Abandoned Places and Urban Marginalized Sites in Lugoj Municipality, Three Decades after Romania’s State-Socialist Collapse

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Setting Theoretical Background on Urban Dereliction and Ruins

3. Data, Materials, and Methods

4. Results and Discussion—Urban Dereliction as Part of the Romanian Postsocialist Urban Formation

4.1. Ruins of Postsocialist Romanian Cities

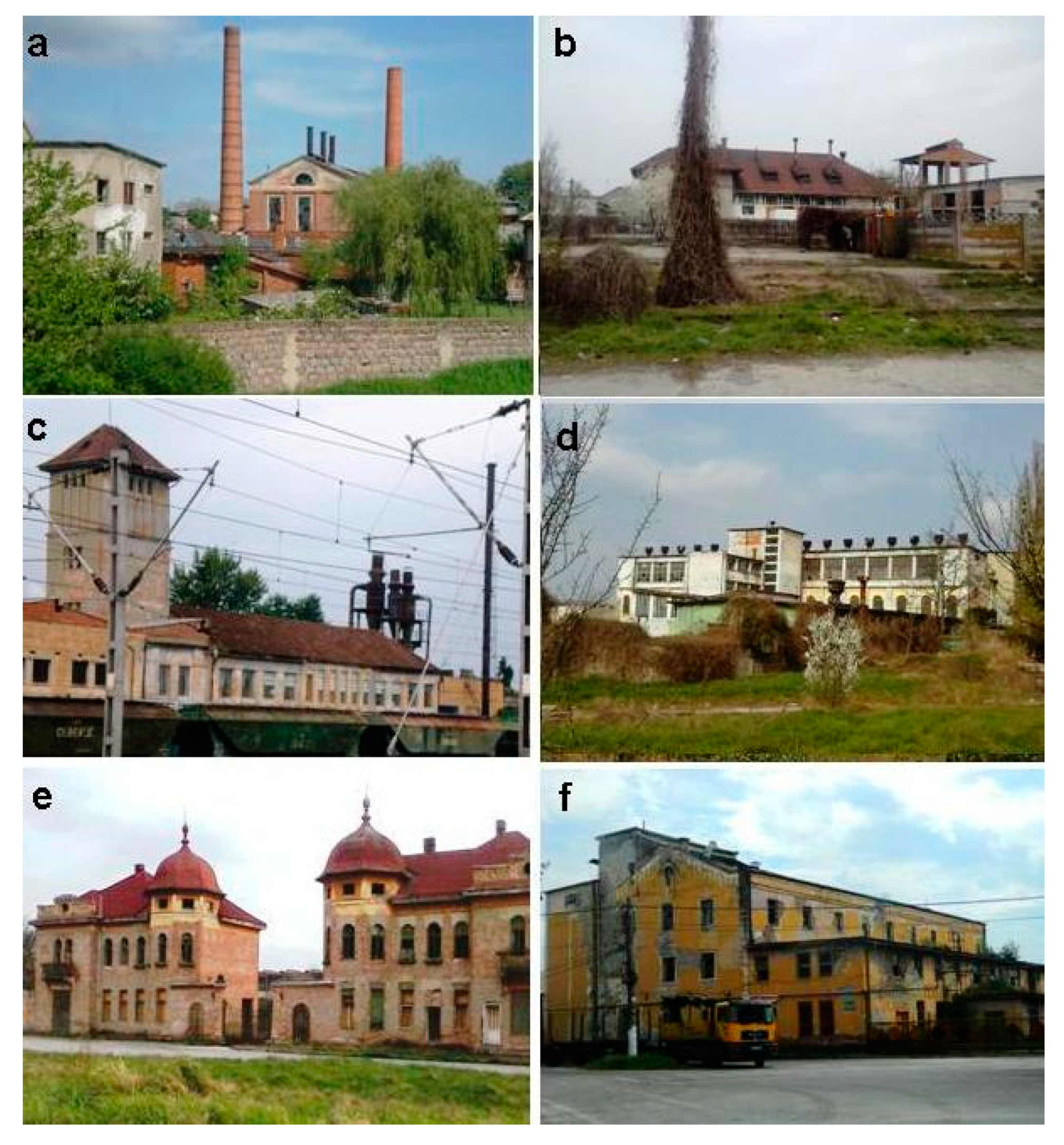

4.2. Investigating Local Urban Dereliction in the Romanian Small-Sized Towns: The Case of Lugoj Municipality

“Since the year of 1972, I have lived and worked here. The factory operated properly before and after 1990, but its survival chances are considered compared to the new national and international milk producers. It could function with a good management. I think its failure was deliberate. All equipment was removed. The scrap-selling center is just around the corner. Since the year 2000, the factory has turned to ruins as its neighboring rail area. This part of the town is desolate with repulsive landscapes. Looking around, we could find: ruins hosting waste, stray dogs, homelessness and high weeds, everywhere… Does someone in our government care about this ruined place? I don’t think so. Yet, these ruins are a part of our everyday life.”(Personal conversation: P.I./male/66.)

“In 1995, some Japanese investors intended to purchase and modernize the factory in order to continue the natural silk production, but the deal with Romanian authorities failed. Nobody knows the reason for this. Furthermore, a Romanian investor purchased it at a low price. It was then, divided; some parts were sold, put on let or turned to services. However, its most backward part is ruined.”(Interviewee/formerly engineer/L. D./62/female.)

