Inclusive Leadership and Education Quality: Adaptation and Validation of the Questionnaire “Inclusive Leadership in Schools” (LEI-Q) to the Italian Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- openness to the community (it carries out initiatives from within the school);

- (2)

- the school as an inclusive community (it undertakes actions to generate a shared vision, promoting participation, cooperation and dynamics of positive reflection towards diversity);

- (3)

- it is a professional learning community (it promotes training, the professional development of teachers and the creation of professional learning communities); and

- (4)

- management of teaching–learning processes (it carries out initiatives to improve and promote coordination in the teaching and learning process of teachers).

2. Methods

2.1. Statement of the Problem

2.2. Participants

2.3. Evaluation Instruments

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Revision, Translation and Adaptation to the Italian Socio-Educational Context

3.2. Content Validation

3.3. Construct Validity

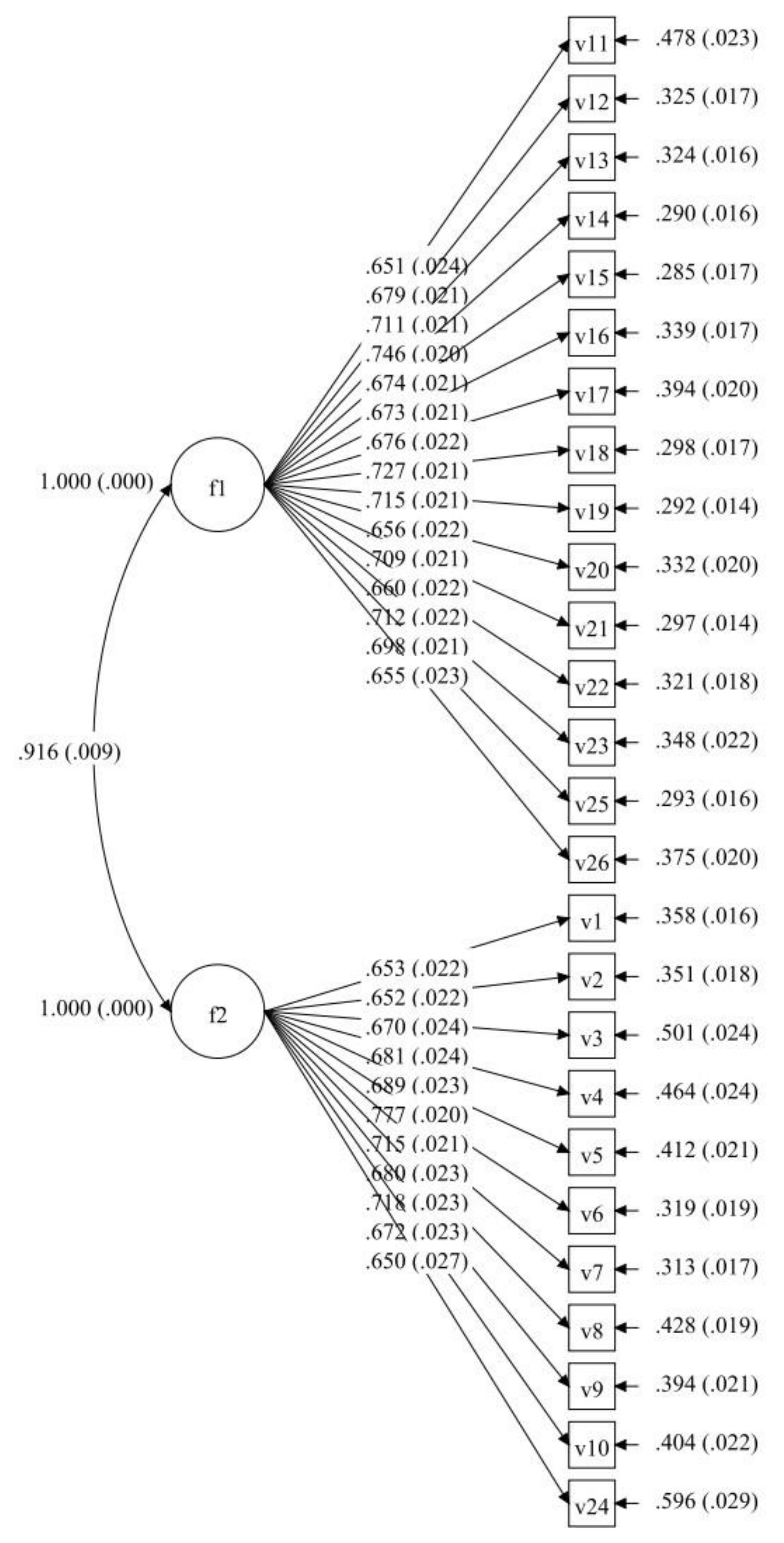

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.5. Calculation of Reliability

