Plant-Based Food By-Products: Prospects for Valorisation in Functional Bread Development

Abstract

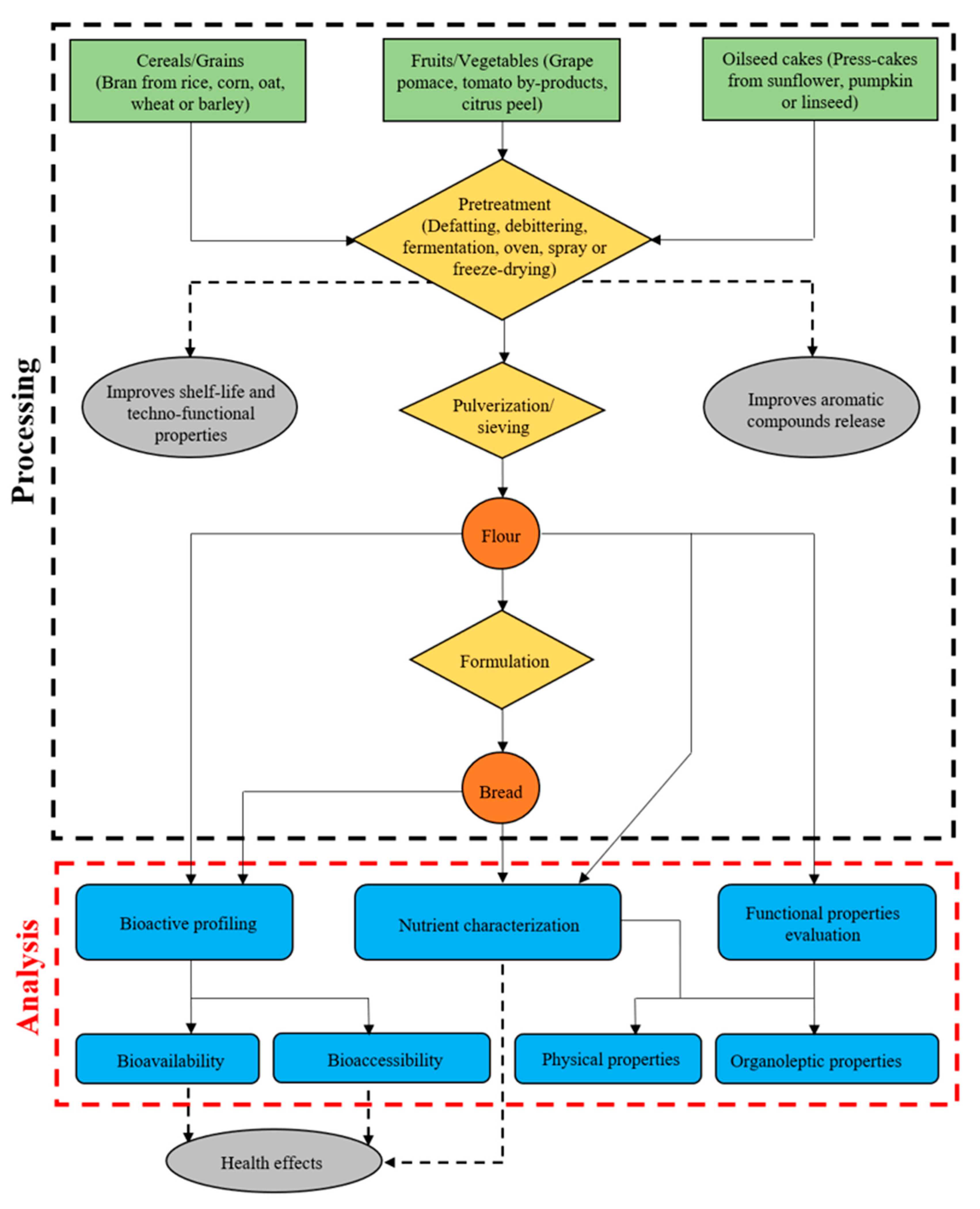

:1. Introduction

2. Bioactive Properties of Plant-Based Food By-Products from Industrial and Small-Scale Processing

3. Qualities of Functional Bread Containing Plant-Based By-Products

3.1. Fruit and Vegetable By-Product Valorization in Functional Bread

3.2. Cereals/Grains/Pseudo-Cereal Industrial By-Products Valorisation in Functional Bread

3.3. Oilseed and Seed by-Products Valorisation for Functional Bread Application

4. Bioactivity of Functional Bread Formulated with Food Processing By-Products

4.1. Fruit and Vegetable By-Products Utilisation in Bread and Effect on Bioactive Properties

4.2. Grain/Cereal, Pseudocereal By-Products Utilisation in Bread and Effect on Bioactive Properties

4.3. Tuber Processing By-Products Utilisation and Effects in Bioactive Properties

5. Sensory and Nutritional Profile of Functional Bread Formulated with Food By-Products

5.1. Fruit and Vegetable By-Products Utilisation in Bread and Effects on Sensory Profile

5.2. Grain/Cereal, Pseudocereal By-Product Utilisation in Bread and Effects on Sensory Profile

5.3. Oilseed By-Product Utilisation in Bread and Effects on Sensory and Nutrition Profile

6. Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility of Bioactive Compounds from Functional Bread formulated with Plant-Based By-Products

