Towards a Tourism and Community-Development Framework: An African Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Understanding Key Concepts

2.1. The Community Concept

2.2. The Development Concept

2.3. Community Development

2.4. Poverty in Communities

3. Tourism and Community Development

3.1. Community-Based Tourism

Community-Based Tourism Models

3.2. Pro-Poor Tourism

Due to its ability to increase net benefits for the poor, PPT has the capacity to promote linkages between the tourism industry and the poor [164]. It is different from other types of tourism in that it has poverty as its key focus [164].Tourism interventions that aim to increase the net benefits for the poor from tourism, and ensure that tourism growth contributes to poverty reduction. PPT is not a specific product or sector of tourism, but an approach. PPT strategies aim to unlock opportunities for the poor—whether for economic gain, other livelihood benefits, or participation in decision making.[167]

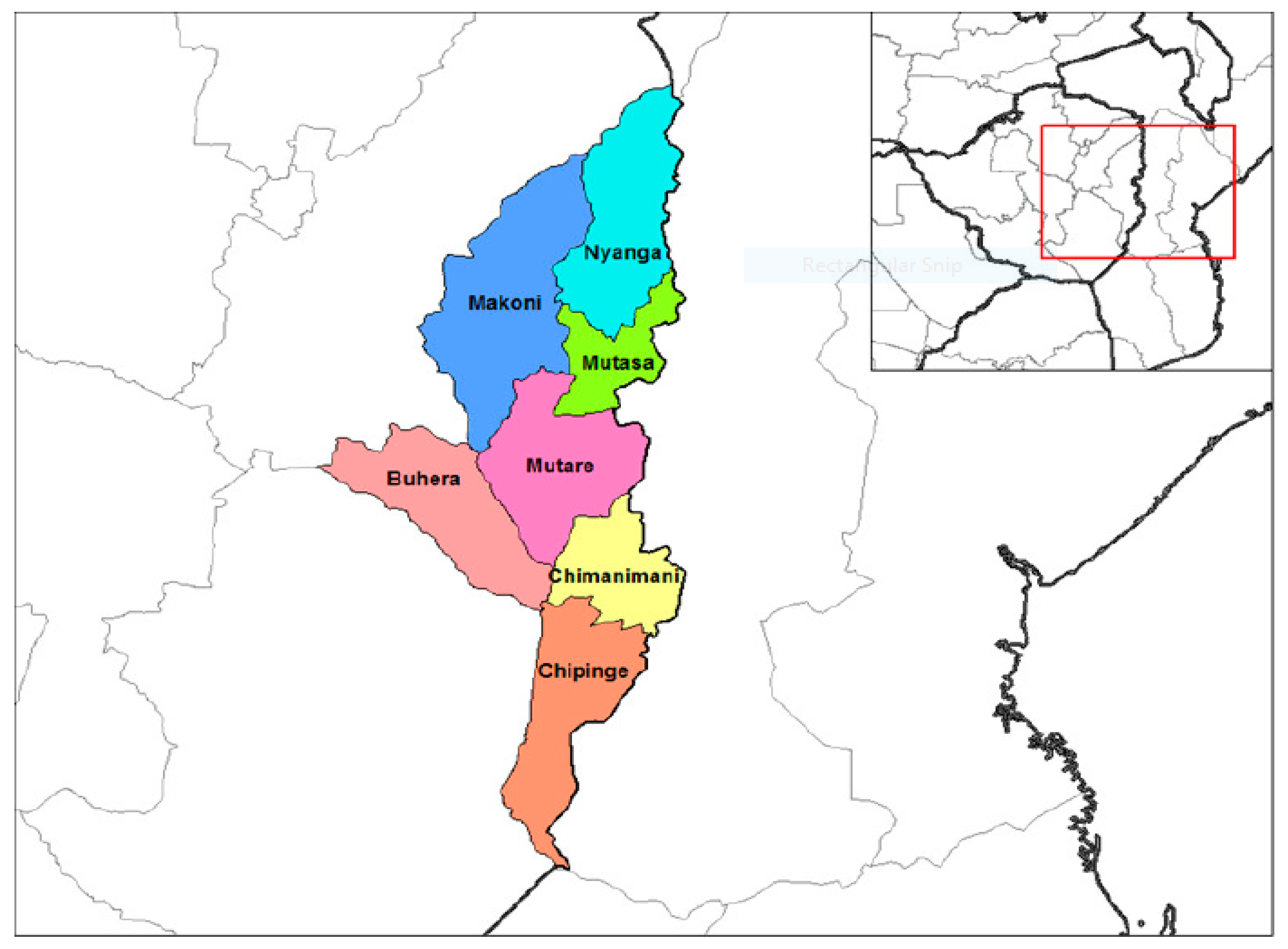

4. Background on Manicaland Province

4.1. Poverty in Manicaland

4.2. Tourism Development in Manicaland

5. Research Methodology

6. Results

6.1. Interviewees’ Profiles

6.2. Local People’s Perceptions of Tourism as a Means of Poverty Alleviation

6.3. Perceptions of Tourism as a Means of Community Development

7. Discussion

7.1. Towards a Tourism and Community-Development Framework

7.2. Macro Environment

7.3. Poor Community Residents

7.4. Tourism Development

7.5. Training Programmes

7.6. Direct and Indirect Tourism Benefits

7.7. Poverty Alleviation

7.8. Community Development

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Przeclawski, K. Deontology of tourism. Prog. Tour. Hosp. Res. 1996, 2, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Annual Report 2016; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, I.; Fernandes, E.; Messerli, H.; Twining-Ward, L. Tourism in Africa: Harnessing Tourism for Growth and Improved Livelihoods; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Tourism Trends and Policies Highlights. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/tour-2016-en.pdf?expires=1594104965&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=36D7F7CE1D595F2DD23EA0ED2F9618C4 (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). Travel & Tourism Economic Impact: World; WTTC: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Tourism Towards 2030/Global Overview; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adeola, O.; Evans, O.; Hinson, R.E. Tourism and economic wellbeing in Africa. MPRA 2018, 93685, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H.; Santilli, R. Community-based tourism: A success. ICRT Occas. Pap. 2009, 11, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Mutana, S. Rural tourism for pro-poor development in Zimbabwean rural communities: Prospects in Binga rural district along Lake Kariba. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R.; Telfer, D. Introduction: Tourism and development: A decade of change. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Sharpley, R., Telfer, D., Eds.; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2014; pp. xi–xxii. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Tourism for Development: Key areas for Action; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Wide for Nature (WWF). Guidelines for Community-Based Ecotourism Development; WWF International: Gland, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism as a community industry—An ecological model of tourism development. Tour. Manag. 1983, 4, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudiwa, M. Global or local commons? Biodiversity, indigenous knowledge and intellectual property rights. In Managing Common Property in An Age of Globalisation: Zimbabwean Experiences; Chikowore, G., Manzungu, E., Mushayavanhu, D., Shoko, D., Eds.; Weaver Press: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2002; pp. 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge, D.; Hales, R. Community case study research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Tourism: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches; Dwyer, L., Gill, A., Seetaram, N., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; pp. 417–437. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.W. Community Development; University College Rhodesia: Salisbury, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Kepe, T. The problem of defining community: Challenges of the land reform programme in rural South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 1999, 16, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devere, H. Peacebuilding within and between communities. In Identity, Culture and the Politics of Community Development; Wilson, S.A., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars: Newcastle, UK, 2015; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, R. Community Economic Development: Key Concepts; Mississippi State University Extension Services: Mississipi, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Okocha, M. Building bridges: Community radio as a tool for national development in Nigeria. In Identity, Culture and the Politics of Community Development; Wilson, S.A., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars: Newcastle, UK, 2015; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, G. Community capacity-building: Something old, something new…? Crit. Soc. Policy 2007, 27, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verity, F. Community Capacity Building—A Review of the Literature; South Australian Department of Health: Adelaide, Australia, 2007.