3.6. Differences According to Gender

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mark for each statement the box corresponding to your degree of agreement, according to your personal and/or professional criteria, based on the following scale [La preghiamo di segnare per ogni item la casella relativa ad ogni criterio secondo il grado che più concorda col suo giudizio personale e professionale, in accordo con la seguente scala]: 1. Not yet implemented [Non ancora implementato] 2. Partially implemented [Parzialmente implementato] 3. Substantially implemented [Sostanzialmente implementato] 4. Fully implemented [Pienamente implementato] |

| Dimension I. The school as an Inclusive Community [Dimensione I. La scuola come comunità inclusiva] The Management Team… [Lo Staff Di Dirigenza…] | Scale [Scala] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. It promotes initiatives that foster the participation of community members in the educational process and in the life of the school [Spinge iniziative che favoriscono la partecipazione dei membri della comunità al processo formativo e alla vita dell’ istituto] | ||||

| 2. Establishes a plan of actions, developed in collaboration with other members of the community to promote the school/community relations and respond to student diversity [Stabilisce un piano di azioni, elaborato in sinergia con altri membri della comunità, per promuovere le relazioni scuola/comunità locale e rispondere alla diversità della scolaresca] | ||||

| 3. Promotes continuous collaboration with the business world to strengthen the school-work environmental relationship [Promuove una continua collaborazione con il mondo imprenditoriale per consolidare la relazione scuola-ambiente lavorativo] | ||||

| 4. Promote actions to collaborate with other schools, to know and share experiences [Promuove azioni per collaborare con altri istituti scolastici, conoscere e condividere esperienze] | ||||

| 5. Organizes debates open to the community about situations of exclusion (racism, xenophobia, gender inequality, etc.) [Organizza dibattiti aperti alla comunità su situazioni di esclusione (razzismo, xenofobia, maschilismo)] | ||||

| 6. Participates in the actions undertaken by other education institutions/organizations of the community (sports activities, days against racism, etc.) [Participa alle azioni intraprese da altre istituzioni /organizzazioni della comunità di carattere educativo (attività sportive, giornata contro razzismo, etc.)] | ||||

| 7. Promotes actions to sensitize families on the importance and benefits of inclusion [Promuove azioni di sensibilizzazione delle famiglie sull’importanza e i benefici dell’inclusione] | ||||

| 8. Proposes educational activities outside the school [Propone attività educative fuori dall’istituto] | ||||

| 9. Establishes actions that promote the real representation of the diversity of existing families in the governing bodies of the school [Prevede iniziative che favoriscono la rappresentazione reale della diversità di famiglie esistenti negli organi di gestione dell’istituto] | ||||

| 10. Promotes activities that foster mutual knowledge, exchange and coexistence between families and other members of the school [Promuove attività che spingono la conoscenza reciproca, lo scambio e la convivenza tra le famiglie e gli altri membri dell’istituzione educative] | ||||

| 11. Establishes measures to counteract the negative influence that the family situation could have on the success of its students (campaigns to help, support for learning, schools for parents, support programmes) [Prevede misure per contrastare l’influenza negativa che la situazione familiare potrebbe avere sul successo dei suoi studenti (campagne di aiuto, sostegno all’apprendimento, incrontri con i genitori, programmi di sostegno)] | ||||

| 12. Has a procedure for collecting information on the needs of teachers, students and other school staff [Dispone di una procedura di raccolta di informazione sulle necessità del corpo docente, della scolaresca e del resto del personale dell’istituto] | ||||

| Dimension II. Management of teaching and learning processes and professional development of teachers [dimensione ii. gestione dei processi di insegnamento-apprendimento e di sviluppo professionale degli insegnanti] The management team… [lo staff di dirigenza…] | Scale [Scala] | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 13. Enables the different members of the educational community to participate in the evaluation of management tasks [Permette ai diversi membri della comunità educativa di partecipare alla valutazione dei compiti di gestione] | ||||

| 14. Establishes mechanisms to promote the participation of students in the regulation of conflicts that arise in the school environment [Promuove meccanismi per stimolare la partecipazione della scolaresca nella regolazione di conflitti che sorgono nell’ambiente educativo] | ||||

| 15. Encourages the students to express freely their opinion and needs (regarding their educational process, standards and operation of the school, etc.) [Permette alla scolaresca di esprimere liberamente opinioni e necessità (rispetto al proprio processo educativo, alle norme e al funzionamento dell’Istituto)]. | ||||