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Onipe, O.O.; Jideani, A.I.O.; Beswa, D. Composition and functionality of wheat bran and its application in some cereal food products. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporin, M.; Avbelj, M.; Kovac, B.; Mozina, S.S. Quality characteristics of wheat flour dough and bread containing grape pomace flour. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2018, 24, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordiga, M.; Travaglia, F.; Locatelli, M.; Arlorio, M.; Coïsson, J.D. Spent grape pomace as a still potential by-product. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 2022–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chareonthaikij, P.; Uan-On, T.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Effects of pineapple pomace fibre on physicochemical properties of composite flour and dough, and consumer acceptance of fibre-enriched wheat bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ranganathan, V.; Patti, A.; Arora, A. Valorisation of pineapple wastes for food and therapeutic applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 82, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Gallagher, E.; Bademunt, A.; Viñas, I.; Bobo, G.; Villaró, S.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Bioaccessibility, physicochemical, sensorial, and nutritional characteristics of bread containing broccoli co-products. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkijowska, A.; Zarzycki, P.; Sobota, A.; Nawrocka, A.; Blicharz-Kania, A.; Andrejko, D. The possibility of using by-products from the flaxseed industry for functional bread production. LWT 2020, 118, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarek-Tilistyák, J.; Agócs, J.; Lukács, M.; Dobró-Tóth, M.; Juhász-Román, M.; Dinya, Z.; Jekő, J.; Máthé, E. Novel breads fortified through oilseed and nut cakes. Acta Aliment. 2014, 43, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wadhwa, M.; Bakshi, M.P.S. Utilization of Fruit and Vegetable Wastes as Livestock Feed and as Substrates for Generation of Other Value-Added Products; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Rakha, A.; Butt, M.S.; Iqbal, M.J.; Rashid, S. Rice bran nutraceutics: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3771–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes, A.; Viveros, A.; Chamorro, S.; Arija, I. Use of polyphenol-rich grape by-products in monogastric nutrition. A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 211, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, D.M.; Kingston, W.; Jacob, F.; Titze, J.; Arendt, E.K.; Zannini, E. Wheat bread biofortification with rootlets, a malting by-product. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 2372–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, D.M.; Jacob, F.; Titze, J.; Arendt, E.K.; Zannini, E. Fibre, protein and mineral fortification of wheat bread through milled and fermented brewer’s spent grain enrichment. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 235, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, Y.S.; Lu, T.C.; Lin, C.C. Functional analysis of unfermented and fermented citrus peels and physical properties of citrus peel-added doughs for bread making. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 3803–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frutos, M.J.; Guilabert-Antón, L.; Tomás-Bellido, A.; Hernández-Herrero, J.A. Effect of artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) fiber on textural and sensory qualities of wheat bread. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2008, 14, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, V.; Ionica, M.E.; Trandafir, I. Bread enriched in lycopene and other bioactive compounds by addition of dry tomato waste. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 8260–8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kourkouta, L.; Koukourikos, K.; Iliadis, C.; Ouzounakis, P.; Monios, A.; Tsaloglidou, A. Bread and health. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 5, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keaveney, E.M.; Price, R.K.; Hamill, L.L.; Wallace, J.M.; McNulty, H.; Ward, M.; Strain, J.J.; Ueland, P.M.; Molloy, A.M.; Piironen, V.; et al. Postprandial plasma betaine and other methyl donor-related responses after consumption of minimally processed wheat bran or wheat aleurone, or wheat aleurone incorporated into bread. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boll, E.V.; Ekstrom, L.M.; Courtin, C.M.; Delcour, J.A.; Nilsson, A.C.; Bjorck, I.M.; Ostman, E.M. Effects of wheat bran extract rich in arabinoxylan oligosaccharides and resistant starch on overnight glucose tolerance and markers of gut fermentation in healthy young adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, D.; Wagner, A.; Schubert, R.; Jahreis, G. Tocopherol isomer pattern in serum and stool of human following consumption of black currant seed press residue administered in whole grain bread. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 28, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, C.S.; Bonwick, G.A. Ensuring the future of functional foods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 54, 1467–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartvigsen, M.L.; Gregersen, S.; Laerke, H.N.; Holst, J.J.; Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Hermansen, K. Effects of concentrated arabinoxylan and beta-glucan compared with refined wheat and whole grain rye on glucose and appetite in subjects with the metabolic syndrome: A randomized study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Nozaki, S.; Makita, M.; Yokozuka, S.; Fukudome, S.I.; Yanagisawa, T.; Aoe, S. Effects of whole grain wheat bread on visceral fat obesity in Japanese subjects: A randomized double-blind study. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2018, 73, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, G.E.; Lu, C.I.; Trogh, I.; Arnaut, F.; Gibson, G.R. A randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled cross-over study to determine the gastrointestinal effects of consumption of arabinoxylan-oligosaccharides enriched bread in healthy volunteers. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Damen, B.; Cloetens, L.; Broekaert, W.F.; Francois, I.; Lescroart, O.; Trogh, I.; Arnaut, F.; Welling, G.W.; Wijffels, J.; Delcour, J.A.; et al. Consumption of breads containing in situ-produced arabinoxylan oligosaccharides alters gastrointestinal effects in healthy volunteers. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martins, Z.E.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O. Food industry by-products used as functional ingredients of bakery products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.; Martinez, M.M. Fruit and vegetable by-products as novel ingredients to improve the nutritional quality of baked goods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2119–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, H.; Czajkowska, K.; Cichowska, J.; Lenart, A. What’s new in biopotential of fruit and vegetable by-products applied in the food processing industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Camargo, A.C.; Schwember, A.R.; Parada, R.; Garcia, S.; Maróstica Júnior, M.R.; Franchin, M.; Regitano-d’Arce, M.A.B.; Shahidi, F. Opinion on the hurdles and potential health benefits in value-added use of plant food processing by-products as sources of phenolic compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shahidi, F.; Yeo, J.D. Insoluble-Bound Phenolics in Food. Molecules 2016, 21, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, C.E.; Kundu-Champ, A. Maximizing polyphenol content to uncork the relationship between wine and cancer. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cao, H.; Ou, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Szkudelski, T.; Delmas, D.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, J. Dietary polyphenols and type 2 diabetes: Human study and clinical trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 59, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajerska, J.; Mildner-Szkudlarz, S.; Jeszka, J.; Szwengiel, A. Catechin stability, antioxidant properties and sensory profiles of rye breads fortified with green tea extracts. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2010, 49, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rauf, A.; Imran, M.; Orhan, I.E.; Bawazeer, S. Health perspectives of a bioactive compound curcumin: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 74, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesinski, G.B.; Reville, P.K.; Mace, T.A.; Young, G.S.; Ahn-Jarvis, J.; Thomas-Ahner, J.; Vodovotz, Y.; Ameen, Z.; Grainger, E.; Riedl, K.; et al. Consumption of soy isoflavone enriched bread in men with prostate cancer is associated with reduced proinflammatory cytokines and immunosuppressive cells. Cancer Prev. Res. 2015, 8, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharif, M.K.; Butt, M.S.; Anjum, F.M.; Khan, S.H. Rice bran: A novel functional ingredient. