Managing Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility Efficiently: A Review of Existing Literature on Business Groups and Networks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. The Link between Sustainability, Sustainable Development Goals and Corporate Social Responsibility

2.2. Considering the Potential Impact o Small and Medium-Sized Business Groups on Sustainable Development

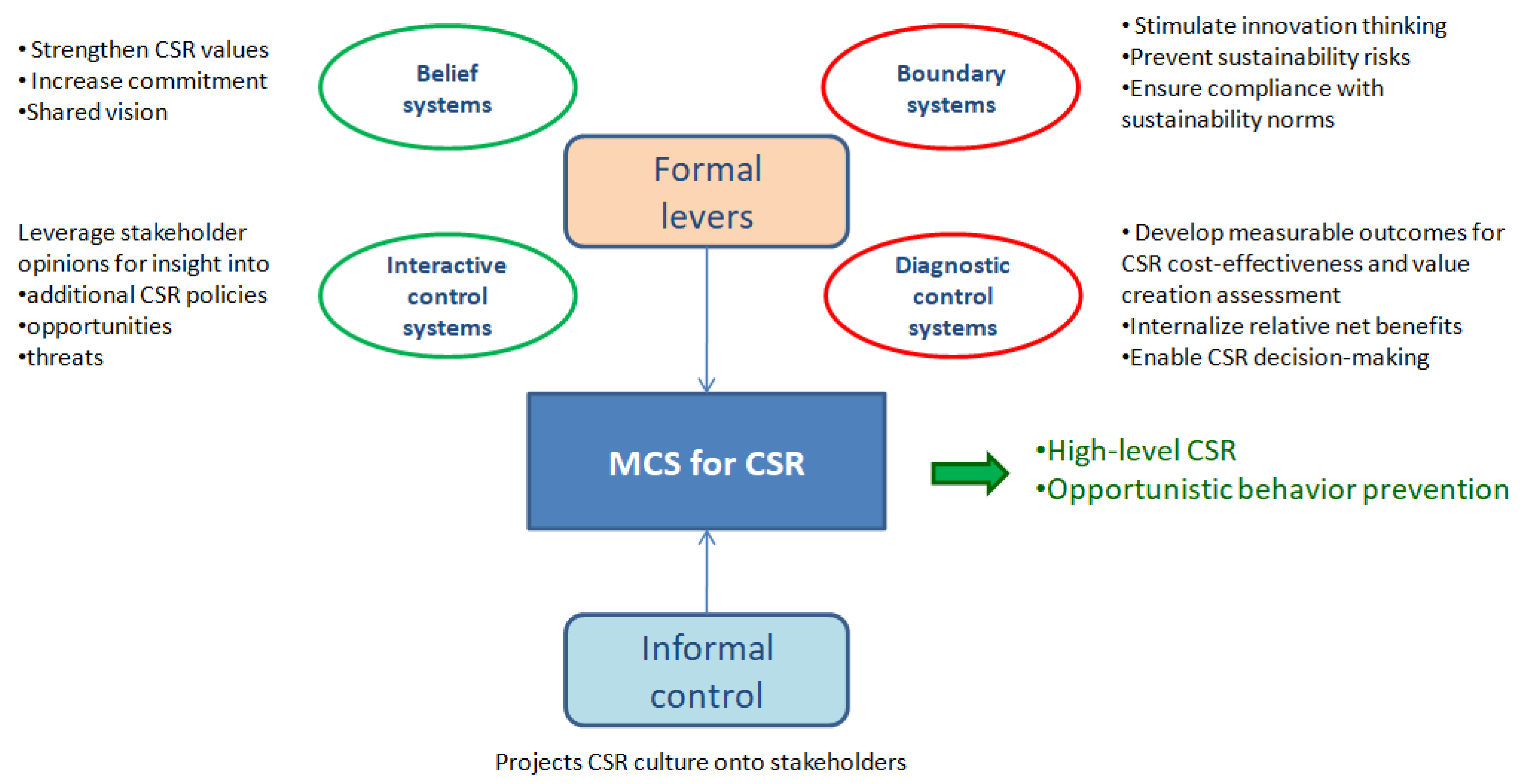

2.3. Management Control Systems for Sustainability

3. Methodology

3.1. Choice of Keywords and Selection Criteria

- (a)

- Business/corporate/manufacturing group, group of companies, intercompany, intragroup, SME network;

- (b)

- Sustainability, sustainable management, sustainable development (goals), responsibility ethics, corporate social responsibility, corporate social performance, corporate sustainability, environmental social governance performance (ESG);

- (c)

- Management control (system), management/managerial accounting, cost accounting/management, strategic control, corporate governance, board of directors.