| 16. Promotes action-research projects in the school in order to guide improvement processes [Stabilisce progetti di ricerca-azione nell’istituto al fine di orientare processi di miglioramento] | ||||

| 17. Proposes activities and designs strategies (seminars, courses, conferences, etc.) to address teachers’ perceptions, stereotypes, etc. in order to guarantee respect for students’ diversity and equal opportunities [Propone attività e progetta strategie (seminari, corsi, conferenze, etc.) per trattare le percezioni, gli stereotipi del corpo docente al fine di garantire il rispetto della diversità della scolaresca e l’uguaglianza di opportunità] | ||||

| 18. Encourages teachers to participate in educational activities organized by the local community [Favorisce la partecipazione del corpo docente alle attività educative organizzate dalla comunità locale] | ||||

| 19. Promotes a shared vision among the teachers on the organization, goals and activities to share a common project with them [Favorisce tra il corpo docente una visione condivisa sull’organizzazione, le mete e le attività per renderlo partecipe di un progetto commune] | ||||

| 20. Establishes protocols to address conflicts through dialogue, mediation and negotiation among the parties involved [Promuove protocolli per affrontare i conflitti attraverso il dialogo, la mediazione e la negoziazione tra le parti implicate] | ||||

| 21. Establishes sanctions for the use of symbols and actions that promote exclusion [Stabilisce sanzioni per l’uso di simboli e azioni che promuovono l’esclusione] | ||||

| 22. Develops educational programmes to prevent discriminatory attitudes among students [Sviluppa programmi educativi per prevenire atteggiamenti discriminatori tra la scolaresca] | ||||

| 23. Generates opportunities for all members of the educational community to participate effectively in decisions [Crea opportunità affinché tutti i membri della comunità educativa partecipino in modo effettivo alle decisioni] | ||||

| 24. The management team shall promote reception activities for all students and for newly-incorporated teachers [Lo staff di dirigenza promuove le attività di accoglienza per tutti gli studenti e per gli insegnanti nuovi arrivati] | ||||

| 25. Fosters activities that promote mutual knowledge among the school’s students [Sostiene attività che potenziano la conoscenza reciproca tra la scolaresca dell’istituto] | ||||

| 26. Promotes collaboration among teachers to improve teaching by facilitating time and space to them [Incoraggia la collaborazione tra il corpo docente, per migliorare l’insegnamento facilitando tempi e spazi] | ||||

| 27. Be interested in knowing teachers’ position on student diversity [Si preoccupa di conoscere la posizione del corpo docente in relazione alla diversità della scolaresca] | ||||

| 28. Promotes spaces for reflection among the teaching staff on the conditions of equality offered by the school [Favorisce spazi di riflessione tra i membri del corpo docente sulle condizioni di uguaglianza che offre l’istituto] | ||||

| 29. Sensitizes teachers about the need to communicate situations of discrimination or exclusion that may occur in the school [Sensibilizza il corpo docente sulla necessità di comunicare situazioni di discriminazione o esclusione che possano verificarsi nell’istituto] | ||||

| 30. Organizes actions that enable the staff to reflect on their practice and and evalute the possible influence of their teaching on student failure [Organizza azioni al fine di promuovere la riflessione degli insegnanti sulla loro pratica educativa e di valutare il possibile impatto del loro insegnamento sull’insuccesso scolastico] | ||||

| 31. Sensitizes teachers to have high expectations of all students [Sensibilizza il corpo docente affinché abbia alte aspettative verso tutta la scolaresca] | ||||

| 32. Be concerned that the planning of teaching is done in a coordinated way among the teaching staff [Si preoccupa che la pianificazione dell’insegnamento sia fatta in modo coordinato tra il personale docente] | ||||

| 33. Promotes a flexible and revisable curriculum to respond to the needs of students in accordance with the principles of the Curriculum for All (academic, personal, social, …) [Promuove un curriculo flessibile e controllabile per dare risposta alle necessità della scolaresca concorde coi principi del Curriculum per tutti (accademico, personale, sociale)] | ||||

| 34. Promote an evaluation of curricular materials to ensure that they do not contribute to the exclusion of students [Si interessa di garantire l’uguaglianza di opportunità mobilitando risorse (materiali ed umane) che favoriscono l’inclusione] | ||||

| 35. Be interested in ensuring that all students are represented in the contents that are being taught [Si interessa perché tutta la scolaresca si veda rappresentata nei contenuti che si insegnano] | ||||

| 36. Promotes the continuous development of activities that enhance solidarity, empathy and assertiveness among students in the classroom [Promuove il continuo sviluppo di attività che favoriscono la solidarietà, l’empatia e l’assertività tra gli studenti in classe] | ||||

