1. Introduction

While fish can be an important source of daily protein, omega-3 fatty acids, and other essential nutrients, fish may also contain contaminants, which are detrimental to human health [

1], particularly in self-caught fish from urban areas. Industrialization contributed to long histories of chemical contamination in urban settings, resulting in contaminants such as mercury, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and dioxins moving into aquatic food webs. Considerable effort was extended to inform the public of the benefits and risks of fish consumption at local, state, and international (United States and Canada) levels in order to improve conscious consumption of self-caught fish species. Fish consumption advisories or guidelines are designed to provide citizens with information on fish from local waters that are lower in chemical contamination and are, therefore, safe meal choices relative to those that are high in contamination, thus improving conscious consumption behaviors. However, advisories typically contain complicated information which is difficult to convey without indiscriminately discouraging fish consumption. Many populations can benefit from fish as a low-cost, readily available addition to their diet; avoidance of fish altogether reduces nutritional opportunities from fish low in contaminants, a problematic potential outcome [

2].

Improving the conscious consumption of game fish toward those low in contaminants can be challenging. Consumption guidelines originating from official or impersonal sources can be viewed with mistrust among anglers when compared to years of recreational experience with a resource [

3]. Particularly when there is generational and cultural value in a resource, willingness to alter consumption practices tends to be low. Such perceptions can lead anglers to disregard guidelines in favor of information disseminated within the fishing community or from other sources viewed as more inherently trustworthy [

4]. Implementation of guideline suggestions can be further complicated by the abundance of subsistence anglers in a given region. Individuals who engage in angling activities with consumption as a main goal may respond differently to advisories than anglers who catch and release [

5]. Similarly, in areas where poverty is high, the ability to alter one’s consumption practices may be limited. In these instances, the importance of game fish as a cost-effective food resource may outweigh the ability to consider consumption limitation.

Designing guidelines that adequately reach vulnerable anglers can be an additional challenge. Research suggests that, to achieve a change in behavior, educational approaches need to be tailored to the particular population and problem, and involve direct contact with anglers to be effective [

6,

7,

8]. The efficacy of advisory programs in improving consumption behaviors is variable and difficult to measure [

9]. Criticisms of advisory campaigns suggest that information does not often reach diverse groups of people, or even those groups who may be the most impacted by fish contamination. In particular, previous research showed that advisory information typically does not effectively reach minorities, women, people with low levels of educational attainment [

10], or immigrant communities [

11]. Further, while progress was made on assessing the impact of advisories, many of these studies primarily include anglers who are white and have moderate income and educational backgrounds [

12]. This problem is especially significant in distressed urban environments where anglers are more likely to engage in subsistence fishing due to high poverty rates. Studies also showed that a higher proportion of those who catch species high in contaminants, keep them, and share them with family and friends are people of color [

13,

14]. Frequent consumption of fish with high levels of contaminants can contribute to adverse health conditions especially for fetuses, children, and adults with existing chronic health issues such as heart, thyroid, or immune diseases [

15].

Residents of Detroit, Michigan commonly supplement their food supply with locally caught fish, which are available at low to no cost [

16]. These subsistence anglers are primarily low-income, minority individuals [

13] who regularly fish for white bass (

Morone chrysops) and walleye (

Sander vitreus), which are two of the more contaminated species in this area. As of the 2010 US Census [

17], one-third of Detroit residents live in poverty (more than twice the state average) and the median household income (

$29,447) was 60% below the state median. Additionally, Detroit had a 20% unemployment rate. Unfortunately, this suggests that the populations with the highest reliance on fish from the Detroit River as a food source are also those groups most difficult to target for educational and outreach efforts.

Due to possible environmental justice concerns associated with fish contaminant levels on the Detroit River, an intensive educational program was launched in 2010 to provide fish consumption guideline information in a targeted way to those individuals who were most susceptible and, thus, most likely to benefit from the information. As part of this program, multiple outreach methods were utilized in an attempt to have the largest impact on the shoreline angler population.

