1. Introduction

The financial crisis was triggered on 15 September 2008, when Lehman Brothers bankruptcy led to millions of lost jobs, the doubling of the unemployment rate, the collapse of stock indices, and millions of people out of mortgaged homes. The dramatic effects of the crisis, the diminishing of non-renewable resources, the climate change, and the increasingly pessimistic forecasts of the future of life on planet Earth are the main reasons that support the growing trend of the need to change the business model of the current millennium. Contemporary society implies the need to evaluate companies’ successful business activities not only in terms of immediate economic outcomes, but also from the perspective of current and future social and environmental performance. The sustainable and responsible business model requires companies to make public a lot of non-financial information to test their social responsibility code on environmental protection, care for employees, and the local community through sustainable conservation, biodiversity conservation, promoting cleaner technologies, fair trade, and access to fair employment.

The present study aims to achieve, at Romania’s level, a broad analysis of the performance of the implementation of the EU Directive 34/2013 [

1] (subsequently amended by EU Directive 95/2014 [

2]), which obliges public-interest enterprises with over 500 employees to disclose non-financial information and information on diversity and sustainability. In Romanian legislation, public interest is extended from quoted companies to both state-owned entities and large companies operating as captive employers in areas with high unemployment and, implicitly, with an impact on major social cases in case of layoffs or bankruptcy.

Social responsibility is an actual form of cooperation between governments, businesses, and civil society. Promoting social objectives to defend public interest has implications in economic, political, and social terms, based on the combination of economic elements with moral ones, and pragmatic approaches in close connection with ethical and integrity [

3] (pp. 1091–1106).

In the literature, there are studies dedicated to the social impact assessment revealed by the auditors’ reports evaluated by the auditors [

4] (pp. 1091–1106) or mandatory for certain categories of entities [

5] (pp. 117–131). The effects of quality, environmental, or integrated certifications on listed companies were also analyzed [

6] (pp. 166–180) as well as the role of quality and excellence management with a determinant role in increasing non-financial performance [

7] (pp. 5–7).

This paper is a comprehensive and edifying study based on the exhaustive analysis of the 680-person population responding to the researched field, with about 25% of the number of employees being found within entities with a strong social impact, economically accounting for over 49% of Romania’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Through the results of our research, we bring important clarifications on:

Transposing the above-mentioned European directives into Romanian legislation;

Determining the degree of compliance of Romanian legislation and entities with the requirements and spirit of these directives;

Identifying factors that potentiate or diminish compliance.

The results of our research contribute to the clarification of the mechanisms for coordination, harmonization, and supervision of the implementation of the directives, the organizational framework, and the institutional support granted to the entities involved in the reporting process.

We also appreciate that the results of our research bring a real and important contribution to the improvement of the regulatory framework that requires the target entities to allow free access to the non-financial information for those interested. The mere reporting of this information to the territorial units of the financial administrations, to which the general public does not really have access, does not solve the problem of transparency or accountability, nor does it respond adequately to the spirit of the European directives assimilated recently by the Romanian legislation. The identification of entities with the lowest level of compliance allows the organizational framework to be improved. In addition, it is also very important that the most appropriate means of supporting them can be identified in the implementation of the directives.

From the analysis of the degree of compliance of entities in Romania to their obligation to make non-financial information public through corporate social responsibility (CSR), resulting: (1) Companies supervised by the regulatory and supervisory bodies, respectively by the Bucharest stock exchange (BSE) and by the financial supervision agency (FSA), had a high level of compliance; (2) the entities with the highest level of compliance registered in the entities in which the state is a majority, which have a bureaucratic administrative apparatus but, at the same time, are specialized; (3) the lowest level of compliance has been found in limited liability companies (LLCs), which are also the most dynamic but lack a large administrative apparatus and, in general, are not sufficiently specialized and still lack a culture of business transparency.

It has also been established that the geographical spread of the entities and the number of employees does not have an impact on the level of compliance, while the increase in turnover is a factor that influences it favorably.