“I remembered in the 90s, that the natural silk section has been dismantled. All the stainless steel equipment has been loaded into huge trucks. I think it was sold as scrap, making the new owners richer. Since I was 18 years old, my life has been connected to this plant. Then, I lost my job, as the town lost one of the most prominent factories. Sometimes, I still watch the ruins, regretting what was once there. As a dismissed worker after 25 years of work, my husband and I had to commute 60 km away, in Timişoara for new jobs, because at that time, no one hired us in Lugoj. We still regret the failure of the plant.”(Interviewee: I.J./female/62.)

“I used to manage this plant for twenty years. In the year 2002, based on a local government’s decision, it stopped operating like the others in town. They became redundant, since private heating systems were installed in blocks of flats. Being under local municipality administration, but at the same time, in the care of no one, soon its equipment disappeared. I am sure it was sold as scrap. The plant was further vandalized and became a ruin with a repulsive image, sheltering homeless, stray dogs and waste. With the plant closure, I lost my job just like my colleagues. I live opposite it, I saw it degrading every day, and I regret that the authorities did nothing with the ruins that harm the inner landscape of this neighborhood.”(Interviewee: M.N./male/65.)

“I see the ruin of this heating plant, every time I look through my window. Instead of seeing, an enjoyable landscape, I see this wasteland and repulsive place hosting stray dogs and homeless people fed and cared by different tenants. I am afraid of this place. In summer, the smell of the waste inside it is terrible, so I cannot even vent the house. If my living conditions were favorable, I would sell my current apartment and move elsewhere.”(Interviewee: K.B./male/44.)

