The Relationship of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness, Subjective Knowledge, and Purchase Intention on Carbon Label Products—A Case Study of Carbon-Labeled Packaged Tea Products in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

2.1. Sampling and Data Collection

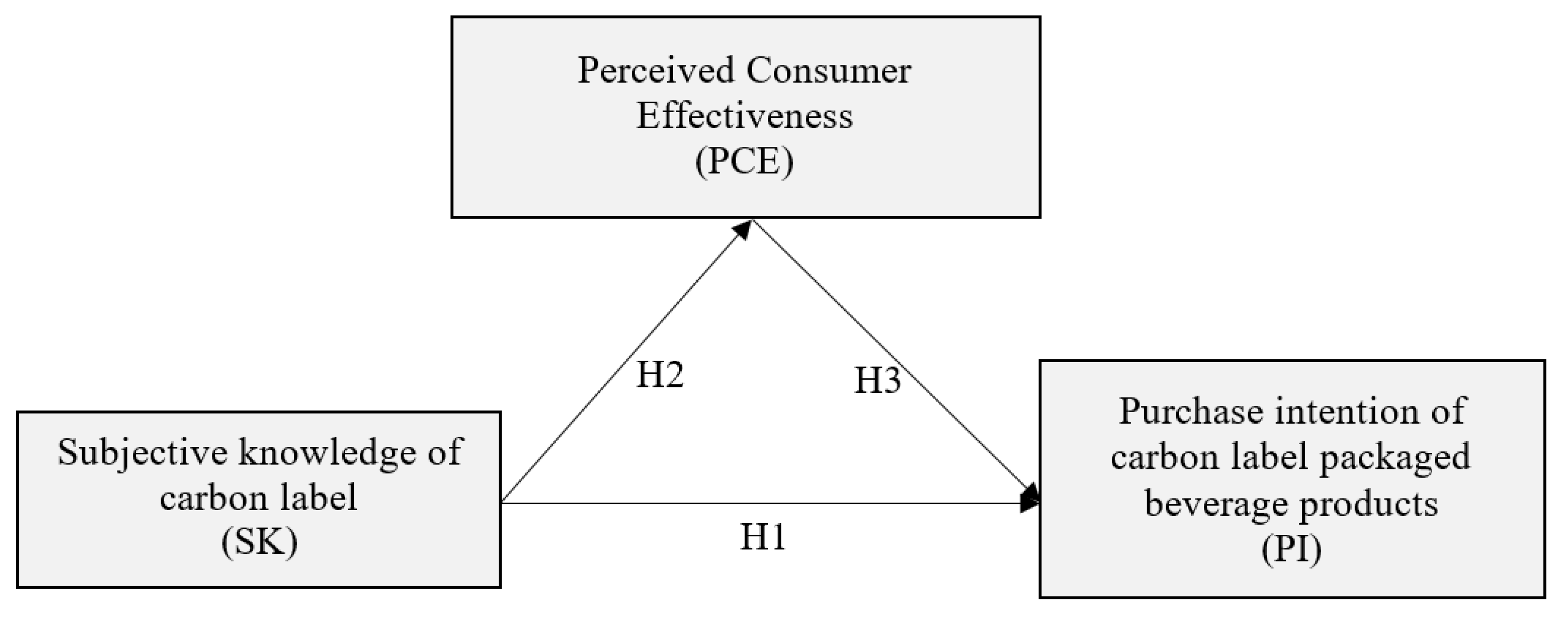

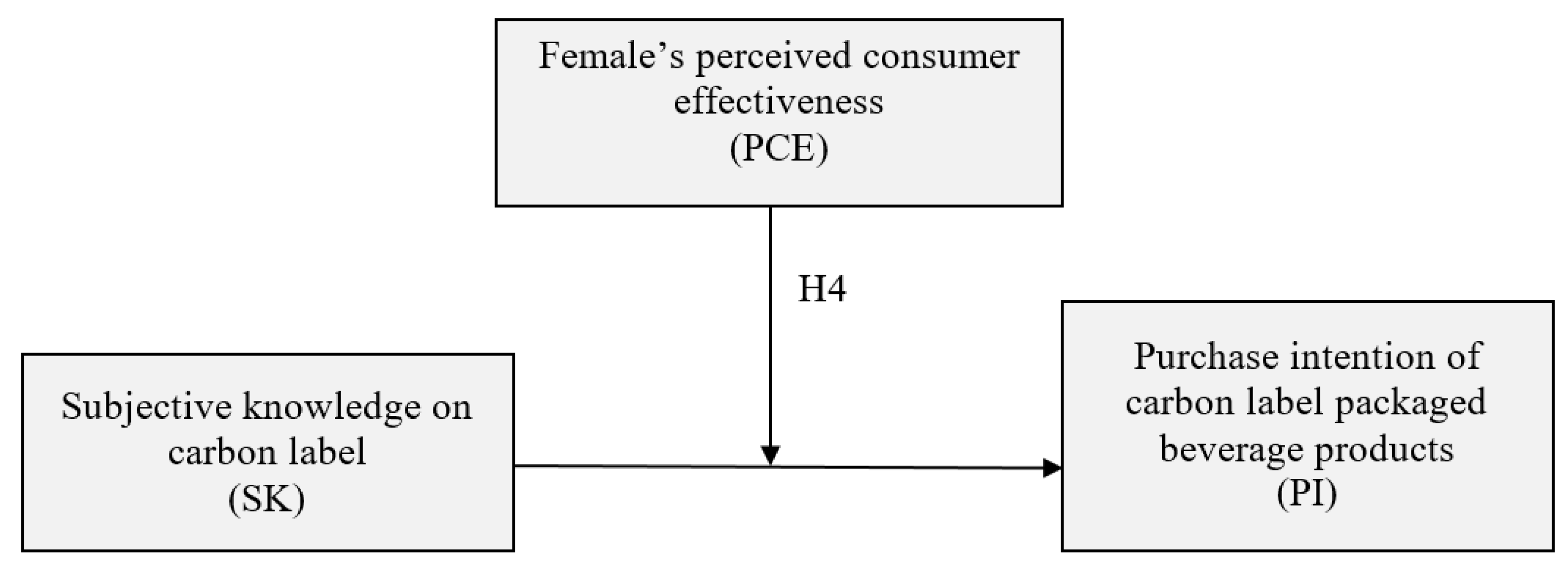

2.2. Research Hypotheses

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Result

3.2. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karling, H.M. Global Climate Change; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood, N.; Cohen, J. Greenhouse Gases and Society. Available online: http://umich.edu/~gs265/.../greenhouse.htm (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- McCarthy, J.J.; Canziani, O.F.; Leary, N.A.; Dokken, D.J.; White, K.S. (Eds.) Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Vol. 2); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hartikainen, H.; Roininen, T.; Katajajuuri, J.M.; Pulkkinen, H. Finnish consumer perceptions of carbon footprints and carbon labelling of food products. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, T.; Minx, J. A definition of ‘carbon footprint’. Ecol. Econ. Res. Trends 2008, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- East, A.J. What is a carbon footprint? An overview of definitions and methodologies. In Vegetable Industry Carbon Footprint Scoping Study—Discussion Papers and Workshop, 26 September 2008; Horticulture Australia Ltd.: North Sydney, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kasterine, A. Counting carbon in exports: Carbon footprinting initiatives and what they mean for exporters in developing countries. Int. Trade Forum 2010, 1, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Q.; Su, B. A review of carbon labeling: Standards, implementation, and impact. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Nielsen, K.S. A better carbon footprint label. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 125, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewmake, S.; Okrent, A.; Thabrew, L.; Vandenbergh, M. Predicting consumer demand responses to carbon labels. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.A.; Vandenbergh, M.P. The potential role of carbon labeling in a green economy. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, S53–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Inman, J.J.; Ross, W.T. Carbon Footprints in the Sand: Marketing in the Age of Sustainability. Cust. Needs Solut. 2014, 1, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swallow, L.; Furniss, J. Green business: Reducing carbon footprint cuts costs and provides opportunities. Mont. Bus. Q. 2011, 49, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwan Environmental Protection Agency. Taiwan Product Carbon Footprint. 2015. Available online: https://cfp.epa.gov.tw/EN/Product/Index (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Levy, A.; Orion, N.; Leshem, Y. Variables that influence the environmental behavior of adults. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 24, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, A.O.; Grebitus, C.; Steiner, B.; Veeman, M. How does consumer knowledge affect environmentally sustainable choices? Evidence from a cross-country latent class analysis of food labels. Appetite 2016, 106, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorman, C.; Diehl, K.; Brinberg, D.; Kidwell, B. Subjective knowledge, search locations, and consumer choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.W.; Fang, Y.S.; Cai, M.F. Discussion on the willingness to consume green products: The effect of the environmental protection label. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 14, 257–280. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.K.; He, J.J. The impact of carbon labeling on consumers’ green purchase intention: Are carbon labels useful? J. Mark. Sci. 2014, 10, 1–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors? The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, I.E.; Corbin, R.M. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Faith in Others as Moderators of Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.H.; Gao, Q.; Wu, Y.P.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.D. What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from Qingdao. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Wiener, J.L.; Cobb-Walgren, C. The Role of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness in Motivating Environmentally Conscious Behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, S.C.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, E.Y. The Role of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Motivational Attitude on Socially Responsible Purchasing Behavior in South Korea. J. Glob. Mark. 2012, 25, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Understanding green purchase: The influence of collectivism, personal values and environmental attitudes, and the moderating effect of perceived consumer effectiveness. Seoul J. Bus. 2011, 17, 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.Z. Joint Analysis to Explore the Impact of Carbon Labeling on Consumer Purchasing Decisions. Master’s Thesis, National Central University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.R. 2011 TOP5000 Enterprise Industry Observation and Prospects-Beverage Industry, 2012. Available online: http://www.credit.com.tw/happiness/img/%E9%A3%9F%E5%93%81%E6%A5%AD.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Lynch, N.E. Gendered applications of the carbon footprint: The use of carbon management tools to highlight the effect of gender on sustainable lifestyles. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 8, 297–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. Research Methods in Social Science; Cengange Learning: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vocino, A.; Polonsky, M.J. The influence of eco-label knowledge and trust on pro-environmental consumer behaviour in an emerging market. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, A.; Wheeler, M. Reducing householders’ grocery carbon emissions: Carbon literacy and carbon label preferences. Australas. Mark. J. 2013, 21, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.H. The role of animation in the consumer attitude formation: Exploring its implications in the tripartite attitudinal model. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2011, 19, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. A psychometric evaluation of 4-point and 6-point Likert-type scales in relation to reliability and validity. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1994, 18, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, A.; Wada, Y.; Kamada, A.; Masuda, T.; Okamoto, M.; Goto, S.I.; Dan, I. Interactive effects of carbon footprint information and its accessibility on value and subjective qualities of food products. Appetite 2010, 55, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Muralidharan, S. What triggers young Millennials to purchase eco-friendly products? The interrelationships among knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness, and environmental concern. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röös, E.; Tjärnemo, H. Challenges of carbon labelling of food products: A consumer research perspective. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 982–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G.; van Koppen, C.S.A.; Janssen, A.M.; Hendriksen, A.; Kolfschoten, C.J. Consumer responses to the carbon labelling of food: A real life experiment in a canteen practice. Sociol. Rural. 2013, 53, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhong, S. Carbon labelling influences on consumers’ behavior: A system dynamics approach. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 51, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Long, R.; Chen, H. Empirical study of the willingness of consumers to purchase low-carbon products by considering carbon labels: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Geng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, X.; Xue, B. Consumers’ perception, purchase intention, and willingness to pay for carbon-labeled products: A case study of Chengdu in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Dendler, L.; Bleda, M. Carbon labelling of grocery products: Public perceptions and potential emissions reductions. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.G.; Lee, I.S. Importance-performance and willingness to purchase analyses of home meal replacement using eco-friendly food ingredients in undergraduates according to gender. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 44, 1873–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Garma, R.; Grau, S.L. Western consumers’ understanding of carbon offsets and its relationship to behavior. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2011, 23, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | KMO Test | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Knowledge (SK) | 0.85 | 1. | CL (carbon label) indicates saving energy and eliminating carbon. | 0.64 | 0.88 |

| 2. | Guiding manufacturer to reduce carbon content in products. | 0.70 | |||

| 3. | Reducing ecological damage. | 0.68 | |||

| 4. | CL can identify environmentally friendly products. | 0.75 | |||

| 5. | CL guides consumers in purchasing environmentally friendly products. | 0.70 | |||

| 6. | CL helps to choose products with low carbon. | 0.74 | |||

| 7. | Increasing satisfaction in purchasing environmentally friendly products. | 0.77 | |||

| 8. | CL indicates as trustworthy products. | 0.63 | |||

| 9. | Improve producers’ knowledge about carbon label. | 0.32 | |||

| Perceived consumer effectiveness (PCE) | 0.93 | 1. | Personal behavior causes environmental change. | 0.72 | 0.93 |

