Coexistence with Bears in Romania: A Local Community Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

- 8 points if aggression was directed towards the interviewee;

- 6 points if there was aggression towards a person in the interviewee’s family;

- 3 points if a bear entered a household and attacked livestock;

- 2 points if the animal entered a shepherd’s camp and attacked the sheep/cows;

- 1 point if planted crops were damaged;

- 0 points if an interviewee declared a lack of experience or did not answer.

- 2 points if the subject had heard that those having the experience “had suffered” (based on the principle of empathy, e.g., “I suffer because others have also suffered”);

- 0 points if the subject has not recorded any consequence of the experience (conflict).

- 2 points if the subject has heard that those involved in the conflict had suffered;

- 1 point if the subject reports that sometimes people suffered, while at other times they did not;

- 0 points if the subject does not remember if people have suffered.

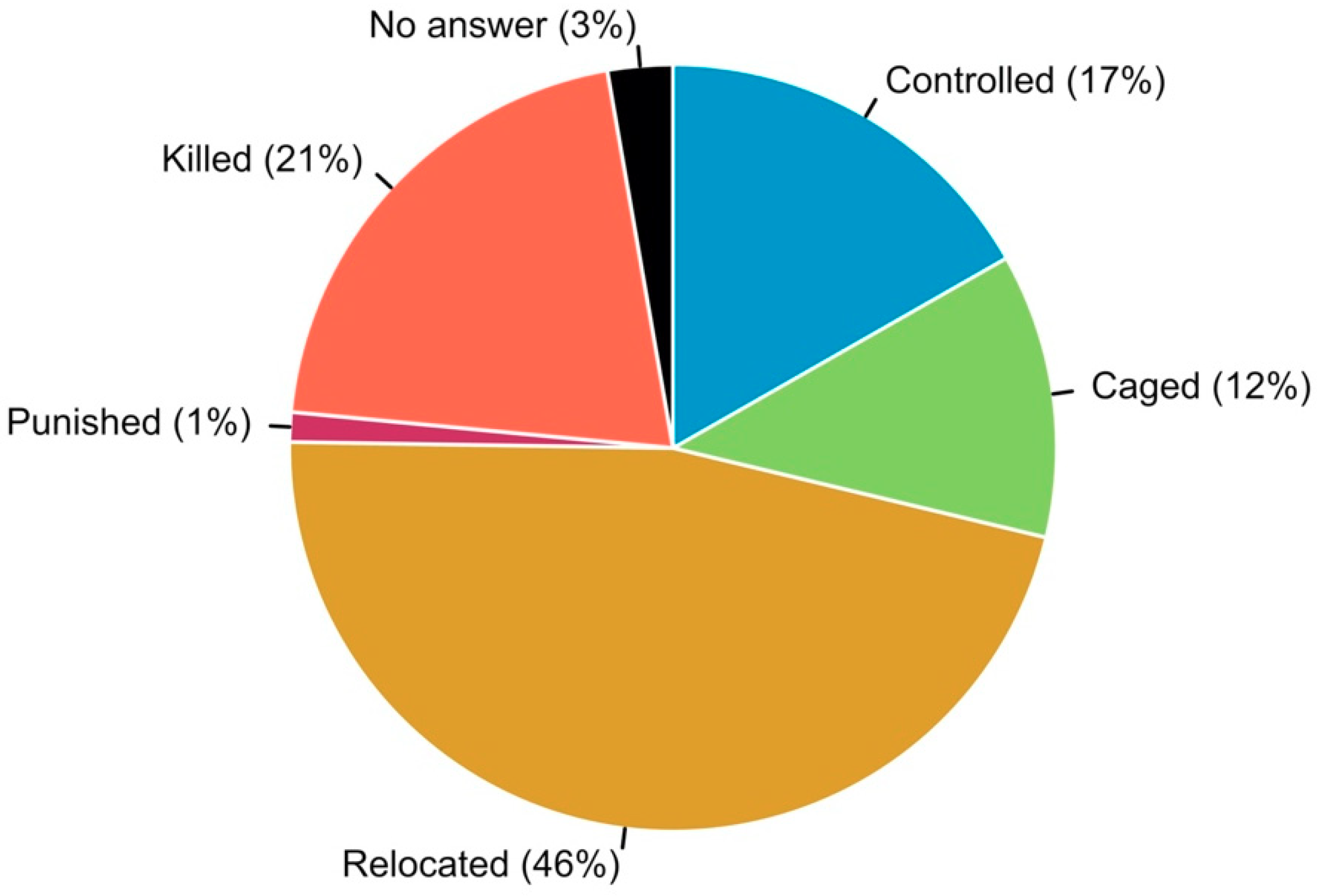

- (1)

- to be tracked down and killed immediately (associated to an extreme intolerance type; exclusion of the one that has a different behavior than the one desired);

- (2)

- to be caught and relocated far away from human settlements (associated to an isolation intolerance type);

- (3)

- to be caught and made to suffer so it would not come back again (associated to an average intolerance type);

- (4)

- to be caught and put in a zoo (associated to an indifference tolerance type);

- (5)

- to be caught and fit with a GPS collar to allow permanent monitoring of his position and presence (associated to a generosity tolerance type).

