Abstract

The recent outbreak of a new Coronavirus has developed into a global pandemic with about 10.5 million reported cases and over 500,000 deaths worldwide. Our prospective paper reports an updated analysis of the impact that this pandemic had on the Italian agri-food sector during the national lockdown and discusses why and how this unprecedented economic crisis could be a turning point to deal with the overall sustainability of food and agricultural systems in the frame of the forthcoming European Green Deal. Its introductory part includes a wide-ranging examination of the first quarter of pandemic emergency, with a specific focus on the primary production, to be understood as agriculture (i.e., crops and livestock, and their food products), fisheries, and forestry. The effect on the typical food and wine exports, and the local environment tourism segments is also taken into account in this analysis, because of their old and deep roots into the cultural and historical heritage of the country. The subsequent part of the paper is centered on strategic lines and research networks for an efficient socio-economic and territorial restart, and a faster transition to sustainability in the frame of a circular bio-economy. Particular emphasis is given to the urgent need of investments in research and development concerning agriculture, in terms of not only a fruitful penetration of the agro-tech for a next-generation agri-food era, but also a deeper attention to the natural and environmental resources, including forestry. As for the rest of Europe, Italy demands actions to expand knowledge and strengthen research applied to technology transfer for innovation activities aimed at providing solutions for a climate neutral and resilient society, in reference to primary production to ensure food security and nutrition quality. Our expectation is that science and culture return to play a central role in national society, as their main actors are capable of making a pivotal contribution to renew and restart the whole primary sector and agri-food industry, addressing also social and environmental issues, and so accelerating the transition to sustainability.

Keywords:

COVID-19; agriculture; food industry; applied research; technology transfer; sustainability; Italy 1. Introduction and Background Information

The purpose of this document is to sort and analyse data and rework information regarding the impact of the new Coronavirus, which is known to cause a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in humans (SARS-CoV-2 better known as COVID-19), on the territorial production systems and agri-foodstuff sectors during the first three months of the pandemic crisis in Italy, and to develop some reflections on the scenario that could arise in the immediate post-emergency period, with some fruitful ideas and strategic guidelines for the country’s economic and social recovery.

The Johns Hopkins University, which collects data on confirmed cases and deaths from Coronavirus worldwide, reports that as of 1st July 2020 there are around 10.5 million cases and more than 500,000 deaths worldwide (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). Italy ranks sixth in the world for number of cases and second in Europe for number of deaths, after the United Kingdom. Comparing the increases in cases and deaths worldwide in the last weeks would confirm the hypothesis that, while the virus continues to spread at even higher speeds than before, its fatality rate may be decreasing. As a matter of fact, recurrent mutations currently in circulation for the COVID-19 appear to be either fully neutral or weakly deleterious, as demonstrated recently by van Dorp et al. [1]. Very recently, He et al. [2] found also that the gut microbiota enhances antiviral immunity by increasing the number and function of immune cells, decreasing immunopathology, and stimulating interferon activity. In turn, respiratory viruses are known to influence microbial composition in the lung and intestine [2]. Therefore, individual diets can affect the microbiota and the analysis of changes in the microbiota during SARS-CoV-2 infection may help predict patient outcomes and allow the development of specific therapies targeting the microbiota.

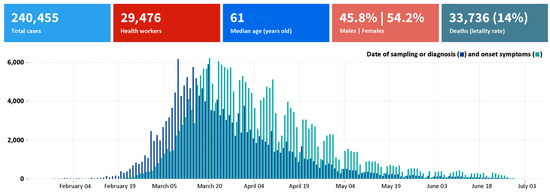

The available statistics also show an apparent anomaly for Italy, since according to available official estimates the fatality rate appears to be much higher (13.8%) than the world average (6.6%). Today in our country there are a total of about 240 thousand confirmed cases, almost 34,000 deaths (14%) with a median age of 61 years (45.8% male and 54.2% female), a test positivity rate is <1%, and it is estimated that at the end of July or beginning of August there will be zero new cases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Epidemic curve of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) total cases reported in Italy plot by date of sampling or diagnosis (■) and by date of onset symptoms (■). Data verified on 1st July 2020 (source: Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS (https://www.iss.it/en/home). The main COVID-19 statistics of Italy and geographic distribution of the number of cases sorted by provinces could also be retrieved at the following link: https://r-ubesp.dctv.unipd.it/shiny/covid19italy/source: DCTV, School of Medicine, University of Padua, Italy.

The reopening of all activities in the territories is imminent being programmed on 6 July 2020 while the restoration of mobility between regions is already ongoing since 18 May 2020. In a couple of months, we may be completely on the other side of the COVID-19 emergency. The time has therefore come to accurately estimate the impact of the lockdown on the production chains of the agri-foodstuffs sector at national level, in order to develop successful ideas and efficient strategies for the post COVID-19 recovery of the entire primary sector of the economy (i.e., any industry involved in the extraction and/or production of raw materials, such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, and mining [3]). This is a crucial phase, since the feeling is that with the right decisions and targeted actions, the current crisis could represent an epochal turning point for one of the country’s most strategic sectors, that of land resources and food productions. This also has close ties with the food and wine tourism sector, with its strong territorial roots, a market that has doubled its figures in Italy in the last year, with an economic impact that exceeded 12 billion euros (15% of total tourism) of expenditure by foreign tourists alone (source ISMEA: Institute of Services for the Agricultural Food Market, http://www.ismea.it/). All the structures of this system, including businesses and political and economic institutions, but also scientific and cultural ones, both public and private, will have to communicate with each other and collaborate in an efficient and coordinated way. We are confident that both communication and collaboration are key factors for a successful Third Mission of universities, which seeks to generate knowledge outside academic environments to the benefit of the social and economic development, in order to support national activities and improve international competitiveness, from production to trade.

By way of a general premise, a first observation is necessary: the succession of events following the spread of Coronavirus was undoubtedly rapid and sudden, causing unforeseeable situations for the Italian population, the extent of which would have been hard to imagine even just a few weeks before the declaration of the state of emergency owing to the pandemic. In the space of a few days, initiatives that were initially deemed to be exaggerated and that were welcomed on the whole with confusion appeared insufficient, triggering a rush for further, contingent, and more stringent operating protocols which, if on the one hand highlighted an unexpected reaction/action capacity of many components of society (here we suggest a direct connection with the psychology of emergency), on the other hand did not allow time for thinking about the vastness of the problem at the health level, nor perhaps for understanding the dramatic nature of the social and economic consequences. It could also be said that the experience of the First Pandemic of the New Millennium constitutes an unprecedented moral teaching for all generations following those who lived through the Second World War.

In the general uncertainty resulting from a national lockdown decided upon and applied almost immediately, the population promptly reconfigured their daily needs, prioritising their health and that of their relatives, along with the supply of foodstuffs (and drinks) to deal with home/family quarantine, according to ISMEA periodical surveys. In fact, with regard to the latter aspect, and as highlighted by the Minister of Agriculture, “food is an essential good and we must be grateful to the entire agri-foodstuffs chain for what it is doing and will continue to do.” However, as in other sectors of the economy (i.e., industries that produce finished and usable products or services), in this phase of emergency the agri-foodstuffs sector has thousands of entrepreneurs in difficulty who are of fundamental importance because “they produce, they grow plants and raise animals, they fish and they transform food” (statement given by the current Italian Minister of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies). Undoubtedly the primary sector, particularly agriculture and its associated food industry, is a sector of great strategic importance for Italy.

The Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies recently published a quarterly report (period 1st February–30th April 2020) concerning the formal checks carried out in the agri-foodstuffs chain: the ICQRF (The Italian Central Inspectorate of Quality Protection and Fraud Repression in the agri-food production sector) overall activity report is available at the following link https://www.politicheagricole.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/15410. This document shows, with precision, the enormous effort that was made by the Italian agri-food supply chain during the first three months of the COVID-19 emergency in order to guarantee Italians—under the supervision of the MiPAAF—quality produce during the lockdown.

Over a third of the checks (about 35%) were carried out in the northern area of the country: despite the dramatic epidemic crisis, over 17% of the ICQRF checks took place in the Lombardy and Veneto regions, to guarantee that quality of production was maintained by the regions that guarantee the two largest “geographical indications” in the world in quantitative terms: Grana Padano, with over 5.2 million cheeses, and Prosecco Wine, with over 600 million bottles. The ICQRF laboratories analysed 2705 samples for 69,779 analytical determinations, with irregularity rates, both for inspection activities and for analytical activities, in line with the indices recorded before the state of emergency (for details, see pages 3–5 of the ICQRF report).

2. General Analysis of the Impact of COVID-19 on the Primary Sector, Including Agricultural Activity, Food Industry, and Forestry

In regards to the immediate impact of COVID-19 on the agri-food sector, the first ISMEA report (30 March 2020) is remarkable and paves the way for understanding the central role of agriculture and food industry on the supply of food products and their demand in the first weeks of Coronavirus spread during the National lockdown (available at the following link http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/10990).

Since the beginning of the pandemic (in Italy the virus was first reported on 31 January 2020, then a cluster of cases was later detected in Lombardy on 21 February 2020 [4]), the agri-foodstuffs sector has been firmly in the foreground, in importance second only to the medical-health sector which, for obvious reasons, is constantly at the centre of attention, constituting the main focus of all media. On the local consumer front, there was an immediate instinctive response in the hoarding of basic necessities and food, and on the political front, the awareness that the proper functioning of the supply chain and the ability to ensure the supply of food represented an important indicator both economically and socially.

According to the ISMEA experts, on the basis of the data available and collected in this report, the agri-foodstuffs sector based on raw materials of vegetable and animal origin—with some obvious exceptions (such as nursery gardening and fishing)—has been and continues to be one of the least affected by the economic storm of these first months of pandemic emergency, largely confirming its stability and anticyclical property (i.e., sales not conforming to or following a cycle, which rise when the economy fades).

At a territorial level, after an initial phase of adjustment, it is true that there have been no particular problems in the procurement of agri-food products. However, it is equally true that the uncontrolled and uncontrollable dynamic of events, both those that have taken place and those that are still unfolding, give no certainties about the future of this sector, in the short to medium term, at a national level. Indeed, the ISMEA report on COVID-19 emergency highlights that just a few weeks after the start of the crisis, the overall scenario appeared to have changed substantially through, for example, the gradual closure of the Ho.Re.Ca. channel (private and public food service industry, the channel represented by those who, by profession, supply food and drinks—the term is the syllabic abbreviation of the words Hotel/Restaurant/Café), not only nationally but also internationally. This entailed the consequent blockage of the main channel in which “Made in Italy” agri-food products have a medium-high positioning, and which absorbs significant percentages of the total export flows.

The National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) communicated that on average in the first quarter of the year, the seasonally adjusted level of production decreased by more than 8% compared to the three months preceding the start of the pandemic. In the respective note, we read that “demand conditions and measures to contain the COVID-19 epidemic have led to a collapse in Italian industrial production.” In trend terms, the calendar-adjusted index shows the largest decrease in the thirty-year historical records available, exceeding the values recorded during the crisis of 2008–2009. All the main sectors of economic activity recorded downturns, in many cases of unprecedented intensity: in the manufacture of transport vehicles and in the textile, clothing, leather, and accessories industries, the fall far exceeds 50%; the decrease is instead modest in the food and beverage industries (−6%) which, considering the average of the last three months, maintains a positive trend (Source: ISTAT, https://www.istat.it/en/).

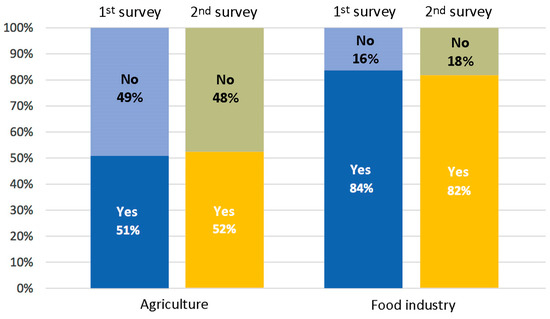

At a national level, two consecutive surveys conducted on agri-food businesses suggest that, after three months of emergency, the food industry is suffering more greatly from the lockdown than the farms themselves: 82%–84% of the industrialists interviewed said they were in difficulty, compared with 51%–52% of the farmers questioned (Figure 2). In fact, most agricultural activities are carried out outdoors, so compliance with safety standards is easier than for an indoor plant. In particular, still with regard to agriculture, the impact of the crisis on cereal and olive oil companies is even more limited, as they are currently less active than at other times of the year. Greater difficulties were encountered in the livestock sector, which together with wine, is among those that most report a drop in sales. At the industrial level, the fruit and vegetable processing sector, along with the pasta, rice and milling sectors are among the least pessimistic, having benefited from the rush to purchase non-perishable products and ingredients in the first weeks of the lockdown. On the other hand, companies in the confectionery and baking industries were particularly pessimistic, evidently affected by the limitations on travel and therefore socialising. More generally, in this phase it is possible to take stock of some elements that characterise the market dynamics and that transversely affect all the agri-foodstuff chains, albeit with different intensity.

Figure 2.

Proportions of farmers and entrepreneurs who have experienced difficulties in business management in the primary sector (mainly agriculture and fishery) and food industry during the national lockdown (the two distinct fact-finding surveys were carried out during March and April 2020, source: ISMEA, Institute of Services for the Agricultural Food Market, Rome, Italy: for additional information on food production/transformation and market trends see first COVID-19 emergency report (published on 30 March 2020) available at the following link http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/10990 and second COVID-19 emergency report (published on 30 April 2020) available at the following link http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/11016).

The most significant phenomenon was and certainly continues to be represented by the cancellation of the private and public restaurant and catering channel because of the national lockdown (on 9 March 2020, the government of Italy under Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte imposed a national quarantine, restricting the movement of the population except for necessity, work, and health circumstances): the replacement of direct administration with home deliveries only partially compensated for the wiping out of this channel, to which is also directly linked the significant demand for food from foreign tourists, which disappeared with the cancellation of tourism, as documented by the ISMEA.

Other elements that transversely affect the agri-food sector concern personnel, including unskilled workers and manual labourers. Despite the adoption of measures aimed at reducing the impact, the presence of contagion risk in dairies, fruit, and vegetable processing centres, slaughterhouses, and meat processing centres as well as at transport companies has made operation of the supply chains more complex, in terms not only of procurement of raw materials and shipment of products and their delivery, but also with regard to higher production costs and lower working capacity. In some cases, the uncertain functioning of logistics services, especially international ones, has made it difficult for some companies to locate raw materials or consumables and packaging. Another problem to have emerged is that of finding services and spare parts for machinery, so as to guarantee maximum efficiency of activities both in agricultural and livestock farming and in food processing companies (for further information, see first ISMEA report on COVID-19 emergency).

2.1. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Agricultural Services and Food Market Trends

In terms of food consumption in the midst of emergency, the past weeks have proved extremely dynamic, not only due to the to-be-expected increase in purchases but also to changed consumer behaviour. For example, a trend towards the procurement of products with a long shelf-life (pasta, rice, preserves, milk, drinks, etc.) emerged, coupled with the strong tendency to conduct shopping online and almost exclusively with large-scale retailers. Where possible, this has been supplemented also with neighbourhood shops (fruit shops and butchers), both in order to move as little as possible and because they are sometimes considered safer than much more frequented environments, such as super or hypermarkets (first ISMEA report).