- Bhattacharyya, J. Solidarity and agency: Rethinking community development. Hum. Organ. 1995, 54, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, R.; Deller, S.; Marcouiller, D. Rethinking community economic development. Econ. Dev. Q. 2006, 20, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.W.; Mair, H.; Reid, D.G. Rural Tourism Development: Localism and Cultural Change; Channel View: Ontario, ON, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Snyman, S.L. The role of tourism employment in poverty reduction and community perceptions of conservation and tourism in southern Africa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeton, S. Community Development through Tourism; Landlinks: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hinch, T.; Butler, R. Introduction: Revisiting common ground. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Telfer , D.J.; Sharpley, R. Tourism and Development in the Developing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.C. The Process of Development of Societies; Sage: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury, D. Introduction. In Key Issues in Development; Kingsbury, D., Remenyi, J., Mckay, J., Hunt, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Croswell, J.M. Basic Human Needs: A Development Planning Approach; Oelgeschlager: Cambridge, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Remenyi, J. What is development? In Key Issues in Development; Kingsbury, D., Remenyi, J., Mckay, J., Hunt, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.; Hughey, K.F.D.; Simmons, D.G. Connecting the sustainable livelihoods approach and tourism: A review of the literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2008, 15, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Tourism for Development: Empowering Communities; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. The concept of development. In Handbook of Development Economics; Chenery, H., Srinivasan, T.N., Streeten, P., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 1988; pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, G. Sustainable tourism—Unsustainable development. In Tourism, Development and Growth: The Challenge of Sustainability; Wahab, S., Pigram, J.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Mtapuri, O. Community-based tourism: An exploration of the concept(s) from a political perspective. Tour. Rev. Int. 2012, 16, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. Addressing the measurement of tourism in terms of poverty reduction: Tourism value chain analysis in Lao PDR and Mali. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 16, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaye, J. Understanding Community Development. Available online: http://vibrantcanada.ca/files/understanding_community_development.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- Seers, D. The Meaning of Development; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, D. Measuring the Changing Quality of the World’s Poor: The Physical Quality of Life Index; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, F.; Deneulin, S. Amartya Sen’s contribution to development thinking. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2002, 37, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaurkubule, Z. Influence of quality of life on the state and development of human capital in Lativia. Contemp. Econ. 2014, 8, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Czapinski, J. Summary. Contemp. Econ. 2011, 5, 262–285. [Google Scholar]

- World Resources Institute (WRI). The Wealth of the Poor: Managing Ecosystems to Fight Poverty; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Herath, D. The discourse of development: Has it reached maturity? Third World Q. 2009, 30, 1449–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Pittman, R.H. A framework for community and economic development. In An Introduction to Community Development; Phillips, R., Pittman, R.H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, T.; Nel, E. Beyond the development impasse: The role of local economic development and community self-reliance in rural South Africa. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 1999, 37, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, T.; Nel, E. Tourism as a local development strategy in South Africa. Geogr. J. 2002, 168, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Western Australia. Community Development: A Guide for Local Government Elected Members; Department of Local Government and Communities: Perth, Australia, 2015.