“I do not understand why the local authorities do nothing with these ruins. The town needs social houses and these buildings remain vacant. Rather than hosting the homeless, they could turn to social housing, for poor families. Of course, these actions require important financial resources, but the local government has to take this issue seriously because there are many opportunities to apply for EU funding for local housing. I think there is too much ignorance, while viewing local dereliction.”(Interviewee: P.L/female/39.)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mah, A. Memory, uncertainty and industrial ruination: Walker riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mah, A. Industrial Ruination, Community and Place Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Turok, I. Redundant and marginalized spaces. In Cities and Economic Change; Paddison, R., Hutton, T., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2015; pp. 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne, M. Mayors and urban governance: Discursive power, identity and local politics. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2012, 13, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weck, S.; Lobato, I.R. Social exclusion: Continuities and discontinuities in explaining local patterns. Local Econ. 2015, 30, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSilvey, C.; Edensor, T. Reckoning with ruins. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 37, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanilov, K. (Ed.) The Post-Socialist City: Urban Form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Edensor, T. Industrial Ruins. Space, Aesthetics and Materiality; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Edensor, T. The ghosts of industrial ruins: Ordering and disordering memory in excessive space. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2005, 23, 829–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loures, L.; Panagopoulos, T. From derelict industrial areas towards multifunctional landscapes and urban renaissance. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2007, 3, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Loures, L.; Panagopoulos, T. Sustainable Reclamation of Industrial Areas in Urban Landscapes; Wit Press: Southampton, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. Introduction: Towards a political understanding of new ruins. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. Translating space: The politics of ruins, the remote and peripheral places. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strangleman, T.; Mah, A. Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; Volume 38, pp. 1126–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, K.A.; Stevens, Q. Tying down loose space. In Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ruibal, A. Time to destroy: An archaeology of supermodernity. Curr. Anthropol. 2008, 49, 247–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, S.A.; Stanilov, K. Twenty Years of Transition: The Evolution of Urban Planning in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, 1989–2009; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kideckel, D. Getting by Post-Socialist Romania: Labor, the Body and Working-Class Culture; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kovácz, Z.; Weissner, R.; Zischner, R. Urban renewal in the inner city of Budapest: Gentrification from a postsocialist perspective. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puşcă, A. Industrial and human ruins of postcommunist Europe. Space Cult. 2010, 13, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, A.; Timár, J. Uneven transformations: Space, economy and society 20 years after the collapse of state-socialism. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2010, 17, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L. New socio-spatial formations: Places of residential segregation and separation, Czechia. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2009, 100, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L. Post-socialist cities. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Stanilov, K.; Sýkora, L. Planning markets and patterns of residential growth in post-socialist metropolitan Prague. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2012, 29, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Kaczmarek, S. The socialist past and postsocialist urban identity in Central and Eastern Europe: The case of Łódź, Poland. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2008, 15, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefs, M. Unused urban space: Conservation or transformation? Polemics about the future of urban wastelands and abandoned buildings. City Time 2006, 2, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.C.; Barros, M.J. Local municipalities’ involvement in promoting the internationalisation of SMEs. Local Econ. 2014, 29, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Stenning, A.C. (Eds.) East Central Europe and the Former Soviet Union: The Post Socialist Economies; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dunford, M.; Smith, A. Catching up or falling behind? Economic performance and regional trajectories in the ‘New Europe’. Econ. Geogr. 2000, 76, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Young, C. Reconfiguring socialist urban landscapes: The’left-over’ of state-socialism in Bucharest. Hum. Geogr. J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 4, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marcińczak, S.; Sagan, I. The socio-spatial restructuring of Łódź, Poland. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 1789–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S. The evolution of spatial patterns of residential segregation in Central European Cities: The Łódź functional urban region from mature socialism to mature post-socialism. Cities 2012, 29, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Musterd, S.; Stepniak, M. Where the grass is greener: Social segregation in three major Polish cities at the beginning of the 21st Century. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2012, 19, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Gentile, M.; Rufat, S.; Chelcea, L. Urban geographies of hesitant transition: Tracing socioeconomic segregation in Post-Ceausescu Bucharest. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nădejde, Ş.; Pantea, D.; Dumitrache, A.; Braulete, I. Romania: Consequences of small steps policy. In Rise and Decline of Industry in Central and Eastern Europe. A Comparative Study of Cities and Regions in Eleven Countries; Muller, B., Finka, M., Lintz, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pickles, J. The spirit of post-socialism: Common spaces and the production of diversity. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2010, 17, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenning, A. Placing (post-) socialism. The making and remaking of Nowa Huta, Poland. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2000, 7, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenning, A.; Smith, A.; Rochovská, A.; Swiatek, D. Domesticating Neoliberalism: Spaces of Economic Practice and Social Reproduction in Post-Socialist Cities; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chelcea, L. Bucureştiul Postindustrial, Memorie, Dezindustrializare şi Regenerare Urbană; Polirom: Bucharest, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Iancu, S. Ruine Industriale ale Epocii de Aur (industrial ruins of the golden age). România Liberă. 28 May 2007. Available online: http://www.romanialibera.ro/actualitate/fapt-divers/ruine-industriale-epocii-de-aur-96496 (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Ivanov, C. Cum pot fi Transformate Ruinele Industriale în Minuni Arhitecturale (How Industrial Ruins Could Turn to Architecture Wonderlands). 29 November 2010. HotNews.ro. Available online: http://economie.hotnews.ro/stiri-imobiliar-8079922-cum-pot-transformate-ruinele-industriale-bijuterii-arhitectonice.htm (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Kiss, E. Restructuring in the industrial areas of Budapest in the period of transition. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, E. Spatial impacts of post-socialist industrial transformation in the major Hungarian cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2004, 11, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, E. The evolution of industrial areas in Budapest after 1989. In The Post-Socialist City: Urban Form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Stanilov, K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The state and society. In State, Space, World: Selected Essays by Henri Lefebvre; Brenner, N., Elden, S., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009; pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chelcea, L. The ‘Housing Question’ and the state-socialist answer: City, class and state remaking in 1950s Bucharest. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, J.D. Rescuing critique: On the ghetto photography of Camilo Vergara. Theory. Cult. Soc. 2008, 25, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickiewicz, T.; Zalewska, A. Deindustrialization. Lessons from the Structural Outcomes of Post-Communist Transition; Working Paper 463; William Davidson Institute: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, J. Neoliberalising a divided society? The regeneration of Crumlin Road Gaoland and Girdwood Park, North Belfast. Local Econ. 2014, 29, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.; Mitchell, D. Neoliberal landscapes of deception: Detroit, Ford Field and the Ford Motor Company. Urban Geogr. 2004, 25, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubchikov, O.; Badyina, A.; Makhrova, A. The hybrid spatialities of transition: Capitalism, legacy and uneven urban economic restructuring. Urban Stud. 2013, 51, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. The political economy of urban ruins: Redeveloping Shanghai. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesley, C. Globalization and corruption in post-Soviet countries: Perverse effects of economic openness. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2015, 56, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. Cultural Geography: A Critical Introduction; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- NIS. National Institute of Statistics of Romania, Bucharest. 2015. Online Database TempoOnline. Available online: www.tempoonline.ro (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Jucu, I.S. Romanian post-socialist industrial restructuring at the local scale: Evidence of simultaneous processes of de-/reindustrialization in the lugoj municipality of Romania. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2015, 17, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucu, I.S. Lugoj the municipality of seven women to a man. From myth to post socialist reality. An. Univ. Vest Timis. Ser. Geogr. 2009, 19, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schönle, A. Ruins and history: Observations on Russian approaches to destruction and decay. Slav. Rev. 2006, 65, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoler, A.L. Imperial debris: Reflections on ruins and ruination. Cult. Anthropol. 2008, 23, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto, M.; Brito, M. Aparecida de. os Vazios Urbanos e o Processo de Redefinição Socioespacial em Dourados. (Assessing Urban Processes of Spatial Redefining); MS. UFMS: Campo Grande, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Millington, N. Post-industrial imaginaries: Nature, representation and ruin in Detroit, Michigan. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, S.; Jucu, I.S. Producing urban industrial derelict places: The Case of the Solventul petrochemical plant in Timişoara. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers-Hall, H. The concept of ruin: Sartre and the existential city. Urbis Res. Forum 2009, 1, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Theodore, N.; Peck, J. Framing neoliberal urbanism: Translating ‘Commonsense’ urban policy across the OECD Zone. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2011, 19, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Theodore, N. Neoliberalism and the Urban Condition. City 2005, 9, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zanocea, C. Singur pe Ruinele Industriei Comuniste. (Alone on the Communist Ruins). 4 February 2014. Ziarul de Roman. Available online: http://www.ziarulderoman.ro/singur-pe-ruinele-industriei-comuniste/ (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Boym, S. Ruins of the avant-garde: From Tatlin’s tower to paper architecture. In Ruins of Modernity; Hell, J., Schönle, A., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010; pp. 58–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tonnelat, S. ‘Out of frame’: The (in) visible life of urban interstice. Ethnography 2008, 9, 291–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J. Everyday afterlife: Walter Benjamin and the politics of abandonment in Saskatchewan, Canada. Cult. Stud. 2011, 25, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, G. The dead zone and the architecture of transgression city: Analysis of urban trends. City 2000, 4, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H. Exploring the creative possibilities of awkward space in the city. J. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A.; Tylecote, M. Ambivalent landscapes—wilderness in the urban interstices. Landsc. Res. 2007, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America; Architectural Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bagaeen, S. Redeveloping former military sites: Competitiveness, urban sustainability and public participation. Cities 2006, 23, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barndt, K. Memory Traces of an Abandoned set of Futures Dustrial Ruins in the Post-Industrial landscapes of East and West Germany. In Ruins of Modernity; Hell, J., Schönle, A., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2007; pp. 270–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hell, J.; Schönle, A. (Eds.) Ruins of Modernity; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lahusen, T. Decay or endurance? The ruins of socialism. Slav. Rev. 2006, 65, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiaanse, K. The City as a Loft; Berlin: Top 38; ETH Zurich: Berlin, Germany.