| 37. Takes care that teachers set different criteria and procedures for evaluating students [Si preoccupa che il corpo docente fissi criteri e procedimenti diversi per valutare la scolaresca] | ||||

| 38. Promotes the evaluation of teaching practices to determine the degree to which they foster the inclusion of students [Promuove la valutazione delle pratiche didattiche per determinare il grado in cui esse favoriscono l’inclusione degli student] | ||||

| 39. Ensures that evaluation has been carried out in a coordinated and interdisciplinary manner [Si adopera affinchè la valutazione si realizzi in maniera coordinata ed interdisciplinare] | ||||

| 40. Encourages students’ participation in the evaluation processes [Incoraggia la partecipazione degli studenti ai processi di valutazione] | ||||

| Dimension I. Openness to the community [dimensione i. apertura verso la comunita’] The management team… [lo staff di dirigenza…] | Scale [Scala] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. It promotes initiatives that foster the participation of community members in the educational process and in the life of the school [Spinge iniziative che favoriscono la partecipazione dei membri della comunità al processo formativo e alla vita dell’ istituto] | ||||

| 2. Establishes a plan of actions, developed in collaboration with other members of the community to promote the school/community relations and respond to student diversity [Stabilisce un piano di azioni, elaborato in sinergia con altri membri della comunità, per promuovere le relazioni scuola/comunità locale e rispondere alla diversità della scolaresca] | ||||

| 3. Participates in the actions undertaken by other education institutions/organizations of the community (sports activities, days against racism, etc.) [Participa alle azioni intraprese da altre istituzioni /organizzazioni della comunità di carattere educativo (attività sportive, giornata contro razzismo, etc.)] | ||||

| 4. Offer the school’s facilities and resources for the development of activities (cultural, educational, etc.) of interest to the community [Offre le strutture e le risorse dell’istituto per lo sviluppo di attività (culturali, educative, …) di interesse per la comunità] | ||||

| 5. Inform the family of the proposed curriculum to orient the educational action of the school through various channels of communication [Informa la famiglia della proposta curriculare che guida l’azione educativa dell’istituto attraverso diversi canali di comunicazione] | ||||

| 6. Promote actions to sensitize families on the importance and benefits of inclusion [Promuovere azioni di sensibilizzazione delle famiglie sull’importanza e i benefici dell’inclusione] | ||||

| 7. Promote actions that facilitate communication and participation of all families in educational activities undertaken inside and outside the school setting [Promuove azioni che facilitano la comunicazione e la partecipazione di tutte le famiglie alle attività educative intraprese all’interno e all’esterno dell’ambiente scolastico] | ||||

| 8. To listen and take into account the demands and needs of all families [Ascolta tiene conto delle esigenze e dei bisogni di tutte le famiglie] | ||||

| 9. Promote activities that boost mutual knowledge, e interchange and coexistence among families and other members of the school [Promuove attività che favoriscono la conoscenza reciproca, lo scambio e la convivenza tra le famiglie e gli altri membri dell’istituzione educative] | ||||

| 10. Establish measures to prevent negative influences that the family situation could have on the success of students (campaigns of help, support for learning schools for parents, etc.) [Prevede misure per contrastare l’influenza negativa che la situazione familiare potrebbe avere sul successo dei suoi studenti (campagne di aiuto, sostegno all’apprendimento, incrontri con i genitori, etc.)] | ||||

| 11. Promotes student participation in the governing bodies of the school [Promuove la partecipazione degli studenti negli organi collegiali della scuola] | ||||

| Dimension II. The school as an inclusive space [dimensione ii. la scuola come spazio inclusivo] The management team… [lo staff di dirigenza…] | Scale [Scala] | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 12. To concern itself that the services offered by the school respect the different needs of the students (religious sensibilities, food intolerance, health problems, etc.) [Si preoccupa che i servizi offerti dall’istituto rispettino le diverse esigenze degli studenti (sensibilità religiose, intolleranze alimentari, problemi di salute, etc.)] | ||||

| 13. Be interested in ensuring equality of opportunities using material and human resources with the aim of fostering inclusion [Si interessa di garantire le pari opportunità mobilitando risorse (materiali e umane) al fine di favorire l’inclusione]. | ||||

| 14. Concern itself that the school has the material and human resources (specifically professional) to promote improvement [Si occupa di fornire all’istituto risorse materiali e umane (personale specializzato) per promuovere processi di miglioramento] | ||||

| 15. Work to give an institutional atmosphere in which the student is recognized, helped and valued [Si impegna affinche’esista un clima istituzionale in cui tutti gli studenti siano riconosciuti, seguiti e valorizzati] | ||||

