Sustainable Financial Partnerships for the SDGs: The Case of Social Impact Bonds

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Financial Innovation for Sustainable Outcomes: An Overview

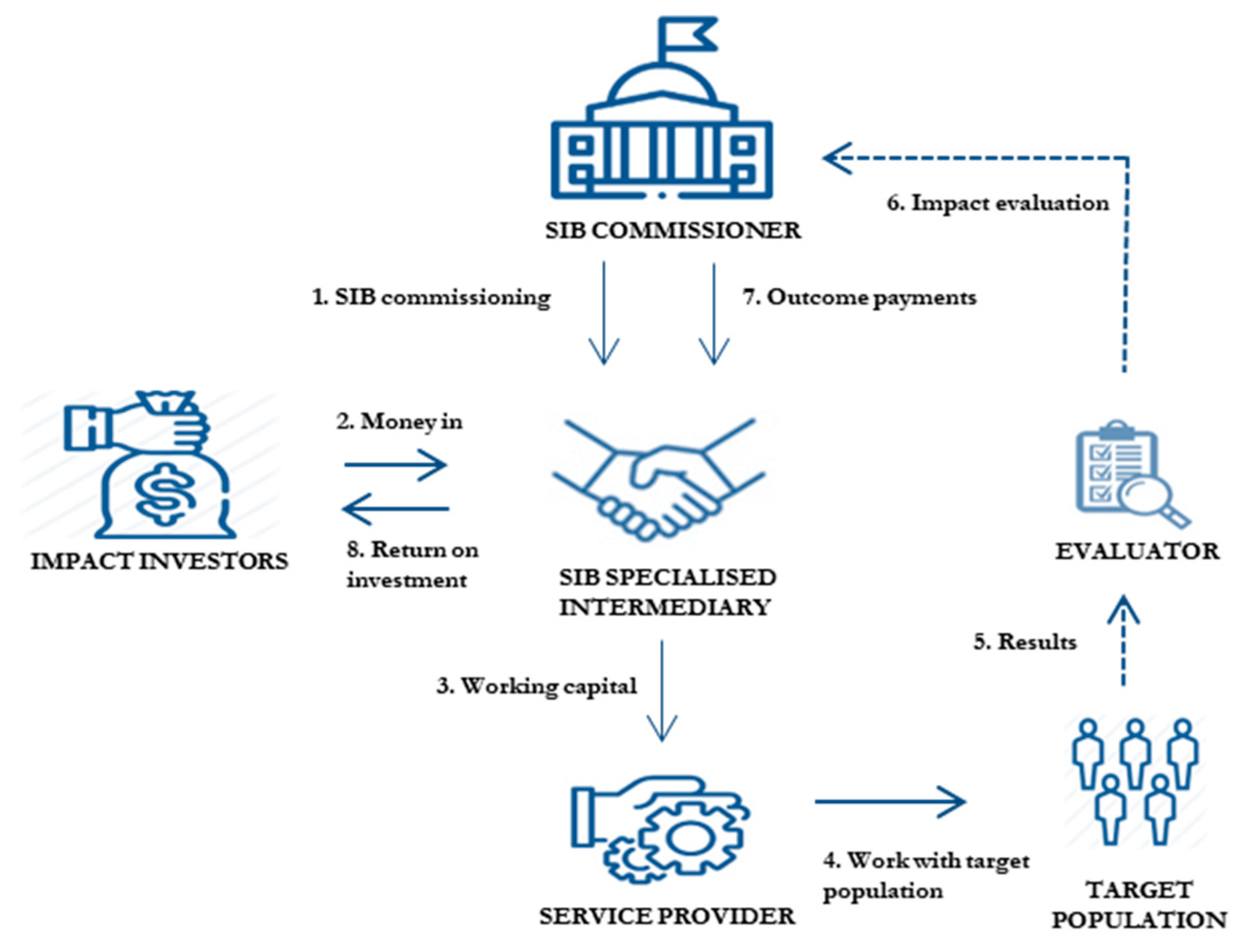

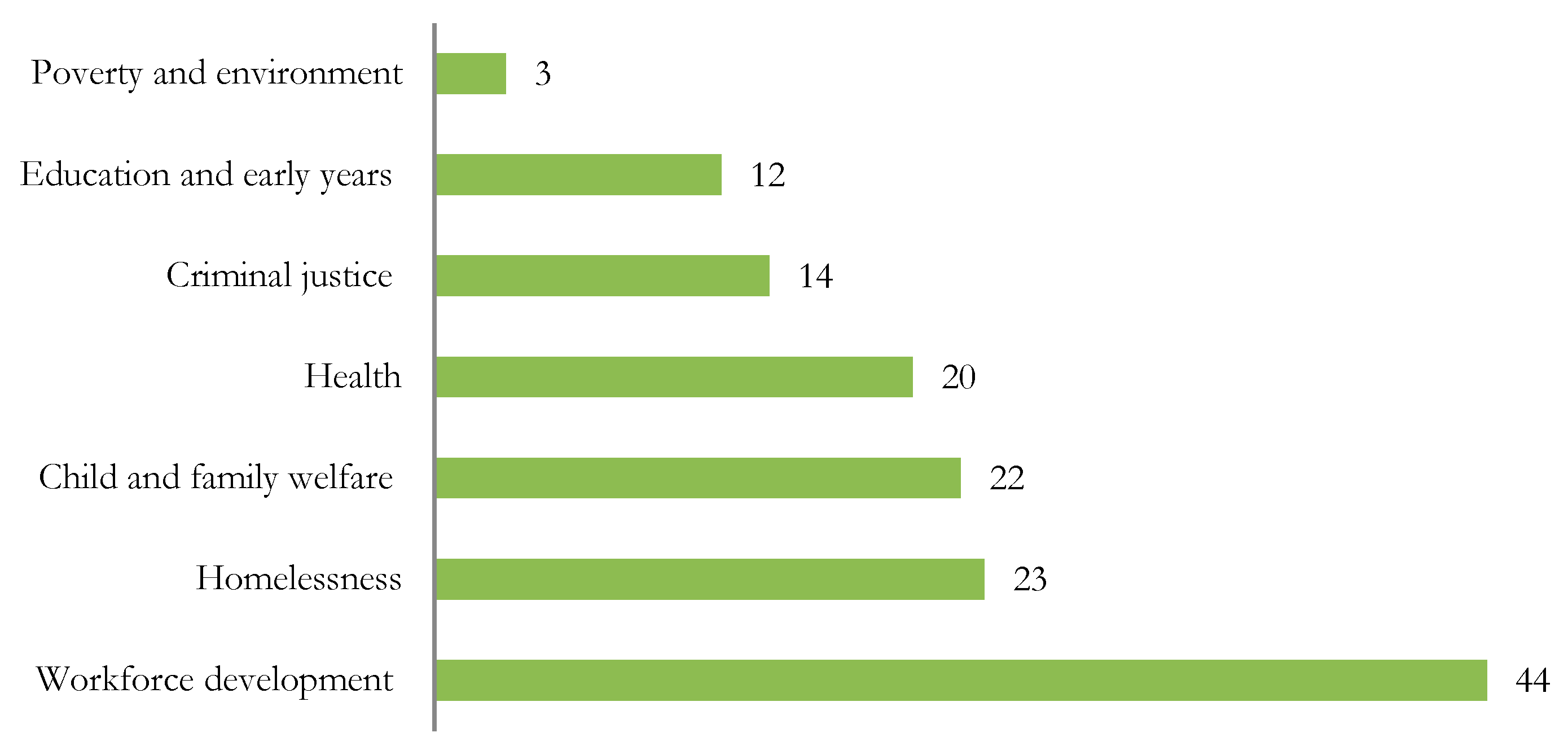

Social Impact Bonds: Collaborative Cross-Sector Partnerships for Social Outcomes

3. Methodology

3.1. Literature Review about Partnership for SDGs

3.2. Case Selection and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Case Studies

4.1. London Homelessness Social Impact Bond (St Mungo’s/Street Impact)

4.2. DWP Innovation Fund Round II - Greater Manchester (Teens and Toddlers)

4.3. Educate Girls

4.4. The Asháninka DIB

4.5. Cross-Case Analysis

4.5.1. Partnerships

4.5.2. Financial Resources

4.5.3. Social Impact

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. SDG Based Financial Partnerships: Conceptualizations and Main Distinguishing Elements Identified in Literature

