Abstract

The article addresses the problem of selected technical infrastructure elements (e.g., water supply, sewage, gas networks) in municipalities territorially connected with Polish national parks. Therefore, the research refers to the specific areas: both naturally valuable and attractive in terms of tourism. The time range of the research covers the years 2003–2018. The studied networks were characterized based on the statistical analysis using linear ordering methods; synthetic measures of development were applied. It allowed the ranking construction of the examined municipalities in terms of the development level of water supply, sewage, and gas networks. The results show that the period 2003–2018 was characterized by a development of the analyzed networks in the vast majority of municipalities. Thus, the level of anthropopressure caused by the presence of local community and tourists in municipalities showed a decline. It is worth emphasizing that the infrastructure investments are carried out comprehensively. Favoring investments in the development of any of the abovementioned networks was not observed.

1. Introduction

National parks represent a widely recognized spatial forms of nature conservation, which cover valuable natural areas [1]. There are 23 of national parks in Poland and their total area is only 315 thousand ha (1% of the country area). However, the values they offer make them interesting not only for the nature specific reasons but also in terms of the development of economic, local, and regional systems.

The pursuit of preserving natural heritage, combined with the physical functioning of human beings in space—and bearing in mind that protected areas are not the closed ones—requires appropriate technical infrastructure, which also minimizes the effects of anthropopressure in both the protected and the adjacent urbanized areas. It is all the more important that, apart from the local residents, tourists take advantage of the described spaces. Anthropopressure is the environmental effects of using natural resources to meet people’s needs [2] and results from the impact exerted by both the local community and its visitors. It should be emphasized that the function of tourists in individual municipalities territorially connected with national parks has a different intensity [3] and in the case of parks it has to result from the nature conservation function [4]. It is important to keep in mind that the value streams between the protected area and its surroundings are subject to an ongoing exchange process [5], hence the quality of the broadly approached municipal technical infrastructure has a huge impact on national parks. The fact that nature does not respect administrative boundaries is reflected in Polish legislation. In order to improve the conditions for the protection of fauna, national parks are surrounded by buffer zones within which wild game protection zones are created. Although buffer zones are created by way of regulation issued by the minister competent for the environment, the protection of wild game remains within the responsibility of the director of a given national park [4].

Technical infrastructure consists of many elements (see Section 2). Its basic components have direct impact on reducing environmental pressure and ensure the sanitary safety of its users include the water supply and sewage network. The gas network allows apartment heating to be free from pollution, as the effect of solid fuel combustion is supplementary. Therefore, the long-term characteristics of technical infrastructure aimed at environmental protection (e.g., sewage, water supply networks) and gas network were adopted as the research purpose.

The following research hypothesis was adopted: “In the municipalities territorially connected with national parks, the pursuit towards reducing anthropopressure through the development of water supply, sewage, and gas networks is observed”.

The applied statistical methods are described in detail in the methodological notes. It should, however, be noted that the authors decided to apply synthetic development measures (SDMs). These measures allow for the construction of rankings of the analyzed objects (municipalities) and also the performance of subsequent comparative analyzes. The choice of SDMs resulted from a long tradition of their application and high usability level [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

The research was carried out in the period of 2003–2018 and was based on the data provided by Statistics Poland: Local Date Bank (for details, see methodological notes). The research period derives from the statistical data availability.

2. Infrastructure: The Context of Attractive Protected Areas in Terms of Tourism

The concept of technical infrastructure is quite extensive. Traditionally, it covers transport, communication, power engineering, irrigation, drainage, water supply, sewage, telecommunication, and other devices [13,14]. Following the new approach, it also covers the so-called green infrastructure relevant for the adaptation to climate change [15,16]. For the purposes of environment protection, water supply, sewage, and gas networks are still perceived as luxuries in developing countries. Broadly defined technical infrastructure not only provides comfort and safety to people, but it also aims at minimizing anthropopressure, especially in naturally valuable areas, and its design should remain as neutral in terms of the landscape as possible [17,18].