- Loures, L.; Horta, D.; Panagopoulos, T. Strategies to reclaim derelict industrial areas. WSEAS Environ. Dev. 2006, 5, 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Unt, A.L.; Travlou, P.; Bell, S. Blank space: Exploring the sublime qualities of urban wilderness at the former fishing harbor in Tallinn, Estonia. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. Military landscapes and secret science: The case of Orford Ness. Cult. Geogr. 2008, 15, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, P.; Roberts, M.S. Edgelands: Journeys into England’s True Wilderness; Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, B. Infrastructure and indeterminacy: The production of residual space. In Proceedings of the CRESC Conference ‘Framing the City’, Manchester, UK, 6–9 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qviström, M. Network ruins and green structure development: An attempt to trace relational spaces of a railway ruin. Landsc. Res. 2012, 37, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadolu, B.; Lucheş, D.; Dincă, M. The patterns of depopulation in Timişoara—Research note. Sociol. Românescă SR 2011, 9, 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nadolu, B.; Dincă, M.; Lucheş, D. Urban Shrinkage in Timişoara, Romania; Research Report; West University of Timişoara: Timisoara, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, M.H. Media tools for urban design. In Companion to Urban Design; Banerjee, T., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, W.; Price, L. Local economic strategy development under Regional Development Agencies and Local Enterprise Partnership. Applying the lens of the multiple streams framework. Local Econ. 2013, 28, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernstein, S. Rising from the Ruins. The Aestheticization of Detroit’s Industrial Landscape; Lewis and Clark College: Portland, OR, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andreşoiu, B.; Bonciocat, Ş.; Ioan, A.; Oţoiu, N.A.; Chelcea, L.; Simion, G. Kombinat. Ruine Industriale ale Epocii de Aur; Igloo Patrimoniu: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P. Regional identities and regionalization in East Central Europe. Post Sov. Geogr. Econ. 2001, 42, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovici, N. Workers and the city: Rethinking the geographies of power in post-socialist urbanization. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 2377–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesalon, L.; Cretan, R. “Little Vienna” or “European avant-garde city”? Branding narratives in a Romanian City. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2019, 11, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cojocar, A.; Industria Trece Printr-un val de Inchideri care Afecteaza Cresterea Economica. Care sunt Cauzele Dezindustrializarii de dupa 89 si unde s-a gresit? Am Privatizat Destul sau Prea Putin? De ce nu am Atras Destui noi Investitori? Ziarul Financiar. 7 March 2013. Available online: https://www.zf.ro/analiza/industria-trece-printr-val-inchideri-afecteaza-cresterea-economica-cauzele-dezindustrializarii-dupa-89-unde-s-gresit-privatizat-destul-prea-putin-atras-destui-investitori-10648895 (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Creţan, R.; O’Brien, T. Corruption and conflagration: (in) justice and protest in Bucharest after the Colectiv fire. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, C.C. Ministerul Economiei Caută Potenţialul Nevalorificat Printre Ruinele Industriei, Ziarul Hunedoreanului. 2013. Available online: http://zhd.ro/ministerul-economiei-cauta-potentialul-nevalorificat-printre-ruinele-industriei (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- DIGI 24. Business Club. Industria Sticlei în România în ruine. Ultima Suflare a Sticlei de Pădurea Neagră. 2014. Available online: http://www.digi24.ro/Stiri/Digi24/Economie/Stiri/BUSINESS+CLUB+Industria+sticlei+din+Romania+in+ruine+Ultima+suflonline (accessed on 10 June 2016).

