Environmental Education to Change the Consumption Model and Curb Climate Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Do the activities proposed in the environmental education program improve participants’ learning about the environmental impact of our consumption model and waste generation on climate change mitigation?

- Do the participants analyze the reality of the current model of consumption, evaluating more sustainable, fair, and supportive alternatives, in relation to the consumerist way of life?

- Do participants identify that consumption habits, such as shopping, types of food, transport, or energy saving, influence the emission of greenhouse gases and are part of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies?

- Do the activities developed in the environmental education program promote a critical and reflective attitude towards environmental problems (waste generation, depletion of natural resources, loss of biodiversity, etc.) caused by the adoption of unsustainable consumption habits?

- Are participants in the environmental education program aware of good practices for responsible consumption to reduce environmental pollution and the effects of climate change?

- Can the educational level and gender of the participants, separately or interacting, influence what is learned from the environmental education program?

2. Objectives

- To understand the previous knowledge that students of compulsory education have about climate change in different contexts and learning situations (school, extracurricular activities, and own home);

- To identify the level of information and training on the severity of climate change that students possess;

- To assess the degree of reflection of students on the impact of domestic consumption habits on climate change;

- To obtain the level of perception that students have in relation to the existence of solutions to the problems of climate change;

- To analyze the extent to which students associate the impact of everyday actions with the effects of climate change (switching off lights, unplugging appliances, using reusable bags, taking public transport, using renewable energy, etc.);

- To determine the influence that the educational level and gender may have on knowledge and behavior change for curbing climate change; and

- To obtain the scope and variety of what students in compulsory education learn from their own opinions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Analysis Procedure

- Dimension 1: Level of prior knowledge about climate change in different learning contexts and situations (school, out-of-school activities, and home)

- Dimension 2: Level of information on the severity of climate change

- Dimension 3: Level of perception about the impact of domestic consumption habits on climate change

- Dimension 4: Level of response to climate change issues

- Dimension 5: Level of contribution of everyday actions to climate change mitigation and adaptation (turning off lights, unplugging appliances, using reusable bags, taking public transport, using renewable energy, etc.)