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Strappe, P.; Shang, W.T.; Zhou, Z.K. Functional peptides derived from rice bran proteins. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Xu, Y.; Beta, T.; Zhu, Z.; Shao, Y.; Bao, J. Bound phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of whole grain and bran of white, red and black rice. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Deussen, A. Effects of natural peptides from food proteins on angiotensin converting enzyme activity and hypertension. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 59, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Chan, E.C.Y. Bioactive peptides and protein hydrolysates: Research trends and challenges for application as nutraceuticals and functional food ingredients. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 1, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, X.S.; Cui, S.W.; Li, W.; Tsao, R. Isolation and characterization of wheat bran starch. Food Res. Int. 2008, 41, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontonio, E.; Lorusso, A.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Use of fermented milling by-products as functional ingredient to develop a low-glycaemic index bread. J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 77, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Karki, I.; Nordlund, E.; Heinio, R.L.; Poutanen, K.; Katina, K. Influence of particle size on bioprocess induced changes on technological functionality of wheat bran. Food Microbiol. 2014, 37, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smuda, S.S.; Mohsen, S.M.; Olsen, K.; Aly, M.H. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities of some cereal milling by-products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giordano, D.; Locatelli, M.; Travaglia, F.; Bordiga, M.; Reyneri, A.; Coisson, J.D.; Blandino, M. Bioactive compound and antioxidant activity distribution in roller-milled and pearled fractions of conventional and pigmented wheat varieties. Food Chem. 2017, 233, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandrán-Quintana, R.R.; Mercado-Ruiz, J.N.; Mendoza-Wilson, A.M. Wheat Bran Proteins: A Review of Their Uses and Potential. Food Rev. Int. 2015, 31, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Radenkovs, V.; Pugajeva, I.; Soliven, A.; Needs, P.W.; Kroon, P.A. Varied Composition of Tocochromanols in Different Types of Bran: Rye, Wheat, Oat, Spelt, Buckwheat, Corn, and Rice. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gornas, P.; Misina, I.; Gravite, I.; Soliven, A.; Kaufmane, E.; Seglina, D. Tocochromanols composition in kernels recovered from different apricot varieties: RP-HPLC/FLD and RP-UPLC-ESI/MS(n) study. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Mutalip, S.S.; Ab-Rahim, S.; Rajikin, M.H. Vitamin E as an Antioxidant in Female Reproductive Health. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, D.J.; Inglett, G.E.; Liu, S.X. Utilisation of corn (Zea mays) bran and corn fiber in the production of food components. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, A.D.; Salter, J.; Dettmar, P.W.; Chaplin, M.F. Dietary fibre, physicochemical properties and their relationship to health. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2000, 120, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajdakowska, M.; Gebski, J.; Zakowska-Biemans, S.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M. Willingness to eat bread with health benefits: Habits, taste and health in bread choice. Public Health 2019, 167, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, H.; Woo, K.S.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, B.; Choi, H.S.; Choi, Y.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.Y. Antioxidant compounds and antioxidant activities of methanolic extracts from milling fractions of oat. Korean J. Food Nutr. 2016, 45, 1681–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Nadeem, M.; Rakha, A.; Shakoor, S.; Shehzad, A.; Khan, M.R. Structural Characterization of Oat Bran (1→3), (1→4)-β-d-Glucans by Lichenase Hydrolysis Through High-Performance Anion Exchange Chromatography with Pulsed Amperometric Detection. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 19, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maltini, E.; Torreggiani, D.; Venir, E.; Bertolo, G. Water activity and the preservation of plant foods. Food Chem. 2003, 82, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrauri, J.A.; Rupérez, P.; Saura-Calixto, F. Mango peel fibres with antioxidant activity. Z. Für Lebensm. Und-Forsch. A 1997, 205, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, L.N.; Liu, Y.B.; Li, B.H. Lycopene exerts anti-inflammatory effect to inhibit prostate cancer progression. Asian J. Androl. 2018, 21, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anang, D.A.; Pobee, R.A.; Antwi, E.; Obeng, E.M.; Atter, A.; Ayittey, F.K.; Boateng, J.T. Nutritional, microbial and sensory attributes of bread fortified with defatted watermelon seed flour. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.; Damgaard, T.W.; Sorensen, A.D.; Raben, A.; Lindelov, T.S.; Thomsen, A.D.; Bjergegaard, C.; Sorensen, H.; Astrup, A.; Tetens, I. Whole flaxseeds but not sunflower seeds in rye bread reduce apparent digestibility of fat in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ribas-Agusti, A.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Elez-Martinez, P. Food processing strategies to enhance phenolic compounds bioaccessibility and bioavailability in plant-based foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 58, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skenderidis, P.; Mitsagga, C.; Giavasis, I.; Petrotos, K.; Lampakis, D.; Leontopoulos, S.; Hadjichristodoulou, C.; Tsakalof, A. The in vitro antimicrobial activity assessment of ultrasound assisted Lycium barbarum fruit extracts and pomegranate fruit peels. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 2017–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantuono, A.; Ferracane, R.; Vitaglione, P. Potential bioaccessibility and functionality of polyphenols and cynaropicrin from breads enriched with artichoke stem. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longoria-García, S.; Cruz-Hernández, M.A.; Flores-Verástegui, M.I.M.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Montañez-Sáenz, J.C.; Belmares-Cerda, R.E. Potential functional bakery products as delivery systems for prebiotics and probiotics health enhancers. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananingsih, V.K.; Gao, J.; Zhou, W. Impact of green tea extract and fungal alpha-amylase on dough proofing and steaming. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2013, 6, 3400–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pathak, D.; Majumdar, J.; Raychaudhuri, U.; Chakraborty, R. Study on enrichment of whole wheat bread quality with the incorporation of tropical fruit by-product. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, R.C.; Li, C.Y.; Shiau, S.Y. Physico-chemical and sensory properties of bread enriched with lemon pomace fiber. Czech J. Food Sci. 2015, 33, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoye, C., Jr.; Ross, C.F. Total phenolic content, consumer acceptance, and instrumental analysis of bread made with grape seed flour. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, S428–S436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Ma, J.; Cheng, K.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, M. The effects of grape seed extract fortification on the antioxidant activity and quality attributes of bread. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, H.; Şen, H. Effects of pomegranate seed flour on dough rheology and bread quality. CYTA J. Food 2017, 15, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Sivam, A.S.; Cooney, J.; Zhou, J.; Perera, C.O.; Waterhouse, G.I.N. Effects of added fruit polyphenols and pectin on the properties of finished breads revealed by HPLC/LC-MS and size-exclusion HPLC. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 3047–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivam, A.S.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Quek, S.Y.; Perera, C.O. Physicochemical properties of bread dough and finished bread with added pectin fiber and phenolic antioxidants. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, Z.E.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. Development of fibre-enriched wheat breads: Impact of recovered agroindustrial by-products on physicochemical properties of dough and bread characteristics. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bchir, B.; Rabetafika, H.N.; Paquot, M.; Blecker, C. Effect of pear, apple and date fibres from cooked fruit by-products on dough performance and bread quality. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2014, 7, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, I.; Guraya, H.; Champagne, E. The functional effectiveness of reprocessed rice bran as an ingredient in bakery products. Nahrung/Food 2002, 46, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hamid, A.; Luan, Y.S. Functional properties of dietary fibre prepared from defatted rice bran. Food Chem. 2000, 68, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand, E.; Razavi, S.; Yarmand, M.; Morovatpour, M. Development of Iranian rice-bran sourdough breads: Physicochemical, microbiological and sensorial characterisation during the storage period. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crop. Foods 2015, 7, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.; O’Flaherty, J.; Brunton, N.; Arendt, E.; Gallagher, E. The utilisation of barley middlings to add value and health benefits to white breads. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, I.; Măcelaru, I.; Aprodu, I. Bioprocessing for improving the rheological properties of dough and quality of the wheat bread supplemented with oat bran. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e13112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemdane, S.; Langenaeken, N.A.; Jacobs, P.J.; Verspreet, J.; Delcour, J.A.; Courtin, C.M. Study of the intrinsic properties of wheat bran and pearlings obtained by sequential debranning and their role in bran-enriched bread making. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 71, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, M.H.; Bilgicli, N.; Elgün, A.; Demir, M.K. Effects of buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentummoench) milling products, transglutaminase and sodium stearoyl-2-lactylate on bread properties. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2013, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Estrada, B.A.; Lazo-Vélez, M.A.; Nava-Valdez, Y.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O. Improvement of dietary fiber, ferulic acid and calcium contents in pan bread enriched with nejayote food additive from white maize (Zea mays). J. Cereal Sci. 2014, 60, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojić, M.; Dapčević Hadnađev, T.; Hadnađev, M.; Rakita, S.; Brlek, T. Bread supplementation with hemp seed cake: A by-product of hemp oil processing. J. Food Qual. 2015, 38, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salgado, J.M.; Rodrigues, B.S.; Donado-Pestana, C.M.; dos Santos Dias, C.T.; Morzelle, M.C. Cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) peel as potential source of dietary fiber and phytochemicals in whole-bread preparations. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2011, 66, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elleuch, M.; Bedigian, D.; Roiseux, O.; Besbes, S.; Blecker, C.; Attia, H. Dietary fibre and fibre-rich by-products of food processing: Characterisation, technological functionality and commercial applications: A review. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn-Stoll, U. Pectin-water interactions in foods—From powder to gel. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 78, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Jaiswal, A.K. Exploitation of Food Industry Waste for High-Value Products. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axel, C.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Mold spoilage of bread and its biopreservation: A review of current strategies for bread shelf life extension. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3528–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, I.; Cairncross, C.; Sturny, A.; Rush, E. Towards improving the nutrition and health of the aged: The role of sprouted grains and encapsulation of bioactive compounds in functional bread—A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 54, 1435–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Ma, S.; Li, L.; Zheng, X.; Wang, X. Rheological properties of gluten and gluten-starch model doughs containing wheat bran dietary fibre. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 2650–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.; Mitra, A.; Pal, K.; Rousseau, D. Effect of flaxseed gum on reduction of blood glucose and cholesterol in type 2 diabetic patients. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.; Savorani, F.; Christensen, S.; Engelsen, S.B.; Bugel, S.; Toubro, S.; Tetens, I.; Astrup, A. Flaxseed dietary fibers suppress postprandial lipemia and appetite sensation in young men. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altunkaya, A.; Hedegaard, R.V.; Brimer, L.; Gokmen, V.; Skibsted, L.H. Antioxidant capacity versus chemical safety of wheat bread enriched with pomegranate peel powder. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Asta, M.; Bresciani, L.; Calani, L.; Cossu, M.; Martini, D.; Melegari, C.; Del Rio, D.; Pellegrini, N.; Brighenti, F.; Scazzina, F. In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Acids from a Commercial Aleurone-Enriched Bread Compared to a Whole Grain Bread. Nutrients 2016, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koistinen, V.M.; Katina, K.; Nordlund, E.; Poutanen, K.; Hanhineva, K. Changes in the phytochemical profile of rye bran induced by enzymatic bioprocessing and sourdough fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koistinen, V.M.; Nordlund, E.; Katina, K.; Mattila, I.; Poutanen, K.; Hanhineva, K.; Aura, A.M. Effect of bioprocessing on the in vitro colonic microbial metabolism of phenolic acids from rye bran fortified breads. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 1854–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sho, C.; Kurata, R.; Okuno, H.; Takase, Y.; Yoshimoto, M. Sweet potato-derived shochu distillery by-products supernatants. Nippon Shokuhin Kagaku Kogaku Kaishi 2008, 55, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelino, D.; Cossu, M.; Marti, A.; Zanoletti, M.; Chiavaroli, L.; Brighenti, F.; Del Rio, D.; Martini, D. Bioaccessibility and bioavailability of phenolic compounds in bread: A review. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2368–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Dokkum, W.; Wesstra, A.; Schippers, F.A. Physiological effects of fibre-rich types of bread. Br. J. Nutr. 1982, 47, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Dokkum, W.; Pikaar, N.A.; Thissen, J.T.N.M. Physiological effects of fibre-rich types of bread. Br. J. Nutr. 1983, 50, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bresciani, L.; Scazzina, F.; Leonardi, R.; Dall’Aglio, E.; Newell, M.; Dall’Asta, M.; Melegari, C.; Ray, S.; Brighenti, F.; Del Rio, D. Bioavailability and metabolism of phenolic compounds from wholegrain wheat and aleurone-rich wheat bread. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2343–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.X.; Walker, K.Z.; Muir, J.G.; Mascara, T.; O’Dea, K. Arabinoxylan fiber, a byproduct of wheat flour processing, reduces the postprandial glucose response in normoglycemic subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanhineva, K.; Keski-Rahkonen, P.; Lappi, J.; Katina, K.; Pekkinen, J.; Savolainen, O.; Timonen, O.; Paananen, J.; Mykkanen, H.; Poutanen, K. The postprandial plasma rye fingerprint includes benzoxazinoid-derived phenylacetamide sulfates. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Juntunen, K.S.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Poutanen, K.S.; Niskanen, L.K.; Mykkänen, H.M. High-fiber rye bread and insulin secretion and sensitivity in healthy postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abraham, A.; Kattoor, A.J.; Saldeen, T.; Mehta, J.L. Vitamin E and its anticancer effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, G. High dietary choline and betaine intake is associated with low insulin resistance in the Newfoundland population. Nutrition 2017, 33, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.H.; Chen, T.Y.; Lu, R.W.; Chen, S.T.; Chang, C.C. Benzoxazinoids from Scoparia dulcis (sweet broomweed) with antiproliferative activity against the DU-145 human prostate cancer cell line. Phytochemistry 2012, 83, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Functional Ingredients | Substitution Levels | Treatment of Plant-Based by-Products | Favourable Substitution Level | Effects on Qualities of Bread | Quantitative Variations from the Control Measures | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables and fruit by-products utilization | ||||||

