The Sustainability of an Urban Ritual in the Collective Memory: Bergama Kermesi

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Theoretical Background

2. Methodology

3. The Invention of Tradition: Bergama Kermesi

“Gentlemen, the place we are standing upon now is an exceptional corner of our country as it contains unique antiquities. However, it is lost in the dark aisles of the history by being unknown, unseen and unheard. This should come to an end. This place should advertise itself locally and globally. The local people of this exceptional town should be given an opportunity to introduce themselves with a fair and festival…”[30] (p. 9); (Atatürk, 1934)

3.1. Civic Publicness: 1937–1951

3.1.1. Organization

3.1.2. Activities and Spaces

3.1.3. Time

3.2. On the Way to a Civil Society: 1951–1961

3.2.1. Organization

3.2.2. Activities and Spaces

3.3. The International Recognition of the Festival: 1961–1980

3.3.1. Organization

3.3.2. Activities and Spaces

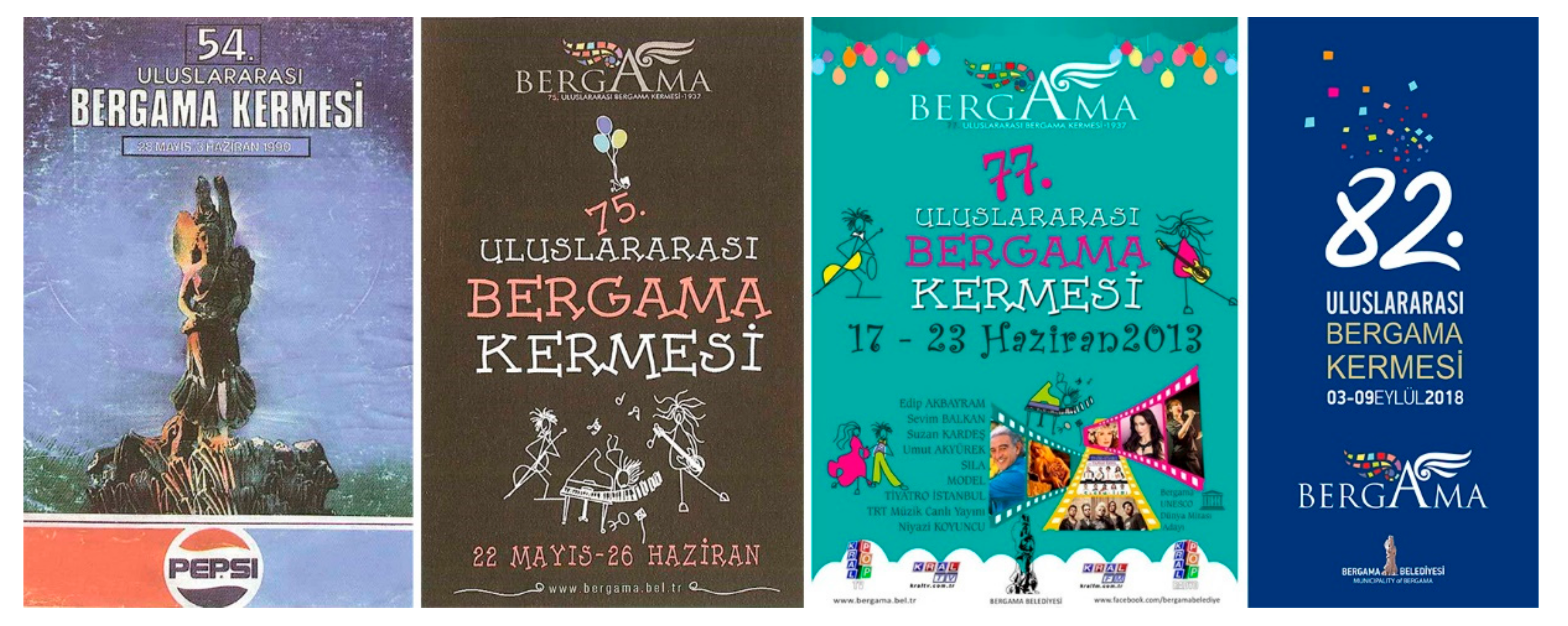

3.4. Civilian Publicness: 1980–Present

3.4.1. Organization

3.4.2. Activities and Spaces

4. Evaluation and Conclusions

4.1. Repetition and Sustainability

4.2. Unity and Plurality

4.3. Publicness and Collectivity

5. Notes

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Event Studies: Theory, Research and Policy for Planned Events; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 113-889-915-1. [Google Scholar]