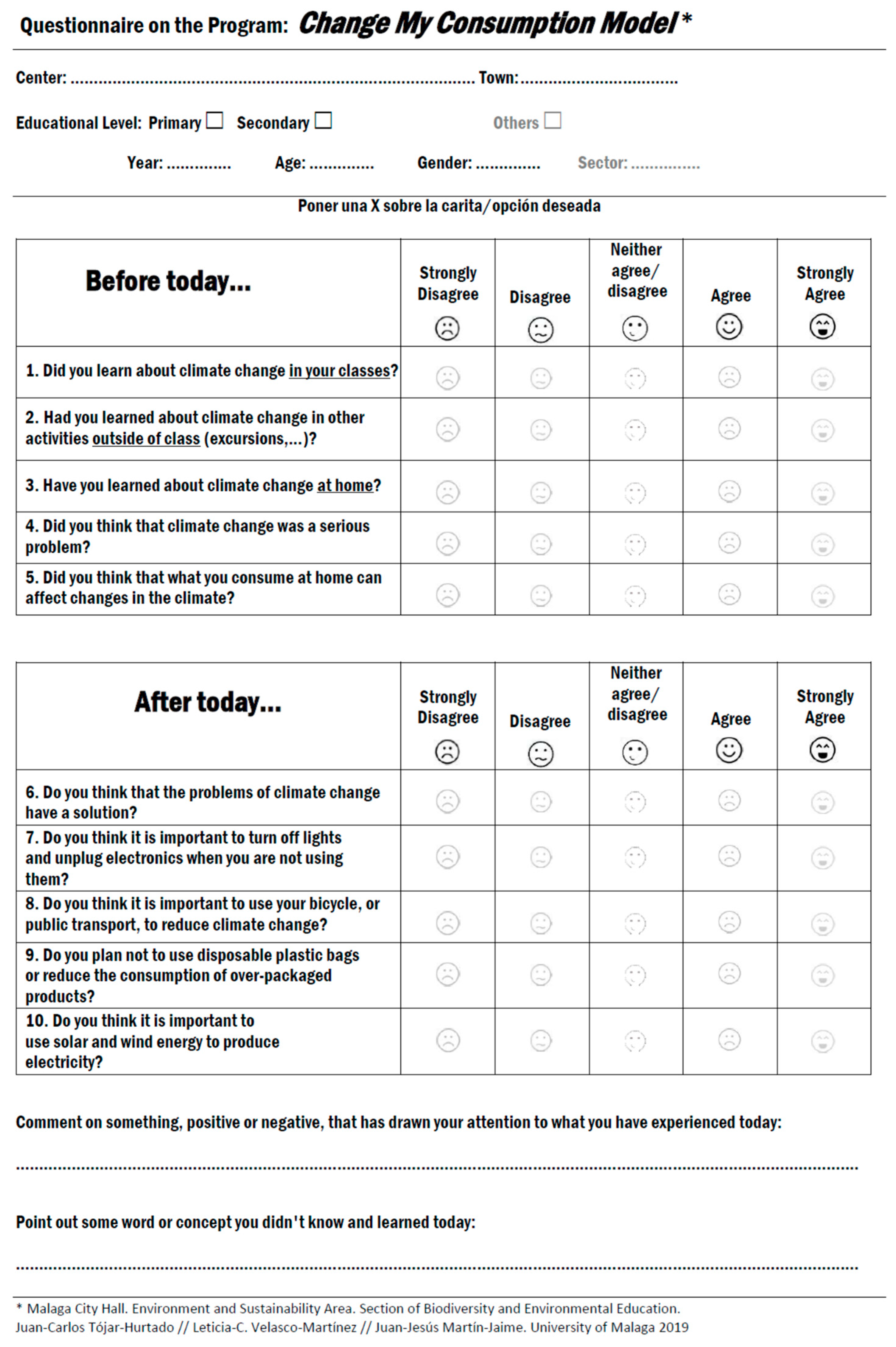

- Identification data (center, educational level, age, and gender)

- Ten close-ended questions, including five questions belonging to dimensions 1, 2, and 3 to be answered before applying the program, and five questions referring to dimensions 4 and 5 to be answered after applying the program

- Two open-ended questions: the first one to express positive and negative aspects of the program’s activities, and the second one to indicate knowledge or experiences acquired during the program

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.2. Multivariate Analysis

4.3. Open-Ended Questions Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Krasny, M.E.; DuBois, B. Climate adaptation education: Embracing reality or abandoning environmental values. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). IPCC Special Report on 1.5 C Headline Statements; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_headline_statements.pdf/ (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Sánchez-Mojica, B.E. La Migración en el Contexto de Cambio Climático y Desastres: Reflexiones para la Cooperación Española; Instituto de Estudios sobre Conflictos y Acción Humanitaria (IECAH): Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FACUA. Yo También Consumo de Forma Responsable; Facua Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Educación, Derechos de Infancia y Cambio Climático; UNICEF Comité Español: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría Confederal de Medio Ambiente y Movilidad de Comisiones Obreras. Evolución de las Emisiones de Gases de Efecto Invernadero en España (1990-2017); Confederación Sindical de Comisiones Obreras: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rousell, D.; Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A. A systematic review of climate change education: Giving children and young people a ‘voice’ and a ‘hand’ in redressing climate change. Children′s Geogr. 2020, 18, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Song, Y. Government Response to Climate Change in China: A Study of Provincial and Municipal Plans. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 1679–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, M.C.; Plate, R.E.; Oxarart, A.; Bowers, A.; Chaves, W.A. Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 791–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN (United Nations). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. A/RES/70/1. UN General Assembly; Seventieth Session. Agenda items 15 and 116; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, M.; Korhonen, J. Ninth graders and climate change: Attitudes towards consequences, views on mitigation, and predictors of willingness to act. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2017, 26, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Ioannou, H. Integrating Sustainable Consumption into Environmental Education: A Case Study on Environmental Representations, Decision Making and Intention to Act. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Novo, M. Educación ambiental y transición ecológica. Rev. Ambient. 2018, 125, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, A. Climate change education and research: Possibilities and potentials versus problems and perils? Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 6, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakellari, M.; Skanavis, C. Environmental Behavior and Gender: An Emerging Area of Concern for Environmental Education Research. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2013, 12, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The effect of gender on students’ sustainability consciousness: A nationwide Swedish study. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 48, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielraja, R. A Study of Environmental Awareness of Students at Higher Secondary Level. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 2019, 7, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saukani, N.; Ismail, N.A. Identifying the Components of Social Capital by Categorical Principal Component Analysis (CATPCA). Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 631–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Bala, K. Sampling and Sampling Methods. Biom. Biostat. Int. J. 2017, 5, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gozalbo, M.E.; Tójar-Hurtado, J.C. Identifying key issues for university practitioners of garden-based learning in Spain. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 51, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Landscape of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Modikela Nkoana, E. Exploring the effects of an environmental education course on the awareness and perceptions of climate change risks among seventh and eighth grade learners in South Africa. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2020, 29, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Essays on Climate Change Mitigation, Building Energy Efficiency, and Urban Form. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- García-Díaz, J.E. Los Problemas de la Educación Ambiental: ¿Es Posible una Educación Ambiental Integradora? Centro Nacional de Educación Ambiental: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jickling, B.; Sterling, S. Post-Sustainability and Environmental Education: Framing Issues. In Post-Sustainability and Environmental Education; Jickling, B., Sterling, S., Eds.; Palgrave Studies in Education and the Environment; Palgrave Macmillan Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesa-Alosno, M.G. Comunicación y Representaciones del Cambio Climático: El Discurso Televisivo y el Imaginario de los Jóvenes Españoles. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, España, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Items | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Did you learn about climate change in your classes? | 3.19 | 1.05 |