3. Results

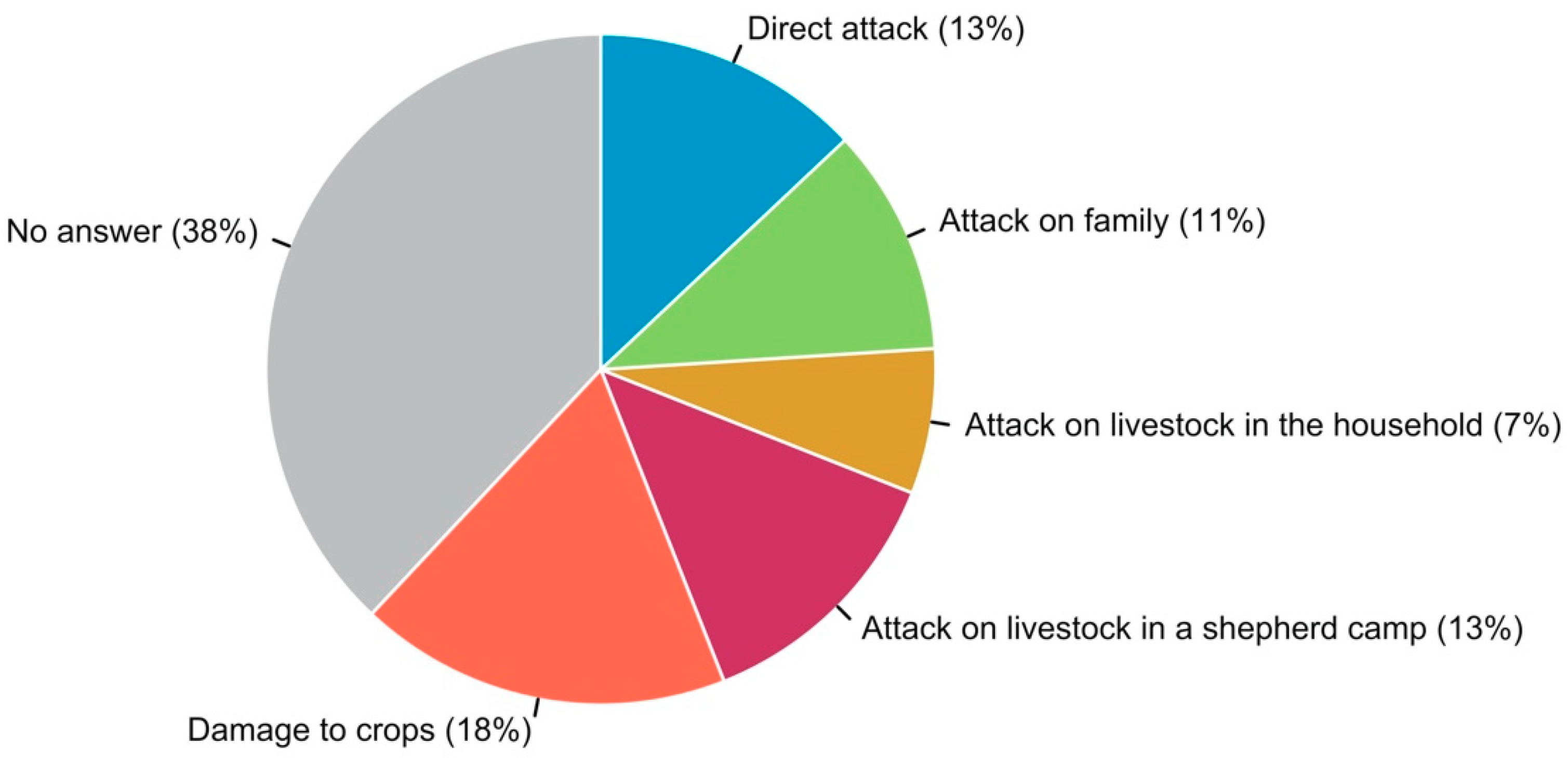

3.1. The Human–Bear Interaction

3.2. The Expressed Tolerance

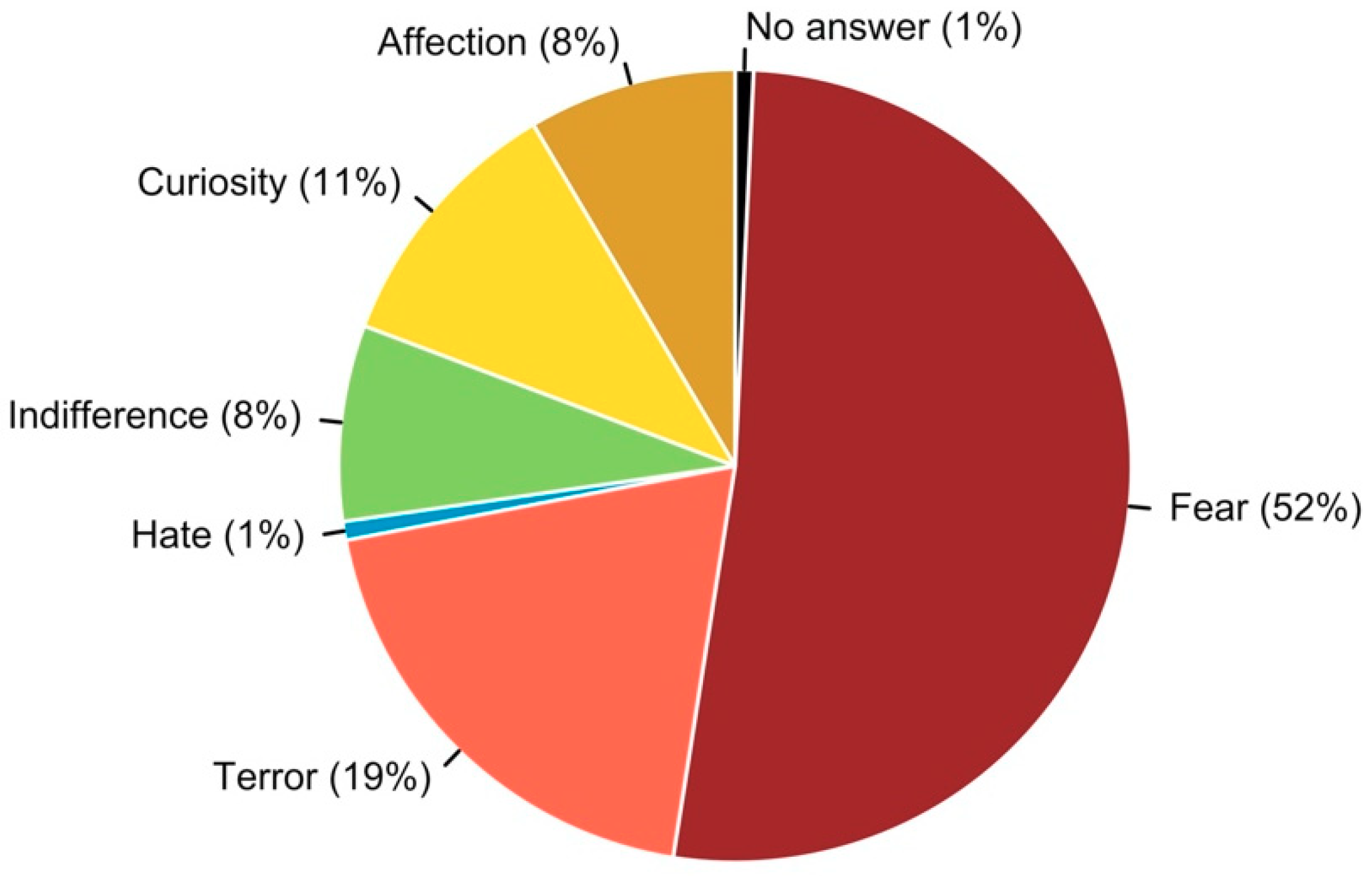

3.3. The Experienced Emotions

4. Discussion

4.1. Interaction with Bears: Mutualism or Competition

4.2. The Importance of Intangible Costs

4.3. The Coexistence Compromise

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fischer, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Landscape modification and habitat fragmentation: A synthesis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007, 16, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, K.L. Stand structure and growing space efficiency following thinning in an even-aged Douglas-fir stand. Can. J. For. Res. 1988, 18, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.H.; Linnell, J.D.C. Co-Adaptation Is Key to Coexisting with Large Carnivores. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teel, T.L.; Manfredo, M.J.; Jensen, F.S.; Buijs, A.E.; Fischer, A.; Riepe, C.; Arlinghaus, R.; Jacobs, M.H. Understanding the cognitive basis for human-wildlife relationships as a key to successful protected-area management. Int. J. Sociol. 2010, 40, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaske, J.J.; Roemer, J.M.; Taylor, J.G. Situational and emotional influences on the acceptability of wolf management actions in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2013, 37, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, S.; Barua, M.; Beinart, W.; Dickman, A.; Holmes, G.; Lorimer, J.; Loveridge, A.J.; Macdonald, D.W.; Marvin, G.; Redpath, S.; et al. An interdisciplinary review of current and future approaches to improving human-predator relations. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, C.K.; Ericsson, G.; Heberlein, T.A. A quantitative summary of attitudes toward wolves and their reintroduction (1972–2000). Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2002, 30, 575–584. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M. Rurality and collective attitude effects on wolf policy. Sustainability 2016, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, L. No place for predators? PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.G.; Woodroffe, R. Behaviour of carnivores in controlled and exploited populations. In Carnivore Conservation; Gittleman, J.L., Funk, S.M., MacDonald, D.W., Wayne, R.K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, D.J. Human Impacts on Bear Habitat Use. Bears Their Biol. Manag. 1990, 8, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodroffe, R.; Ginsberg, J.R. Edge effects and the extinction of populations inside protected areas. Science 1998, 280, 2126–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chapron, G.; Kaczensky, P.; Linnell, J.D.C.; von Arx, M.; Huber, D.; Andrén, H.; López-Bao, J.V.; Adamec, M.; Álvares, F.; Anders, O.; et al. Recovery of large carnivores in Europe’s modern human-dominated landscapes. Science 2014, 346, 1517–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Laundré, J.W.; Hernández, L.; Altendorf, K.B. Wolves, elk, and bison: Reestablishing the “landscape of fear” in Yellowstone National Park, U.S.A. Can. J. Zool. 2001, 79, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodberg-Holm, H.K.; Gelink, H.W.; Hertel, A.G.; Swenson, J.E.; Domevscik, M.; Steyaert, S.M.J.G. A human-induced landscape of fear influences foraging behavior of brown bears. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2019, 35, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Støen, O.-G.; Ordiz, A.; Evans, A.L.; Laske, T.G.; Kindberg, J.; Fröbert, O.; Swenson, J.E.; Arnemo, J.M. Physiological evidence for a human-induced landscape of fear in brown bears (Ursus arctos). Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kansky, R.; Knight, A. Key factors driving attitudes towards large mammals in conflict with humans. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 179, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapron, G.; López-Bao, J.V. Coexistence with Large Carnivores Informed by Community Ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inventarul Forestier National. Available online: http://www.roifn.ro (accessed on 5 July 2019).