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Study Screening and Selection

3.4. Extraction and Synthesis of Sources

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Analysis: Literature Trends

4.2. Content Analysis

4.2.1. The Influence of Group Affiliation and Networks on the Intensity of CSR Implementation

4.2.2. Systems and Tools for Sustainability Management in SMEs

4.2.3. CSR Processes in SME Networks and Corporate Groups

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors, Year | BG or SME | Journal | Country of Research | Scope of Analysis | Research Type and Method | Topics | Limitations for Own Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [82] | (Vásquez et al. 2019) | SME | Journal of Cleaner Production | Colombia, Italy | Emerging market (Colombia) | Eql (survey): discussion of findings | S. sustainability strategy M. organizational culture SM. EMS, eco-efficiency, MEC | focus on SMEs in an emerging country |

| [70] | (Kim et al. 2018) | BG | Management Research Review | USA, South Korea | Emerging market (South Korea) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, regressions (univariate and multivariate), correlations (Pearson) | S. CSR, legal environment M. ERC | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [84] | (Johnstone 2020) | SME | Journal of Cleaner Production | Sweden | None | C (review): literature analysis | M. MAC SM. EMS | focus on SMEs |

| [106] | (Chang, Cheng 2019) | SME | Journal of Cleaner Production | Taiwan | Emerging market (Taiwan) | Eqn (cases analysis): integrated multi-attribute decision analysis model (FDM, GRA, RST) | S. SD, TBL M. generic economic variables | focus on SMEs in an emerging country |

| [6] | (Ray, Ray Chaudhuri 2018) | BG | Journal of Business Ethics | India | Emerging market (India) | Eqn (survey): descriptive stats, correlations | S. CSS, stock of fungible resources M. generic economic variable (debt ratio) | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [66] | (Ararat et al. 2018) | BG | Journal of Business Ethics | Turkey, Japan, Canada | Emerging markets (mainly) | C (review): literature analysis | S. CSR, public good M. corporate citizenship | focus on emerging markets and public goods, no MCS analysis |

| [59] | (Choi et al. 2018) | BG | Journal of Business Ethics | USA, Australia, UAE | Emerging market (South Korea) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, regressions (multivariate), correlations (bivariate) | S. CSR | focus on an emerging country, certain important factors influencing CSR decisions are neglected, no MCS analysis |

| [68] | (Guo et al. 2018) | BG | Emerging Markets Review | Canada, China | Emerging market (China) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, regressions (univariate, multivariate), correlations (Pearson) | S. CSR M. generic economic variables (ROA, cash, leverage debts/assets) | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [98] | (Kaspersen, Johansen 2016) | BG | Journal of Business Ethics | Denmark | One group (UtilGroup, Denmark) | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | M. auditability SM. SER | focus on one multinational group |

| [67] | (Agnihotri, Bhattacharya 2019) | BG | Journal of Marketing Communications | USA, UK | Emerging market (India) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, linear regression (multiple) | S. CSR M. internationalization, generic economic variables (profitability, sales) | focus on an emerging country |

| [65] | (Montecchia, Di Carlo 2015) | BG | International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics | Italy | Italy | Eqn (cases analysis): content analysis | S. CSD M. generic economic variables | focus on publicly listed companies in one country |

| [101] | (Del Baldo 2012) | SME BG | Journal of Management & Governance | Italy | Italy | Eql (cases analysis): discussion of findings | S. CSR M. business ethics SM. social control | social control is only mentioned |

| [60] | (Kim, Oh 2019) | BG | Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja | Kazakhstan, South Korea | Emerging market (India) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, correlations, panel regression | S. CSR M. generic economic variables (profitability, leverage/financial risk, sales growth) | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [69] | (Choi et al. 2013) | BG | Corporate Governance: An International Review | Australia, South Korea | Emerging market (South Korea) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, linear regressions (OLS, 2SLS), correlations | S. CSP M. generic economic variables (leverage, ROA) | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [5] | (Choi et al. 2019) | BG | Pacific-Basin Finance Journal | USA, South Korea | Emerging market (South Korea) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, regressions (logistic and linear OLS of Tobin’s Q), correlations | S. CSR, financial donations M. generic economic variables (leverage, profitability) | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [92] | (Marco-Fondevila et al. 2018) | SME | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | Spain | Spain | Eqn (experiment): distributions, linear regression (ANOVA), correlations | S. CS, EDA M. generic economic variables (profitability, EBITDA, turnover) SM. ESA | focus on SMEs |

