problem of overtourism is perceived as serious.

- The distribution of responses on the subject of higher water and electricity consumption during tourist stays is interesting. The respondents from all generations disagree with this opinion, while it is twice as emphatic in Generation X than in the Y and Z generations, which show great similarity in this respect (p = 0.767).

- The opinion on whether during the tourist trip the respondents were allowed more than in everyday life did not gain approval. In general, the ratings obtained were negative, and in Generation X, strong opposition to this opinion was more frequently expressed (−1.14 ± 1.08).

- A material factor related to the opinion that a tourist has the right to use the destination freely, since they pay for it, did not gain the approval of the X and Y generations, while the people of Generation Z rather agree with this view (0.41 ± 1.17).

- For all generations of tourists, the opinion of residents on their behavior in the destination turns out to be important. This is indicated by average ratings in all groups, with higher averages again in generations X and Y.

- The above result seems to be consistent with what was obtained in the study on the responses of respondents from different generations on their opinions about their manners during the trip. All generations agree that their civilized behavior does not depend on where they are, and therefore is identical in a holiday spot and the home environment.

- In the next question, in order to control the reliability of responding, one of the previously asked questions was repeated (but in the opposite context). It was a question about similar consumption of natural resources at home and during a tourist trip. The answers obtained confirm the reliability of the research tool, because the average scores are very similar to those given when asked about water and electricity consumption. Of course, the results were positive this time, because they were put in a positive context.