- Kingsbury, D. Community development. In Key Issues in Development; Kingsbury, D., Remenyi, J., Mckay, J., Hunt, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, D.; van Dreunen, E. Leisure as a social transformation mechanism in community development practice. J. Appl. Recreat. Res. 1996, 21, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, P.; Vercseg, I. Community Development and Civil Society: Making Connections in the European Context; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, J. Theorizing community development. J. Community Dev. Soc. 2004, 34, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmendorf, W.F.; Rios, M. From environmental racism to civic environmentalism: Using participation and nature to develop capacity in the Belmont neighbourhood of West Philadelphia. In Partnerships for Empowerment: Participatory Research for Community-Based Natural Resource Management; Wilmsen, C., Elmendorf, W.F., Fisher, L., Ross, J., Sarathy, B., Wells, G., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008; pp. 69–103. [Google Scholar]

- Aref, F.; Gill, S.S.; Aref, F. Tourism development in local communities: As a community development approach. J. Am. Sci. 2010, 6, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R. Exploring the tourism-poverty nexus. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Rivera, M. Poverty Alleviation through Tourism Development: A Comprehensive and Integrated Approach; Apple Academic: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organisation (WTO). Tourism and Poverty Alleviation: Recommendations for Action; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). No Poverty: Why It Matters? 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 14 July 2017).

- Commission for Africa. Our Common Interest: Report of the Commission for Africa. 2005. Available online: http://www.commissionforafrica.info/wp-content/uploads/2005-report/11-03-05_cr_report.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Sumner, A. Meaning versus measurement: Why do economic indicators of poverty still predominate? Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, F.; Chakravarty, S.R. The measurement of multidimensional poverty. J. Econ. Inequal. 2003, 1, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, A. Economic Well-Being and Non-Economic Well-Being: A Poverty of the Meaning and Measurement of Poverty. 2004. Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/rp2004-030.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- Townsend, P. What is Poverty? An Historic Perspective; United Nations Development Programme International Poverty Centre: Brasilia, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). The Millennium Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Gender Mainstreaming in Poverty Eradication and the Millennium Development Goals: A Handbook for Policy-Makers and Other Stakeholders; Common Wealth Secretariat International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S. The Meaning and Measurement of Poverty. 1999. Available online: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/3095.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- Chambers, R. Rural Poverty Unperceived; Longman: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank (WB). World Development Report; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Rights and agency. Philos. Public Aff. 1982, 11, 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. A sociological approach to the measurement of poverty: A reply to Professor Peter Townsend. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 1985, 37, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Food and Freedom. 1987. Available online: http://archive.wphna.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/1985-Sen-Food-and-freedom.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report 2016: Human Development for Everyone; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Noorbakhsh, F. A modified human development index. World Dev. 1998, 26, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M. Poverty and People’s Wellbeing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Follow-Up to the Millennium Development Goals: Opportunities and Challenges for National Statistical Systems. 2005. Available online: http://www.cepal.org/deype/ceacepal/documentos/lcl2319i.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2017).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Technical Notes: Calculating the Human Development Indices-Geographical Presentation. 2016. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2016_technical_notes.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2017).

- United Nations (UN). The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kamruzzaman, P. Dollarisation of Poverty: Rethinking Poverty Beyond 2015; Palgrave MacMillan: Hampshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spicker, P.; Leguizamon, S.A.; Gordon, D. Poverty: An International Glossary; Zed Books: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2017).

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals Brochure; United Nations World Tourism Organisation: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Faux, J. Tripple bottom line reporting of tourism organisations to support sustainable development. In Understanding the Sustainable Development of Tourism; Liburd, J.J., Edwards, D., Eds.; Goodfellow: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet 2012, 379, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slapper, T.F.; Hall, J.T. The triple bottom line: What is it and how does it work? Indian Bus. Rev. 2011, 86, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Brende, B.; Høie, B. Towards evidence-based, quantitative sustainable development goals for 2030. Lancet 2015, 385, 206–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davis, A.; Matthews, Z.; Szabo, S.; Fogstad, H. Measuring the SDGs: A two-track solution. Lancet 2015, 386, 221–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hák, T.; Janoušková, S.; Moldan, B. Sustainable development goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, N. World Poverty; Thomson Gale: Detroit, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, P.; Tsumori, K. Poverty in Australia: Beyond the rhetoric. Policy Monograph; The Centre for Independent Studies: Sydney, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). The Millennium Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S.; Sangraula, P. Dollar a day revisited. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2009, 23, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.; Seth, S.; Lokshin, M.; Sajaia, Z. A Unified Approach to Measuring Poverty and Inequality: Theory and Practice; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Report of the Secretary General. 2016. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=E/2016/758Lang=E (accessed on 6 July 2017).