| [100] | (Akiyama 2010) | BG | Asian Business & Management | Japan | One group (Sekisui House, Japan) | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | S. CSR, environmental management M. interorganizational-networks | focus on one BG, too project-specific, no MCS analysis |

| [63] | (Chauhan, Kumar 2018) | BG | Emerging Markets Review | India | Emerging market (India) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, regressions (multivariate of Tobin Q), correlations | S. ESG M. generic economic variables (cost of equity/debt/capital, cash flow, ROA) | focus on an emerging country |

| [32] | (Woo et al. 2014) | SME BG | Sustainability | South Korea | Emerging market (South Korea) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, regressions (multivariate), correlations | S. EI | focus on an emerging country, environmental accounting is only mentioned |

| [76] | (Singh et al. 2018) | SME | Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing | Malaysia | Emerging market (one SME, India) | Eqn (cases analysis): sustainability evaluation method (FAHP, FIS) | S. sustainability evaluation M. BSC framework | focus on one SME in an emerging country |

| [107] | (Feiock et al. 2014) | BG | Urban Affairs Review | USA, South Korea | USA | Eqn (survey): hierarchical model | S. local sustainability | focus on local programs and policies (macro not micro), survey of local officials instead of companies, no MCS analysis |

| [74] | (Klewitz 2017) | SME | Innovation: The European Journal of Social Sciences | Germany | Germany | Eql (cases analysis): discussion of findings | S. SOI M. knowledge network SM. sustainability BSC | focus on SME networks |

| [62] | (Lee 2018) | BG | The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business | South Korea | Emerging market (South Korea) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, regressions (Probit), correlations (Pearson) | S. CSR M. generic economic variables (ROA, leverage) | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [3] | (von Weltzien Høivik, Shankar 2011) | SME BG | Journal of Business Ethics | Norway | Norway | C (review): literature analysis | S. CSR M. network, CBA, risk management | focus on SME networks |

| [108] | (Suriya, Sudtasan 2014) | BG | Business & Economic Horizons | Thailand | Emerging market (Thailand) | C (presentation of an empirical method): description of an econometric model | S. CSR, SD SM. sustainable profit | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [7] | (Hosoda 2018) | SME | Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Effective Board Performance | Japan | One SME (Japan) | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | S. CSR SM. MCS-CSR integration | focus on one SME |

| [109] | (López-Pérez et al. 2017) | SME | Business Strategy & the Environment | Spain | Spain | Eqn (experiment): test of the causal paths through bootstrapping | S. CSR M. generic financial value variable SM. financial and non-financial outcomes | focus on SMEs |

| [78] | (Sulong et al. 2015) | SME | Journal of Cleaner Production | Malaysia | Emerging market (one SME, Malaysia) | Eql (cases analysis): discussion of findings | SM. MFCA | focus on one SME in an emerging country |

| [110] | (Acar et al. 2015) | BG | Tekstil ve Konfeksiyon | Turkey | Emerging market (one group, Turkey) | Eqn (case analysis): TOPSIS method | S. sustainability performance M. MCDM | focus on one BG in an emerging country, no MCS analysis |

| [73] | (Halila 2007: 14001) | SME | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | Sweden | One SME network (Sweden) | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | S. EI M. network SM. EMS | focus on one SME network |

| [64] | (Terlaak et al. 2018) | BG | Journal of Business Ethics | USA, South Korea | Emerging market (South Korea) | Eqn (experiment): logistic regression, correlations | S. environmental performance M. generic economic variables (ROA, leverage) | focus on an emerging country |

| [61] | (Panicker 2017) | BG | Social Responsibility Journal | India | Emerging market (India) | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, regressions (Tobit), correlations | S. CSR M. ownership SM. generic economic variable (profitability) | focus on publicly listed companies in an emerging country |

| [111] | (Murillo, Lozano 2009) | SME | Business Ethics: A European Review | Spain | One project (Spain) | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | S. CSR M. network | focus on public policy perspective and one project, no MCS analysis |

| [91] | (Girella et al. 2019) | SME | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | Italy | Italy (3 firms) | Eql (cases analysis): discussion of findings | S. SD, integrated reporting (GRI) | focus on SMEs, limited empirical sample, no specific metric described, GRI economic metrics as dummy variable only |

| [112] | (Halme Korpela 2014) | SME | Business Strategy & the Environment | Finland | Nordic countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland) | Eql (cases analysis): discussion of findings | S. SD, responsible innovations | focus on SMEs, no MCS analysis |

| [113] | (Corazza 2018) | SME BG | Journal of Applied Accounting Research | Italy | Bulgaria, Italy, Spain | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | S. CSR, ISO 26000 SM. SER | limited empirical sample (6 firms in 3 EU countries) |