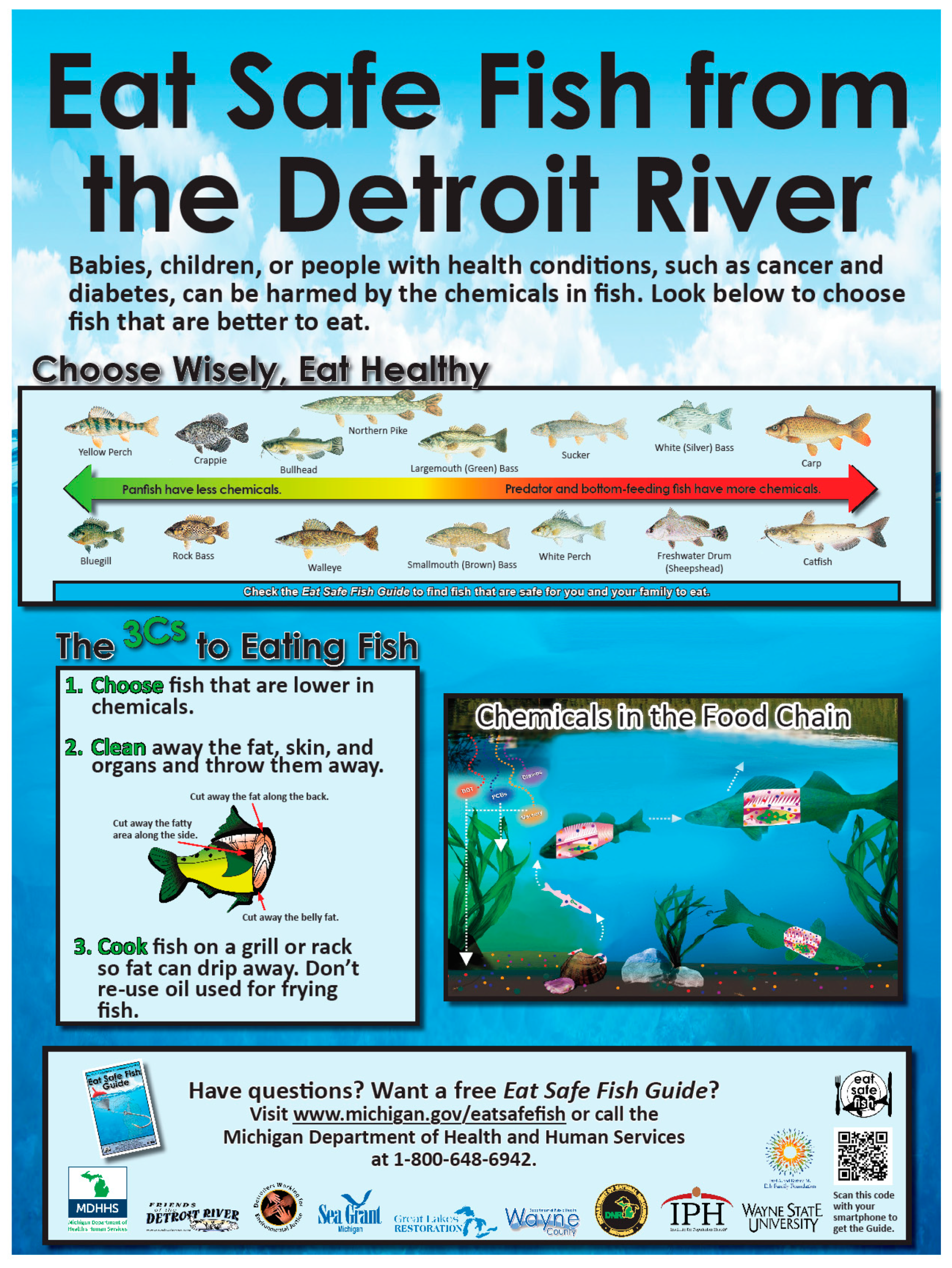

The first method was to have a permanent educational presence at fishing locations, through the installation of signs containing consumption guideline information (

Figure 1) along the Detroit River in 2010 (and updated in 2015) at 28 locations known to be popular shore-fishing access points (

Figure 2). Signs were designed in collaboration with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, community focus groups, and communication experts from Wayne State University, to provide information on contaminant levels in the various fish species in the Detroit River and provide guidance on the safest consumption practices. Local community focus groups were involved in evaluating both the signs and pamphlets during the design phase of these materials.