We identified the most common published non-financial information that later allowed us to define a sustainable business based on “Customer Health and Safety”, “Resource Efficiency” and “The Role of Intellectual Capital” in environmental protection and biodiversity. At the same time, it was confirmed that the main concerns of “Certification and Authorization” and “Respecting their laws and spirit” are important prerequisites for harnessing the opportunities induced by CSR requirements in business. On the one hand, based on the results analyzed, it was established that “Elaboration of Codes of Ethics and Conduct” and “Defining Procedures to Prevent Conflicts of Interests and Incompatibilities” are the factors with the greatest impact on business integrity and ethics, while: “The open nature of the associations—free competition” is a factor that has the least impact.

The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 1 is dedicated to the review of literature in the field, while the methodology is presented in

Section 2. The main research results are presented in

Section 3, and the last section,

Section 4, is dedicated to the conclusions, implications, and final comments of work.

2. Literature Review

Population and pollution growth, resource mitigation, and climate change are generating new challenges and opportunities for the major players of the global economy and are necessitating the debate and the search for planetary solutions. The great economic and social interests, outlined globally, explain the sinuous and often incoherent evolution of globally accepted solutions. “The global economy is not on the right track, and business does not do what it should to sustain a sustainable future,” says the over 1000 CEOs in 103 countries and 27 industries that participated in the United Nations (UN) Global Compact—Accenture study [

8].

Among the successful solutions that have become more and more enforced in the collective mentality is the one of non-financial reporting, known as corporate social responsibility—CSR. The first CSR reports were published in the late 1980s by US chemical industry companies to mitigate the effects of pollution-related scandals [

9], and then other major polluters have adopted this tactic, which is a good practice for transparent business activity. From voluntary publication to mandatory publication of CSR reports for certain categories of companies, it was only a matter of time, as in the vast majority of European countries, at the beginning of the new millennium, it became necessary to stipulate requirements in national legislation, more or less drastic, about the necessity and content of these non-financial reports.

Trends in the world, but especially in the European space, have made this issue of transparency of the activities of public interest companies also reaching the European Commission’s working table turn into a process of continuous improvement. Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on the annual accounts, consolidated accounts, and related reports of certain types of undertakings, amending Directive 2006/43/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Council Directives 78/660/EEC and 83/349/EEC [

10], stipulates, in Chapter 5, the minimum requirements for the structure and content of the administrator’s report, which must “give a true and fair view of the development and performance of the business and its position, and a description of the main risks and uncertainties it faces, “making public, alongside key performance indicators, wherever relevant, and non-financial indicators relevant to specific activities, including information on environmental issues and staffing; Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards the submission of non-financial information and information on diversity by certain undertakings and large groups requires certain large entities “to make a non-financial statement containing at least environmental, social and personnel information, respect for human rights, combating corruption and bribery,” rigorously presenting policies, results, and risks related to these aspects; in line with Article 2 of Directive 2014/95/EU to facilitate the publication of non-financial information that is “relevant, useful, consistent and comparable”, the European Commission has reported the non-financial information reporting methodology in the “Guidance on reporting non-financial information” [

11], noting that “this Communication includes non-binding recommendations and does not create new legal obligations”. In our study, whenever we refer to the European Directive, it also covers the Directive 2013/34/EU as well as its amendment made by Directive 2014/95/EU.

In line with European legislation, directives need to be transposed into national regulations. Some specialists [

12] believe that the transposition of the European directive into the Romanian legislation by the Ministry of Finance, without calling for the same mass of the representatives of the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Labor, including those directly concerned, is an important prerequisite for the failure of its implementation. The process of transposing Directive 2013/34/EU into Romanian legislation is also a continuous process of improvement. Thus, order no. 1802/2014 of 29 December 2014 for the approval of the Accounting Regulations on the individual annual financial statements and the consolidated annual financial statements [

13], governs in Chapter 7 the structure and content of the directors’ report, developed and assumed by the board of directors. The report should faithfully present the entity’s activities, its position, and a description of the main risks and uncertainties it faces. If necessary, the analysis may include key financial performance indicators and non-financial indicators relevant to specific activities, including environmental and staffing issues. Order no. 1938/2016 of 17 August 2016 on the amendment and supplementation of accounting regulations [