| [90] | (Laurinkevičiūtė, Stasiškienė 2011) | SME | Clean Technologies & Environmental Policy | Lithuania | One SME (Lithuania) | Eqn (case analysis): analysis of sustainability costs, NPV, CSDI | SM. SMS, EMA, SMA, CSDI | focus on one SME |

| [114] | (Moore, Manring 2009) | SME | Journal of Cleaner Production | USA | None | C (review): literature analysis | S. CSR, CER M. network SM. sustainable supply chain management | focus on SMEs, no MCS analysis |

| [115] | (Shashi et al. 2018) | SME | Benchmarking: An International Journal | India, Italy, The Netherlands | Emerging market (India) | Eqn (experiment): exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, strumental equation modeling | S. sustainability orientation M. generic cost performance variable | focus on SMEs |

| [77] | (Nigri, Del Baldo 2018) | SME | Sustainability | Italy | Italy | Eql (cases analysis): discussion of findings | S. CSR, SIA SM. SMA system, SPMS, benefit corporation | focus on SMEs, limited empirical sample (7) |

| [97] | (Laurinkevičiūtė, Stasiškienė 2010) | SME | Environmental Research, Engineering & Management | Lithuania | One SME (Lithuania) | Eqn (case analysis): analysis of sustainability costs, NPV, CSDI | SM. EMA, SMA, CSDI | focus on one SME |

| [75] | (Lopez-Valeiras et al. 2015) | SME | Sustainability | Spain | Spain, Portugal | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, psychometric properties of measures, discriminant validity coefficient, regressions (PLS), correlations | S. SOI M. traditional (cost accounting, budget system) and contemporary (balanced scorecard, benchmarking) MCS | a limited number of MACS tools is considered |

| [116] | (Ciasullo, Troisi 2013) | SME BG | TQM Journal | Italy | One group (Italy) | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | SM. sustainable value creation | focus on one BG |

| [72] | (Daddi, Iraldo 2016) | SME | International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology | Italy | One SME network (Italy) | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | M. industrial cluster policies SM. EMS, eco-management and audit | focus on one SME network |

| [117] | (Dávila, Dávila 2014) | BG | Australian Economic History Review | Colombia | Emerging market (one group, Fundación Social, Colombia) | Eql (case analysis): discussion of findings | S. CSR | focus on one BG in an emerging country, no MCS analysis |

| [118] | (Sudthanom 2016) | BG | UTCC International Journal of Business & Economics | Thailand | Emerging market (Thailand) | Eql (cases analysis): content analysis | S. CSR M. IMC | focus on an emerging country, limited CSR analysis |

| [119] | (Stekelorum et al. 2019) | SME | Applied Economics | France, Morocco | France | Eqn (experiment): descriptive stats, multiple mediation analysis, correlations | S. CSR M. supply chain, generic economic variable | focus on SMEs |

| [94] | (Johnson, Schaltegger 2016) | SME BG | Journal of Small Business Management | Germany | None | C (review): literature analysis | SM. generic (benchmarking, sustainability BSC and reporting, QMS, EMS, social management systems) and SME-specific (eco-mapping, EPM-Kompas, SAFE, SERS) sustainability management tools | focus on SMEs, only brief mention of the facilitating nature of group and network-oriented tools |

References

- OECD. Enhancing the Contributions of SMEs in a Global and Digitalised Economy; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, N.R.; Wood, J.D. Foundations of Sustainable Business: Theory, Function, and Strategy, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-119-57750-8. [Google Scholar]