In Polish conditions, infrastructure investments are within the public sector domain; their significant part is implemented directly by the municipalities [19,20]. The majority of Polish national parks are territorially connected with rural municipalities. Hence, it is worth emphasizing that in rural areas the characteristic feature of the discussed investments is the requirement of cooperation involving local authorities and socio-occupational organizations of farmers, individual farmers, advisory services, and local government administration [21].

An important nuance of the research on technical infrastructure is the fact that some national parks and also the municipalities connected with them represent popular tourist destinations, and are thus affected by the phenomenon of mass tourism [22,23,24] and the related problems characteristic for Poland’s most popular places [25]. A growing interest in both education and tourism in national parks has been observed for several years. It is extremely important that in the context of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) reports, it is indicated that there is an ongoing increase in tourism-oriented activity and, thus, tourism has become the foundation of local development [26]. A growing number of people that visit a given space automatically translates into a higher burden on infrastructure and demand for resources. The problem of water supply and sewage network efficiency and the available drinking water resources is of the utmost importance. At this point it is worth highlighting that Poland is a very poor country in terms of water [27,28].

3. Methodological Remarks

The research was initiated with a library query. Due to the fact that the term “technical infrastructure” is complex and covers many elements of the conducted research, it was limited to the selected aspects as the most important for environment protection, i.e., water supply, sewage, and gas networks.

During our research, statistical tools were used that allowed us to obtain results useful for presenting conclusions and recommendations. It was decided to apply analytical methods, including the linear ordering method—i.e, synthetic development measures (SDMs). It was adopted that the analyzed municipalities form one set of 117 objects. SDM was developed in three examined areas: the water supply network (SDMwater), the sewage network (SDMsewage), and the gas network (SDMgas).

It should be emphasized that not all municipalities reported the existence of the analyzed infrastructure elements. The following three municipalities reported no sewage network: Giby, Krasnopol, and Kobylin-Borzymy. As many as 17 municipalities reported no gas network: Sosnowica, Stary Brus, Urszulin, Kamienica, Szczawnica, Zawoja, Lutowiska, Bargłów Kościelny, Lipsk, Grajewo, Radziłów, Jedwabne, Wizna, Giby, Krasnopol, Nowy Dwór, and Szczawnica. To maintain SDM comparability in the abovementioned cases, the data were supplemented with zero values. These municipalities were finally assigned the last, equivalent position.

The identification of municipalities territorially connected with national parks was the first step of the conducted research procedure.

The construction of SDM started with determining variables for all three measures. Next, the variables were unified for the entire period simultaneously, i.e., for the years 2003–2018. Using the standardized sum method, SDM was developed with a weight system (a common development pattern was adopted for the entire analyzed period). It allowed us to determine in each analyzed year the ranking positions of municipalities developed for individual SDMs and to compare the changes in terms of the positions taken by the municipalities in these rankings.

The following indicators were defined for the purposes of determining SDMwater:

- accessibility index of social water supply network (DSwater)

- adjusted accessibility index of social water supply network (SDSwater)

- accessibility index of spatial water supply network (DPwater)

- index of population using water supply network (Lwater)

To determine SDMsewage the following indicators were defined:

- accessibility index of social sewage network (DSsewage)

- adjusted accessibility index of social sewage network (SDSsewage)

- accessibility index of spatial sewage network (DPsewage)

- index of population using sewage network (Lsewage)

It should be clarified that the calculation of the adjusted SDSwater and SDSsewage indexes was intended to capture both water supply and sewage networks’ usage by tourists. The authors are aware of the imperfections inherent in the proposed measures, as they do not cover seasonal fluctuations or hikers (i.e., people not using accommodation) [29], but the availability of statistical data and the simultaneous striving to maintain comparability of the research results for all 117 municipalities did not allow for a different construction. Statistics Poland provides the total number of tourists for the entire year. Dividing this value by 365 days allowed us to obtain the average number of tourists each day of the year. The number of residents, according to the Statistics Poland data, is constant for all days of the year. Therefore, adding these values allows showing the adjusted number of people using the networks under study and, hence, presenting the synthetic measure of social accessibility of the analyzed networks.