- The respondents generally strongly agreed with the statement that they do not litter the environment, do not make noise, and turn off electrical devices while leaving the hotel room. What is noticeable here is the fact that the frequency of confirming this opinion decreases with the increasingly lower age of respondents (Table 2).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Tourism Organization, International Tourism Highlights 2019 Edition. UNWTO, Madrid. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284421152 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Turystyka w UE, GUS. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/kultura-turystyka-sport/turystyka/turystyka-w-unii-europejskiej-dane-za-2017-rok,11,4.html (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- World Tourism Organization and United Nations Development Programme Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030, Highlights, UNWTO, 2017, Madrid. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419401 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Dickinson, G. A timeline of overtourism: Key moments in global battle between locals and travelers, The Telegraph, 21 August 2019. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/news/timeline-action-against-overtourism/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Portal Samorządowy. Available online: https://www.portalsamorzadowy.pl/wydarzenia-lokalne/miasta- nie-potrzebuja-turystow-szaranczy,133542.html (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Oklevik, O.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Kristian, J. Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: A case study of activities in Fjord Norway. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotopoulos, A.; Pisano, C. Overtourism Dystopias and Socialist Utopias: Towards an Urban Armature for Dubrovnik. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechlaner, H.; Innerhofer, E.; Erschbamer, G. (Eds.) Overtourism: Tourism Management and Solutions; Series: Contemporary Geographies of Leisure, Tourism and Mobility; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions | World Tourism Organization. Available online: www.e-unwto.org (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Google Website. 2019. Available online: https://trends.google.pl/trends/explore?q=Overtourism (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Dolot, A. The Characteristics of Generation, Z; E-mentor, Warsaw School of Economics: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grenčíková, A.; Vojtovič, S. Relationship of generations X, Y, Z with new communication technology. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2017, 15, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, A. Zarządzanie różnorodnością pokoleniową. Zeszyty naukowe Politechniki Śląskiej 2016, 97, 385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, L.; Robinson, J.; Cutsor, J.; Brase, G. Sustainable Development. In Solar Powered Infrastructure for Electric Vehicles: A Sustainable Development; Erickson, L., Robinson, J., Brase, G., Cutsor, J., Eds.; Taylor and Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Statistic. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tourism_ industries_-_employment] Source: Eurostat (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- GUS. 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/kultura-turystyka-sport/turystyka/baza-noclegowa-wedlug-stanu-w-dniu-31-lipca-2019-r-i-jej-wykorzystanie-w-pierwszym-polroczu-2019-roku,4,16.html (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Kuznetsov Viktor, S. An integrated approach to tourism development in protected natural areas. Arct. North. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Lam, C.F.; Haobin Ye, B. Barriers for the Sustainable Development of Entertainment Tourism in Macau. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council. GSTC Criteria for hotels. GSTC Criteria for tour operators. GSTC Criteria for destinations. Available online: http://www.gstcouncil.org/gstc-criteria/ (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Perkumiene, D.; Pranskuniene, R. Overtourism: Between the Right to Travel and Residents’ Rights. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Alvarez, M.D.; Ertuna, B. Barriers to stakeholder involvement in the planning of sustainable tourism: The case of the Thrace region in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. How Cities Around The World Are Fighting Overtourism. 2019. Available online: ttps://www.forbes.com/sites/ lesliewu/2019/05/26/how-cities-around-the-world-are-fighting-overtourism/#20f554db212a (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- McKinsey & Company, & World Travel & Tourism Council. Coping with success: Managing overcrowding in tourism destination. 2017. Available online: https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/ policy-research/copingwith-success---managing-overcrowding-in-tourism-destinations-2017.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.H.S.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S. Research for TRAN Committee—Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies Directorate-General for Internal Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek, Z. Ways to Counteract the Negative Effects of Overtourism at Tourist Attractions and Destinations. In Annales—Universitatis Mariae Curie-Sklodowska, Sectio B, VOL. LXXIV; University School of Physical Education: Kraków, Poland, 2019; pp. 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey, G.V. A causation theory of visitor/resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences. In Proceedings of the Travel Research Association 6th Annual Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 September 1975; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of tourism area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R.W. Overtourism. Issues, Realitis and Solutions. In De Gruyter Studies in Tourism 1; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek, Z. “Overtourism”—around the definition, Encyclopedia, 2019, v1. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/163 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Coping with success managing overcrowding in tourism destinations, 2017, McKinsey & Company & World Travel & Tourism Council. Available online: https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/policy-research /coping-with-success---managing-overcrowding-in-tourism-destinations-2017.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Xiang, Z.; Magnini, V.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Information Technology and Consumer Behaviour in Travel and Tourism: Insights from Travel Planning Using the Internet. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expedia Group Media Solutions survey, “Multi-generational travel trends. Travel habits and behaviours of Generation Z, Millennials, Generation X, and Baby Boomers”. Available online: https://info.advertising.expedia.com/british-travel-and-tourism-trends-research (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Globetrender Website. Available online: https://globetrender.com/2019/05/11/overtourism-crisis/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Zmyślony, P.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Urban tourism hypertrophy: who should deal with it? The case of Krakow (Poland). Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.T. Venice: the problem of overtourism and the impact of cruises. Investig. Reg.—J. Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, M. From overtourism to sustainability: A research agenda for qualitative tourism development in the Adriatic. German J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 92213, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W.; Szromek, A.R. Incorporating the Value Proposition for Society with Business Models of Health Tourism Enterprises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Making Tourism More Sustainable—A Guide for Policy Makers; UNEP and UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2005; pp. 11–12. Available online: http://www.unep.fr/shared/publications/pdf/DTIx0592xPA-TourismPolicyEN.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Joseph, M. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: A Journey through Four Decades of Tourism Development, Planning and Local Concerns. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 14, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smola, K.W.; Sutton, C.D. Generational differences: Revisiting generational work values for the new millennium. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolbik-Jęczmień, A. Rozwój kariery zawodowej przedstawicieli pokolenia X i Y w warunkach gospodarki opartej na wiedzy. Nierówności Społeczne a Wzrost Gospodarczy 2013, 36, 228–238. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur-Wierzbicka, E. Kompetencje pokolenia Y—wybrane aspekty, Studia i prace Wydziału Nauk Ekonomicznych i Zarządzania Nr 39, t. 3; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego: Szczecin, Poland, 2015; pp. 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- McCrindle, M. The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations Kindle Edition; McCrindle Research Pty Ltd.: Sydney NSW, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, S.T.; Schweitzer, L.; Ng Eddy, S.W. How have careers changed? An investigation of changing career patterns across four generations. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, N.; Bolton, A.; Parasuraman, A.; Hoefnagels, A.; Migchels, N.; Kabadayi, S.; Gruber, T.; Loureiro, Y.K.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Y and Their Use of Social Media: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267. [Google Scholar]

