1. Introduction

Modern day tourism has been growing rapidly all over the world. This is due to the increase in income and quality of global society life [

1]. In addition, the number of modern technologies that are used to support tourism and tourist attractions is growing. Especially interesting are mobile applications that include records regarding tourist infrastructure in a region. In most cases, those apps can be co-created by tourists and the entries are based on their experiences.

Mobile applications can be seen as the easiest technological solutions to adopt, which can improve tourism in a region. There are many already existing services that contain databases of touristic points of interest. Therefore, a region that transforms into a tourist destination does not need to develop its own platform, but rather start by marking its presence in those databases. Those allow visitors to search for attractions, hotels and restaurants. This makes tourists aware of their surroundings in a given area. As we later discuss, most of such applications not only allow users to search for touristic objects, but they can also be reviewed. This changes the classical model of a touristic product and puts the consumers into the role of co-producers. Those reviews are perceived as a powerful source of impact on other tourists, who orientate themselves based on such reviews, and see them as the most reliable source of information. Adopting mobile tourism (m-tourism) is also one of the main pillars of the smart tourism concept, which has become more and more popular. As a result, tourists expect certain destinations to support a proper technological infrastructure and also be able to use mobile solutions, not only for searching attractions but also for booking hotels, finding restaurants, sharing experiences and reviews. Destinations that adapt to those demands are more likely to be chosen by the part of potential tourists who only rely on such internet-based solutions for trip planning or by those who will prefer such destinations over those that did not adapt to the smart tourism concept. This implies that m-tourism presence and support become a necessity in almost every touristic region, especially in the developing ones that aspire to become a well-recognized and desired destination (especially by tourists out of a given country, who discovered it by themselves and had no opportunity to get recommendations from the local community that is familiar with it). The Upper Silesian metropolitan area in Poland is a good example of such a region. Since the 1990s, the once known for heavy industry area, has started to transform into a post-industrial region. This has left the region with a lot of heritage, both in the form of cultural and industrial monuments. Many former mines, factories, and other facilities have become museums, restaurants, galleries and other tourist attractions, where cultural heritage is presented and preserved, making it also a sustainability issue.

The idea of sustainable development emphasizes finding a use for material and non-material values that are socially important and would be lost if no other action was taken [

2]. Heritage tourism fits well into this category since it allows artifacts, old technology and culture to be saved from the past, which would otherwise perish because there are no other applications for it that would generate sufficient income to sustain it [

3]. Therefore, the process of transformation from a former industrial facility to a touristic site that conserves heritage is a sustainability issue and can be well explained through the perspective of business models [

2]. Such an approach can be applied to single entities from various branches of tourism [

4,

5], but also to a set of touristic sites that try to improve in their efforts to reach sustainable development, through cooperation and trust-building [

6]. In the widest perspective, part of the sustainable development goals of a touristic region could be achieved through a business model applied to whole cities or metropolis. Such an approach can be found in the concept of smart tourism, which utilizes technology to reach its goals and is the tourism-orientated part of the smart city concept (with falls into the category of sustainable business models) [

7,

8].

In Upper Silesia, there are two industrial heritage sites that have been inscribed on the World Heritage Site’s list by UNESCO—with one of them quite recently in 2017 [

9]. This illustrates well that the Upper Silesian transformation into a worldwide known and recognizable touristic destination is still in process and makes a good case for studying how smart technology use develops and is applied to support such transformation, illustrating the early stages of the smart tourism concept application.

Therefore, the paper’s aim was to observe and measure how the presence of touristic sites from the Silesian region develops in mobile applications. In our work, we focus on 14 mobile applications that are used to find tourist attractions, hotels and restaurants. It is based on research that was conducted in 2015 [

10], and now we compare the result of that research with data collected in 2019. The paper is divided into two sections. In the first one, we focus on a literature review on digital technology use in tourism, smart tourism concepts and business models in tourism. In the second part, we examine the functionality of selected mobile applications and we compare the results with previous ones. The area we refer to in our research is the Silesian Voivodeship in the southern part of Poland.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Modern Technology in Sustainable Tourism

Tourism is one of the most significant world markets. The UNWTO report [

11] indicates that in 2017, international tourist arrivals increased by 6% in comparison to the previous year. As a result, it can be seen that tourism is constantly evolving. Development is visible in all fields of tourism. It is especially evident in the area of digital technologies. Mobile apps, interactive museums, virtual and augmented reality are only a few examples of modern technology that emerged in recent years. To understand what modern technology really is, it is important to discuss both terms.

Technology may be defined as a composition of two primary components—the physical one, which contains products, technics, and processes, and the second one, which is information that contains the know-how, marketing, and quality control [

12]. The term “modern” is commonly understood as everything that nowadays is in use and is also frequently associated with any electronic elements. This point of view is confirmed by the Cambridge Dictionary (available online). In connection with those definitions, modern technology can be understood as a set of components (joined together physically and by information) that are used nowadays and can be used interchangeably with digital technologies.

Modern technologies have found an application in all life areas in the modern world. It is easy to find examples in medicine, enginery, psychology or military science. Digital technologies are used in tourism as well. As an example, one can name the reservation system. The popularity of the CRS (computer reservation system) has been growing since the 1990s. Its basic function is to store information about all available service providers and to transfer such data between users. In comparison with traditional models of reservation, CRS significantly increases the rate of service sales by eliminating the physical distance between the producer and the consumer [

13]. To name another example, the tour-guide system is a commonly known one. It is used in many tourist attractions and frequently is associated with recordings. Digital technologies have increased their functionality. The technology was expanded by touchscreens, video projections, the Internet and even GPS systems. For this reason, the guide end-user system provides few capabilities such as access to extended information, the possibility to send and receive messages or access to interactive services [

14].