5.2. Comparison between SIB and SDG-Based Financial Partnerships

5.3. Design of SDG-Based Investment Partnership with SIBs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trabacchi, C.; Buchner, B. Unlocking Global Investments for SDGs and Tackling Climate Change. In Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through Sustainable Food Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy. Social and Solidarity Economy and the Challenge of Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: http://unsse.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Position-Paper_TFSSE_Eng1.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2020).

- Utting, P. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through Social and Solidarity Economy: Incremental versus Transformative Change. UNIRSD. 2018. Available online: http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/(httpAuxPages)/DCE7DAC6D248B0C1C1258279004DE587/$file/UNTFSSE---WP-KH-SSE-SDGs-Utting-April2018.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Fatemi, A.M.; Fooladi, I.J. Sustainable finance: A new paradigm. Glob. Financ. J. 2013, 24, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolo, M.; Fidanoski, F.; Simeonovski, K.; Filipovski, V.; Jovanovska, K. Sustainable finance role in creating conditions for sustainable economic growth and development. In Sustainable Economic Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 187–211. [Google Scholar]

- Soppe, A. Sustainable finance as a connection between corporate social responsibility and social responsible investing. Indian Sch. Bus. Wp Indian Manag. Res. J. 2009, 1, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.S. The Microfinance Revolution: Sustainable Finance for the Poor; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, O.; Duan, Y. Socially responsible finance and investing: Financial institutions, corporations, investors, and activists. In Social Finance and Banking; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 160, p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, O.; Remer, S. Social Banks and the Future of Sustainable Finance; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Belleflamme, P.; Lambert, T.; Schwienbacher, A. Individual crowdfunding practices. Ventur. Cap. 2013, 15, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, O. The New Universe of Green Finance: From Self-Regulation to Multi-Polar Governance. 2007. Available online: http://www.biu.ac.il/law/unger/wk_papers.html (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Paranque, B.; Pérez, R. “Finance Reconsidered: New Perspectives for a Responsible and Sustainable Finance”, Finance Reconsidered: New Perspectives for a Responsible and Sustainable Finance (Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance and Sustainability); Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016; Volume 10, pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhry, B.; Davies, S.W.; Waters, B. Investing for impact. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 864–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Hockerts, K. Impact investing: Review and research agenda. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2019, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, K.; Fox, C. Payment by Results and Social Impact Bonds: Outcome-Based Payment Systems in the UK and US; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- La Torre, M.; Trotta, A.; Chiappini, H.; Rizzello, A. Business models for sustainable finance: The case study of social impact bonds. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gustafsson-Wright, E.; Gardiner, S.; Putcha, V. The Potential and Limitations of Impact Bonds: Lessons from the First Five Years of Experience woRldwide. Global Economy and Development at Brookings. 2015. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-potential-and-limitations-of-impact-bonds-lessons-from-the-first-five-years-of-experience-worldwide/ (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Bergfeld, N.; Klausner, D.; Samel, M. Improving Social Impact Bonds: Assessing Alternative Financial Models to Scale Pay-for-Success. Annu. Rev. Policy Des. 2019, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shiller, R.J. Finance and the Good Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, F.; Meyer, M. Social Impact Bonds and the perils of aligned interests. Adm. Sci. 2018, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clifford, J.; Jung, T. Exploring and understanding an emerging funding approach. In Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Edmiston, D.; Nicholls, A. Social Impact Bonds: The Role of Private Capital in Outcome-Based Commissioning. J. Soc. Policy 2018, 47, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dey, C.; Gibbon, J. New development: Private finance over public good? Questioning the value of impact bonds. Public Money Manag. 2018, 38, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rania, F.; Trotta, A.; Carè, R.; Migliazza, M.C.; Kabli, A. Social Uncertainty Evaluation of Social Impact Bonds: A Model and Practical Application. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Fraser, A.; McHugh, N.; Warner, M. Widening perspectives on social impact bonds. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2019, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainability: Designing decision-making processes for partnership capacity. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, C.; Santulli, R.; Tipaldi, R. Development impact bonds to overcome investors-services providers agency problems: Insights from a case study analysis. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 13, 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Belt, J.; Kuleshov, A.; Minneboo, E. Development impact bonds: Learning from the Asháninka cocoa and coffee case in Peru. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2017, 28, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinckus, C. The valuation of social impact bonds: An introductory perspective with the Peterborough SIB. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2018, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Graham, C.; Himick, D. Social impact bonds: The securitization of the homeless. Account. Organ. Soc. 2016, 55, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Méndez-Suárez, M.; Monfort, A.; Gallardo, F. Sustainable Banking: New Forms of Investing under the Umbrella of the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fraser, A.; Tan, S.; Lagarde, M.; Mays, N. Narratives of promise, narratives of caution: A review of the literature on Social Impact Bonds. Soc. Policy Adm. 2018, 52, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, G.; Kiron, D.; Kruschwitz, N.; Reeves, M.; Rubel, H.; Zum Felde, A.M. Investing for a sustainable future: Investors care more about sustainability than many executives believe. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2016, 57, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ziolo, M.; Filipiak, B.Z.; Bąk, I.; Cheba, K.; Tîrca, D.M.; Novo-Corti, I. Finance, Sustainability and Negative Externalities. An Overview of the European Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4249. [Google Scholar]