14], requires, as of the financial year 2017, the directors’ reports for public-interest entities that, at the balance sheet date, have an average number of more than 500 employees, to include a non-financial statement containing at least information on environmental, social, and personnel aspects, respect for human rights, and the fight against corruption and bribery. The order further clarifies the justified omission of information on usable reporting frameworks or the exemption of subsidiaries from complying with these requirements. For our research, it is relevant to note that the non-financial statement or the manager’s report including non-financial information is published in accordance with legal requirements once the balance sheet is available or made available to the public within a reasonable time without exceeding six months from the date of publication of the balance sheet, on the entity’s website. Order no. 3456/2018 of 1 November 2018 on the amendment and completion of accounting regulations [

15] extends from the reporting of the financial year 2019, the reporting entity’s non-financial reporting entity, to all entities that, individually or at consolidated level, have an average of over 500 employed whether they are of public interest or not. Also, the obligation to publish non-financial information also rests with European companies with their headquarters in Romania, so also for the subsidiaries of foreign companies where they have their registered office here. The National Bank of Romania (BNR), the Bucharest stock exchange (BVB), and the financial supervision agency (FSA) contributed equally to the mechanism for improving the legislative framework for transposing the EU directives in our country for their respective fields of competence.

Innovation, together with creativity, are the main engines of sustainable development [

16] (pp. 48–64), along with standardization and management quality. According to the standard ISO 26000/2010 [

17], social responsibility refers to: “The actions of an organization to assume responsibility for the impact of its activities on society and the environment so that these actions: be consistent with the interests of society and sustainable development; to rely on ethical behavior and to comply with applicable laws and intergovernmental instruments; be integrated into the organization’s current activities.”

Recent studies also reveal the decisive role of intellectual capital in achieving a sustainable economy of bio economy and biodiversity in our country [

18] (pp. 667–683) as well as in neighboring countries [

19] (pp. 717–731), [

20] (pp. 732–752). In addition, due to its crucial importance as well as its capacity to expand intelligence, stimulate innovation and implement integrity, intellectual capital represents an essential part of any organizational strategy, especially when bringing into discussion aspects such as: innovation and entrepreneurship, knowledge flows and knowledge management, solid investments in human, structural and relational capital, creativity and technological development for economic growth.

Although our study aims, at this stage, only to present a global picture of the level of compliance of the Romanian companies with the requirements of the directive, the analyses were tightened to highlight the most important results and trends of the main categories of entities in office of:

The number of employees,

The size of the turnover,

Main field of activity,

Form of organization,

Property form,

Additional regulatory, reporting, and supervisory requirements,

The geographical area in which they operate, etc.

Thus, general factors can be highlighted to contribute to increasing compliance by identifying causes that have generated a low level of compliance without determining the intensity with which these factors have contributed to increasing or diminishing compliance. These concerns will underpin our continued studies. Previous studies have highlighted the difficulty and complexity of the process of identifying and measuring the causality of social economic processes: “The endogeneity problem has always been one, if not the only, obstacle to understanding the true relationship between different aspects of empirical corporate finance. Variables are typically endogenous, instruments are scarce, and causality relations are complicated” [

21] (p. 149). In our opinion, quantitative empirical studies based on representative samples of data are needed, which at the same time highlight trends but also show contradictory developments before moving to econometric regression models, precisely to mitigate the risks that lead to “leading to biased and inconsistent parameter estimates” [

21] (p. 150), important aspects highlighted in the above mentioned study, which may affect equally “almost every aspect of empirical corporate finance” [

21] (p. 150).

3. Research Methodology

The research methodology was appropriate for the research objectives and characteristics of the population under analysis. We conducted a predominantly descriptive research through a detailed study of the collection, analysis, and interpretation of identified editorial data.

The objective of the research is to evaluate the performance of the implementation of the 2013/34/EU Directive in Romania in its first year of application by making extensive, comprehensive, and current analyses and projections of entities required to publish non-financial information in 2018 for the year that ended on the 31 December 2017; determining the level of national, regional, sectorial, legal compliance; analysis of the completeness of the published non-financial information; identifying the main contributing causes or, on the contrary, those that have made compliance difficult.