A new way of using “commonly known” technology is Smart CCTV (closed-circuit television). This technology significantly extends the functionality of CCTV and, in addition to the security function, enables to recognize the behavior of tourists and, as a consequence, better planning of tourism space [

15,

16]. Another idea is the beacon technology which is used to deliver extended information about exhibits by short-range signal transmitters [

17]. In the context of modern technologies in tourism, augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) are frequently pointed out. These two technologies offer some benefits to human experience. The major advantages of VR are personalization, interactivity, and full immersion which have a significant influence on explaining the main phenomena [

18]. AR, although it works differently (do not create reality, only adds some virtual objects to available space), has a similar effect to explaining the main phenomena.

An example of technology that suggests itself in the described context are mobile applications. Mobile technologies are correlated with the growing use of smart phones, that have been popularized and made known by Apple’s iPhone. Their App Store, soon followed by the Google Play Store, started in 2008 [

19]. In 2011, it was one of the fastest-growing media outlets in the history of consumer technology [

20]. Since that time, the mobile market has considerably increased and today it can no longer be seen as a curiosity, but as a major part of life and business. Take the Gartner report [

21] for instance: mobile apps are projected to have the most impact on business success by 2020. Without doubt, smartphones and mobile applications are an important part of everyday life also in tourist activity. In Poland, above 58% of smartphone users have been using them to book hotels, planes or make car reservations [

22]. One of the most popular mobile platforms:

Trip Advisor has over 490 billion users every month. On the basis of the above data, it is possible to predict that the market of smartphones and mobile applications will grow and it is necessary to examine its dynamics. Moreover, those technologies are directly connected with the idea of smart tourism.

A study published in 2018 focused on how tourists’ risk perception affects their use of mobile devices, and the results suggest that there is no single digital tourist profile. Risk perception by tourists who use mobile devices is an important sustainability factor, because it is shaping their experience, through its influence on tourist behavior and satisfaction with a service. Tourist destinations should include a smart tourism policy in their efforts to promote a destination and it is suggested to include the perception of risk. The referred research shows that there is a dependence between mobile device dependence and its usefulness, but also that privacy risk has a major negative impact on the tourist experience (yet it does not affect future use of mobile devices and their perceived utilitarian value) [

23]. This is crucial since the tourist experience is believed to be the essence of modern tourism [

24], and it is also considered to become increasingly impactful on value co-creation [

25].

Nowadays, the use of mobile devices like smartphones, tablets, etc., is so broadly spread that they have become a standard resource, also used by tourists to search for experiences, places and attractions. This behavior influences both the way information reaches tourists and the way they are acting during a holiday [

26,

27]. A modern tourist business should be aware of this and respond through its management to the elements that shape tourist behavior regarding this medium, not only by single actions but by incorporating it into its business model [

23].

In modern tourism, the use of technology and mobile phones in particular, puts tourists into the role of co-producers of tourist experiences [

28,

29,

30]. Tourist destinations that emphasize on introducing smart tourism are dependent on technology, making the attractions available and appealing to tourists trough this media, but also allowing them to co-shape the product by reviewing it, sharing opinions, recommendations, etc.

Those shared opinions, recommendations, ratings, etc., have also another meaning for a tourist destination. All tourist areas, no matter the size (from villages, cities, regions or countries) are (or at least should be) monitoring and constantly improving the destinations’ image and attractiveness [

31]. This topic was in the scope of researchers for decades [

32]. The sources of factors that affect the formation and change of a tourist destination image can be divided into three groups: organic (originating and transmitted by individuals), induced (coming from the entities that promote a region) or autonomous (not related to the previous two) [

33,

34].

The first group contains all activities of word of mouth marketing, like sharing information with friends, family, and work colleagues, and is best known under its informal name: grapevine. In modern days, this form of creating opinions about destinations is therefore, also building or ruining its image, and becomes expanded by technology. User-generated content that includes opinions or recommendations that are shared over social media, websites, services, apps, etc., is an electronic form of word of mouth marketing (eWoM) [

35]. Thanks to the constant development of technology and increasing meaning, and use and application of electronic media by tourists, the eWoM has undergone many changes in the course of the last 10 years from online guides and blogs to portals and mobile apps, that are now the most widely used medium for online tourist reviews [

36]. Those can be used by researchers, as E. Marine-Roig has shown [

35], to examine a well-known tourist destinations’ image, that emerges from online reviews. The same data can be useful for local administration, promoters of a tourist region and entrepreneurs, in terms of gathering feedback about their single product or about the whole destination in general and its image.

This implies that in order to meet the requirements of modern tourists, a region that aspirates to develop an advanced tourist function should undertake actions that will ensure its presence in those widely used social apps and services. After this is achieved, the feedback from online tourist reviews offers a plenteous source of information that is easily accessible (compared to conducting reviews, surveys, etc.), and can be used for creating sustainable development plans which can incorporate solutions for current, environmental, civil, juridical and touristic problems found in a region.

Online reviews in tourism and hospitality are perceived as a significant factor that nowadays strongly impacts the decision-making process of a consumer [

25,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Those sources are even considered to be seen by customers as more reliable and believable than information coming from third party and product vendors [

41,

42,

43]. As mentioned before, this puts the customers in the role of co-creators of a tourist experience but also makes those reviews valuable information sources for the service provides [

44,

45]. Therefore, one can say that the role of online reviews and ICT’s (Information and Communication Technologies) in tourism are bilateral and conjunctive; on the one hand, they are an information source for potential tourists that make decisions based on that information, and on the other hand, during and after the consumption of a touristic product, they are used for sharing experiences, opinions, and recommendations [

46]. Due to the above, ICT is frequently an inseparable element of business models in tourism enterprises.

2.2. Business Models in Tourism

Business models are a popular issue among researchers. The phrase "business model" as keywords in ScienceDirect returns over 350,000 research articles. This popularity is due to a few factors. The first one is the practical dimension. A good created business model is frequently indicated as one of the most important factors of success in business [

47]. The second factor is cognitive value. Analyzing existing business models allows to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of an organization, and it also allows to identify trends in business and indicate success factors. The third is the number of tools for creating the business model.