- Wilson, C.; Wilson, P. Make Poverty Business: Increase Profits and Reduce Risks by Engaging with the Poor; Greenleaf: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, A.; Sonne, J.; Novelli, M. Tourism and poverty reduction: An interpretation by the poor of Elmina, Ghana. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2011, 8, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, P. The Ethical Poverty Line: A Moral Definition of Absolute Poverty; United Nations Development Programme International Poverty Centre: Brasilia, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Freistein, K.; Koch, M. The Effects of Measuring Poverty Indicators of the World Bank. 2014. Available online: https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/download/2651916/2651917 (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- The World Bank (WB). World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Poverty; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, A. Falling into poverty: Other side of poverty reduction. Econ. Political Wkly. 2003, 38, 533–542. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Roberto, N.; Leisner, T. Alleviating poverty: A macro/micro marketing perspective. J. Macromark. 2006, 26, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, T. No end to poverty. J. Dev. Stud. 2007, 43, 929–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E. Rethinking poverty alleviation: A “poverties” approach. Dev. Pract. 2008, 18, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditch, J. Introduction to Social Security: Policies, Benefits, and Poverty; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel, J.; van der Duim, R. Tourism and development at work: 15 years of tourism and poverty reduction within the SNV Netherlands Development Organisation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A.; Meyer, D. Tourism and poverty reduction: Theory and practice in less economically developed countries. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kadt, E. Tourism Passport to Development? Perspectives on the Social and Cultural Effects of Tourism in Developing Countries; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Telfer, D.J. The evolution of tourism and development theory. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Sharpley, R., Telfer, D.J., Eds.; Channel View: Clevedon, UK, 2002; pp. 35–78. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, J.R. Pro-poor tourism poverty alleviation techniques of the 21st century: Critique. A Worldw. Stud. J. Politics 2014, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Graburn, N.H.H.; Jafari, J. Introduction: Tourism social science. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, N. Mass tourism: Benefits and costs. In Tourism, Development and Growth: The Challenge of Sustainability; Wahab, S., Pigram, J.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 44–69. [Google Scholar]

- Budeanu, A. Impacts and responsibilities for sustainable tourism: A tour operator’s perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbinah, P.B. Contextualising the meaning of ecotourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature Friends International. What is Sustainable Tourism? 2008. Available online: http://www.nfi.at/dmdocuments/NachhaltigerTourismus_EN.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2017).

- Prince, S.; Ioannides, D. Contextualizing the complexities of managing alternative tourism at community-level: A case study of a nordic eco-village. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Chatterjee, B. Ecotourism: A panacea or predicament? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Timothy, D.J.; Dowling, R.K. Tourism and destination communities. In Tourism in Destination Communities; Singh, S., Timothy, D.J., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; CABI: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kontogeorgopoulos, N. Community-based ecotourism in Phuket and Ao Phangnga, Thailand: Partial victories and bittersweet remedies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 1391, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.; Wiltshier, P. Community tourism. In Research Themes for Tourism; Robinson, P., Heitmann, S., Dieke, D.P., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- The World Tourism Organisation. Charter for Sustainable Tourism. 1995. Available online: http://www.institutoturismoresponsable.com/events/sustainabletourismcharter2015/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/CharterForSustainableTourism.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- United Nations. Promotion of Sustainable Tourism, Including Ecotourism, for Poverty Eradication and Environment Protection. 2015. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/787314?ln=en#record-files-collapse-header (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Giampiccoli, A.; Kalis, H.J. Community-based tourism and local culture: The case of the amaMpondo. Posos Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2012, 10, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayaka, M.A.; Croy, G.; Mayson, S. Community-based tourism: Common conceptualisation or disagreement? In Proceedings of the 22nd CAUTHE Annual Conference organised by La Trobe University; Mayaka, M.A., Croy, G., Mayson, S., Eds.; La Trobe University: Melbourne, Australia, 2012; pp. 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti, V.G.; Font, X. Community Based Tourism: Critical Success Factors. 2013. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d2ad/be19582abbef9179f726bdbb61bf54b571eb.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M.; Jugmohan, S. Developing community-based tourism in South Africa: Addressing the missing link. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2014, 20, 1139–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, G.; Santilli, R.; Armstrong, R. Community-based tourism in the developing world: Delivering the goods? In Progress in Responsible Tourism, 3 (1); Goodwin, H., Font, X., Eds.; Goodfellow: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M. A conceptualisation of alternative forms of tourism in relation to community development. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhartiya, S.P.; Masoud, D. Community based tourism: A trend for socio-cultural development and poverty lessening. Glob. J. Res. Anal. 2015, 26, 348–350. [Google Scholar]

- Jugmohan, S.; Steyn, J.N. A pre-condition evaluation and management model for community-based tourism. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2015, 21, 1065–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, N.B. Community-based cultural tourism: Issues, threats and opportunities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtapuri, O.; Giampiccoli, A. Towards a comprehensive model of community-based tourism development. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2016, 98, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Mtapuri, O. Between theory and practice: A conceptualization of community based tourism and community participation. Loyola J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 29, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Lindo, P.; Vanderchaeghe, M. Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C. Tourism, Communities, and the Potential Impacts on Local Incomes and Conservation (10); Ministry of Environment and Tourism: Windhoek, Namibia, 1995.