To determine SDMgas the following indicators were defined:

- index of population using gas network (Lgas)

- index of population heating the apartment with gas (Ogas)

Due to the fact that Statistics Poland only provides data regarding the length of the functioning gas network for the years 2003–2006, the calculation of analogical indicators, as in the case of the previous two SDMs, was not possible. The data on the population heating their apartments with gas also needed to be supplemented. Statistics Poland presents data only for the period 2005–2018, so the data covering the years 2003–2004 were adopted at the level of the data for 2005.

For all three SDMs, the Statistics Poland [30] data were used to calculate the listed indicators. All of them were considered stimulants without veto threshold, which means that the municipalities that presented high values of the aforementioned indicators were assessed as the units with the highest-ranking positions.

Unitarization procedure was performed after determining indicators for each SDM [31]. The unitarization covering values of the features adopted for the study was carried out according to the following formula:

notes:

- x: feature value

- j: j variable, where j = (1, …, p)

- i: object (municipality), where I = (1,…, N),

- N for each SDM = 117

- T: time (year), where t = (2003, 2004, …, 2018)

Unitarization resulted in obtaining values in the range [0,1]. There was no need to harmonize variables’ character (preference function) as they were all stimulants in each SDM. SDM was calculated using the standardized sum method [32]. The value of SDM for the analyzed municipalities was calculated using Equation (12):

notes:

- SDM: value of the non-model synthetic measure in an object (municipality) and

- p: number of features.

For all four SDMs presented above, the highest value is equivalent to the most favorable situation. In the final phase, ranking positions were assigned to the analyzed municipalities and comparisons were made regarding the position determined by the analyzed SDMs.

It should be emphasized that for the purposes of the presented data readability, the tables present data for the selected years, i.e., 2003 and 2018 (the first and the last year of the study).

4. Level and Transformations of the Selected Technical Infrastructure Elements in the Municipalities Territorially Connected with National Parks