Such great interest in the issues of business models is also caused by the disagreement regarding the definition of the business model. It is understood differently, depending on the researcher’s scientific discipline. The literature review allows us to assume that the business models are understood in two ways. The first one is a synthetic description of the company’s operation. J. Magretta is one of the scholars who follows this approach and who explains the business model as a story that explains how enterprises work [

48]. The second way is to understand the business model as a tool to create value for customers. It is mentioned by D. Teece, who describes the business model as a tool to design the mechanism of creating, describing and capturing value for customers [

49]. Regardless of the approach to the characteristics of business models, numerous researchers agree that it consists of several components. Researches conducted by M. Morris et al. [

50] and Shafer et al. [

51] refer to this. The first team analyzed 19 perspectives on business model components. As a result, these researchers prepared six questions that describe a business model, and based on the answers, six major components of a business model could be created: factors related to offering (how the value is created), market factors, internal capability factors, competitive strategy factors, economic factors, and growth/exit factor. The second team analyzed 12 definitions of business models and specified 42 different components (unique building blocks or elements) that make a business model. In that research, they organized all ideas into four categories based on their similarity: strategic choices, create value, value network, and capture value.

One of the most popular conceptions is the business model CANVAS. The idea was developed and disseminated by A. Osterwalder and Y. Pigneur [

52]. They include a framework based on nine elements: customer segments, value propositions, channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partners, and cost structure. These nine elements are widely used as a tool to create new business models and describe existing ones. Another example is the Cube business model. It consists of seven blocks: value proposition, users and customers, value chain, competences, networks, relations and value formula [

53]. Another example is the proposal of M. Johnson et al. [

54]. It contains four elements of a “Successful Business Model”: value proposition for the client, profit formula, key resources, and key processes. Literature analysis shows significant differences in the components of business models. However, one element is common. It is the value that the company offers to its clients.

Business models described in the context of providing tourist services often refer to modern technologies. E. Cranmer et al. [

55] point out the possibility of creating value by using augmented reality (AR). This technology gives the opportunity to present collections to which access is difficult (e.g., delicate exhibits). Researchers also describe the possibility of sharing such a tool by many entities, whereby the belonging of many museums to a common network allows them to create virtual exhibitions, extending the presented heritage with exhibits or collections owned by other units. Thanks to AR, exhibits can be better protected and made available to tourists and other entities in the form of models without the risk of damage. Therefore, digital technologies enable the creation of a joint virtual exhibition, extending the heritage presented by exhibits or owned collections by values owned by other units. In the opinion of C. Ciurea and F. G. Filip [

56], virtual exhibitions are also an excellent opportunity to correlate museum collections located in various cultural units such as museums, libraries, archives, and galleries. The combination of these units, although only virtual, causes a real increase in the number of visitors and in the revenue stream.

N. Langvould and I. Daunoraviþinjtơ [

57], in a publication on factors that influence the success of a business model in the hospitality service industry, show that technology is one of the most important factors because it can reduce the cost of business. In addition, technology has a strong relationship with other factors, which include internal and external marketing, relationship management, innovation, value proposition, and employee competencies.

The fundamental importance of modern technologies in creating business models was noted by M. Diacon and A. Dutu [

58]. Those researchers claim that the development of new technologies has become a way to achieve success because it offers the possibility of expanding distribution channels, shortens the time of booking processing and creates a network of organizations involved in maintaining the value chain.

F. Mantaguti and E. Mingotto [

59] show that knowledge is important in business models. Especially, it applies to knowledge generated by stakeholders, such as public institutions, local governments, business partners and even volunteers. Organizations using such knowledge effectively can become flexible enterprises, where entrepreneurs and their employees are in some sense creative agents, for whom customer relations are a priority. Modern technologies are used to gather and process knowledge because of their generality.

Modern technologies, their development and the attractiveness of their use, have caused business models to evolve. One of the directions of this development is the Smart Tourism concept.

2.3. Smart Tourism

Smart tourism is quite a new idea. The basis of it can be found in Web 2.0 conception. The term has been widely used to describe the role of technologies for modern tourists. Tourists are no longer passive but active [

60]. They co-create tourist services through the opinions they leave on the Internet. In connection with this, a lot of companies have been obligated to change their products or even their business models. The idea of co-creating services seems tempting also for managers of tourist attractions. The era of m-tourism 2.0 has begun. This conception, described by Beça [

60], enables users to get access to extended information that may help enrich their experience, provide their own opinions and get feedback or update some information in the future. This holistic approach is the basis of the smart tourism idea. Smart tourism may be defined as the integrated efforts of entities in destination to collect, aggregate and use data that could be transformed into on-site experiences and business value-propositions [

61]. It seems reasonable to assume that it is the future of tourism. Big data, as a total experience of tourists, tourism attractions, government, tourist companies or even residents, could be used to create better touristic products.

The topic of sustainability in tourism roots back to the 1960s, when global tourism entered a rapid growth [

62], and it was a response to negative effects in regions overblown by tourists, like inflation, increasing crime rate, rising housing prices, negative influence on local society (especially children) and higher number of strangers in previously sheltered neighborhoods [

63]. The primal sustainable solutions for establishing sustainability in tourism reached out to the (back then) most influential methods, but technology was left out and not perceived as a key aspect in this matter [

63]. As already mentioned before, over the last decades, things have changed dramatically, and now the use of modern technology is an inevitable part of tourism, which should be used for the benefits of sustainable development. D. Kim and S. Kim [

64] researched the role of technology in achieving sustainable tourism by conducting a complex review of papers, news, mobile apps, and patents. The conclusion drawn from their research shows that the impact of mobile technology on sustainability is hard to measure directly, but can be deduced quantitively from frameworks already established in literature, since the environmental effects of tourism and cultural heritage, as well as ICT’s role in creating smart city communities, are all subjects of sustainable tourism discussions [

65,

66,

67,

68]. Mobile applications enhance the social capital by offering resources for tourist to tourist relations and the instant communication that can take place through them can be used by the transactors to share value and build cultural capital. Those among others positively affect sustainability. Furthermore, ICTs can be used to obtain big data, and perform large scale measurements and analysis, sometimes even in real-time. This allows them to track environmental impacts, support decision making and accelerate the introduction of new policies.

