How Can Street Art Have Economic Value?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Street Art and Impacts on the Property Market: an Overview

2.1. Street Art and the Property Market

2.2. How Can the Impacts of Street Art on Real Estate Prices be Measured?

- a determination of the price change (ΔPKji = 1, 2, ..., c′j) that produces environmental modification on the properties of the sample;

- the aggregation of the price change (ΔPj) in each property category;

- the determination of the monetary value of environmental externalities (We).

3. Street Art and Socio-Economic Dynamics in the Metropolitan City of Naples

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bengtsen, P. The Street Art World; Almendros de Granada Press: Lund, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blanché, U. Street Art and related terms—Discussion and working definition. SAUC-Street Art Urban Creat. Sci. J. 2015, 1, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, A. Sustainable Cities or Sustainable Urbanization. UCL’s J. Sustain. Cities 2009. Available online: www.ucl.ac.uk/sustainable-cities (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Camorrino, A. Vedi Napoli e poi muori. La Street Art dal punto di vista della sociologia della cultura. In Società, Economia e Spazio a Napoli; Punziano, G., Ed.; Working Paper No. 28; GSSI Social Sciences: Naples, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Markusen, A.; Gadwa, A. Creative Placemaking, Markusen Economic Research Services and Metris Arts Consulting; National Endowment for the Arts: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mural Arts Philadelphia. Annual Report. 2018. Available online: www.muralarts.org (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Stern, M.J.; Seifert, S.C. An Assessment of Community impact of the Philadelphia, Department of Recreation Mural Arts Program. In Social Impacts of the Art Projects; School of Social Work, University of Pennsylvania, Penn Libraries: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Planning PhotographyCom@UrbanImagist, Urban Street Art: Fostering Innovation in Cities. 2018. Available online: www.smartcitiesdive.com (accessed on 14 July 2014).

- Floch, Y. Street Artists in Europe; Study paper; European Parliament, Policy Department, Structural and Cohesion Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jazdzewska, I. Murals as tourist attraction in a post-industrial city: A case study of Lodz, Poland. Tourism 2017, 27, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- A.N.C.I. Street Art. L’avvio di Lavori Del Primo Tavolo Di Esperti Per Un Programma Di Valorizzazione Nazionale Nei Comuni D’italia, 23-11-2016. Available online: www.anci.it (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Zerlenga, O.; Forte, F.; Lauda, L. Street Art in Naples in the territory of the 8th Municipality. In Graphic Imprints, Proceedings of the International Congress of Graphic Design in Architecture, EGA 2018; Carlos, L.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kauko, T. Pricing and Sustainability of Urban Real Estate; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kauko, T. Innovation in urban real estate: The role of sustainability. Prop. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T. Urban Regeneration and Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities; RICS Research; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Markusen, A.; Gadwa, A. Arts and culture in urban or regional planning: A review and research agenda. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2010, 29, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicario, L.; Martinez Monje, P.M. Another ‘Guggenheim effect’? The generation of a potentially gentrifiable neighbourhood in Bilbao. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 2383–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, S.; Coaffee, J. Art, gentrification and regeneration: From artist as pioneer to public arts. Eur. J. Hous. Policy 2005, 5, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodach, C.; Foster, N.; Murdoch, J. Gentrification and the artistic dividend: The role of the arts in neighborhood change. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2014, 80, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currid, E. The Warhol Economy: How Fashion, Art and Music Drive New York City; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Seresinhe, C.L.; Preis, T.; Moat, H.S. Quantifying the link between art and property prices in urban neighborhoods. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flickr. Available online: www.flickr.com (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Warner, L. How much would you pay to live in an Bansky house? Property Report. 29 September 2017. Available online: https://www.propertyreporter.co.uk/property/how-much-would-you-pay-to-live-in-a-banksy-house.html (accessed on 8 January 2019).

- Martinique, E. What is the Effect of Street Art on Real Estate Prices? Widewall. 30 May 2016. Available online: https://www.widewalls.ch/street-art-real-estate/ (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Il Sole 24 Ore. Daily Newspaper. Available online: www.ilsole24ore.com/art/arteconomy/2012-01-12/l-arte-strada-rivaluta-muri-073802.shtml?uuid=AazR35cE (accessed on 8 January 2019).

- Italian Agency of Revenue. Available online: www.agenziaentrate.gov.it (accessed on 1 July 2018).