Going into more detail, the first ISMEA report revealed that the meat sector is the one that presents extremely diverse and unpredictable situations. Beef, for example, is struggling with a far-reaching reorganisation of distribution circuits and supply chains, in an industry which is heavily dependent on abroad. The scenario that emerges is that of an offer insufficient to satisfy domestic demand. In addition, prices on European markets fell, suggesting a possible increase in imports. In fact, the scenario that arose due to the excess availability of Italian meats on the shelves of the MMRs was further worsened by the pressure exerted by foreign meats, whose average price on European markets has dropped, making them very competitive against the national product. In the pig industry however, the emergency is believed to have led to a substantial reduction in production, above all due to reduced operation of the slaughterhouses, which had to reorganise their facilities to ensure the safety of their operators. In addition to the contraction in demand for the main products of the industry (due to the closure of the restaurant and catering channel), which is estimated at around 20%, there has also been a reduction in the prices of live animals due to an excess of supply. This results from the slowdown in the working rate of slaughterhouses and the processing industry. On the other hand, the poultry market benefited from a rise in demand, which saw it occupy a privileged position from the outset over other types of meat. Furthermore, this sector has exploited the advantages of a self-sufficient national market characterised by strong vertical integration, elements that have shielded it from problems related to dependence on external markets or other components of the supply chain. More than two months after the start of the crisis, the demand for poultry—after the first weeks during which it showed a marked increase—exhibited a significant downsizing, until it gradually returned to normal, with the consequent realignment also of the price at origin.

In the shellfish industry, the health emergency signalled a significant slowdown during the months of March and April, mainly due to the closure of the catering and restaurant channel and the drop in demand in the wholesale trade. Primary production mainly linked to the breeding of mussels and clams and to free fishing, despite not being subjected to direct limitations following government measures nevertheless suffered a sharp slowdown, due to the lack of demand from purification centres, whose only clientele came in the shape of the mass retailers, represented by supermarkets and hypermarkets. Some purification centres (i.e., infrastructures where depuration processes of shellfish are held in tanks of clean seawater under conditions which maximize the natural filtering activity to expel contaminants from the bivalves and to prevent their recontamination) were forced to close in March, while others reduced the purchase and subsequent sale of product by as much as 70–80%. In Italy, local marketplaces have also been hit hard by this crisis as a result of containment measures adopted by the various municipalities, making the entry of people subject to quotas. Shellfish prices have not undergone major changes; in general, there was a slight decrease linked to lower demand for the product. However, the most important limitation for this sector, mainly represented in Veneto by the breeding of the Ruditapes philippinarum clams, remains not having sufficient quantities of clam seeds. The production of clams in Veneto and in Italy more generally suffers heavily from this problem, which has hitherto been partially addressed by the import of seed from France or the United States [5,6]. This limitation has proved dramatic for Italian producers during the health emergency linked to COVID-19, where communications between different areas or countries have become more difficult, and in some cases, imports have been suspended (United States).

The uncertainty surrounding the availability of raw materials destined for the production of feed weighs on the livestock sector as a whole, particularly with regard to maize, for which Italy is increasingly dependent on imports. At present, there is a general rarefaction of the internal availability of raw materials due to difficulties of procurement from foreign markets.

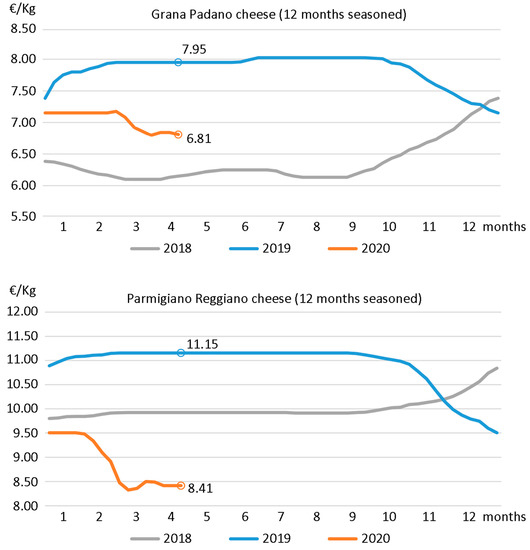

In the dairy sector, the emergency has led to a gradual slowdown in trade, favouring the creation of surpluses and the reduction of prices in the period of greatest production in the northern hemisphere (EU and US). On the domestic market, after the significant recovery recorded last year, the wholesale prices of the main cheeses have started to fall, showing a gradually larger decline with the new year. With the onset and spread of Coronavirus, especially in the areas of greatest production which were also those most affected by the health emergency in the first weeks—namely Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna—the prices of Grana cheese (one of the most famous and appreciated Italian cheeses all over the world) showed a sharp slowdown (−20% Parmigiano Reggiano and −10% Grana Padano in the February-April quarter, Figure 3) and the situation was also particularly critical for fresh cheeses and fresh milk, whose short shelf-life is difficult to reconcile with logistical and distribution difficulties, and with the total absence of demand from bars, patisseries, ice cream shops, etc. The drop in sales on the part of the dairies, and in some cases the halt in processing due to the absence of labour, influenced the collection of milk from the contributing farms, also causing the collapse of the spot market prices whose availability is growing strongly.

Figure 3.

Decelerated market trend with significant price drops for Parmigiano Reggiano cheese (−20%) and Grana Padano cheese (−10%) as a consequence of the national lockdown in the February–April quarter (source: ISMEA, Institute of Services for the Agricultural Food Market, Rome, Italy: for details on supply and demand economic models related to additional Italian food products see first COVID-19 emergency report (published on 30 March 2020) available at the following http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/10990 and second COVID-19 emergency report (published on 30 April 2020) available at the following http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/11016).

At the moment, the fruit and vegetable sector is operationally stable, but the critical issues it will shortly have to deal with are evident. One particular problem is the shortage of foreign workers, who have decided to return to their countries of origin, slowing down the harvesting and processing of vegetables. Indeed, at the moment, the most relevant issue is that of the organisation of the workforce, in view of the upcoming harvest period.

After a phase of initial difficulty (middle of March 2020), the wholesale fruit and vegetable markets found balance thanks to two phenomena: on the one hand, the need of the Mass Market Retailers (MMRs) to obtain supplies from this channel following the increase in final demand; on the other, the resumption of sales in the neighbourhood stores, which saw the number of customers grow owing to the long queues at supermarkets.

The wine sector, after confirming the great successes of 2019, started 2020 with troubling unknowns, to which was added the paralysis of the Ho.Re.Ca channel both in Italy and in the countries that constitute the main buyers of Italian wine, such as the United Kingdom and the United States. Making a very rough estimate, and taking into account only two months of difficulties worldwide, ISMEA estimates that exports worth almost a billion euros could be at risk, a loss that certainly would not be compensated, on the domestic market, by increased demand from the MMRs. The closure of hotels, agritourisms and restaurants—in addition to reducing the outlet for national production—has effectively cancelled a very valid promotional support structure for such products towards Italian and foreign buyers. Furthermore, in this emergency phase, the sector is facing some logistical difficulties concerning the supply of material for packaging.

The Italian olive oil sector has been experiencing structural and commercial difficulties for some time in truth, despite the prestige of its quality products. In regards to the market, Italy suffers from competition from Spain, especially for mass-market products, while it manages to free itself from the dynamics of the Spanish market on higher quality products. The current emergency does not seem to represent an element of particular criticality for the bottling phase, having occurred at a time when the companies were already well supplied. The attention is therefore directed to the agricultural phase, as we wait for signals that may give indications as to the future campaign.