In the area of business models in tourism, special attention is paid to innovations in value propositions in business models, such as the use of new technologies. They significantly extend the value that companies can offer to their customers. Noteworthy is the recently popular concept of Smart Tourism [

61], which is based on transforming huge amounts of data obtained through an application (usually mobile) into a value proposition for the client. In tourism, VR technology is increasingly being used, which makes it possible to get to know a space that is inaccessible to a client. This is emphasized by E. Crammer [

55], who points out that, on the one hand, it may diversify the offer of a venture, and on the other hand, it contributes to increasing the competitiveness of that venture and increases its profits.

Smart tourism is a subset of the smart city concept in which the main idea is to connect people, business processes and systems, government and other entities together, with the main goal of improving the life quality of all citizens [

7]. In other words, a smart city concept is essentially a business model of a city that is oriented at reaching specific goals with the use of innovative systems and processes. Smart city concepts focus on ICTs, platforms that allow engaging stakeholders, data generation and analysis coming from big data and open data sources [

8]. This concept also focuses on human capital and information management [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72]. This meaning, it is oriented at using employees’ skills to produce desired outcomes. Smart tourism is the outcome of applying a smart city concept in a tourist destination, so that some of the developed solutions can enhance tourist experience, by automating some of the processes or improving their efficiency [

73,

74]. Therefore, smart tourism provides an interface between the visitor and the destination, allowing them to meet their needs [

7]. Moreover, smart tourism requires the use of innovative solutions, that cover all main areas of sustainability (environmental, sociocultural, economic) while spreading cultural heritage to tourists [

7,

69].

According to some authors [

7], destinations that apply the smart tourism concept incorporate three components:

Cloud services—those provide access to technological solutions in the form of applications, software, and data [

75].

Internet of things—it is responsible for control and automation in providing destinations with information management and analysis [

75].

End-user Internet Service System—they are designed to provide users (tourists) with applications (and sometimes equipment) that allow access to tourist-oriented services (booking, payment, internet access, finding destinations and attractions, etc.).

Those means serve to accomplish one of the main goals of smart tourism, that is—to create and manage tourist experiences [

76]. Thanks to this, it is possible for multiple tourists to draw different, individual experiences from the same product offered by a destination [

77].

In the light of all findings from various studies shown above, one can conclude that the smart tourism concept is virtually a necessity in destinations that aspire to become a tourist region or try to maintain such function. Modern tourists expect to find information about destinations, attractions, hotels, restaurants and locally available experiences, in apps, social media and other web-oriented services. They also expect to find a proper ICT infrastructure on-site, so they can continuously use those services, not only to find new places and activities but also to share those experiences with friends, family and other tourists, as well as for booking and regulating payments. Upon returning home, they want to review and recommend (or advise against) certain places or service providers. Moreover, those opinions are more likely to be taken into consideration by potential tourists, than content from other sources (advertisements, service providers, third party reviews). This does not only concern the young and middle age, technology-oriented tourists. As a recent study from Spain [

78] has shown, the line of age in which tourists use apps has shifted, and senior citizens are a substantial tourist group that uses ICT technologies, mainly in the pre-travel phase, to book accommodation and transportation, and to locate and search for services and products.

Smart tourism was mainly studied from the perspective of the advantages that it can offer. However, there are also some risks that one should consider. Among those risks one can name [

61,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83]:

Information safety—this includes all sensitive information validations, like payment and location, information, but also storing of digital footprints left by unaware users.

Risk of losing tourists intimidated or unfamiliar with smart technology. Individuals who know that a destination is heavily oriented on smart technologies in tourist services, and do not use them or do not do it with comfort and confidence, might refrain from using such apps or even cancel the trip. This also poses a risk and fear of losing, damaging or misusing those devices.

Risk of losing tourists who are well familiar with modern technology, but get dependent on them, so they make it impossible for tourists to enjoy their travels (fully and uninterrupted).

Even if the chances for some of those events in the first point are very small, the fear of them taking place may place some tourists into feeling discomfort and discourage them from traveling. These issues should also be taken into consideration by smart tourism destinations (local administration, service providers, app designers, etc.) and use appropriate means to avert those negative effects.

3. Research Details

In 2015, one of the authors [

10] conducted an analysis of six mobile tourist apps, that were designed overseas, offer an interface in English and are dedicated for the global market. Those applications were:

Tripadvisor, TripCase, WorldMate, TouristEye, Gogobot, and

EloMaps. During the referenced research three Polish apps, dedicated only for domestic tourists, were also analyzed:

Polska Niezwykła, Polskie Szlaki, and

wyjade.pl. Choosing these two types of apps allowed to compare the number of hotels, restaurants and tourist attractions fond by apps dedicated both to domestic and foreign tourists. Taking apps into account that are dedicated to foreign tourists seems particularly important when one considers that according to the Central Statistical Office’s (CSO) [

83] data, almost every fifth (20.89%) tourist in Poland is a foreigner. The same statistic also says that visitors from other countries make almost a quarter (24.48%) of all hotel guests in Poland.