| Tomato by-product | 6 and 10% | drying at 60 ℃ | N/A | ↓specific volume. | 6% substitution-specific volume ↓(6.6%), 10% substitution-specific volume ↓(7.1%) | [17] |

| Artichoke (Cynarascolymus L.) by-product | 3, 6, 9 and 12% | lyophilized and milled | 3% | ↓loaf volume except for the 3% substitution, ↑crumb hardness and ↓crumb L* values | 3% substitution-specific volume (0%), crumb hardness ↑(27.2%), L* ↓(12.8%), 6% substitution-specific volume ↓(~8%), crumb hardness ↑(39.9%), L* ↓(31.1%),9% substitution-specific volume ↓(~8%), crumb hardness ↑(58.9%), L* ↓(36%) and 12% substitution-specific volume ↓(~32%), crumb hardness ↑(78%) and L* ↓(41.5%) | [16] |

| Raw mango peel powder | 1, 3 and 5% | blanching, wet milling, pulping, drying and milling | ↓specific volume and whiteness index. ↑loaf density | 1% substitution-specific volume ↓(9.7%), whiteness index ↓(5%), loaf density ↑(9.8%), 3% substitution-specific volume ↓(17.1%), whiteness index ↓(8.9%) and loaf density ↑(16%), 5% substitution-specific volume ↓(21.9%), whiteness index (12%) and loaf density ↑(23%). | [66] | |

| Lemon pomace fibre | 3, 6 and 9% | N/A | 3% | ↓specific volume and ↑crumb hardness | 3% substitution- specific volume ↓(~33%), crumb hardness ↑(~50%), 6% substitution- specific volume ↓(~44%), crumb hardness ↑(~68.8%) and 9% substitution- specific volume ↓(~50%), crumb hardness ↑(~81.8%). | [67] |

| Pineapple pomace fibre | 5 and 10% | N/A | 5% | ↓specific volume. ↑crumb hardness except for 5% substitution. ↓crumb L* values. | 5% substitution-specific volume ↓(6.5%), crumb hardness ↓(10.9%), crumb L*↓(2%) and 10% substitution-specific volume ↓(34.8%), crumb hardness (57.3%) and crumb L* ↓(3.6%). | [4] |

| Grape pomace flour from Merlot and Zelen cultivars | 6, 10 and 15% | drying and milling | 6% | ↓specific volume, ↑crumb hardness except for the 3% Merlot, Zelen and 10% Zelen grape pomace flour substitution and ↓L* values | 6% substitution (Merlot grape)-specific volume ↓(~7.1%%), hardness ↓(~12.3), L* ↓(35.5%), (Zelen grape)-specific volume ↓(~7.1%), crumb hardness ↓(~29%), L* ↓(29.2%), 10% substitution (Merlot grape)-specific volume ↓(~9%), crumb hardness ↑(~11.5%), L* ↓(40.3%), (Zelen grape)-specific volume (~9%), crumb hardness ↓(~5.8%), L* (33.3%), 15% substitution (Merlot grape)-specific volume ↓(~8.6), crumb hardness ↑(~18.8%), L* ↓(46.7%), (Zelen grape)-specific volume ↓(~17.8%), crumb hardness (~1.4%), L* (~37.5%). | [2] |

| Grape seed flour (GSF) | 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 g GSF/100 g wheat flour | N/A | 2.5–5% | ↓loaf volume, ↑crumb hardness and ↓loaf brightness | 2.5 g GSF/100 g wheat flour substitution-loaf volume ↓(7%), crumb hardness ↑(7.6%), 5 g GSF/100 g wheat flour substitution-loaf volume ↓(12.8%), crumb hardness ↑(14.2%), 7.5 g GSF/100 g wheat flour substitution-loaf volume ↓(18.4%), crumb hardness ↑(34.8%), 10 g GSF/100 g wheat flour substitution-loaf volume (26.1%) and crumb hardness ↑(51.4%) | [68] |

| Grape seed extract | 300 mg, 600 mg and 1 g | N/A | 300 mg, 600 mg and 1 g | ↑crumb hardness with the exception of the 300 mg-substituted bread. ↓ L* values | 300 mg substitution-crumb hardness ↓(~3.75), L* ↓(8.8%), 600 mg substitution-crumb hardness ↓(1.2%), L* ↓(12%), and 1 g substitution ↓(1.2%) and L*↓(12.9%) | [69] |

| Pomegranate seed flour | 5, 7.5 and 10% | drying and milling | ↓loaf volume and L* values. ↑ hardness | 5% substitution- loaf volume ↓(21.9%), L* ↓(23.7%), crumb hardness ↑(35.8%), 7.5% substitution- loaf volume ↓(29.6%),L* ↓(27.2%), crumb hardness ↑(50%) and 10% substitution-loaf volume ↓(36.4%), L* ↓(30.3%), crumb hardness ↑(53.1%). | [70] | |

| Kiwifruit polyphenol extract (KPE), blackcurrant polyphenol extract (BPE) and apple polyphenol extract (APE) with high methoxy pectin (HM) | (3% HM pectin+3% KPE), (3% HM pectin+3% BPE) and (3% HM pectin+3% APE) | N/A | ↓loaf volume and ↑crumb hardness | (3% HM pectin+3% KPE) substitution-specific volume ↓(23.5%), crumb hardness ↑(26.7%), (3% HM pectin+3% BPE) substitution- specific volume ↓(12.1%), crumb hardness ↑(35.3%) and (3% HM pectin+3% APE) substitution- specific volume ↓(26.3%) and crumb hardness ↑(71.4%). | [71] | |