| 16. Promote a shared vision among the teachers on the organization, goals and activities to share a common project with them [Favorisce tra il corpo docente una visione condivisa sull’organizzazione, le mete e le attività per renderlo partecipe di un progetto commune] | ||||

| 17. Give clear information about the admission and enrollment processes to ensure that they reach all students equally [Fornisce una informazione trasparente sul processo di ammissione e di registrazione per garantire che raggiunga tutti gli stakeholder in egual misura] | ||||

| 18. Take measures to prevent and avoid truancy [Adotta misure per prevenire ed evitare l’assenteismo] | ||||

| 19. Establish sanctions for the use of symbols and actions that promote exclusion [Stabilisce sanzioni per l’uso di simboli e azioni che promuovono l’esclusione] | ||||

| 20. Develop educational programmes to prevent discriminatory attitudes among students [Sviluppa programmi educativi per prevenire atteggiamenti discriminatori tra la scolaresca] | ||||

| 21. Share authority and responsibility with the teaching staff [Condivide autorità e responsabilità con i docent] | ||||

| 22. Generate opportunities for all members of the educational community to participate effectively in decisions [Crea opportunità affinché tutti i membri della comunità educativa partecipino in modo effettivo alle decisioni] | ||||

| 23. Enable the different members of the educational community to participate in the evaluation of management tasks [Permette ai diversi membri della comunità educativa di partecipare alla valutazione dei compiti di gestione] | ||||

| 24. Promote actions to welcome all students [Promuove azioni di benvenuto per tutti gli student] | ||||

| 25. Establish mechanisms to promote the participation of students in the regulation of conflicts that arise in the school environment [Promuove meccanismi per stimolare la partecipazione della scolaresca nella regolazione di conflitti che sorgono nell’ambiente educativo] | ||||

| 26. Encourage the students to express freely their opinions and needs (regarding their educational process, standards and operation of the school, etc.) [Permette alla scolaresca di esprimere liberamente opinioni e necessità (rispetto al proprio processo educativo, alle norme e al funzionamento dell’istituto)]. | ||||