Some of the mentioned applications no longer operate on the market as for the day of this publication, and some of them were changed to follow a new business model, offering a different functionality compared to 2015. In this research, we collected data from all previously mentioned applications that still operate on the market and from four new ones that have gained popularity during the last four years. The additional apps were:

Airbnb,

Booking.com,

Foursquare, and

Triposo. The criteria for choosing these apps were the same as during the previous research—a high position in the Google Play store when searching for phrases like:

tourist guide,

trip planner,

tourist application. Google ranks its apps higher according to the bigger the user count and user rating, and the better the match with the searched phrase. The subject for the analysis was: the number of hotels, restaurants and tourist attractions found by each app (not all of them allow to search for all three types of objects) in selected cities: Katowice, Chorzów, Bytom, Zabrze, and Gliwice. Those towns have been selected because they were the most visited cities in Silesian Voivodeship during the years 2013 to 2015 (annually approximately 50% of all tourists in this Voivodeship visited these towns) [

84].

Table 1 shows which of the given functions (searching for hotels, restaurants and tourist attractions) were available in 2015 and/or still in 2019, and also how some of the functionality has changed in this time period.

Two of the analyzed applications changed their names over the course of four years (from 2015 to 2019). Gogobot has become Trip by Skyscanner, but the available functions did not change. The second application that was renamed is Guides by Lonely Planet (former TouristEye). Originally, TouristEye allowed, just as similar services do, to search for restaurants and tourist attractions in selected user cities. Nowadays, the business model of this app has changed and it offers access to comprehensive guides through selected cities popular among tourists all over the world (in the case of Poland, as for 2019, there were two guides available through Warsaw and Cracow). Two from the nine apps that were analyzed back in 2015 expired and are no longer available, those are EloMaps and WorldMate. Only three of the services allow to search for all three types of objects (hotels, restaurants and tourist attractions). The presented changes in availability, functionality, and business models show how prone to change and dynamic the application market is. Almost half (5 out of 9) of the previously analyzed applications has undergone no major changes. This dynamic should also affect the development of each app, especially regarding the size of databases that are available for the users. Thus, the next stage of the research was to analyze the amount of tourist objects found by each application.

4. Results

Before analyzing the actual results obtained from mobile applications it is worth to delve into the characteristics of tourism in the Silesian region.

Table 2 contains selected statistical indicators provided by the Polish Central Statistical Office (CSO) for the years 2014–2018, for tourism in the Silesian Voivodeship. One can notice that both the Schneider and Charvat Indexes have been constantly rising during the last five years, indicating that the number of tourists in Silesia has been constantly growing in this period of time. The growth was also noted by the indicator of tourist traffic density. It is also worth noting that even if the index of accommodation establishments per 100 km

2 rose, the tourist accommodation development rate has also risen. This might be interpreted as a sign that the accommodation base develops slower than the tourist traffic in this region. It is also interesting that even if tourism traffic seems to be growing, the number of catering units per every 100 km

2 in 2018 was lower than in the previous four years. Since the whole Voivodeship has an area of 12,333 km

2, it means that the total number of catering units has sunk by around 280. This took place, even though the total number of tourists visiting the Silesian region has been rising significantly since 2013, as presented in the graph in

Figure 1.

As mentioned before, Upper Silesia is developing as an industrial heritage touristic region. This reflects on the number of objects inscribed on the register of monuments, that has been constantly growing over the course of the last five years. It is also worth mentioning that in 2006, the Industrial Monuments Route (IMR) of Upper Silesia was created, and since 2010, the creators (Marshals Office) organize an annual event called

Industriada. It is described as a holiday of the route, during which every site on the route (42 as for 2019) organizes special events (concerts, free tours, educational presentations, etc.). The number of visitors during each

Industriada has been growing every year, and in 2018 it tippled in comparison to the first edition. In

Figure 2, we present a graph that illustrates the growing number of

Industriada participants. One might say that this is the indisputable proof of Upper Silesia developing as an industrial heritage tourist region.

The first of the analyzed functions of mobile tourist applications was the number of accommodation facilities found in selected cities. Out of the 13 applications studied, eight offer or have offered this function (the

WorldMate application is no longer maintained by its authors and its activity has been terminated).

Table 3 shows the results obtained from every application.

The last three applications presented in

Table 1 (

Triposo, Booking.com, and

Airbnb) were only included in the current research, so in their case, the authors did not have data from 2015. The sum of accommodation facilities for applications that have been operating for the last four years has increased (

Tripadvisor, 359.52%;

TripCase, 25.00% and

Trip by Skyscanner, 676.00%). Despite the long period between measurements, the application

wyjade.pl still does not have in its database a single object of the chosen type, for any of the largest cities of the Upper Silesian Industrial District (although the application provides such functionality).

Portals created solely to search for accommodation facilities (Triposo, Booking.com, and Airbnb) returned several times more results than the applications analyzed in 2015 that offer searching for various types of objects. It should also be noted that for all applications, the number of accommodation facilities found in Katowice was many times higher than in other city.

Figure 3 presents a graph comparing the number of accommodation facilities found by each app in 2015 and 2019.

One can notice that for most of the studied applications, the results have changed significantly compared to the figures recorded in 2015. The exception is TripCase, where the latest results increased by only 25% compared to the results from four years ago. All of the previously studied applications also obtained significantly lower results (not exceeding 200 records) compared to newer applications dedicated only for searching accommodation (booking.com and Airbnb), which have found about 500 accommodation facilities. It should be emphasized here that the number of accommodation facilities in the largest cities of Upper Silesia found by Tripadvisor (one of the most popular tourist applications in the world) is also not as large as in the other two applications. This can be an area for improvement among Silesian hoteliers, giving the opportunity to reach potential customers who use only one application to meet all their basic needs. The results from other applications clearly show that the number of hotels in the cities selected for the study has increased (as far as it goes to their presence in mobile applications), but the databases of many applications still do not include a significant proportion of existing facilities. The data from CSO also reflects that the accommodation base in Silesia has been growing, so the clear increase of those facilities’ presence in mobile apps might be caused by the rapidly growing number of tourists visiting this region.