- Saayman, M.; Giampiccoli, A. Community-based tourism and pro-poor tourism: Dissimilar positioning in relation to community development. J. New Gener. Sci. 2015, 13, 116–181. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, M.C. Community benefit tourism initiatives—A conceptual oxymoron? Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Tourism and community development issues. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Sharpley, R., Telfer, D.J., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2002; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. Community-based ecotourism: The significance of social capital. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, R.; Cooke, F.M.; Kunjuraman, V. Community-based ecotourism (CBET) activities in Abai Village, lower Kinabatangan area of Sabah, east Malaysia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Natural Resources, Tourism and Services Management Organised by Universiti Putra Malaysia; Mahdzar, M., Ling, S.M., Nair, M.B., Shuib, A., Eds.; Universiti Putra Malaysia: Serdang, Malaysia, 2015; pp. 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, M. The Community Tourism Guide: Exciting Holidays for Responsible Travellers; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R.; Gursoy, D.; YolaL, M.; Lee, T. Community based tourism-lessons learned for knowledge mobilisation. In The 5th Advances in Hospitality & Tourism Marketing and Management (AHTMM) Conference organised by Asia Pacific University; Gursoy, R., Yolal, M., Lee, T., Eds.; Washington State University: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zeppel, H. Indigenous Ecotourism: Sustainable Developed and Management; CABI: Sidney, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.; Chang, J.; Huan, T.C. The Aboriginal people of Taiwan: Discourse and silence. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples: Issues and Implications; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 188–202. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, M.J. Rural tourism and rural development. In Tourism and the Environment: Regional, Economic and Policy Issues; Briassoulis, H., van der Straaten, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Tourism Strategies and Rural Development. 1994. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/tourism/2755218.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2016).

- Barkauskas, V.; Barkauskiene, K.; Jasinskas, E. Analysis of macro environmental factors influencing the development of rural tourism: Lithuanian case. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujadhur, T. Organisations and Their Approaches in Community Based Natural Resources Management in Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe; IUCN: Gaberone, Botswana, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B. Commons Southern Africa 7: CBNRM, Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Livelihoods: Developing Criteria for Evaluating the Contribution of CBNRM to Poverty Reduction and Alleviation in Southern Africa; Centre for Applied Social Sciences: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hoole, A. Lessons from the Equator Initiative: Common Property Perspectives for Community-Based Conservation in Southern Africa and Namibia; Centre for Community-Based Resource Management-Natural Resource Institute-University of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, M.; Gilpin, R. Tourism in the Developing World: Promoting Peace and Reducing Poverty; United States Institute of Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Mawere, M.; Mubaya, T. The role of ecotourism in the struggles for environmental conservation and development of host communities in developing economies: The case of Mtema Ecotourism Centre in South-eastern Zimbabwe. J. Res. Peace Gend. Dev. 2012, 2, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D.; Schipani, S. Lao tourism and poverty alleviation: Community-based tourism and the private sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 194–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Building community capacity for tourism development: Conclusion. In Building Community Capacity for Tourism Development; Moscardo, G., Ed.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2008; pp. 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, E. A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtapuri, O.; Giampiccoli, A. Interrogating the role of the state and nonstate actors in community-based tourism ventures: Towards a model of spreading the benefits to the wider community. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2013, 95, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Jugmohan, S.; Mtapuri, O. Community-based tourism in rich and poor countries: Towards a framework for comparison. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2015, 21, 1200–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.; Muckosy, P. A Misguided Quest: Community-Based Tourism in Latin America; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Balint, P.J.; Mashinya, J. Campfire during Zimbabwe’s national crisis: Local impacts and broader implications for community-based wildlife management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeyre, R. Community-based tourism as a sustainable solution to maximise impacts locally? The Tsiseb Conservancy case, Namibia. Dev. South. Afr. 2010, 27, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R. An analysis of the conditions for success of community based tourism enterprises. ICRT Occas. Pap. 2012, 21, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, A. Tourism, Poverty and Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pleumarom, A. The Politics of Tourism, Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Development; Third World network (TWN): Penang, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D. Pro-poor tourism: A critique. Third World Q. 2008, 29, 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Roe, D.; Goodwin, H. Pro-Poor Tourism Strategies: Making Tourism Work for the Poor: A Review of Experience; International Institute for Environment and Development: Nottingham, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chok, S.; Macbeth, J.; Warren, C. Tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation: A critical analysis of pro-poor tourism and implications for sustainability. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriade, A.; Evans, M. Sustainable and alternative tourism. In Research Themes in Tourism; Robinson, P., Heitmann, S., Dieke, P., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schilcher, D. Growth versus equity: The continuum of pro-poor tourism and neoliberal governance. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Pro-poor tourism: Is there value beyond the rhetoric? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2009, 34, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D. Tourism and Poverty Alleviation: A Case Study of Sapa, Veitnam. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canterbury, Canterbury, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, V.D.; Hall, C.M.; Garry, T. Tourism and poverty alleviation: Perceptions and experiences of poor people in Sapa, Vietnam. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1071–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Pro-poor tourism: Do tourism exchanges benefit primarily the countries of the South? Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 102, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A. Environment and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic, T. Tourism and economic development issues. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Sharpley, R., Telfer, D.J., Eds.; Channel View: Clevedon, UK, 2002; pp. 81–111. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Duim, V.R.; Caalders, J. Tourism chains and pro-poor tourism development: An actor-network analysis of a pilot project in Costa Rica. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D. Pro-poor tourism: Looking backward as we move forward. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, O.; Roe, D.; Ashley, C. Sustainable Tourism and Poverty Elimination Study: A Report to the Department for International Development; Deloitte & Touche: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, D.; Khanya, P.U. Pro-poor Tourism: Harnessing the World’s Largest Industry for the World’s Poor; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saayman, M.; Giampiccoli, A. Community-based and pro-poor tourism: Initial assessment of their relation to community development. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 12, 145–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, C.; Roe, D. Enhancing Community Involvement in Wildlife Tourism: Issues and Challenges; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.; Ashley, C. Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Pathways to Prosperity; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D. Pro-poor tourism—Can tourism contribute to poverty reduction in less economically developed countries? In Tourism and Inequality: Problems and Prospects; Cole, S., Morgan, N., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H. Measuring and Reporting the Impact of Tourism on Poverty: Cutting Edge Research in Tourism-New Directions, Challenges and Applications; University of Surrey: Guildford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, M.C. An integrated approach to assess the impact of tourism on community development and sustainable livelihoods. Community Dev. J. 2007, 44, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, J.; Gujadhur, T.; Ritsma, N. Evolution of tourism approaches for poverty reduction impact in SNV Asia: Cases from Lao PDR, Bhutan and Vietnam. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R. The role of tourism in poverty reduction: An empirical assessment. Tour. Econ. 2014, 20, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón, J. Pro-poor tourism as a strategy to fight rural poverty: A critique. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, C.; Cukier, J. Is tourism employment as sufficient mechanism for poverty reduction? A case study from Nkhata Bay, Malawi. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A.; Habyalimana, S.; Tusabe, R.; Mariza, D. Benefits to the poor from gorilla tourism in Rwanda. Dev. South. Afr. 2010, 27, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Weppen, J.; Cochrane, J. Social enterprises in tourism: An exploratory study of operational models and success factors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J. Value chain approaches to assessing the impact of tourism on low-income households in developing countries. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M. Tourism-agriculture linkages in rural South Africa: Evidence from the accommodation sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Russel, M. Tourism and poverty alleviation in Fiji: Comparing the impacts of small- and large–scale tourism enterprises. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahebwa, W.M.; van der Dium, R.; Sandbrook, C. Tourism revenue sharing policy at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda: A policy arrangements approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, F. Blessing or curse? The political economy of tourism development in Tanzania. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzt, L. The Sustainable Livelihood Approach to Poverty Reduction. 2001. Available online: https://www.sida.se/contentassets/bd474c210163447c9a7963d77c64148a/the-sustainable-livelihood-approach-to-poverty-reduction_2656.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2018).