- Deșteptarea. Prin Ruinele Industriei Băcăuane. 2013. Available online: athttp://www.desteptarea.ro/prin-ruinele-industriei-bacauane/ (accessed on 10 June 2016).

- Kotz, D.M. Globalization and neoliberalism. Rethink. Marx. 2002, 14, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soederberg, S. The Politics of New Financial Architecture: Re-Imposing Neoliberal Domination in the Global South; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein, M.A. What happened in East European (political) economies?: A balance sheet for neoliberal reform. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2009, 23, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, J.; Smith, A. (Eds.) Theorising Transition: The Political Economy of Postcommunist Transformation; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Avram, C. În Premieră (In First Run). 2014. Available online: http://www.antena3.ro/romania/romania-otravita-ruinele-industriei-comuniste-ne-baga-in-pamant-cu-trei-ani-mai-devreme-230163.html (accessed on 10 June 2016).

- Dochia, A. Despre Soarta Tristă a Industriei Chimice Româneşti. Ziarul Financiar. 2012. Available online: http://www.zf.ro/opinii/despre-soarta-trista-a-industriei-chimice-romanesti (accessed on 21 October 2018).

- Ianoş, I. Dinamică Urbană; Tehnică: Bucharest, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ianoş, I.; Heller, W. Spaţiu, Economie şi Sisteme de Aşezări; Tehnică: Bucharest, Romania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jigoria, L.; Popa, N. Industrial brownfields: An unsolved problem in post-socialist cities. A comparison between two mono-industrial cities: Resita (Romania) and Pancevo (Serbia). Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 2719–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A. România te Iubesc. Available online: http://romaniateiubesc.stirileprotv.ro/stiri/romania-te-iubesc/romania-te-iubesc-industria-romaneasca-marire-si-decadere.html (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Savu, C. Cine a pus ARO pe butuci. In România te Iubesc; Herlo, P., Năstase, R., Dima, A., Savu, C., Angelescu, P., Eds.; Humanitas: Bucharest, Romania, 2018; pp. 210–229. [Google Scholar]