A second outreach method was designed to confront deep cultural preferences and people’s own interpretation of risk, which often hinder behavioral change. Social norms and community practices may intercede between effective interventions and adequate uptake into daily life [

18]. To overcome this challenge in information distribution, two to three Detroit residents were hired as River Walkers, beginning in 2012 and continuing through 2016, that assisted outreach efforts. By visiting shore-fishing sites and directly communicating with active anglers, River Walkers provided information on eating locally caught fish and offered hard copies of educational materials (a third outreach method). River Walkers were able to distribute materials including (1) an “Eat Safe Fish in the Detroit Area” pamphlet, (2) an “Eat Safe Fish Guidelines” educational pamphlet (3) a “Hooked on Fish from the Great Lakes” cookbook, (4) a fishing crossword puzzle and word search for children, and (5) temporary tattoos. This personal interaction with an informed, local individual provided an easy way for anglers to express concerns or get answers to their questions. It also provided a face to the consumption guideline campaign.

The overall objective of this study was to assess the progress, strengths, and weaknesses of the educational outreach program outlined above, which was designed to improve conscious consumption practices of fish caught from the Detroit River. Specifically, this study evaluated the overall awareness of fish consumption guidelines among anglers, their knowledge of the information provided by guidelines, which outreach methods were most effective in implementing changes in behavior, and potential environmental justice issues associated with the consumption guideline campaign itself (i.e., whether information equally reached all demographic subsets of anglers). An educational campaign with several methods of outreach including direct interaction with the most vulnerable anglers is relatively rare, and our assessment of its strengths and weaknesses presents a novel addition to fish consumption literature. Furthermore, as a multi-year study, this allows for the assessment of progress in information dissemination over time and adds insight into changing demographics and attitudes toward consumption advisories.