| Apple pectin | Apple pectin(s) of low molecular weight and high molecular weight at a ratio of 1:1, at concentrations of 3 or 6% w/w), in the absence or presence of added kiwifruit phenolic extract, apple phenolic extract or blackcurrant phenolic extract (at 3% w/w). | 3 and 6% | 3% | ↓loaf volume and L* values | 3% apple pectin substitution-loaf volume ↓(2.2%), L* ↓(9.2%), 6% apple pectin substitution- loaf volume ↓(24%), L* ↓(12.2%), 3% pectin and 3% kiwifruit phenolic extract substitution-loaf volume ↓(28%), L* ↓(18.6), 3% apple pectin and 3% apple phenolic extract substitution-loaf volume ↓(33.5%), L* ↓(21.3%) and 3% apple pectin and 3% blackcurrant phenolic extract substitution-loaf volume ↓(12%) and L* ↓(31.8%) | [72] |

| Orange extract powder (OE), pomegranate extract powder (PE), elderberry extract powder (EE) and yeast extract powder (YE) | 4% EE, 36% EE, 4% OE, 8% OE, 4% PE, 16% PE and 4% YE | OE = Hot water blanching of orange peel, oven drying, ethanol extraction, oven drying and milling. PE = Hot water blanching, oven drying and milling. EE = Ethanol extraction, oven drying and milling YE = Autolysis, Base and acid extractions, lyophilizing and milling | 4% | ↑loaf volume for 4% EE, 4% OE and 4% YE. Crumb hardness for 4% EE, 36% EE, 4% OE and 4% YE showed no significant difference compared to the control but was significantly ↓ for 4% EE | 4% elderberry extract substitution-specific volume ↑(15.8%), crumb hardness ↓(40.4%), 36% substitution- specific volume ↓(16.6%), crumb hardness ↑(9%), orange extract: 4% substitution-specific volume ↑(9.7%), crumb hardness ↓(15.5%), 8% substitution-specific volume (10.2%), pomegranate extract: 4% substitution- specific volume ↓(9.1%), crumb hardness ↑(20.9%), 16% substitution-specific volume ↓(37.4%), crumb hardness ↑(69%), yeast extract: 4% substitution-specific volume (1.1%) and crumb hardness ↓(4.5%). | [73] |

| Flesh fibre concentrate from apple, pear, and date pomaces | 2% of fibre | cooked fruit by-products | 2% | favourable effect on specific volume of bread loaves and on the crumb and crust texture | Apple fibre: 2% substitution-specific volume ↓(3.4%), pear fibre: 2% substitution- specific volume ↓(6.9%) and date fibre: 2% substitution-specific volume ↓(6.9%). | [74] |

| Grains/cereals and pseudocereal by-products | ||||||

| Processed full-fat (FFRB) and defatted (DFRB) bran from long, medium and short grain | 10 and 20% | freezing rice bran, autoclave stabilization, drying, ricebran slurry preparation, drum-drying and defatting. | 10% FFRB | ↓specific volume with the exception of the 10% FFRB from long grain. ↑crumb hardness for DFRB bread than for FFRB. | Full fat rice bran-10% substitution: long grain rice bran- specific volume ↑(1.3%), medium grain rice bran- specific volume ↓(0.2%), short grain rice bran-specific volume ↓(1.1%), Defatted rice bran-10% substitution-long grain rice bran-specific volume ↓(10.7%), medium grain rice bran- specific volume ↓(3.9%), short grain rice bran-specific volume ↓(5.7%), Full fat rice bran-20% substitution-long grain rice bran- specific volume ↓(7.9%), medium grain rice bran-specific volume ↓(4.6%), short grain rice bran- specific volume ↓(13.4%), defatted rice bran-20% substitution-long grain rice bran- specific volume ↓(18.6%), medium grain rice bran- specific volume ↓(16.2%), short grain rice bran-specific volume ↓(19.7%). | [75] |

| Dietary fibre from defatted rice bran | 5 and 10% | defatting, gelatinization, digestion with protease, incubation with amyloglucosidase, precipitation of soluble dietary fibre using alcohol, filtration and oven-drying | ↑crumb hardness and ↓loaf volume | 5% substitution-loaf volume ↓(22.9%), crumb hardness ↑(47.6%) and 10% substitution-loaf volume ↓(37.8%), hardness ↑(79.6%). | [76] | |

| Rice bran | 10% | fermentation using L. plantarum, L. mesenteroides and L. delbrueckii | 10% with L. mesenteroides | ↓crumb hardness for sourdough breads. ↑loaf volume for bread from sourdoughs fermented by L. mesenteroides | N/A | [77] |

| Middling fraction (M) of wholegrain (WM) and pearled (PM) barley | 15, 30, 45 and 60% | pearling | 30% WM and 15% PM | loaf volume not affected for 30% WM and 15% PM-substituted breads significantly. ↑hardness for barley bread | 15% barley middlings-loaf volume-whole ↓(~4.1%) and pearled ↓(~4.8%), 30% middlings-loaf volume-whole ↓(6.2%) and pearled ↓(~11.56%), 45% middlings-loaf volume-whole ↓(~17%) and pearled ↓(~25.2%), 60% middlings-loaf volume- whole ↓(~31.5%) and pearled (~31.5%). | [78] |

| Oat bran | 10, 20 and 30% | enzymatic bioprocessing with xylanase and sourdough fermentation | xylanase and sourdough addition increased the bread specific volume and reduced crumb hardness | Oat bran: 10% substitution-specific volume ↓(~3.4%), crumb hardness ↑(~10%), 20% substitution-specific volume ↓(~13.8%), crumb hardness ↑(25.6%), 30% substitution-specific volume ↓(~24.1%), crumb hardness ↑(~35.7%), sourdough + oat bran, 10% substitution-specific volume (~8.6%), crumb hardness ↑(~25%), 20% substitution-specific volume ↓(~16.7%), crumb hardness (~5.6%), 30% substitution-specific volume ↓(~14.3%) and crumb hardness ↑(~55.6%). | [79] | |