As far as the cereal supply chain is concerned, the high level of imports is one of the main problems, with the agricultural phase increasingly lacking in raw materials, and the industrial phase increasingly appreciated on foreign markets. In the current context, Italian food processing industries are in a position of extreme vulnerability in regards to the procurement of raw materials, especially for products of foreign origin (European in particular) which, travelling by land, are more subject to restrictive measures or in general, to logistical problems. Even more critical is the context for feed mills and, consequently, for farms where it is not possible to keep abundant stocks. The health emergency does not however seem to have had an impact on the grain prices of the main cereals so far, although market tensions may arise in the coming weeks as a result of the difficulties in supplying foreign markets.

The second ISMEA report on trends in demand and supply of food products in the second month of the Coronavirus spread and National lockdown was published more recently (1 May 2020): http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/11016.

The agri-food chain during the COVID-19 emergency was monitored, from the initial production phase to that of retail sales, measuring the effects imposed by the total paralysis of the Ho.Re.Ca. channel and the elimination of tourist flows on the internal market, up to the contraction of exports.

In the production part of the chain, even when faced with the necessity of dealing with numerous critical issues, the sector still currently shows a good degree of resilience, capable of guaranteeing the supply of final markets, leaving aside exceptions represented by nurseries and fishing. However, especially for the fruit and vegetable sector, the difficulties of finding foreign labour for seasonal harvesting operations weigh heavily, while for the dairy and meat sectors (beef and lamb in particular) those deriving from the closure of the private and public restaurant and catering channel give greatest cause for concern. In addition, to the frustration of this important outlet, wine is also facing the collapse of demand in traditional client countries and then affecting the management of stocks in view of the next harvest.

Under the weight of this emergency, ISMEA notes a marked deterioration in the confidence of operators in the agri-food sector, resulting from deep concern over both the current situation and future prospects. The significant contraction of the agricultural confidence index is accompanied by a real collapse for the food industry. As a result of negative judgements with regard to the level of orders, the accumulation of stocks and production expectations, the confidence index has dropped by more than 26 points, to a full 43 points less than in the first quarter of 2019, and 27 below the level of fourth quarter 2019. The only figure with a marked positive sign in this critical period is that of household spending on food products, which continued to grow even in the second month following the onset of COVID-19. Retail sales of packaged food products have, in fact, had a double-digit increase compared to the same period of last year (+ 18%) and, overall, have also increased by an additional + 3% when compared to the first month of the emergency.

The main trends in this second month of lockdown are: (1) a boom in delivery, i.e., a significant increase (+160%) in home deliveries with a growth limit that was imposed not by actual demand, but rather by the ability to satisfy it (far lower); (2) a recovery on the part of the local commercial establishments that have also been quick to organise home delivery; (3) a substantial change in purchasing preferences by consumers who have changed from stockable products to primary ingredients (eggs, flour, oil, mozzarella, etc.—evidently cooking at home has become not only a way to “eat well” but also to spend time with the family); (4) a certain recovery in wine purchases, above all in the medium or medium-low market position; (5) possible store cupboard saturation and a likely liquidity crisis of some families, especially in the South.

2.2. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Agritourism and Forestry Sector Activities

The agritourism sector—closely linked to the local territories and cultural and historical traditions—deserves special mention. Indeed, in Italy, this sector has an estimated turnover of 1.4 billion euros, with a growth rate in the last three years of 7% (source: ISMEA). It was mainly foreigners who sustained the demand, with more than half of the overnight stays enjoyed by visitors coming mainly from Germany, Holland, France, and the United States. The extraordinary emergency situation that has arisen will have dramatic repercussions on the entire sector. The effect of COVID-19 on the agritourism sector—and on the whole Italian tourism sector—is quite simple to evaluate: from the beginning of the year to today, presence can be considered practically nil, and the persistence of the emergency could have similar consequences throughout the summer, if not perhaps for the whole of 2020. This scenario configures a very high loss of income deriving from foreign tourists, even if a part of this loss could be recovered through an increase in Italian guests during the summer. One of the main challenges for this sector is now how to encourage and promote Italian tourism on Italian soil.

In regards to the impact of COVID-19 on forestry sector activities, the most immediate effects were mainly felt, on the one hand, owing to the one-month veto of forestry activities and activities related to them in Italy, and, on the other, to the shutting down of wood processing activities, which are also based on imports of timber from abroad. Only with the entry into force of the Presidential Decree of 10th April 2020 could some activities related to the forestry sector reopen in an emergency state provided that they fall under ATECO codes A 02—Use of forest areas, C 16—Industry of wood and wood and cork products (except furniture) and manufacture of straw articles and woven materials (N 81.30—Landscape care and maintenance).

The forestry sector is heavily dependent on the demand for timber (construction timber, packaging timber, or timber/biomass for wood-based products and biomass for the production of energy from renewable sources), which is currently experiencing a strong contraction. Usage and processing of biomass connected to the civil and industrial energy sector were less affected by the freezing of related activities following the COVID-19 emergency. Complications have arisen in the market however due to the increased availability of forest biomass in this period as a result of recovering timber damaged by the Vaia storm (end of October, 2018), with a negative impact on both forestry companies and forest owners. The international market for wood products, both export and import, has suffered a sharp drop, along with the increase of potential difficulties for companies working with imports due to a reduction in the commitments of some countries following COVID-19 with regard to verifying the legal origin of the wood.

The woodland coppicing season, mainly producing cuts used for firewood, has been compromised in a large proportion of the mountain territory because of the prolonged pandemic lockdown, which also prevented the work activities typically carried out in an open environment.

With regard to the management of forestry sites and transport, the adoption of measures against the risk of contagion has forced companies to reorganise. This reorganisation has led to various difficulties, especially for the numerous small forestry companies that are not structured and organised in such a way as to be able to quickly transpose and implement the COVID-19 containment measures, nor are they able to contain the consequent increase in management costs within acceptable limits.

Specifically, forestry sites for improving territorial safety and recovering timber damaged by the Vaia storm (large areas of the North-Eastern Alps were affected) first registered a freezing of activities, followed by a slow return to recovery interventions. In particular, this sector is suffering from the absence of foreign companies engaged in the recovery process, as they cannot easily re-enter the Italian territory due to the obligatory quarantine period. Indeed, this is leading to a slowdown in the recovery of damaged wood, which entails an increased risk of propagation of extensive phytosanitary attacks on the parts of the forest left standing.

Other areas that have been strongly affected by the halt in activity and that are strictly related with the forestry sector are those connected with visiting the forest zones. The banning of activities in combination with the imposition of measures of social isolation have in fact led to the cancellation of tourism, recreational, and environmental education activities which, in ordinary conditions, provide a significant economic contribution, especially in mountain areas. In particular, activities normally carried out by educators and environmental guides in conjunction with schools have in fact been completely cancelled for the current school year. The multiple tourist and recreational facilities that support visits and outdoor recreational activities in forest and rural environments (e.g., adventure parks, refuges and bivouacs, huts, ski slopes and lifts, artistic installations, and outdoor museums, kindergartens in the woods, mountain therapy for the disabled, along with facilities for those who frequent the woods for mushroom picking, hunting and fishing, hiking and cycling, climbing, etc.) are no longer economically viable when taking into account the new rules on social distancing and hygiene. Their size and organisational abilities are not compatible with such restrictions. Forbidding the use of natural environments causes also important consequences from a social point of view, given the role that being in the forest environment plays for people’s psycho-physical and mental well-being.