- Lagoarde-Segot, T.; Martinez, E. Ecological Finance Theory: New Foundations. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3612729 (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Lagoarde-Segot, T.; Paranque, B. Finance and sustainability: From ideology to utopia. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2018, 55, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, O.M. Routledge Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lagoarde-Segot, T. Sustainable finance. A critical realist perspective. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 47, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, F.; Pellegrini, C.; Battaglia, M. The structuring of social finance: Emerging approaches for supporting environmentally and socially impactful projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, R.; Cowton, C.J. The maturing of socially responsible investment: A review of the developing link with corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 52, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, J.; Lindemane, M. Development of Investment Strategy Applying Corporate Social Responsibility. Trends Econ. Manag. 2017, 11, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoarde-Segot, T. Financing the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Duuren, E.; Plantinga, A.; Scholtens, B. ESG integration and the investment management process: Fundamental investing reinvented. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wendt, K. (Ed.) Positive Impact Investing: A Sustainable Bridge between Strategy, Innovation Change and Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Balkin, J. Investing with Impact: Why Finance Is a Force for Good; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzello, A.; Caridà, R.; Trotta, A.; Ferraro, G.; Carè, R. The use of payment by results in healthcare: A review and proposal. In Social Impact Investing beyond the SIB; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 69–113. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, C.; Albertson, K. Payment by results and social impact bonds in the criminal justice sector: New challenges for the concept of evidence-based policy? Criminol. Crim. Justice 2011, 11, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinckus, C. Financial innovation as a potential force for a positive social change: The challenging future of social impact bonds. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2017, 39, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galitopoulou, S.; Noya, A. Understanding Social Impact Bonds; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, M.E. Private finance for public goods: Social impact bonds. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2013, 16, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendeven, B.L. Social impact bonds: A new public management perspective. Financ. Contrôle Strat. 2019, NS-5. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/fcs/3119 (accessed on 5 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Goodall, E. Choosing Social Impact Bonds: A Practitioner’s Guide; Bridges Ventures: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, S.; Lehner, O.M.; Khorshid, A. A Case for an Islamic Social Impact Bond. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2702507 (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Scognamiglio, E.; Di Lorenzo, E.; Sibillo, M.; Trotta, A. Social uncertainty evaluation in Social Impact Bonds: Review and framework. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 47, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.; Tomkinson, E. The Peterborough Pilot Social Impact Bond. 2015. Available online: http://eureka.sbs.ox.ac.uk/id/eprint/5929 (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Arena, M.; Bengo, I.; Calderini, M.; Chiodo, V. Social impact bonds: Blockbuster or flash in a pan? Int. J. Public Adm. 2016, 39, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nazari Chamaki, F.; Jenkins, G.P.; Hashemi, M. Social impact bonds: Implementation, evaluation, and monitoring. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.T. Evaluating social impact bonds: Questions, challenges, innovations, and possibilities in measuring outcomes in impact investing. Community Dev. 2013, 44, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, A. La Finanza Sostenibile; Giappichelli Editore: Turin, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S.; McHugh, N.; Huckfield, L.; Roy, M.; Donaldson, C. Social impact bonds: Shifting the boundaries of citizenship. Soc. Policy Rev. 2014, 26, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, N.; Sinclair, S.; Roy, M.; Huckfield, L.; Donaldson, C. Social impact bonds: A wolf in sheep’s clothing? J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2013, 21, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SIB Database. Available online: https://sibdatabase.socialfinance.org.uk/ (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Oroxom, R.; Glassman, A.; McDonald, L. Structuring and Funding Development Impact Bonds for Health: Nine Lessons from Cameroon and beyond; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/structuring-funding-development-impact-bonds-for-health-nine-lessons.