Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or Reality?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

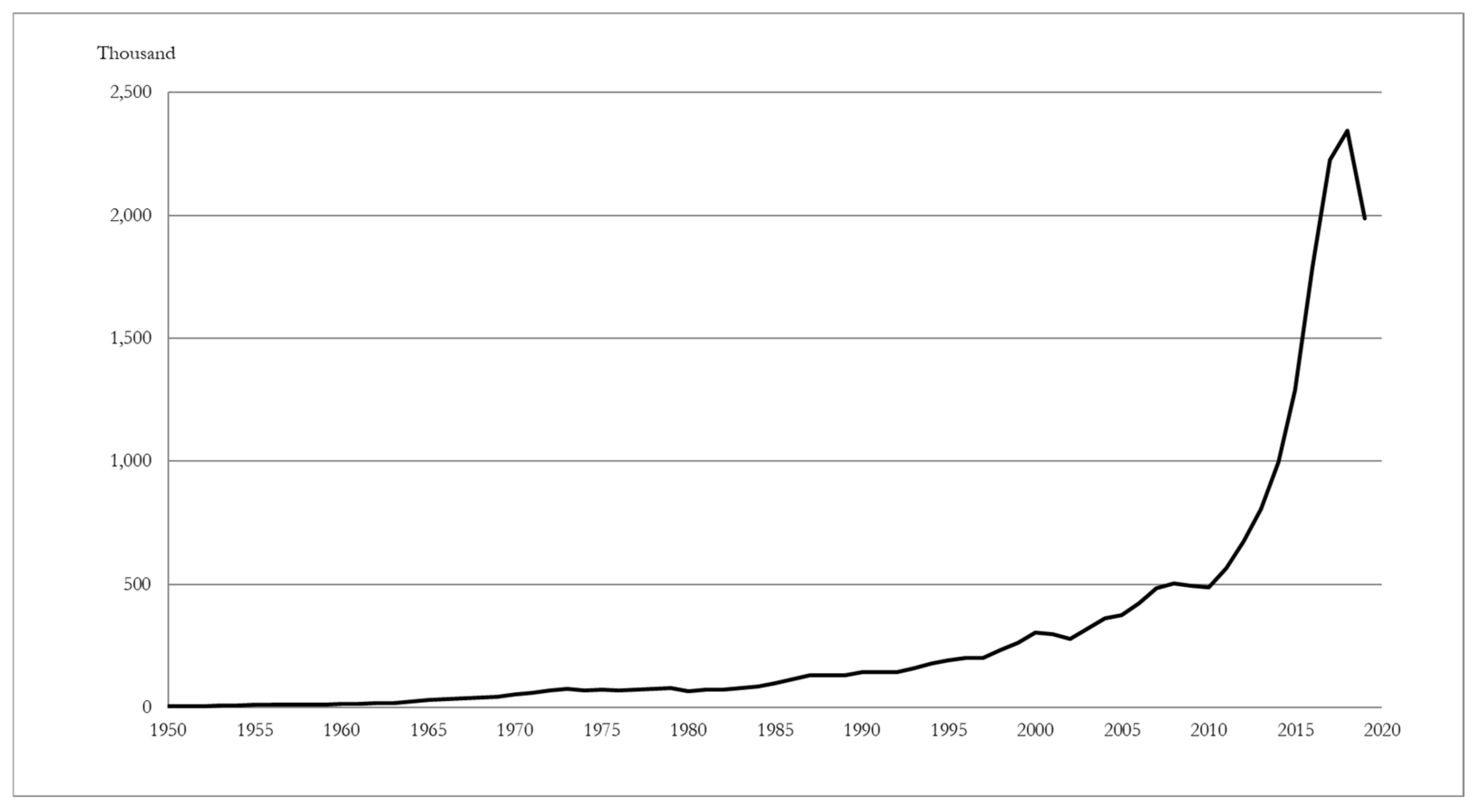

2. Background

2.1. The Overtourism Concept and Common Pool Resources

- Ownership of resources is held in common, including via public ownership, or shared by a large number of owners.

- Individual users utilize the resource for personal benefit. It is often in the interest of commercial users to utilize the resource as much as possible to obtain additional revenue. However, the loss due to overuse, which may be a financial loss, a reduction in personal satisfaction level, or a reduction in access, is shared among all users. This can lead to overuse of the resource.

- No private individual is usually willing to invest with the aim of improving the resource as there is no guarantee that the return to investment would go back to the private investor. This is why government is usually the institution responsible for improvements, either via direct investment or regulation.

- Control of access to the resource is difficult. This can be for a variety of reasons. For example, boundaries may be difficult to delineate and police, the size or area of the resource may be very large, or control may not be accepted due to political reasons, including that it is a common and/or public space.