3. Ideas, Guidelines, and Strategies for the Post COVID-19 Recovery in the Bio-Territorial and Agri-Food and Dimensions for a Transition to Economic, Social, and Environmental Sustainability

Some general considerations and personal observations through first-hand experiences lead us to think that policies to support competitiveness and sustainability (economic, social, environmental) at the regional and local level are needed, as well as system resilience nationally. In fact, by focusing on applied research and technology transfer, Italian/Regional universities could contribute to innovation and enhancement of the production chains of local businesses and at the same time help the establishment and implementation of business networks for specific areas. Action from the government institutions is needed for a substantial improvement in the public-private relationship, including through better coordination of the State with the individual Regions. The hope is that science and culture can return to play a central role in our society, as their main actors have the potential to make a decisive contribution to the recovery of our country. In this context, the strategic importance of public-private cooperation for safe re-opening and re-starting is evident (for example, in Veneto, several manufacturing associations like Assindustria Venetocentro, Confindustria Veneto, Unioncamere Veneto, and regional philanthropic foundations like Fondazione Cariparo have recently approved co-financing of the anti-Coronavirus “maxi-plan” for the Veneto Region and University of Padua with the Red Cross).

With regard to the political picture, we know that the “Cura Italia” (Heal Italy) Decree, whose bill was approved by the Chamber on 24th April, grants a series of immediate aid measures for businesses and workers, resulting in a total budget of around 25 billion Euros (decree no. 18/2020). With no doubt, it represents for the country an exceptional and powerful financial measure for the scope and urgency of its executive guidelines.

With the health emergency, it is widely stated by government authorities that it is easy to predict that in Italy there will be a uniform drive towards basic necessities (i.e., necessary goods including products and services that consumers will buy regardless of the changes in their income levels) to overcome the crisis. However, despite the importance of the agri-fish-foodstuffs sector, the “Cura Italia” Decree does not seem to have given it due recognition, providing for a limited package of measures in this regard.

Article 78 of the “Cura Italia” (Care Italy) Decree takes into consideration three main provisions: (1) to set up a fund to support agricultural and fishing enterprises (a first allocation aims to guarantee the total coverage of interest expenses on bank loans intended for working capital and debt restructuring, and to ensure coverage of the costs incurred for interest accrued in the last two years on mortgages contracted by the same companies); (2) raising the advances of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) contributions to farmers from 50% to 70%, a measure which, on its own, is worth more than one billion euros; (3) increase the Indigent Fund to ensure the distribution of food products to the most deprived members of society. There are other additional measures also aimed at supporting the agri-food sector, but they are on a smaller scale.

The April decree-law, later shifted to May, will be called the “Rilancio” (Relaunch) Decree-Law. It is the provision through which, after Cura Italia and the Liquidity Decree-Law, the executive now aims to get the country, brought to its knees by COVID-19, back on the road. This is a very significant decree worth 55 billion euros, which specifically also provides for an Emergency Fund to protect supply chains in crisis, with a budget set at 1 billion euros for 2020, aimed at implementing measures to rectify damage suffered by the agricultural, fisheries, and aquaculture sectors. The resources are mainly, but not exclusively, intended for plant nurseries, dairies, wine, livestock, and fishing and aquaculture sectors.

3.1. Food Security and Quality as a Lever for the Restarting of Businesses in Agriculture and a Faster Transition to Sustainability

As highlighted by the context analysis of the environment in which a business operates, the main critical elements caused by the pandemic affecting the agri-food economic system concern: (i) the change in demand for agri-food products at the local and world level, the worsening of the national capacity for self-supply of raw materials in the agri-food chain, the reduction of market space for national products on foreign markets, with particular reference to high-quality products; (ii) worsening in the availability of workforce for the agricultural sector and the risk of growth of undeclared work; (iii) the prospects with regard to the financial resources of the sector, in light of a possible reformulation of the CAP in relation also to the European Green Deal (for details, see COM/2018/392: Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules on support for strategic plans to be drawn up by Member States under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans), and also COM/2020/381: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions: A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy, and environmentally-friendly food system, available in the EUR-Lex portal at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/).

In regards to the first point, the pandemic has brought about a revolution in the balance of international markets. In addition to a brief crisis on the world markets affecting supplies of raw materials destined for the food supply chain, the most significant and long-term problems concern changes in the purchasing behaviour of final consumers, with a drop in the demand for national products on the foreign markets (shutting down of the Ho.Re.Ca. channel and tourism). This situation impacts the supply chains of the typical Made in Italy food industry (e.g., pasta, vegetable preserves, vegetable oils) as well as the quality products linked to the territories (Protected Designation of Origin PDO and Protected Geographical Indication PGI wines and food products). For example, Italy produces a surplus of about 75% for sparkling wines produced, 50% for pasta and tomato preserves, 65% for rice, 25% for hard cheeses, and 30% for fruit (statistics verifiable at www.dati.istat.it, ISTAT, 2020). This excess production requires the immediate ability to manage production supply, where possible right from the agricultural stage, by implementing economic policies for temporary relief of the market involving coordinated interventions for public/private storage or by directing products towards other industrial uses (e.g., distillation for wines). The possible areas of intervention concerning the management of agri-food markets involve managing the supply of quality products via the protection consortia and producer organisations (not only for PDO and PGI, but also for other geographical indications and traditional specialties, including the national systems of labelling and protecting Italian wines DOC and DOCG for their Designation of Controlled and Guaranteed Origin, and the Indication of Geographical Typicality or IGT for food products) and supply chain contracts within the food industry [7,8,9,10,11]. All this should be supported by innovative digital-selling channels [12] and global monitoring tools of the supply chain [13].

With reference to the second point, the pandemic has profoundly reduced the movement of people and it is expected that this situation will have consequences in the medium term, mainly because in the last years there have been a growing use of immigrant labour by the national and regional agricultural economy. The push towards immigrant work is partly justified by the low capacity of some parts of the agricultural sector to remunerate work in line with the national average, with the risk of an increase in the use of undeclared work. Putting aside mainly legal issues, part of the solution consists in matching supply chain bargaining tools with corporate social responsibility obligations [14]. In this context, assistance via collective bargaining models throughout the supply chain would enable a rebalancing of the bargaining power that the agricultural phase has with regard to industry, which has typically been very fragmented [15].

With reference to the third point, the policies now in place mainly concern short-term Community measures (Sure, Recovery fund, ESM or European Stability Mechanism) and strategic measures, such as the new CAP and the European Green Deal. In this context, it is necessary to be able to undertake two courses of action: one aimed at identifying the economic impacts of the pandemic, in the agri-food sector and related sectors, and the other at assessing the possible effect of policies aimed at protecting the environment and rural economies by guaranteeing the economic sustainability of agricultural enterprises with actions that also targeted at avoiding unfair competition of imported goods in terms of environmental and worker protection.

Food security could be a lever for the restarting of businesses in agriculture: sustainable and traceable supply chains involving high-quality products with guaranteed nutraceutical-health value, both supporting and protecting producers, and reassuring consumers with a direct impact on overall improvement of quality of life, understood as general well-being of individuals and societies. But we need to rethink the production chains, improving the organisation of work via the adoption of latest generation technologies, and working via the educational system to limit social and territorial inequalities. The hot topic of inequalities in Italy includes social fragmentation, regional differences, persistent gender and racial discrimination and the power of organized crime, and it calls for a new equitable social model, as reported by Pastorelli and Stocchiero ([16] and references therein, to read the full national report and the comprehensive Europe-wide report with all references, please visit: www.sdgwatcheurope.org/SDG10).