- Domanski, B. Industrial change and foreign direct investments in the post socialist economy: The case of Poland. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2003, 10, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafiuc, J. Platforma Iadului. Rulmentul Brasov pe Vremuri Mandria Socialismului a Devenit o ruină. 23. Libertatea, Iunie. 2019. Available online: https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/platforma-iadului-cum-arata-azi-rulmentul-brasov-mandria-socialismului-romanesc-2673705 (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Chowdhury, S.; Kain, J.H.; Adelfio, M.; Volkhko, Y.; Norrman, J. Greening the brown. A bio-based land-use framework for analyzing the potential of urban brownfields in an urban circular economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamju, M. Magneții s-au Întors pe Ruinele Fostelor Platforme Industrial. Actualitate. Mesagerul hunedorean, Hunedoara. 2013. Available online: https://www.mesagerulhunedorean.ro/magnetii-s-au-intors-pe-ruinele-fostelor-platforme-industriale (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- National Institute of Statistics Romania (NIS). Breviar Statistic al Municipiului Lugoj, 2009–2010; NIS: Timisoara, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jucu, I.S. Analiza Procesului de Restructurare Urbană în Municipiul Lugoj; Universităţii de Vest: Timisoara, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wẹc1awowicz, G. From egalitarian cities in theory to non-egalitarian cities in practice: The changing social and spatial patterns in Polish cities. In Of States and Cities: The Partitioning of Urban Space; Marcuse, P., van Kempen, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Egresi, I. Foreign direct investment in a recent entrant to the EU. The case of the automotive industry in Romania. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2007, 45, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariş, C. Unde e textila de altă dată? Actualitatea 2010, 708, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, D. În prag de sărbători locuitorii din Mondial se luptă cu frigul şi foamea (In winter the inhabitants of Mondial face with cold and hungry). Actualitatea 2013, 1176, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Niţoiu, C. Fabrica de lapte din Lugoj cumpărată de fiica fostului director CFR Timişoara. Redeşteptarea 2007, 1180, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gaidoş, C.O. Complexul industrial Abatorul şi Fabrica de gheaţă 1911–1912. Monitorul de Lugoj 2005, 77, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jucu, I.S.; Pavel, S. Post-communist urban ecologies of Romanian medium-sized towns. Forum Geogr. 2019, 18, 170–185. [Google Scholar]

- Dawidson, K.E. Redistribution of land in post-communist Romania. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2005, 46, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiv, N. Beating the Bounds: A Walking Exploration of the Capital Corridor Rail Line. 2011. Available online: http://beatingthebounds.typepad.com (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Hananel, R. Can centralization, decentralization and welfare go together?: The case of Massachusetts affordable housing policy (Ch. 40B). Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2487–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opris, P. Rachete Balistice Sovietice in Romania (1961–1998). 2018. Available online: https://www.contributors.ro/rachete-balistice-sovietice-in-romania-1961-1998-2/ (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Lugoj Tion. La Lugoj se Inființează un nou Cartier Militari. 22 June 2011. Available online: https://www.tion.ro/lugoj/la-lugoj-se-infiinteaza-un-nou-cartier-militari-342246/ (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Obeadă, C. Cele mai Multe clădiri Emblem ale Lugojului Sunt în Ruină de ani de zile. Redeșteptarea. 18 June 2013. Available online: https://redesteptarea.ro/galerie-foto-cele-mai-multe-cldiri-emblem-ale-lugojului-sunt-in-ruin-de-ani-de-zile/ (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Creţan, R. Mapping protests against dog culling in post-communist Romania. Area 2015, 47, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandi, M. Urban nature and ecological imaginary. In The Routledge Companion to Urban Imaginaries; Lindner, C., Meissner, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Matichescu, M.L.; Drăgan, A.; Lucheș, D. Channels to West: Exploring the Migration Routes between Romania and France. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1861. [Google Scholar]

- City Hall of the Municipality of Lugoj. The Strategy of Urban Development of the Municipality of Lugoj; Nagard: Lugoj, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ilovan, O.R.; Jordan, P.; Havady-Nagy, K.X.; Zametter, T. Identity matters for development. Austrian and Romanian experiences. Transylvanian Rev. 2016, 25, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Neoliberalization: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development; Franz Steiner Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Interviews | No. of Interviews and Personal Conversations | Area | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | 4 interviews | 4 | Not applicable | Semi-structured interviews with 15 questions, duration of 60 min each. The questions revolved around on the production of derelict places and their further possibilities of regeneration. |

| City Hall representative | 1 | |||

| Former directors of ruined factories | 3 | |||

| Personal conversations | Former workers | 5 | Northern Industrial Area | The subjects were randomly intercepted and personal conversation were designed as free conversation to capture the individuals (former workers and residents no-workers) perceptions on the local ruined sites and on related aspects regarding their opinions concerning the quality of life and the urban landscape as well as their position towards further regeneration. |