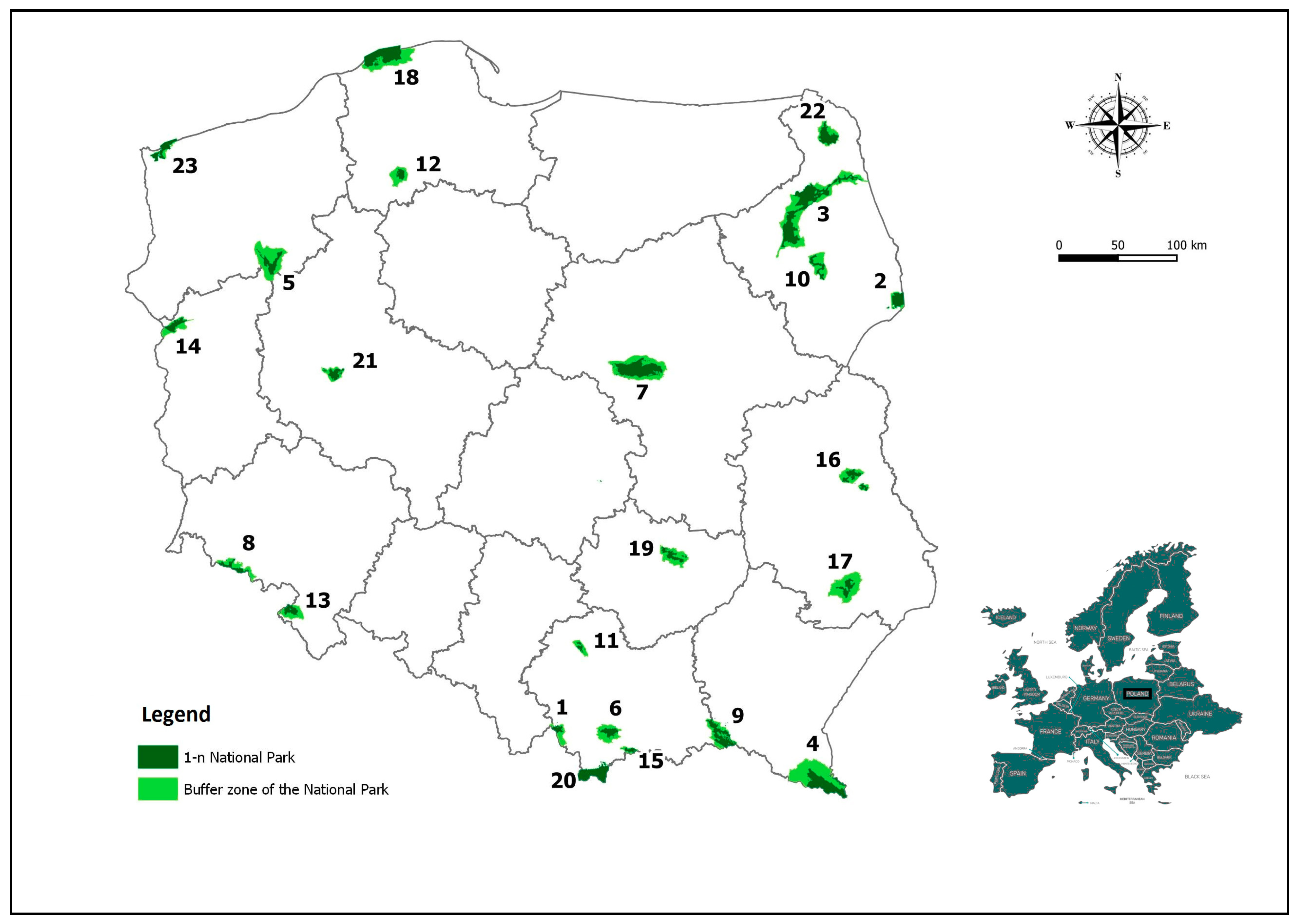

The analysis of the studied areas’ location allows stating that national parks include coastal, lake, lowland, upland, and mountain areas (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The location of Polish national parks and their buffer zones against the background of the administrative division of the country (voivodship level). Legend: Buffer zone: the area in which protection zones for wild game are created. 1. Babia Góra National Park, 2. Białowieża National Park, 3. Biebrza National Park, 4. Bieszczady National Park, 5. Drawno National Park, 6. Gorce National Park, 7. Kampinos National Park, 8. Karkonosze National Park, 9. Magura National Park, 10. Narew National Park, 11. Ojców National Park, 12. Bory Tucholskie National Park, 13. Stolowe Mountains National Park, 14. Warta Mouth National Park, 15. Pieniny National Park, 16. Polesie National Park, 17. Roztocze National Park, 18. Słowiński National Park, 19. Świętokrzyski National Park, 20. Tatra National Park, 21. Wielkopolska National Park, 22. Wigry National Park, and 23. Wolin National Park.

The administrative division in Poland identifies municipalities, districts, and voivodships. Voivodships correspond to the second level of geocoding in the European Union, the so-called Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS). Due to their importance for the correct identification of the detailed location of individual national parks, the boundaries of NUTS 2 are presented in Figure 1.

The identification of municipalities territorially connected with Polish national parks is presented in the table below (Table 1). It should be emphasized that national parks are territorially connected with as many as 117 municipalities (11 of them have the status of an urban municipality, 31 the status of an urban-rural municipality, and 75 the status of a rural municipality).

Table 1.

Municipalities territorially connected with national parks in Poland.

As it has been indicated in methodological notes, SDMs were used to describe the analyzed elements of technical infrastructure. The research results for the first and the last year of the study are presented in the table below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Synthetic development measures (SDMs) of water supply, sewage, and gas network for the municipalities territorially connected with national parks. Data covers the years 2003 and 2018.

The municipalities ranked among the top 10 in the analyzed period, based on the rankings taking into account the values of three SDMs, are presented in the table below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ranking leaders SDMwater SDMsewage and SDMgas in the years 2003–2018.

It is characteristic that some of the municipalities are listed among the leaders of the rankings developed based on various SDMs. This suggests that infrastructural investments are implemented comprehensively. If a municipality has the respective financial resources, it invests simultaneously in the construction of the three analyzed networks. No regularity can be identified regarding the location of the municipalities-leaders. These municipalities are characterized by a different status (urban, rural, and urban-rural) and are connected with different national parks.