| 2. | I believe that I have ability to solve environmental problems. | 0.80 | |||

| 3. | Consumers’ behavior affects society. | 0.82 | |||

| 4. | Buying environmentally friendly products (such as low-carbon products) can protect the environment. | 0.78 | |||

| 5. | Energy saving and carbon reduction behavior can combat global warming. | 0.80 | |||

| 6. | When buying a product, it will affect environment or other consumers. | 0.70 | |||

| 7. | Personal remedial action is effective to solve pollution problems. | 0.80 | |||

| 8. | Your contribution influences on environmental problem solving. | 0.81 | |||

| 9. | You believe that your personal behavior can control things. | 0.50 | |||

| 10. | You are confident that your action positively affects the environment. | 0.46 | |||

| Purchase Intention (PI) | 0.90 | 1. | I have the possibility to buy packaged tea beverages with carbon labeling. | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| 2. | I will buy packaged tea beverages with low- carbon label. | 0.83 | |||

| 3. | I will spend more money to buy products with carbon labels. | 0.78 | |||

| 4. | I am interested to buy products with carbon label. | 0.70 | |||

| 5. | I have intention to buy packaged tea beverages with carbon labels. | 0.85 | |||

| 6. | Packaged tea beverages with carbon labels are my first consideration. | 0.80 | |||

| 7. | Based on the above points, I will purchase products with carbon labels in future. | 0.54 | |||

| Hypothesis | Variables | Categories | Categories | Total | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||||

| f | % | ||||||

| H1 | SK | Purchase intention (PI) | |||||

| high | (f) | 56 | 161 | 217 | 0.001 * | ||

| (%) | 25.8 | 74.2 | |||||

| low | (f) | 139 | 55 | 194 | |||

| (%) | 71.6 | 28.4 | |||||

| H2 | PCE | Subjective knowledge (SK) | |||||

| high | (f) | 57 | 161 | 218 | 0.001 * | ||

| (%) | 26.1 | 73.9 | |||||

| low | (f) | 137 | 56 | 193 | |||

| (%) | 71.0 | 29.0 | |||||

| H3 | PCE | Purchase intention (PI) | |||||

| high | (f) | 49 | 169 | 218 | 0.001 * | ||

| (%) | 22.5 | 77.5 | |||||

| low | (f) | 146 | 47 | 193 | |||

| (%) | 75.6 | 24.4 | |||||

| Model | Independent Variables | R Value | R2 | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F Test | Standardized Coefficient | t Test | ||||

| Model 1 | Subjective knowledge | 0.678 | 0.46 | 0.000 | 0.253 | 0.000 |

| PCE | 0.506 | 0.000 | ||||

| Model 2 | Subjective knowledge | 0.697 | 0.486 | 0.000 | −0.470 | 0.044 |

| PCE’s female respondents | −0.159 | 0.460 | ||||

| Moderating interaction of PCE on SK and PI | 1.232 | 0.001 | ||||

| Variables | Mean Score | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| SK | 34.379 | 35.82 | 0.034 |

| PCE | 35.24 | 37.16 | 0.004 |

| PI | 25.45 | 26.98 | 0.003 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, T.-C.; Situmorang, R.O.P.; Liao, M.-C.; Chang, S.-C. The Relationship of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness, Subjective Knowledge, and Purchase Intention on Carbon Label Products—A Case Study of Carbon-Labeled Packaged Tea Products in Taiwan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197892

Liang T-C, Situmorang ROP, Liao M-C, Chang S-C. The Relationship of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness, Subjective Knowledge, and Purchase Intention on Carbon Label Products—A Case Study of Carbon-Labeled Packaged Tea Products in Taiwan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):7892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197892

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Ta-Ching, Rospita Odorlina P. Situmorang, Mei-Chi Liao, and Shu-Chun Chang. 2020. "The Relationship of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness, Subjective Knowledge, and Purchase Intention on Carbon Label Products—A Case Study of Carbon-Labeled Packaged Tea Products in Taiwan" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 7892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197892

APA StyleLiang, T.-C., Situmorang, R. O. P., Liao, M.-C., & Chang, S.-C. (2020). The Relationship of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness, Subjective Knowledge, and Purchase Intention on Carbon Label Products—A Case Study of Carbon-Labeled Packaged Tea Products in Taiwan. Sustainability, 12(19), 7892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197892