- Truong, V.D.; Liu, X.; Pham, Q. To be or not to be formal? Rickshaw drivers’ perspectives on tourism and poverty. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 28, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbabwe-Info. Manicaland. 2018. Available online: https://www.zimbabwe-info.com/country/province/73/manicaland (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Dube, L.; Guveya, E. Technical efficiency of smallholder out-grower tea (Camellia sinensis) farming in Chipinge district of Zimbabwe. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 4, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revolvy. Manicaland Province. 2018. Available online: https://www.revolvy.com/page/Manicaland-Province (accessed on 11 March 2019).

- Pindula. Manicaland Province. 2018. Available online: https://pindula.co.zw/Manicaland_Province (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- The standard. Poor Roads Inhibit Tourism Growth in Eastern Highlands. 2012. Available online: https://www.thestandard.co.zw/2012/09/23/poor-roads-inhibit-tourism-growth-in-eastern-highlands/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Central Statistics Office (CSO). Poverty. 2007. Available online: http://www.zimstat.co.zw/sites/default/files/img/publications/Finance/Poverty_2001.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). Poverty and Poverty Datum Line Analysis in Zimbabwe 2011/12. 2013. Available online: http://www.zw.undp.org/content/dam/zimbabwe/docs/Governance/UNDP_ZW_PR_Zimbabwe%20Poverty%20Report%202011.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2017).

- United Nations Children’s Fund Zimbabwe (UNICEF); The World Bank(WB); Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). Zimbabwe Poverty Atlas: Small Area Poverty Estimation: Statistics for Poverty Eradication. 2015. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/Zimbabwe_Poverty_Atlas_2015.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2017).

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). Zimbabwe Poverty Atlas. 2015. Available online: http://www.zimstat.co.zw/sites/default/files/img/publications/Finance/Poverty_Atlas2015.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2017).

- Nyangani, K. Bad Roads Affect Tourism in Manicaland. Newsday, 27 February 2018. Available online: https://www.newsday.co.zw/2018/02/bad-roads-affect-tourism-manicaland/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Our Airports. Airports in Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe. 2016. Available online: http://ourairports.com/countries/ZW/MA/airports.html (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA). Overview of Tourism Performance in Zimbabwe. 2017. Available online: http://www.zimbabwetourism.net/tourism-trends-statistics/?cp_tourism-trends-statistics=1 (accessed on 8 September 2018).