The analysis indicates a relative stability of SDMwater leaders. In the entire research period, this group included 17 municipalities. The municipalities connected with Biebrza National Park (NP), i.e., Bargłów Kościelny, and Nowy Dwór, throughout the entire studied period, were ranked as the first and the second, respectively. The comparison of positions at the beginning and at the end of the analyzed period shows that 66 examined municipalities recorded a lower, 46 a higher, and 5 maintained their position. The majority of municipalities showed changes in their ranking position. Only 40% of the municipalities changed their position by a one-digit value. In terms of growth, Leipzig (connected with Biebrza NP) was the dominating one (increased by 80 positions in the ranking), whereas the largest drop (by 58 positions) was recorded by Jabłonka municipality (Babia Góra NP).

The absolute growth in SDMwater value, calculated as the difference in SDMwater value in 2018 (analyzed) and 2003 (baseline), indicates that the measure value dropped only in 12 municipalities: Jabłonka, Nowy Targ, Nowy Żmigród, Piechowice, Lipnica Wielka, Chojnice, Szczytna Lutowiska, Bukowina Tatrzańska, Dopiewo, Mszana Dolna, and Turośń Kościelna. It means that the development of water supply network was recorded in the vast majority (90%) of municipalities, levelling off the increase in the number of users.

Positive changes in the value of SDMwater were primarily the consequence of a longer distribution network; as many as 106 municipalities extended their water supply network. Łomianki municipality was the leader in this respect (the length of the functioning distribution network increased by 144 km). It should be noted, however, that this municipality is territorially connected with Kampinos NP and located near the country capital. Łomianki—in a sense—was affected by the suburbanization phenomenon, resulting from the residential housing pressure of Warsaw community.

The observations during the period 2003–2018 allow stating that the infrastructure that provides access to water is developing in the vast majority of the analyzed municipalities. This phenomenon should definitely be considered a positive one.

This analysis indicates that in the case of SDMsewage the leadership changes were much greater than in relation to SDMwater. In the analyzed period, 27 municipalities were listed among the top ones. In the Ustka municipality, which is connected with Słowiński, NP was the leader and for most part the studied period was ranked first. The second position was undisputedly taken by the Puszczykowo municipality located near Poznań metropolis (Wielkopolska NP).

The comparison of positions occupied at the beginning and at end of the research period shows that 68 analyzed municipalities recorded lower and 48 higher, while one maintained its ranking position. The majority of municipalities were characterized by significant changes in their ranking positions. Only 23% of them changed their position by a one-digit value. In terms of growth, Sułoszowa municipality connected with Ojców NP dominated (increase by 103 places in the ranking) and the largest drop (by 58 places) was noted for Szczytna municipality (Stołowe Mountains National Park).

The absolute growth in SDMsewage value, calculated as the difference in SDMsewage value in 2018 (analyzed) and 2003 (baseline), indicates that the measure value dropped only in three municipalities: Szczytna, Hańsk, and Grajewo. Due to the fact that the sewage network does not exist in all the municipalities of Giby, Krasnopol, and Kobylin-Bokuje, (they occupied ex aequo in the last position in the ranking), it can be stated that in approximately 95% of the analyzed municipalities in the sewage network development leveled off the increase in the number of users.

Positive changes in the value of SDMsewage resulted mostly from the increase in the length of sewage network. As many as 106 municipalities recorded this network extension. The Jabłonka municipality, which is connected with Babia Góra NP, was the leader in this respect (the length of the network increased by 106 km).

The observations made for the period 2003–2018 allow stating that the sewage infrastructure is under development in the vast majority of the analyzed municipalities. This phenomenon should definitely be considered a positive one.

The analysis shows that in the case of SDMgas, the group of leaders included 17 municipalities, which was identical for SDMwater. Keepin in mind that as many as 17 units did not have a gas network during the study period (thus ranked ex aequo at the last position), it can be adopted that the variability in this respect was slightly higher than in the case of SDMwater. The unquestionable ranking leaders were: Łomianki municipality (first or second ranking position throughout the entire analyzed period) and Stare Babice municipality (first or second position, and incidentally, in 2008, fourth in the ranking) connected with Kampinos NP, and located in the vicinity of Warsaw.