References

- Smith, M.J. Sustainable Development Goals: Genuine global change requires genuine measures of efficacy. J. Maps. 2020, 16, i–iii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. We Can End Poverty: MILLENNIUM Development Goals and Beyond 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Alonso-García, S.; Aznar-Díaz, I.; Cáceres-Reche, M.P.; Trujillo-Torres, J.M.; Romero-Rodríguez, J.M. Systematic Review of Good Teaching Practices with ICT in Spanish Higher Education. Trends and Challenges for Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hallinger, P.; Heck, R.H. Leadership for learning: Does collaborative leadership make a difference? Educ. Manag. Adm. Lead. 2010, 38, 654–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hallinger, P.; Huber, S. School leadership that makes a difference: International perspectives. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 2012, 23, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, K.S.; Leithwood, K.A.; Wahlstrom, K.L.; Anderson, S.E. Learning from Leadership: Investigating the Links to Improved Student Learning; Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente-Anuncibay, R.; González-Bernal, J.; de Diego-Vallejo, R.; Caggiano, V. Liderazgo educativo en centros de secundaria. Relación con la percepción y la satisfacción laboral del profesorado. CADMO 2017, 2, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agasisti, T.; Bowers, A.J.; Soncin, M. School principals’ leadership types and students’ achievement in the Italian context: Empirical results from a three-step Latent Class Analysis. Educ. Manag. Adm. Lead. 2019, 47, 860–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, A.J. Examining a Congruency-Typology Model of Leadership for Learning using Two-Level Latent Class Analysis with TALIS 2018; OECD iLibrary: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Principal Instructional Leadership: From Prescription to Theory to Practice. In The Wiley Handbook of Teaching and Learning; Hall, G.E., Quinn, L.F., Gollnick, D.M., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 505–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. J. Educ. Adm. 2011, 49, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, J.; Bowers, A.J. Toward an evolving conceptualization of instructional leadership as leadership for learning: Meta-narrative review of 109 quantitative studies across 25 years. J. Educ. Adm. 2018, 56, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q.; Sammons, P. The Impact of Leadership on Student Outcomes: How Successful School Leaders Use Transformational and Instructional Strategies to Make a Difference. Educ. Adm. Quart. 2016, 52, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, M.J.; Romero, A.; Navarro, R. Liderazgo inclusivo en los centros educativos. In Actas del I Congreso Internacional Educación Inclusiva en la Universidad; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- León, M.J.; Moreno, R. El liderazgo inclusivo en zonas desfavorecidas vs. favorecidas. In Avances en Liderazgo y Mejora de la Educación: Actas del I Congreso Internacional de Liderazgo y Mejora de la Educación; Murillo, F.J., Ed.; UAM_Biblioteca: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dettori, F. La integración de alumnos con necesidades educativas especiales en Europa: El caso de España e Italia. Rev. Educ. Incl. 2011, 4, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bezzina, C.; Paletta, A.; Alimehmeti, G. What are school leaders in Italy doing? An observational study. Educ. Manag. Adm. Lead. 2018, 46, 841–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, A.; Bezzina, C. Governance and leadership in public schools: Opportunities and challenges facing school leaders in Italy. Lead. Pol. Sch. 2016, 15, 524–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, A.; Basyte, E.; Alimehmet, G. How Principals Use a New Accountability System to Promote Change in Teacher Practices: Evidence from Italy. Educ. Adm. Quart. 2020, 56, 123–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Murphy, J.F. Assessing and developing principal instructional leadership. Educ. Lead. 1987, 45, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, A.C.; Polikoff, M.S.; Goldring, E.B.; Murphy, J.F.; Elliott, S.N.; May, H. Developing a Psychometrically Sound Assessment of School Leadership: The VAL-ED as a Case Study. Educ. Adm. Quart. 2010, 46, 135–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCED. Mejorar el Liderazgo Escolar: Política y Prácticas; OECD Publishing: Prais, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- León, M.J.; López, M.C.; Romero, A.; Hinojosa, E.; Moreno, R. Liderando la educación inclusiva en centros de educación primaria y secundaria. In Libro de Simposios del XIV Congreso Interuniversitario de Organización de Instituciones Educativas (CIOIE); Bernal, J.L., Ed.; Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, España, 2016; pp. 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Beh. Res. Meth. Instr. Comp. 2006, 38, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bentler, P.M.; Yuan, K.H. Structural equation modeling with small samples: Test statistics. Mult. Beh. Res. 1999, 34, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunch, N.J. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling Using IBM SPSS Statistics and Amos, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Arribas, M.C. Diseño y validación de cuestionarios. Matronas Profesión 2004, 5, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Pérez, J.; Cuervo-Martínez, A. Validez de contenido y juicio de expertos: Una aproximación a su utilización. Avances en Medición 2008, 6, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schmider, E.; Ziegler, M.; Danay, E.; Beyer, L.; Bühner, M. Is it really robust? Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Methodology 2010, 6, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step-by-Step: A Simple Guide and Reference (14.0 update), 7th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hérnandez-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: Una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anal. Psichol. 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, M.J. La dirección de las instituciones educativas y la atención a la diversidad. In Viaje al Centro de la Dirección de Instituciones Educativas; De Vicente Rodríguez, P., Ed.; Ediciones Mensajero: Bilbao, España, 2001; pp. 399–417. [Google Scholar]

- León, M.J. El liderazgo para y en la escuela inclusiva. Educ. Sigl. XXI 2012, 30, 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman, M.E.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Dimensionality Assessment of Ordered Polytomous Items with Parallel Analysis. Psych. Meth. 2011, 16, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, T.L. Essential Traits of Mental Life, Harvard Studies in Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Carretero-Dios, H.; Pérez, C. Standards for the development and the review of instrumental studies: Considerations about test selection in psychological research. Int. J. Clin. Heal. Psychol. 2007, 7, 863–882. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. In Methodological Issues & Strategies in Clinical Research, 3rd ed.; Kazdin, A.E., Ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 207–231. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosua, P.; Zumbo, B.D. Coeficientes de fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada. Psicothema 2008, 20, 896–901. [Google Scholar]

- Cea, D.; Ancona, M.A. Metodología Cuantitativa: Estrategias y Técnicas de Investigación Social; Síntesis: Madrid, Espala, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, D.J. El Proceso de Investigación en Educación; Eunsa: Pamplona, España, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, T.J.; Baguley, T.; Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Brith. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Bearden, W.O.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; SAGE: Newcastle, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Draft Joint Employment Report. Brussels, Belgium. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017DC0674&from=EN (accessed on 17 November 2018).