3. Results

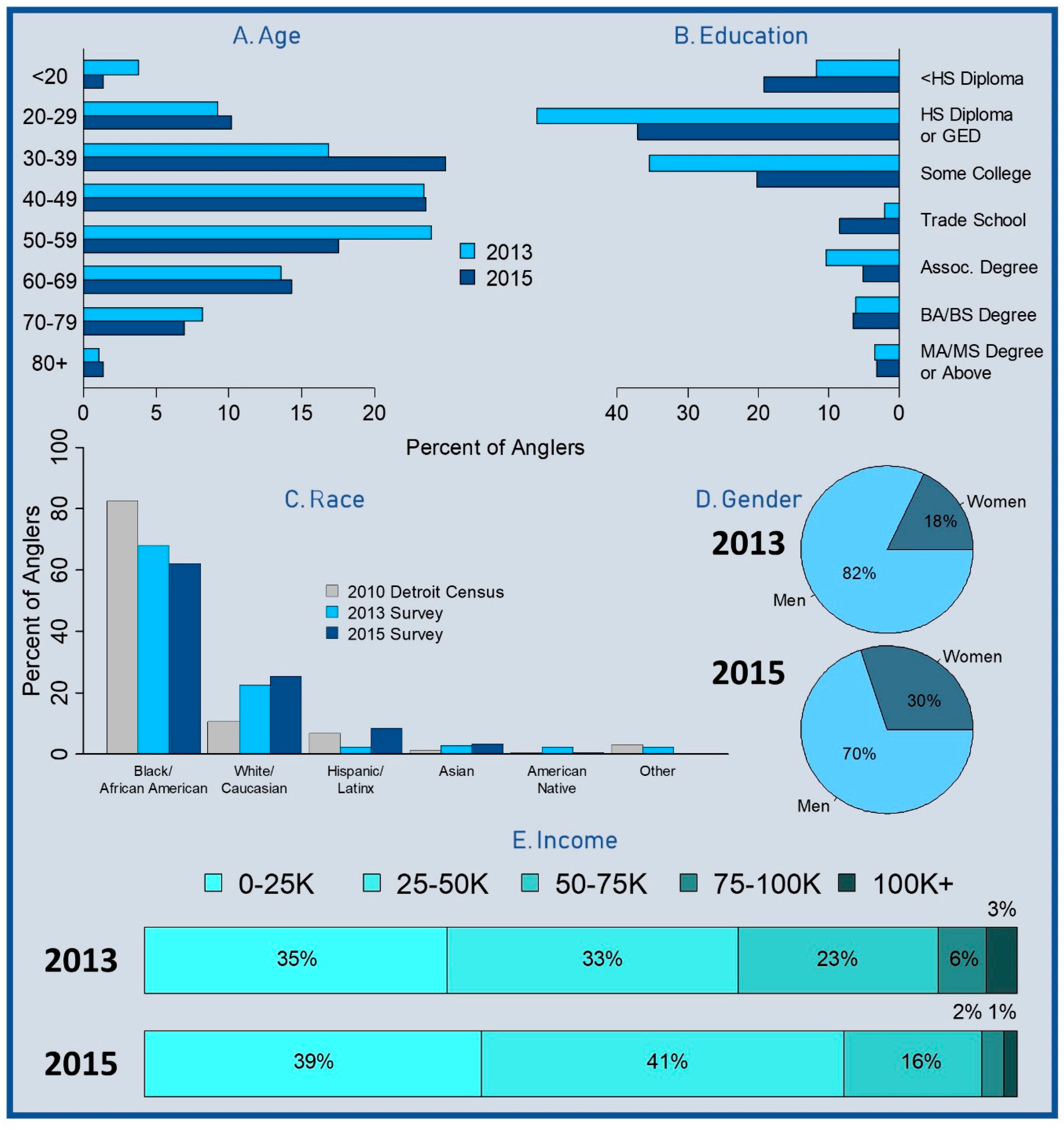

A total of 431 shoreline anglers were surveyed (200 in 2013 and 231 in 2015) (see

Supplementary Materials). The anglers represented 87 of 1160 Michigan zip codes and one Ohio zip code, most of which are located within 25 km of the Detroit River (

Figure 2). For each year, the majority of the survey participants self-identified as African American/Black (68% in 2013; 62% in 2015), with smaller proportions identifying as White/Caucasian, Asian/Pacific Islander, Arab/Middle Eastern, Hispanic/Latinx, American Indian or Alaskan native, or other (

Figure 3C). Most of the anglers surveyed were male (82% in 2013; 70% in 2015), though an increase in female anglers from 18% in 2013 to 30% in 2015 was observed (

Figure 3D). Anglers ranged in age from 18 to 85, with the largest proportion of anglers being in their 50s in 2013, and in their 30s in 2015 (

Figure 3A). In 2013, 34% of the surveyed anglers reported an annual household income less than

$25,000 with 34% reporting a household income in the range of

$25,000–

$49,999 and 32% reporting a household income higher than

$50,000 (

Figure 3E). Income ranges were similar in 2015 with 39% reporting an income less than

$25,000, 42% reporting a household income between

$25,000 and

$49,000, and 20% reporting an income greater than

$50,000 (

Figure 3E). In 2013, 10% of anglers had less than a high-school diploma, while 43% of anglers had received a high-school diploma or General Education Development (GED), and 48% had at least some college or post-high-school education (

Figure 3B). Similarly, in 2015, 19% had less than a high-school diploma, 37% had a high-school diploma or GED, and 44% of anglers had at least some post-high-school education (

Figure 3B).