The comparison of positions from the beginning and the end of the analyzed period shows that 87 examined municipalities recorded a decrease and 25 an increase, while five maintained their position. In total, 60 municipalities changed their position by two-digit values, which constituted a slight majority. In terms of growth, Dopiewo municipality connected with Wielkopolska NP was the dominating one (increase by 24 ranking positions) and the largest drop (73 places) was recorded by the Krempna municipality (Magura NP).

The absolute growth in SDMgas value, calculated as the difference in SDMgas value in 2018 (analysed) and 2003 (baseline), indicates that the measure value dropped in 15 municipalities: Świnoujście, Lewin Kłodzki, Stare Babice, Kudowa-Zdrój, Jelenia Góra, Kowary, Piechowice, Dębowiec, Radków, Czarna, Dukla, Krempna, Leoncin, and Izabelin oraz Brusy.

Bearing in mind that the gas network is nonexistent in the municipalities of Sosnowica, Stary Brus, Urszulin, Kamienica, Szczawnica, Zawoja, Lutowiska, Bargłów Kościelny, Lipsk, Grajewo, Radziłów, Jedwabne, Wizna, Giby, Krasnopol, Nowy Dwór, and Szczawnica (they occupied ex aequo the last ranking position), it can be stated that the development of a gas network was recorded in almost 73% of the analyzed municipalities, which leveled off the increase in the number of users.

Positive changes in SDMgas value derived mainly from a larger number of populations using gas networks. Due to the absence of data on the length of a functioning network, it can be presumed that not only the number of connections but the length of the network increased. The development of the gas network in the analyzed municipalities should be assessed positively.

5. Discussion

It is difficult to indicate the research comparable to the one presented in the article. The authors are aware of this situation and the reasons for no comparability of the studies on Polish national parks with the national parks in other countries have already been described in detail [3]. Although national parks are known worldwide, this term is associated with different security regimes in various countries, as well as organizational and legal differences resulting from the functioning forms of such parks and also the rights and entitlements of local authorities. These differences often result from just the size of the park. However, the above does not change the fact that Polish national parks represent an important link in the protection of European nature and also an important destination for domestic tourist traffic.

The specificity of protected areas means that from both natural and economic perspectives it is important to properly understand the message presented on the Federation of Nature and National Parks of Europe (EUROPARC Federation) website: “nature knows no boundaries” [33]. Nature protection requirements are not synonymous with the need to eliminate a human being from the protected space. The research results indicate that the function of nature conservation, as well as the economic functions (including tourism), are not mutually exclusive [34]. However, the communities residing in the municipalities territorially connected with national parks, the investors operating within the discussed area and also tourists have to comply with stricter environmental standards.

Users make space evolve, as it changes physically and functionally. This refers to both urban space [35,36], rural areas [37,38], and valuable natural areas the least changed by a man. Therefore, in the context of the presented article, this phenomenon applies to the area of national parks and the areas of municipalities connected with them.

The EUROPARC Federation clearly emphasizes that sustainable tourism is desirable for both parks and people (in the sense of local communities and tourists). At the same time, it should be emphasized that the concept of sustainable tourism is still open and widely discussed. Even though there is a consensus regarding the principle that an ongoing and sustainable development of tourism is such a method for doing business and organizing social life, which ensures both the development and preservation of the environmental values along with improving the quality of people’s lives, there are still many detailed interpretations of the discussed concept [39,40].

Balancing the tourist function not only takes time but it remains a complicated process [33,40]. The significance of the aforementioned issue is also strengthened by the fact that 2017 was announced the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development.

To sum up, it can be stated that technical infrastructure is indispensable not only for the development of economic initiatives (including the who influences the multifunctional and sustainable development of municipalities. It is natural, then, that technical infrastructure has to be supplemented by social infrastructure (these problems—although very interesting—are not the subject matter of this article).