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V01 | 2.93 | 0.74 | 0.547 | −0.336 | −0.111 |

| V02 | 2.87 | 0.75 | 0.559 | −0.270 | −0.217 |

| V03 | 2.47 | 0.90 | 0.809 | −0.044 | −0.771 |

| V04 | 2.78 | 0.84 | 0.701 | −0.242 | −0.537 |

| V05 | 2.58 | 0.94 | 0.885 | −0.110 | −0.872 |

| V06 | 2.91 | 0.78 | 0.613 | −0.356 | −0.271 |

| V07 | 3.02 | 0.80 | 0.634 | −0.525 | −0.142 |

| V08 | 2.94 | 0.79 | 0.620 | −0.263 | −0.538 |

| V09 | 2.73 | 0.86 | 0.738 | −0.124 | −0.693 |

| V10 | 2.82 | 0.82 | 0.674 | −0.360 | −0.330 |

| V11 | 2.89 | 0.80 | 0.641 | −0.328 | −0.384 |

| V12 | 2.70 | 0.89 | 0.784 | −0.292 | −0.600 |

| V13 | 2.83 | 0.87 | 0.756 | −0.413 | −0.452 |

| V14 | 2.94 | 0.82 | 0.668 | −0.482 | −0.207 |

| V15 | 3.04 | 0.78 | 0.610 | −0.498 | −0.162 |

| V16 | 2.92 | 0.81 | 0.650 | −0.334 | −0.450 |

| V17 | 2.87 | 0.87 | 0.759 | −0.405 | −0.513 |

| V18 | 2.96 | 0.84 | 0.705 | −0.450 | −0.426 |

| V19 | 2.94 | 0.84 | 0.710 | −0.371 | −0.569 |

| V20 | 2.85 | 0.85 | 0.715 | −0.321 | −0.522 |

| V21 | 2.96 | 0.84 | 0.705 | −0.472 | −0.364 |

| V22 | 3.01 | 0.82 | 0.669 | −0.589 | −0.083 |

| V23 | 2.86 | 0.84 | 0.705 | −0.328 | −0.506 |

| V24 | 3.03 | 0.86 | 0.743 | −0.566 | −0.393 |

| V25 | 3.00 | 0.76 | 0.580 | −0.418 | −0.172 |

| V26 | 3.00 | 0.82 | 0.662 | −0.496 | −0.266 |

| V27 | 2.95 | 0.85 | 0.721 | −0.500 | −0.331 |

| V28 | 2.79 | 0.87 | 0.759 | −0.267 | −0.634 |

| V29 | 3.05 | 0.81 | 0.646 | −0.522 | −0.256 |

| V30 | 2.87 | 0.88 | 0.772 | −0.387 | −0.575 |

| V31 | 2.99 | 0.86 | 0.730 | −0.580 | −0.258 |

| V32 | 3.10 | 0.83 | 0.680 | −0.619 | −0.234 |

| V33 | 3.01 | 0.82 | 0.672 | −0.541 | −0.208 |

| V34 | 3.06 | 0.82 | 0.669 | −0.521 | −0.365 |

| V35 | 2.99 | 0.82 | 0.665 | −0.435 | −0.401 |

| V36 | 3.03 | 0.73 | 0.617 | −0.478 | −0.225 |

| V37 | 3.12 | 0.80 | 0.633 | −0.754 | 0.275 |

| V38 | 2.94 | 0.85 | 0.720 | −0.354 | −0.622 |

| V39 | 3.16 | 0.78 | 0.601 | −0.646 | −0.072 |

| V40 | 3.03 | 0.81 | 0.648 | −0.444 | −0.416 |

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V01 | 2.44 | 0.89 | 0.783 | 0.052 | −0.720 |