| Wheat bran | Sequential pearling of wheat kernels to 3, 6, 9 and 12% by weight | thermal treatment and native | ↓bread volume and ↑crumb hardness | Ground bran-hardness ↑(55.2%), pearlings,0–3%, crumb hardness ↑(70.9%), heat-treated pearlings,0–3%, crumb hardness ↑(65%), pearlings, 3–6%, crumb hardness ↑(64.4%), pearlings, 6–9%, crumb hardness ↑(52.6%), pearlings, 6–12%, crumb hardness ↑(49%) | [80] | |

| Wheat bran and germ mixture | 15% (w/w) of fermented (and unfermented) milling by-products | fermentation | 15% | ↑specific volume and ↓crumb hardness | Specific volume ↑(8.9) and crumb hardness ↓(15.8%) | [43] |

| Buckwheat (Fagopyrum Esculentum Moench) bran | 20% | enzymatic treatment with transglutaminase (TG) and sodium stearoyl-2-lactylate (SSL) | 20% with SSL + TG (0.5% + 0.4%) | ↓bread volume for buckwheat bran bread. Combination of SSL + TG to the bran significantly improved bread crumb lightness, volume and crumb softness | Buckwheat bran (20% substitution without any additive)-specific volume ↓(38.3%), crumb hardness ↑(51%), crumb L* (32.1%) | [81] |

| Rootlets | 5, 10, 15 and 20% | fermentation | 5% | ↓specific volume except the 5% substitution and ↑crumb hardness | 5% substitution-specific volume ↑(6.9%), crumb hardness ↑(34%), 10% substitution- specific volume ↑(9%), crumb hardness ↑(52.7%), 15% substitution-specific volume ↓(21.5%), crumb hardness ↑(67.5%) and 20% substitution-specific volume ↓(31.3%), crumb hardness ↑(68.8%) | [13] |

| Brewers spent grain | 5, 10, 15 and 20% | fermentation using Lactobacillus plantarum FST 1.7 | 5% | ↓specific volume. ↑crumb hardness with the exception of 5% fermented brewers spent grain | 5% substitution-specific volume ↓(8.7%), crumb hardness ↓(16.1%), 10% substitution-specific volume ↓(12.6%), crumb hardness ↑(28.7%), 15% substitution-specific volume ↓(22.4%), crumb hardness ↑(56.4%), 20% substitution-specific volume ↓(28%) and crumb hardness ↑(69.5%) | [14] |

| Nejayote solids | 3, 6 and 9% | vacuum filtration, freezing and lyophilizing | 3 and 6% | ↓loaf volume and ↓whiteness (L*) values. | 3% substitution-loaf volume ↓(2%), L* ↓(2.5%),6% substitution-loaf volume ↓(5.1%), L* ↓(6.5%), and 9% substitution-loaf volume ↓(9.5%), L* ↓(7.4) | [82] |

| Oilseed and bean by-products | ||||||

| Naked pumpkin seed (PuC), sunflower seed (SC), yellow linseed (LC), and walnut (WnC) cakes | 5 and 10% | N/A | ↑dough stability with walnut cake enrichment WnC | N/A | [8] | |

| Hemp seed cake | 5,10 and 20% | N/A | 5 and 10% | ↓specific volume, ↑crumb hardness and ↓ b* values | 5% substitution-specific volume ↓(18%), hardness ↑(31.2) and crumb b* value ↓(12.8), 10% substitution, specific volume ↓(41%), hardness ↑(56%) and crumb b* value ↓(22.5%) and 20% substitution, specific volume ↓(45.9%), hardness ↑(71.3%) and crumb b* ↓(39.9%) | [83] |

| Flaxseed flour and marc | 5, 10, 15% | cakes from cold pressed flaxseed, milling and pulverisation | 5% | ↓specific volume | 5% substitution-flaxseed flour- specific volume ↓(6.3%) and crumb hardness ↑(6.8%), flaxseed marc- specific volume ↓(4.6%), crumb hardness ↓(2.4%), 10% substitution- flaxseed flour- specific volume ↓(13%) and crumb hardness ↑(23%), flaxseed marc- specific volume ↓(13%), crumb hardness ↓(2.4%) and 15% substitution-flaxseed flour- specific volume ↓(18.6%), crumb hardness ↑(53.4%), flaxseed marc- specific volume ↓(18.2%), crumb hardness ↑(12.8%) | [7] |

| Cupuassu peel flour | 3, 6, and 9% cupuassu peel flour | separation of peel from pulp and seeds, cleaning in hypochlorite solution, freeze-drying and milling into powder. | N/A | ↑b* values of the bread crumb | 3% substitution-b* ↑(23.6%) 6% substitution- b* value (25.7%)- and 9% substitution- b* value (29.9%)) | [84] |

| Ingredients | Substitution Levels | Pre-Treatment | Findings | Acceptable Substitution | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits and vegetables by-products | |||||

| Fermented and unfermented citrus peels | 2, 4 and 6% | fermentation and thermal treatment with hot air at 100 and 150 °C. | ↑ acceptability for unfermented citrus peel flour-enriched bread | 4 and 6% unfermented citrus peels treated at with hot dry air at 150 and 100 °C respectively | [15] |

| Grape pomace flour | 6, 10 and 15% | drying and milling | ↑sand feeling in the mouth and was affected by the variety of grape used | N/A-Descriptive test | [2] |

| Grape seed flour | 2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10 g GSF/100 g wheat flour | N/A | ↓ratings in astringency and sweetness (≥7.5 g GSF/100 gHRS) substitution). | Up to 5 g GSF/100 g wheat flour | [68] |

| Lemon pomace fibre | 3, 6 and 9% | N/A | ↓ sensory values for flavour, texture, and overall acceptability (6 and 9%). | 3% | [67] |

| Pomegranate seed flour | 5, 7.5 and 10% | N/A | ↑fibre content and appealing organoleptic sensations for the 5% substitution | 5% | [70] |

| Pineapple pomace fibre (PPF) | 5 or 10% | N/A | ↓sensory liking score (10% substitution) | 5% | [4] |

| Grains/cereals, pseudocereals by-products | |||||

| Wheat bran and germ mixture | 15% (w/w) | fermentation | ↑protein scores, in-vitro protein digestibility, essential amino acid index and biological values (fermented wheat bran and germ mixture). ↑dietary fibre for enriched breads | N/A | [43] |

| Dietary fibre from defatted rice bran | 5 and 10% | defatting, gelatinization, digestion with protease, incubation with amyloglucosidase, precipitation of soluble dietary fibre using alcohol, filtration and oven-drying | ↑higher fibre (5 and 10% rice bran) | N/A | [76] |