- von Weltzien Høivik, H.; Shankar, D. How Can SMEs in a Cluster Respond to Global Demands for Corporate Responsibility? J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Boucher, X.; Afsarmanesh, H. The Role of Collaborative Networks in Sustainability. In Collaborative Networks for a Sustainable World; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-3-642-15960-2. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.K.; Han, S.; Kwon, Y. CSR activities and internal capital markets: Evidence from Korean business groups. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2019, 55, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Ray Chaudhuri, B. Business Group Affiliation and Corporate Sustainability Strategies of Firms: An Investigation of Firms in India. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 955–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, M. Management control systems and corporate social responsibility: Perspectives from a Japanese small company. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 18, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjaliès, D.-L.; Mundy, J. The use of management control systems to manage CSR strategy: A levers of control perspective. Manag. Account. Res. 2013, 24, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, A. The 3 Pillars of Corporate Sustainability. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/100515/three-pillars-corporate-sustainability.asp#citation-1 (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Johnston, P.; Everard, M.; Santillo, D.; Robert, K.-H. Reclaiming the Definition of Sustainability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2007, 14, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; p. 383. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.; Allen, S. Sustainability and Sustainable Development—What is Sustainability and What Is Sustainable Development? Available online: https://www.circularecology.com/sustainability-and-sustainable-development.html (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diesendorf, M. Models of sustainability and sustainable development. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2001, 1, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavič, P.; Lukman, R. Review of sustainability terms and their definitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M. Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Int. Soc. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Agenda. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Ashrafi, M.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R.; Magnan, G.M. How corporate social responsibility can be integrated into corporate sustainability: A theoretical review of their relationships. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, L.N. The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (Csr) And Sustainable Development (Sd). Intern. Audit. Risk Manag. 2015, 38, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- UN Global Compact; GRI. WBCSD SDG Compass—The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs. Available online: https://sdgcompass.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/019104_SDG_Compass_Guide_2015.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Lueg, R.; Radlach, R. Managing sustainable development with management control systems: A literature review. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazeri, G.T.; Anholon, R.; da Silva, D.; Cooper Ordoñez, R.E.; Gonçalves Quelhas, O.L.; Filho, W.L.; de Santa-Eulalia, L.A. An assessment of the integration between corporate social responsibility practices and management systems in Brazil aiming at sustainability in enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnea, I.C.; Olaru, M.; Moisa, C. Relationship between corporate social responsibility and social sustainability. Econ. Transdiscipl. Cogn. 2011, 14, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W. The Age of Responsibility: CSR 2.0 and the New DNA of Business. J. Bus. Syst. Gov. Ethics 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W. CSR 2.0: The Evolution and Revolution of Corporate Social Responsibility. In Responsible Business: How to Manage a CSR Strategy Successfully; Pohl, M., Tolhurst, N., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 311–328. ISBN 978-1-119-20615-6. [Google Scholar]