The second of the analyzed quantities was the number of gastronomic establishments found by mobile tourist applications. Out of the 14 services taken into consideration in this study, seven offer this feature.

Table 4 presents the results obtained in 2015 and 2019 by each application.

It can be noticed that within those four years between the described researches, the database of gastronomic establishments in the application

wyjade.pl has not changed and still did not contain a single object in the cities selected for the study. As mentioned earlier, the

Guides by Lonely Planet application was created on the basis of the former

TouristEye service, and its business model changed. Thus, it was impossible to compare the results from 2015 and 2019 in this application. It was similar in the case of

TripCase, which was remodeled into a flight search engine. In the case of applications that retained their original functions (

Tripadvisor and

Trip by Skyscanner), there was a clear increase in the number of gastronomic establishments included in the databases of each service. During the research,

Tripadvisor found a total of 694 objects of this type in selected cities. This is an increase by almost 129% compared to 2015 and, at the same time, the highest result among all applications included in this research. The relatively largest increase in the gastronomic establishments was observed for the

Trip by Skyscanner application (from 13 to 381, which gives an increase of over 2380% compared to 2015).

Figure 4 presents a graph comparing the number of gastronomic establishments found by each application in 2015 and 2019.

It can be seen that over the past four years there has been a development of mobile tourist applications regarding extending databases covering gastronomic establishments. Applications that did not contain a large number of records in 2015 (TripCase and TouristEye) changed their business model and focused on other functionalities. The exception is the portal wyjade.pl, which, despite providing the search function of gastronomic establishments, still does not have any facilities in its database located in major cities of the Upper Silesian metropolitan area. These results, in juxtaposition with the statistical data from CSO, show that despite the decrease in the total number of catering units in Silesian Voivodeship, their presence in mobile apps has been growing, even if not uniformly in every case. This might also be an indication that the number of restaurants in the metropolitan area has been growing, but it did not affect the overall statistic for the whole Voivodeship, which noted a downfall in this matter.

The last of the analyzed aspects of mobile tourist applications was the number of tourist attractions found by them. Out of all 14 applications included in the current and previous study, nine have or had such a function. The only application whose developers terminated it was

EloMaps. As mentioned earlier, the

TouristEye application has been remodeled into a set of guides through selected cities, in which none of the cities selected for this study were included. Two new applications have been included into the current study, due to their development and high positioning in 2019. These are

Triposo and

Foursquare. The number of tourist attractions found by each application is shown in

Table 5.

Since 2015, a significant increase in the number of tourist facilities has been observed in all applications that continued to operate in 2019. The highest number of attractions is contained in the

Polska Niezwykła application’s database (421 facilities in selected cities). In this application, the largest nominal change in the number of objects was noted. It took place in the course of the last 4 years and 152 new objects were added. Regrettably, this application is available only in Polish, which makes it difficult for foreigners to use.

Triposo has the largest number of objects in an application available to foreigners, which has 201 records in its database (therefore, it is not even half of the objects listed in

Polska Niezwykła).

Figure 5 presents a graph comparing the number of tourist attractions found by each application in 2015 and 2019.

It can be noted that in the case of the

wyjade.pl application, the increase in the number of tourist facilities noted in 2019 is still insufficient compared to competing platforms. Domestic tourists using

Polska Niezwykła have access to a much larger database of attractions. For foreign tourists, using the

Trip by Scaner application also seems to be the least favorable option, knowing that

Tripadvisor has a database almost four times larger, and

Triposo five times as big. The CSO data suggests that the increase in mobile app records regarding tourist attractions might also be caused by the significant rise in the number of tourists that started in 2014 (just like in the case of hotel records). This is even more evident when one considers that the increase in the number of monuments in Silesia is nowhere near to the proportion of the attraction database growth (the number of monuments has changed only by 11%). This development in mobile app use was probably also not caused by an increase in museum interest since the number of visitors over the last five years followed no clear trend. The obtained data can be also investigated from the perspective of the share of each city in the total results found. The average number of hotels, restaurants and tourist attractions in all of the analyzed applications was calculated for each city.