| “Middling’’ fraction (M) of wholegrain (WM) and pearled (PM) barley | 15%, 30%, 45% and 60% | pearling | no significant difference was found in the acceptability of WM and PM breads | Up to 30% barley middling | [78] |

| Buckwheat (Fagopyrum Esculentum Moench) milling products | 20% | enzymatic treatment with transglutaminase (TG) and sodium stearoyl-2-lactylate (SSL) | ↓overall acceptability score for buckwheat bran-enriched bread. ↑fibre, protein, ash, mineral and fat contents for buckwheat bran enriched bread | [81] | |

| Rootlets | 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% | fermentation | ↑ liking of organoleptic attributes | 5% fermented rootlet | [13] |

| Brewers spent grain | 5, 10, 15 and 20% | fermentation using the lactic acid bacteria, Lactobacillus plantarum FST 1.7 | ↑ liking for bread enriched with brewers spent grain or fermented brewers spent grain (using the lactic acid bacteria, Lactobacillus plantarum FST 1.7) | 10% | [14] |

| Nejayote solids | 3, 6, 9% | vacuum filtration, freezing and lyophilizing | no adverse effect on the textural perception by consumers. | Up to 9% | [82] |

| Oilseed by-products | |||||

| Cake from from naked pumpkin seed (PuC), sunflower seed (SC), yellow linseed (LC), and walnut (WnC) | 5% and 10% | N/A | ↑brown appearancefor WnC (walnut) | 5% SC | [8] |

| Flaxseed flour and marc | 5, 10 and 15% | milling and pulverization | ↑protein, ash and total dietary fibre | 5% | [7] |

| Food by-Product | Type of Study | Sample Size | Amount of Bioactive Consumed | Findings | Quantitative Changes Induced by Food-by Product Substitution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black currant seed press | pre-post study design | 36 (Healthy adults) | 20 g black currant by-product/d | ↑ serum α-, γ- and ↓β- tocopherol concentration. | α tocopherol ↑(1.7%) β tocopherol ↓(5.3%) γ tocopherol ↑(20.8%) (change from baseline) | [21] |

| Aleurone fraction of wheat bran | single-blind, randomised, cross-over study | 15 (urine sampling periods) and 5 (blood sampling periods) (Healthy adults) | approx. 94 (AB-94) and 190 g (AB-190) aleurone-rich breads containing approx. 43 and 87 mg of total ferulic acid respectively | ↑bioavailability of ferulic acid | % bioavailability-control-4%, AB-94-~8% and AB-190~5% | [101] |

| Arabinoxylan-oligosaccharides from rye bran treated with thermophilic endoxylanase | randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled cross-over study | 40 (Healthy adults) | 2.20 g arabinoxylan | ↑faecal butyrate and acetate and ↓propionate concentration | butyrate ↑(29.4%), acetate ↑(17.2%), propionate ↓(1.7%) and total acetate, propionate and butyrate ↑(15.7%) (changes from baseline) | [25] |

| In situ-produced arabinoxylan from rye bran | randomised, double-blind, controlled, cross-over study | 27 (Healthy adults) | 1.90% of dry matter | ↑ faecal total short chain fatty acids concentration particularly butyric acid | acetic acid ↑(27.9%), propionic acid ↑(28.8%), butyric acid ↑(41.5%) and total short chain fatty acids ↑(35.7%) | [26] |

| Arabinoxylan fibre (AX) | randomised, crossover design | 14 (Healthy adults) | 6 and 12 g AX fibre | ↓peak postprandial glucose concentration | incremental area under the glucose curve: 6 g AX- ↓(~23.8%) and 12 g AX- ↓(~42.9%) and incremental area under insulin curve: 6 g AX- ↓(~19.6%) and 12 g AX ↓(~42.9%) | [102] |

| Wheat bran extract rich in arabinoxylan oligosaccharides (AXOS) | randomised cross-over study | 19 (Healthy adults) | 18.4 AXOS g/portion | ↓glycaemic response. ↑acetate, propionate, butyrate and total short chain fatty acid concentration in the morning. | change in glucose incremental area under the curve (0–120 min) ↓(15.8%) and ↓(18.5%) for (0–180 min) when compared to control bread | [20] |

| Concentrated arabinoxylan from wheat | acute, randomised cross-over intervention study | 15 (Adults with Metabolic syndrome) | 7 g of arabinoxylan | ↑satiety sensation | incremental area under the curve for satiety change ↑(26%), | [23] |

| Wheat bran and aleurone | randomized controlled, cross-over | 14 (Healthy adults) | 50 g each | ↑postprandial plasma betaine concentrations with consumption of minimally processed wheat bran | postprandial betaine concentration ↑(49%) | [19] |

| Rye bran | randomized crossover | 12 (Healthy adults) | In a flour basis of 65% white wheat flour and 35% bran, whereas the commercial sourdough rye bread contained 16% bran | ↑sulfonated phenylacetamides compounds in blood plasma specifically hydroxy-N-(2-hydroxyphenyl) acetamide and N-(2-hydroxyphenyl) acetamide | N/A | [103] |

| Rye bran | randomised crossover trial | 20 (Healthy adults) | The portions of rye breads weighed 24.1–28.1 g and those of wheat breads, 20.8–25.0 g. A minimum of 4–5 portions of the test breads had to be eaten each day. | ↑insulin secretion | plasma glucose ↑(0.7%) and plasma insulin ↓(6%)- | [104] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amoah, I.; Taarji, N.; Johnson, P.-N.T.; Barrett, J.; Cairncross, C.; Rush, E. Plant-Based Food By-Products: Prospects for Valorisation in Functional Bread Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187785

Amoah I, Taarji N, Johnson P-NT, Barrett J, Cairncross C, Rush E. Plant-Based Food By-Products: Prospects for Valorisation in Functional Bread Development. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187785

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmoah, Isaac, Noamane Taarji, Paa-Nii T. Johnson, Jonathan Barrett, Carolyn Cairncross, and Elaine Rush. 2020. "Plant-Based Food By-Products: Prospects for Valorisation in Functional Bread Development" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187785

APA StyleAmoah, I., Taarji, N., Johnson, P.-N. T., Barrett, J., Cairncross, C., & Rush, E. (2020). Plant-Based Food By-Products: Prospects for Valorisation in Functional Bread Development. Sustainability, 12(18), 7785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187785