- Abel, S.; Le Roux, P. Tourism an engine of wealth creation in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Tambo, B. Tourism Receipts in Zimbabwe: Are These Low Hanging Fruits Benefiting the Country’s Economy? The Sunday News, 25 June 2017. Available online: http://www.sundaynews.co.zw/tourism-receipts-in-zimbabwe-are-these-low-hanging-fuits-benefiting-the-countrys-economy/ (accessed on 12 September 2017).

- Zimbabwe Expeditions. Inn On Rupurura Closed Due to Decline in Tourist Arrivals in Nyanga Region. 2017. Available online: http://zimbabwe-expeditions.blogspot.com/2017/05/inn-on-rupurara-closed-due-to-decline.html (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- High, J. The Zimbabwe Mountain Guide Training Course. 2017. Available online: www.chimanimani.com/the-zimbabwe-mountain-guide-training-course/ (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Qualitative Research Guidelines Project, Opportunistic or Emergent Sampling. 2008. Available online: www.qualres.org/HomeOpp.3815.html/ (accessed on 27 September 2016).

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marvasti, A. Qualitative Research in Sociology: An Introduction; Sage: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Monica, E. Consent Process for Illiterate Research Participants. 2012. Available online: https://kb.wisc.edu/hsirbs/page.php?id=27051 (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Yin, R.K. Applications of Case Study Research; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Christians, C.G. Ethics and politics in qualitative research. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 139–164. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, J.; Spire, Z. The role of informal conversations in generating data, and the ethical and methodological issues they raise. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Election Resource Centre (ERC). Manicaland Province. 2016. Available online: https://erczim.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/MANICALAND-PROVINCE-ERC-CON-PROFILE.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Ministry of Tourism and Hospitality Industry (MoTHI). Zimbabwe National Tourism Master Plan; Keios Development Consulting: Roma, Italy, 2016.

- Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ); MoTHI Ministry of Tourism and Hospitality Industry (MoTHI); Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Community-Based Tourism Master Plan Targeting Poverty Alleviation in the Republic of Zimbabwe: Final Report Appendix. 2017. Available online: http://open_jicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12288759.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Mitchell, J.; Ashley, C. Pathways to Prosperity—How Can Tourism Reduce Poverty: A Review of Pathways, Evidence and Methods; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organisation (WTO). Tourism and Poverty Alleviation; The World Tourism Organisation: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Enemuo, O.B.; Oyinkansola, O.C. Social impact of tourism development in host communities of Osun Oshogbo sacred grove. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.H. A proto-CAMPFIRE Initiative in Mahenye Ward, Chipinge District: Development of Wildlife Utilisation Programme in Response to Community Needs; Centre for Applied Social Sciences: Harare, Zimbabwe, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Murphree, M.W. The lesson from Mahenye. In Endangered Species Threatened Convention: The Past, and Future of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora; Hutton, J., Dickson, B., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA). An Audit of Community-Based Tourism Projects in Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe (Unpublished); Zimbabwe Tourism Authority: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Manwa, H. Wildlife-based tourism, ecology and sustainability: A tug of war among competing interests in Zimbabwe. J. Tour. Stud. 2003, 14, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, R.M.; Harris, R.W.; Vogel, D.R. E-Commerce for Community-Based Tourism in Developing Countries. Paper presented at the 9th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Bankok, Thailand, 27 February 2005; Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.594.3553&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Reino, S.; Frew, A.J.; Albacete-Saez, C. ICT adoption and development: Issues in rural accommodation. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2011, 2, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, A.S.P.; Jamilena, D.M.F.; Molina, M.A.R. Impact of customer orientation and ICT use on the perceived performance of rural tourism enterprises. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.T.B.; Diggle, R.W.; Thouless, C. From exploitation to ownership: Wildlife-based tourism and communal area conservancies in Namibia. In Institutional Arrangements for Conservation, Development and Tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Dynamic Perspective; van der Dium, R., Lamers, M., van Wijk, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R. Tourism and Poverty; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaiwa, J.E. Community-based natural resource management in Botswana. In Institutional Arrangements for Conservation, Development and Tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Dynamic Perspective; van der Duim, R., Lamers, M., van Wijk, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lejarraga, I.; Walkenhorst, P. On linkages and leakages: Measuring the secondary effects of tourism. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2010, 17, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, A.F. Tourism for Poverty Reduction in South Asia. What Works and Where Are the Gaps; DFID: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Easterly, W. The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Period | Concept of Poverty | Measurement of Poverty |

|---|---|---|

| 1950s | Economic | GDP growth |

| 1960s | Economic | Per capita GDP growth |

| 1970s | Basic needs including economic | Per capita GDP growth plus basic needs |

| 1980s | Economic and capabilities | Per capita GDP and rise of non-monetary factors |

| 1990s | Human development and economic | UNDP Human Development Indices |

| 2000–2015 | Multidimensional (rights, freedom, livelihoods) | Millennium Development Goals Multidimensional Poverty Index |

| 2016 to present | Multidimensional | Sustainable Development Goals Multidimensional Poverty Index |

| Chipinge | Mutasa | Buhera | Chimanimani | Nyanga | Makoni | Mutare |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 86.2% | 78.9% | 78% | 76% | 73.7% | 68.2% | 60.7% |

| Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total rooms | 671 | 671 | 696 | - | 714 | 714 | 714 | 781 | 781 | 781 | 781 | 781 | 781 |

| Total beds | 1350 | 1350 | 1511 | - | 1389 | 1389 | 1389 | 1535 | 1535 | 1535 | 1535 | 1535 | 1535 |

| Year | Nyanga National Park | Chimanimani National Park | Vumba Botanical Gardens | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | International | Domestic | International | Domestic | International | ||

| 1999 | 15,327 | 2601 | 6200 | 5151 | 9281 | 4214 | 42,774 |

| 2000 | 20,471 | 1006 | 2979 | 909 | 7840 | 3425 | 16,159 |

| 2001 | 26,620 | 836 | 4670 | 1215 | 5769 | 1637 | 40,747 |

| 2002 | 20,428 | 424 | 1656 | 189 | 2039 | 268 | 25,004 |

| 2003 | 18,812 | 11 | - | - | - | - | 18,823 |

| 2004 | 1,525,040 | 65 | - | - | - | - | 1,525,105 |

| 2005 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2006 | 12,142 | - | 805 | - | 2011 | - | 14,958 |

| 2007 | 12,330 | - | 419 | - | 1880 | - | 14,629 |

| 2008 | 17,947 | - | - | - | 3526 | - | 21,473 |

| 2009 | 11,792 | - | 1427 | - | 1322 | - | 14,541 |

| 2010 | 11,158 | - | 877 | - | 1937 | - | 13,972 |

| 2011 | - | - | 2324 | - | 2136 | - | 4460 |

| 2012 | 21,454 | 416 | 535 | - | 3172 | 396 | 26,973 |

| 2013 | 1704 | 85 | 1997 | 405 | 2473 | 337 | 7001 |

| 2014 | 23,882 | 598 | 3383 | 666 | 3074 | 399 | 32,002 |

| 2015 | 20,675 | 467 | 4712 | 662 | 3405 | 412 | 30,333 |

| Name Pseudonym | Gender | Age | Location/District | Activity/Employment | Name pseudonym | Gender | Age | Location/District | Activity/Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoko | Male | 30 | Chipinge | Unemployed | Mombe | Male | 33 | Chimanimani | Unemployed |

| Danda | Male | 43 | Chipinge | Informally employed | Gonzo | Male | 22 | Chimanimani | Employed |

| Gore | Male | 31 | Chipinge | Unemployed | Nyundo | Male | 22 | Nyanga | Employed |

| Madhuve | Female | 27 | Chipinge | Employed | Bveni | Male | 45 | Mutare | Informally employed |

| Inzwi | Male | 46 | Chipinge | Informally employed | Gejo | Male | 41 | Nyanga | Informally employed |

| Tino | Male | 46 | Chipinge | Employed | Chiwepu | Male | 31 | Nyanga | Employed |

| Taku | Male | 49 | Chipinge | Unemployed | Zumbu | Male | 53 | Nyanga | Unemployed |

| Piki | Male | 83 | Chipinge | Unemployed | Nzungu | Male | 30 | Nyanga | Unemployed |

| Feso | Male | 38 | Chipinge | Employed | Zviso | Female | 50 | Nyanga | Informally employed |

| Hombarume | Male | 39 | Chipinge | Informally employed | Chenai | Female | 33 | Nyanga | Employed |

| Gweta | Male | 53 | Chipinge | Employed | Tsoro | Male | 52 | Nyanga | Informally employed |

| Muwuyu | Male | 45 | Chimanimani | Employed | Tombi | Female | 76 | Nyanga | Unemployed |

| Tsubvu | Male | 48 | Mutare | Unemployed | Mufudzi | Male | 31 | Chimanimani | Employed |

| Zino | Male | 55 | Chimanimani | Unemployed | Shanje | Female | 43 | Nyanga | Unemployed |

| Saka | Male | 43 | Chimanimani | Informally employed | Mbudzi | Male | 52 | Mutare | Unemployed |

| Chipikiri | Male | 18 | Chimanimani | Employed | Huku | Male | 46 | Chipinge | Unemployed |

| Muti | Male | 33 | Mutare | Informally employed | Hwai | Female | 37 | Chipinge | Employed |

| Gonhi | Female | 38 | Mutare | Informally employed | Katsi | Male | 43 | Mutare | Informally employed |

| Tsvimbo | Male | 55 | Mutare | Unemployed | Juru | Male | 32 | Nyanga | Employed |

| Svodai | Female | 32 | Chimanimani | Unemployed | Svosve | Male | 28 | Mutare | Unemployed |

| Rukova | Female | 38 | Chimanimani | Unemployed | |||||

| Sango | Male | 37 | Chimanimani | Informally employed | |||||

| Vende | Male | 50 | Chimanimani | Unemployed |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gohori, O.; van der Merwe, P. Towards a Tourism and Community-Development Framework: An African Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135305

Gohori O, van der Merwe P. Towards a Tourism and Community-Development Framework: An African Perspective. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135305

Chicago/Turabian StyleGohori, Owen, and Peet van der Merwe. 2020. "Towards a Tourism and Community-Development Framework: An African Perspective" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135305

APA StyleGohori, O., & van der Merwe, P. (2020). Towards a Tourism and Community-Development Framework: An African Perspective. Sustainability, 12(13), 5305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135305