2.2. Managing Overtourism

2.3. Media Discourses and Destination Change in the Era of Overtourism

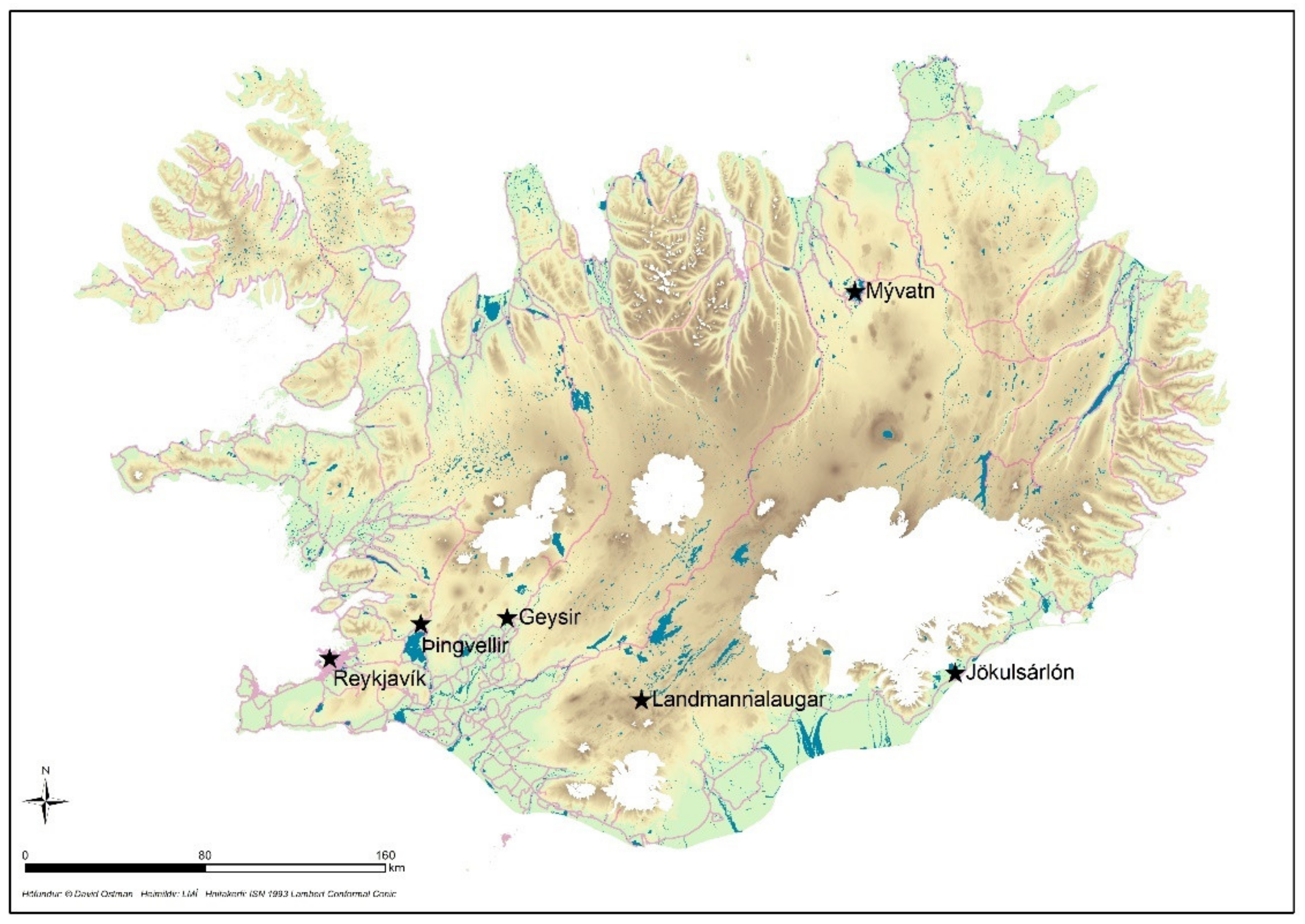

3. Study Area

4. Methods

5. Results

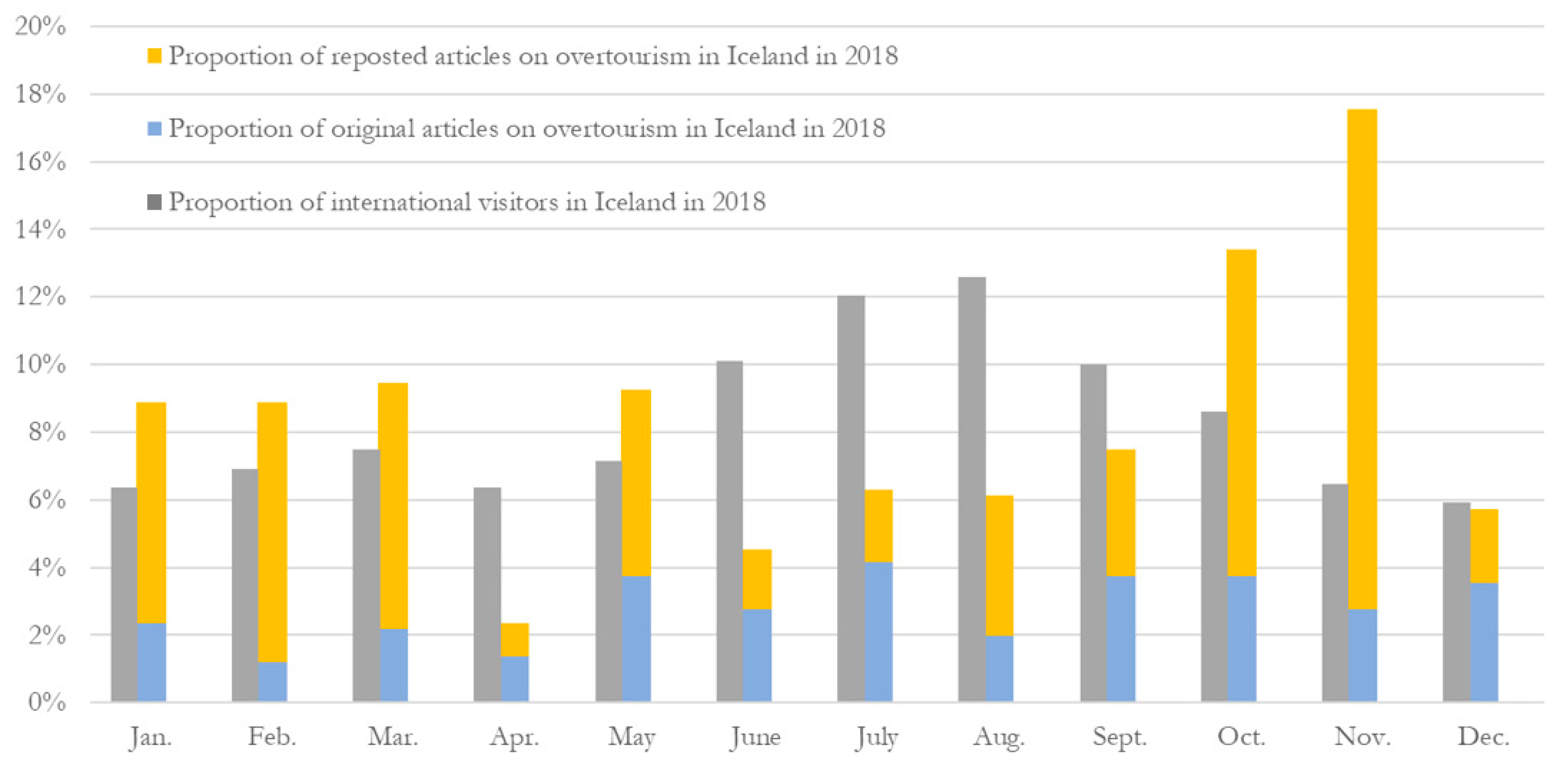

5.1. Media Results

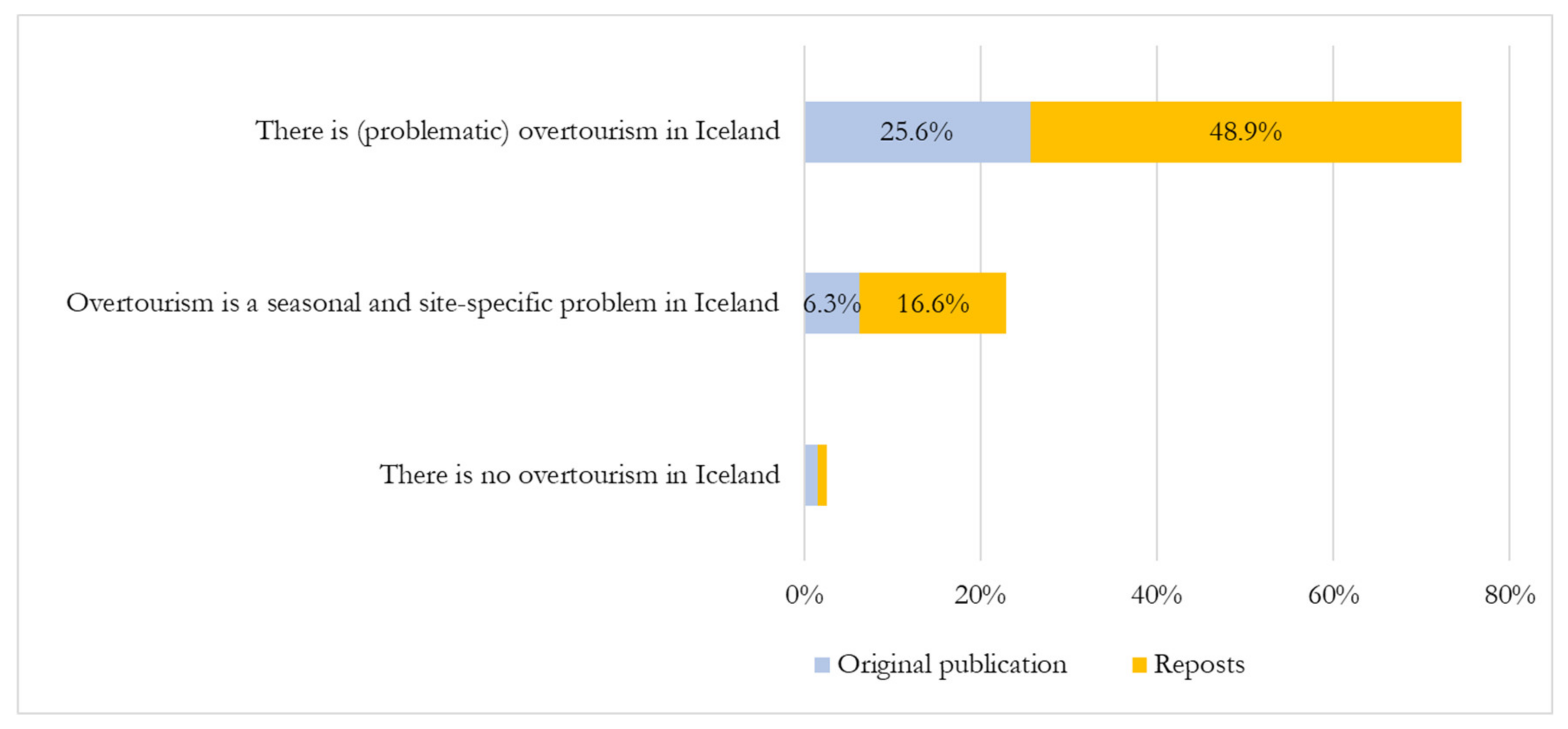

5.1.1. The Media Portrayal of Tourism in Iceland as Overtourism

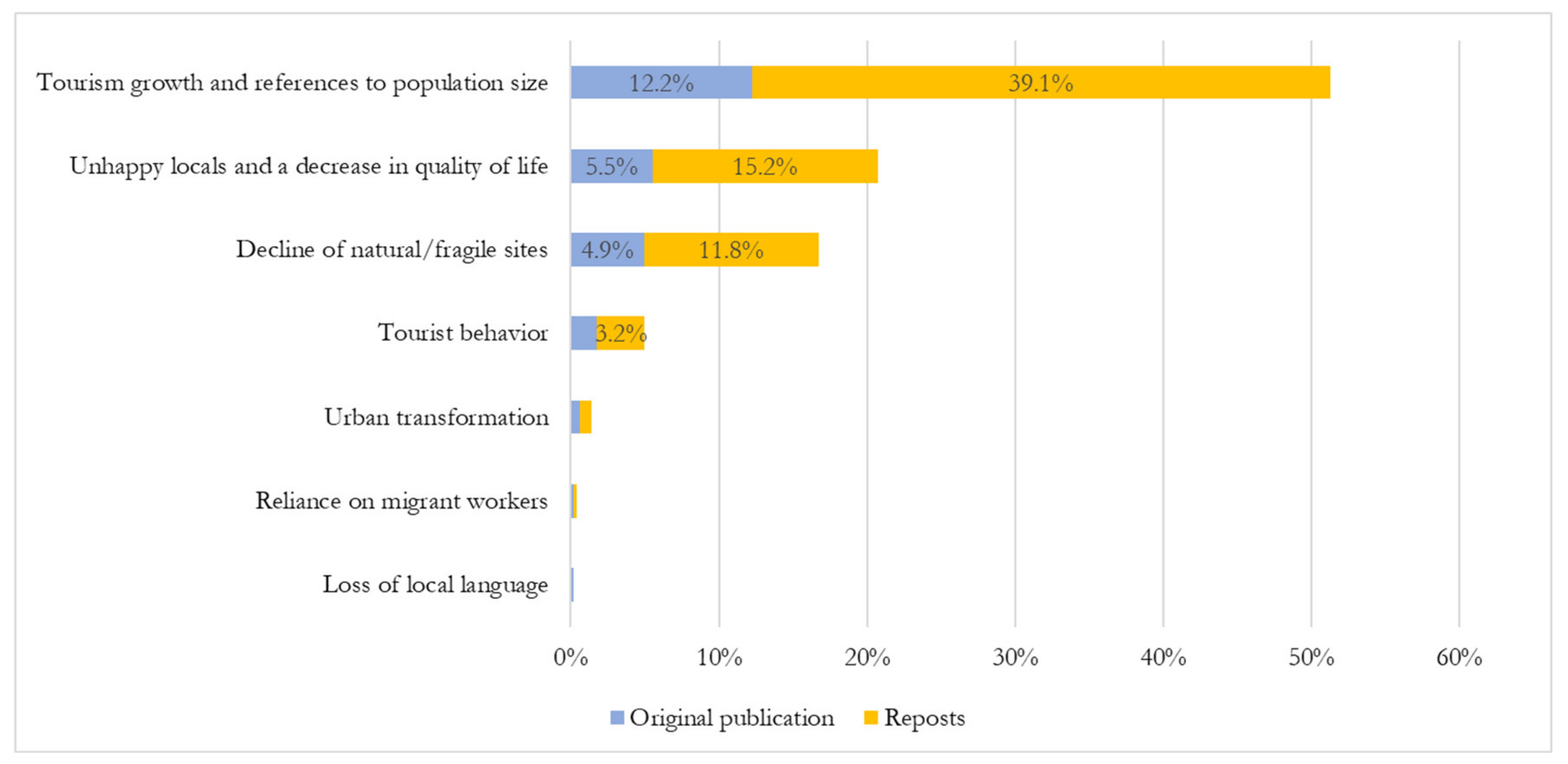

5.1.2. The Manifestations of Overtourism in Iceland as Presented by the Media

5.1.3. The Reasons for Overtourism in Iceland

5.1.4. Reactions to Overtourism

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J.M.; Novelli, M. Introduction. In Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; Milano, C., Cheer, J.M., Novelli, M., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Adie, B.A.; Falk, M.; Savioli, M. Overtourism as a perceived threat to cultural heritage in Europe. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1737–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D. The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B. More People Will be Visiting Portugal in 2019—Here’s Why. Cntraveler. 5 December 2018. Available online: https://www.cntraveler.com/story/more-people-will-be-visiting-portugal-this-year (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Murphy, J. Pastoral Charm—And a Five-Star Boutique Hotel—Cast a Spell in the Heartland of Alentejo, Portugal. Houston Chronicle. 29 October 2018. Available online: https://www.houstonchronicle.com/life/style/luxe-life/article/Pastoral-charm-and-a-five-star-boutique-hotel-13349727.php (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Stewart, T. Places Struggling with Overtourism and Where To Go Instead. Airfarewatchdog. 15 January 2020. Available online: https://www.airfarewatchdog.com/blog/44254789/5-places-struggling-with-overtourism-and-where-to-go-instead/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Icelandic Tourist Board Numbers of Foreign Visitors to Iceland. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/en/recearch-and-statistics/numbers-of-foreign-visitors (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421152 (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- UNWTO. Resources. Tourism Data Dashboard. Global and Regional Tourism Performance. Key Tourism Indicators. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/global-and-regional-tourism-performance (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Ali, R. The genesis of overtourism: Why we came up with the term and what’s happened since. Skift. 14 August 2018. Available online: https://skift.com/2018/08/14/the-genesis-of-overtourism-why-we-came-up-with-the-term-and-whats-happened-since/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Adams, C.; Coffey, H. Where Not to Go in 2020. Where to Leave off Your Bucket List Next Year. Independent. 30 December 2019. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/where-not-to-go-2020-iceland-bruges-kyoto-venice-machu-picchu-a9250771.html (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Mack, B. 22 Destinations that were ruined by tourists over the past decade. Insider. 