To carry out the research [

22] (Chelcea, 2001), the target group was identified and analyzed. Entities required by the European directive to publish non-financial information in 2018 are those of public interest with an average number of employees over 500 in 2017. As there is no official list published with these entities, our starting point was the complete list of the 680 entities identified and published by the CSR report [

23]. The analysis was carried out by investigating both the entire population of the target entities by capitalizing on the information published at the address mentioned above, as well as by expanding studies based on a representative sample of 246 entities selected from the target group.

The population of the analyzed entities, i.e., 680 public-interest companies with more than 500 employees, is a critical mass of social responsibility subject to analysis by social impact; they represent employers for 978,867 employees, almost 25% of employees, but also economically, they have a turnover exceeding ROL 376.524 billion, i.e., over 49% of the GDP of the country in 2015. In terms of ownership, 73.68% have domestic or foreign capital and only 23.32% have majority state capital. Also, 41 of them, i.e., 6%, are listed on the Bucharest stock exchange (BVB). From an organizational point of view, 55.15% are limited liability companies (LLCs), 39.12% are joint-stock companies, 2.35% are autonomous companies (RAs), and 3.38% represent other organizational forms (national companies, research institutes, limited partnerships, public institutions, etc.).

As the survey objectives include the identification of the favorable or inhibitory factors of compliance, the positive, and negative aspects of the compliance process, the sample was not projected in the proportional version, which involves the inclusion in the sample of the proportions of the typologies in the reference population, but the variant optimized layout survey, which reduced the share of homogeneous layers (e.g., the share of LLCs) in the sample and increased the share of heterogeneous layers (e.g., compensated for the layer of state companies or autonomous companies). This method of sample construction provides better quality information and a higher degree of knowledge of the investigated realities.

In the absence of a publicly accessible database, the source for the data on the publication of non-financial information or the administrator’s reports are represented by the websites of the companies in the sample or by the websites of regulatory or supervisory bodies: The BSE website, FSA site, financial investment firm websites, etc. The authors performed cross-checks to ensure the accuracy of the data.

4. Research Results

In order to achieve the research objective, the level of compliance was determined globally, structurally, and territorially. Also, compliance with the content of non-financial reports and corporate social responsibility reports was assessed against the minimum requirements of the directive. The main results and developments were synthesized and presented.

4.1. Measuring Compliance Globally

For determining the degree of compliance at global level, at the sample level, we determined the number of entities that published the administrators’ report or the non-financial statement on their own sites; entities that are exempted under Romanian regulations; and entities that have transmitted or have been published by the supervisory bodies or financial investment bodies. The results obtained, presented in

Table 1, reflect:

Level of compliance at the sample level of the number of entities that published the administrators’ report or the non-financial statement on their own sites. Of the total of 246 entities, only 77 published this information representing 31.31%. This indicator reflects the degree of transparency of corporate social responsibility reports because the purpose and spirit of these reports is to be disclosed voluntarily or compulsorily to the public;

Globally compliant compliance with exempted entities from publication. According to the Romanian regulations transposing the European directive, in 2017, companies’ affiliates are not obliged to publish non-financial information. From the 77 entities analyzed in the sample and added to the 35 previously identified entities, 112 entities have complied, representing 45.53%;

Compliance generally at an expanded global level and with entities for which supervisory, investment, or control coordination bodies have provided information about them. Of the 112 previously identified entities, there are also added: 3 entities identified in the communiqué published by the BSE, 15 of which appear in the materials of the investment bodies, and 24 are published through the materials of the control and coordination bodies of the municipalities and towns, with a total of 62 from 154 representing 60% overall broad conformance degree.

We are convinced that the compliance level is greater than 62.60% in accordance with legal requirements. We must take into account the wide range of Romanian regulations that permitted, for 2017, either the disclosure of non-financial reports to the public or their publication in administrators’ reports with the annual balance sheet based on electronic signature, according to the submission procedures of the annual or half-yearly financial statements to the territorial units of MFP. But as this information is not available to the general public, we believe that these do not meet the spirit of the European directive or its purpose.