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Orum, A.M. Case Study: Logic. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 1509–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Applied Social Research Methods); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GO Lab Projects Database. Available online: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/project-database/ (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstanding About Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mason, P.; Lloyd, R.; Nash, F. Qualitative Evaluation of the London Homelessness Social Impact Bond (SIB): Final Report. Department of Communities and Local Government. 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/658921/Qualitative_Evaluation_of_the_London_Homelessness_SIB.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Triodos Bank. Social Impact Bonds. 2017. Available online: https://www.triodos.co.uk/articles/2018/social-impact-bonds (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Mason, P.; Lloyd, R.; Nash, F. A Navigator Model for Addressing Rough Sleeping: Learning from the Qualitative Evaluation of the London Homelessness Social Impact Bond. Department of Communities and Local Government. 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/658939/Commissioning_Social_Impact_Bonds.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Thomas, A.; Griffiths, R.; Pemberton, A. Innovation Fund Pilots Qualitative Evaluation: Early Implementation Findings. Department for Work and Pensions. 2014. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/329168/if-pilots-qual-eval-report-880.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Bridges Fund Management. Bridges Ventures and Impetus Trust Support Teens and Toddlers Successful Bid for DWP Innovation Fund. Available online: https://www.bridgesfundmanagement.com/bridges-ventures-and-impetus-trust-support-teens-and-toddlers-successful-bid-for-dwp-innovation-fund/ (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Power2. We Are the First in the World to Meet the Outcome Target of a Social Impact Bond. Available online: https://www.power2.org/we-are-the-first-in-the-world-to-meet-the-outcome-target-of-a-social-impact-bond (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Go Lab. Case Studies: Educate Girls. 2019. Available online: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/case-studies/educate-girls/ (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Instiglio. Educate Girls Development Impact Bond: Improving Education for 18,000 Children in Rajasthan. 2015. Available online: http://instiglio.org/educategirlsdib/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/EG-DIB-Design-1.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- IDinsight. Educate Girls Development Impact Bond: Final Evaluation Report. 2018. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b7cc54eec4eb7d25f7af2be/t/5dce708f3c7fd22c0bb30f1a/1573810490043/EG_Final_reduced.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Long, G.; Clough, E.; Rietig, K. A Study of Partnerships and Initiatives Registered on the UN SDG Partnerships Platform. 2019. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21909Deliverable_SDG_Partnerships_platform_Report.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Go Lab. Case Studies: Asháninka—Peru Development Impact Bond. 2019. Available online: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/case-studies/ash%C3%A1ninka-dib/ (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Gustafsson-Wright, E.; Boggild-Jones, I.; Segell, D.; Durland, J. Impact Bonds in Developing Countries: Early Learning from the Field. Global Economy and Development at Brookings. 2017. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/impact-bonds-in-developing-countries_web.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- KIT. Autonomous and Sustainable Cocoa and Coffee Production by Indigenous Asháninka People of Peru. 2015. Available online: http://www.common-fund.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Verification_Report.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Schmidt-Traub, G.; Sachs, J.D. Financing Sustainable Development: Implementing the SDGs through Effective Investment Strategies and Partnerships. 2015. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/13c6/00f92da7e447cf34d6125d323da743f08b98.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Social Finance. The Energise and Teens Toddlers Programmes 2012–2015. 2016. Available online: https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/tt-and-adviza_report_final.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Bridges Fund Management. Teens and Toddlers Innovation: Partnering Vulnerable Young People with a Toddler to Mentor, Creating Transformational Change in the Young Person’s Life. Available online: https://www.bridgesfundmanagement.com/portfolio/teens-toddlers-innovation/ (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Salazar, V.A.; Katigbak, J.J.P. Financing the Sustainable Development Goals through Private Sector Partnership. 