3.1. Fish Consumption

Most anglers surveyed (77% in 2013 and 68% in 2015) reported that fish are at least somewhat important in their diets. In both survey years, anglers reported consuming the most fish in the summer and spring seasons, which coincide with typical spawning runs of most species. During this time, anglers were observed in the greatest numbers along the shoreline. The number of meals per week consumed by anglers was much higher in 2015 than 2013 (p < 0.001; X2 = 146.78). However, this difference may be due to the addition of serving size estimates included in the 2015 survey. Because a “serving size” may be different among individuals, the 2015 survey included a definition of “serving size” as being approximately the size of one’s hand. This would increase the total number of servings reported if those servings were generally multiple hand-sized portions, which were reported as a single serving in the 2013 survey. Our data show that the mean number of servings, as defined by a “hand-sized” serving of fish, consumed per week by the anglers in 2015 was 7.5 ± 0.25 in spring and 6.2 ± 0.25 in summer, or roughly one serving per day. Consumption fell to 0.99 ± 0.25 servings per week in the fall and 0.11 ± 0.26 in the winter, or less than one serving per week.

Anglers reported frequently providing fish to family and friends with 76% in 2013 and 69% in 2015 reporting giving fish away (

Figure 4A). Of that which is given away, 52–59% of anglers reported providing fish to children, 78–83% to women, and 61–92% to men (depending on survey year—

Figure 4B). Encouragingly, almost all anglers (94–98%) reported removing the head, skin, fat, and/or organs prior to cooking. In 2013, typical cooking methods were also addressed. Ninety percent of anglers regularly fried their fish (a cooking method not recommended due to its inability to eliminate fats containing PCBs and dioxins). Baking and grilling (recommended methods) were less common with only 34% and 21% of anglers, respectively, cooking their fish this way. Finally, fewer than 5% of anglers reported boiling, broiling, smoking, and/or steaming their catch.

White bass (

Morone chrysops; also locally referred to as silver bass or, occasionally, stripe bass) was the most common species taken home by anglers. Walleye (

Sander vitreus) was the next most common species followed by yellow perch (

Perca flavescens), smallmouth bass (

Micropterus dolomieu; locally brown bass), and catfish (typically channel catfish,

Ictalurus punctatus). Some differences were identified in the species anglers commonly took home between 2013 and 2015 (

Figure 5). Specifically, white bass, walleye, and smallmouth bass were all more commonly kept in 2015 than 2013 (

p = 0.003;

X2 = 39.28). Additionally, a larger diversity of species was kept in 2013 than 2015 (

H’ = 3.00 in 2013,

H’ = 2.33 in 2015). Species with higher restrictions (as indicated by the Eat Safe Fish program) were more commonly kept in 2015 than 2013 (

p = 0.021;

X2 = 9.70;

Figure 5). However, this trend was driven by an increase in walleye (46% to 72%) and white bass (75% to 90%), while consumption of catfish decreased (35% to 32%). Additionally, the mean timing of surveys was later in 2015 than in 2013 (

p < 0.001) by a mean of 6.21 Julian days (median difference of 16 Julian days), which may account for skewing of data toward a particular subset of species (as spawning runs for specific species are typically distinct events and attract a large number of anglers, particularly for white bass).

3.2. Consumption Guideline Awareness

By 2015, 74% of anglers who were aware of the guidelines understood there was a health risk associated with consuming chemicals in fish; similarly, 69% of anglers aware of the guidelines knew consumption of certain species of fish should be limited. During the two-year period between surveys, general awareness of the fish consumption guidelines did not change (55% in 2013, 57% in 2015; p = 0.766, X2 = 0.088). A larger proportion of anglers saw the signs and/or encountered the River Walkers in 2015 than 2013 (p = 0.005, X2 = 7.76; p < 0.001, X2 = 54.26). However, fewer people who saw the sign in 2015 actually read it (p = 0.011, X2 = 6.45), perhaps suggesting some decline in interest over time as people become accustomed to the signs the longer they are present. Demographic factors had little impact on anglers’ awareness of the guidelines, with race, income, and gender having insignificant correlation with angler awareness of the guidelines (p = 0.814, 0.198, and 0.149, respectively). However, education was correlated with awareness (p = 0.007); individuals with higher educational achievement (some college, trade school, or more) were more commonly aware of the guidelines (69%) than individuals with lower educational achievement (high school degree, GED, or less; 46%). Encouragingly, anglers who were aware of the guidelines were 5% more likely to supplement their diet with species lower in contaminants. Additionally, 36% of anglers shared information about the guidelines with friends or family, and 8% of anglers who were not aware of the advisory still had some knowledge about the risks of contaminants.