15 January 2020. Available online: https://www.insider.com/places-ruined-by-tourists-over-the-past-decade-2019-12?fbclid=IwAR0U5aPvk853ilEGWnmJEmywIKVuqRbP9yJ26L8FlnwGq-MZFlJRxAzSPi4#iceland-has-had-a-moment-but-the-attention-brought-by-the-likes-of-game-of-thrones-star-wars-and-justin-bieber-has-had-consequences-1 (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Runnström, M. Assessing hiking trails condition in two popular tourist destinations in the Icelandic highlands. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2013, 3–4, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Óladóttir, O.Þ. Erlendir Ferðamenn á Íslandi 2018: Lýðfræði, Ferðahegðun og Viðhorf (International Visitors in Iceland 2018. Demography, Travel Behaviour and Attitudes); Icelandic Tourist Board: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Iceland. Population. Available online: https://statice.is/publications/publication/inhabitants/population-development-2018/ (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- The World Bank. International Tourism, Number of Arrivals. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- The World Bank. Population, Total. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Modak, S. How the Azores Will Hold off the Crowds and Stay a Natural Wonder. Cntraveler. 24 October 2018. Available online: https://www.cntraveler.com/story/how-the-azores-will-hold-off-the-crowds-and-stay-a-natural-wonder (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Butler, R.W. The influence of the media in shaping international tourist patterns. Tour. Recreat. Res. 1990, 15, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Travel safety, terrorism and the media: The significance of the issue-attention cycle. Curr. Issues Tour. 2002, 5, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Stefánsson, Þ. Senses by Seasons: Tourists’ perceptions depending on seasonality in popular nature destinations in Iceland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Amaduzzi, A.; Pierotti, M. Is ‘overtourism’a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Curr. Issues Tour. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. Overtourism: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment. 2019. Available online: https://responsibletourismpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/TWG16-Goodwin.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oklevik, O.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Steen Jacobsen, J.K.; Grøtte, I.P.; McCabe, S. Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: A case study of activities in Fjord Norway. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1804–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phi, G.T. Framing overtourism: A critical news media analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiroglu, O.C.; Hall, C.M. Geobibliography and bibliometric networks of polar tourism and climate change research. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, F.M.Y.; Rivera, J.P.R.; Gutierrez, E.L.M. Framework for creating sustainable tourism using systems thinking. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G.P. Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. J. Travel Res. 2011, 20, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning, 2nd ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Briassoulis, H. Sustainable tourism and the question of the commons. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 1065–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, R.G. The “common pool” problem in tourism landscapes. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H. The Challenge of Overtourism; Responsible Tourism Partnership: Faversham, UK, 2017; Available online: https://haroldgoodwin.info/pubs/RTP’WP4Overtourism01′2017.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Manning, R.E. Parks and Carrying Capacity. Commons without Tragedy; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Lew, A.A. Understanding and Managing Tourism Impacts: An Integrated Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourism area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Ponsford, I. Confronting tourism’s environmental paradox: Transitioning for sustainable tourism. Futures 2009, 41, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L. Special Report on a Wildlife Study of the High Sierra in Sequoia and Yosemite National Parks and Adjacent Territory; US Department of the Interior National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.C. The Recreational Capacity of the Quetico-Superior Area; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Lake States Forest and Experiment Station: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Wagar, J.A. The carrying capacity of wildlands for recreation. For. Sci. 1964, 7, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, M.P.; Vaske, J.J.; Whittaker, D.; Shelby, B. Toward an understanding of normprevalence: A comparative-analysis of 20 years of research. Environ. Manag. 2000, 25, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graefe, A.R.; Vaske, J.J.; Kuss, F.R. Social carrying capacity: An integration and synthesis of twenty years of research. Leis. Sci. 1984, 6, 395–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, J.L.; Murdock, W.E. Social norms in outdoor recreation: Searching for the behavior-condition link. Leis. Sci. 2002, 24, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, R.E.; Valliere, W.A.; Wang, B. Crowding norms: Alternative measurement approaches. Leis. Sci. 1999, 21, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Neuts, B.; Nijkamp, P. Tourist crowding perception and acceptability in cities: An applied modelling study on Bruges. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2133–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Hammitt, W. Backcountry encounter norms, actual reported encounters, and their relationship to wilderness solitude. J. Leis. Res. 1990, 22, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Budruk, M. The moderating effect of nationality on crowding perception, its antecedents, and coping behaviours: A study of an urban heritage site in Taiwan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1246–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leujak, W.; Ormond, R.F.G. Visitor perceptions and the shifting social carrying capacity of south Sinai’s coral reefs. Environ. Manag. 