2016. Available online: https://think-asia.org/bitstream/handle/11540/6722/FSI-CIRSS%202016-07.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Social Impact Bonds: The Early Years. Available online: https://socialfinance.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/SIBs-Early-Years_Social-Finance_2016_Final.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Mawdsley, E. From billions to trillions’ Financing the SDGs in a world ‘beyond aid. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2018, 8, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.H.; Zusman, E.; Miyazawa, I.; Cadman, T.; Yoshida, T.; Bengtsson, M. Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): An Assessment of the Means of Implementation (MOI); Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Kanagawa, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Partnerships: Finance and Private Sector Engagement for the SDGs. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/2030-agenda-for-sustainable-development/partnerships/sdg-finance--private-sector.html (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Steiner, A. Innovative Partnerships for SDG Financing. UNDP. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/news-centre/speeches/2018/innovative-partnerships-for-sdg-financing.html (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Pineiro, A.; Dirheixh, H.; Dhar, A. Financing the Sustainable Development Goals: Impact Investing in Action. GIIN. 2018. Available online: https://thegiin.org/assets/Financing%20the%20SDGs_Impact%20Investing%20in%20Action_Final%20Webfile.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Bull, B.; Miklian, J. Towards global business engagement with development goals? Multilateral institutions and the SDGs in a changing global capitalism. Bus. Politics 2019, 21, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gundogdu, A.S. Determinants of Success in Islamic Public-Private Partnership Projects (PPPs) in the Context of SDGs. Turk. J. Islamic Econ. 2019, 6, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.H.; Shah, A. The role of private sector in the implementation of sustainable development goals. Env. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Jeong, J.; Lee, J.; Yoo, A. Mobilizing Finance for SDGs: Issues and Policy Implication. [KIEP] World Econ. Brief 2019, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L.; Roseland, M.; Seitanidi, M.M. Multi-stakeholder partnerships (SDG# 17) as a means of achieving sustainable communities and cities (SDG# 11). In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Florini, A.; Pauli, M. Collaborative governance for the sustainable development goals. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2018, 5, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pattberg, P.; Widerberg, O. Transnational multistakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Conditions for success. Ambio 2016, 45, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rosenstock, T.S.; Lubberink, R.; Gondwe, S.; Manyise, T.; Dentoni, D. Inclusive and adaptive business models for climate-smart value creation. Curr. Opin. Env. Sustain. 2020, 42, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Ricart, J.E.; Duch, A.I.; Bernardo, V.; Salvador, J.; Piedra Peña, J.; Rodríguez Planas, M. EASIER: An Evaluation Model for Public–Private Partnerships Contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andonova, L.B. The power of the public purse: Financing of global health partnerships and agenda setting for sustainability. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Env. 2018, 16, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.; Vivekadhish, S. Millennium development goals (MDGS) to sustainable development goals (SDGS): Addressing unfinished agenda and strengthening sustainable development and partnership. Indian J. Community Med. Off. Publ. Indian Assoc. Prev. Soc. Med. 2016, 41, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stibbe, D.T.; Reid, S.; Gilbert, J. Maximising the Impact of Partnerships for the SDGs; The Partnering Initiative and UN DESA: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, D.; Singer, B.; McGinley, K.; Smith, R.; Budds, J.; Gabay, M.; Satyal, P. SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals-Focus on Forest Finance and Partnerships; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Global Compact. Scaling Finance for the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdghub.com/project/scaling-finance-for-the-sustainable-development-goals-foreign-direct-investment-financial-intermediation-and-public-private-partnerships/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- United Nations Global Compact and UNEP Finance Initiative. SDG BONDS: Leveraging Capital Markets for the SDGs. Available online: https://sdghub.com/project/sdg-bonds-leveraging-capital-markets-for-the-sdgs/ (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Hamel, J.; Dufour, S.; Fortin, D. Case Study Methods; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