| V02 | 2.40 | 0.88 | 0.774 | 0.004 | −0.739 |

| V03 | 2.45 | 0.98 | 0.951 | 0.047 | −0.991 |

| V04 | 2.51 | 0.96 | 0.926 | −0.054 | −0.952 |

| V05 | 2.67 | 0.94 | 0.884 | −0.227 | −0.832 |

| V06 | 2.43 | 0.96 | 0.921 | 0.014 | −0.960 |

| V07 | 2.38 | 0.91 | 0.825 | 0.095 | −0.796 |

| V08 | 2.49 | 0.94 | 0.889 | −0.006 | −0.899 |

| V09 | 2.24 | 0.95 | 0.911 | 0.238 | −0.922 |

| V10 | 2.53 | 0.93 | 0.856 | −0.001 | −0.848 |

| V11 | 2.60 | 0.95 | 0.900 | −0.162 | −0.882 |

| V12 | 2.58 | 0.89 | 0.787 | −0.135 | −0.704 |

| V13 | 2.47 | 0.91 | 0.830 | −0.012 | −0.807 |

| V14 | 2.58 | 0.92 | 0.848 | −0.066 | −0.833 |

| V15 | 2.58 | 0.86 | 0.740 | −0.068 | −0.644 |

| V16 | 2.57 | 0.89 | 0.790 | −0.076 | −0.727 |

| V17 | 2.66 | 0.92 | 0.851 | −0.177 | −0.807 |

| V18 | 2.36 | 0.91 | 0.828 | 0.142 | −0.784 |

| V19 | 2.59 | 0.90 | 0.804 | −0.144 | −0.729 |

| V20 | 2.75 | 0.87 | 0.762 | −0.226 | −0.657 |

| V21 | 2.53 | 0.90 | 0.800 | −0.068 | −0.746 |

| V22 | 2.39 | 0.87 | 0.757 | −0.005 | −0.720 |

| V23 | 2.59 | 0.93 | 0.853 | −0.133 | −0.818 |

| V24 | 2.29 | 1.01 | 1.017 | 0.136 | −0.999 |

| V25 | 2.51 | 0.88 | 0.779 | −0.037 | −0.714 |

| V26 | 2.55 | 0.97 | 0.802 | −0.062 | −0.751 |

| Variables | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| V01 | 0.727 | |

| V02 | 0.861 | |

| V03 | 0.979 | |

| V04 | 0.963 | |

| V05 | 0.998 | |

| V06 | 0.751 | |

| V07 | 0.599 | |

| V08 | 0.748 | |

| V09 | 0.779 | |

| V10 | 0.635 | |

| V11 | 0.458 | |

| V12 | 0.579 | |

| V13 | 0.589 | |

| V14 | 0.800 | |

| V15 | 1.016 | |

| V16 | 0.691 | |

| V17 | 0.515 | |

| V18 | 0.758 | |

| V19 | 0.687 | |

| V20 | 0.587 | |

| V21 | 0.693 | |

| V22 | 0.811 | |

| V23 | 0.760 | |

| V24 | 0.938 | |

| V25 | 0.676 | |

| V26 | 0.868 | |

| V27 | 0.889 | |

| V28 | 0.748 | |

| V29 | 0.924 | |

| V30 | 0.718 | |

| V31 | 0.911 | |

| V32 | 1.038 | |

| V33 | 0.854 | |

| V34 | 0.825 | |

| V35 | 1.035 | |

| V36 | 0.981 | |

| V37 | 0.851 | |

| V38 | 0.492 | |

| V39 | 0.916 | |

| V40 | 0.799 |

| Variables | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| V01 | 0.793 | |

| V02 | 0.958 | |

| V03 | 0.885 | |

| V04 | 0.707 | |

| V05 | 0.474 | |

| V06 | 0.801 | |

| V07 | 0.752 | |

| V08 | 0.409 | |

| V09 | 0.718 | |

| V10 | 0.559 | |

| V11 | 0.562 | |

| V12 | 0.449 | |

| V13 | 0.517 | |

| V14 | 0.667 | |

| V15 | 0.649 | |

| V16 | 0.839 | |

| V17 | 0.840 | |

| V18 | 0.673 | |

| V19 | 0.928 | |

| V20 | 1.062 | |

| V21 | 0.891 | |

| V22 | 0.642 | |

| V23 | 0.729 | |

| V24 | 0.954 | |

| V25 | 0.756 | |

| V26 | 0.716 |

| Factors | Men | Women | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| The school as an inclusive community | 3.28 | 0.78 | 3.01 | 0.70 | 2.81 | 0.094 |

| Management of teaching-learning processes and teachers’ professional development | 3.13 | 0.65 | 2.96 | 0.69 | 1.14 | 0.271 |

| Factors | Men | Women | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Openness to the community | 2.54 | 0.74 | 2.41 | 0.71 | 2.11 | 0.035 * |

| The school as an inclusive space | 2.46 | 0.69 | 2.37 | 0.65 | 1.69 | 0.091 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crisol Moya, E.; Molonia, T.; Caurcel Cara, M.J. Inclusive Leadership and Education Quality: Adaptation and Validation of the Questionnaire “Inclusive Leadership in Schools” (LEI-Q) to the Italian Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135375

Crisol Moya E, Molonia T, Caurcel Cara MJ. Inclusive Leadership and Education Quality: Adaptation and Validation of the Questionnaire “Inclusive Leadership in Schools” (LEI-Q) to the Italian Context. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135375

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrisol Moya, Emilio, Tiziana Molonia, and María Jesús Caurcel Cara. 2020. "Inclusive Leadership and Education Quality: Adaptation and Validation of the Questionnaire “Inclusive Leadership in Schools” (LEI-Q) to the Italian Context" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135375

APA StyleCrisol Moya, E., Molonia, T., & Caurcel Cara, M. J. (2020). Inclusive Leadership and Education Quality: Adaptation and Validation of the Questionnaire “Inclusive Leadership in Schools” (LEI-Q) to the Italian Context. Sustainability, 12(13), 5375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135375