| Had you learned about climate change in other activities outside of class (excursions)? | 2.81 | 1.12 |

| Have you learned about climate change at home? | 2.78 | 1.17 |

| Did you think that climate change was a serious problem? | 3.72 | 1.30 |

| Did you think that what you consume at home can affect changes in the climate? | 3.30 | 1.26 |

| Do you think that the problems of climate change have a solution? | 3.98 | 0.98 |

| Do you think it is important to turn off lights and unplug electronics when you are not using them? | 4.47 | 0.88 |

| Do you think it is important to use your bicycle, or public transport, to reduce climate change? | 4.37 | 0.85 |

| Do you plan not to use disposable plastic bags or reduce the consumption of over-packaged products? | 3.88 | 1.10 |

| Do you think it is important to use solar and wind energy to produce electricity? | 4.36 | 0.89 |

| Effect | Contrast | Value | F | Hp df | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interception | Pillai’s trace | 0.981 | 3024.51 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| Wilks’ lambda | 0.019 | 3024.51 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.98 | |

| Hotelling’s trace | 50.662 | 3024.51 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.98 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | 50.662 | 3024.51 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.98 | |

| Gender | Pillai’s trace | 1.26 | 1.27 | 10 | 0.24 | 0.02 |

| Wilks’ lambda | 0.98 | 1.27 | 10 | 0.24 | 0.02 | |

| Hotelling’s trace | 0.88 | 1.27 | 10 | 0.24 | 0.02 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | 0.85 | 1.27 | 10 | 0.24 | 0.02 | |

| Educational level | Pillai’s trace | 1.26 | 13.65 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.19 |

| Wilks’ lambda | 0.98 | 13.65 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.19 | |

| Hotelling’s trace | 0.88 | 13.65 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.19 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | 0.85 | 13.65 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.19 | |

| Gender X Educational level | Pillai’s trace | 1.26 | 0.55 | 10 | 0.85 | 0.01 |

| Wilks’ lambda | 0.98 | 0.55 | 10 | 0.85 | 0.01 | |

| Hotelling’s trace | 0.88 | 0.55 | 10 | 0.85 | 0.01 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | 0.85 | 0.55 | 10 | 0.85 | 0.01 |

| Effect | Items | F | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Did you think that what you consume at home can affect changes in the climate? | 4.94 | 0.027 | 0.08 |

| Educational level | Did you learn about climate change in your classes? | 7.91 | 0.005 | 0.01 |

| Had you learned about climate change in other activities outside of class (excursions)? | 19.69 | 0.000 | 0.03 | |

| Have you learned about climate change at home? | 11.46 | 0.001 | 0.02 | |

| Did you think that climate change was a serious problem? | 92.14 | 0.000 | 0.13 | |

| Did you think that what you consume at home can affect changes in the climate? | 5.65 | 0.018 | 0.01 | |

| Do you plan not to use disposable plastic bags or reduce the consumption of over-packaged products? | 21.48 | 0.000 | 0.03 | |