And as for investments for the development of infrastructures useful for safeguarding and protecting the territory and its biodiversity? Various aspects seem to assume particular importance, such as reducing bureaucracy and facilitating access to credit for agri-food businesses for their evolution/conversion into a sustainable agriculture model. It appears likely that more and more people will want food from plants that have been cultivated and animals that have been raised in “healthy” environments, with organic or at least non-intensive but sustainable methods, characterised by low chemical inputs [17,18]. Organic farming, through the use of biofertilizers, was shown to improve the antioxidant properties of fruits, but the data about proteins and micronutrients are rather contradictory. Nowadays, advanced devices and precision agriculture platforms allow more efficient and profitable cultivations, contributing more and more to reduce pest diseases and to increase the quality of agricultural products and food safety. Thus, the adoption of technologies applied to sustainable farming systems is a challenging and dynamic issue for facing negative trends due to environmental impacts and climate changes (see [18] and references therein).

Nutrition is also important in light of the consolidated scientific evidence that shows how diet can affect our state of health. Perhaps the need to make people more aware of the importance of variety in the diet, and the quality of the nutrients themselves, should be emphasised and conveyed more insistently, including with regard to individual genetics (nutrigenomics). In this context, it is easy to predict that functional foods, both fresh and processed, naturally rich in molecules with beneficial and protective properties for the organism, may become even more important in the nutritional practice since, if consumed as part of a balanced diet, such foods perform a preventive action for health. A food can be considered “functional” when its beneficial influence on one or more functions of the body has been demonstrated, in addition to having adequate nutritional properties, so as to be relevant for a state of well-being and health or for reducing the risk of a disease. An emerging and relevant science, and one which is closely related to the concept of functional foods, is that of nutrigenomics, which studies the relationship between genome and diet at an individual level [19]. This area of research aims to delineate the interplay between nutrients intake and the reciprocal pathologies with the human genome. Nowadays we know that nutrigenomics has the potential to individualize nutrition, reminiscent of pharmacogenomics and the individualization of drug use [20].

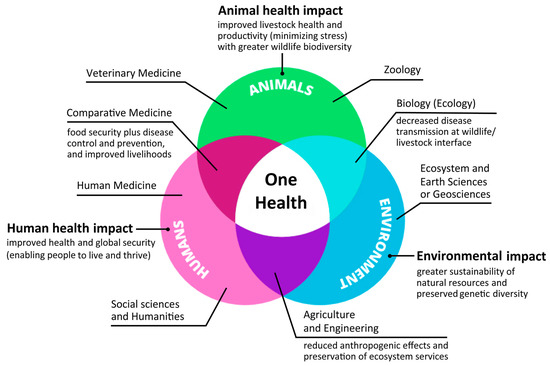

In these dramatic months, we learnt from medical doctors that in case of contagion, deterioration is brought about by a state of deep inflammation that impairs the immune system. And therefore, in addition to strict compliance with the rules of hygiene and social distancing, what we can do is try to strengthen our immune system, which is closely linked to the intestinal microbiota, i.e., the complex of microorganisms that regulate many functions and generate an anti-inflammatory response against pathogens. Specialists claim that 70–80% of the body’s immune cells are located in the intestine and, therefore, the efficiency of this activity depends precisely on the variety of nutrients and the quality of the foods that we ingest (this field suggests a link with the medical health dimension and veterinary-medical food safety) [18]. It is clear that the welfare of farm animals must necessarily fall within the perspective of the so-called “One Health”—the fully integrated vision of human, animal, and environmental health (Figure 4). More specifically, it represents a multidisciplinary and synergistic effort of several health science disciplines and professionals, working locally, nationally, and globally, to attain optimal health for people, domestic animals, wildlife, plants, and our environment [21]. The core competencies and domains in One Health education were presented in a number of prospective papers [22,23]. Here it is worth mentioning that the reduction in the administration of medicines by veterinary surgeons, which can only be made possible via a strict improvement of the hygienic-sanitary conditions of breeding environments, can contribute to solving or at least reducing the problem of antimicrobial resistance [22].

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the One Health approach finalized to ensure the well-being of people, animals, and the environment through collaborative problem solving-locally, nationally, and globally. This approach recognizes that we live in a global society with threats linked to climate change, human population growth, changing land use, and emerging pandemics (modified from UC Davis One Health Blog, https://www.ucdavis.edu/one-health/and enriched with relevant information).

The affections of animals that are normally treated in the industrial production system—which remains, for quantitative supply needs, the only system that can currently be pursued on a national scale—are mainly ascribable to “technopathies,” i.e., to conditions that are particularly stressful for specific systems (mammary, digestive, musculoskeletal, and respiratory systems) and therefore for the homeostasis of the individual.

As state of the art, the University of Padua (https://www.unipd.it/en/) is already undertaking research that bridges the gap between human and veterinary medicine, aimed at understanding the possible relationship between animal antibiotics and the creation of strains of resistant microorganisms, also and above all at an environmental level (and thus through the dispersion of animal waste). However, antibiotic therapy is not the only solution to animal technopathies; a wide range of drugs is currently used to recover homeostasis in an unbalanced system. Therefore, greater respect for the physiology of the farm animal will certainly represent the best therapeutic approach in a holistic sense, just as for mankind. However, in this context it should be also specified that the latest report published by the EMA (European Medicines Agency, for details see https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/sales-veterinary-antimicrobial-agents-31-european-countries-2017_en.pdf) shows that European countries have already started to reduce the use of antibiotics in animals, with a decrease in their sales in Europe of 32% in the period from 2011 to 2017, confirming a trend which could become indispensable from the perspective of “One Health.” One Health perspectives are growing in influence in global health. It is presented as being inherently interdisciplinary and integrative, drawing together human, animal, and environmental health into a single dimension. Recently, Fraser and Campbell [24] emphasized that humanity has arrived at a point where food systems must reconcile the need to produce enough healthy and affordable food with the equally important imperative of preserving the ecosystems on which we depend for life. We must transition through the One Health vision into the new Green Revolution of the mid-20th century for reconciling food production with planetary health [24].

Respect for economic parameters in the quantitative maintenance of production, combined with respect for animal physiology, requires a significant change of scientific-cultural paradigm in modern animal husbandry, which only a push from research can satisfy, but which would certainly represent a possibility for relaunching quality and the interest of consumers in local/national productions of global reach. A closer inspection reveals that this presentation of entanglement is dependent upon an apolitical understanding of three pre-existing separate conceptual spaces that are brought to a point of connection [25].

There is no doubt that improving the supply chain should also be understood as concomitantly enhancing food safety and certifying the healthiness of foodstuffs of both animal and vegetable origin, enabling the expansion of current analytical limits and above all broadening the interpretative horizons, also in light of new knowledge, in order to analyse the critical issues by rationalising the available resources and at the same time promoting faster and more incisive corrective intervention times.

3.2. Agriculture 4.0: The Need of New Breeding Techniques and Precision Farming Systems

Very interesting ideas from a recent article by Acquafredda and Cuonzo [26] about the strong link between coronavirus and agriculture, for whose resolution the authors suggest full transparency of production chains and highlight it represents also an ethical chance for Italy. The COVID-19 pandemic has, in just a few weeks, undermined the paradigm of globalisation in every economic sector, including the primary sector of agriculture. Here the impact of the virus acts on two fronts: the first is the structural lack of self-sufficiency of Italian agricultural production (especially in the strategic sector of wheat) and the consequent difficulty in procurement of raw materials for the production of essential goods (bread and pasta) following the reduction of world trade; the second concerns the sudden scarcity of the workforce, especially seasonal, due to the global lockdown and closure of the national borders.