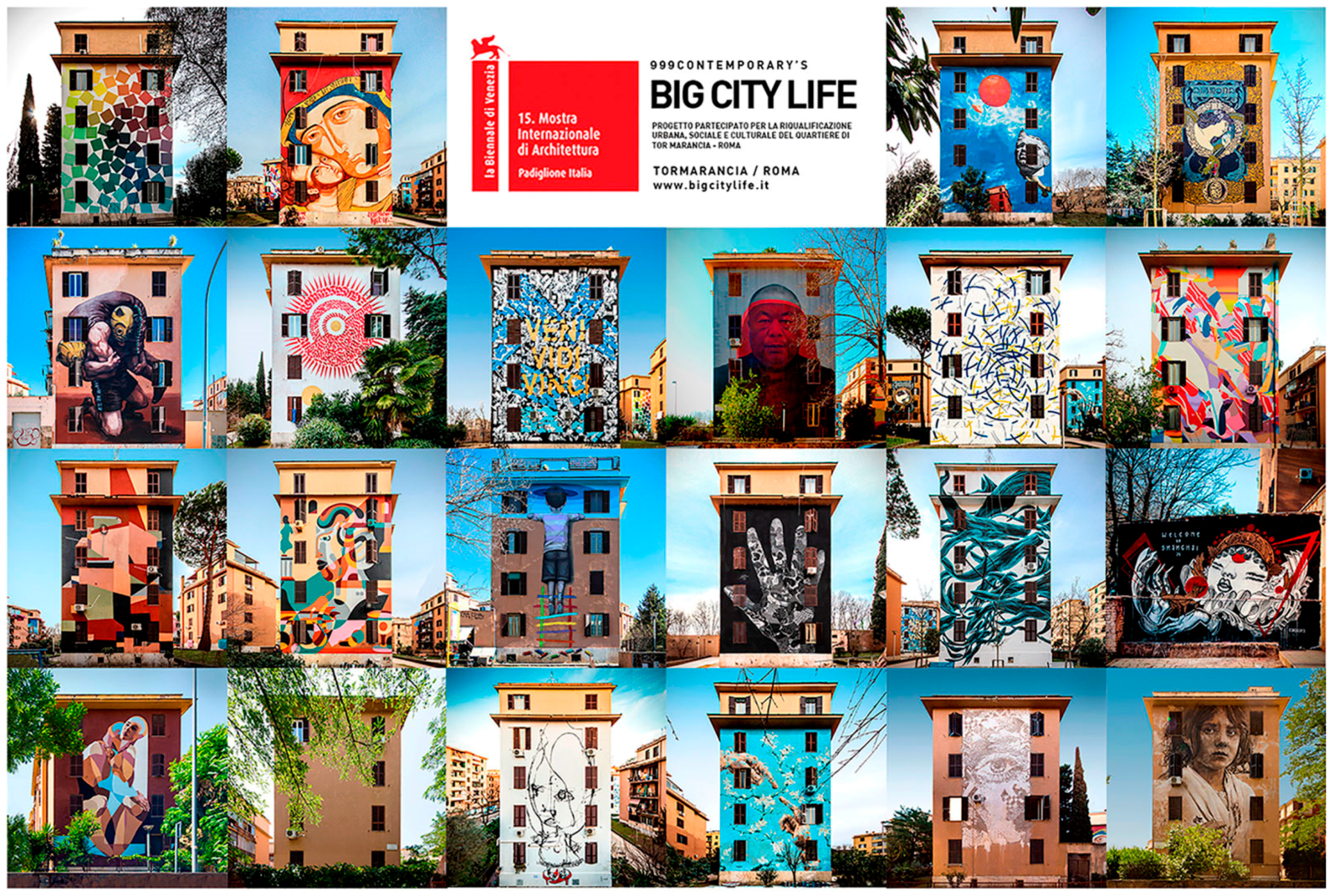

- 999 Contemporary. Available online: www.bigcitylife.it (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Del Giudice, V.; De Paola, P.; Manganelli, B.; Forte, F. The monetary valuation of environmental externalities through the analysis of real estate prices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, V.; De Paola, P.; Torrieri, F. An integrated choice model for the evaluation of urban sustainable renewal scenarios. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1030–1032, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Napoli. Disciplinare per L’autorizzazione All’utilizzo di Superfici Pubbliche per la Creatività Urbana; DISP/2016/0005488; Municipality of Naples: Naples, Italy, 7 December 2016.

- Forte, F.; Russo, Y. Evaluation of User Satisfaction in Public Residential Housing—A Case Study in the Outskirts of Naples, Italy. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; WMCAUS-IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; Volume 245, p. 052063. [Google Scholar]

- Park of the Murales. Available online: www.parcodeimurales.it (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Saaty, T.L.; De Paola, P. Rethinking Design and Urban Planning for the Cities of the Future. Buildings 2017, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, F.; Girard, L.F. Creativity and new architectural assets: The complex value of beauty. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 12, 160–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gressel, K. Public Art and the Challenges of the Evaluation, Createquity. 7 January 2012. Available online: www.createquity.com/2012/01/public-art-and-the-challenge-of-evaluation (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- IXIA, Public Art. A Guide to Evaluation. March 2010. Available online: http://ixia-info.com/research/evaluation (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Haedicke, S.C. Contemporary Street Arts in Europe—Aesthetics and Politics; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-137-29183-7. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forte, F.; De Paola, P. How Can Street Art Have Economic Value? Sustainability 2019, 11, 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030580

Forte F, De Paola P. How Can Street Art Have Economic Value? Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030580

Chicago/Turabian StyleForte, Fabiana, and Pierfrancesco De Paola. 2019. "How Can Street Art Have Economic Value?" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030580

APA StyleForte, F., & De Paola, P. (2019). How Can Street Art Have Economic Value? Sustainability, 11(3), 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030580