2007, 39, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, R.E. Crowding norms in backcountry settings: A review and synthesis. J. Leis. Res. 1985, 17, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.; Donnelly, M.; Petruzzi, J. Country of origin, encounter norms, and crowding in a frontcountry setting. Leis. Sci. 1996, 18, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Economic greenwash: On the absurdity of tourism and green growth. In Tourism in the Green Eeconomy; Reddy, V., Wilkes, K., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 339–358. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J.; Rogerson, C.M.; Hall, C.M. Geographies of tourism development and planning. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. ‘Destinations in change’: The transformation process of tourist destinations. Tour. Stud. 2004, 4, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J.M. Overtourism and tourismphobia: A journey through four decades of tourism development, planning and local concerns. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 353–357. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. UNWTO & WTM Ministers’ Summit 2017. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/archive/europe/unwto-wtm-ministers-summit-2017 (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Hammett, A.T. Importance-performance analysis (IPA) of sustainable tourism initiatives: The resident perspective. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Rathouse, K.; Scarles, C.; Holmes, K.; Tribe, J. Public understanding of sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K.; Johnson, R. Modelling resident attitudes towards tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio, J.C.; Andriotis, K. Social representations and community attitudes towards spring breakers. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. Why a theory of social representations? In Representations of the Social; Deaux, K., Philogéne, G., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 8–35. [Google Scholar]

- Doise, W.; Clémence, A.; Lorenzi-Cioldi, F. The Quantitative Analysis of Social Representations; Harvester Wheatsheaf: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M. Contested development paths and rural communities: Sustainable energy or sustainable tourism in Iceland? Sustainability 2019, 11, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castree, N. Nature; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Norkunas, M.K. The Politics of Public Memory: Tourism, History, and Ethnicity in Monterey, California; SUNY Press: Syracuse, Italy; New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, A. Up and down with ecology: The “issue–attention cycle”. Public Interest 1972, 28, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, F.; Scherr, S. Investigating an Issue–Attention–Action Cycle: A Case Study on the Chronology of Media Attention, Public Attention, and Actual Vaccination Behavior during the 2019 Measles Outbreak in Austria. J. Health Commun. 2019, 24, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Lindquist, E.; Vedlitz, A. Explaining media and congressional attention to global climate change, 1969–2005: An empirical test of agenda-setting theory. Political Res. Q. 2011, 64, 405–419. [Google Scholar]