| Residents | 10 | |||

| Former workers | 5 | Southern Industrial Area | ||

| Residents | 10 | |||

| Former workers | 5 | Central Industrial Area | ||

| Residents | 10 | |||

| Former workers | 5 | Western Industrial area | ||

| Residents | 10 | |||

| Inventory of the local derelict sites | 1 | All derelict areas | Based on personal observation and field trip-research. The inventory is summarized in Table 2. |

| Area | Plants | Attested | Cultural Identity | Industrial Traditions and Lost Productions | Preserved Production | Post-Socialist Status | New Post-Socialist Economies | Types of Ruins | Commentaries Causes of Dereliction or Restructuring |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western industrial area | ITL Unit A | 1907 | textiles production | textiles, canvas and Damascus | - | completely derelict | - | industrial ruins | deindustrialization, plant closure |

| Southern industrial areas | Bricks Factory | 1888 | bricks production, the factory was founded by J. Muschong, one of the richest business persons in earlier capitalism | bricks | new types of bricks to a small extent | derelict plant to a large extent | - | industrial ruins | deindustrialization, plant closure to a large extent |

| Central industrial area | ITL Unit C | 1907 | textiles production | textiles | - | completely derelict | - | industrial ruins | deindustrialization, plant closure |

| The Milk Factory | 1942 | cultural tradition in casein and milk products | food industry | - | completely derelict | - | industrial ruins | deindustrialization, plant closure | |

| The lasts Factory | 1910 | lasts and shoes production | lasts and shoes | - | completely derelict | - | industrial ruins | deindustrialization, plant closure | |

| The rail transport area | 1970 | connection between industry and rail transport | - | - | partly derelict | - | rail transport ruins | deindustrialization, the failure of rail infrastructure connected to the local industry; | |

| Northern Industrial Area | The Slaughter-house | 1912 | cultural tradition in food—patri-mony building | food | - | completely derelict | - | industrial ruins | deindustrialization and reindustrialization but derelict |

| Natural Silk Mill (FMN) | 1907 | cultural tradition in natural silk production (unique in Romania with international markets) | natural silk | textiles | restructured but partly derelict | industry, tertiary activities | industrial ruins | deindustrialization, privatization, mismanagement plant closure, fragmentation, | |

| IURT Plant | 1970 | state-socialist plant | machinery | machinery | restructured and partly derelict | machinery, shoes | industrial ruins | reindustrialization, tertiarization a part of it was privatized through Romanian capital, while other part was purchased by Rieker, reindustrialization. | |

| IUPS Plant | 1974 | state-socialist plant | spare parts | spare parts | restructured and partly derelict | machines spare parts | industrial ruins | in the beginning, the plant was privatized through Romanian capital | |

| The brick factory | 1888 | cultural tradition under earlier capitalism | bricks and tills | - | completely derelict | - | industrial ruins | deindustrialization, plant closure | |

| Mondial Plant | 1900 | cultural tradition in materials for constructions | - | sanitary products | functioning | sanitary production | - | reindustrialization, privatized through FDIs, completely purchased by the German Company Villeroy and Boch | |

| Military Area | 1960 | important military site under state-socialism | sanitary products | - | to a large extent derelict | - | military ruins | cities’ demilitarization, since the Romania access to NATO and professional army. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jucu, I.S.; Voiculescu, S. Abandoned Places and Urban Marginalized Sites in Lugoj Municipality, Three Decades after Romania’s State-Socialist Collapse. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187627

Jucu IS, Voiculescu S. Abandoned Places and Urban Marginalized Sites in Lugoj Municipality, Three Decades after Romania’s State-Socialist Collapse. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187627

Chicago/Turabian StyleJucu, Ioan Sebastian, and Sorina Voiculescu. 2020. "Abandoned Places and Urban Marginalized Sites in Lugoj Municipality, Three Decades after Romania’s State-Socialist Collapse" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187627