- Falassi, A. Festival: Definition and Morphology. In Time out of Time: Essays out of the Festival; Falassi, A., Ed.; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1987; pp. 1–10. ISBN 082-630-932-1. [Google Scholar]

- Janiskee, B. South Carolina’s Harvest Festivals: Rural Delights for Day Tripping Urbanites. J. Cult. Geogr. 1980, 1, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. Festivalisation of Urban Spaces Factors, Processes and Effects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-31995-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, A. The Revival of Cultural Celebrations in Regional Sweden. Aspects of Tradition and Transition. Sociol. Rural 1999, 39, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Fontana Press: London, UK, 1993; ISBN 978-000-686-260-4. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.R. Cultural festivals and regional identities in South Korea. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2004, 22, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrett, R. Making sense of how festivals demonstrate a community’s sense of place. Event Manag. 2003, 8, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tao, W. The Revival and Restructuring of a Traditional Folk Festival: Cultural Landscape and Memory in Guangzhou, South China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-022-611-594-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lavenne, F.-X.L.; Renard, V.; Tollet, F. Fiction, between Inner Life and Collective Memory: A Methodological Reflection. New Arcadia Rev. 2005, 3, 1–12. Available online: https://docgo.net/viewdoc.html?utm_source=fiction-between-inner-life-and-collective-memory (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Assmann, J. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-051-199-630-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H. Divali festival in Mauritius. In Rituals and Traditional Events in the Modern World; Laing, J., Frost, W., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 39–50. ISBN 978-041-570-736-7. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, P. How Society Remember; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; ISBN 9780511628061. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawn, E. Introduction: Inventing Tradition. In The Invention of Tradition; Hobsbawn, E., Ranger, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-052-143-773-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawn, E. Mass-Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870–1914. In The Invention of Tradition; Hobsbawn, E., Ranger, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983; pp. 263–307. ISBN 978-052-143-773-3. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, H. Transference of Traditions’ in Tourism: Local Identities as Images Reflected in Infinity Mirrors. Asian J. Tour. Res. 2017, 2, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankova, M.; Vassenska, I. Raising cultural awareness of local traditions through festival tourism. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2015, 11, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Crespi-Vallbona, M.; Richards, G. The Meaning of Cultural Festivals. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2007, 13, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Yeoh, B.S.A. The Construction of National Identity through the Production of Ritual and Spectacle: An Analysis of National Day Parades in Singapore. Political Geogr. 1997, 16, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, F. Celebrating the prophet: Religious nationalism and the politics of Milad-un-Nabi festivals in India. Nations Natl. 2014, 20, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regt, S.; Lippe, T. Does Participation in National Commemorations Increase National Attachment? A Study of Dutch Liberation Festivals. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 2017, 17, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repšienė, R.; Žukauskienė, O. The Song Celebration as Power of Cultural Memory and a Mission of Modernity. J. Res. Cent. Latv. Acad. Cult. 2016, 9, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tekeli, İ. Modernizm, Modernite ve Türkiye’nin Kent Planlama Tarihi; Tarih Vakfı Yurt Publishing: İstanbul, Turkey, 2009; ISBN 978-975-333-234-7. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, J.D. Ethnography; Oxford University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2000; ISBN 0-335-20268-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gillham, B. Case Study Research Methods; Continuum: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-8264-4796. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, S.; Torrance, H. Case Study. In Research Methods in the Social Sciences; Somekh, B., Lewin, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2005; pp. 33–40. ISBN 0-7619-4401-X. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.; Somekh, B. Onservation. In Research Methods in the Social Sciences; Somekh, B., Lewin, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2005; pp. 138–145. ISBN 0-7619-4401-X. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, J.U. Documentary Research Method: New Dimensions. Indus J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2010, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Eriş, E. Kermeslerle Bergama’nın Yakın Tarihi; Bergama Municipality Publishing: İzmir, Turkey, 2011; ISBN 978-605-621-523-0. [Google Scholar]