- Lörcher, I.; Neverla, I. The dynamics of issue attention in online communication on climate change. Media Commun. 2015, 3, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Media attention and the market for ‘green’consumer products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonald, S. Changing climate, changing minds: Applying the literature on media effects, public opinion, and the issue-attention cycle to increase public understanding of climate change. Int. J. Sustain. Commun. 2009, 4, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Newig, J. Public attention, political action: The example of environmental regulation. Ration. Soc. 2004, 16, 149–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, L. Analysis of news coverage of haze in China in the context of sustainable development: The case of China daily. Sustainability 2020, 12, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schulte-Römer, N.; Söding, M. Routine reporting of environmental risk: The first traces of micropollutants in the German press. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 1108–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, L. Reconsidering global mobility–distancing from mass cruise tourism in the aftermath of COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay-Huet, S. COVID-19 leads to a new context for the “right to tourism”: A reset of tourists’ perspectives on space appropriation is needed. Tour. Geogr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L.; Moscardo, G.; Ross, G.F. Tourism Community Relationships; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jóhannesson, G.T.; Huijbens, E.H.; Sharpley, R. Icelandic Tourism: Past Directions—Future Challenges. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 278–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóhannesson, G.T.; Huijbens, E.H. Tourism in times of crisis: Exploring the discourse of tourism development in Iceland. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Alana, L.A.; Huijbens, E.H. Tourism in Iceland: Persistance and seasonality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benediktsson, K.; Lund, K.A.; Huijbens, E.H. Inspired by eruptions? Eyjafjallajökull and Icelandic tourism. Mobilities 2011, 6, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Iceland Business Sectors. Tourism. Accommodation. All Accommodation Establishments. Overnight Stays and Arrivals in all Types of Registered Accommodation 1998–2019. Available online: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Atvinnuvegir/Atvinnuvegir__ferdathjonusta__gisting__3_allartegundirgististada/SAM01601.px (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Statistics Iceland Business Sectors. Tourism. Accommodation. Hotels and Guesthouses. Occupancy Rate of Rooms and Beds in Hotels 2000-. Available online: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Atvinnuvegir/Atvinnuvegir__ferdathjonusta__gisting__1_hotelgistiheimili/SAM01104.px (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Icelandic Tourist Board. Tourism in Iceland in Figures—January 2020; Icelandic Tourist Board: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Wendt, M. From Boiling to Frozen? The Rise and Fall of International Tourism to Iceland in the Era of Overtourism. Environments 2020, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icelandic Tourist Board. Tourism in Iceland in Figures—2018; Icelandic Tourist Board: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Iceland Business Sectors. Tourism. Tourism Satellite Accounts. Main Aggregated Results, 2009–2017. Available online: https://statice.is/statistics/business-sectors/tourism/tourism-satellite-accounts/ (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Market and Media Research. Jákvæðni Gagnvart Erlendum Ferðamönnum Eykst (An Increase in Positive Attitudes towards International Tourists). Available online: https://mmr.is/frettir/birtar-nieurstoeeur/703 (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Bjarnadóttir, E.J.; Arnalds, Á.A.; Víkingsdóttir, A.S. Því Meiri Samskipti—Því Meiri Jákvæðni. Viðhorf Íslendinga til Ferðamanna og Ferðaþjónustu 2017 (The More Communication—The More Positivity. Icelanders’ Attitudes towards Tourists and the Tourism Industry 2017); Icelandic Tourism Research Center: Akureyri, Iceland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Social Science Research Institute. Viðhorf Íslendinga til Ferðaþjónustu. Unnið Fyrir Ferðamálastofu. (Icelander’s Attitudes towards the Tourism Industry. Conducted for the Icelandic Tourist Board); Social Science Research Institute: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadóttir, E.J.; Jóhannesson, A.Þ.; Gunnarsdóttir, G.Þ. Greining á Áhrifum Ferðaþjónustu og Ferðamennsku í Einstökum Samfélögum: Höfn, Mývatnssveit og Siglufjörður (An Analysis of the Impacts of the tourism Industry and Tourism on Selected Communities: Höfn, Mývatnssveit and Siglufjörður); Icelandic Tourism Resarch Center: Akureyri, Iceland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Runnstrom, M. Impact of Recreational Trampling in Iceland: A Pilot Study Based on Experimental Plots from Þingvellir National Park and Fjallabak Nature Reserve; Icelandic Tourist Board: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Icelandic Tourist Board. Ferðamálastofa—Icelandic Tourist Board: International Visitors in Iceland: Summer 2016. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Frettamyndir/2017/januar/sunarkonnun/sumar-2016-islensk.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Icelandic Tourist Board. Ferðamálastofa—Icelandic Tourist Board: International Visitors in Iceland: Winter 2015–2016. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/research/files/2016-09-13_ferdamalastofa_vetur_maskinuskyrslapdf (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Managing popularity: Changes in tourist attitudes to a wilderness destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 7, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M. Visitor satisfaction in wilderness in times of overtourism: A longitudinal study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, R.D.; Dominick, J.R. Mass Media Resarch—An Introduction, 9th ed.; Wadsworth: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger, F.N. Foundations of Behavioral Research, 4th ed.; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, E. A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. J. Methods Meas. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krippendorf, K. Reliability in content analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, C. Barcelona and Spain and Their Battle with Over-Tourism. Euromonitor International. 