The different methods utilized in the study were differentially effective between years. The River Walkers, signs, and educational pamphlets were all reportedly more effective in 2013 than in 2015 (

Table 1). In 2013, all methods were reported as helpful to the anglers, with no significant differences for any pairwise comparison. Pamphlets had an influence on 51% of anglers in 2013, but this number fell to 13% in 2015. In 2015, the signs were reportedly more helpful to anglers than were the River Walkers. However, a higher percentage of anglers reported that the sign was confusing in 2015 than in 2013 (up from 15% to 23%). No correlation with race, education, or income was found with a positive response to any particular outreach method (

p = 0.119–0.955).

Anglers did report having implemented some behavioral changes due to consumption suggestions. The largest reported change was in the species consumed by anglers (29%). Cooking method (21%) and fishing method or location (9%) were also impacted by the consumption campaign (

Figure 6). Walleye and white bass were the most popular species consumed by all anglers, but those who reported having made changes to the species they consume were 40% more likely to supplement their diet with species with lower contamination levels in 2015. Education, income, and gender had no significant impact on changes in behavior. However, race was significantly correlated with reports of changes in species anglers chose to consume (

p = 0.002). Specifically, participants who self-identified as White/Caucasian were less likely to have changed the species they consumed than those who were Hispanic/Latinx (

p = 0.008), though the small sample sizes for all races other than African American/Black may have influenced this outcome. This trend was, thus, driven by African American/Black participants who reported changing the species they consume at a higher rate than other participants (34% as opposed to a combined 16% for all other participants).

4. Discussion

The history of contamination in Detroit and the surrounding area make understanding the relative benefits and risks of fish consumption difficult to grasp [

21]. Despite challenges in designing effective educational campaigns, methods tailored to the specific population of anglers as described in this study demonstrated gains in general knowledge among Detroit anglers. Following a multifaceted educational campaign that began in 2010, and included one-on-one interactions with anglers beginning in 2012, we were able to document awareness of fish consumption advisories by 2013, a period just three years after the start of the program. Anglers reported significant behavioral changes in the fish species they consumed by 2015. Despite awareness of the consumption guidelines not having changed over our two-year survey period, there were significant improvements in the conscious consumption of fish among Detroit anglers.

Contrary to previous findings [

26], African American/Black anglers were more likely to supplement their diet with lower-risk species than anglers of other races. This finding is encouraging given that minorities are disproportionately affected by contaminants through fish consumption [

12,

26,

27]. The survey results also indicated areas where educational efforts may be improved; for example, all outreach methods were reported as highly effective in the 2013 survey, but were less helpful in 2015. Specifically, the educational pamphlet influenced anglers at the highest rate initially, but significantly decreased in influence by 2015. Furthermore, fewer anglers in 2015 read the signs, and we suspect they may have become part of the “background” of the landscape. This may indicate some level of saturation of knowledge following initial efforts, which corresponds to a drop in new interest in subsequent years. Overall, these trends demonstrate that outreach efforts need to vary over time to reach a broad audience and be maximally effective.

In terms of angler behavior, fish species of greater concern were still some of the most consumed in the later year of the surveys. Overall, this may indicate relative willingness to adjust behaviors with respect to specific species, particularly those like walleye which have deep cultural importance for recreational anglers in this region [

28,

29]. Indeed, walleye and white bass were still the most commonly consumed species among anglers who reported having made changes to the species they consume; however, anglers who were aware of the guidelines or reported making behavioral changes were also willing to supplement their diets with species reported to have lower contaminant levels. This suggests that fish species which are not specifically sought after (due to local importance or lower abundance) may provide greater opportunity for angler behavior change. For example, anglers may be unwilling to remove walleye from their diet, but might consume yellow perch instead of catfish. Species like catfish, which have relatively high contaminant loads but are not favorites among anglers may, thus, provide the greatest opportunity for overall improvement in consumption trends, as resistance to decreasing consumption of those species will be lower.