4.2. Measuring Degree of Compliance at Structural and Territorial Level

The analysis of the 154 entities underlying the determination of the broad general compliance degree was also achieved at the regional, organizational, and owner-by-business level, by number of employees and turnover. The results obtained are shown in

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 and

Figure 1.

Although some specialty studies require great caution in using one size in empirical analyses “results based on a single size measure should be interpreted with caution” [

24] (p. 3), however, do not exclude the possibility that “researchers can use some alternative size proxies” [

24] (p. 4) whenever “the main measures are not available or are irrelevant” [

24] (p. 26). The aforementioned study also points out that “the choice of size measures needs both theoretical and empirical justification” [

24]. At the present stage of our research, when we have only the primary outcomes of the first year of application of the directive, we want to highlight, on the basis of quantitative analyses, as many trends evaluated from as many perspectives as possible for the empirical justifications needed to substantiate our future studies.

4.2.1. Distribution of the Sample of the Broadly Expanded Compliance Level to the Development Regions

As presented in

Table 2, it is found that the number of entities in the sample is balanced on the development regions, with the exception of Bucharest-Ilfov where the concentration is more pronounced.

The value distribution of the regional compliance indicator is shown in

Figure 1.

It is noted that the level of conformance by development regions has a relatively homogeneous distribution, with a relatively high level in the area of Moldova and the existence of contradictory values, the highest and lowest level in Transylvania, in areas very close to the point geographically as well as business mentality.

In conclusion, the degree of compliance is not influenced by the development region in which the entities have their registered office.

4.2.2. Distribution of the Sample of the Broadly Expanded Level of Compliance to Legal Forms of Organization

From the information in

Table 3, where other organizational forms include a collective company; a research institute, a public institution, and two limited partnerships, it is found that the level of the compliance indicator by legal forms of organization is much lower in the limited liability companies, but instead reaches the maximum value for the autonomous companies whose activity is rigorously regulated and controlled.

4.2.3. Distribution of the Sample of the Broadly Expanded Level of Compliance to Capital Ownership Forms

As presented in

Table 4, it is noted that for entities with a majority ownership of the state, the level of compliance indicator is maximum, while entities with domestic capital have the lowest level of compliance.

4.2.4. Sample Distribution of Broadly Broad Compliance Level According to the Nature of the Activity

As presented in

Table 5, it is found that: The value of the compliance indicator for protection and guarding activities is the lowest. These entities do not have a sophisticated organizational structure, but fulfill the criterion of the number of employees, and the character of public interest was induced solely by the nature of the property. Town halls of localities, i.e., the state, have created their own local protection entities.

Gambling and betting activities also have a low level of compliance, and in our opinion, public interest in these entities is not justified.

The compliance level of only 60% for other industrial activities with environmental impact (cutting and planning of wood, metallurgy, extraction, furniture manufacturing, cement manufacturing, tobacco products, etc.) is considered to be alarming.

4.2.5. Sample Distribution of the Broadly Broad Compliance Level by the Average Number of Employees

Thus, as presented in

Table 6, it is noted that the value of the compliance indicator is not influenced by the average number of employees.

4.2.6. Distribution of Broadly Expanded Broad-Sample Compliance Sample by Turnover

Thus, as presented in

Table 7, it is found that the value of the compliance indicator generally increases with the increase in business figures. There is a certain contradictory development in the ranges from 50 to 100 million lei and from 100 to 500 million lei, requiring additional investigations.

4.3. Measuring the Compliance of the Content Of Non-Financial Reports and Corporate Social Responsibility Reports, According to the Minimum Requirements of the Directive

From the analysis of the non-financial information reporting methodology presented in the guidance on reporting non-financial information in the Commission Communication, the above-described document, we identified the main minimum requirements considered good practices in the field. We will further analyze whether this minimum information was included in the public disclosure reports of Romanian entities and with what frequency they appeared.