- Naidooa, P.; Ramseook-Munhurrunb, P.; Seebaluckc, N.V.; Janvierd Procedia, S. Investigating the Motivation of Baby Boomers for Adventure Tourism. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, K.L.; Benjamin, B.J.; Biermeier-Hanson, B.B.J.; Baltes Early, B.J.; Shepard, A. Generational Differences in Work Ethic: Fact or Fiction? J. Bus. Psychol. Sci. Bus. Media 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupperschmidt, B.R. Multigeneration employees: Strategies for effective management. Health Care Manag. 2000, 19, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukic, M.; Kuzmanovic, M.; Kostnic Stankovic, M. Understanding the Heterogeneity of Generation Y’s Preferences for Travelling: A Conjoint Analysis Approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębski, M.; Krawczyk, A.; Dworak, D. Wzory zachowań turystycznych przedstawicieli Pokolenia Y. In Studia i Prace Kolegium Zarządzania Finansów, Zeszyt Naukowy 172; Uniwersytet Warszawski: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.C.; Veiga, C.; Aguas, P. Tourism Services: Facing the Challenge of new Tourist Profiles. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2016, 8, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, A.; Fyall, A.; Byron, P. Generation Y: An Agenda for Future Visitor Attraction Research. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Nang Fong, L.H.; Law, R.; Luk, C. An Investigation of Gen-Y’s Online Hotel Information Search: The Case of Hong Kong. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Petrick James, F. Generation Y’s Travel Behaviours: a comparison with Baby Boomers and Generation X. In Tourism and Generation Y; Beckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre, M.; Hastie, T. The Geometric Interpretation of Correspondence Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1987, 82, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisz, A. (Ed.) Biostatystyka; Wyd. Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2005; pp. 109–409. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M.G. Multivariete Analysis; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1975; pp. 3–198. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Tourism_statistics#Tourism_expenditure:_highest_spending_by_German_residents (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Hanna, P.; Font, X.; Scarles, C.; Weeden, C. Harrison Ch: Tourist destination marketing: From sustainability myopia to memorableexperiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Sziva, I.P.; Olt, G. Overtourism and Resident Resistance in Budapest. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Carnicelli, S.; Krolikowski, C.; Wijesinghe, G.; Boluk, K. Degrowing tourism: rethinking tourism. J. Sustain. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generations | [%] | Length of Tourist Trips | [%] |

| X | 19.7% | no rule | 33.6% |

| Y | 21.5% | 1–3 days | 27.0% |

| Z | 58.8% | 4–6 days | 26.5% |

| one week > | 12.9% | ||

| Level of Education | [%] | Frequency of Tourist Trips | [%] |

| Basic/Junior high | 1.0% | less than once a year | 15.4% |

| Secondary | 38.6% | once a year on average | 28.3% |

| Higher I | 27.5% | several times a year | 56.3% |

| Higher II | 30.8% | ||

| Postgraduate | 1.0% | ||

| PhD | 1.0% | ||

| Gender of Respondents | [%] | Knowledge about Overtourism | [%] |

| Woman | 59.8% | Yes, I met this phenomenon personally | 67.7% |

| Man | 40.2% | I heard about it from the media/friends | 20.7% |

| No, I've never encountered it | 11.1% |

| What do You Think About Your Own Impact on the Inhabitants’ Environment and the Environment in the Visited Tourist Destinations? | Generations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation (Median) | |||

| To be honest, it is not my concern—I want to relax when I feel like it | 0.49 ± 1.44 | −0.13 ± 1.33 | 0.27 ± 1.34 |

| My presence in a tourist location means only benefits for residents | 0.16 ± 1.09 | 0.45 ± 0.86 | 0.21 ± 1.01 |

| This is an exaggeration—in my opinion, the negative impact of tourists is exaggerated | −0.5 ± 1.11 | −0.44 ± 1.04 | −0.24 ± 0.96 |

| During the trip, I sometimes use more water for washing and more electricity than at home | −0.85 ± 1.21 | −0.47 ± 1.16 | −0.47 ± 1.32 |

| I believe that during a tourist trip I am free to do more, I am on holiday after all | −1.14 ± 1.08 | −0.88 ± 1.21 | −0.36 ± 1.33 |