| SIB Name | Country | Social Area | Year of Launch | End Date | Target Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London Homelessness Social Impact Bond (St Mungo’s/Street Impact) | UK | Homelessness | 2012 | 2015 | 416 persistent rough sleepers |

| DWP * Innovation Fund Round II—Greater Manchester (Teens and Toddlers) | UK | Employment | 2012 | 2015 | 1100 disadvantaged young people |

| The Ashaninka DIB | Peru | Agriculture | Jan 2015 | Oct 2015 | 99 Asháninka families ** |

| Educate Girls | India | Education | 2015 | 2018 | 7300 children |

| SIB Actors Involved | SIB Actors’ Roles | LH SIB | T&T SIB | EG DIB | The Ashaninka DIB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commissioner | Identifies social needs and makes payment if the program is successful. | Greater London Authority | Department for Work and Pensions | Children’s Investment Fund Foundation | The Common Fund for Commodities |

| Intermediary | Bring together and reconcile the interests of the actors involved in the partnership in order to define both the transaction agreements and the raising of capital. | Triodos Bank UK | Social Finance UK | Instiglio | N/A |

| Investors | Provide the necessary resources to finance the project. | CAF Venturesome, The Orp Foundation, Department of Health Social Enterprise Investment Fund, St. Mungo’s Broadway, Big Issue Invest and Other individual investors | Bridges Ventures, Impetus-PEF, Esmee Fairbairn Foundation, CAF Venturesome, Barrow Cadbury Trust | UBS Optimus Foundation | The Schmidt Family Foundation |

| Service Provider | Provides the service to SIB beneficiaries. | St Mungo’s Broadway | Teens and Toddlers (now called Power2) | Educate Girls | Rainforest Foundation UK; Central Asháninka del Río Ene (CARE); Kemito Ene Cocoa Co-operative |

| Evaluator | Is responsible for evaluating the results obtained by the programme and communicating them to the Commissioner. | N/A | N/A | IDinsight | The Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) |

| Financial Dimension | LH SIB | T&T SIB | EG DIB | The Ashaninka DIB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Raised * | €1,341,330.00 | €894,220.00 | €301,569.75 | €100,866.53 |

| Duration (years) | 3 | 3.5 | 3 | 0.10 |

| Max Outcome Payment * | €2,682,660.00 | €3,688,657.50 | €471,342.35 | €100,866.53 ** |

| Payment Achieved * | €2,682,660.00 | €3,688,657.50 | €346,246.75 | €75,600.00 |

| Social Dimension | LH SIB | T&T SIB | EG DIB | The Ashaninka DIB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue Area | Homelessness | Employment | Education | Agriculture |

| Target population | 416 persistent rough sleepers | 1100 disadvantaged young people | 7300 children | 99 Asháninka families |

| Purpose of the intervention | Provide holistic support to help persistent rough sleepers | Support young people between 14 and 15 years of age at risk of becoming NEET in order to achieve educational and behavioural improvements | Increase the percentage of girls’ enrolment and to improve schooling for both boys and girls in an area of Rajasthan | Improve the economic situation and to increase the cocoa and coffee crops of the Asháninka farmers |