- Ordinul nr. 625/2018 privind aprobarea Planului naţional de acţiune pentru conservarea populaţiei de urs brun din România. Law 625/2018, 2018. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/gi4domzvgy4a/ordinul-nr-625-2018-privind-aprobarea-planului-national-de-actiune-pentru-conservarea-populatiei-de-urs-brun-din-romania (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Decretul nr. 76/1953 cu privire la economia vânatului şi pescuitului în apele de munte. Decree 76/1953, 1953. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/heydemrtgy/decretul-nr-76-1953-cu-privire-la-economia-vanatului-si-pescuitului-in-apele-de-munte (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Legea nr. 26/1976 privind economia vînatului si vînătoarea. Law 26/1976, 1976. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/he2tknru/legea-nr-26-1976-privind-economia-vinatului-si-vinatoarea (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Legea fondului cinegetic şi a protecţiei vânatului nr. 103/1996. Law 103/1996, 1996. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/ge3demzq/legea-fondului-cinegetic-si-a-protectiei-vanatului-nr-103-1996 (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Legea vânătorii şi a protecţiei fondului cinegetic nr. 407/2006. Law 407/2006, 2006. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/geydamjsgq/legea-vanatorii-si-a-protectiei-fondului-cinegetic-nr-407-2006 (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Ordonanţa de urgenţă nr. 57/2007 privind regimul ariilor naturale protejate, conservarea habitatelor naturale, a florei şi faunei sălbatice. Government Emergency Ordinance 57/2007, 2007. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/geydqobuge/ordonanta-de-urgenta-nr-57-2007-privind-regimul-ariilor-naturale-protejate-conservarea-habitatelor-naturale-a-florei-si-faunei-salbatice (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Merriam Webster. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Schachter, S.; Singer, J. Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol. Rev. 1962, 69, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutchik, R. Emotions and Life: Perspectives from Psychology, Biology, and Evolution; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, H.R.B. Analysis of ordinal data with cumulative link models-estimation with the R-package ordinal. Available online: https://mran.microsoft.com/snapshot/2015-03-04/web/packages/ordinal/vignettes/clm_intro.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Christensen, H.R.B. Package “ordinal”: Regression Models for Ordinal Data. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ordinal/ordinal.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Hervé, M. Package “RVAideMemoire”: Testing and Plotting Procedures for Biostatistics 2019. Available online: https://rdrr.io/cran/RVAideMemoire/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- West, S.A.; Griffin, A.S.; Gardner, A. Social semantics: Altruism, cooperation, mutualism, strong reciprocity and group selection. J. Evol. Biol. 2007, 20, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begon, M.; Townsend, C.R.; Harper, J.L. Ecology: From Individuals to Ecosystems, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczensky, P.; Blazic, M.; Gossow, H. Public attitudes towards brown bears (Ursus arctos) in Slovenia. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 118, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majić, A.; Marino Taussig de Bodonia, A.; Huber, Đ.; Bunnefeld, N. Dynamics of public attitudes toward bears and the role of bear hunting in Croatia. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 3018–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enserink, M.; Vogel, G. Wildlife conservation. The carnivore comeback. Science 2006, 314, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressel, S.; Sandström, C.; Ericsson, G. A meta-analysis of studies on attitudes toward bears and wolves across Europe 1976–2012. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, G. Protection, politics and protest: Understanding resistance to conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 184–201. [Google Scholar]