| I pay for rest, so I can use the local amenities whenever I want and when I want | −0.65 ± 1.18 | −0.36 ± 1.25 | 0.41 ± 1.17 |

| I do not intend to deal with what the residents think about my presence and behavior | −1.14 ± 1.01 | −0.96 ± 1.01 | −0.58 ± 1.21 |

| I always behave in a civilized way, no matter where I am | 1.58 ± 0.73 | 1.49 ± 0.79 | 1.45 ± 0.85 |

| During the trip, I use natural resources in the same way as in my home | 1.27 ± 0.99 | 1.06 ± 0.94 | 1.05 ± 1.02 |

| During the trip, I do not litter the environment, I do not make noise, and I turn off electrical devices when leaving the hotel room | 1.58 ± 0.69 | 1.52 ± 0.74 | 1.43 ± 0.84 |

| Opinion on Own Impact on the Tourist Area and Residents | Level of Significance of Differences between Generations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| XZ | XY | YZ | |

| To be honest, it is not my concern—I want to relax when I feel like it | 0.001 | 0.088 | 0.020 |

| My presence in a tourist location means only benefits for residents | 0.854 | 0.093 | 0.043 |

| This is an exaggeration—in my opinion, the negative impact of tourists is exaggerated | 0.034 | 0.685 | 0.076 |

| During the trip, I sometimes use more water for washing and more electricity than at home | 0.027 | 0.026 | 0.767 |

| I believe that during a tourist trip I am free to do more, I am on holiday after all | 0.001 | 0.142 | 0.002 |

| I pay for rest, so I can use the local amenities whenever I want and when I want | 0.001 | 0.147 | 0.001 |

| I do not intend to deal with what the residents think about my presence and behavior | 0.001 | 0.209 | 0.019 |

| I always behave in a civilized way, no matter where I am | 0.221 | 0.371 | 0.839 |

| During the trip, I use natural resources in the same way as in my home | 0.054 | 0.041 | 0.805 |

| During the trip, I do not litter the environment, I do not make noise, and I turn off electrical devices when leaving the hotel room | 0.218 | 0.557 | 0.553 |

| I Think that My Presence in A Tourist Destination May Affect: | Generations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation (Median) | |||

| Economic situation of residents (living costs, income) | 1.37 ± 0.66 | 1.33 ± 0.79 | 1.14 ± 0.95 |

| State of relations of residents (family/neighborly/friendly) | 0.6 ± 0.74 | 0.51 ± 0.79 | 0.41 ± 0.85 |

| Communication possibilities (moving, parking) | −0.18 ± 1.03 | −0.22 ± 1.02 | −0.22 ± 1.18 |

| Comfort of recreation for residents in their free time | −0.07 ± 1.02 | −0.13 ± 1.01 | 0.01 ± 1.13 |

| Religious practices and access to culture by local people | 0.25 ± 0.81 | 0.19 ± 0.73 | 0.19 ± 0.88 |

| Satisfaction of residents with professional life | 0.92 ± 0.81 | 0.76 ± 0.77 | 0.88 ± 0.83 |

| Residents’ access to social infrastructure | 0.49 ± 0.92 | 0.44 ± 0.95 | 0.46 ± 1.06 |

| Sense of security on the streets | 0.42 ± 0.82 | 0.27 ± 0.92 | 0.25 ± 1.02 |

| Sense of pride of residents for belonging to the city | 0.76 ± 0.76 | 0.79 ± 0.77 | 0.83 ± 0.90 |

| Condition of the natural environment in the town | 0.01 ± 1.06 | 0.14 ± 1.05 | 0.09 ± 1.12 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szromek, A.R.; Hysa, B.; Karasek, A. The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247151

Szromek AR, Hysa B, Karasek A. The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations. Sustainability. 2019; 11(24):7151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247151

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzromek, Adam R., Beata Hysa, and Aneta Karasek. 2019. "The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations" Sustainability 11, no. 24: 7151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247151

APA StyleSzromek, A. R., Hysa, B., & Karasek, A. (2019). The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations. Sustainability, 11(24), 7151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247151