12 February 2018. Available online: https://blog.euromonitor.com/barcelona-overtourism/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Fes, N. Fight Over-Tourism and Travel off the Season. TourismReview News. 30 July 2018. Available online: https://www.tourism-review.com/fight-over-tourism-by-going-to-the-unknown-news10696 (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Stone, R. What a Month of Bicycle Rides Through Valencia Reveals about Authenticity in Tourism. Skift. 11 July 2018. Available online: https://skift.com/2018/07/11/what-a-month-of-bicycle-rides-through-valencia-reveals-about-authenticity-in-tourism/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Paul, K. Iceland is Hot, the U.S. is Not and Other Travel Trends for 2018. MarketWatch. 9 January 2018. Available online: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/here-is-where-everyone-is-going-to-be-booking-trips-to-in-2018-2018-01-05 (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Kay, J. What You Can Do about Overtourism. The New Daily. 3 August 2018. Available online: https://thenewdaily.com.au/life/travel/2018/08/03/overtourism/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Smith, O. Hotspots—Where to Next for Future Tourism Destinations? The New Zealand Herald. 27 September 2018. Available online: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/travel/news/article.cfm?c_id=7&objectid=12129989 (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Saarinen, J. Making wilderness: Tourism and the history of the wilderness idea in Iceland. Polar Geogr. 2011, 34, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Kirilenko, A.P. Climate Change and Tourism in English-Language Newspaper Publications. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, V.; Steen, A. Victims, hooligans and cash-cows: Media representations of the international backpacker in Australia. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M. Overtouristified cities: An online news media narrative analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1805–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, M.; Moraes, M.; Breda, Z.; Guizi, A.; Costa, C. Overtourism and tourismphobia: A systematic literature review. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2020, 68, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efla. Jafnvægisás Ferðamála [Balance-Axis for Tourism]; Efla, Icelandic Ministry of Industries and Innovation and Tourism Task Force: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Environment Agency of Iceland. Ástandsmat Áfangastaða Innan Friðlýstra Svæða (Status Evaluation on Tourist Destinations in Protected Areas). Available online: https://www.ust.is/library/Skrar/utgefid-efni/astand-fridlystra-svaeda/%C3%81standsmat%20fer%C3%B0amannasta%C3%B0a%20innan%20fri%C3%B0l%C3%Bdstra%20sv%C3%A6%C3%B0a-2018.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Daðason, K.T. Stóð Yfir Ferðamanni á Meðan Hann Kúkaði í Garð á Laugarvatni (Watched a Tourist While He Deficated in a Garden at Laugarvatn). Vísir. 3 September 2018. Available online: https://www.visir.is/g/2018708430d (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Ingólfsson, B.B. Klósettpappír Fýkur út um Allt (Toilet Paper Blowing Everywhere). Ruv.is. 11 July 2015. Available online: https://www.ruv.is/frett/klosettpappir-fykur-ut-um-allt (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Cheng, M.; Edwards, D. Social media in tourism: A visual analytic approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Dwyer, T. Sharing News Online: Commendary Cultures and Social Media News Ecologies; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, L. Hanoi’s ‘Train Street’ Becomes Selfie Central. CNN. 21 November 2018. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/hanoi-train-street-selfies/index.html (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- AFP. Overtourism and the Big Chill: Travel Trends in 2018. Breitbart. 7 March 2018. Available online: https://www.breitbart.com/news/overtourism-and-the-big-chill-travel-trends-in-2018/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Lagrave, K. Iceland is Not Overrun with Tourists, Despite What Everyone Says. Cntraveler. 25 October 2018. Available online: https://www.cntraveler.com/story/iceland-is-not-overrun-with-tourists-despite-what-everyone-says (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Do, E.M. How Instagram has Transformed How People Choose Their Next Vacation Destination. Global News. 25 November 2018. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/4647838/how-instagram-changed-travel-industry-millenials/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Sumers, B. Why Norwegian Air Doesn’t Worry about Overtourism When It Chooses New Routes. Skift. 19 July 2018. Available online: https://skift.com/2018/07/19/why-norwegian-air-doesnt-worry-about-overtourism-when-it-chooses-new-routes/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Landsbankinn. Fjárfesting í Ferðaþjónustu Síðustu ár Margföld á við Meðalár (Investments in the Tourism Industry Are Significantly Higher on Average). Hagfræðideild Landsbankans. 2018. Available online: https://umraedan.landsbankinn.is/umraedan/efnahagsmal/frett/2018/04/13/Hagsja-Fjarfesting-i-ferdathjonustu-sidustu-ar-margfold-a-vid-medalar/ (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Bogart, L. Commercial Culture: The Media System and the Public Interest; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ingólfsson, A.Þ. Grisjun Framundan í Ferðaþjónustunni. Mbl. 30 May 2018. Available online: https://www.mbl.is/frettir/innlent/2018/05/30/thetta_getur_ordid_sarsaukafullt/ (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Muhoho-Minni, P.; Lubbe, B.A. The role of the media in constructing a destination image: The Kenya experience. Communicatio 2017, 43, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, H., Jr. Agenda-setting with bi-weekly data on content of three national media. J. Q. 1989, 66, 942–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majin, G. A catastrophic media failure? Russiagate, Trump and the illusion of truth: The dangers of innuendo and narrative repetition. Journalism 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.; Price, E.A.; Yankey, N. Moral panic over youth violence: Wilding and the manufacture of menace in the media. Youth Soc. 2002, 34, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, M.T.; Boykoff, J.M. Climate change and journalistic norms: A case-study of US mass-media coverage. Geoforum 2007, 38, 1190–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Cannon, T.D.; Rand, D.G. Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2018, 147, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Framing tourism geography: Notes from the underground. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 601–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | Title of Article | Appeared On | Number of Reposts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. | Travel tips: Ten things you need to know about travel in 2018 | Traveller/The Age/Sydney Morning Herald/Canberra Times | 9 |