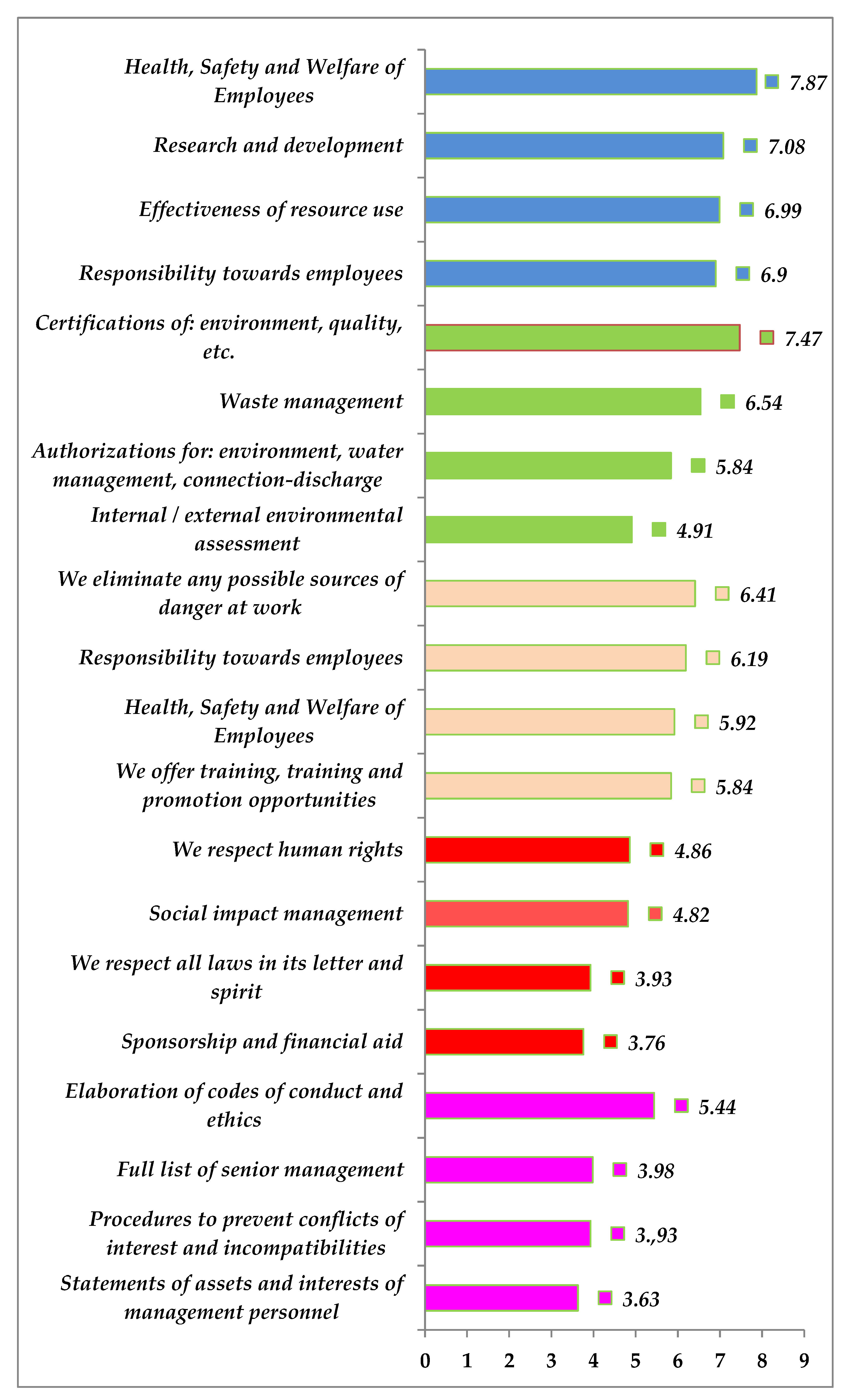

The results of our survey are summarized in

Table 8, which presents the frequency and intensity of the content of this information, and

Figure 2 shows the impact of the most important four disclosures for each criterion.

The diversity of the areas of activity of the entities under consideration justifies the diversity of issues considered relevant to reflect the economic, environmental, and social and integrity impact—presented in the non-financial reports. Also, the importance, intensity, and attribution to the published information is equally heterogeneous. To diminish the diversity effect, we used only three steps for intensity 1 (small), 2 (medium), and 3 (large).