The fact that Italian agriculture is increasingly dependent on foreign imports is shown by the data on corn, wheat and pulses. Between 2012–2017, domestic production of corn underwent a 19% reduction with an increase of about 68% in imports, especially from Hungary and Austria. External dependence for pulses—a primary source of vegetable proteins—is very strong with over 90% being of foreign origin, coming above all from the United States and Canada. Common wheat saw an increase in imports of 15%, while the increase in imports of durum wheat (55%) is even more significant compared to a production decrease of around 6%. At the moment, the Italian pasta industry’s demand for durum wheat is around 6 million tons compared to a national production of about 4. Despite this growing imbalance, in Italy agricultural businesses continue to decline (−1.2% in 2019) [26].

In addition to making procurement of raw materials from abroad more difficult and expensive, the Coronavirus emergency has also drastically decreased the availability of seasonal workforce (that is not consistently present in the territory in a stable way) due to restrictions on the movement of people and closing of the borders. According to Confagricoltura estimates, at least 200,000 agricultural workers are immediately necessary for the cultivation and harvesting of cereals and fruit and vegetables. The difficulty of finding workforce—which before the crisis was considered unlimited—definitively constitutes a crisis for an archaic model of industrial relations in agriculture that still persists, especially in the south of the country.

The state of emergency affecting the primary sector of agriculture requires well-targeted and measured interventions on the part of the institutions, in concert with the many innovative companies in the sector. If the right decisions were made and targeted actions taken quickly, the current crisis could become a real watershed moment for one of the strategic sectors of the future, giving birth to the so-called Agriculture 4.0. This term refers to the next big trends facing the industry and primary sectors, according to a multi-perspective and -disciplinary approach, including a greater focus on precision agriculture (e.g., sensor technologies, satellite navigation systems, and positioning technologies), the internet of things (IoT) and the use of big data to drive greater business efficiencies in the face of rising populations and climate change [27]. The future therefore requires, on one hand, platforms and technologies that allow arable lands and livestock farms to use advanced technologies in a mutually reinforcing and interconnected way, with the aim of making production more efficient and sustainable. On the other hand, this is a revolution in agriculture still limited to a few innovative firms. In fact, despite the real advantages of Agriculture 4.0 for large enterprises, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often face complications in such innovative processes due to the continuous development in innovations and technologies. Policy makers should plan strategies and call for proposals with the aim of supporting SMEs to invest on these technologies and making them more competitive in the marketplace [28].

The most important challenge is not only qualitative but also quantitative: producing more and of higher quality, on increasingly smaller terrains (“more with less”) is possible, as demonstrated by the experience of Israel and other countries such as Holland [29]. Next-generation farming promises to increase the quantity and quality of agricultural output while using less input (water, energy, fertilisers, pesticides, etc.). The aim is to save costs, reduce environmental impacts, and produce more and better food products. The way forward is technology in the best sense of the word. We need to invest in research and development, and in the technology transfer so that overall innovations in agriculture may hasten transition to sustainability and increasingly assist farmers in their work.

For example, in the vegetable, crop, and fruit plant sector, the creation of new varieties which are resistant or tolerant to climate change, are adaptable to sustainable production systems, and which ensure greater unit yields are urgently needed. New technologies for genetic improvement (new breeding techniques, NBTs, including cisgenesis and genomic editing) of crop plants against biotic and abiotic stresses [30], and precision agriculture (farming management concept based on observing, measuring, and responding to inter and intra-field variability in crops) are the answer to this specific need [31]. In particular, the use of NBT platforms in plant biology is opening up a new era of genome editing-mediated crop breeding in the most agriculturally important species, including vegetables and fruit trees [32,33]. Application of these techniques, which requires an exhaustive knowledge of the genome of crop plant species, will certainly allow the development of new varieties suitable to overcome the limitations of conventional breeding methods and their multi-year length, reducing the risks of the first generation of genetic engineering tools [34]. It is worth mentioning that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing protocols (i.e., clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated 9 (Cas9)) are useful to silence in a genome or replace from a genome specific DNA sequences in targeted regions by engineered nucleases [35,36,37]. In other terms, applications include both “gain-of-function” (editing/replacing) and “loss-of-function” (silencing) strategies. Finally, and most importantly, this genome editing approach allows a pre-determined and site-specific genetic modification, which is reproducible and guarantees the total absence of exogenous DNA in the plants of the resulting edited varieties [35].

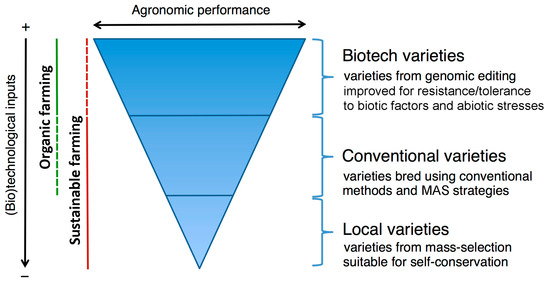

The combination of rapidly advancing genome-editing technologies with breeding and farming methodological advancements will greatly increase crop yields and quality, and overall sustainability. In the scenario of a new agriculture, i.e., Agriculture 4.0, we are confident that NBTs are going to play an important role in order to make productive processes more sustainable under environmental, economic, and social points of view (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A feasible scenario for future agriculture in Italy: a comparison among local varieties (i.e., landraces), conventional varieties (i.e., breeding based on phenotyping and genotyping by means of marker-assisted selection, MAS) and biotech varieties (i.e., genetically edited varieties) in terms of agronomic performances and in relation to (bio)technological inputs that make them suitable to sustainable and/or organic farming systems.

Furthermore, new trends in agricultural practices and recent sanitary emergencies have made producers and consumers more demanding about agri-food authenticity, with a concurrently increasing interest for food origin, healthiness, and nutraceutical properties [38]. Modern technologies based on genomics and bioinformatics represent very efficient tools for assessing the genetic authenticity and genetic traceability of food products and beverages. Current DNA-based diagnostic assays are suitable and reliable molecular tools for the genetic identification and authentication of plant foodstuffs, fresh and processed meats, and fishery derivatives by means of DNA barcoding or DNA genotyping methods. These are actually essential tools to vouch for quality controls of food products, to guarantee food traceability, to safeguard public health, to uncover food piracy, and to valorise local and typical agro-food production systems, including valuable vineyards/wines [39] and olives/olive oils [40].

Self-sustained production becomes more important: In the shellfish supply chain it is necessary to ensure the production of clams is no longer dependent on the import of seed clams from foreign countries, and is less conditioned by the availability of natural seed, which in recent years has been particularly scarce due to the climate changes that have modified the environmental conditions. To this end, essential steps in consolidating production and reducing loss of product include the production of seed in dedicated structures (hatchers), and breeding of the juvenile stages (pre-fattening) via structures and methodologies optimised for the characteristics and particular situation of our lagoons. The creation of structures designed to perform these functions would allow the implementation of genetic improvement programs, in particular those aimed at selecting animal lines better adapted to climate change. Such programs have so far been impossible since most of the seed does not derive from controlled reproduction.

Italy has the potential to become, together with France, Holland, Israel, and California, a global player in varietal research and development. To this end, it is essential to create, or reinforce where it is already in existence, collaboration between companies in the territories and university research centres for experimentation and the creation of new varieties—suitable for specific production environments/cultivation methods—which once registered can give rise to cash flows in terms of royalties via the granting of licenses to other producers in the world. By way of an example, at the moment, Italian producers of seedless table grapes pay important royalties to foreign companies. We must absolutely reverse the trend. In addition to the “home-made” genetic improvement, a sector in which the Italian school has a long tradition, the other essential aspect, as already mentioned, is the use of the so-called precision agriculture via the use of advanced technology, from the collection of soil biochemistry data to more accurate weather forecasting. Here too, cooperation is essential between companies, universities, and institutions to give rise to the creation of certified supply chains including via blockchain.