| 10 Trends That Will Make 2018 More Adventurous | Travel pulse (Canada) | 3 | |

| Iceland is hot, the U.S. is not—and other travel trends for 2018 | Market Watch | 5 | |

| 2018 Travel Hotlist: 20 hot trends and tickets for the year ahead | Independent (Ireland) | 2 | |

| Off-limits no more: Why you should visit these countries with a bad reputation | Traveller/The Age/Sydney Morning Herald/Canberra Times | 13 | |

| The best place to visit every month this year, according to a popular online travel agency | Business Insider | 1 | |

| Feb. | Barcelona and Spain and Their Battle With Over-Tourism//Smart Destinations to tackle overtourism | Euromonitor Internationally - Blog | 1 |

| European Travel Commission Reports Extraordinary Results for European Tourism in 2017 | European Travel Commission | 38 | |

| Mar. | Europe’s beauty spots plot escape from the too-many-tourists trap | The Guardian | 1 |

| Overtourism and the big chill: travel trends in 2018 | AFP/Breitbart/France24 | 33 | |

| Avoid the crowds: 7 popular destinations and the places to go instead | The National | 1 | |

| Breaking Travel News investigates: Tourism in Malta | Breaking Travel News | 3 | |

| Apr. | Dear dictionaries, this is why ‘overtourism’ should be your 2018 word of the year | The Telegraph | 5 |

| May | Venice Tourism Checkpoints are a sign of Europe’s fractures approach… | Skift | 1 |

| The 9 most at-risk tourist hotspots and where to go instead | Matador network | 1 | |

| Lonely Planet’s Top European Destinations Of 2018 Take Aim At Overtourism | Huffpost (Lonely Planet) | 7 | |

| Countries with the most tourists per head of population: Destinations suffering ‘overtourism’ | Traveller | 2 | |

| Reykjavik Rises, Barcelona Slips And Nice Rebounds As Top European Summer Travel Destinations In 2018 | Global Travel Media/Travel Weekly/PR Newswire | 17 | |

| Holidays 2018: Which country in the world has the biggest population of tourists? | Express | 1 | |

| June | Iceland to implement measures to curb over tourism | Travel and Tour World | 2 |

| Places to avoid and where you should go instead | News.com.au | 2 | |

| Video: Iceland Denies Overtourism as Europe Searches for Solutions | Skift | 2 | |

| GetYourGuide’s Branded Tours and 7 Other Tourism Trends This Week | Skift | 1 | |

| July | Increased Tourism: The Pressure of Unrestrained Growth | Hua Hin Today | 1 |

| Cities suffering from overtourism: How to visit as a responsible tourist | Traveller | 1 | |

| Avoid Crowds at Popular Destinations and Try These Hidden Gems | The National Geographic | 2 | |

| Why Norwegian Air Doesn’t Worry About Overtourism When It Chooses New Routes | Skift | 1 | |

| Europe Made Billions from Tourists. Now It’s Turning Them Away | For immediate release | 3 | |

| EIC lays out tourist roadmap—Measures to control overcrowding could improve the visitor experience | Bangkok Post | 2 | |

| Skift Basics: 10 Essential Reads to Understand Global Travel | Skift | 1 | |

| Aug. | Wish you weren’t here: how the tourist boom—and selfies—are threatening Britain’s beauty spots | The Guardian | 6 |

| From “Game of Thrones” to “Mamma Mia,” set-jetting tourism is everywhere | Quartz | 2 | |

| The other TV and film locations struggling like Cornwall with the Poldark effect | Cornwall Live | 14 | |

| Sept. | Overtourism: How you can help solve this worldwide problem. | Nomadic Matt’s Travel Site | 3 |

| Hotels springing up in New Zealand to close room shortage | Travel Weekly | 2 | |

| Experts to Discuss Overtourism in Nation’s Capital | Travel Pulse | 3 | |

| Overtourism—The Herman Trend Alert | Expert Click | 1 | |

| ‘Game Of Thrones’ Tourism Is Overwhelming This Idyllic Croatian Town | Uproxx | 2 | |

| Europe’s fastest growing tourist economies include Moldova, Bosnia, and… | Quartz | 1 | |

| Hotspots - Where to next for future tourism destinations? | New Zealand Herald | 2 | |

| The View From Europe: Who owns Tourism? | Carribean News/Barbados Advocate | 11 | |

| Oct. | Can the world be saved from overtourism? | CNN | 28 |

| Nature Works: New Research Shows The Economic Value Of National Parks | The Reykjavík Grape Wine | 1 | |

| Iceland visits to learn tourism lessons from New Zealand | Radio New Zealand | 1 | |

| The European Island Paradise That American Tourists Have Yet to Discover | Press from | 2 | |

| Ethical tourism: Steps to cut the negative effects of travel | The West Australian | 2 | |

| Overtourism: Time for some limits | The Garden Island | 1 | |

| How the Azores Will Hold Off the Crowds and Stay a Natural Wonder | Conde Nast Traveler | 1 | |

| Iceland Is Not Overrun With Tourists, Despite What Everyone Says | Conde Nast Traveler | 5 | |

| The Backlash againt overtourism | The Economist | 2 | |

| Nov. | WOW! Icelandair buys a competitor | Houston Chronicle/The Telegraph | 5 |

| Detouring: Top world destinations are overrun. Take these suggestions for… | The Gazette/The Washington Post | 24 | |

| Overbooked and overlooked—travel destinations to visit in 2019 | IOL News/Safrica24 | 2 | |

| Hanoi’s ‘train street’ becomes selfie central | CNN | 26 | |

| How Instagram has transformed how people choose their next vacation destination | The Leader News/Global News | 21 | |

| Dec. | More people will be visiting Portugal in 2019—here’s why | Conde Nast Traveller | 1 |

| Hidden Iceland: Avoiding the Crowds | Forbes | 1 | |

| Most popular destinations for Australians in 2018: Top 10 places on Traveller | Traveller | 1 | |

| Big Sur plea: Tourists, honor our home—Overwhelmed by crowds, locals launch ‘Big Sur Pledge” campaign for better behavior | The Mercury News | 4 | |

| TOTAL | - | 337 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Wendt, M. Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or Reality? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187375

Sæþórsdóttir AD, Hall CM, Wendt M. Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or Reality? Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187375

Chicago/Turabian StyleSæþórsdóttir, Anna Dóra, C. Michael Hall, and Margrét Wendt. 2020. "Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or Reality?" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187375

APA StyleSæþórsdóttir, A. D., Hall, C. M., & Wendt, M. (2020). Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or Reality? Sustainability, 12(18), 7375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187375