- Behringer, K.; Szegedi, K. The Role Of CSR In Achieving Sustainable Development—Theoretical Approach. Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendtorff, J.D. Sustainable Development Goals and progressive business models for economic transformation. Local Econ. 2019, 34, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönherr, N.; Findler, F.; Martinuzzi, A. Exploring the interface of CSR and the Sustainable Development Goals. Transnatl. Corp. 2017, 24, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- KPMG. The Road Ahead—The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2017; KPMG: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tajeddin, M.; Carney, M. African Business Groups: How Does Group Affiliation Improve SMEs’ Export Intensity? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 43, 1194–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, C.; Chung, Y.; Chun, D.; Seo, H. Exploring the Impact of Complementary Assets on the Environmental Performance in Manufacturing SMEs. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7412–7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A. Business groups and their types. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2006, 23, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamin, A. Business Groups as Information Resource: An Investigation of Business Group Affiliation in the Indian Software Services Industry. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1487–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J.; Máté, D. Does Business Group Affiliation Matter for Superior Performance? Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arkalgud, A.P. Filling “Institutional Voids” in Emerging Markets. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/infosys/2011/09/20/filling-institutional-voids-in-emerging-markets/#2f123a2d65cc (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- Wuest, T.; Thoben, K.-D. Information Management for Manufacturing SMEs. In Advances in Production Management Systems. Value Networks: Innovation, Technologies, and Management; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Frick, J., Laugen, B.T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 384, pp. 481–488. ISBN 978-3-642-33979-0. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Horizon 2020 SME Instrument; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wijethilake, C.; Munir, R.; Appuhami, R. Environmental Innovation Strategy and Organizational Performance: Enabling and Controlling Uses of Management Control Systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, L.; Herremans, I. Ethical behaviours in organizations: Directed by the formal or informal systems? J. Bus. Ethics 1995, 14, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heales, J.; Susilo, A.; Rohde, F.H. Project Management Effectiveness: The choice—Formal or informal controls. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanthi Herath, S. A framework for management control research. J. Mgmt Dev. 2007, 26, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R. Levers of Control. How Managers Use Innovative Control. Systems to Drive Strategic Renewal; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-87584-559-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda, M.; Suzuki, K. Using Management Control Systems to Implement CSR Activities: An Empirical Analysis of 12 Japanese Companies: Management Control Systems for Implementing CSR Activities. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 24, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguir, L.; Laguir, I.; Tchemeni, E. Implementing CSR activities through management control systems: A formal and informal control perspective. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden, C. Towards a Socially Responsible Management Control System. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beusch, P.; Rosén, M.; Frisk, E.; Dilla, W.N. Management Control for Sustainability: The Development of a Fully Integrated Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2016 Management Accounting Section Meeting: Research and Case Conference, Dallas, TX, USA, 6–9 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, B. Management Control Systems to support Sustainability and Integrated Reporting. In Sustainability Accounting and Integrated Reporting; De Villiers, C., Maroun, W., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-315-10803-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, J.; Rouse, P.; De Villiers, C. Sustainability reporting integrated into management control systems. Pac. Account. Rev. 2015, 27, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L. Theorising and conceptualising the sustainability control system for effective sustainability management. J. Manag. Control. 2019, 30, 25–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Souza, A.C.; Costa Alexandre, N.M.; De Brito Guirardello, E. Psychometric properties in instruments evaluation of reliability and validity. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2017, 26, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Loke, J. Rigour and Robustness in Research. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/DrJenniferLoke/rigour-robustness-in-research-16-april-2015 (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Olsen, W. Triangulation in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods Can Really Be Mixed. Dev. Sociol. 2004, 20, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D. Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Available online: https://www.quirkos.com/blog/post/triangulation-in-qualitative-research-analysis (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Leung, L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.J.; Jo, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, M. Business Groups and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 931–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Oh, S. Corporate social responsibility, business groups and financial performance: A study of listed Indian firms. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2019, 32, 1777–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panicker, V.S. Ownership and corporate social responsibility in Indian firms. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. Group-Affiliated Firms and Corporate Social Responsibility Activities. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2018, 5, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, Y.; Kumar, S.B. Do investors value the nonfinancial disclosure in emerging markets? Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2018, 37, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlaak, A.; Kim, S.; Roh, T. Not Good, Not Bad: The Effect of Family Control on Environmental Performance Disclosure by Business Group Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 977–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecchia, A.; Di Carlo, E. Corporate Social Disclosure under Isomorphic Pressures: Evidence from Business Groups. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethics 2015, 10, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ararat, M.; Colpan, A.M.; Matten, D. Business Groups and Corporate Responsibility for the Public Good. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 911–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agnihotri, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Communicating CSR practices—Role of internationalization of emerging market firms. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, M.; He, L.; Zhong, L. Business groups and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2018, 37, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Lee, D.; Park, Y. Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Governance and Earnings Quality: Evidence from Korea. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2013, 21, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Seol, I.; Kang, Y. A study on the earnings response coefficient (ERC) of socially responsible firms: Legal environment and stages of corporate social responsibility. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 1010–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, C.; Stanco, M.; Marotta, G. The Life Cycle of Corporate Social Responsibility in Agri-Food: Value Creation Models. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. The effectiveness of cluster approach to improve environmental corporate performance in an industrial district of SMEs: A case study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halila, F. Networks as a means of supporting the adoption of organizational innovations in SMEs: The case of Environmental Management Systems (EMSs) based on ISO 14001. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2007, 14, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J. Grazing, exploring and networking for sustainability-oriented innovations in learning-action networks: An SME perspective. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 30, 476–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Valeiras, E.; Gomez-Conde, J.; Naranjo-Gil, D. Sustainable Innovation, Management Accounting and Control Systems, and International Performance. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3479–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, S.; Olugu, E.U.; Musa, S.N.; Mahat, A.B. Fuzzy-Based sustainability evaluation method for manufacturing SMEs using balanced scorecard framework. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigri, G.; Del Baldo, M. Sustainability Reporting and Performance Measurement Systems: How do Small- and Medium-Sized Benefit Corporations Manage Integration? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sulong, F.; Sulaiman, M.; Norhayati, M.A. Material Flow Cost Accounting (MFCA) enablers and barriers: The case of a Malaysian small and medium-sized enterprise (SME). J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. IUCN Environmental and Social Management System (ESMS)—Manual; IUCN: Grand, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, G.; Mazzocchetti, A.; Rapallo, I.; Tayser, N.; Cincotti, S. Assessment of the Economic and Social Impact Using SROI: An Application to Sport Companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WBCSD. Eco-Efficiency—Learning Module; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, J.; Aguirre, S.; Fuquene-Retamoso, C.E.; Bruno, G.; Priarone, P.C.; Settineri, L. A conceptual framework for the eco-efficiency assessment of small- and medium-sized enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.-F.; Journeault, M. Eco-Control: The influence of management control systems on environmental and economic performance. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L. A systematic analysis of environmental management systems in SMEs: Possible research directions from a management accounting and control stance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Integrated Standards Compare ISO 9001 to ISO 14001—How does ISO 9001 Compare to ISO 14001? Available online: https://integrated-standards.com/compare-management-system-structure/compare-iso-9001-iso-14001/ (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Koroljova, A.; Voronova, V. Eco-Mapping as a Basis for Environmental Management Systems Integration at Small and Medium Enterprises. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2007, 18, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIA. Eco-Mapping Tool. Available online: https://www.sia-toolbox.net/solution/eco-mapping (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Günther, E.; Kaulich, S. The EPM-KOMPAS: An instrument to control the environmental performance in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2005, 14, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFAC. Environmental Management Accounting: International Guidance Document; International Federation of Accountants: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-931949-46-0. [Google Scholar]