From the analysis of the obtained results, we can summarize the following: The content of the non-financial reports disclosed to the public by the 77 entities analyzed complies 100% with the requirements of the directive and the best practice guide; the frequency of disclosure of certain categories of information or activities is dependent on the specific nature of the activity carried out; the most common information and activities with the greatest impact are shown in

Figure 2.

The results of other studies that we have already done are confirmed by the results of our survey [

25] (pp. 936–938), [

26] (pp. 228–246): Customer health and safety is also a priority for the entities being analyzed; emphasizes the essential role of development research in the sustainable economy, and the importance of intellectual capital.

The frequency with which certifications and authorizations appear in the analyzed non-financial reports reveals that they play an important role in the concerns of stakeholders in capitalizing on the opportunities created by the new, cleaner, safer, and more responsible economy [

27] (pp. 10–27), [

28] (pp. 41–60).

Elimination of possible sources of danger at the workplace and responsibility for the health, safety, and welfare of employees and ensuring training and promotion opportunities confirms, once again, the importance given to human capital and the decisive role of intellectual capital.

Respect for human rights and respect for law in its letter and spirit are further evidence of compliance with the requirements and spirit of the directive.

Ethics and integrity by developing codes of ethics and conduct and defining procedures to prevent conflicts of interest and incompatibilities are the foundation for an ethical and sustainable business promoted by Romanian firms as well.

5. Conclusions and Discussions

The research made it possible to determine the overall transparency indicator based on a very high data sample. Compliance at an expanded overall global level, calculated on the basis of information disclosed to the public directly or through regulatory or supervisory bodies or 62.60% parent companies, is considered to be a good enough result, given the precarious level of training of this event from the point of view of the authorities. The fact that the lowest level of compliance, in the spirit of the directive, to disclose the non-financial information directly to the public of only 41.84% by LLCs, reveals that this new requirement was not sufficiently well publicized and, in addition, the widespread of the Romanian regulations to publish this information in the administrator’s report, directly to the territorial units of the MFP, allowed them to comply in accordance with the Romanian legal requirements, and not with the spirit of the European directive.

As a result of the analysis, the quality of the content of the CSR reports is 100% consistent with the requirements and spirit of the directive. This result provides a high level of confidence in the Romanian business environment and is an additional argument that the premises of a sustainable development of our economy are created. It is also an additional confirmation in support of the growth achieved by the Romanian economy over the past few years, well above the European average.

This is the most comprehensive study on the compliance of entities with the disclosure of non-financial information, based on data on, in particular, the situation of entities that, in 2017, have complied and published the corporate social responsibility reports (CSR). The paper provides essential elements necessary for the knowledge and capitalization of the research results in order to improve the compliance process at both the quantitative and qualitative level in order to accelerate the exceeding of the identified limits. Wide transparency and compliance indicators have been defined and calculated. The main factors influencing the increase in compliance have been identified; some gaps in national transposition legislation have been identified that have diverted its spirit of making certain risks known to the general public and elements of major social or environmental impact known to the general public.

The current research reveals an overview of the compliance of firms with the requirements of the directive and the quality of compliance. Subsequent analysis will identify much more nuanced factors that have favored or disadvantaged compliance. Also, through sectorial analysis, the hierarchy of information, disclosure, economic, environmental, and social or integrity importance could be more hierarchical. The results of the study can be a starting point for either deepening research or identifying the root causes of the main deficiencies found and finding the most appropriate solutions to increase compliance and increasing social responsibility in building a sustainable economy.

Obviously, at this stage, the results of our research have some limitations justified by our concerns that have not focused on the calculation of the intensity of the factors favoring or inhibiting role in influencing the level of compliance or on the theoretical substantiation of causal models that could predict the most likely time-to-time developments in compliance for those categories of disclosure entities and non-financial information. However, by the nuanced analysis of the quantitative results on a sample representative of the analyzed domain, our study decisively contributes to the empirical substantiation of subsequent decisions for expanding and capitalizing on research.