| Metrics | (i) reduction of rough sleeping; (ii) sustained stable accommodation; (iii) sustained reconnection; (iv) achievement of professional qualifications; and (v) reduction in the use of emergency services. | (i) improved school behaviour; (ii) achievement of qualifications; and (iii)occupational integration. | (i) increase in enrolment; and (ii) improve school learning. | (i) increase in the supply of Kemito Ene by 60%; (ii) increase to 600 kg/ha or more in production by at least 60% of the members; (iii) transfer of at least thirty-five tonnes of cocoa during the last year of the project; and (iv) at the end of this project, forty farmers have an area of 0.5 hectares of new coffee plantations more resistant to leaf rust |

| Impact measurement method | Quasi- experimental, validated administrative data. | Validated administrative data. | Randomised Control Trial | N/A |

| Outcome Achieved | within the threshold | within the threshold | above the threshold | below the threshold |

| Pre Assessment | Partnerships Implementation and Mid-Point Review | Evaluation and Final Review |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Main Blocks of SDG-Based Financial Partnership Activities Derived from the Literature | Correspondent SIB Actors Involved in the Activities | Case Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LH SIB | T&T SIB | The Ashaninka DIB | EG DIB | ||

| Pre assessment | |||||

| Scoping a complex social issue | Commissioner | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Identifying existing initiatives and stakeholders | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Building shared goals and metrics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Planning actions on the base of policy standards | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Partnership implementation and mid-point review | |||||

| Structuring a vision and implementation strategy | Intermediary | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Structuring the partnerships (identification of roles and responsibilities) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Mobilizing financial resources Investor | Investor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Delivering (and mid-term reviewing/revising) | Service provider | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Evaluation and final review | |||||

| Measuring | Evaluator | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Final Evaluation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Lessons Learnt | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| SIB Name | LH SIB | T&T SIB | EG DIB | The Ashaninka DIB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue Area | Homelessness | Employment | Education | Agriculture |

| SIB Intervention | The project supported 416 persistent rough sleepers in London. | The project supported approximately 1100 adolescents at risk of becoming NEET. | The project provided education for girls aged between 6 and 14. | The project supported the sustainable production of cocoa and coffee by 99 Asháninka families. |

| Target Population | 416 persistent rough sleepers | 1100 disadvantaged young people | 7300 children | 99 Asháninka families |

| Duration (months) | 36 | 42 | 36 | 10 |

| Capital Raised | €1,341,330.00 | €894,220.00 | €301,569.75 | €100,866.53 |

| Metrics | (i) reduction of rough sleeping; (ii) sustained stable accommodation; (iii) sustained reconnection; (iv) achievement of professional qualifications; and (v) reduction in the use of emergency services. | (i) improved school behavior; (ii) achievement of qualifications; and (iii)occupational integration. | (i) increase in enrolment; and (ii) improve school learning. | (i) increase in the supply of Kemito Ene by 60%; (ii) increase to 600 kg/ha or more in production by at least 60% of the members; (iii) transfer of at least thirty-five tonnes of cocoa during the last year of the project; and (iv) at the end of this project, forty farmers have an area of 0.5 hectares of new coffee plantations more resistant to leaf rust. |

| Corresponding SDGs and Relative Goals | SDG No.11—Sustainable Cities and Communities | SDG No.8—Decent Work and Economic Growth | SDG No.4—Quality Education | SDG No.2—Zero Hunger |

| Goal No.11.1: By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums | Goal No.8.6: By 2030, substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training. | Goal No.4.5: By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations. | Goal No.2.3: By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment. | |

| Corresponding SDGs and relative Goals in common for all SIBs | SDG No.17—Partnerships for the Goals Goal No.17.16: Enhance the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources, to support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals in all countries, in particular developing countries. | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rizzello, A.; Kabli, A. Sustainable Financial Partnerships for the SDGs: The Case of Social Impact Bonds. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135362

Rizzello A, Kabli A. Sustainable Financial Partnerships for the SDGs: The Case of Social Impact Bonds. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135362

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizzello, Alessandro, and Abdellah Kabli. 2020. "Sustainable Financial Partnerships for the SDGs: The Case of Social Impact Bonds" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135362

APA StyleRizzello, A., & Kabli, A. (2020). Sustainable Financial Partnerships for the SDGs: The Case of Social Impact Bonds. Sustainability, 12(13), 5362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135362