- Laurinkevičiūtė, A.; Stasiškienė, Ž. SMS for decision making of SMEs. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2011, 13, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girella, L.; Zambon, S.; Rossi, P. Reporting on sustainable development: A comparison of three Italian small and medium-sized enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Fondevila, M.; Moneva Abadía, J.M.; Scarpellini, S. CSR and green economy: Determinants and correlation of firms’ sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 756–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haggar, S.; Samaha, A. Sustainability Management System. In Roadmap for Global Sustainability—Rise of the Green Communities; Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 49–58. ISBN 978-3-030-14583-5. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Two Decades of Sustainability Management Tools for SMEs: How Far Have We Come? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohn, H.; Baedeker, C.; Liedtke, C. SAFE—Sustainability Assessment For Enterprises: Die Methodik. Ein Instrument zur Unterstützung einer zukunftsfähigen Unternehmens- und Organisationsentwicklung. Wupp. Pap. 2001, 112, 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kakabadse, A.; Morsing, M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Reconciling Aspiration with Application; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-230-59957-4. [Google Scholar]

- Laurinkevičiūtė, A.; Stasiškienė, Ž. Sustainable Development Decision-Making Model for Small and Medium Enterprises. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2010, 52, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspersen, M.; Johansen, T.R. Changing Social and Environmental Reporting Systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Gray, R. Social and Environmental Reporting and the Business Case; Certified Accountants Educational Trust: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-85908-432-8. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, T. CSR and inter-organisational network management of corporate groups: Case study on environmental management of Sekisui House Corporation Group. Asian Bus. Manag. 2010, 9, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, M. Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance in Italian SMEs: The experience of some “spirited businesses”. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, D.W. Business Groups are Driving Economic Growth in Emerging Economies. Available online: https://cbk.bschool.cuhk.edu.hk/business-groups-are-driving-economic-growth-in-emerging-economies/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Ecorys. Business Networks—Final Report; Ecorys: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- do Carmo Farinha, L.M.; de Matos Ferreira, J.J.; Borges Gouveia, J.J. Innovation and Competitiveness: A High-Tech Cluster Approach. Rom. Rev. Precis. Mech. Optics Mechatron. 2014, 45, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ecorys. Study on Business Networks; Ecorys: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-T. Analysis model of the sustainability development of manufacturing small and medium- sized enterprises in Taiwan. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C.; Portney, K.E.; Bae, J.; Berry, J.M. Governing Local Sustainability: Agency Venues and Business Group Access. Urban Aff. Rev. 2014, 50, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriya, K.; Sudtasan, T. How to estimate the model of sustainable profit and corporate social responsibility. Bus. Econ. Horiz. 2014, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, M.E.; Melero, I.; Sese, F.J. Management for Sustainable Development and Its Impact on Firm Value in the SME Context: Does Size Matter? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 985–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, E.; Kiliç, M.; Güner, M. Measurement of sustainability performance in textile industry by using a multi-criteria decision making method. Tekst. Konfeksiyon 2015, 25, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, D.; Lozano, J.M. Pushing forward SME CSR through a network: An account from the Catalan model. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halme, M.; Korpela, M. Responsible Innovation toward Sustainable Development in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Resource Perspective. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2014, 23, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, L. Small business social responsibility: The CSR4UTOOL web application. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2018, 19, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.B.; Manring, S.L. Strategy development in small and medium sized enterprises for sustainability and increased value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashi, K.; Cerchione, R.; Centobelli, P.; Shabani, A. Sustainability orientation, supply chain integration, and SMEs performance: A causal analysis. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3679–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Troisi, O. Sustainable value creation in SMEs: A case study. TQM J. 2013, 25, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila, C.; Dávila, J.C. The Evolution of a Socially Committed Business Group in Colombia. Aust. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2014, 54, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudthanom, T. The relationship between integrated marketing communication and marketing communications’ objectives of marketing directors in Thailand. UTCC Int. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 8, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Stekelorum, R.; Laguir, I.; Elbaz, J. Transmission of CSR requirements in supply chains: Investigating the multiple mediating effects of CSR activities in SMEs. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 4642–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BG’s Advantages for SMEs | SMEs Advantages for BGs | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Structural |