| Do you think it is important to use solar and wind energy to produce electricity? | 4.17 | 0.041 | 0.01 |

| Macro-category 1 | Learning |

| Category 1.1: | Learning about flora |

| Sub-categories | Name of the plants in the area |

| Basic knowledge of the plants in the area | |

| Importance and role of plants in the natural environment | |

| Recommendations for their care, protection, and respect | |

| Variety of plants in the area (basil, carob, asparagus, …) | |

| Types of plants: | |

| Micro-categories | Medicinal plants Endangered plants Toxic plants Prehistoric plants |

| Category 1.2: | Learning about wildlife: |

| Sub-categories | Diversity of species (oil, cochineal, booted eagle, ...) |

| Need to preserve protected species (chameleon, ...) | |

| Detection of the presence of animals through their footprints and excrements | |

| Recommendations for their care, protection, and respect (do not throw stones at them) | |

| Curiosities (e.g., lipstick is made from the piglet) | |

| Desire to learn more about the fauna of the area | |

| Category 1.3: | Learning about the physical environment |

| Sub-categories | Names of the natural area (nature, countryside, environment, landscape, park...) |

| Knowledge about elements of the natural space (viewpoints, paths, bushes, rocks, sandstone, ...) | |

| Category 1.4: | Consumer learning |

| Sub-categories | Concept of consumption |

| Current consumption model | |

| Importance of changing the consumption model | |

| Excessive consumption (plastic, energy...) | |

| Implications of reducing energy consumption | |

| Knowledge about renewable energy (photovoltaic panels) | |

| Category 1.5: | Learning about recycling: |

| Sub-categories | Knowledge about objects that can be recycled (can everything be recycled?) |

| Need to reduce and reuse plastics (e.g., from garbage you can make clothes) | |

| Satisfaction in knowing that others recycle | |

| Awareness of the excessive use of plastics | |

| Relationship between recycling and care of the environment (e.g., with paper the felling of trees is reduced...) | |

| Category 1.6: | Learning about climate change |

| Sub-categories | Evidence on climate (temperature increases) |

| Importance of raising awareness about climate change | |

| Category 1.7: | Learning about waste generation |

| Sub-categories | Origin and knowledge of the composition of artificial mountains |

| Impacts of artificial mountains on the environment and health (environmental deterioration, dirt, odors, diseases...) | |

| Interesting and creative solutions to generate less waste | |

| Awareness of the influence of human activity and behavior on the deterioration of the environment through the generation of waste | |

| Category 1.8: | Learning about values and attitudes: |

| Sub-categories | Care for the environment |

| Respect for Malaga’s natural heritage through knowledge | |

| Collaboration to care for the environment | |

| Awareness of the need to re-use natural elements | |

| Need to be green | |

| Macro-category 2 | Program feedback |

| Category 2.1: | Program design and development: |

| Sub-categories | Content of the interesting and formative activity |

| Adequate space (nice, clean, care ...) | |

| Monitors (trained, friendly, enjoyable, and didactic) | |

| Difficulties in walking the path (slippery ground, climbing hills, excessive walking, presence of sharp plants, insects, heat, bad smell, no litter bins...) | |

| Category 2.2: | Program results (learning and student satisfaction): |

| Sub-categories | Learning acquisition |

| Fun, enjoyment, and entertainment | |

| Good experience | |

| Possibility to share with friends |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velasco-Martínez, L.-C.; Martín-Jaime, J.-J.; Estrada-Vidal, L.-I.; Tójar-Hurtado, J.-C. Environmental Education to Change the Consumption Model and Curb Climate Change. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187475

Velasco-Martínez L-C, Martín-Jaime J-J, Estrada-Vidal L-I, Tójar-Hurtado J-C. Environmental Education to Change the Consumption Model and Curb Climate Change. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187475

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelasco-Martínez, Leticia-Concepción, Juan-Jesús Martín-Jaime, Ligia-Isabel Estrada-Vidal, and Juan-Carlos Tójar-Hurtado. 2020. "Environmental Education to Change the Consumption Model and Curb Climate Change" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187475

APA StyleVelasco-Martínez, L.-C., Martín-Jaime, J.-J., Estrada-Vidal, L.-I., & Tójar-Hurtado, J.-C. (2020). Environmental Education to Change the Consumption Model and Curb Climate Change. Sustainability, 12(18), 7475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187475