- Erkmen, A. Osmanlı Türkiyesi ile Cumhuriyet Türkiye’sinin Anı(t)ları: Timsal ve Temsil Üzerine Notlar. In Cumhuriyet’in Mekanları Zamanları İnsanları; Ergut, E.A., İmamoğlu, B., Eds.; Dipnot Yayınları: Ankara, Turkey, 2010; pp. 31–51. ISBN 978-975-905-188-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tanyeli, U. Mekanlar Projeler Anlamları. In Üç Kuşak Cumhuriyet; Tanyeli, U., Ed.; Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı Publishing: İstanbul, Turkey, 1998; pp. 10–107. ISBN 978-975-730-637-5. [Google Scholar]

- BERKSAV (Bergama Foundation of Culture and Art) Home Page. Available online: http://www.berksav.org/2017/kermes.asp (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Bergama’yı Sevenler Cemiyeti. Bergama Kermesi 1937–1946; Dost Publishing: İzmir, Turkey, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Bergama Halk Evleri. Bergama Kermesi 1937; Nefaset Press: İzmir, Turkey, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Gurallar, N. Halkevleri: İdeoloji ve Mimarlık; İletişim Publishing: İstanbul, Turkey, 1999; ISBN 978-975-470-722-9. [Google Scholar]

- Çeçen, A. Halkevleri; Gündoğan Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 1990; ISBN 975-520-022-3. [Google Scholar]

- Katoğlu, M. Cumhuriyetin İlk Yıllarında Sanat ve Kültür Hayatının Oluşumunda Kamu Yönetiminin Yeri. Sanat Dünyamız 2003, 89, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ökeren, H. Bergama Halkevi Yayınlarından 3. (unknown date).

- Elmacı, M.E.; Tınal, M. Bergama Halkevi and Activities in Modernization Process. In Proceedings of the International Bergama Syposium, Bergama, Turkey, 7–9 April 2011; pp. 771–788. [Google Scholar]

- Karadağ, N. Halkevleri Tiyatro Çalışmaları (1932–1951); Ministry of Culture Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 1988; ISBN 978-975-171-928-7.

- Öndin, N. Cumhuriyet’in Kültür Politikası ve Sanat. Sanat Dünyamız 2003, 89, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bakanlıklararası Turizm Komisyonu Raporu (Inter-Ministerial Tourism Commission Report)-BTKR. Bergama Temsilleri ve Turizm İşleri; Başbakanlık Basın ve Yayın Umum Müdürlüğü Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Mardin, Ş. Türk Modernleşmesi; İletişim Publishing: İstanbul, Turkey, 2015; ISBN 978-975-470-144-9. [Google Scholar]

- Uyar, H. Demokrat Parti İktidarında CHP 1950–1960; Doğan Kitap Publishing: İstanbul, Turkey, 2017; ISBN 978-605-094-579-9. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

İnceköse, Ü. The Sustainability of an Urban Ritual in the Collective Memory: Bergama Kermesi. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092684

İnceköse Ü. The Sustainability of an Urban Ritual in the Collective Memory: Bergama Kermesi. Sustainability. 2019; 11(9):2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092684

Chicago/Turabian Styleİnceköse, Ülkü. 2019. "The Sustainability of an Urban Ritual in the Collective Memory: Bergama Kermesi" Sustainability 11, no. 9: 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092684

APA Styleİnceköse, Ü. (2019). The Sustainability of an Urban Ritual in the Collective Memory: Bergama Kermesi. Sustainability, 11(9), 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092684