|

|

| 2. Informational |

|

|

| 3. Sustainability |

|

|

| EBSCO | Wiley | WOS | Sustainability | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keyword Combinations | Tot. | Incl. | Tot. | Incl. | Tot. | Incl. | Tot. | Incl. | TOTAL | INCLUDED | ||

| I (SME) | 21 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 28 | 9 | ||

| I (BG) | 5 | 2 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 24 | 2 | ||

| II | 420 | 69 | 196 | 5 | 67 | 15 | 13 | 2 | 696 | 91 | ||

| III | 48 | 12 | 16 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 88 | 12 | ||

| Total | 494 | 89 | 228 | 6 | 73 | 15 | 41 | 4 | 836 | 114 | 102 | 48 |

| pre-screen | 1st screen | 2nd screen | 3rd screen | |||||||||

| removed | 722 | 12 | 57 | |||||||||

| added | 0 | 0 | 3 | |||||||||

| Nr | TCMC | SuMC | SoM | EM | Int | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability and ethics (n = 25) | Journal of Business Ethics | 6 | X | X | |||

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 5 | X | X | ||||

| Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | 3 | X | X | ||||

| Sustainability | 3 | X | X | X | |||

| Business Strategy& the Environment | 2 | ||||||

| Business Ethics: A European Review | 1 | ||||||

| Clean Technologies &Environmental Policy | 1 | X | X | ||||

| Environmental Research, Engineering& Management | 1 | X | X | ||||

| International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics | 1 | ||||||

| International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology | 1 | X | |||||

| Social Responsibility Journal | 1 | ||||||

| Accounting and management (n = 12) | Asian Business & Management | 1 | |||||

| Benchmarking: An International Journal | 1 | ||||||

| Business &Economic Horizons | 1 | ||||||

| Corporate Governance: An International Review | 1 | ||||||

| Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Effective Board Performance | 1 | ||||||

| Journal of Applied Accounting Research | 1 | X | |||||

| Journal of Management &Governance | 1 | X | |||||

| Journal of Marketing Communications | 1 | ||||||

| Journal of Small Business Management | 1 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Management Research Review | 1 | ||||||

| TQM Journal | 1 | ||||||

| UTCC International Journal of Business & Economics | 1 | ||||||

| Economics (n = 3) | Applied Economics | 1 | |||||

| Australian Economic History Review | 1 | ||||||

| Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja | 1 | ||||||

| Finance (n = 4) | Emerging Markets Review | 2 | |||||

| Pacific-Basin Finance Journal | 1 | ||||||

| The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business | 1 | ||||||

| Public governance and policy (n = 2) | Innovation: The European Journal of Social Sciences | 1 | X | ||||

| Urban Affairs Review | 1 | ||||||

| Other (n = 2) | Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing | 1 | X | ||||

| Tekstilve Konfeksiyon (Textile and Apparel) | 1 |

| Variables (a) and Interaction Levels (b) | BG Implications for CSR | Network Implications for CSR |

|---|---|---|

| (a1) Size and age | More assets available (physical, financial, intellectual) to invest in CSR | Sum of different firm resources and capabilities in various business areas along the value chain |

(a2) Internal influence by

|

| Ongoing competitiveness stimulated through peer encouragement |

| (b1) Macro perspective: network/group to external environment |

|

|

| (b2) Mezo perspective: interactions between network/group members |

|

|

| (b3) Micro perspective: specific advantages for individual SMEs |

| |

| Stage | Activity Description | Actors |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Project initiation: commitment and acceptance | Trust-building through exchange of views on the best project

| All member companies |

| (2) Implementation of aggregation-wide base activities |

|

|

| (3) Decision to undergo ample change management |

| Top management: strategic decision |

| (4) Firm-level actions |

|

|

| (5) Make reporting auditable for legitimization |

|

|

| (6) Transition from CSR to territorial social responsibility (optional) | Diffusion of CSR across the local territory to

| Group/network (top management) |

Regional environmental management systems or EMAS schemes are fitted policy tools to

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liakh, O.; Spigarelli, F. Managing Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility Efficiently: A Review of Existing Literature on Business Groups and Networks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187722

Liakh O, Spigarelli F. Managing Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility Efficiently: A Review of Existing Literature on Business Groups and Networks. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187722

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiakh, Olena, and Francesca Spigarelli. 2020. "Managing Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility Efficiently: A Review of Existing Literature on Business Groups and Networks" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187722

APA StyleLiakh, O., & Spigarelli, F. (2020). Managing Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility Efficiently: A Review of Existing Literature on Business Groups and Networks. Sustainability, 12(18), 7722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187722