- von Essen, E.; Hansen, H.P.; Nordström Källström, H.; Peterson, M.N.; Peterson, T.R. The radicalisation of rural resistance: How hunting counterpublics in the Nordic countries contribute to illegal hunting. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 39, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ordiz, A.; Bischof, R.; Swenson, J.E. Saving large carnivores, but losing the apex predator? Biol. Conserv. 2013, 168, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Penteriani, V.; López-Bao, J.V.; Bettega, C.; Dalerum, F.; del Mar Delgado, M.; Jerina, K.; Kojola, I.; Krofel, M.; Ordiz, A. Consequences of brown bear viewing tourism: A review. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swenson, J.E. Does hunting affect the behavior of brown bears in Eurasia? Ursus 1999, 11, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Treves, A.; Karanth, K.U. Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijper, D.P.J. Lack of natural control mechanisms increases wildlife–forestry conflict in managed temperate European forest systems. Eur. J. For. Res. 2011, 130, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Interaction Type | Emotional Intensity Level | Added Weight | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No interaction (initial score 0) | Absent | 0 | 0 | |

| With interaction | impersonal mediated (initial score 1) | Absent | 0 | 1 |

| Medium | 1 | 2 | ||

| High | 2 | 3 | ||

| personal mediated (initial score 3) | Absent | 0 | 3 | |

| High | 2 | 5 | ||

| direct (initial score 5) | Absent | 0 | 5 | |

| Low (crops destruction) | 1 | 6 | ||

| Medium (attack on livestock at shepherd camp) | 2 | 7 | ||

| Relatively high (attack on livestock in the household) | 3 | 8 | ||

| High (aggressed relatives) | 6 | 11 | ||

| Very High (aggressed subject) | 8 | 13 | ||

| Interaction Type | Description | Cases Reported | |

|---|---|---|---|

| no. | % | ||

| Personal direct interaction (approx. 20% of total sample) | Missing description | 30 | 38 |

| Crops destruction | 14 | 18 | |

| Livestock destruction in shepherd camp | 10 | 13 | |

| Livestock destruction in household | 6 | 7 | |

| Aggression on relatives | 9 | 11 | |

| Aggression on the subject | 10 | 13 | |

| TOTAL | 79 | 100 | |

| Personal mediated interaction (approx. 36% of total sample) | People suffered | 95 | 66 |

| People did not suffer | 48 | 34 | |

| TOTAL | 143 | 100 | |

| Impersonal mediated interaction (approx. 84% of total sample) | People suffered | 235 | 71 |

| Sometimes yes, sometimes no | 58 | 17 | |

| People did not suffer | 40 | 12 | |

| TOTAL | 333 | 100 | |

| Absent (10% of total sample) | No knowledge of interaction | 40 | 100 |

| TOTAL | 40 | 100 | |

| Type of Interaction | No. of Cases with “Kill” Option | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct interaction | direct aggression | 6 |

| aggression on family members | 1 | |

| attack on livestock in the household | 0 | |

| attack on livestock in the shepherd camp | 6 | |

| damage to crops | 4 | |

| no answer | 5 | |

| Total | 22 | |

| Indirect interaction | interpersonal | 2 |

| impersonal | 25 | |

| interpersonal & impersonal | 18 | |

| no answer | 16 | |

| Total | 61 | |

| Grand Total | 83 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stăncioiu, P.T.; Dutcă, I.; Bălăcescu, M.C.; Ungurean, Ș.V. Coexistence with Bears in Romania: A Local Community Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7167. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247167

Stăncioiu PT, Dutcă I, Bălăcescu MC, Ungurean ȘV. Coexistence with Bears in Romania: A Local Community Perspective. Sustainability. 2019; 11(24):7167. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247167

Chicago/Turabian StyleStăncioiu, Petru Tudor, Ioan Dutcă, Marian Cristian Bălăcescu, and Ștefan Vasile Ungurean. 2019. "Coexistence with Bears in Romania: A Local Community Perspective" Sustainability 11, no. 24: 7167. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247167

APA StyleStăncioiu, P. T., Dutcă, I., Bălăcescu, M. C., & Ungurean, Ș. V. (2019). Coexistence with Bears in Romania: A Local Community Perspective. Sustainability, 11(24), 7167. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247167