6. Conclusions

The conducted empirical research allowed us to achieve our defined research goals. We were forced to adjust the adopted indicators to the available statistical data. Despite that, we managed to develop measures that allowed for a comprehensive and measurable approach to the analyzed problems.

The collected results allowed us to conclude that, between 2003–2018, the development of the analyzed technical infrastructure elements were recorded in the vast majority of municipalities. Therefore, the level of anthropopressure declined, which was caused by the local community and tourists in municipalities within the most valuable natural areas.

The largest percentage of municipalities that were characterized by an increase in synthetic development measures were referred to sewerage network research. As many as 95% of the analyzed municipalities recorded an increase in the absolute value of SDMsewage in the period 2003–2018. Slightly lower values were true for the water supply network, in the case of which development was observed in 90% of municipalities. The poorest—although not to be considered bad—refer to the gas network. In total, 73% of the studied municipalities recorded development in this area.

In view of the above, the research hypothesis put forward at the beginning of the article should be adopted and it should be recognized that the development of water supply, sewage, and gas networks is observed in the municipalities territorially connected with national parks.

The interpretation of the collected results (SDMwater, SDMsewage, and SDMgas) highlight an important nuance: in the set of 117 units there are both urban municipalities which, in the past, played the role of voivodship capitals (Jelenia Góra), and also rural municipalities inhabited by less than 2000 people (Lewin Kłodzki, Cisna). Hence, the settlement and population system as well as the wealth of local governments in the analyzed municipalities are very different. It is highly positive that despite the abovementioned differences, the municipalities remain connected not only by their tourist attractiveness and unique nature, but also by striving to protect it. Its measurable expression is the identified development of the analyzed technical infrastructure elements, which is highly important in the context of aiming at sustainable tourism development in the naturally valuable areas.

Summing up the presented discussion it should, yet again, be emphasized that the processes occurring in the environment or the exchange of value streams between specific spaces do not respect the administrative boundaries of the protected area. Therefore, the functioning of the analyzed technical infrastructure is extremely important for the nature protection of national parks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.K.-D.; Data curation: A.K.-D. and A.S.; Formal analysis: A.K.-D. and A.S.; Investigation: A.K.-D.; Methodology: A.K.-D.; Resources: A.K.-D.; Supervision: A.K.-D.; Visualization: A.S.; Writing—review & editing: A.K.-D. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Environmental and Life Sciences (no external funding).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNEP-WCMC and IUCN. Protected Planet Report 2016; UNEP-WCMC and IUCN: Cambridge, UK; Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kennish, M.J. Anthropogenic Impacts. In Encyclopedia of Estuaries; Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series; Kennish, M.J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczyk-Dynowska, A.; Bal-Domańska, B. The National Parks in the Context of Tourist Function Development in Territorially Linked Municipalities in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Act of 16 April 2004 on Nature Conservation Journal of Laws of 2004, No. 92, Item 880. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20040920880/U/D20040880Lj.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Koda, E.; Sieczka, A.; Osinski, P. Ammonium concentration and migration in groundwater in the vicinity of waste management site located in the neighborhood of protected areas of Warsaw, Poland. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, Z. Zastosowanie metody taksonomicznej do typologicznego podziału krajów ze względu na poziom ich rozwoju oraz zasoby i strukturę wykwalifikowanych kadr/The application of taxonomic method in the typological division of countries regarding their development level and resources and structure of qualified personnel. Stat. Rev. 1968, 4, 307–327. [Google Scholar]