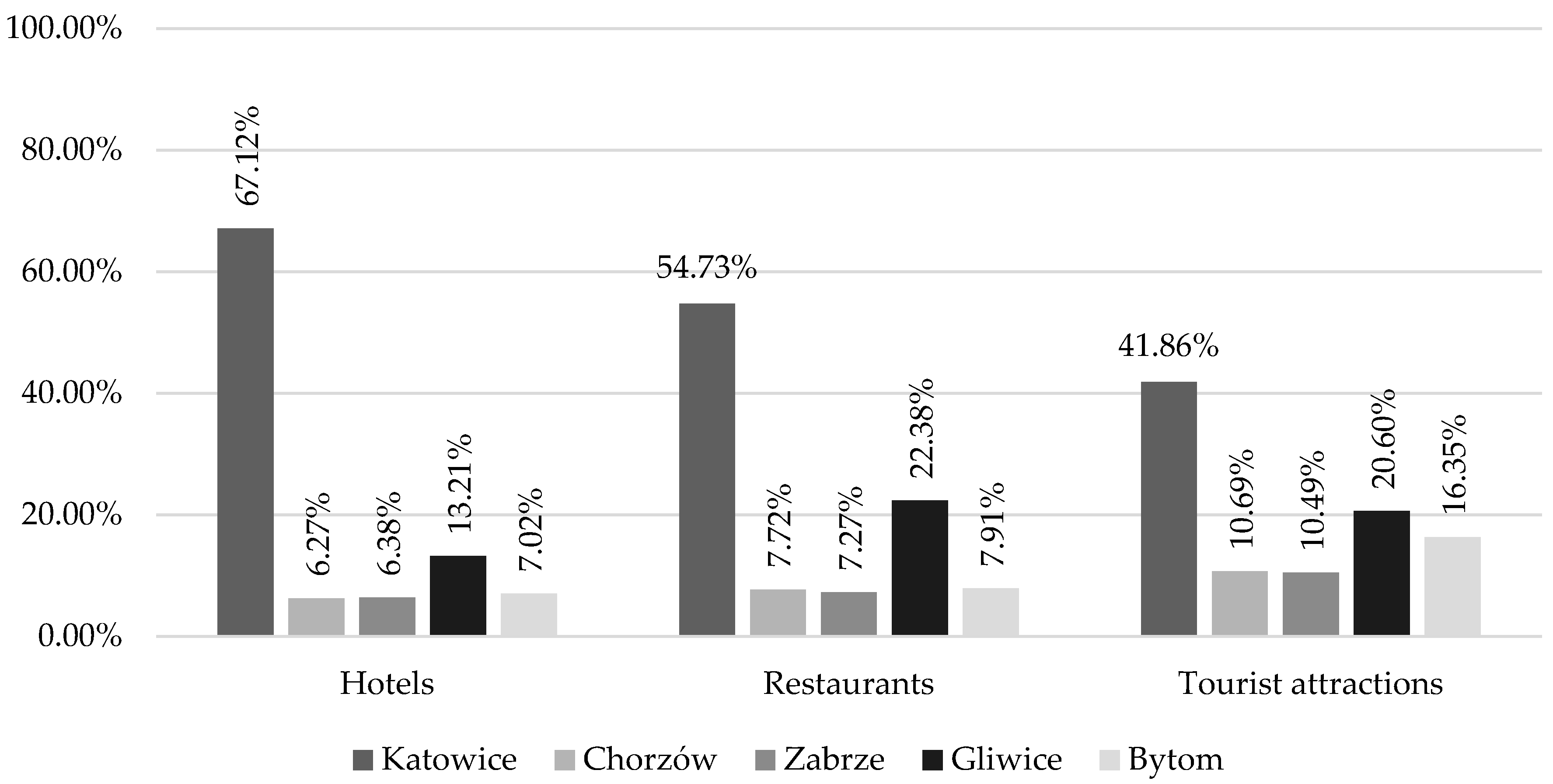

Figure 6 presents a graph illustrating the share of individual cities in the overall average values for each category.

The presented data shows that the largest share of objects found in each category falls on Katowice. The second destination for which the analyzed applications found the most results was Gliwice. In other cities, the results in each category were similar. This shows that tourists visiting the Upper Silesian Industrial District using mobile applications will find, primarily, attractions, accommodation and restaurants in the capital of the Silesian Voivodeship.

5. Discussion

Based on the research results presented, several observations can be made. The first one is to note the high dynamics of the mobile application market targeted at tourists. Over the past four years, out of 14 applications analyzed, two ended their activities (EloMaps and Worldmate), and another two were transformed to fulfill a new, different function (TouristEye and TripCase). In addition, three of them (Airbnb, Booking, Triposo), did not function or did not gain their nowadays popularity back in 2015. This shows how dynamically the business models in tourism change, and adapt to changing conditions on the market.

For every functionality that was unchanged during the four year research period, some level of development was noted; hotel, restaurant, and tourist attraction databases contain more records than in the past (in many cases multiple increases).

In addition, it seems interesting that one of the most popular tourist applications in the world, TripAdvisor, offering comprehensive functionality of finding all three types of facilities, has relatively seen a small number of accommodation facilities in its database (compared to Booking.com and Airbnb). One can make a recommendation here to take action in this matter and undertake some programs that encourage Silesian hoteliers to post their facilities on this site.

In terms of the number of tourist attractions found, Polska Niezwykła leaves all other services behind (more than twice as many objects as in any other application). Unfortunately, this rich collection of entries is currently only available in the Polish language. It can be assumed that if the developers of this application added an interface and descriptions in English, it would effectively increase the group of its users, and at the same time, it would allow for more effective use of the tourist potential of Silesian region.

Generally speaking, the presented results show that significant development took place in the region of Upper Silesia in terms of adopting mobile technologies in tourism (or at least by marking the presence of the most important points of interest for tourists in existing services). As it goes for the restaurants and hotels, those are private businesses. One can expect that when more attractions will be present in apps for foreigners, the demand for those private services will increase and drive the managers and owners into advertising their businesses more extensively in apps for English speakers; hence, their presence in the most popular apps should grow. However, as mentioned before, this an expected outcome of increasing the number of tourist attractions available through mobile apps. Since a large portion of these are part of the public sector (government, voivodeship, town hall, etc.) it lays in its competence to develop programs that would support and encourage these entities to mark their presence in mobile applications—as part of nowadays very intensively executed promotional programs for the voivodeship. Achieving a stage where a significant number of touristic sites are available for smartphone users, both domestic and foreigner tourists, would be the first step in adopting the smart tourism concept in the Silesian metropolis, and more elements of it could consistently be added.

The development of tourists’ uses of mobile apps and extend in their database records can be explained by the increasing number of tourists visiting Silesia. Since 2013, the number of tourist overnight stays has been constantly growing (from 4.6 M to 6.3 M in 2018). This shows that both the campaigns promoting Silesia as a touristic region and the start of adapting industrial heritage into touristic assets (since the IMR was created) have brought measurable effects. Upper Silesia, with its Industrial Monuments Route and sites on the UNESCO List, is heading in the direction of becoming an international industrial heritage tourism region, following the example of Ruhr region in Germany.

In terms of sustainable development of the Silesian region, the findings show that there is still a lot of space for improvements. The large disproportions between results from domestic apps and those for English-speaking users, that allow to find tourist attractions, indicate that the managers of touristic sites in Silesia might not be fully aware of the interconnections between all entities in a region, their role in international tourism, and how it is important for achieving sustainable development goals for the region, as well as for preserving heritage that is the core that attracts tourists to their business. They rather take the individual perspective, focusing on present customers and not on what causes them to be there, ignoring the big picture. This indication lays a path for further research in this area, and it might be beneficial for decision-making authorities to know the motivation of touristic sites runners and their awareness of their role in sustainable tourism. In the area of night’s lodging and gastronomy, things look differently. The results from international apps showed that their databases are better suited for tourists from any part of the world.