Existing best practice should be extended: supply chain contracts which, on the one hand, encourage local production via the provision of specific premiums to farmers based on product quality and, on the other, cover supply risks in the food industry.

None of this will be sufficient if the culture of agricultural work is not deeply changed. From the servile model that raged in the twentieth century—from illegal recruitment to the cruel use of immigrants as modern slaves deprived of all rights—it is now necessary to move on to new industrial relations that focus on the agricultural worker as a bearer of know-how. Many immigrants have a cultural and intellectual potential that would make them fully suitable for more complex tasks. The road is long, but it would be necessary, for example, to design new, more flexible employment contracts that are less burdensome for the company, accompanied by benefits such as housing that favour staying in the territory throughout the year. With the ultimate goal of having plant and animal production chains that are certified also from an ethical point of view. This is an essential point: the consumer (from fashion to food) after Coronavirus will be increasingly attentive to the transparency of supply chains and to the health/quality of the products, but also to the integrity of the same supply chains from an ethical and moral point of view. A potential risk to take into account is that poverty may reduce interest in product information for the lower class. Through the blockchain, the consumer will be able to verify these characteristics of the product, which will form an essential element of the choice. This means that the logic of environmental sustainability and respect for human individuality at work will become the new paradigms of consumption, in addition to the no longer deferrable need to recover the farming and cultural traditions of the territories (heritage).

In this sense, one should not underestimate the psychological impact of the virus pandemic on the perception of science from the general population. A consistent part of the food buyers had a long-standing prejudice against the use of GMOs and technology sensu latu [41] applied to agriculture. This tendency was common in people who had a negative opinion on vaccines [42,43] and the use of scientific methods to improve health and food production. In the wake of the wide consensus received by medical doctors, nurses, and medicine during the fight with the virus, several formerly prejudiced individuals and associations have now started to accept a more modern view of science, including the whole agri-food production system. For instance, the first collaboration agreement on the use of NBTs in agriculture has been signed on 17 June 2020 between the Italian Society of Agricultural Genetics (SIGA) and the National Confederation of Direct Growers (Coldiretti, the largest Italian association representing and assisting agricultural entrepreneurs). This is an unprecedented agreement that paves the way for a fruitful collaboration between scientists and farmers aimed at exploiting the so-called “assisted evolution technologies” for breeding new varieties suitable for next-generation farming towards an overall sustainability of agricultural systems and food productions (for details on the agreement, see www.geneticagraria.it/attachment/Download/Accordo_Coldiretti-SIGA.pdf). An increased percentage of the population may now look with renewed trust at the progresses in crop and animal production science, and—as a side effect—actively reduce environmental pollution by chemical pesticides by the use of genetically improved varieties of cereals and vegetables [44,45,46]. Although the pandemic hit heavily all sectors of the society, a post-war-like effect may actually accompany the recovery phase and lead to technological steps forward and improvements impossible to conceive before its advent. The next vaccination campaigns may be useful to understand whether this opportunity will be taken. For instance, resistance to NBT diffusion and consumer distrust will be challenged by current awareness wave, so that these new technologies and their derived genome-edited varieties (showing resistance or tolerance to pests and pathogens, and environmental stresses or improved quality traits) may become, in the post-pandemic era, the equivalent of the antibiotics diffusion after the Second World War.

We therefore need a new vision and immediate action by all stakeholders—primarily government and regions—so as to transform Italian agriculture and animal husbandry into a great opportunity: mapping out its fate, rather than considering it as a sector to be abandoned to its ongoing decline.

3.3. EU Orientations to Support Research and Innovation towards a Strategic Plan for the Primary Production and Environmental Sustainability

Beyond Italy, there is the impact of the new Coronavirus on the European agricultural supply chain. The crisis triggered by the spread of this virus has shown how fragile and unsustainable our European food supply system is. EU Institutions and Member States should act now, to make sure that the food we eat does not result from the exploitation of people and the planet, and so as to build a fairer and more sustainable food system. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has recently documented the urgent need of concrete and concerted actions required to realize key global agendas: “All main actors need to contribute to a common understanding of the major long-term trends and challenges that will determine the future of food security and nutrition, rural poverty, the efficiency of food systems, and the sustainability and resilience of rural livelihoods, agricultural systems, and their natural resource base” ([47] by da Silva, Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, see FAO 2107 Report, p. 7).

The situation of agri-food workers needs to be addressed urgently during the COVID-19 pandemic. The working and living conditions of many workers along the food, and in particular agricultural, supply chain are generally below standards. In the current situation, workers are seriously exposed to the risk of contracting Coronavirus. The EU Institutions and Member States should do everything necessary, including the mobilisation of additional funding, to ensure support for workers in the agri-livestock sector. In particular, Italy needs the following actions:

- (1)

- Transform the new Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) to make it both socially and environmentally sustainable: the EU’s policy has so far favoured unsustainable agricultural practices and its social dimension has focused almost exclusively on farmers, but not on agricultural workers. In line with the European Green Deal, the new CAP should strengthen environmental conditions for the granting of agricultural subsidies.

- (2)

- Include a focus on workers in the Farm to Fork strategy: the European Farm to Fork strategy should pay more attention to workers in the agri-food sector and ensure that the benefit is distributed more evenly along the food chain. The EU Treaty makes this objective clear by stating that the CAP should guarantee “a fair standard of living” for the wider “agricultural community” (Article 39 TFEU).

Finally, we cannot ignore the double global emergency that we are facing: environmental emergency plus pandemic emergency. On 28th November of last year, the EU Parliament proclaimed the existence of the “global emergency” of the climate change. A few months later, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived and the prospect changed radically: now we are called to face two global emergencies. An analysis is therefore required with regard to the possible relationship between these two phenomena, starting from a first question: is there a connection between climate change and pandemics? Numerous studies affirm it (see Watts et al. [48] and references therein, e.g., “Climate change affects the distribution and risk of many infectious diseases,” Indicator 1.4: climate-sensitive infectious diseases p. 1845, see also [49]). In summary, the emigration of wild species deriving from the contraction of their respective habitats—in part also due to the effect of climate change—increases the probability of a leap of pathogens towards species never met before, eventually arriving at humans (see “The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change”). Therefore, the fight against climate change is also fully relevant to actions aimed at preventing the risks of new pandemics.

Recently, Merola [50] published an interesting vision article by which the author tries to reverse the reasoning: What effects can the COVID-19 emergency have on the fight against climate change? In his view, there are two main underlying risks: first, the tragic and immediate impact of the global pandemic and the temporary reduction of pollution linked to the contraction of economic activities may obscure the perception of climatic urgency; second, a humanity that has been afflicted and is now concentrated on repairing the economic and social damage of the global pandemic may no longer find the economic and mental resources to face the substantial investments and the inevitable renunciations necessary for the environmental challenge.

In short, with the crisis owing to the pandemic emergency, the climatic emergency could fade into the background. If this happens, it would be hazardous: the IPCC (UN) Special Report 2018 on “Global Warming” sets the timeframe for an increase of 1.5 °C in the average temperature of the planet at 15–20 years. A balance must be reached between the need for farming and animal production and the environment, and in this sense the present pandemic taught us a lesson to remember [51].

Significant in this regard is the lesson that the history of the current pandemic provides us with. According to Merola, COVID-19 does not come out of nowhere and is not unexpected. Humankind, dispassionate by choice or unable to govern critical dynamics of mother nature, was already subjected to several rehearsals before withstanding the decisive attack: between 1980 and 2013 there were about 12 thousand epidemics that affected 44 million people (source: World Health Organization). The risk of planetary pandemics has been the subject of many international studies but has always remained on the outside of global economic policy-making (Watts et al. [48] and references therein).