- Strahl, D. Propozycja konstrukcji miary syntetycznej/The proposal of statistical measure construction. Stat. Rev. 1978, 25, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Walesiak, M. Uogólniona Miara Odległości w Statystycznej Analizie Wielowymiarowej/Generalized Distance Measure in a Statistical Multidimensional Analysis; University of Economics in Wrocław Press: Wrocław, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marti, R.; Reinelt, G. The Linear Ordering Problem, Exact and Heuristic Methods in Combinatorial Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K. Propozycja budowy rankingu obiektów z wykorzystaniem cech ilościowych oraz jakościowych. Metod. Ilościowe w Badaniach Ekonomicznych 2012, 13, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K.; Luty, L. Jeszcze o procedurze wyboru metody porządkowania liniowego. Stat. Rev. 2017, 64, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Manly, B.F.J.; Navarro Alberto, J.A. Multivariate Statistical Methods; CRC Press/Taylor& Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Górz, B.; Kurek, W. Variations in technical infrastructure and private economic activity in the rural areas of Southern Poland. GeoJournal 1998, 46, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.P.; Florida, R. The geographic sources of innovation: Technological infrastructure and product innovation in the United States. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1994, 84, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, J.; Chruściński, J.; Szewrański, S. The Development of a Novel Decision Support System for the Location of Green Infrastructure for Stormwater Management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiełkowska, J.; Tokarczyk-Dorociak, K.; Kazak, J.; Szewrański, S.; Van Hoof, J. Urban Adaptation to Climate Change Plans and Policies–the Conceptual Framework of a Methodological Approach. J. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 19, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, P. Monitoring of Landscape Transformations within Landscape Parks in Poland in the 21st Century. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilig, G.K. Multifunctionality of landscapes and ecosystem services with respect to rural development. In Sustainable Development of Multifunctional Landscapes; Helming, K., Wiggering, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, M. Technical infrastructure investments in municipality—A theoretical outline. Bibl. Reg. 2010, 10, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Furmankiewicz, M.; Macken-Walsh, A.; Stefańska, J. Territorial governance, networks and power: Cross-sectoral partnerships in rural Poland. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2014, 96, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickiewicz, A.; Wawrzyniak, B. The Importance of Technical Infrastructure for the Development of Rural Areas. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2011, 166, 483–493. [Google Scholar]

- Przybyła, K.; Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. Transformations of Tourist Functions in Urban Areas of the Karkonosze Mountains. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2001; Volume 245, p. 072001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walas, B.; Fedyk, W.; Pasierbek, T.; Nemethy, S. Diagnosis of functioning of National Parks in Poland in their socioeconomic environment. Ekonomiczne Problemy Turystyki 2018, 43, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawilińska, B.; Mika, M. National parks and local development in Poland: A municipal perspective. Hum. Geogr. J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.; Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B. The Attitude of Tourist Destination Residents towards the Effects of Overtourism—Kraków Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Annual Report 2017; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018; p. 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioduszewski, W. Czy Polska jest krajem ubogim w wodę? Gospodarka Wodna 2008, 5, 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- Orlińska-Woźniak, P.; Wik, P.; Gębala, J. Water availability in reference to water needs in Poland. Meteorol. Hydrol. Water Manag. Res. Oper. Appl. 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warszyńska, J.; Jackowski, A. Podstawy Geografii Turyzmu/Basics in Tourism Geography; PWN Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland, Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/start (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Kukuła, K. Zero unitarisation method as a tool in ranking research. Econ. Sci. Rural Dev. 2014, 36, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski, G. Metody Porządkowania Liniowego; Dziechciarz, J., Ed.; Ekonometria, Wyd. Akademii Ekonomicznej: Wrocław, Poland, 2002; pp. 287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: www.europarc.org (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. Parki Narodowe a Funkcje Turystyczne i Gospodarcze Gmin Terytorialnie Powiązanych; Wyd. Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Słodczyk, J. Przestrzeń Miasta i Jej Przeobrażenia; Studia i Monografie; Uniwersytet Opolski: Opole, Poland, 2003; Volume 298. [Google Scholar]

- March, L.; Martin, L. (Eds.) Urban Space and Structures; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Woch, F.; Woch, R. Zmiany użytkowania przestrzeni wiejskiej w Polsce. Infrastruktura i Ekologia Terenów Wiejskich 2014, I/1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacherzak, A.; Hełdak, M.; Hajek, L.; Przybyła, K. State Interventionism in Agricultural Land Turnover in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrevska, B.; Terzi’c, A.; Andreeski, C. More or Less Sustainable? Assessment from a Policy Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, P.A. Supporting the principles of sustainable development in tourism and ecotourism: Government’s potential role. Curr. Issues Tour. 2002, 5, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).