The overall increase in database records shows the increasing interest in mobile apps among tourists and their meaning for them. This can be also interpreted as proof that mobile apps are not just a temporary phenomenon, but rather, they have become a permanent element of it. Therefore, they should be taken into consideration while making sustainable development plans for touristic sites and regions, i.e., by incorporating the smart tourism concept. This also implies that businesses that focus on supporting mobile solutions, and advertise themselves in them, incorporate these technologies into their business models. When a model like this proves to be successful, it is expected that it will be replicated and applied by other entities, and the readiness to adopt the smart tourism concept in Silesia should continue to increase.

The research also showed that there is a large disproportion between the number of touristic sites figuring in mobile apps in Katowice and all other cities. This is mostly due to the fact that Katowice is the capital of the Silesian Voivodeship, and acts as a communication node for this southern part of Poland, as many national and international train connections and flights start or end in this city. Therefore, the portion of temporary international visitors is much higher in this city, and the demand for an offer for global customers is higher. It would be in the spirit of sustainability if future development plans for this region would include projects for better communication and promotion of attractions in neighboring cities, that are based on cultural heritage, in order to provide sufficient interest in it so they do not become a subject of degradation.

6. Concluding Insights and Future Research

There are some limitations to this research. First of all, it was concerning only one region, with a specific type of tourism standing out—industrial heritage tourism. The touristic function in this region is still developing, as it is a former heavy industry district, where the transformation to a post-industrial economy is still in progress. Things might be very different in other parts of the country, where tourism has been developing for much longer (i.e., the city of Cracow, Warsaw, etc.). Furthermore, we limited our research to a certain part of the whole voivodeship. We focused on the Upper Silesian Metropolitan area since it is the main region where industrial tourism occurs. The statistical data provided by the CSO, as well as results that concern the whole voivodeship, can distort the real picture of industrial heritage tourism in this area since the southern part of Silesia has few characteristic features: it shares borders with the Czech Republic and it has many mountain resorts in the Beskids area. Moreover, the north part of the Silesian Voivodeship is a significant religious center in Częstochowa. These features draw different types of tourists to this region, other than industrial heritage tourists, making it hard to distinguish which type of tourism had more impact on certain effects or touristic indicators. Therefore, one can consider the fact that we focused on a specific type of tourism as another limiting factor. Industrial heritage that is used in tourism already is mainly concentrated in selected parts of the world or a country. In Europe, it can be mainly found in southern Poland, north-west Germany, some regions in France, Belgium, and various parts of the UK. Therefore the results and conclusions that we draw can be especially useful for those regions, or for regions that have the potential to become an industrial heritage region (like, for example, parts of Ukraine or Russia). Another limitation is that in our research, we focused mainly on one element of smart tourism, which is m-tourism, by selecting the most popular international and domestic touristic applications for smartphones. This did not include other types of applications that might be utilized in tourist attractions (like general VR, AR, QR code apps, etc.), or technologies that are offered or are supported by mobile devices (tracking, traffic analysis or gathering of big data).

Further analogous research carried out at a similar time interval (or shorter, e.g., annually) would allow a more accurate understanding of the phenomenon of m-tourism development in the Silesian region and the use of modern technologies by local tourism service providers. There is also a need to research and assess the readiness of the entire region to adopt the smart tourism concept regarding technical infrastructure, available systems, the degree to which ICTs and other technologies are already in use in Silesian tourist sites, and the willingness of public and private tourist sites to participate and adopt this approach. Such findings, combined with previous ones, could potentially be used to build a framerate, a model or a set of guidelines for cities, metropolitan areas or regions that could make the process of becoming a smart tourism destination more efficient and effective.

The obtained results could also be used for other types of research. First of all, future research in the Silesian Region could focus on comparing statistical data gathered over the last years with data from other, more developed touristic regions. Such comparison would allow one to assess the development rate in comparison to other regions and find potential areas of improvement, avoiding mistakes or applying solutions for issues that have already been solved elsewhere. Secondly, the data could be used to compare it with results from other regions that are, at the same or earlier, at the touristic development stage, in order to identify development trends and patterns that are characteristic for them. Having such a reference point, future destinations could use it for benchmarking and monitoring their own development.

The conclusion that can be drawn from the obtained results, and that would apply to many other touristic regions, is that since a large portion of heritage all over the world is financed and governed by the public sector, it lacks elasticity in adapting to change and new conditions (more tourists overall and a bigger demand for foreigner orientated services). Our results show that the response to the increasing number of tourists visiting the analyzed region was much more intense from the private sector (hotels and restaurants) than the public one (the majority of tourist attractions based on heritage are governed by the state or city). This reveals itself when one notices that the changes in database records regarding tourist attractions for international travelers are much smaller in comparison with hotel and gastronomy records. Meaning that, in the course of the last four years, many hotels and restaurant owners added their objects into the databases of global-ranged apps, responding to the demand of international tourists, while most of the tourist attractions are still mainly findable in apps dedicated only for Polish speaking users.

Other regions and local authorities can learn from the Silesian case, and while formulating development plans they should focus on two things. The first one is to use tourism as part of sustainable development that protects and preserves heritage in its most possible unchanged form for future generations; keeping in mind that smart tourism is not a temporary trend but rather the future form of tourism. Therefore, the future success of a tourist destination and its heritage faith depends on how fast and well a region can adopt this concept. The second thing is that while adopting the smart tourism concept, one should mainly concentrate on the public sector, which is more inertive to change because it functions and is financed differently than private entities, which need to adapt immediately to the changes in supply and demand and will do it by themselves.