Race and education were both correlated with overall consumption guideline awareness and the implementation of behavioral change. This may indicate some cultural implications in the perception of messages [

18]. In some cases, despite being aware of guideline suggestions, anglers were not amenable to the overall message, potentially indicating a mistrust of the information [

30]. The suggestions provided may confront generational or cultural tradition, which can make receipt of the information difficult and can hinder implementation of behavioral suggestions [

31]. Incorporation of outreach methods which address familial and cultural concerns over the guideline suggestions need to be considered in designing outreach efforts in this and other systems. Importantly, anglers did report relaying consumption guidelines to friends and family members. Encouraging dissemination of information to friends and family may be a way of improving overall awareness as it allows information to flow through inherently trustworthy sources. However, this method appears to produce more limited results, or else requires more time to become effective given the low number of individuals who had some knowledge of issues with contaminants, but were unaware of the consumption advisory itself. Further utilizing relationships with stakeholder groups in the area could improve translation of research to active anglers, as well as provide educational campaigns with appropriate techniques to effectively engage the public [

32].

In this study, several techniques were assessed for their value in informing local anglers. Signs were posted, River Walkers were hired to engage anglers, and pamphlets were provided with information on consumption guidelines. The assessment using surveys allowed direct feedback on guideline efforts from the target population. Of the outreach efforts utilized, the highest percentage of anglers reported that the signs were most helpful in the later survey year. This suggests that location-specific visual aids which anglers can engage within their own time are important in reaching anglers, and that efforts including such resources may be more effective [

33]. However, the percentage of anglers who found each method to be helpful changed between years which may indicate anglers are not always amenable to the guideline message, or perhaps a decline in the number of anglers who were amenable to the message were encountered due to survey efforts that took place later in the fishing season. Over the course of this study, we identified an increase in the proportion of female anglers, as well as a decrease in the mean age of the angler population. This is consistent with general trends observed in angling communities [

34] and will be important in the design of future advisories, particularly as women of child-bearing age are increasingly engaging in sport fishing, especially in the Great Lakes [

35]. As seen in this study, outreach methods are not equally effective, and better understanding the changing demographics of the audience will aid in designing more effective educational programs.

Importantly, this study surveyed the same geographic population of anglers (though individuals varied) over multiple years to assess changes in behavior associated with educational outreach efforts. Although consumption studies are relatively common, and those which survey anglers produce similar data (e.g., Reference [

36]), few occur over multiple years to assess longer-term changes and retention of guideline information within a population [

37]. This type of repeated sampling is necessary to ensure ongoing impact of consumption guidelines, particularly as information is updated and the angler demographics change. In the case of the Detroit River, consumption guidelines are updated annually; thus, it is imperative that anglers are made aware of recommendations on a continual basis.

This study adopted a unique approach to evaluating the progress of fish consumption guidelines awareness. The face-to-face interaction with individuals who were actively fishing ensured that the target group was reached [

38]. This strategy differs from a majority of previous efforts which relied on phone surveys [

10,

39], online questionnaires, or face-to-face surveys occurring in general public areas not specific to fishing activities [

40]. Furthermore, the anglers who participated in the surveys occupied demographic groups (low income and education, racial minorities) traditionally missed in these types of studies despite being at high risk. This unique design is particularly important for areas with high rates of poverty, such as Detroit, where literacy and access to communication services may be low. Furthermore, this study focused on a specific body of water rather than obtaining data on a larger, regional scale (e.g., Reference [

39]). Data collected from surveys at a regional scale may be difficult to extrapolate to local water bodies and fishing activities (e.g., Reference [

10]). Providing consumption materials and conducting surveys in person at locations where anglers are most likely to be affected by contamination ensures that those individuals who are most likely to be impacted are receiving the information, in addition to providing the greatest possible accuracy in measuring the impact of consumption guideline efforts. This practice also allows for the ability to regularly adapt education and outreach strategies based on feedback directly provided by anglers.